Abstract

Background

Implementation science (IS) and quality improvement (QI) inhabit distinct areas of scholarly literature, but are often blended in practice. Because practice-based research networks (PBRNs) draw from both traditions, their experience could inform opportunities for strategic IS-QI alignment.

Objective

To systematically examine IS, QI, and IS/QI projects conducted within a PBRN over time to identify similarities, differences, and synergies.

Design

Longitudinal, comparative case study of projects conducted in the Oregon Rural Practice-based Research Network (ORPRN) from January 2007 to January 2019.

Approach

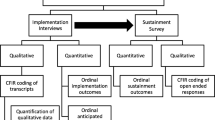

We reviewed documents and conducted staff interviews. We classified projects as IS, QI, IS/QI, or other using established criteria. We abstracted project details (e.g., objective, setting, theoretical framework) and used qualitative synthesis to compare projects by classification and to identify the contributions of IS and QI within the same project.

Key Results

Almost 30% (26/99) of ORPRN’s projects included IS or QI elements; 54% (14/26) were classified as IS/QI. All 26 projects used an evidence-based intervention and shared many similarities in relation to objective and setting. Over half of the IS and IS/QI projects used randomized designs and theoretical frameworks, while no QI projects did. Projects displayed an upward trend in complexity over time. Project used a similar number of practice change strategies; however, projects classified as IS predominantly employed education/training while all IS/QI and most QI projects used practice facilitation. Projects including IS/QI elements demonstrated the following contributions: QI provides the mechanism by which the principles of IS are operationalized in order to support local practice change and IS in turn provides theories to inform implementation and evaluation to produce generalizable knowledge.

Conclusions

Our review of projects conducted over a 12-year period in one PBRN demonstrates key synergies for IS and QI. Strategic alignment of IS/QI within projects may help improve care quality and bridge the research-practice gap.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Over two decades ago, the National Academy of Medicine (then Institute of Medicine) published a foundational report focused on “crossing the quality chasm” in healthcare.1 Since then, a robust body of literature and multiple national initiatives have focused on improving the quality of care in routine practice.2,3,4,5 Two relatively isolated fields—implementation science (IS) and quality improvement (QI) science—have developed theories and methods to address, optimize, and evaluate change in clinical practice (see definitions in Figure 1). IS offers strategies to promote uptake of evidence-based practices in order to improve the quality of care as well as to produce generalizable knowledge.6,7,8 QI—or more recently improvement science—originated from industry and aims to increase the quality, value, and safety of healthcare by changing specific processes within a specific healthcare system/setting.7,8,9,10

A number of recent articles focus on distinctions between IS and QI.7, 8, 11 However, a growing body of research articulates alignment and potential synergies for these fields. Within cancer care delivery research, Koczwara and colleagues suggest that although IS and QI emerged from different scientific orientations and have fought for intellectual differentiation, in reality they present complementary and synergistic approaches to support practice change.10 Within the nursing literature, Granger (2018) identifies growing semantic entanglement between these fields and focuses on articulating their distinctions,11 while simultaneously citing prior work by her team that combines these approaches within the same studies.12, 13 Check and colleagues reviewed 20 highly cited cancer-related IS and QI studies published in the last 5 years and concluded that “studies use different terminology and emphasize different methodological aspects in reporting but share similarities in purpose, scope, and methods, and are at similar levels of scientific development” and were “well-positioned for alignment.”14

