Abstract

Background

Health risk assessments (HRAs) and healthy behavior incentives are increasingly used by state Medicaid programs to promote enrollees’ health.

Objective

To evaluate enrollee experiences with HRAs and healthy behavior engagement in the Healthy Michigan Plan (HMP), a state Medicaid expansion program.

Design

Telephone survey conducted in Michigan January–October 2016.

Participants

A random sample of HMP enrollees aged 19–64 with ≥ 12 months of enrollment, stratified by income and geographic region.

Main Measures

Self-reported completion of an HRA, reasons for completing an HRA, commitment to a healthy behavior, and choice of healthy behavior.

Key Results

Among respondents (N = 4090), 49.3% (95% CI 47.3–51.2%) reported completing an HRA; among those with a primary care provider (PCP) (n = 3851), 85.2% (95% CI 83.5–86.7%) reported visiting their PCP during the last 12 months. Most enrollees having a recent PCP visit reported discussing healthy behaviors with them (91.1%, 95% CI 89.6–92.3%) and were more likely to have completed an HRA than enrollees without a recent PCP visit (52.7%, 95% CI 50.5–52.8% vs. 36.2%, 95% CI 31.7–41.1%; p < 0.01). Among enrollees completing an HRA, nearly half said they did it because their PCP suggested it (45.9%, 95% CI 43.2–48.7%), and most reported it helped their PCP understand their health needs (89.7%). Awareness of financial incentives was limited (28.1%, 95% CI 26.3–30.0%), and very few reported it as the primary reason for HRA completion (2.5%, 95% CI 1.8–3.4%). Most committed to a healthy behavior (80.7%, 95% CI 78.5–82.8%), and common behaviors chosen were nutrition/diet (57.2%, 95% CI 54.2–60.2%) and exercise/activity (52.6%, 95% CI 49.5–55.7%).

Conclusions

In the Healthy Michigan Plan, PCPs appeared influential in enrollees’ completion of HRAs and healthy behavior engagement, while knowledge of financial incentives was limited. Additional study is needed to understand the relative importance of financial incentives and PCP engagement in impacting healthy behaviors in state Medicaid programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

In April 2014, Michigan expanded Medicaid to all eligible non-elderly adults under the Affordable Care Act (ACA).1 Under Republican control, it implemented the program—the Healthy Michigan Plan (HMP)—under a Section 1115 Medicaid demonstration waiver with a set of unique state program features.2,3,4 Enrollees were expected to see a primary care provider (PCP) within 3 months of enrollment, and financial incentives were developed to encourage enrollees to complete a state-specified health risk assessment (HRA) and commit to a healthy behavior after consultation with their PCPs.

To date, the expectation that enrollees complete an HRA following enrollment has been implemented as a feature of Medicaid plans in only three states (Indiana, Iowa, and Michigan).5 Similar to Iowa and Indiana plans, Michigan required cost-sharing (as co-pays) for all enrollees and monthly contributions for enrollees with incomes of 100–133% of the federal poverty level. All incorporated financial incentives of similar magnitude (through reduced cost-sharing or a gift card) for completing an HRA5, 6; and Iowa’s plan, like Michigan’s, issued guidance to enrollees to see their PCP within 12 months. A key difference, however, is that successful HRA completion in Michigan required an encounter with a health care provider. In October 2015, this feature became tied to quality improvement payments for Medicaid managed care plans responsible for HMP enrollees.4, 7 HRAs must be completed by the enrollee, attested by the provider, and submitted to the state Medicaid program to be considered “complete” by the state.

While states have introduced healthy behavior financial incentives for Medicaid enrollees prior to the ACA,8 effects of these programs on cost and morbidity have been mixed.9,10,11 In experimental settings, financial incentives for smoking cessation, primary care visits, and physical activity have had encouraging results12,13,14,15; however, for large-scale implementation, establishing awareness of incentives and creating and maintaining reliable data management systems present challenges. Low participation rates—both for HRA completion and for healthy behavior engagement—were observed in Iowa’s plan 1 year after implementation, and Michigan has subsequently taken steps to refine its HRA form and completion process.16, 17 Healthy behaviors, such as diet and exercise, are especially beneficial effects for those at risk for or diagnosed with chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease or diabetes.18,19,20 Whether incentivized healthy behavior Medicaid programs, such as HMP, lead to engagement among those with chronic illness is not well studied.

