Abstract

Do people feel psychological ownership toward a third place other than homes as the first place and workplaces as the second place? The present study proposes a research model integrating three characteristics of the third place including customer participation, place attachment, and psychological ownership, and tests six hypotheses derived from the research model, which is based on social identity theory and attachment theory. Communication, concentration, and self-expressiveness as characteristics of the third place have a positive influence on customer participation. Customer participation has a direct positive influence on psychological ownership as well as indirectly through place attachment.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The third place is somewhere that makes an individual feel more comfortable, pleasant, and cozy, aside from home as the first place and the workplace as the second place (Oldenburg 1989; 2001). Many researchers (Cabras and Mount 2017; Daisuke et al. 2015; Jeffres et al. 2009; Mikunda 2004) have studied the roles, usefulness, and value of the third place since Oldenburg (1989; 2001) had introduced the concept of the third place. According to Jeffres et al. (2009), about 71 percent of U.S. people have their third place. The most cited third spaces are as follows, in this order: community centers & town meetings, coffee shops, restaurants and cafés, and churches (Jeffres et al. 2009). These types of third places were grouped into four categories: eating, drinking & talking, organized activities, outside venues, and commercial venues. According to Waxman et al. (2007), the reason college students prefer the third place is that it provides major functions such as socializing, relaxation, eating and drinking, and getting away, and is a place to do homework.

Psychological ownership is a source of organizational competitiveness and refers to the psychological state that people perceive a target or object is theirs, although they are not the legal owners (Avey et al. 2009; Pierce et al. 2001, 2004). There are many studies regarding employees’ psychological ownership for organizations (Van Dyne and Pierce 2004). According to Van Dyne and Pierce (2004), psychological ownership is a psychologically experienced phenomenon in which employees develop possessive feelings for organizations or jobs. Psychological ownership is associated with three human needs: efficacy, self-identity, and belongingness (Pierce et al. 2004; Dawkins et al. 2017). Psychological ownership enhances a sense of accountability for the object (Avey et al. 2009). Thus, psychological ownership consists of the four constructs of efficacy, self-identity, belongingness, and accountability. Psychological ownership has a positive influence on individual attitudes and behavior (Van Dyne and Pierce 2004). For example, psychological ownership is positively associated with organizational citizenship behavior, which refers to volunteering for extra roles, or discretionary behaviors beyond formal roles in organizations (Van Dyne and Pierce 2004). Many studies were limited to the relationship between employees’ psychological ownership for the organization and the consequences such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment, organizational citizenship behavior, and financial performance (Dawkins et al. 2017; Van Dyne and Pierce 2004; Wagner et al. 2003).

Customers also can feel psychological ownership for the organization. According to the record of Linji who was a Chinese monk during the Tang dynasty (AD 613–907): “Just make yourself master of every situation, and wherever you stand is the true place” (Sasaki 2009, p. 186). This means that the owner spirit, or ownership, is important for people to be happy wherever they stand on the sphere. Kotler et al. (2016) argued that customers ultimately advocate products or services. Firms driving customers to advocacy from just being aware will gain sustainable competitiveness (Kotler et al. 2016). Customers can be advocators of firms or brands when they feel psychological ownership. The record of Linji and Kotler et al. (2016)’s study show that customers’ psychological ownership is important to achieving an organizational competitive advantage.

Customers are one of the primary external stakeholders of an organization, whereas employees are internal stakeholders. Customers who feel psychological ownership can make bigger contributions to organizational competitiveness. They can become advocates of the organization, just like employees. Thus, it is necessary to study determinants of psychological ownership from the perspective of customers.

Do individuals feel psychological ownership for their third place? It is not easy to find studies regarding customers’ psychological ownership of an organization. A special issue of the Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice in 2015 dealt with psychological ownership, which is a concept of value to the marketing field (Hulland et al. 2015). Articles regarding customer’s psychological ownership were published in that special issue. Organizations can have a new strategic orientation when customers feel psychological ownership for the organization or for a third place. Firms can foster the sustainable business ecosystem with customers, which is favorable to them (Joo and Marakhimov 2018). Customers play the role of partial employees (Mills and Morris 1986) and co-creators (Lee 2019; Lee and Jeong 2012). Customers become firm’s supporters and participate in corporate social responsibility activities. Then, they have psychological ownership (Joo and Marakhimov 2018). Thus, it is important to study customers’ psychological ownership of the third place as a good place provided to customers or visitors by the organizations.

The third place facilitates customer participation, and in turn, it becomes a source of place attachment. It is important to analyze the relationships among the characteristics of the third place, customer participation, place attachment, and psychological ownership because of their influence on organizational competitiveness. Thus, it is necessary to identify the antecedents of psychological ownership for the third place. The purpose of this study is to analyze the relationships between the characteristics of the third place, customer participation, place attachment, and psychological ownership. The present paper examines three characteristics of the third place: concentration, communication, and self-expressiveness. Then, significant paths linking the proposed characteristics of the third place to customers’ psychological ownership are analyzed by using a structural equation modeling approach. Most people cannot live without home even in the age of untact (Lee and Lee 2020) after the COVID-19. The present study contributes to value creation of third place through customer’s psychological ownership.

2 Theoretical background and hypotheses development.

2.1 Third place, customer participation, and place attachment

Mikunda (2004) extended the concept of the third place. According to Mikunda (2004), the third place can be a landmark, be designed for malling, feature a concept line, and draw people with a core attraction. The third place enables people to engage in social interaction and offers emotional support (Rosenbaum 2006). Rosenbaum (2006) classified the third place as a place-as-practical where an individual’s utility is satisfied, a place-as-gathering where an individual’s social needs are satisfied, and a place-as-home where an individual’s emotional needs are satisfied. The third place builds communities, facilitates social communication, and enhances quality of life in communities (Jeffres et al. 2009).

Customer participation in the service industry is associated with a customer’s ability to affect service procedures or the service itself, through the service experience (Mills and Morris 1986). The customer is an input element of the service process, and plays the partial role of employee because of the inseparable feature of the service from its operations (Mills and Morris 1986). The customer is a co-creator of value (Payne et al. 2008; Palma et al. 2019) and is also a co-producer of knowledge for organizational innovation (Blazevie and Lievens 2008). In the era of ecosystem-oriented competition, innovation through customers’ participation and collaboration is important in order to co-create value and achieve competitive advantage (Lee and Lim 2018, p. 93). Customer participation has an impact on organizational productivity and competitive advantage (Lovelock and Young 1979; Prahalad and Ramaswamy 2000).