Practice-based research networks (PBRNs) provide an opportunity to empirically explore the application of IS, QI, and IS/QI in actual practice. Practice-based research networks (PBRNs) originated in the 1970s as groups of primary care clinicians and academic researchers affiliated to investigate questions of importance to their clinics and patients.15, 16 In 1994, there were 28 active PBRNs in North America;17 as of August 2020, 185 PBRNs were registered with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).18 PBRN structure supports ongoing commitment to network members that transcends a single research project, is focused on linking community-based clinicians with academic investigators, and helps build the capacity of members over time.19 Much of the PBRN literature has highlighted the integration of research and QI as standard practice.2, 19,20,21,22 However, no studies that we are aware of have explored how PBRNs have conducted IS and QI over multiple years of network existence or the contribution of these approaches within the same projects.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to systematically examine IS and QI projects over a 12-year period within one PBRN, the Oregon Rural Practice-based Research Network (ORPRN).23 Our goal was to address three research questions: (1) How are IS, QI, and IS/QI projects similar or different?; (2) How have IS, QI, and IS/QI projects changed over time?; and (3) In blended IS/QI projects, what synergies exist between the two approaches? We hypothesized that the majority of studies included in the review would include elements of IS and QI and would use IS to inform intervention selection and evaluation and QI to support local practice change. We anticipate this analysis will advance key gaps in IS and QI literature (namely the interface between these fields), describe how PBRNs draw from both approaches, and advance development of implementation laboratories.

METHODS

We conducted a longitudinal, comparative case study to explore IS and QI projects within one PBRN. Data abstraction and analysis modeled best practices for systematic reviews.24 The Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board classified this study as non-human subjects research (IRB #20370).

Setting

ORPRN was founded in 2002 with a focus on rural clinics, but expanded in 2010 to engage clinics throughout the state.25 As of October 2020, ORPRN employed 41 staff, including 14 regionally based practice facilitators26, 27 charged to maintain community relationships while supporting network projects. Between 2014 and 2019, ORPRN engaged more than 360 primary care clinics in more than 84 research, technical assistance, and improvement projects (see network map in Appendix 1). Clinics displayed diversity in ownership, clinic size, and electronic health records. Roughly 56% of these clinics were system-owned, 10% were classified as Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs),28 and nearly 50% were located in rural/frontier areas.29, 30

Over time, ORPRN’s projects have evolved with the changing healthcare landscape, including an increase in hospital/health system–owned clinics, use of electronic health records, quality metric performance and value-based care, and integration of clinical team members (e.g., community health workers).31,32,33 Like many PBRNs, ORPRN adapted by engaging new health system partners (e.g., payers, hospital administrators) and embracing the principles of community-based participatory research (CBPR).19, 34, 35 ORPRN also affiliated into a meta-network of PBRNs to enable the conduct pragmatic clinical trials, comparative effectiveness research, and improve access for big data analyses.36,37,38,39

Project Identification and Inclusion

One co-author (CD) identified all projects and studies (henceforth referred to as projects for simplicity) conducted in ORPRN from network inception. This list was finalized by the lead author (MMD) based on a secondary review of ORPRN’s digital project folders and faculty CVs. We excluded projects initiated prior to 2007 because we lacked access to complete records; included projects thus spanned a 12-year period from January 2007 through January 2019.

To classify project type, we used definitions informed by Bhattacharyya and colleagues for IS6 and Batalden & Davidoff for QI9, and accounted for recent articles comparing and contrasting these methods7, 8, 10 (see Figure 1). Two authors (MMD, LM) reviewed the titles and descriptions of eligible projects and made a preliminary classification of each as IS, QI, IS/QI, or other based on the original applications. From the initial list of included projects, three authors (CD, RG, CC) independently reviewed 12–14 projects each, abstracting data and making a secondary classification. We used the following pragmatic definitions: a project was classified as IS if it evaluated efforts to promote the adoption of an evidence-based intervention into practice and produced generalizable knowledge and QI if it evaluated efforts to improve the quality, value, or safety of care in specific settings. Projects including both elements were classified as blended IS/QI. One author (MMD) compared preliminary and secondary classifications. We reconciled discrepancies via group discussion; if consensus was not achieved, the senior author (NE) adjudicated the final decision. We excluded projects classified as other—which included infrastructure development awards, demonstration projects, formative research, and research to generate new evidence—to facilitate direct comparison between IS, QI, and IS/QI projects as specified by our research questions.