Prior work has shown that a majority of Michigan PCPs reported HMP had a positive impact on health behaviors just 1 year following program adoption.21 However, HMP enrollees’ engagement related to HRAs has not previously been reported. We sought to assess HMP enrollees’ level of engagement with HRAs and commitment to healthy behaviors following adoption of HMP and whether those with chronic illness responded differently.

METHODS

Study Setting

The Healthy Michigan Voices (HMV) Survey was developed as part of a Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) contract to evaluate HMP.3, 22 An important focus of the survey was to gain insights and perspectives about HMP enrollees’ experiences with PCP visits and HRA completion. While HRA policies in HMP have changed over time, no significant changes occurred during the study period. However, some survey responses may have applied to the time period prior to policy adjustments, such as quality improvement payments to managed care plans that started in October 2015. As a federally mandated evaluation of a government health program, the study was deemed exempt from review by the University of Michigan and MDHHS institutional review boards.

Survey Sampling

A random sample of HMP enrollees was selected monthly for a telephone survey in January–October 2016, based on previously validated survey designs.23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32 Sampling was stratified by income and state region, as previously described.3 Enrollees were included if they were ages 19–64, and had been enrolled in HMP for ≥ 12 months—nine of which in an HMP managed care plan. Additional inclusion criteria included preferred language of English, Spanish, or Arabic, and a complete Michigan address and working telephone number. Respondents were given a $25 gift card for completing the survey.

Data Collection and Analysis

A total of 9227 eligible HMP enrollees were mailed a letter and brochure describing the project prior to receiving a telephone call. Of those, 4108 enrollees completed the survey (weighted response rate = 53.7% using the American Association for Public Opinion Research’s response rate formula 3).33, 34 Eighteen surveys with > 20% missing data were excluded from analysis, and the remaining 4090 were included in the analytic sample. Enrollees who were younger, male, or living in Detroit were slightly less likely to respond to the survey (see Appendix Table A1). Income was not associated with nonresponse. To account for potential nonresponse bias, we applied nonresponse adjustment to sampling weights in which we controlled for age, gender, race/ethnicity, enrollment month, sampling strata, sampling month, and the interaction between sampling strata and sampling month.

Measures

Descriptive statistics were weighted for selection, non-working numbers, unknown eligibility, and nonresponse. Primary outcomes included whether enrollees reported completing an HRA, reasons enrollees completed an HRA, whether enrollees completing an HRA committed to work on ≥ 1 healthy behavior, which healthy behaviors were chosen, and reasons for choosing to work on a specific healthy behavior. Respondents who reported completing the HRA were also asked to report their level of agreement with the statements, “I think doing the health risk assessment was valuable for me to improve my health,” “I think doing the Health Risk Assessment was helpful for my primary care provider to understand my health needs,” and “I know what I need to do to be healthy, so the Health Risk Assessment wasn’t that helpful.” Other measures included whether the enrollee had an established PCP and whether the enrollee had seen the PCP within 12 months.

Analysis

Bivariate statistics for yes/no responses were used to compare HRA completion rates by recent PCP visit status, reasons for completing an HRA, and choice of healthy behavior. For survey responses that expressed level of agreement, a positive response was classified as “agree” or “strongly agree.” Subgroup analyses were performed among respondents with ≥ 1 of 4 claims-based chronic disease diagnosis (asthma, cardiovascular disease, COPD, and diabetes) as defined by the 2016 Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS).35

RESULTS

Enrollee Characteristics

Of the 4090 respondents, 26% (95% CI 24.5–27.6%) were ages 51–64, 61.2% were White (95% CI 59.3–63.0%), 26.1% were Black (95% CI 24.3–27.9%), 5.2% were Hispanic/Latino (95% CI 4.4–6.2%), and 6.2% were Arab, Chaldean, or Middle Eastern (95% CI 5.3–7.2%). Nearly half were employed (48.8%, 95% CI 47.0–50.7%), and half (51.8%, 95% CI 50.9–52.8%) had very low income (0–35% of the federal poverty level). One-quarter had at least one chronic disease (25.1%, 95% CI 23.5–26.8%). Respondents with at least one chronic disease were significantly less likely than respondents without chronic disease to be employed (39.0%, 95% CI 35.7–42.5% vs. 52.1%, 95% CI 49.9–54.4%) and significantly more likely to be older (43.1%, 95% CI 39.7–46.5% vs. 20.3%, 95% CI 18.8–22.0%), and have very low income (56.2%, 95% CI 53.2–59.2% vs. 50.4%, 95% CI 48.7–52.0%) (see Table 1).

