ABSTRACT

Background

Previous work has demonstrated that patients experience functional decline at 1–3 months post-discharge after COVID-19 hospitalization.

Objective

To determine whether symptoms persist further or improve over time, we followed patients discharged after hospitalization for severe COVID-19 to characterize their overall health status and their physical and mental health at 6 months post-hospital discharge.

Design

Prospective observational cohort study.

Participants

Patients ≥ 18 years hospitalized for COVID-19 at a single health system, who required at minimum 6 l of supplemental oxygen during admission, had intact baseline functional status, and were discharged alive.

Main Measures

Overall health status, physical health, mental health, and dyspnea were assessed with validated surveys: the PROMIS® Global Health-10 and PROMIS® Dyspnea Characteristics instruments.

Key Results

Of 152 patients who completed the 1 month post-discharge survey, 126 (83%) completed the 6-month survey. Median age of 6-month respondents was 62; 40% were female. Ninety-three (74%) patients reported that their health had not returned to baseline at 6 months, and endorsed a mean of 7.1 symptoms. Participants’ summary t-scores in both the physical health and mental health domains at 6 months (45.2, standard deviation [SD] 9.8; 47.4, SD 9.8, respectively) remained lower than their baseline (physical health 53.7, SD 9.4; mental health 54.2, SD 8.0; p<0.001). Overall, 79 (63%) patients reported shortness of breath within the prior week (median score 2 out of 10 (interquartile range [IQR] 0–5), vs 42 (33%) pre-COVID-19 infection (0, IQR 0–1)). A total of 11/124 (9%) patients without pre-COVID oxygen requirements still needed oxygen 6 months post-hospital discharge. One hundred and seven (85%) were still experiencing fatigue at 6 months post-discharge.

Conclusions

Even 6 months after hospital discharge, the majority of patients report that their health has not returned to normal. Support and treatments to return these patients back to their pre-COVID baseline are urgently needed.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

It is now clear that the impact of COVID-19 extends beyond the ramifications of acute illness such as hospitalization. Several studies have demonstrated persistent symptoms resulting in functional decline 1–3 months post-hospital discharge after admission for COVID-19.1,2,3,4,5 Patient-led research has also begun to describe a COVID-19 “long hauler” syndrome.6 To determine whether symptoms improve over time or persist, we followed a prospective cohort of patients discharged after admission for severe COVID-19 to characterize overall health status, physical and mental health, and dyspnea at 6 months post-hospital discharge. We compared patients’ responses at 6 months post-hospital discharge to their responses at 1 month post-hospital discharge and to their reported baseline before COVID-19 illness.

METHODS

This single health system observational cohort study has been previously described.7 Briefly, using the electronic health record (EHR) we screened consecutive COVID-19 discharges between April 15, 2020, and May 30, 2020, from hospitals in our health system. Our health system includes three hospitals admitting adult COVID-19 patients across urban and suburban settings and encompasses large academic quaternary-level hospitals and smaller community hospitals. Eligible patients were at least 18 years old who were hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2, required at minimum 6 l of supplemental oxygen (as documented in their EHR flowsheet) during their admission, had intact baseline cognitive and functional status, and were alive at the initial study contact. Patients who received supplemental oxygen via nasal cannula or other devices, non-invasive mechanical ventilation, or mechanical ventilation were included.

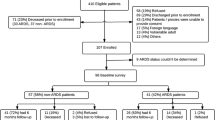

A total of 538 COVID-19 discharges were identified, of which 137 met exclusion criteria. Of the 397 remaining eligible discharges, 236 were not enrolled and 161 patients were consented. Additional enrollment details, including a flow diagram of enrolled participants, are detailed in our 1-month outcomes paper.7 Cohort characteristics such as age, sex, race, and language were obtained from the EHR.

Instruments

Data collection for patients’ baseline and 1-month scores has been previously described.7 Outcomes were obtained through validated PROMIS (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) survey instruments (see Supporting Information from the 1-month outcomes study).7 Baseline symptoms were elicited during the 1-month survey by prefacing the baseline questions with the following statement, “You will now answer the same questions again. This time, however, please answer them by thinking back to how you felt before you ever got sick with the coronavirus infection. Answer with the option that best fits how you usually felt in your day-to day life.” Six-month PROMIS items were identical to baseline and 1-month items, but were prefaced with the following statement, “I’m going to ask you a series of questions about how you’ve been feeling over the past 7 days. Please answer with the option that best fits how you’ve been feeling generally” (Appendix 1).

