ABSTRACT

Background

eConsult programs have been instituted to increase access to specialty expertise. Opt-in choice eConsult programs maintain primary care physician (PCP) autonomy to decide whether to utilize eConsults versus traditional specialty referrals, but little is known about how this intervention may impact PCP eConsult adoption and traditional referral demand.

Objective

We assessed the feasibility of implementing an opt-in choice eConsult program and examined whether this intervention reduces demand for in-person visits for primary care patients requiring specialty expertise.

Design

Stepped-wedge, cluster randomized trial conducted from July 2018 to June 2019.

Participants

Sixteen primary care practices in a large, urban academic health care system.

Intervention

Our intervention was an opt-in choice eConsult available in addition to traditional specialty referral; our implementation strategy included in-person training, audit and feedback, and incentive payments.

Main measures

Our implementation outcome measure was the eConsult rate: weekly proportion of eConsults per PCP visit at each site. Our intervention outcome measure was traditional referral rate: weekly proportion of referrals per PCP visit at each site. We also assessed PCP experiences with questionnaires.

Key results

Of 305,915 in-person PCP visits, there were 31,510 traditional referrals to specialties participating in the eConsult program, and 679 eConsults. All but one primary care site utilized the opt-in choice eConsult program, with a weekly rate of 0.05 eConsults per 100 PCP visits by the end of the study period. The weekly rate of traditional referrals was 11 per 100 PCP visits at the end of the study period; this represents a significant increase in traditional referral rate after implementation of eConsults. PCPs were generally satisfied with the eConsult program and valued prompt provider-to-provider communication.

Conclusions

Implementation of an opt-in choice eConsult program resulted in widespread PCP adoption; however, this did not decrease the demand for traditional referrals. Future studies should evaluate different strategies to incentivize and increase eConsult utilization while maintaining PCP choice.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Health care systems face a mismatch between supply and demand for specialty care, resulting in inadequate access to specialty expertise. To increase specialty access, institutions may implement eConsult programs: asynchronous, provider-to-provider communication that addresses patient care and may eliminate need for in-person visits.1 Health system-based eConsult programs have been instituted using two models2, 3: (1) integrated into default referral processes, with all primary care physicians’ (PCPs) requests initiated through eConsults and specialists determining whether in-person visits are required, or (2) opt-in choice of eConsult in addition to traditional referrals.

These two different eConsult models can be examined using insights from behavioral economics,4 as they employ different choice architecture to influence utilization of referrals and in-person visits. The choice architecture of an intervention (e.g., presence of a default, opt-in or opt-out, limiting choice) can impact decision-making. Integrated eConsult programs restrict PCP choice and shift in-person visit decision-making to specialists; opt-in choice eConsult programs allow PCPs to request eConsults instead of traditional referrals, maintaining PCP autonomy for in-person visit decision-making. Health care systems with integrated eConsult programs have seen reductions in demand for in-person visits and subsequent reductions in wait time for specialty care.1, 5, 6 Systems that have instituted opt-in choice eConsult programs have reported that varying proportions of eConsults do not require in-person visits (12–84%),7 but little is known about PCP adoption of opt-in choice eConsults or about how this strategy impacts demand for traditional referrals.8

Early adopters have described the design of eConsult programs focusing on format of eConsults, workflows, and compensation; however, there are limited reports of the development and implementation of system-specific eConsult programs.9, 10 In addition to intervention choice architecture, different implementation strategies, such as customizing an intervention to fit local needs, promotion of the intervention, incentives, and feedback, can influence PCP decision-making. As eConsults are instituted across health systems, it is important to understand facilitators and barriers to successful implementation.

The aim of our initiative was to enhance access to specialty expertise by implementing an opt-in choice eConsult program within a large, urban, academic health care system. Our study evaluated the feasibility of implementing an opt-in choice eConsult program and assessed whether introduction of the intervention reduced demand for in-person visits for PCPs requiring specialty expertise.

METHODS

Setting and participants

This study occurred from July 2018 through June 2019 at Montefiore Medical Center, an academic medical center in Bronx, NY. The system provides primary and specialty care in a network of outpatient practices with over three million visits annually. Primary care practices include teaching sites which are Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) or FQHC Look-Alikes, including medical trainees and have attending physicians with academic appointments; neighborhood sites which are FQHCs without trainees; and group practices without trainees. Most patients (approximately 75%) are publicly insured by Medicaid and/or Medicare. The system uses Epic electronic medical record (EMR) software. This study was approved by the Montefiore/Albert Einstein Institutional Review Board.