PCP Visits and HRA Completion

49.3% of enrollees (95% CI 47.3–51.2%) reported completing an HRA, and among those who reported having a PCP (n = 3851), 85.2% (95% CI 83.5–86.7%) reported having a PCP visit during the last 12 months. Respondents were significantly more likely to report completing an HRA if they had seen their PCP within 12 months than if they had not (52.7%, 95% CI 50.5–52.8% vs. 36.2%, 95% CI 31.7–41.1%; p < 0.01) (see Table 1; Fig. 1). Among respondents who reported having a visit with their PCP within 12 months (n = 3386), 91.1% (95% CI 89.6–92.3%) said they had talked with their PCP about things they can do to be healthy and prevent medical problems; respondents with a chronic disease were significantly more likely to have done so than those without (94.7%, 95% CI 92.6–96.2%, p < 0.01).

Reasons for HRA Completion

The most common reason enrollees reported for completing an HRA (n = 2102) was that their PCP suggested it (45.9%, 95% CI 43.2–48.7%) (Fig. 2). Other reasons for HRA completion reported by enrollees included getting it in the mail (33.0%, 95% CI 30.4–35.6%) and completing the HRA during enrollment over the phone (12.6%, 95% CI 10.9–14.6%). The majority of respondents who completed an HRA either after receipt in the mail or by phone at enrollment reported taking the form to their PCP (71.9%, 95% CI 66.5–76.7).

Among enrollees who reported completing an HRA (n = 2102), a majority (83.7%) reported that completing an HRA was valuable for them to improve their health, while 89.7% reported that doing an HRA was helpful for their PCP to understand their health needs. Only 31.5% reported that completing the HRA was not that helpful because they know what they need to do to stay healthy.

Enrollees were unlikely to report financial incentives as a motivator for HRA completion: only 2.5% (95% CI 1.8–3.4%) reported the reason was to receive a gift card, money, or reward; and only 0.1% (95% CI 0.0–0.3%) said they did it to save money on co-pays and cost-sharing. Similarly, rewards were not a motivator for healthy behaviors: less than half (40.6%) agreed or strongly agreed that information about healthy behavior rewards had led them to do something they might not have done otherwise. However, it is important to note that knowledge and awareness of financial incentives for HRA completion were limited: only 28.1% (95% CI 26.3–30.0%) said they might get a reduction in the amount they have to pay if they completed an HRA.

Commitment to Healthy Behaviors

Among respondents who reported completing an HRA (n = 2102), 80.7% (95% CI 78.5–82.8%) chose to work on a healthy behavior or do something good for their health; compared with the full sample, those with chronic diseases were significantly more likely to do so (87.6%, 95% CI 83.9–90.5%, p < 0.01) (Fig. 3).

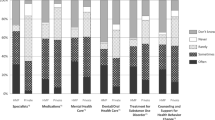

The most common health behaviors respondents reported choosing were nutrition and diet (57.2%, 95% CI 54.2–60.2%) and exercise and activity (52.6%, 95% CI 49.5–55.7%) (Fig. 4). Smoking cessation was chosen among 18.4% (95% CI 16.2–20.9%) of all respondents who chose a health behavior. Those with a mental health condition or substance use disorder were more likely than enrollees without these conditions to choose smoking cessation (24.9%, 95% CI 21.4–28.9% vs. 12.2%, 95% CI 9.7–15.3%; p < 0.01) and to quit or reduce alcohol consumption (6.2%, 95% CI 4.3–8.9% vs. 0.8%, 95% CI 0.4–1.6%; p < 0.01). There was also a trend toward enrollees with mental health or substance use disorders selecting treatment for substance use disorder in the HRA (0.3%, CI 0.1–1.0% vs. 0.0%; p = 0.09). Enrollees rarely reported selecting preventive services such as flu vaccines (0.9%, 95% CI 0.5–1.4%). Chronic disease management was rarely selected but more likely among enrollees with chronic disease than those without, including taking medicines regularly (3.4%, 95% CI 1.6–7.0% vs. 1.8%, 95% CI 1.1–3.1%) and monitoring blood pressure and blood sugar (2.9%, CI 1.6–5.0% vs. 1.0%, 95% CI 0.6–1.7%).

Among those who chose to work on a health behavior (n = 1690), 61.3% (95% CI 58.2–64.4%) of the full sample and 71.8% (95% CI 66.9–76.3%) of those with chronic disease said their PCP or health plan helped them work on their behavior, whereas only 8.0% (95% CI 6.6–9.7%) of all and 9.5% (95% CI 6.9–13.1%) of those with chronic disease said there was help they wanted but did not get.