People have a place attachment to meaningful places where affective and symbolic relations are formulated (Williams and Vaske 2003). Place attachment is defined as the emotional bond between an individual and a place (Altman and Low 1992). Place attachment generally refers to the affective and psychological bond between people and places due to their frequent visiting experiences (Hidalgo and Hernandez 2001; Woosnam et al. 2018). Thus, place attachment results from repeated visits to, and experiences with, a specific place (Gustafson 2001). According to Williams and Vaske (2003), place attachment is divided into two dimensions: place identity and place dependence. Place identity is defined as the identification of an individual with a place, which results in an emotional bond and positive feelings toward it (Kyle et al. 2004; Proshansky et al. 1983; Ramkissoon et al. 2013; Woosnam et al. 2018), whereas place dependence refers to a functional attachment representing how well a place supports individual needs (Stokols and Shumaker 1981; Woosnam et al. 2018).

Some studies regarding environmental psychology which examines transactions between individuals and their physical settings or surroundings have dealt with the relationship between a third place and place attachment (Gifford 2014). No studies were found, however, on what kinds of the characteristics of the third place lead to psychological ownership through customer participation and place attachment.

2.2 Psychological ownership

People experience psychological ownership when they perceive that they can control an object or a target, or have an influence on it, although its formal and legal ownership does not belong to them. According to Pierce et al. (2001), psychological ownership comes from three routes: controlling the target, coming to immediately know it, and investing the self in it. Avey et al. (2009) argued that the four dimensions of psychological ownership consist of self-efficacy, accountability, belongingness, and self-identity.

Psychological ownership influences organizational competitiveness (Brown 1989), organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and organizational citizenship (Avey et al. 2009; Van Dyne and Pierce 2004). A few studies have provided evidence that customers of an organization develop psychological ownership (Asatryan and Oh 2008; Joo and Marakhimov 2018). Karahanna et al. (2015)’s study regarding the relationship between psychological ownership and the use of social media suggests that psychological ownership is motivated by the need for efficacy, the need to have a place, and the need for self-identity.

2.3 Research model and hypotheses development

The third place has characteristics of comfort, openness, interactivity, playfulness, and diversity (Mikunda 2004; Oldenburg, 1989). Oldenburg (1989) suggested eight characteristics of third places: being neutral ground; being a leveler; allowing conversation; providing accessibility and accommodation; having regular patrons, a low profile, a playful mood; and being a home away from home.

The third place provides functions for studying and performing jobs as if it is a personalized and dedicated workplace. For example, libraries as a third place provide an environment for study and concentration (Waxman et al. 2007). Spaces that are physically and psychologically comfortable impact people’s learning experiences (Miller 2009). The third place becomes a private space for restoring one’s self (Sugiyama et al., 2015). Creating an environment conducive to concentration, and facilitating immersion in performing works are critical characteristics of the third place. Thus, the present paper proposes that providing a place to concentrate is a characteristic of the third place.

According to Oldenburg (1989), one of the main activities in the third place is conversation with others, in which rules of conversation tend to exist. People find and share common interests, and communicate with each other in the third place. The third place is also a space for socialization (Waxman et al. 2007). Being a place to communicate socially with people is an important feature of the third place (Sugiyama et al. 2015). The third place is a place for meetings, conversation, and communication. Thus, the present paper proposes that providing a place to communicate is a characteristic of the third place.

Places that generate feelings that are congruent with an individual’s identity will become attractive to that person. People frequently visit places that are congruent with their self-image, self-concept, and social values. When people visit a place aimed at achieving their social values, Sugiyama et al. (2015) defined such a place as a meaning-focused type of third place. One of the features of the third place is being a venue for self-expressiveness. This refers to the degree to which a place represents personal identity, a self-image, a personal lifestyle, and social values. Sirgy et al. (2016) defined self-expressiveness as the degree to which people think their activities are important components of their self-concept. The third place becomes an appropriate space for representing self-expressiveness because the third place reveals one’s own personal style, reflects a life style, and provides a sense of unity between personal identity and place identity. So, another characteristic of the third place is being a venue for self-expressiveness. The present paper suggests that characteristics of the third place include being a place for concentration, communication, and self-expressiveness.

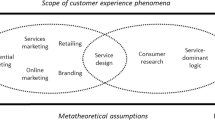

Characteristics of the third place are associated with customer participation. Customer participation in the third place causes feelings of attachment and psychological ownership. Customers who proactively communicate and cooperate by providing feedback and suggestions feel a stronger psychological ownership resulting from place attachment and compassion toward the third place. The more actively customers participate, the more likely they are to feel psychological ownership toward the third place. An empirical study by Joo and Marakhimov (2018) regarding psychological ownership toward Facebook shows that customer participation positively influences psychological ownership. Place attachment is positively associated with psychological ownership. Figure 1 shows the research model integrating the characteristics of the third place, customer participation, place attachment, and psychological ownership.

According to oriental philosophy (for example, the four sprouts of human nature), compassion emerges from the feeling of commiseration or concern for others, and from empathy. Empathy is described as a concept “that is more other-focused than self-focused, including feelings of sympathy, compassion, tenderness, and the like” (Goetz et al. 2010, p. 351). Goetz et al. (2010) argues that “empathy clearly is involved in the elicitation and experience of compassion, but compassion does not reduce to an empathic state of mirrored distress, fear, or sadness” (Goetz et al. 2010, p. 365). On the other hand, according to Stevens and Woodruff (2018), compassion includes three domains: affective empathy, cognitive understanding of how others feel difficulties, and a desire to help them. The third concept of compassion differentiates it from empathy (Stevens and Woodruff 2018, p. 7). People who feel a psychologically higher ownership toward a target generate greater compassion. Thus, compassion is a component of psychological ownership.

Customers who participate proactively in a business activity or the third party empathize with a feeling of commiseration and facilitate the emergence of compassion so that they feel psychological ownership toward the third place or the business. In the present paper, psychological ownership consists of a sense of mine which is associated with a general conceptual definition (Avey et al. 2009; Pierce et al. 2001) described in the introductory section, and a sense of compassion.