Data Collection and Analysis

We developed an abstraction template informed by the Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI),40 Statement and Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting (SQUIRE)41, and prior work exploring the interface between IS and QI (see Appendix 2).10, 42 Data abstracted included details on the funding source, start/end years, objective, topic, design, setting, evidence-based practice, theoretical framework, and practice change strategies. In relation to theoretical framework, we included any mention of theories, models, or frameworks used to inform the implementation process, explain outcomes, or to support evaluation.43 To classify practice change strategies, our team developed an a priori list of common implementation strategies used by ORPRN (e.g., practice facilitation, education/training, process improvement) and added strategies inductively during abstraction (e.g., community engagement, technology system changes). Although categories were informed by the work of Powell and colleagues, we used the term practice change strategy to align with prior work and because the strategies observed rarely used individual implementation strategies or with existing strategy clusters.14, 44, 45

We gathered data via two sources: documents and informal interviews with ORPRN staff. Documents (e.g., applications, planning documents, manuscripts, reports) were the primary information source. We also conducted informal interviews by phone, email, or in person with the PI or project manager when necessary to clarify missing details (e.g., funding source, practice change strategies). One author (MMD) reviewed all abstracted information for accuracy and assessed project complexity on four dimensions (stakeholder number, geographic location, and variety of interests as well as project interdependencies) using a scale modified from Vidal and colleagues (see criteria in Appendix 3).46

The study team characterized and compared the 26 included projects in relation to each research question through a series of weekly review meetings. We utilized qualitative synthesis, which included integrated and interpretive methods, to draw conclusions.47 The study team identified and drafted a case example in order to illustrate how IS and QI elements manifest in the same project and to highlight potential synergies.

RESULTS

Included Studies

As detailed in Figure 2, 23% of the projects (23/99) occurred at ORPRN prior to 2007 and were excluded due to incomplete access to project information. After title and preliminary review, 38 projects underwent full review and 26 were included in the final analysis (see Appendixes 4 and 5). Included projects were classified as IS (n=4), QI (n=8), and IS/QI (n=14).

Characteristics

As noted in Table 1, projects addressed preventive services (e.g., cancer screening, vaccinations), care delivery models (e.g., patient-centered medical home, integrated care), specific diseases, geriatric topics, and medication management. Projects averaged 3.8 years in length; IS and QI projects were slightly shorter on average (3.3 and 3.0 years respectively) than those coded as IS/QI (4.4 years). Thirteen agencies funded these projects, including federal sources, national foundations, and local sources including state agencies and health plans.

Objectives, Setting, and Design

All 26 projects used evidence-based interventions (see Table 1). Half focused on implementing programs while the remaining focused on improving clinical care practices (27%) or increasing guideline concordant care (23%). Implementation of evidence-based programs was most common for projects categorized as IS/QI (71%) compared to IS (25%) or QI (25%).

Projects primarily occurred in primary care (50%) or engaged clinics and community settings (46%). The number of sites involved in projects varied widely, from a minimum of a single clinic to as many as 130 (see Appendix 4). Notably, 81% of projects occurred only in ORPRN. The three projects that involved multiple PBRNs were either classified as IS (1/4) or IS/QI (2/14). Half of the projects classified as IS or IS/QI used randomized designs while no QI projects did. IS/QI-classified projects also used staggered implementation designs (29%), pre/post (14%), and technical assistance support (7%).

As portrayed in Figure 3, projects had an upward trend in complexity over time, driven by an increase in the diversity of the geographic location of stakeholders, the number of stakeholders involved, and the variety of stakeholder interests. Increased complexity occurred for all project classifications (see Appendix 6).

Theoretical Basis and Practice Change Strategies

As detailed in Table 1 and Appendix 4, almost half of the projects (12/26) did not specify a theoretical framework. Theories were common in IS (50%) and IS/QI (86%) projects, while no QI projects included them. RE-AIM48 was used in three projects (12%); the following frameworks appeared in two projects each: the Solberg model,49 the Chronic Care model,50 and the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR).51 Four projects integrated two or more frameworks.

