Abstract

Background

Professional societies have recommended against use of self-monitoring blood glucose (SMBG) in non-insulin-treated type 2 diabetes (NITT2D) to control blood sugar levels, but patients are still monitoring.

Objective

To understand patients’ motivation to monitor their blood sugar, and whether they would stop if their physician suggested it.

Design

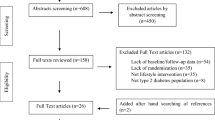

Cross-sectional in-person and electronic survey conducted between 2018 and 2020.

Participants

Adults with type 2 diabetes not using insulin who self-monitor their blood sugar.

Main Measures

The survey included questions about frequency and reason for using SMBG, and the impact of SMBG on quality of life and worry. It also asked, “If your doctor said you could stop checking your blood sugar, would you?” We categorized patients based on whether they would stop. To identify the characteristics independently associated with desire to stop SMBG, we performed a logistic regression using backward stepwise selection.

Key Results

We received 458 responses. The common reasons for using SMBG included the doctor wanted the patient to check (67%), desire to see the number (65%), and desire to see if their medications were working (61%). Forty-eight percent of respondents stated that using SMBG reduced their worry about their diabetes and 61% said it increased their quality of life. Fifty percent would stop using SMBG if given permission. In the regression model, respondents who said that they check their blood sugar levels because “I was told to” were more likely to want to stop (AOR: 1.69, 95%CI: 1.11, 2.58). Those that used SMBG due to habit and to understand their diabetes better had lower odds of wanting to stop (AOR: 0.33, 95%CI: 0.18–0.62; AOR: 0.60, 95%CI: 0.39–0.93, respectively).

Conclusions

Primary care physicians should discuss patients’ reasons for using SMBG and offer them the option of discontinuing.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Thirty million Americans have diabetes.1 Controlling diabetes through medications and lifestyle changes is important to reduce the likelihood of complications, such as cardiovascular disease, kidney and nerve damage, or skin infection.2, 3 One approach is for patients to self-monitor their blood glucose (SMBG) to understand their blood sugar levels and guide day-to-day food and exercise choices.4 Approximately 75% of patients with non-insulin-treated type 2 diabetes (NITT2D) report monitoring their blood glucose.5 The American Diabetes Association recommends (grade E-expert opinion) that SMBG “may be helpful when altering diet, physical activity, and/or medications.”6 However, a randomized trial of SMBG among NITT2D found no impact on glycemic control,7 and a systematic review found that the effect of SMBG is small in the first 6 months and does not persist over a year.8 SMBG is also expensive—with strips costing approximately $1 each, plus the cost of alcohol wipes and lancets.9 Not surprisingly, SMBG in NITT2D is not cost-effective for reducing diabetes-related complications.10 Therefore, as part of the Choosing Wisely campaign to reduce unnecessary tests and treatments, the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) recommends against SMBG in these patients.11 Physicians differ in their advocacy of SMBG with some believing it encourages patient-centered care and self-management of diabetes while others only prescribe it when asked.12 Patients also report that their clinicians’ attitude towards SMBG plays an important role in their monitoring frequency.13

Understanding which patients prefer to use SMBG and why is key to constructing a patient-centered approach to controlling diabetes. Some patients find SMBG helpful, and physicians report patients requesting to continue monitoring.12 In a qualitative study, patients stated that use of SMBG helps manage their diabetes by enabling them to build mental models and make self-management decisions.14 However, randomized trials of SMBG do not support that it improves patient satisfaction, quality of life, or well-being.7, 15 Use of SMBG has also been associated with increased levels of stress, worry, and depression.12, 16 Prior studies have been focused on whether SMBG impacted quality of life7, 17, 18 and have not assessed differences in preferences for use across a large sample of patients.

To understand patients’ motivation to monitor their blood sugar, and whether they would stop if their physician explicitly suggested it, we surveyed primary care patients with NITT2D who were using SMBG. We report patients’ stated reasons for performing SMBG and the percentage who said they would stop if given permission. We also compared responses of patients who would prefer to stop versus continue SMBG.

METHODS

This cross-sectional survey study included adults with NITT2D who received care at a primary care practice in a large integrated health system. Cleveland Clinic’s institutional review board approved this study.