Overall health status and mental health were determined with the PROMIS® Global Health-10 instrument.8 Items in this 10-point standardized psychometric instrument are converted to a 5-point scale, in which higher scores indicate better health. Physical and mental health summary scores are produced using four items each. Raw scores for these domains are converted to normed t-scores. These scores are standardized such that a score of 509 represents the mean (standard deviation) for the US general population. The remaining two items relate to general health and how well social activities are carried out and are scored individually. If patients reported their health had not returned to baseline, we conducted a 22-point review of systems (ROS), in which patients were asked if they had experienced each symptom over the past week. The ROS list we developed is based on patient-reported symptoms shared by COVID-19 patient advocacy organizations.10 We aggregated the term “brain fog” with “cognitive fuzziness” and “difficulty concentrating” because while “brain fog” and “cognitive fuzziness” are not medical terms or diagnoses, they have emerged as frequent descriptors by patients to characterize their experiences.

Dyspnea outcomes at 6 months were elicited using the PROMIS® Dyspnea Characteristics instrument.9 The first four items use a 0–10 numeric rating scale (where 0 represents no shortness of breath and 10 represents the worst possible shortness of breath) and the last item uses a 5-point Likert scale (where 1 represents the participant has been short of breath “not at all” and 5 represents that the participant has been short of breath “very much”). The first item asks participants to rate their shortness of breath in general. If the participant has no shortness of breath, the instrument stops there and items 2–4 are assigned a score of 0, and item 5 is assigned a score of 1. If the participant reported shortness of breath, we asked the remaining four items, which address the intensity, frequency, duration, and severity of dyspnea. We conducted a subgroup analysis of patients who had shortness of breath prior to COVID-19, comparing their shortness of breath severity before and after COVID-19. We also conducted a subgroup analysis of patients who required intensive care unit (ICU) level care during hospitalization.

Statistical Analyses

We used the Wilcoxon signed rank test or paired t-test as appropriate to compare patients’ 6-month outcomes to their baseline and to their 1-month results. For score-based analyses, patients with incomplete surveys were excluded from the calculation of total scores. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All analyses were two-tailed and we treated a p value of <0.05 as significant.

RESULTS

Of 152 patients who completed the survey at 1-month post-discharge, 126 (83%) completed the 6-month survey (2 refused, 24 could not be reached). Non-responders at 6 months were slightly younger and more likely to be male but were otherwise similar to responders (Table 1). Six-month non-responders’ overall health status, physical and mental health, and dyspnea outcomes at baseline and 1 month (Appendix 2) were about the same or slightly better than 6-month respondents’ outcomes at those time points (Table 2). Review of our EHR for these 6-month non-respondents revealed no evidence that any of these patients died; however, we may have missed deaths occurring outside the health system.

Six-month survey completion occurred at a median of 188.5 days (range 180–235) after hospital discharge. Median age of 6-month respondents was 62 and 40% were female (Table 1). Forty-four (35%) received tocilizumab, and 17 (14%) received steroids. Initial D-dimer for this group was 419 (IQR 265–723) and first c-reactive protein was 141 (85–192). Over the past 6 months since hospital discharge after hospitalization for COVID-19, 19 (15%) patients reported an emergency department visit after hospital discharge, and 10 (8%) reported hospital readmission.

Ninety-three (74%) patients reported that their health had not returned to baseline at 6 months. Overall, patients reported worse general health (median score “good,” IQR “good” –“very good”) compared to baseline (median “very good,” IQR “good” –“excellent”), though slightly improved from 1-month post-discharge (median “good,” IQR “fair” –“very good,” p=0.034) (Table 2). Similarly, participants’ summary t-scores in both the physical health and mental health domains at 6 months (45.2, standard deviation [SD] 9.8; 47.4 SD 9.8, respectively) remained significantly lower than their baseline (physical health 53.7, SD 9.4; mental health 54.2 SD 8.0; p<0.001), and similar to 1-month post-discharge scores. However, there was slight improvement of physical health t-score at 6-month post-discharge compared to scores at 1-month post-discharge (45.2, SD 9.8 vs 43.3, SD 9.3, p=0.02). Mental health t-scores at 1-month post-discharge were not significantly different from scores at 6-month post-discharge.

Overall, 79 (63%) patients reported shortness of breath within the prior week with a median score 2 out of 10 (interquartile range [IQR] 0–5), vs 42 (33%) pre-COVID-19 infection (0, IQR 0–1), p<0.001 (Table 2). Among those with shortness of breath prior to COVID, the frequency of shortness of breath at 6-month post-discharge was worse compared to baseline, and not significantly changed since 1-month post-discharge. More patients also reported feeling short of breath “quite a bit” and “very much” at 6 months (16 [13%]) compared to before COVID-19 infection (2 [2%], p<0.001). A total of 11/124 (9%) patients without pre-COVID oxygen requirements still needed oxygen 6-month post-hospital discharge. Four of these patients reported needing at least 2 l/min of oxygen.