On average, 3.5 practice change strategies were used per project with practice facilitation as the most prevalent (81%, see Appendix 5). Other practice change strategies used in more than half of the projects included education/training (73%), process improvement (62%), and performance data in the form of audit and feedback or clinical quality reports (62%). All IS/QI projects used practice facilitation as did the majority classified as QI (75%) while only one IS project did (25%). All IS projects used education/training and the majority used performance data (75%).

Unique and Synergistic Contributions

Review of the projects classified as IS revealed a pattern of “top down” features in that an intervention and/or improvement target was driven at least in part by the research team or funding announcement. IS projects often utilized theoretical frameworks and prioritized the collection and synthesis of findings across participating sites. QI projects displayed “bottom up” features in that local stakeholders were involved in the selection of intervention and/or improvement targets and a focus on enabling change within a specific setting. QI-classified projects also focused on alignment to local context/needs and utilized rapid implementation processes to support change and to build clinic capacity. IS/QI projects displayed both of these elements by encouraging a focus on locally tailored improvement couched within rigorous cross-project evaluations to produce generalizable knowledge.

The case example in Figure 4 of AHRQ’s EvidenceNOW Healthy Hearts Northwest (H2N) initiative demonstrates how elements of IS and QI were often integrated within the same project. H2N was designed to help 250 small- to medium-sized primary care clinics in Oregon, Washington, and Idaho improve care to address cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., aspirin, blood pressure, cholesterol, and smoking) by implementing the latest evidence-based interventions (IS components). H2N was designed to enable an evaluation by the research team and participation in a cross-project evaluation to determine which change strategies were most effective (IS components). However, the case also describes how the practice facilitator focused on prioritizing change within a specific setting, illustrated in the focused work with clinic Z (QI components). Specifically, the practice facilitator did this by taking the overall project guidance for change, assessing the context of the larger health system and needs of the specific clinic, and tailoring their approach over time. For work with clinic Z, the facilitator served as a bridge between the larger health system’s centralized QI team and this individual clinic. Specifically, they helped the clinic review the current evidence; consider innovative changes that had worked in other clinics and to identify improvement priorities; overcome organizational barriers and gain access to data to inform improvement; and set improvement targets and utilize iterative QI cycles to enhance protocols and improve their metrics (QI components). Ultimately, this clinic became the top-performing clinic on the blood pressure metric within the health system.

Many of the IS/QI projects displayed similar methods for bringing elements of IS and QI together, as displayed in the case example (Fig. 4). One IS/QI project focused on integrating clinic and community programs to manage obesity (aka CLEMENTE) included QI elements in that the topic was a local priority, the interventions were operationalized based on locally available resources, and PDSA cycles were utilized to improve referral processes over time. In addition, a cross-project evaluation found that linkages were most effective when staff or clinicians bridged between the clinic and community-based settings through employment or volunteer roles with the referral programs. Another project, classified as QI only (CLIPS), was designed as an IS project at the time of funding, but never brought the cross-project evaluation to fruition. Thus, local contexts changed care delivery, but data were never utilized to produce generalizable findings to inform future implementation efforts. While these patterns repeated for many projects, the study team noted multiple challenges distinguishing between IS and QI studies because of similarities in the definition, setting, and methods used for evaluation.

DISCUSSION

We analyzed 26 projects classified as IS, QI, or IS/QI that were conducted in one PBRN (ORPRN) over a 12-year period; over half (53.8%) were classified as IS/QI. Many characteristics of IS, QI, and IS/QI studies were similar. Notably, all studies focused on implementing evidence-based practices, programs, or guidelines. However, half of the IS or IS/QI projects used randomized designs while none classified as QI did. None of the QI used theories to inform implementation or evaluation, compared to 86% of the IS/QI projects and 50% of the IS projects. The number of practice change strategies used were similar across all classification types; however, practice facilitation was most common in QI and IS/QI projects while education and training were used in all IS projects. Regardless of classification type, all projects displayed an upward trend in complexity over time based on an increase in the number of stakeholders involved, variety of interests, and diversity in geographic location.