Survey Recruitment

We recruited patients in person and via electronic survey. Collecting surveys in person is resource intensive, but yields a higher response rate. Electronic surveys can reach a large number of people, but with a lower response rate. By doing both, we limited response bias while increasing our study size. We reported the response rates for each mode of survey collection after removing ineligible patients from the denominator.

For the in-person portion, we excluded patients who were cognitively impaired, unable to provide consent, or non-English speaking. Research personnel recruited patients from a single internal medicine practice between November 2018 and March 2019. Patients were approached if their medical chart indicated that they had type 2 diabetes, were monitoring their blood sugar, and were not there for an urgent visit. As an incentive, patients who completed the survey received a $5 gift card.

The electronic survey was conducted between December 2019 and February 2020. We identified patients who met the eligibility criteria via chart review, and had an active MyChart account. We excluded patients approached for the in-person survey to ensure we did not approach the same patient twice. Survey invitations were sent via MyChart in five waves. Survey responses were recorded in RedCap. As an incentive, patients who completed the survey were offered a chance to win one of 20 $50 gift cards.

We excluded patients who indicated they used insulin or did not monitor their blood glucose in the past 2 months, or did not enter any demographic information.

Survey

We developed the survey based on interviews with physicians, literature review,13, 19,20,21,22 and expert opinion from healthcare providers. It was pilot tested for clarity and iteratively refined.

Survey respondents were asked about the frequency and timing of checking their blood sugar level, reasons for checking blood sugar, actions taken based on their readings, and the impact of checking blood sugar on quality of life and worry about diabetes. Respondents were able to select multiple reasons why they used SMBG and multiple actions taken based on the reading. Each individual response option was evaluated as “checked” versus not. Finally, we asked about age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, diabetic medication use, and number of years since diabetes diagnosis. Our primary outcome was the response to the question, “If your doctor said you could stop checking your blood sugar, would you?” The survey is included in the Supplementary Information.

We dichotomized questions related to quality and life, worry, and years with diabetes due to skewed distribution of responses. The question, “on the whole, checking my blood sugar makes my quality of life…” had 5 response options ranging from “a lot better” to “a lot worse.” We grouped patients who said SMBG made their life “a lot” or “a little” better compared to patients who said SMBG made their quality of life “the same,” “a little worse,” or “a lot worse.” For the question regarding worry, we grouped “does not affect how I feel” and “increases my worry” together versus “reduces my worry.”

Analysis

We compared responses across modalities (in-person versus electronic survey). After confirming that responses to our outcome variable were similar, we combined the datasets. We categorized patients based on whether they would quit and used the chi-squared test and regression analysis to compare responses across the groups. The logistic regression model initially included variables that were significant at the p<0.05 level in the bivariate analysis. We also included the survey questions regarding reasons for checking blood sugar, quality of life, and degree of worry. The final logistic regression model was created using backward selection of these variables. Since so few of our respondents had diabetes less than 1 year, we compared patients with diabetes less versus more than 5 years in the logistic regression. We used Stata 14.0 for the analysis.

Results

In total, 452 people responded to the survey. Our adjusted response rate was 65% (98/149) in person and 25% (354/1,830) online. A higher percentage of respondents who answered online versus in person were white (74% versus 20%). Respondents in both survey modalities had been diagnosed with diabetes for similar lengths of time, checked their blood sugar at similar frequencies and had similar desire to stop checking their blood sugar (Table 4 in the Appendix and Supplementary Information). Patient characteristics appear in Table 1. Overall, a majority of respondents were 65 years of age or older, female (56%), white (62%), and did not have a college degree (54%). Fifty-five percent of the respondents checked their blood sugar daily. Seventy-five percent of respondents reported that a good fasting blood glucose reading for them was between 80 and 130mg/dL and 92% took medications for their diabetes. The majority of respondents (58%) had been diagnosed with diabetes for more than 5 years and 8% were diagnosed within the last year.

Actions Taken After SMBG

In the last 2 months, 63% of respondents adjusted their diet based on their blood glucose readings, 30% changed their activity, and 27% made no changes (Table 2). In response to high glucose levels, 33% of respondents rechecked it, 55% adjusted their diet, 12% informed their doctor, and 14% took no action. After receiving a low reading, 23% rechecked their number, 67% ate something, and 8% of respondents informed their doctor. Fifty-eight percent of respondents said that a physician reviewed their recorded glucose numbers in the last 2 months.