2.3.1 Characteristics of the third place and customer participation

Claycomb et al. (2001) classified the levels of customer participation as low, moderate, or high. At a low level, customer participation refers to service from the third place by simply visiting the third place. At a moderate level of customer participation, customers provide feedback and suggestions to the third place. Customer participation at a high level contributes to the co-creation of value by assisting the third place or helping its visitors. Customer participation at a low level is passive, whereas customers at moderate and high levels actively participate. The level of customer participation exists along a continuum ranging from passive at one end, where customers are simple observers or simply visiting third places for transactions or meeting, to active at the other, where they affect the business performance as co-creators of the experience (Pine and Gilmore 1998). In the present study, the active customer participation is classified into feedback on and cooperation with the third place as described in Table 1.

Bitner (1992) proposed servicescapes as a conceptual framework that describes the impact of physical surroundings on customers’ behavior in service organizations. Servicescapes include ambient conditions (such as temperature, music, and odor), space and function (such as layouts and furnishings), and signs and artifacts (such as signage and décor) (Bitner, 1992). According to Bitner (1992), servicescapes are important for eliciting participation in the third place. Servicescapes influence customers’ behavior in which active customer participation is important (Bitner 1992; Clarke and Schmidt 1995). Social, emotional, and experiential characteristics of the third place are also significant for encouraging people’s participation.

According to Oldenburg (1989), third places encourage civic engagement so that they contribute to the well-being of individuals (Williams and Hipp 2019). From among the eight characteristics of the third place, Oldenburg (1989) suggested that conversation and communication encourage people’s participation. Thus, the communication characteristic of the third place is associated with customer participation.

Recently, the third place has provided an environment conducive to work or study, rather than home, and it improves one’s concentration level when studying or working there. Many coworkers who simply work alone, or together if necessary, share a co-working space without much interaction (Brown 2017). Some co-working spaces provide a flexible and right mix of autonomy and interaction for young entrepreneurs and freelance workers or digital nomads (Brown 2017). The third place becomes an alternative to a co-working space because it allows visitors to not only do their autonomous work alone but also to collaborate through interactions. The concentration characteristic of the third place leads to customer participation.

The symbolic self-completion theory suggests that people who have an incomplete self-definition tend to complete their identity by acquiring and demonstrating symbols related to themselves (Wicklund and Gollwitzer 1981). Symbolic expressions of the self refer to core values or individuality (Dawkins et al. 2017). Consumers prefer brands offering a closer fit between personal identity and brand identity known as self-congruence. Space marketing or experiential marketing (Schmitt 1999) stresses the space design helping to satisfy a customer’s desire for self-expressiveness. Experiential marketing aims to create holistic experiences: to sense (sensory experience), to feel (affective experience), to think (creative cognitive experience), to act (physical experience, behaviors, and lifestyles), and to relate (social identity experience). Social identity experience covering the four other experiences is closely related to self-expressiveness, because it is a key component to fostering social identity. People think that the third place represents a symbolic expression of the self. For example, Howard Schultz (chairman and former CEO of Starbucks) argued that Starbucks is a cozy home away from home as a third place (Rice 2009) and sells not coffee but experiences to customers. The more that customers perceive the characteristics of self-expressiveness in the third place as positive, the more they are likely to proactively participate in the third place.

The characteristics of concentration, communication, and self-expressiveness lead to customers’ active participation in the third place. The following three hypotheses regarding relationships between the characteristics of the third place and customer participation are therefore proposed.

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

The concentration characteristic of the third place has a positive influence on customer participation.

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

The communication characteristic of the third place has a positive influence on customer participation.

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

The self-expressiveness characteristic of the third place has a positive influence on customer participation.

2.3.2 Customer participation, place attachment, and psychological ownership

Active participation in the third place including customers’ suggestions and feedback as well as cooperating efforts with the third place is positively associated with attachment to the place. According to a study by Xu and Zhang (2016) regarding antecedents and outcomes of place attachment, customers’ involvement has a positive influence on place attachment. They also argued that a high level of tourist involvement facilitates the formation of attachment to tour destinations. Studies have identified how tourists’ continuous participation in a tour destination influences their attachment to that place (Hou et al. 2005; Lee and Shen 2013). According to Lee and Shen (2013), customers’ participation in leisure activities is positively associated with their attachment to a place. According to Luo et al. (2016), activity involvement in the third place positively influences place attachment. Subsequently, place attachment has a positive effect on a visitor’s loyalty toward the third place. Place attachment is associated with an individuals’ participation, because place attachment stems from the experiences therein. Frequent visitation increases place dependence; therefore, repeated visitations due to place dependence improve place identity (Clarke et al. 2018; Vaske and Kobrin 2001). There is a positive relationship between customer participation and place attachment. Thus, the following hypothesis regarding the relationship between customers’ participation and their attachment to the third place is proposed.

Hypothesis 4 (H4):

Customer participation has a positive influence on place attachment.

Some studies have identified a positive relationship between customers’ participation in offline and online business activities and their psychological ownership. Asatryan and Oh (2008) analyzed antecedents and consequences of psychological ownership by using data collected from customers of university restaurants. Their study found that customer participation and perceived control, and their sense of belonging, are determinants of psychological ownership (Asatryan and Oh 2008). Joo and Marakhimov (2018) proposed a research model integrating the organizational socialization of customers, customer participation, and psychological ownership, and suggested a positive relation between customer participation and psychological ownership of Facebook. Their empirical research, using data from 397 Facebook users, showed that psychological ownership plays a mediating role between customers’ participation at the individual firm level and their participation in the business ecosystem via word-of-mouth and boycott intention as citizenship behaviors. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 5 (H5):

Customer participation has a positive influence on psychological ownership.

According to Shu and Peck (2011), feelings of attachment to a place are connected to psychological ownership. Some studies have suggested that psychological ownership is positively associated with aspects of attachment such as giving a higher valuation to customers (Baxter et al. 2015; Reb and Connolly 2007). Place attachment provides various psychological benefits such as emotional and cognitive restoration, escape from daily stressors, and social capital (Billig 2006; Hartig et al. 2001; Scannell and Gifford 2017). Belongingness as a psychological benefit comes from place attachment (Billig 2006; Scannell and Gifford 2017). The more attachment that customers have to a third place, the more they feel a sense of ownership. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 6 (H6):

Place attachment has a positive influence on psychological ownership.