Study design

We assessed our opt-in choice eConsult program using a stepped-wedge, cluster randomized design (Fig. 1). Sixteen internal medicine and family medicine practices were classified (teaching site, neighborhood site, group practice) and then included in one of three clusters using stratified random sampling with practice type as the stratifying variable. We chose to scale our intervention using a stepped-wedge cluster randomized design to (1) quantify demand for eConsults over time to inform training needs for each eConsult specialty; (2) provide on-site training for each primary care practice during standing meetings; (3) evaluate the effect of our program on outcomes (defined below).

Implementation

Our opt-in choice eConsult program was designed by an interdisciplinary team after reviewing existing eConsult programs and the framework for establishing an e-consultation service described by Liddy et al.1, 9,10,11,12,13 The eConsult team was directed by a PCP (SR) with expertise in quality improvement and included physician champions from primary care (JA, JD), specialty care (YT, EE), medical informatics (MB), administrators, and referral coordinators. A pilot program was first tested at three primary care practices; the pilot practices were not included in this study. The pilot program was supported by the Department of Medicine and program expansion was supported by the Medicaid Delivery System Reform Incentive Payments (DSRIP) program.

Primary care implementation

A focus group was held with PCPs from five sites during a monthly PCP meeting. The focus group was facilitated by the eConsult director (SR) and an observer recorded participants’ responses on a whiteboard. The facilitator asked: (1) What are barriers to specialty care? (2) What is an ideal workflow for an eConsult program? (3) What concerns do you have with an eConsult program? The eConsult team reviewed responses using thematic analysis, identifying the following areas for improvement which informed the intervention: (1) lack of a triage system for urgent in-person visits led to development of appointment scheduling structure following an eConsult, (2) concern that patient care responsibilities would be shifted from specialists to PCPs and that appointment decision-making autonomy would be lost led to an opt-in choice eConsult model, (3) concern about quality of specialist eConsult recommendations led to use of audit and feedback for eConsultant recommendations.

PCPs at each primary care practice received an in-person introduction to the program during monthly practice meetings prior to local site implementation. These 30-min training sessions were led by the eConsult program director (SR) and framed as a quality improvement initiative for access to specialty expertise. The sessions included background on problems identified by PCPs, the eConsult workflow, and a request for ongoing feedback to improve the program. Outcomes were reviewed at quarterly meetings with medical directors and administrative leaders. Additionally, PCPs received compensation corresponding to 0.25 wRVU per completed eConsult.

All eConsults were reviewed weekly by the eConsult team for audit and feedback. The eConsult director (SR) e-mailed PCPs to discuss the following: quality of questions (e.g., omission of specific questions or requesting appointment only), incomplete workflows, and feedback for ambiguous eConsult recommendations.

Specialty implementation

We identified specialties (endocrinology, hematology, gastroenterology, rheumatology) with the greatest need for improvement based on wait times and perceptions that many consult questions could be answered without an in-person visit. eConsultants were selected based on interest in participating. Initially, one eConsultant was identified per specialty, with additional eConsultants recruited as demand grew. Each specialty designed their own workflow to schedule patients requiring expedited appointments, often overbooking appointment slots.

Each eConsultant received an in-person introduction to the program prior to formal participation, including background on program goals, workflow training, and opportunity to ask questions and provide suggestions. These 60-min sessions were led by the program director (SR) for the first group of eConsultants. New eConsultants were subsequently trained by their same-specialty colleagues. eConsultants received compensation corresponding to 0.5 wRVU per completed eConsult. eConsultants participated in monthly meetings with the eConsult team to review and improve outcomes, quality of eConsult communication, and workflow. The program director (SR) also communicated with eConsultants through e-mail as part of the weekly audit and feedback process.

Intervention

Our intervention was our opt-in choice eConsult program. To place an eConsult order, an EMR-based workflow was designed in which the PCP completes two free-text prompts:

-

“Please provide a brief summary of the patient:”

-

“Please provide your questions for the eConsultant:”

The order was directed to the specialty eConsultant who was expected to respond within three business days with free text:

-

“Assessment and recommendations:”

-

“Types of recommendations provided (Select all that apply): Tests, Treatments, Expedited appointment, Regular appointment, Procedure, Alternate specialty recommended, No further evaluation needed by this specialty, More information needed prior to recommendation.”

The “types of recommendations provided” section allowed the eConsult team to track and review outcomes. The recommendation was sent back to the PCP with opportunity for iterative communication or to acknowledge next steps. The eConsult communication was available in the EMR as part of a patient’s chart. Resident physicians could place eConsult orders under supervision of attending physicians.