Reasons for SMBG

The most common reason for SMBG was because a doctor requested it (67%). In order of frequency, other reasons for SMBG was to see the number (65%), to see if the diabetes medications are working (61%), to feel in control of diabetes (51%), to avoid damage due to diabetes (46%), to see if their sugar is low (40%), to understand their diabetes (38%), and because it is a habit (15%). Forty-eight percent of respondents stated that using SMBG reduced their worry about their diabetes and 61% said it increased their quality of life.

Stopping SMBG

Half of the respondents would stop checking their blood sugar if their physician said they could. A higher percentage of respondents who were diagnosed within 5 years would stop than respondents who have had diabetes for longer (59% versus 44%, p<0.01). Patients who would stop were less likely to report that they monitored their blood sugar at least daily (46% versus 66%; p<0.001), before bed (16% versus 26%, p=0.01), or after exercise (2% versus 7%, p =0.02) (Table 2). Patients who would not stop were more likely to report that SMBG improved their quality of life (71% versus 53%; p <0.001) and reduced their worry (55% versus 42%, p<0.05). We found no difference among patients who wanted to continue versus stop SMBG regarding how they responded to high or low sugar.

Patients’ reasons for monitoring their blood sugar were often significantly different among those who wanted to continue versus stop (Figure 1). Respondents who wanted to continue SMBG were more likely to do it to feel in control of their diabetes (60% versus 41%), to understand their diabetes better (46% versus 29%), and out of habit (22% versus 8%) (p≤0.02 for all comparisons).

In the adjusted model, wanting to stop was positively associated with checking blood sugar because “I was told to” (AOR:1.69, 95%CI: 1.11, 2.58) and negatively associated with SMBG due to habit (AOR: 0.33, 95%CI: 0.18–0.62), with reporting increased quality of life with SMBG (AOR: 0.51, 95%CI: 0.33–0.77) and using SMBG to understand their diabetes (AOR: 0.60, 95%CI:0.39–0.93) (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

SMBG is a powerful tool in the management of type 1 diabetes, allowing patients to carefully titrate insulin dosing to maintain euglycemia. In patients with type 2 diabetes who do not take insulin, the benefits of SMBG are less clear, and SGIM has recommended against routine use of SMBG.11 Nevertheless, the practice remains widespread, though the reasons for this are not well understood. In this study of SMBG among patients with NITT2D seen at a large integrated health system, we found that 91% of individuals reported that their doctor instructed them to check their blood sugar levels. More than half of patients checked their sugars daily and took some action in response to their blood sugar, most often making dietary adjustments. One-quarter of patients took no action at all. Many patients reported that checking their sugars improved their quality of life, gave them a sense of control, and reduced their worry. Despite these potential benefits, half of the patients said they would stop if their doctor told them they could. Respondents who wanted to continue were more likely to report that they used SMBG to feel in control of their diabetes and because it was a habit. There was no association between wanting to stop and taking action based on blood sugar readings.

Several randomized trials have found no difference in quality of life between patients randomized to SMBG and controls.7, 8, 17 In contrast, 61% of respondents in our study believed it did, and even respondents who wanted to stop SMBG often felt that way. It is possible that in the randomized trials, some patients had improved quality of life while others had a decrease, so that overall there was no change. In practice, however, patients who find that SMBG decreases their quality of life may stop monitoring, and therefore would not have been eligible to take our survey. Alternatively, individuals may come to believe that SMBG improves their quality of life to reduce the cognitive dissonance23 related to the time and financial commitment SMBG requires.24 Importantly, many respondents who reported that SMBG improved their quality of life would discontinue monitoring if their physician indicated that stopping was acceptable.

