Abstract

Background

Patient-physician sex discordance (when patient sex does not match physician sex) has been associated with reduced clinical rapport and adverse outcomes including post-operative mortality and unplanned hospital readmission. It remains unknown whether patient-physician sex discordance is associated with “before medically advised” hospital discharge (BMA discharge; commonly known as discharge “against medical advice”).

Objective

To evaluate whether patient-physician sex discordance is associated with BMA discharge.

Design

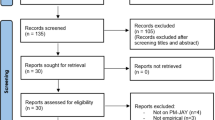

Retrospective cohort study using 15 years (2002–2017) of linked population-based administrative health data for all non-elective, non-obstetrical acute care hospitalizations from British Columbia, Canada.

Participants

All individuals with eligible hospitalizations during study interval.

Main Measures

Exposure: patient-physician sex discordance. Outcomes: BMA discharge (primary), 30-day hospital readmission or death (secondary).

Results

We identified 1,926,118 eligible index hospitalizations, 2.6% of which ended in BMA discharge. Among male patients, sex discordance was associated with BMA discharge (crude rate, 4.0% vs 2.9%; adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.08; 95%CI 1.03–1.14; p = 0.003). Among female patients, sex discordance was not associated with BMA discharge (crude rate, 2.0% vs 2.3%; aOR 1.02; 95%CI 0.96–1.08; p = 0.557). Compared to patient-physician sex discordance, younger patient age, prior substance use, and prior BMA discharge all had stronger associations with BMA discharge.

Conclusions

Patient-physician sex discordance was associated with a small increase in BMA discharge among male patients. This finding may reflect communication gaps, differences in the care provided by male and female physicians, discriminatory attitudes among male patients, or residual confounding. Improved communication and better treatment of pain and opioid withdrawal may reduce BMA discharge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Access to data provided by the Data Stewards is subject to approval, but can be requested for research projects through the Data Stewards or their designated service providers. All inferences, opinions, and conclusions drawn are those of the authors and do not reflect the opinions or policies of the Data Stewards.

References

Ibrahim SA, Kwoh CK, Krishnan E. Factors associated with patients who leave acute-care hospitals against medical advice. Am J Public Health. 2007 97(12):2204-8.

Tummalapalli SL, Chang BA, Goodlev ER. Physician practices in against medical advice discharges. J Healthc Qual. 2020 42(5):269-277.

Kleinman RA, Brothers TD, Morris NP. Retiring the “Against Medical Advice” Discharge. Ann Intern Med. 2022 175(12):1761-1762. https://doi.org/10.7326/M22-2964

Hwang SW, Li J, Gupta R, Chien V, Martin RE. What happens to patients who leave hospital against medical advice? CMAJ. 2003 168(4):417-20.

Alfandre DJ. “I’m Going Home”: Discharges Against Medical Advice. Mayo Clin Proc 2009 84(3):255-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-6196(11)61143-9.

Choi M, Kim H, Qian H, Palepu A. Readmission rates of patients discharged against medical advice: a matched cohort study. PloS One. 2011 6(9):e24459.

Southern WN, Nahvi S, Arnsten JH. Increased risk of mortality and readmission among patients discharged against medical advice. Am J Med. 2012;125(6):594–602.

Holmes EG, Cooley BS, Fleisch SB, Rosenstein DL. Against medical advice discharge: a narrative review and recommendations for a systematic approach. Am J Med. 2021 134(6):721-6.

Roter DL, Hall JA. Physician gender and patient-centered communication: a critical review of empirical research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004 25:497-519.

Greenwood BN, Carnahan S, Huang L. Patient-Physician Gender Concordance and Increased Mortality Among Female Heart Attack Patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(34):8569-8574. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1800097115

Mast MS, Hall JA, Roter DL. Disentangling physician sex and physician communication style: their effects on patient satisfaction in a virtual medical visit. Patient Educ Couns. 2007 68(1):16-22.

Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Orav EJ, Blumenthal DM, Tsai TC, Mehtsun WT, Jha AK. Age and sex of surgeons and mortality of older surgical patients: observational study. BMJ. 2018 Apr 25:361:k1343. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k1343.

Sandhu H, Adams A, Singleton L, Clark-Carter D, Kidd J. The impact of gender dyads on doctor–patient communication: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2009 76(3):348-55.

Wallis CJ, Jerath A, Coburn N, Klaassen Z, Luckenbaugh AN, Magee DE, Hird AE, Armstrong K, Ravi B, Esnaola NF, Guzman JC. Association of surgeon-patient sex concordance with postoperative outcomes. JAMA surgery. 2022 157(2):146-56.

Lin Z, Han H, Wu C, Wei X, Ruan Y, Zhang C, Cao Y, He J. Discharge against medical advice in acute ischemic stroke: the risk of 30-day unplanned readmission. J Gen Intern Med. 2021 36:1206-13.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. CIHI Portal — Discharge Abstract Database Metadata Dictionary. Ottawa, ON: CIHI; 2017.

Bell BA, Ferron JM, Kromrey JD. Cluster size in multilevel models: the impact of sparse data structures on point and interval estimates in two-level models. JSM proceedings, section on survey research methods. 2008 3:1122-9.

Barnsley J, Williams AP, Cockerill R, Tanner J. Physician characteristics and the physician-patient relationship. Impact of sex, year of graduation, and specialty. Can Fam Physician. 1999 45:935.

Southern WN, Bellin EY, Arnsten JH. Longer lengths of stay and higher risk of mortality among inpatients of physicians with more years in practice. Am J Med. 2011 124(9):868-74.

Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Quality of care delivered by general internists in US hospitals who graduated from foreign versus US medical schools: observational study. BMJ. 2017 3;356.

Roter DL, Hall JA, Aoki Y. Physician gender effects in medical communication: a meta-analytic review. JAMA. 2002 288(6):756-64.

Mast MS. On the importance of nonverbal communication in the physician–patient interaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2007 67(3):315-8.

Zolnierek KB, DiMatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009 47(8):826.

Schieber AC, Delpierre C, Lepage B, Afrite A, Pascal J, Cases C, Lombrail P, Lang T, Kelly-Irving M, INTERMEDE group. Do gender differences affect the doctor–patient interaction during consultations in general practice? Results from the INTERMEDE study. Fam Prac. 2014 31(6):706-13.

Gross R, McNeill R, Davis P, Lay-Yee R, Jatrana S, Crampton P. The association of gender concordance and primary care physicians’ perceptions of their patients. Women Health. 2008;48(2):123-144. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630240802313464

Bertakis KD. The influence of gender on the doctor–patient interaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2009 76(3):356-60.

Sergeant A, Saha S, Shin S, et al. Variations in Processes of Care and Outcomes for Hospitalized General Medicine Patients Treated by Female vs Male Physicians. JAMA Health Forum. 2021; 2 (7): e211615 https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.1615

Harris CR, Jenkins M. Gender differences in risk assessment: why do women take fewer risks than men?. Judgm Decis Mak. 2006 1(1):48-63.

Mather M, Lighthall NR. Risk and reward are processed differently in decisions made under stress. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2012 21(1):36-41.

Morgenroth T, Ryan MK, Fine C. The gendered consequences of risk-taking at work: are women averse to risk or to poor consequences?. Psychol Women Q. 2022 46(3):257-77.

Wallis CJ, Ravi B, Coburn N, Nam RK, Detsky AS, Satkunasivam R. Comparison of postoperative outcomes among patients treated by male and female surgeons: a population based matched cohort study. BMJ. 2017 10;359. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4366

Nosek BA, Smyth FL, Hansen JJ, Devos T, Lindner NM, Ranganath KA, Smith CT, Olson KR, Chugh D, Greenwald AG, Banaji MR. Pervasiveness and correlates of implicit attitudes and stereotypes. Eur Rev Soc Psychol. 2007 18(1):36-88.