3 Methodology: measurement and sampling design

Figure 2 shows the procedure for measurement and sampling. Questionnaire items for each construct shown in Table 1 were developed and adapted from extant studies, and were then reviewed by three experts in the areas of tourism, marketing, and human resources who work at Dongguk University in South Korea. Pretesting of the questionnaire to determine if it worked correctly was conducted by using Google Drive and the KakaoTalk mobile messenger service. Feedback through KakaoTalk from respondents was helpful in revising the questionnaire items. Measurement scales for a total of eight constructs with 36 question items were completed for the final survey, shown in Table 2. Seven constructs were measured using reflective scales, while cooperation was measured using a formative construct. All question items in Table 2 were measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The questionnaire was written in Korean and translated into English after conducting the survey in order to write the present paper.

Two assistants for this research visited 16 locations, including coffee shops, restaurants, bars, and libraries, located in three metropolitan areas (Seoul, Pusan, and Gwangju) and two provinces (Gyeonggi and Gyeongbuk) to collect data through a face-to-face survey. The survey was conducted for about four months from October 18, 2017, to February 20, 2018. A valid sample of 562 respondents was collected and used for analysis.

4 Analysis

SPSS Statistics (version 23) and Smart PLS (version 3.2.7, Ringle et al. 2015) were employed to analyze the data. Table 3 shows the demographic characteristics of respondents. Almost 53% of the 562 respondents were female, and more than 69% were aged 20–39. 52% had used their third place for more than three years (Question: how many years have you been visiting the third place?). Nearly 37% cited a coffee shop as their third place, and just over 28% identified a bar as their third place (Question: where is your third place? 1. Coffee shops; 2. Libraries; 3. Cafes; 4. Restaurants; 5. Other [please write down your third place]).

4.1 Common method bias

Common method bias (CMB) is an error caused by the measurement method used in a structural equation modeling study in a data gathering process (Kock 2015). To avoid CMB, the total variance of the unrotated first factor should be less than 50%, using a Harman single factor test that considers all items in exploratory factor analysis (Podsakoff et al. 2003). The first factor in this study explains 34.19% of the total variance. Thus, the possibility of CMB is low. Another approach to test CMB is to use a variance inflation factor (VIF). A structural equation model contaminated with a common method bias includes a latent variable with a VIF value greater than 3.3 (Kock 2015). VIFs for all latent variables in this study ranged from 1.000 to 1.453. Thus, the research model has no CMB.

4.2 Reliability and validity

Table 4 shows the path loadings connecting each construct to the indicator variables, VIF, Cronbach’s alpha, CR (Composite Reliability), AVE (Average Variance Extracted), and the type of construct. VIF is used to check for the problem of multicollinearity. A VIF threshold may exceed 5 in variance-based SEM including PLS (Partial Least Square) (Garson, 2016; Kock and Lynn 2012). However, a VIF threshold of 3.3 is recommended for each of the formative indicators of an underlying construct (Kock and Lynn 2012). Inner VIF values for all latent variables were less than 1.50, and outer VIF values for the formative latent variable of cooperation were less than 2.00, as shown in Table 4. Thus, there are no multicollinearity problems. The indicator reliability of the reflective measurement models was acceptable because the outer model loadings for all reflective constructs were greater than 0.7 (Hair et al. 2014, p. 103; Henseler et al. 2012). Multicollinearity among the indicators for formative factor cooperation is not problematic because the VIFs were less than 4.0 (Hair et al. 2014). Every Cronbach’s alpha of the reflective constructs exceeded the 0.7 threshold for internal consistency (Nunnally and Bernstein 1994). CR for all reflective constructs also exceeded the cutoff value of 0.7 (Henseler et al. 2012). Thus, reliability and convergent validity of the reflective model were satisfactory (Fornell and Larcker 1981). According to Hair et al. (2014), there is no clear criterion on whether to measure a construct reflectively or formatively. Reflective indicators are caused by a latent variable, whereas formative indicators cause a latent variable. Formative indicators are measures that form or contribute to an underlying construct. Chin (1998a, b) suggested this question: “Is it necessarily true that if one of the items (assuming all are coded in the same direction) were to suddenly change in a particular direction, the others will change in a similar manner?” If the answer is no, the construct is formative. A cooperation effort that is representative of customer participation in the third place was composed of three measurements as shown in Table 2. All indicator weights for the cooperation construct as a formative factor were significant as shown in Table 4.

Table 5 shows inter-construct correlations and the square root of the AVE for each construct. Values in the diagonal cells indicate the square root of the AVE. The square root of the AVE for each reflective construct is higher than its correlations with other constructs. According to the Fornell and Larcker criterion, the discriminant validity is satisfactory (Fornell and Larcker 1981).

The HTMT (Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio) was suggested as a criterion of discriminant validity by Henseler et al. (2015). Discriminant validity is satisfactory for a given pair of reflective constructs, if the HTMT value is below 0.90 (Garson 2016). Gold et al. (2001) and Teo et al. (2008) also recommended the 0.90 threshold, although Kline (2011) used a more stringent cutoff of 0.85. All values in Table 6 are less than 0.85. Thus, discriminant validity was satisfied.

In general, when using PLS, SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual) is used as the measure for approximate fit of the structural model (Garson 2016). The structural model has good fit because the SRMR value of 0.084 is close to the cutoff of 0.08 (Hu and Bentler 1999).

Although SRMR indicates an acceptable fit when it produces a value smaller than 0.10, it can be interpreted as an indicator of good fit when it produces a value lower than 0.05 (Kline 2011; Hu and Bentler 1999). One of the reasons for preferring the SRMR index in studies is its relative independence from sample size.

4.3 Hypothesis test

Figure 3 includes the two second-order constructs of customer participation and psychological ownership. Customer participation as a second-order construct contains two indicators of its first-order subconstructs of customer feedback and cooperation. Psychological ownership as another second-order construct contains two indicators of its first-order latent variables including sense of mine and sense of compassion. All path coefficients between first-order latent variables and second-order constructs that indicate the loadings of first-order constructs on the second-order constructs exceeded 0.7, as shown in Fig. 3.