Proponents of SMBG for NITT2D suggest that it is useful to enable clinicians to make timely treatment adjustments and patients make lifestyle adjustments based on the pattern of glucose readings.25 In reality, it may be difficult for clinicians to make timely treatment decisions when only one-in-ten of our respondents reported contacting their physician in response to a low or high reading, and only 58% had shared their readings with a physician in the past 2 months. For medication adjustments, HbA1c measurements may be more appropriate. A higher percentage of patients reported changing their diet or exercising in response to blood glucose readings. While such changes could theoretically result in better glucose control, randomized trials do not support the practice long term.7, 26, 27 It is still possible that select patients who monitor frequently and make changes accordingly could benefit. Interviews with NITT2D patients who had significantly improved their glycemic control revealed that these individuals checked their levels at different times throughout the day and modified their activity regimen and dietary habits based on their measurements.28 However, more than 80% of our respondents checked their sugar in the morning, a reading that is not usually affected by eating, and only 24% measured their glucose after meals. Although continuous glucose monitors, which allow changes in glucose to be easily tracked over the day, may be more useful for making timely changes to diet and exercise based on blood glucose readings,29 this relatively new technology is expensive30 and is not currently recommended for use in NITT2D.

The use of SMBG is most beneficial in the first year after diabetes diagnosis in order to learn how to manage one’s diabetes.8 In our study, the vast majority of our respondents had diabetes for more than a year, and 58% had it for more than 5 years, surpassing the initial learning period when SMBG is the most beneficial. It appears that many patients practice SMBG out of habit, not because they find it beneficial but because their doctor continues to prescribe it and has not suggested they should stop. If primary care physicians are interested in avoiding low value services, it would make sense to skip SMBG altogether, or at the very least limit the duration of SMBG and revisit the need for SMBG among their current users.

For the group that wanted to continue monitoring, SMBG appeared to offer a feeling of control. This appears to be a novel finding and can help explain why some patients would prefer to continue SMBG. However, feeling in control is different than being in control. A cross-sectional survey of veterans with type 2 Diabetes found that higher levels of internal locus of control were associated with worse glycemic control.31 Similarly, a meta-analysis found that ascribing locus of control to oneself was uncorrelated with glycemic control.32 The PRISMA trial found that use of structured SMBG was not related to changes in locus of control at 12 months, but patients who had a longer duration of diabetes were more likely to report improved locus of control on the chance domain.17 Another approach would be to help patients with NITT2D develop self-efficacy, or belief that they could complete a particular action within a particular timeframe, because self-efficacy has been associated with greater HbA1c control33 and adherence to dietary recommendations.34

Less costly and less painful alternatives to SMBG may be useful for most patients and some might offer greater confidence in their ability to manage their health. Telephone self-management support and health coaching interventions have been shown to improve both self-care behaviors and quality of life among diabetic patients with limited health literacy.35 Having behavioral health specialists meet with diabetic patients following primary care visits can also decrease anxiety and depression related to their diagnosis.36 A meta-analysis of randomized control trials comparing psychological interventions aimed at reducing diabetic distress found low-quality evidence that they improved self-efficacy and HbA1c at 6 and 12 months compared to usual care.37 It may be time to refocus our limited healthcare resources on identifying ways to successfully discuss self-management approaches38 because the context in which information is presented can impact the likelihood that it will be adopted.

Our study has several limitations. Our response rate among individuals who received the survey via MyChart was low. We deployed the survey both in-person and online so we would have a high response rate among patients we approached in person and could reach a larger population of patients online. Since both groups had a similar desire to stop checking their blood sugar, frequency of checking their blood sugar and length of diabetes we believe the likelihood of non-response bias among the online patients was low. Another limitation is that data come from a single health system in Northeast Ohio and may not be generalizable to other settings. However, we were able to obtain larger sample of Black patients than in our overall Cleveland Clinic primary care population (approximately 77% White)39 through the in-person survey potentially increasing our external generalizability. Since, this was a cross-sectional study, respondents’ self-reported quality of life, degree of worry, and reason for using SBMG represent their feelings at the time of completing the survey and may have been different earlier in their disease course. We did not ask respondents about barriers to self-monitoring of blood glucose, including cost. Finally, since this was an anonymous survey, we could not link patient responses to clinical data.

CONCLUSION

Half of patients who self-monitor their blood sugar would stop if given permission by their physician. Patients with NITT2D who wanted to continue to monitor their blood sugar did so because it helped them to feel in control of their diabetes and because it was a habit. Given the expense related to SMBG, primary care physicians should reevaluate their patient’s SMBG benefits and discontinue it if possible.