In our longitudinal comparative case study review, projects that included both IS and QI elements—such as illustrated in the case example in Figure 4—did not only enable local practice change through QI efforts but also provided data to help evaluate implementation and to provide generalizable findings to inform future work. As illustrated in the case example, one can rarely do IS (integrate evidence into practice) without at least some QI (the local, applied, relational approach that turns ideas into actions). In addition, efforts from QI can be lost if they are not rigorously evaluated using IS methods to compare across sites in order to help determine what works, when, and why.

Figure 5 presents the synergistic benefits of IS and QI, and the iterative relationship between them, which emerged from our review of projects conducted within one PBRN. In contrast to prior work suggesting that QI is outside of implementation research,52 our study demonstrates how the two approaches can and should be brought into alignment. QI can be considered the mechanism by which the principles of IS are operationalized in order to support local practice change. IS in turn provides theories to inform implementation, evaluate efforts to produce generalizable knowledge (e.g., monitor issues of intervention fidelity and the role of context, identify determinants that influence the success or failure of efforts), and to disseminate findings to help others seeking to make similar changes. Integrating IS and QI within the same projects present opportunities to enhance the implementation and sustainability of research in practice. Such approaches align with the concepts from participatory implementation science, the learning evaluation approach, and recent work highlighting methods to systematically integrate IS and QI within projects to facilitate research translation.12, 13, 53,54,55,56

Implementation strategies—or in our case “practice change strategies” to account for bundling—are an important element of both IS and QI which warrant additional study. Practice facilitation was used in 81% of the included projects. A growing body of evidence supports the effectiveness of practice facilitation in helping clinics implement clinical guidelines or improve care delivery.57, 58 Practice facilitators are trained professionals who use organizational development, project management, QI, and practice improvement methods to build the internal capacity of a clinic while helping supporting practice change initiatives.26, 27, 59 While facilitation is identified as one of 73 implementation strategies by Powell and colleagues,44, 45 PBRNs routinely use practice facilitation as a central and unifying approach to deploy practice change strategies that are tailored to local context and stakeholder needs.27 This may be because facilitators serve as boundary spanners between the type 1 (slow, systematic) thinking used to create evidence-based programs and interventions and the type 2 (automatic) thinking that occurs in practice.60 Richie and colleagues have described facilitation as a “meta-strategy” for implementation in that facilitators assess local contexts, help adapt interventions, and deploy tailored practice change strategies based on local priorities and needs61 and facilitation is the active ingredient of the integrating Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (iPARIHS) framework.62

There are a few notable limitations of the current study. First, our review was limited to projects conducted over a 12-year period (2007–2019) within one PBRN. ORPRN is an established PBRN with nearly two decades of experience supporting research and QI initiatives, and findings may vary for new or smaller PBRNs. Second, we excluded projects that were not classified as IS, QI, or IS/QI. We speculate that although these projects were not specifically designed to change practice, they likely set an important foundation for future IS and QI efforts. Additionally, “non-implementation studies” may be less demanding on practices and PBRN staff and thus provide opportunities to build the resilience needed to support practice change. Third, our description of theoretical frameworks was inclusive of frameworks used at any point (e.g., from implementation process to evaluation)43 and did not evaluate the impact process or implementation frameworks had on outcomes. Finally, our classification of studies as IS, QI, or IS/QI was difficult given the similarities in these approaches and differences in language and reporting.10, 42 Our team addressed this challenge by returning to the definitions for IS and QI identified in Figure 1, pragmatically defining elements of IS and QI projects, using multiple reviewers and group discussions to reconcile differences in coding, and conducting informal interviews with ORPRN staff in order to clarify gaps and/or locate additional project documents. Despite these limitations, our results provide important insight into how IS and QI elements often appear within the same projects and create potential synergies.