Path analysis using SmartPLS (Ringle et al. 2015) was used to test the six hypotheses. A bootstrap with 1,000 subsamples and a one-tailed test were performed. As shown in Table 7, all hypotheses were supported. Hypothesis, H1 was supported at the significance level of 0.01, H2 was supported at the significance level of 0.05, and H3 to H6 were supported at the significance level of 0.01.

R-square, known as the coefficient of determination, is measured by the variance explained through the model (Garson 2016). Chin (1998a, b) classified the level of explanatory power as substantial at a threshold of 0.67, for a moderate level, a cutoff of 0.33, and for a weak level, a cutoff of 0.19 (Chin 1998a, b; Garson 2016). Table 8 shows the R-square with the t-value and p-value. All R-squares exceeded the 0.19 cutoff value. In particular, the two latent variables of customer participation and place attachment explain 66% of the variance in psychological ownership as an endogenous variable.

Customer participation and place attachment are mediating variables between characteristic variables of the third place (CON, COM, and SEL) on the one hand and psychological ownership on the other, as shown in Table 9. According to Hair et al. (2017), a mediating variable is complementary partial mediation if both the indirect effect and the direct effect are significant and the product of the indirect effect and direct effect is positive. The strength of mediation is measured with the variance accounted for (VAF) method (Hair et al. 2014). Partial mediation is demonstrated when the VAF exceeds 0.20 and is less than 0.80. Place attachment plays the role of complementary partial mediation between customer participation and psychological ownership. P-value of Sobel test for the place attachment as a mediator is less than 0.001.

5 Discussion

What are the determinants of psychological ownership toward the third place? The antecedents of psychological ownership include customer participation and place attachment. Proactive customer participation (including feedback and cooperation) directly impacts psychological ownership, and has an indirect effect on it through place attachment as a mediating variable. According to Fuchs et al. (2010), customers who participate in T-shirt design are more likely to experience psychological ownership for the product, even without buying it. The result of testing the hypothesis regarding customer participation and psychological ownership (H5) is supported by previous studies (Asatryan and Oh 2008; Joo 2018; Joo and Marakhimov 2018). Customer participation plays a significant role as a mediating variable between the characteristics of the third place and psychological ownership. Extant studies regarding place attachment argue that repeated visitation to a place, as well as its physical and symbolic features, enhances a sense of unity between the place and personal identity (Anton and Lawrence 2016; Clarke et al. 2018; Vaske and Kobrin 2001). The result of testing the fourth hypothesis (H4), that the more customers participate in the third place the greater the place attachment, is consistent with place attachment theory.

The result of the present research indicates that three characteristics of the third place (concentration, communication, and self-expressiveness) facilitate proactive customer participation. Concentration, communication, and self-expressiveness trigger psychological ownership through customer participation and place attachment. To elicit proactive customer participation, the third place needs to play the roles of conversation and communication for customers. According to Oldenburg (1989), the main activity of the third place is conversation. Jeffres et al. (2013) argued that the climate for communication in the third place is important to customers. Servicescape theory that a facility’s exteriors & interiors and ambient conditions as a physical environment in the third place affect customer’s service experience, is consistent with the finding that the communication characteristic of the third place has a positive influence on customer participation. The third place must also be a free and comfortable space allowing customers to concentrate on their work without being interrupted by others. Furthermore, customers have to experience self-expressiveness in the third place. The experience of self-expressiveness is optimized as customers come to feel that the third place matches their personal style, reflects their life style, and expresses their self-concept.

According to Jensen and Aaltonen (2013), offline retail stores have to be theaters in order to exist in the era of the e-commerce revolution, because online stores beat out offline stores in terms of transaction costs. The concept of the theater is associated with the optimization of customers’ emotional responses or experiences. It is necessary for offline stores to inspire customers to pursue their dreams, because the stores have to perform the role of culture space beyond a simple transaction place. The characteristics of the third place such as concentration and self-expressiveness contribute to optimizing customer experiences through their proactive participation. According to social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner 1986; Turner and Oakes 1986), people prefer places or objects congruent with their own self-concept or self-image (Pagani et al. 2011). The study by Pagani et al. (2011) regarding the influence of identity on active participation in a social networking site (SNS) argued that both personal identity and social identity are positively associated with active use of an SNS. Thus, the analysis result showing that a place enabling self-expressiveness drives customers’ proactive participation in the third place is supported by social identity theory.

The communication characteristic of the third place has an influence on proactive customer participation at the significance level of 0.05. Concentration and self-expressiveness affect proactive customer participation in the third place at significant levels of 0.01 and 0.001, respectively. Why does the effect on the proactive customer participation that impacts psychological ownership vary depending on the characteristics of the third place? A feature of a social place for communication is that it not only encourages customers to make repeated visits, but also induces proactive customer participation. According to Sugiyama et al. (2015), there are communication places and private places, where the latter refers to a personalized type of third place. Private places indicate that customers are spending time to restore themselves. The private place is closely related to the concentration characteristic beyond that of communicating socially with other people.

According to Rosenbaum (2006), the third place satisfies customers with physical, social, and emotional needs. The characteristics of concentration and self-expressiveness are closely related to emotional needs, while communication satisfies customers with social needs. Customers feel a sense of ownership in a third place that satisfies their emotional needs.

Thus, customers participate proactively in the third place and have a sense of psychological ownership when their experience enhances concentration and self-expressiveness. A study by Griffiths and Gilly (2012) on customer territorial behaviors using the third place as an extension of the workplace or home supports the result of the present study. According to Griffiths and Gilly (2012), territorial behaviors are associated with attempts to create a space to match an individual’s preferences, and customers who embrace the third place as primary territory have a sense of ownership and territorial control.

It is necessary to pay attention to total effects through mediation paths linking the three characteristics of the third place to psychological ownership as shown in Table 9. The total effects of concentration, communication, and self-expressiveness were 0.079, 0.055, and 0.232, respectively. The characteristic of fostering self-expressiveness in the third place strongly leads to psychological ownership through customer participation. Studies based on identity theory showed evidence that consumers prefer products or brands that match their own self-concepts (Ilaw 2014; Sirgy et al. 2016). Furthermore, self-image congruity has a positive influence on consumers’ brand preferences and purchases, which are generated as forms of self-expression (Ilaw 2014; Sirgy et al. 2016). Thus, the finding of the present study is supported by identity theory.