A total of 107 (85%) patients were still experiencing fatigue at 6-month post-discharge. Patients endorsed a mean of 7.1 other symptoms from the ROS list. Many patients were experiencing cognitive issues such as memory changes (52, 41%) and brain fog (47, 37%). Musculoskeletal issues such as weakness (58, 46%) were also prevalent (Table 2).

A larger proportion of patients who required ICU care reported that their health had not returned to baseline (47, 83%). However, dyspnea and PROMIS Global Health-10 outcomes were similar to the overall group (Appendix 3, Table 4). Likewise, while there was a greater range in baseline general shortness of breath for ICU patients, changes over time were similar to the overall group. None of the ICU patients used oxygen prior to COVID-19 infection, but 4/57 (7%) reported they still needed supplemental oxygen at 6 months (Table 3). ICU patients reported a median of 6 other symptoms from the ROS list. Prevalence of numbness/tingling, burning/pins/needles sensation, weakness, and muscle/body ache were slightly higher in the ICU subgroup compared to those in the overall group (Appendix 3, Table 5).

DISCUSSION

In this prospective cohort study of survivors of severe COVID-19, we found that even 6 months after hospital discharge, the majority of patients report that their health has not returned to baseline, and furthermore that it has not substantially improved from 1-month post-hospital discharge.

Consistent with other studies,11,12 shortness of breath, fatigue, cognitive issues, and musculoskeletal symptoms feature prominently in the constellation of problems reported by these survivors of severe COVID-19. It is unclear whether these sequelae are related to SARS-CoV-2 itself, a post-viral syndrome, complications from post-intensive care syndrome (over 45% of our cohort required intensive care), or prolonged hospital stays13 experienced by patients at the beginning of the pandemic (median length of stay for this group was 18.5 days).14 There is also increasing speculation that this syndrome may represent myalgic encephalomyelitis15; chronic fatigue syndrome has also previously been tied to SARS.16 Prior work on the long-term impact of SARS has demonstrated that despite some improvement in exercise capacity and health status at 6 months compared to 3 months post-acute illness, SARS survivors still experienced significant impairment even at 2 years after acute illness compared to normal controls.17 However, a 15-year follow-up showed that pulmonary interstitial damage and functional decline caused by SARS mostly recovered within 2 years after rehabilitation.18 Regardless, it is concerning that many symptoms have not improved even 6 months after hospital discharge, particularly since this group reported that prior to COVID-19 infection, their physical (mean t-score of 53.7) and mental health (mean t-score of 54.2) were slightly above the mean for the USA.8 Continued impaired health may have further downstream impact on the ability to return to work and regular life. Indeed, given the known impact of post-intensive care syndrome on patient recovery, there is growing concern that there will be a subsequent public health crisis if this syndrome is not treated.19,20

Development of tailored, evidence-based rehabilitation interventions to facilitate these patients’ functional recovery is ongoing. The World Health Organization observes that COVID-19 is a multisystem disease, and a multidisciplinary team may be needed to direct some patients’ recovery.21 COVID-19-related symptoms such as fatigue, musculoskeletal symptoms, and cognitive issues may affect ability to complete activities of daily living (ADL); thus, ADL training, additional caregiver support, home modifications, and assistive devices may all be needed to support patients as they regain strength. Additional expert opinion-based recommendations22,23 on how to manage patients with “long COVID-19” include medical evaluation to identify a more specific etiology of this syndrome, referral to pulmonary rehabilitation, or mental health services. Policy supporting these patients during this time of compromised physical and mental health (such extended sick leave or accommodations at work) should also be provided, particularly as the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, which provided some expanded paid sick leave benefits, has now expired.24

Study strengths include use of validated instruments and prospective follow-up of a pre-established cohort over time with a high response rate,25 in contrast to studies relying on patients self-reporting symptoms. Limitations include relatively small sample size, subjective report of symptoms, which may be subject to bias, no objective measurement of pulmonary function, and single-center design. In addition, this study was not powered to perform multivariable regression analyses to identify if factors such as hospital length of stay or other patient characteristics may be associated with worse outcomes. Finally, the study included only patients with severe COVID-19.

In conclusion, we found that patients discharged after hospitalization for severe COVID-19 still experience symptoms that may affect their quality of life even 6 months after discharge. Support and treatment are needed to return these patients back to their pre-COVID baseline.

References

Zhao Y-m, Shang Y-m, Song W-b, et al. Follow-up study of the pulmonary function and related physiological characteristics of COVID-19 survivors three months after recovery. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;25:100463.