PCPs could continue to use traditional referrals for specialty in-person appointments throughout the study. In this workflow, a PCP ordered an electronic referral after which either the patient or referral coordinator scheduled the appointment. This process was variable between practices and specialties. If a timely appointment was not available, the PCP often called to request an expedited appointment. The traditional referral did not require a specific consult question. Following an in-person appointment, the progress note was forwarded to the referring PCP; however, there was no direct communication between the PCP and specialist.

Measures

To evaluate the implementation of our opt-in choice eConsult program, we measured the eConsult rate: weekly proportion of eConsults per primary care visit at each site. To evaluate our intervention’s impact on demand for traditional referrals, we measured traditional referral rate: weekly proportion of referrals per primary care visit at each site. Visit, referral and eConsult data were obtained from the EMR. Referral data were restricted to new patient requests (no visit in the last 18 months) for eConsult-participating specialties. To assess barriers and facilitators to implementation, we conducted Web-based quarterly surveys of PCP experiences with eConsults and traditional referrals.

Analysis

Primary care practice characteristics (frequency of visits, referrals, and eConsults) were examined using descriptive statistics. Weekly proportions of referrals and eConsults were examined using a statistical process control p-chart. A linear mixed model (model 1) was constructed to evaluate whether the weekly eConsult rate differed by practice type (teaching, neighborhood, or group), adjusted for cluster and concurrent traditional referral rate. Linear mixed models (models 2A and 2B) were constructed to evaluate whether traditional referral rate at each practice site decreased after implementation of the intervention (eConsult available: no or yes), adjusted for practice type (teaching, neighborhood, or group) and cluster. In model 2B, we examined whether the practice type modified the traditional referral rate after implementation of the intervention (interaction variable for eConsult available and practice type). In all models, to account for within-site correlations over time, the covariance matrix of the error term was assumed to be a full Toeplitz matrix, which can be viewed as an autoregressive structure.

RESULTS

During the 12-month study period, PCPs at the 16 practices completed 305,915 in-person visits, placed 31,510 traditional referrals to specialties participating in the opt-in choice eConsult program, and placed 679 eConsults. Table 1 shows primary care practice characteristics by week before and after implementation of our intervention. All eConsults were answered within three business days (mean < 1 day). Most eConsults (61%) resulted in recommendation without need for in-person appointments, while 24% recommended traditional appointments and 15% recommended expedited appointments.

Implementation

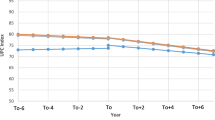

All sites but one utilized the opt-in choice eConsult program (Table 1). The mean weekly rate of eConsults was 0 per 100 PCP visits prior to implementation (weeks 1–13) and 0.5 per 100 PCP visits after implementation of the intervention at all sites (weeks 40–52) (Fig. 2). The weekly eConsult rate differed by practice type (controlling for concurrent referral rate and cluster): on average, the weekly rate of eConsults in teaching practices was 1.005 eConsults per 100 PCP visits for every one eConsult per 100 PCP visits at group practices (Table 2, model 1: p < 0.001); neighborhood practices had similar eConsult adoption to group practices (Table 2, model 1: p = 0.51). On average, the weekly rate of eConsult use increased by 0.03 per 100 PCP visits for every one traditional referral per 100 PCP visits (Table 2, model 1: p < 0.001).

Intervention

The average weekly rate of traditional referrals was 10 per 100 PCP visits prior to implementation (weeks 1–13) and 11 per 100 PCP visits after implementation at all sites (weeks 40–52) (Fig. 2). The average weekly rate of traditional referrals increased by 1.005 per 100 PCP visits after the introduction of eConsults, controlling for site type and cluster (Table 3, model 2A: p = 0.002).

There was an interaction between practice site type and eConsult availability (Table 3, model 2B: coefficient for eConsult availability with group practice as reference, p < 0.001). After implementation of eConsults, group practices’ average weekly rate of traditional referrals increased by 1.01 per 100 PCP visits; this increase was similar in neighborhood practices (Table 3, model 2B: coefficient for neighborhood practice and eConsult availability, p = 0.18). However, in teaching practices, the average weekly rate of traditional referrals was 0.01 lower per 100 PCP visits compared with group practices, indicating no net change in referral rate after eConsult availability (Table 3, model 2B: coefficient for teaching practice and eConsult availability, p = 0.02). Over the entire study period, the average rate of referrals was lower at teaching practices compared with group practices (Table 3, model 2B: coefficient for teaching versus group practices = − 0.05, p = 0.01); there was no difference between rates of traditional referral for neighborhood practices versus group practices (Table 3, model 2B: coefficient for neighborhood versus group practices = − 0.03, p = 0.16).