The present study proposed a new model integrating the relationships among characteristics of the third place, customer participation, place attachment, and psychological ownership. Finding a missing link connecting the characteristics of the third place and customer psychological ownership contributes to extending studies regarding the third place and psychological ownership. The present study sheds light on interdisciplinary research regarding the third place, on customer participation, and on psychological ownership. The third place has been predominantly researched in the area of environmental psychology, customer participation was researched in marketing, place attachment was examined under tourism and environmental psychology, and psychological ownership was studied in human resource management area.

This study has some implications for practitioners. The results of the present study stress the significance of customers’ psychological ownership for sustainable growth of the third place. First, the third place needs to allow customers to proactively participate in working processes beyond simply visiting or staying in the location. Second, proactive participation of customers has a significant effect on psychological ownership through an emotional or affective bond between customers and their third place. Thus, managers of a third place need to understand the characteristics of the third place that become antecedents of proactive customer participation in order to develop place attachment in their customers. Third, managers of a third place need to provide a space enabling customers to concentrate on their work activities without being interrupted by others. By the way, a space for conversation is not always compatible with that of concentration. For example, a space allowing enough conversation can interrupt other customers’ concentration. Managers need to make a strategic plan for breaking the tension between conversation and concentration. Sometimes, this can depend on culture and the type of third place. Managers of coffee shops in collectivist cultures have greater difficulty finding solutions to this tension, compared to individualist cultures. Libraries and PC-bangs are more suitable for concentration than restaurants. Fourth, it is important for the third place to match an individual’s identity and life style, because self-expressiveness has a significant influence on customer participation, which in turn, is a determinant of psychological ownership. The results of the study contribute to understanding the emerging function of the third place for our changing life styles.

6 Concluding remarks

In sum, place attachment and customer participation in providing feedback and cooperating with the third place are significant determinants of customers’ psychological ownership toward the third place. As the third place facilitates self-expressiveness and concentration as well as functionalities such as transactions, meetings, and communication, customers more proactively participate in the third place. The result of the present study regarding customer’s psychological ownership underlines the importance allowing self-expressiveness and concentration in the third place beyond the communication that extant studies (Oldenburg 1989; Jeffres et al. 2009) had already emphasized as significant.

Place characteristics that enable customers to express themselves, and that help them concentrate on their work have a significant influence on active participation in the third place. Therefore, self-expressiveness and concentration are important sources of psychological ownership toward the third place. A third place where customers can concentrate on their work, or where they think the place matches their life style and identity, leads to proactive participation, which is an antecedent to psychological ownership. As managers of the third place come to understand that customers prefer to have a place representing their personal identities, revealing who they really are, and providing characteristics much like a private space where it is appropriate to perform their work, the third place can be a source of competitive advantage for organizations by making customers feel psychological ownership toward it.

Psychological ownership toward the third place leads to sustainable business and customer loyalty. Extant studies argued that psychological ownership is closely related to firm competitiveness (Dawkins et al. 2017; Wagner et al. 2003). Effective design of and operations in the third place enabling customer concentration and self-expressiveness have become a new managerial challenge for third places like libraries, coffee shops, and restaurants. The third place will face crisis because untact culture has been expanding since the COVID-19 pandemic and e-commerce had already exceeded offline transactions (Jensen and Aaltonen 2013). However, the results of the research regarding third place characteristics leading to customer’s psychological ownership provide insights on how the third place can be differentiated from online services.

The present study has a limitation in the sampling and generalization of the research findings. A motive for a respondent to choose the third place can be different from others. For further study, a type of the third place can be introduced to the research model as a moderator.

References

Altman I, Low S (1992) Place attachment. Plenum Press, New York

Anton CE, Lawrence C (2016) The relationship between place attachment: the theory of planned behaviour and residents' response to place change. J Environ Psychol 47:145–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.05.010

Asatryan VS, Oh H (2008) Psychological ownership theory: an exploratory application in the restaurant industry. J Hos Tour Res 32(3):363–386

Avey JB, Avolio BJ, Crossley CD, Luthans F (2009) Psychological ownership: theoretical extensions, measurement and relation to work outcomes. J Org Behav 30(2):173–191

Baxter WL, Aurisicchio M, Childs PRN (2015) A psychological ownership approach to designing object attachment. J Eng Des 26(4–6):140–156

Billig M (2006) Is my home my castle? Place attachment, risk perception, and religious faith. Environ Behav 38:248–265

Bitner M (1992) Servicescapes: the impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. J Market 56(2):57–71

Bitner M, Faranda WT, Hubbert AR, Zeithaml VA (1997) Customer contributions and roles in service delivery. Int J Ser Ind Man 8(3):193–205

Blazevie V, Lievens A (2008) Managing innovation through customer co-produced knowledge in electronic services: an exploration study. J Acad Market Sci 36:138–151

Brown J (2017) Curating the “third place”? coworking and the mediation of creativity. Geoforum 82:112–126

Brown TL (1989) What will it take to win? Indus Week, June 19, 15.

Cabras I, Mount MP (2017) How third places foster and shape community cohesion, economic development and social capital: the case of pubs in rural. J Rural St 55:71–82

Chen C (2017) Influence of celebrity involvement on place attachment: role of destination image in film tourism. Asia Pacific J Tour Res 23(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2017.1394888

Chin WW (1998a) Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Quar 22(1):vi–xvi

Chin WW (1998b) The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling. In: Macoulides GA (ed) Modern methods for business research. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ, pp 295–336

Clarke D, Murphy C, Lorenzoni I (2018) Place attachment, disruption and transformative adaptation. J Environ Psychol 55:81–89

Clarke I, Schmidt RA (1995) Beyond the servicescape—the experience of place. J Retail Consum Ser 2(3):149–162

Claycomb C, Lengnick-Hall CA, Inks LW (2001) The customer as a productive resource: a pilot study and strategic implications. J Bus Strateg 18(1):47–69

Daisuke S, Kunio S, Michitaka K (2015) Elements to organize the third place that promotes sustainable relationship in service businesses. Tech Soc 43:115–121