References

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Type 2 Diabetes. Accessed October 9, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/type2.html

Herman WH, Ye W, Griffin SJ, et al. Early Detection and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Reduce Cardiovascular Morbidity and Mortality: A Simulation of the Results of the Anglo-Danish-Dutch Study of Intensive Treatment in People With Screen-Detected Diabetes in Primary Care (ADDITION-Europe). Dia Care. 2015;38(8):1449-1455. doi:https://doi.org/10.2337/dc14-2459

Stolar M. Glycemic Control and Complications in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. The American Journal of Medicine. 2010;123(3):S3-S11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.12.004

Benjamin EM. Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose: The Basics. Clinical Diabetes. 2002;20(1):45-47. doi:https://doi.org/10.2337/diaclin.20.1.45

Wang J, Zgibor J, Matthews JT, Charron-Prochownik D, Sereika SM, Siminerio L. Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose Is Associated With Problem-Solving Skills in Hyperglycemia and Hypoglycemia. Diabetes Educator. 2012;38(2):207-218. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721712440331

American Diabetes Association. 7. Diabetes Technology: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020. Dia Care. 2020;43(Supplement 1):S77-S88. doi:10.2337/dc20-S007

Young LA, Buse JB, Weaver MA, et al. Glucose self-monitoring in non-insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes in primary care settings: A randomized trial. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2017;177(7):920-929. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1233

Malanda UL, Welschen LMC, Riphagen II, Dekker JM, Nijpels G, Bot SDM. Self-monitoring of blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who are not using insulin. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;1:CD005060. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005060.pub3

Yeaw J, Lee WC, Aagren M, Christensen T. Cost of Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose in the United States Among Patients on an Insulin Regimen for Diabetes. JMCP. 2012;18(1):21-32. doi:https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2012.18.1.21

Cameron C, Coyle D, Ur E, Klarenbach S. Cost-effectiveness of self-monitoring of blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus managed without insulin. CMAJ. 2010;182(1):28-34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.090765

SGIM - Daily home finger glucose testing | Choosing Wisely. Accessed September 27, 2020. https://www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/society-general-internal-medicine-daily-home-finger-glucose-testing-type-2-diabetes-mellitus/.

Havele SA, Pfoh ER, Yan C, Misra-Hebert AD, Le P, Rothberg MB. Physicians’ views of self-monitoring of blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes not on insulin. Annals of Family Medicine. 2018;16(4):349-352. doi:https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2244

Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Hessler D, Edelman S V. A survey of blood glucose monitoring in patients with type 2 diabetes: are recommendations from health care professionals being followed? Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2011;27(sup3):31-37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1185/03007995.2011.599838

Despins LA, Wakefield BJ. Making sense of blood glucose data and self-management in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2020;29(13-14):2572-2588. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15280

Clar C, Barnard K, Cummins E, Royle P, Waugh N. Self-monitoring of blood glucose in type 2 diabetes: Systematic review. Health Technology Assessment. 2010;14(12):1-140. doi:https://doi.org/10.3310/hta14120

Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Hessler D, Edelman S V. What is so tough about self-monitoring of blood glucose? Perceived obstacles among patients with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetic Medicine. 2014;31(1):40-46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.12275

Russo GT, Scavini M, Acmet E, et al. The Burden of Structured Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose on Diabetes-Specific Quality of Life and Locus of Control in Patients with Noninsulin-Treated Type 2 Diabetes: The PRISMA Study. Diabetes Technology and Therapeutics. 2016;18(7):421-428. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2015.0358

Parsons SN, Luzio SD, Harvey JN, et al. Effect of structured self-monitoring of blood glucose, with and without additional TeleCare support, on overall glycaemic control in non-insulin treated Type 2 diabetes: the SMBG Study, a 12-month randomized controlled trial. Diabet Med. 2019;36(5):578-590. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.13899

Harris MI, Cowie CC, Howie LJ. Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose by Adults With Diabetes in the United States Population. Diabetes Care 1993 Aug;16(8):1116-23

Farmer A, Balman E, Gadsby R, et al. Frequency of self-monitoring of blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes: association with hypoglycaemic events. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2008;24(11):3097-3104. doi:https://doi.org/10.1185/03007990802473062

Barnard KD, Young AJ, Waugh NR. Self monitoring of blood glucose - a survey of diabetes UK members with type 2 diabetes who use SMBG. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:318. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-3-318

Evans JMM, Mackison D, Swanson V, Donnan PT, Emslie-Smith A, Lawton J. Self-monitoring among non-insulin treated patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Patients’ behavioural responses to readings and associations with glycaemic control. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;100(2):235-242. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2013.03.005