Primary care physician experiences

Response rate to the quarterly questionnaires was 37%, 32%, and 21% over three administrations. A majority of PCPs were “very satisfied” with eConsults versus “somewhat satisfied, neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, somewhat dissatisfied, very dissatisfied” (82%, 80%, 69% over the three questionnaires). The reported average time to complete an eConsult and associated follow-up (such as communicating with patients and ordering studies) decreased over the study period, with 44% responding < 10 min, 41% 10–19 min, 6% 20–29 min, and 9% 30+ min during the last questionnaire administration. Both positive and negative themes emerged from the request for “comments, questions or concerns.” Positive feedback included timeliness of eConsult responses, avoidance of additional appointments for patients, enjoyment of intellectual discussions with colleagues, facilitation of expedited appointments, and request for additional participating specialties. Negative feedback included request to review eConsult workflow and available specialties, burden of additional responsibilities without adequate time and/or compensation, consistent quality between eConsultant recommendations, and need to improve timeliness of traditional referrals.

DISCUSSION

The Montefiore eConsult program was designed as an opt-in choice in addition to traditional specialty referrals. Following an implementation strategy which included in-person training, audit and feedback, and incentive payments, all primary care practices but one adopted eConsults. Use of eConsults was different among practice types, with teaching sites more likely to utilize eConsults than both FQHC and non-FQHC sites without trainees. The impact of eConsults on referral rates was also different among practice types. Unexpectedly, we found that teaching sites had no change in referrals after implementation of eConsults, while the other two practice site types had an increase in traditional referrals. PCPs were generally satisfied with eConsults and valued prompt communication. Barriers to eConsult utilization included time constraints and added responsibilities.

Interpretation

Successful implementation of an opt-in choice eConsult program at our institution was facilitated by leadership sponsorship, participation of PCP and specialist champions in the development process, and customization to local needs. These are elements of success described by other leaders of eConsult programs.10 We learned that the local context of practice setting (teaching or non-teaching sites) influences both utilization of eConsults and impact of eConsults on traditional referral demand. For example, the educational aspect of eConsults (which has been reported by others14, 15) may be valued more at teaching practices, influencing utilization. It is possible that other unmeasured variations between teaching and non-teaching sites (such as PCP workload, assistance with referral scheduling, and pre-existing relationships with specialists) impact adoption of eConsults. Future qualitative research is needed to investigate how these factors influence eConsult outcomes.

This is one of two known studies investigating how an opt-in choice eConsult program impacts demand for traditional referrals. In contrast to our study, Gleason et al. described a 19% reduction in referral rate following introduction of eConsults.8 While both studies saw adoption of eConsults across sites and providers, differences in observed referral patterns may be related to the selection of participating eConsult specialties. In future studies, we will assess how differences between specialties affect PCP adoption of eConsults and eConsultant recommendations. Another explanation for different findings is that our opt-in choice did not shift PCP decision-making to consider eConsults as an alternative to traditional referrals but instead induced demand for questions that might not have previously generated a traditional referral. Future studies might also test other choice structures, such as coupling the eConsult and traditional referral orders or utilizing an opt-out choice approach.

Health care systems that have instituted eConsults, as either integrated or opt-in choice programs, report PCPs’ satisfaction.13 Benefits to PCPs include educational advantages, improved access to care, and allowing PCPs to provide comprehensive care.16, 17 PCP concerns revealed during our focus group have also been reported, including shift of work from specialists to PCPs and lack of dedicated time for non-face-to-face activities.3, 13, 16,17,18 Interestingly, communication between PCPs and specialists has been described as both a benefit and disadvantage of eConsults; while many physicians appreciate this opportunity, others point out that the tone and quality of communication can also be a barrier to care. Because individual provider variations exist in effective eConsult communication, it is important to maintain careful selection and ongoing feedback for eConsultants.

Limitations

We were unable to examine how different components of our implementation strategy impacted outcomes. For example, because of delays and variable timing of payments, we could not analyze the impact of incentives on eConsult utilization. Low response to the PCP questionnaire raises the possibility of selection bias and may limit generalizability. Generalizability may also be impacted by our focus on a single system’s implementation; however, the principles of our implementation strategy are important for other institutions to consider. Lastly, we focused on demand for in-person specialty visits as our outcome; however, research into patient-oriented outcomes comparing eConsults to traditional referrals is needed to determine if positive patient-centered outcomes may also incentivize change in referral patterns.