Jost JT, Rudman LA, Blair IV, Carney DR, Dasgupta N, Glaser J, Hardin CD. The Existence of Implicit Bias Is Beyond Reasonable Doubt: a Refutation of Ideological and Methodological Objections and Executive Summary of Ten Studies That No Manager Should Ignore. Res Organ Behav. 2009 29:39-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2009.10.001

Adudu OP, Adudu OG. Do patients view male and female doctors differently?. East Afr Med J. 2007;84(4):172-7.

Fink M, Klein K, Sayers K, Valentino J, Leonardi C, Bronstone A, Wiseman PM, Dasa V. Objective data reveals gender preferences for patients’ primary care physician. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020 Jan-Dec;11:2150132720967221. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150132720967221.

Schreuder MM, Peters L, Bhogal-Statham MJ, Meens T, Roeters van Lennep JE. Male or female general practitioner; do patients have a preference? Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2019 Jan 14;163:D3146. Dutch.

Rowe SG, Stewart MT, Van Horne S, Pierre C, Wang H, Manukyan M, Bair-Merritt M, Lee-Parritz A, Rowe MP, Shanafelt T, Trockel M. Mistreatment experiences, protective workplace systems, and occupational distress in physicians. JAMA Network Open. 2022 5(5):e2210768-.

Health workforce in Canada: In focus (including nurses and physicians). CIHI Portal, Release November 17, 2022. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2023. https://www.cihi.ca/en/physicians. Accessed Mar 1, 2023.

Association of American Medical Colleges. Physician specialty data report. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/report/physician-specialty-data-report. Accessed 15 Dec 2022

Riner AN, Cochran A. Surgical outcomes should know no identity—the case for equity between patients and surgeons. JAMA Surgery. 2022 157(2):156-7.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Physicians in Canada, 2017. Ottawa, ON: CIHI; 2019. Accessed on July 10, 2023. Retrieved from: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/Physicians_in_Canada_2017.pdf

Imtiaz S, Hayashi K, Nolan S. An innovative acute care based intervention to address the opioid crisis in a Canadian setting. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2021 May;40(4):553-556. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13193.

Hu T, Snider-Adler M, Nijmeh L, Pyle A. Buprenorphine/naloxone induction in a Canadian emergency department with rapid access to community-based addictions providers. CJEM. 2019 21(4):492-8.

Marks LR, Munigala S, Warren DK, Liang SY, Schwarz ES, Durkin MJ. Addiction medicine consultations reduce readmission rates for patients with serious infections from opioid use disorder. Clin Infect Dis. 2019 68(11):1935-7.

Hyshka E, Morris H, Anderson-Baron J, Nixon L, Dong K, Salvalaggio G. Patient perspectives on a harm reduction-oriented addiction medicine consultation team implemented in a large acute care hospital. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019 204:107523.

Simon R, Snow R, Wakeman S. Understanding why patients with substance use disorders leave the hospital against medical advice: a qualitative study. Subst Abus. 2020 41(4):519-25.

Garcia JA, Paterniti DA, Romano PS, Kravitz RL. Patient preferences for physician characteristics in university-based primary care clinics. Ethn Dis. 2003 13(2):259-67.

Funding

This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant numbers PJT-180343 & PJT-183955), the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute Innovation and Translational Research Award (AWD-017961), and the UBC Division of General Internal Medicine. JAS was supported by a Health Professional-Investigator Award from Michael Smith Health Research BC. Funding organizations were not involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation and review of this abstract.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JAS and MK were responsible for study concept. All authors contributed to the study design. JAS and MK designed the analytic strategy. JAS was responsible for acquisition of the data. MK had full access to all study data and was responsible for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. YY and DD contributed to the data analysis. JAS and MK were responsible for drafting the manuscript. All authors were responsible for critical revisions of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, M., Yu, Y., Daly-Grafstein, D. et al. Patient-Physician Sex Discordance and “Before Medically Advised” Discharge from Hospital: A Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study. J GEN INTERN MED (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-08697-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-08697-8