Redelmeier DA, Dickinson VM. Determining whether a patient is feeling better: pitfalls from the science of human perception. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(8):900-906. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1655-3

Malanda UL, Bot SD, Nijpels G. Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose in Noninsulin-Using Type 2 Diabetic Patients: It is time to face the evidence. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(1):176-178. doi:https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-0831

Polonsky WH, Fisher L. Self-monitoring of blood glucose in noninsulin-using type 2 diabetic patients: right answer, but wrong question: self-monitoring of blood glucose can be clinically valuable for noninsulin users. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(1):179-182. doi:https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-0731

Farmer AJ, Perera R, Ward A, et al. Meta-analysis of individual patient data in randomised trials of self monitoring of blood glucose in people with non-insulin treated type 2 diabetes. BMJ (Online). 2012;344(7847). doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e486

Towfigh A, Romanova M, Weinreb J, et al. Self-monitoring of blood glucose levels in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus not taking insulin: a meta-analysis - PubMed. Am J Manaf Care. Published 2008. Accessed November 27, 2020. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18611098/

Tanenbaum ML, Leventhal H, Breland JY, Yu J, Walker EA, Gonzalez JS. Successful self-management among non-insulin-treated adults with Type 2 diabetes: A self-regulation perspective. Diabetic Medicine. 2015;32(11):1504-1512. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.12745

Edelman SV, Cavaiola TS, Boeder S, Pettus J. Utilizing continuous glucose monitoring in primary care practice: What the numbers mean. Primary Care Diabetes. 2021;15(2):199-207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcd.2020.10.013

Funtanilla VD, Candidate P, Caliendo T, Hilas O. Continuous Glucose Monitoring: A Review of Available Systems. P T. 2019;44(9):550-553.

Williams JS, Lynch CP, Voronca D, Egede LE. Health locus of control and cardiovascular risk factors in veterans with type 2 diabetes. Endocrine. 2016;51(1):83-90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-015-0677-8

Hummer K, Vannatta J, Thompson D. Locus of control and metabolic control of diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Educ. 2011;37(1):104-110. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721710388425

Walker RJ, Smalls BL, Hernandez-Tejada MA, Campbell JA, Egede LE. Effect of diabetes self-efficacy on glycemic control, medication adherence, self-care behaviors, and quality of life in a predominantly low-income, minority population. Ethn Dis. 2014;24(3):349-355.

Xie Z, Liu K, Or C, Chen J, Yan M, Wang H. An examination of the socio-demographic correlates of patient adherence to self-management behaviors and the mediating roles of health attitudes and self-efficacy among patients with coexisting type 2 diabetes and hypertension. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1227. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09274-4

Ratanawongsa N, Handley MA, Sarkar U, et al. Diabetes health information technology innovation to improve quality of life for health plan members in urban safety net. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 2014;37(2):127-137. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/JAC.0000000000000019

Bickett A, Tapp H. Anxiety and diabetes: Innovative approaches to management in primary care. Experimental Biology and Medicine. 2016;241(15):1724-1731. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1535370216657613

Chew BH, Vos RC, Metzendorf M-I, Scholten RJ, Rutten GE. Psychological interventions for diabetes-related distress in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9:CD011469. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011469.pub2

Peek ME, Ferguson MJ, Roberson TP, Chin MH. Putting theory into practice: a case study of diabetes-related behavioral change interventions on Chicago’s South Side. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15(2 Suppl):40S-50S. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839914532292

Pantalone KM, Hobbs TM, Chagin KM, et al. Prevalence and recognition of obesity and its associated comorbidities: cross-sectional analysis of electronic health record data from a large US integrated health system. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11):e017583. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017583

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms. Jackie Fox and Ms. Toyomi Goto for their help recruiting patients, and Ms. Gina Rupp for her assistance sending out the electronic surveys.

Funding

This publication was made possible in part by the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland, KL2TR002547 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) component of the National Institutes of Health and NIH roadmap for Medical Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest..

Disclaimer

Contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pfoh, E.R., Linfield, D., Speaker, S.L. et al. Patient Perspectives on Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose When not Using Insulin: a Cross-sectional Survey. J GEN INTERN MED 37, 1673–1679 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07047-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07047-2