Dawkins S, Tian AW, Newman A, Martin A (2017) Psychological ownership: a review and research agenda. J Org Behav 38(2):163–183

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18:39–50

Fuchs C, Prandelli E, Schreier M (2010) The psychological effects of empowerment strategies on consumers’ product demand. J Mark 74(1):65–79

Garson GD (2016) Partial least squares: regression & structural equation models. https://www.smartpls.com/resources/ebook_on_pls-sem.pdf. Accessed 20 November 2019

Gifford R (2014) Environmental psychology matters. Ann Rev Psychol 65:541–579

Goetz JL, Keltner D, Simon-Thomas E (2010) Compassion: an evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychol Bull 136(3):351–374

Gold AH, Malhotra A, Segars AH (2001) Knowledge management: an organizational capabilities perspective. J Manag Inf Syst 18(1):185–214

Griffiths MA, Gilly MC (2012) Dibs! customer territorial behaviors. J Serv Res 15(2):131–149

Gustafson P (2001) Meanings of place: everyday experience and theoretical conceptualizations. J Environ Psychol 21(1):5–6

Hair JF Jr, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2014) A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

Hair JF Jr, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2017) A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

Hartig T, Kaiser FG, Bowler PA (2001) Psychological restoration in nature as a positive motivation for ecological behavior. Environ Behav 33:590–607

Hau LN, Thuy PN (2016) Customer participation to co-create value in human transformative services: a study of higher education and health care services. Serv Bus 10(3):603–628

Henseler JR, Christian M, Sarstedt M (2012) Using partial least squares path modeling in international advertising research: basic concepts and recent issues. In: Okzaki S (ed) Handbook of partial least squares: concepts, methods and applications in marketing and related fields. Springer, Berlin, pp 252–276

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt MA (2015) New criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci 43(1):115–135

Hidalgo MC, Hernandez B (2001) Place attachment: conceptual and empirical questions. J Environ Psychol 21(3):273–281

Hou JS, Lin CH, Morais DB (2005) Antecedents of attachment to a cultural tourism destination: the case of Hakka and non-Hakka Taiwanese visitors to Pei-Pu. Taiwan J Travel Res 44(2):221–233

Hu L, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equat Mod 6(1):1–55

Huhh J (2008) Culture and business of PC Bangs in Korea. Gam Cult 3(1):26–37

Hulland J, Thompson A, Smith M (2015) Exploring uncharted waters: use of psychological ownership theory in marketing. J Market Theor Pract 23(2):140–147

Ilaw MA (2014) Who you are affects what you buy: the influence of consumer identity on brand preference. Elon J Undergr Res Comm 5(2):5–16

Jeffres LW, Bracken CC, Jian G, Casey MF (2009) The impact of third places on community quality of life. Appl Res Qual Life 4:333–345

Jeffres LW, Neuendorf K, Jian G, Cooper K (2013) Auditing communication systems to help urban policy makers. In Gallagher V, Drucker S, Matsaganis, M (Eds), Urban communication reader III: communicative cities and urban communication in the 21st century. New York: Peter Lang, pp 99–136. https://academic.csuohio.edu/kneuendorf/c63113/Jeffres/JeffresetalURBAN13.pdf

Jensen R, Aaltonen M (2013) The renaissance society: how the shift from dream society to the age of individual control will change the way you do business. McGraw-Hill, New York

Joo J, Marakhimov A (2018) Antecedents of customer participation in business ecosystems: evidence of customers’ psychological ownership in Facebook. Serv Bus 12(1):1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-017-0335-8

Joo J (2018) Mediating role of psychological ownership between customer participation and loyalty in the third place. J Dist Sci 16(3):5–12

Karahanna E, Xu SX, Zhang N (2015) Psychological ownership motivation and use of social media. J Mar Theor Pract 23(2):185–207

Kim S, Choi H (2003) PC-Bang (Room) culture: z study of Korean college students' private and public use of computers and the Internet. Trends Commun 11(1):63–79. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15427439TC1101_05

Kline RB (2011) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 3rd edn. The Guilford Press, New York

Kock N (2015) Common method bias in PLS-SEM: a full collinearity assessment approach. Int J e-Collab 11(4):1–10

Kock N, Lynn GS (2012) Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: an illustration and recommendations. J Assoc Info Syst 13(7):546–580

Kotler P, Kartajaya H, Setiawan I (2016) Marketing 4.0: moving from traditional to digital. Wiley, New York

Kyle G, Graefe A, Manning R, Bacon J (2004) Effects of place attachment on users' perceptions of social and environmental conditions in a natural setting. J Environ Psychol 24(2):213–225

Lee D (2019) Effects of key value co-creation elements in the healthcare system: focusing on technology applications. Serv Bus 13(2):389–417

Lee SM, Lee D (2020) “Untact”: a new customer service strategy in the digital age. Serv Bus 14:1–22

Lee SM, Lim S (2018) Living innovation: from value creation to the greater good. Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley

Lee Y, Chen A (2011) Usability design and psychological ownership of a virtual world. J Manag Inf Syst 28(3):269–308

Lee SA, Jeong M (2012) Effects of e-servicescape on consumers’ flow experiences. J Hosp Tour Tech 3(1):47–59

Lee TH, Shen YL (2013) The influence of leisure involvement and place attachment on destination loyalty: evidence from recreationists walking their dogs in urban parks. J Environ Psychol 33:76–85

Lovelock CH, Young RF (1979) Look to consumers to increase productivity. Harv Bus Rev 57:168–178

Luo Q, Wang J, Yun W (2016) From lost space to third place: the visitor's perspective. Tour Manag 57:106–117

Mikunda C (2004) Brand lands, hot spots & cool spaces: welcome to the third place and the total marketing experience. Kogan Page Publishing, London

Miller H (2009) Adaptable spaces and their impact on learning research summary. Herman Miller Research Summary, Zeeland, pp 1–9

Mills PK, Morris J (1986) Clients as ‘partial’ employees of service organizations: role development in client participation. Acad Manag Rev 11(4):726–735

Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH (1994) Psychometric theory, 3rd edn. McGraw-Hill, New York

Oldenburg R (1989) The great good place: cafes, coffee shops, community centers, beauty parlors, general stores, bars, hangouts, and how they get you through the day. Paragon House, New York