Future research could explore IS and QI characteristics in the full spectrum of projects conducted within PBRNs and to see if similar patterns emerge in other settings conducting pragmatic research such as in learning healthcare systems or other implementation laboratories. Research is also needed to test associations between theoretical frameworks, practice change strategies, and study outcomes to inform best practices and mechanisms of action in IS/QI projects.63

CONCLUSION

Implementation science (IS) and quality improvement (QI) are two approaches designed to improve clinical practice. While frequently viewed as distinct disciplines, our review found that the majority of projects conducted in one PBRN over a 12-year period included elements of both IS and QI. IS and QI provide complementary tools to help clinics integrate evidence-based practice, programs, and guidelines into routine clinical care. IS provides robust research evidence while QI provides a process by which to effectively engage and interact with local contexts. In turn, IS supports rigorous evaluations of these local QI efforts to support identification of what works and why, and to disseminate findings beyond individual settings. Strategic alignment of IS/QI within projects may help bridge the gap between scientific discoveries and routine practice.

References

Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in A. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). Copyright 2001 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved; 2001.

Westfall JM, Mold J, Fagnan L. Practice-Based Research—“Blue Highways” on the NIH Roadmap. JAMA. 2007;297(4):403-406.

Balas EA, Boren SA. Managing Clinical Knowledge for Health Care Improvement. Yearb Med Inform 2000(1):65-70.

Fagnan LJ, Davis M, Deyo RA, Werner JJ, Stange KC. Linking practice-based research networks and Clinical and Translational Science Awards: new opportunities for community engagement by academic health centers. Acad Med 2010;85(3):476-483.

Riley-Behringer M, Davis MM, Werner JJ, Fagnan LJ, Stange KC. The Evolving Collaborative Relationship between Practice-Based Research Networks (PBRNs) and Clinical and Translational Science Awardees (CTSAs). J Clin Transl Sci 2017;1(5):301-309.

Bhattacharyya O, Reeves S, Zwarenstein M. What Is Implementation Research?:Rationale, Concepts, and Practices. Res Soc Work Pract 2009;19(5):491-502.

Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol 2015;3:32.

Holtrop JS, Rabin BA, Glasgow RE. Dissemination and Implementation Science in Primary Care Research and Practice: Contributions and Opportunities. J Am Board Family Med 2018;31(3):466-478.

Batalden PB, Davidoff F. What is "quality improvement" and how can it transform healthcare? Qual Saf Health Care 2007;16(1):2-3.

Koczwara B, Stover AM, Davies L, et al. Harnessing the Synergy Between Improvement Science and Implementation Science in Cancer: A Call to Action. J Oncol Pract 2018;14(6):335-340.

Granger BB. Science of Improvement Versus Science of Implementation: Integrating Both Into Clinical Inquiry. AACN Adv Crit Care 2018;29(2):208-212.

Granger BB, Pokorney SD, Taft C. Blending Quality Improvement and Research Methods for Implementation Science, Part III: Analysis of the Effectiveness of Implementation. AACN Adv Crit Care 2016;27(1):103-110.

Pokorney SD, Taft C, Granger BB. Blending Quality Improvement and Research Methods for Implementation Science, Part II: Analysis of the Quality of Implementation. AACN Adv Crit Care 2015;26(4):366-371.

Check DK, Zullig LL, Davis MM, et al. Quality Improvement and Implementation Science in Cancer Care: Identifying Areas of Synergy and Opportunities for Further Integration. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2019;37(27_suppl):29-29.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. History of PBRNs. https://pbrn.ahrq.gov/about/history-pbrns. Published N.D. Accessed July 26, 2019.

Nutting PA, Beasley JW, Werner JJ. Practice-based research networks answer primary care questions. JAMA. 1999;281(8):686-688.

Niebauer L, Nutting PA. Primary care practice-based research networks active in North America. J Fam Pract 1994;38(4):425-426.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. PBRN Registry. https://pbrn.ahrq.gov/pbrn-registry. Published N.D. Accessed July 26, 2019.

Davis MM, Keller S, DeVoe JE, Cohen DJ. Characteristics and lessons learned from practice-based research networks (PBRNs) in the United States. J Healthcare Leader 2012;4:107-116.

Mold JW, Peterson KA. Primary care practice-based research networks: working at the interface between research and quality improvement. Ann Fam Med 2005;3 Suppl 1:S12-20.