Chopra V, Flanders SA, O'Malley M, Malani AN, Prescott HC. Sixty-Day Outcomes Among Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2020.

Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F, Group ftGAC-P-ACS. Persistent Symptoms in Patients After Acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020.

Weerahandi H, Hochman KA, Simon E, et al. Post-discharge health status and symptoms in patients with severe COVID-19. JGIM (in press). 2020.

Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. The Lancet. 2021;397(10270):220-232.

Assaf G DH, McCorkell L, et al. What does COVID-19 recovery actually look like? May 11, 2020 2020.

Weerahandi H, Hochman KA, Simon E, et al. Post-Discharge Health Status and Symptoms in Patients with Severe COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(3):738-745.

PROMIS. GLOBAL HEALTH: A brief guide to the PROMIS© Global Health instruments:. PROMIS® Scoring Manuals 2017; http://www.healthmeasures.net/images/PROMIS/manuals/PROMIS_Global_Scoring_Manual.pdf. Accessed 15 Oct 2020

PROMIS. DYSPNEA: A brief guide to the PROMIS© Dyspnea instruments. PROMIS® Scoring Manuals 2017; http://www.healthmeasures.net/images/PROMIS/manuals/PROMIS_Dyspnea_Scoring_Manual.pdf. Accessed 15 Oct 2020

Patient-Led Research Collaborative. About the Patient-Led Research Collaborative. https://patientresearchcovid19.com/. Accessed 5/5/2021, 2021.

Cellai M, O’Keefe JB. Characterization of Prolonged COVID-19 Symptoms in an Outpatient Telemedicine Clinic. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2020;7(10).

Halpin SJ, McIvor C, Whyatt G, et al. Postdischarge symptoms and rehabilitation needs in survivors of COVID-19 infection: A cross-sectional evaluation.n/a(n/a).

Martinez MS, Robinson MR, Arora VM. Rethinking Hospital-Associated Disability for Patients With COVID-19. Journal of hospital medicine. 2020;15(12):757-759.

Fraser E. Long term respiratory complications of covid-19. 2020;370:m3001.

Perrin R, Riste L, Hann M, Walther A, Mukherjee A, Heald A. Into the looking glass: Post-viral syndrome post COVID-19. Med Hypotheses. 2020;144:110055-110055.

Lam MH-B, Wing Y-K, Yu MW-M, et al. Mental Morbidities and Chronic Fatigue in Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Survivors: Long-term Follow-up. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009;169(22):2142-2147.

Ngai JC, Ko FW, Ng SS, To K-W, Tong M, Hui DS. The long-term impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on pulmonary function, exercise capacity and health status. Respirology. 2010;15(3):543-550.

Zhang P, Li J, Liu H, et al. Long-term bone and lung consequences associated with hospital-acquired severe acute respiratory syndrome: a 15-year follow-up from a prospective cohort study. Bone Research. 2020;8(1):8.

Jaffri A, Jaffri UA. Post-Intensive care syndrome and COVID-19: crisis after a crisis? Heart Lung. 2020;49(6):883-884.

Biehl M, Sese D. Post-intensive care syndrome and COVID-19 — Implications post pandemic. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 2020.

World Health O. COVID-19 clinical management: living guidance, 25 January 2021. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021 2021.

Greenhalgh T, Knight M, A’ Court C, Buxton M, Husain L. Management of post-acute covid-19 in primary care. 2020;370:m3026.

Landi F, Gremese E, Bernabei R, et al. Post-COVID-19 global health strategies: the need for an interdisciplinary approach. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research. 2020;32(8):1613-1620.

United States Department of Labor. Families First Coronavirus Response Act: Employee Paid Leave Rights. 2020; https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/pandemic/ffcra-employee-paid-leave. Accessed 12/5/2020, 2020.

Fincham JE. Response rates and responsiveness for surveys, standards, and the Journal. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(2):43-43.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Caroline Blaum, MD; Amy Bleasdale; Joshua Chodosh, MD, MSHS; Jacqueline L. Heath, MD; Savannah Karmen-Tuohy, Lindsey Quintana; Jennifer Rutishauser; Leticia Santos Martinez, MPH; Kanan Shah; Elias Simon; Emma Simon and Ana Stirniman for their contributions and Pacific Interpreters for providing free interpretation services for this study.

Funding

Dr. Weerahandi is supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health (K23HL145110).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The National Institutes of Health had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Horwitz, L.I., Garry, K., Prete, A.M. et al. Six-Month Outcomes in Patients Hospitalized with Severe COVID-19. J GEN INTERN MED 36, 3772–3777 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07032-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07032-9