Oldenburg R (2001) Celebrating the third place: inspiring stories about the “great good places” at the heart of our communities. Da Capo Press, New York

Pagani M, Hofacker CF, Goldsmith RE (2011) The influence of personality on active and passive use of social networking sites. Psychol Mark 28(5):441–456

Palma FC, Trimi S, Hong S (2019) Motivation triggers for customer participation in value co-creation. Serv Bus 13(3):557–580

Payne AF, Storbacka K, Frow P (2008) Managing the co-creation of value. J Acad Mark Sci 36(1):83–96

Pierce JL, Kostova T, Dirks KT (2001) Toward a theory of psychological ownership in organizations. Acad Man Rev 26(2):298–310

Pierce JL, O'driscoll MP, Coghlan AM (2004) Work environment structure and psychological ownership: the mediating effects of control. J Soc Psychol 144(5):507–534

Pine JB II, Gilmore JH (1998) Welcome to the experience economy. Harv Busi Rev 74(4):97–105

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88(5):879–903

Prahalad CK, Ramaswamy V (2000) Co-opting customer competence. Harv Bus Rev 78(1):79–87

Prayag G, Ryan C (2012) Antecedents of tourists' loyalty to Mauritius: the role and influence of destination image, place attachment, personal involvement, and satisfaction. J Trav Res 51(3):342–356

Proshansky HM, Fabian AK, Kaminoff R (1983) Place-identity: physical world socialization of the self. J Environ Psychol 3(1):57–83

Ramkissoon H, Smith LDG, Weiler B (2013) Testing the dimensionality of place attachment and its relationships with place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviours: a structural equation modelling approach. Tour Manag 36:552–566

Reb J, Connolly T (2007) Possession, feelings of ownership, and the endowment effect. Judgm Decis Mak 2:107–114

Revilla-Camacho MA, Vega-Vázquez M, Cossio-Silva FJ (2015) Customer participation and citizenship behaviour effects on turnover intention. J Bus Res 68(7):1–5

Rice D (2009) Starbucks and the battle for third place. Gatton Student Research Publication 1(1): 30–41, Gatton College of Business & Economics, University of Kentucky. https://www.scribd.com/document/222126996/Starbucks-and-the-Battle-for-Third-Place

Ringle, CM, Wende, S, Becker, JM (2015) SmartPLS 3. Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH. https://www.smartpls.com.

Rosenbaum MS (2006) Exploring the social supportive role of third places in consumers’ lives. J Serv Res 9(1):59–72

Sasaki RF (2009) The record of Linji. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu

Scannell L, Gifford R (2017) The experienced psychological benefits of place attachment. J Environ Psychol 51:256–269

Schmitt B (1999) Experiential marketing. J Market Manag 15(1–3):53–67

Shu SB, Peck J (2011) Psychological ownership and affective reaction: emotional attachment process variables and the endowment effect. J Consum Psychol 21(4):439–452

Sirgy MJ, Lee D, Yu GB, Gurel-Atay E, Tidwell J, Ekici A (2016) Self-expressiveness in shopping. J Retail Consum Serv 30:292–299

Stevens L, Woodruff CC (2018) What is this feeling that I have for myself and for others? Contemporary perspectives on empathy, compassion, and self-compassion, and their Absence 1–21. In: Stevens L, Woodruff CC (eds) The neuroscience of empathy, compassion, and self-compassion. Academic Press, Cambridge, pp 1–21

Stokols D, Shumaker SA (1981) People and places: a transactional view of settings. In: Harvey J (ed) Cognition, social behavior, and the environment. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp 441–488

Sugiyama D, Shirahada K, Kosaka M (2015) Elements to organize the third place that promotes sustainable relationships in service businesses. Tech Soc 43:115–121

Tajfel H, Turner JC (1986) The social identity theory of intergroup behaviour. In: Worchel S, Austin WG (eds) Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Nelson-Hall, Chicago, IL, pp 7–24

Teo TSH, Srivastava SC, Jiang L (2008) Trust and electronic government success: an empirical study. J Manag Inf Syst 25(3):99–132

Turner JC, Oakes PJ (1986) The significance of the social identity concept for social psychology with reference to individualism, interactionism and social influence. Brit J Soc Psychol 25(3):237–252

Van Dyne L, Pierce JL (2004) Psychological ownership and feelings of possession: three field studies predicting employee attitudes and organizational citizenship behavior. J Org Behav 25(4):439–459

Vaske JJ, Kobrin KC (2001) Place attachment and environmentally responsible behavior. J Environ Educ 32(4):16

Wagner SH, Parker CP, Christiansen ND (2003) Employees that think and act like owners: effects of ownership beliefs and behaviors on organizational effectiveness. Pers Psychol 56(4):847–871

Waxman L, Clemons S, Banning J, McKelfresh D (2007) The library as place providing students with opportunities for socialization, relaxation, and restoration. New Library World 108(9/10):424–434

Wicklund RA, Gollwitzer PM (1981) Symbolic self-completion, attempted influence, and self-deprecation. Bas Appl Soc Psychol 2(2):89–114

Williams DR, Vaske JJ (2003) The measurement of place attachment: validity and generalizability of a psychometric approach. For Sci 49(6):830–840

Williams SA, Hipp JR (2019) How great and how good?: third places, neighbor interaction, and cohesion in the neighborhood context. Soc Scie Res 77:68–78

Woosnam KM, Aleshinloye KD, Ribeiro MA, Stylidis D, Jiang J, Erul E (2018) Social determinants of place attachment at a World Heritage Site. Tour Manag 67:139–146

Wu CH (2011) A re-examination of the antecedents and impact of customer participation in service. Serv Ind J 31(6):863–876

Xu Z, Zhang J (2016) Antecedents and consequences of place attachment: a comparison of Chinese and Western urban tourists in Hangzhou, China. J Dest Mark Manag 5(2):86–96

Zhao Q, Chen CD, Wang JL (2016) The effects of psychological ownership and TAM on social media loyalty: an integrated model. Tel Informatics 33(4):959–972

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2017S1A5A2A01023642), and this work was supported by the Dongguk University Research Fund of 2019.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Joo, J. Customers’ psychological ownership toward the third place. Serv Bus 14, 333–360 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-020-00418-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-020-00418-5