Green LA, Hickner J. A Short History of Primary Care Practice-based Research Networks: From Concept to Essential Research Laboratories. J Am Board Family Med 2006;19(1):1.

Green LW. Making research relevant: if it is an evidence-based practice, where’s the practice-based evidence? Fam Pract. 2008;25(suppl_1):i20-i24.

Oregon Rural Practice-based Research Network (ORPRN). About the Oregon Rural Practice-based Research Network. https://www.ohsu.edu/oregon-rural-practice-based-research-network/about. Published 2019. Accessed August 28, 2019.

Higgins J, Green S. Chochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration. http://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/. Published 2011. Accessed.

Fagnan LJ, Morris C, Shipman SA, Holub J, King A, Angier H. Characterizing a Practice-based Research Network: Oregon Rural Practice-based Research Network (ORPRN) Survey Tools. J Am Board Family Med 2007;20(2):204.

Nagykaldi Z, Mold JW, Aspy CB. Practice facilitators: a review of the literature. Fam Med 2005;37(8):581-588.

Nagykaldi Z, Mold JW, Robinson A, Niebauer L, Ford A. Practice facilitators and practice-based research networks. J Am Board Fam Med 2006;19(5):506-510.

Oregon Primary Care Association. Oregon’s Community Health Centers. https://www.orpca.org/chc/find-a-chc. Published n.d. Accessed August 30, 2019.

WWAMI Rural Health Research Center. RUCA (Rural Urban Communting Area) Data. https://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca-download.php. Published n.d. Accessed August 8, 2018.

Oregon Office of Rural Health. About Rural and Frontier Data. https://www.ohsu.edu/oregon-office-of-rural-health/about-rural-frontier/data. Published n.d. Accessed August 8, 2018.

Carey TS, Halladay JR, Donahue KE, Cykert S. Practice-based Research Networks (PBRNs) in the Era of Integrated Delivery Systems. J Am Board Fam Med 2015;28(5):658-662.

Taylor EF, Machta RM, Meyers DS, Genevro J, Peikes DN. Enhancing the primary care team to provide redesigned care: the roles of practice facilitators and care managers. Ann Fam Med 2013;11(1):80-83.

Hickner J, Green LA. Practice-based Research Networks (PBRNs) in the United States: Growing and Still Going After All These Years. J Am Board Family Med 2015;28(5):541.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Practice-based Research Networks: Application of the PBRN Model to non-Primary Care Settings - Tools, Resources, and Evidence. 2015. AHRQ Pub. No. 15-0057-5-EF. https://pbrn.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/docs/page/Affiliates.pdf. Accessed April 6, 2021.

Westfall JM, VanVorst RF, Main DS, Herbert C. Community-Based Participatory Research in Practice-Based Research Networks. Ann Family Med 2006;4(1):8-14.

Fagnan LJ, Simpson MJ, Daly JM, et al. Adapting Boot Camp Translation Methods to Engage Clinician/Patient Research Teams Within Practice-Based Research Networks: A Report From the INSTTEPP Trial and Meta-LARC Consortium. J Patient-Centered Res Rev 2018;5(4):298-303.

Daly JM, Harrod TW, Judge K, et al. Practice-Based Research Networks Ceding to a Single Institutional Review Board: A Report From the INSTTEPP Trial and Meta-LARC Consortium. J Patient-Centered Res Rev 2018;5(4):304-310.

Hartung DM, Guise J-M, Fagnan LJ, Davis MM, Stange KC. Role of practice-based research networks in comparative effectiveness research. J Comp Eff Res 2012;1(1):45-55.

Heintzman J, Gold R, Krist A, Crosson J, Likumahuwa S, DeVoe JE. Practice-based research networks (PBRNs) are promising laboratories for conducting dissemination and implementation research. J Am Board Fam Med 2014;27(6):759-762.

Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI). http://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guideelines/stari-statement/. Accessed August 15, 2019.

Statement and Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting (SQUIRE). http://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/squire. Accessed August 15, 2019.