CONCLUSIONS

This study suggests that an opt-in choice eConsult program can be implemented across a large, urban, multi-site academic institution with PCPs selectively utilizing eConsults when they determine added value to patient care while balancing time and compensation restraints. To maintain PCP autonomy and satisfaction, we implemented an opt-in system which had limited impact on demand for in-person visits. Future interventions to improve eConsult utilization should consider PCP concerns, such as time constraints and clinical effort shifted from specialists to PCPs.

REFERENCES

Chen AH, Murphy EJ, Yee HF Jr. eReferral--a new model for integrated care. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(26):2450-2453.

Tuot DS, Liddy C, Vimalananda VG, et al. Evaluating diverse electronic consultation programs with a common framework. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):814.

Gleason N, Ackerman S, Shipman SA. Econsult—transforming primary care or exacerbating clinician burnout? JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(6):790-791.

Volpp KG, Asch DA. Make the healthy choice the easy choice: using behavioral economics to advance a culture of health. QJM. 2017;110(5):271-275.

Barnett ML, Yee HF Jr, Mehrotra A, Giboney P. Los Angeles Safety-Net Program eConsult System Was Rapidly Adopted And Decreased Wait Times To See Specialists. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(3):492-499.

Rea CJ, Wenren LM, Tran KD, et al. Shared Care: Using an Electronic Consult Form to Facilitate Primary Care Provider-Specialty Care Coordination. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(7):797-804.

Liddy C, Drosinis P, Keely E. Electronic consultation systems: worldwide prevalence and their impact on patient care-a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2016;33(3):274-285.

Gleason N, Prasad PA, Ackerman S, et al. Adoption and impact of an eConsult system in a fee-for-service setting. Healthc (Amst). 2017;5(1-2):40-45.

Liddy C, Maranger J, Afkham A, Keely E. Ten steps to establishing an e-consultation service to improve access to specialist care. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19(12):982-990.

Tuot DS, Leeds K, Murphy EJ, et al. Facilitators and barriers to implementing electronic referral and/or consultation systems: a qualitative study of 16 health organizations. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):568.

Barnett ML, Mehrotra A, Frolkis JP, et al. Implementation Science Workshop: Implementation of an Electronic Referral System in a Large Academic Medical Center. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(3):343-352.

Gupte G, Vimalananda V, Simon SR, DeVito K, Clark J, Orlander JD. Disruptive Innovation: Implementation of Electronic Consultations in a Veterans Affairs Health Care System. JMIR Med Inform. 2016;4(1):e6.

Vimalananda VG, Gupte G, Seraj SM, Orlander J, Berlowitz D, Fincke BG. Electronic consultations (e-consults) to improve access to specialty care: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. J Telemed Telecare. 2015;21.

Kwok J, Olayiwola JN, Knox M, Murphy EJ, Tuot DS. Electronic consultation system demonstrates educational benefit for primary care providers. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(7):465-472.

Liddy C, Afkham A, Drosinis P, Joschko J, Keely E. Impact of and Satisfaction with a New eConsult Service: A Mixed Methods Study of Primary Care Providers. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(3):394-403.

Deeds SA, Dowdell KJ, Chew LD, Ackerman SL. Implementing an Opt-in eConsult Program at Seven Academic Medical Centers: a Qualitative Analysis of Primary Care Provider Experiences. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(8):1427-1433.

Kim Y, Chen AH, Keith E, Yee HF, Kushel MB. Not perfect, but better: primary care providers’ experiences with electronic referrals in a safety net health system. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24.

Lee MS, Ray KN, Mehrotra A, et al. Primary care practitioners’ perceptions of electronic consult systems: A qualitative analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(6):782-789.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the primary care physicians who participated in focus group sessions and specialty eConsultant physicians who participated in developing the eConsult program.

The eConsult pilot program was funded by the Montefiore Department of Medicine. Funding for the expansion of the program was supported by the Medicaid Delivery System Reform Incentive Payments (DSRIP) Innovation Fund Program. Bronx Partners for Healthy Communities established the Innovation Fund Program to encourage and promote member organizations to take on innovative and new interventions and programs to address certain gaps in care and missing links in the care support structure in and among member organizations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

SR and DL report support from Bronx Partners for Healthy Communities: Innovation Fund Program, during the conduct of the study. YT reports grants from Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF) and Pfizer, outside the submitted work. CZ, JD, EE, and JA do not report any conflicts of interest with this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rikin, S., Zhang, C., Lipsey, D. et al. Impact of an Opt-In eConsult Program on Primary Care Demand for Specialty Visits: Stepped-Wedge Cluster Randomized Implementation Study. J GEN INTERN MED 35 (Suppl 2), 832–838 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06101-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06101-9