Check DK, Zullig LL, Davis MM, et al. Improvement Science and Implementation Science in Cancer Care: Identifying Areas of Synergy and Opportunities for Further Integration. JGIM. 2020.

Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci 2015;10(1):53.

Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci 2015;10(1):21.

Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Matthieu MM, et al. Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Implement Sci 2015;10(1):109.

Vidal L-A, Marle F, Bocquet J-C. Measuring project complexity using the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Int J Proj Manag 2011;29(6):718-727.

Seers K. What is a qualitative synthesis? Evid Based Nurs 2012;15(4):101-101.

Harden S. RE-AIM. http://www.re-aim.org/. Published 2002. Accessed April 8, 2020.

Solberg LI. Improving medical practice: a conceptual framework. Ann Fam Med 2007;5(3):251-256.

Improving Chronic Illness Care. The Chronic Care Model. Group Health Research Institute. http://www.improvingchroniccare.org/index.php?p=The_Chronic_Care_Model&s=2. Published 2019. Accessed August 30, 2019.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009;4(1):50.

Mitchell SA, Chambers DA. Leveraging Implementation Science to Improve Cancer Care Delivery and Patient Outcomes. J Oncol Pract 2017;13(8):523-529.

Balasubramanian BA, Cohen DJ, Davis MM, et al. Learning Evaluation: blending quality improvement and implementation research methods to study healthcare innovations. Implement Sci 2015;10(1):31.

Glasgow RE. What Does It Mean to Be Pragmatic? Pragmatic Methods, Measures, and Models to Facilitate Research Translation. Health Educ Behav 2013;40(3):257-265.

Ramanadhan S, Davis MM, Armstrong R, et al. Participatory implementation science to increase the impact of evidence-based cancer prevention and control. Cancer Causes Control 2018;29(3):363-369.

Wheeler SB, Davis MM. “Taking the Bull by the Horns”: Four Principles to Align Public Health, Primary Care, and Community Efforts to Improve Rural Cancer Control. J Rural Health 2017;33(4):345-349.

Baskerville NB, Liddy C, Hogg W. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Practice Facilitation Within Primary Care Settings. Ann Family Med 2012;10(1):63-74.

Mader EM, Fox CH, Epling JW, et al. A Practice Facilitation and Academic Detailing Intervention Can Improve Cancer Screening Rates in Primary Care Safety Net Clinics. J Am Board Family Med 2016;29(5):533.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Practice Facilitation. https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/practice-facilitation. Published N.D. Accessed July 26, 2019.

Davis MM, Howk S, Spurlock M, McGinnis PB, Cohen DJ, Fagnan LJ. A qualitative study of clinic and community member perspectives on intervention toolkits: “Unless the toolkit is used it won’t help solve the problem”. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17(1):497.

Ritchie MJ DK, Miller CJ, Oliver KA, Smith JL, Lindsay JA, Kirchner JE. Using Implementation Facilitation to Improve Care in the Veterans Health Administration (Version 2). . Veterans Health Administration, Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) for Team-Based Behavioral Health 2017.

Harvey G, Kitson A. PARIHS revisited: from heuristic to integrated framework for the successful implementation of knowledge into practice. Implement Sci 2016;11(1):33.

Lewis CC, Boyd MR, Walsh-Bailey C, et al. A systematic review of empirical studies examining mechanisms of implementation in health. Implement Sci 2020;15(1):21.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the staff at ORPRN and the clinics that have made this work possible over the past two decades.

Funding

Preparation of this manuscript was partially funded through a patient-centered outcomes research award from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R18HS027080). Dr. Davis’ time is supported in part by a career development award from the National Cancer Institute (1K07CA211971).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations

This paper has not been presented elsewhere.

Appendix 1

ESM 1

(DOCX 493 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Davis, M.M., Gunn, R., Kenzie, E. et al. Integration of Improvement and Implementation Science in Practice-Based Research Networks: a Longitudinal, Comparative Case Study. J GEN INTERN MED 36, 1503–1513 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06610-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06610-1