DISCUSSION

Implementation of HMP was associated with high levels of self-reported HRA completion and commitment to healthy behaviors, with nearly half of all enrollees reporting having completed an HRA. Primary care provider involvement was correlated with all stages of HRA completion and healthy behavior engagement, including HRA completion rate, reasons for completing an HRA, and whether an enrollee chose to work on a health behavior.

Three important findings emerged from this study. First, self-report of HRA completion was substantial and comprised nearly half of all HMP enrollees. Claims data in other states have documented much lower levels of HRA completion. Certain features of HMP may have been more effective in engaging enrollees to complete HRAs and commit to healthy behaviors; however, additional study is needed to explore the relationship between completion rates by claim and self-report and potential drivers for any existing differences.

A second and related finding is the apparent influence of health care providers on health risk assessment and healthy behaviors. The high correlation between HRA completion and having a PCP visit within 12 months was an intended consequence of HMP; however, the most common reason enrollees gave for HRA completion was that their PCP had suggested it, suggesting a PCP-specific influence in addition to the requirement to see a PCP for HRA submission. Nearly all enrollees who saw their PCP within 12 months reported their PCP had discussed healthy behaviors with them, and nearly all who completed an HRA felt it was valuable for their provider to better understand their health needs. Ultimately, approximately 80% who reported completing an HRA elected to work on at least one health behavior.

The value enrollees place on interactions and counseling with their PCPs is significant. National strategies to prevent and improve chronic disease burden have focused on structural and environmental approaches to promoting healthy behaviors but have not generally encouraged a provider-driven approach.36 In subgroup analyses, respondents with chronic diseases responded similarly or more favorably to all aspects of HRA completion and experience. While addressing structural and environmental factors in combatting chronic disease is important, primary care providers play a valuable role—particularly among individuals with low socioeconomic status, where the burden of chronic disease is high.

Notably, HMP enrolls patients in managed care plans, many of which have extensive resources and experience in engaging enrollees in wellness programs. The availability and use of those resources may have improved enrollee participation in PCP visits, either through increased awareness, patient education, or other mechanisms. Moreover, managed care plan reimbursement was in part tied to quality performance metrics based upon the proportion of plan beneficiaries who saw their PCP following enrollment. These health plan incentives may have contributed to higher levels of recent PCP visits—and, in turn, higher HRA completion rates. Other states considering inclusion of healthy behavior incentives as part of Medicaid expansion may expect greater enrollee participation and engagement when participating managed care plans set an expectation for PCP interaction following enrollment.

A third finding is that enrollees were less likely to report that financial incentives were the reason for HRA completion, perhaps because of lack of awareness of the individual enrollee incentive. Other studies of Medicaid enrollees have shown financial incentives increase engagement in healthy behaviors.8,9,10,11 In this study, less than one-third of respondents reported awareness of financial incentives. Awareness of financial incentives was similarly low in Iowa’s healthy behavior incentive program, where low levels of HRA completion and healthy behavior engagement were also observed.16 However, HMP enrollees rarely attributed financial incentives to healthy behaviors even when they chose to participate: only 2.6% of HMP enrollees who completed an HRA reported gift cards and reductions in co-pays as motivators. The extent to which lack of awareness—versus lack of interest—limits the effectiveness of financial incentives remains uncertain but merits further study.

We found that enrollees who chose a healthy behavior were most likely to choose diet/nutrition or exercise/physical activity and less likely to choose preventive care or chronic disease management—a trend consistent among all respondents and those with chronic disease. Despite their known benefits,20 healthy behaviors, such as diet or physical activity, have been subject to communication barriers—even when providers report they have discussed these topics with their patients.37, 38 For HMP enrollees, these subjects were of greatest interest, even though choosing preventive services, such as receiving a flu vaccine, would arguably be easier to complete. Similarly, those with mental health or substance use disorders were more likely than those without to choose a healthy behavior related to tobacco, alcohol, or substance use reduction or cessation.39 These findings suggest enrollees may have insight into identifying health needs that are likely to provide them greater health benefits, and that interdisciplinary care to promote participation in healthy behaviors, where providers have limited effectiveness, may be helpful. More qualitative analysis is needed to understand motivations and reasons for choice of healthy behavior.

We note several limitations. The telephone survey format is subject to nonresponse bias if some groups are not well-represented in the responders. However, we weighted survey items for nonresponse to minimize such bias. Survey methods are subject to social desirability bias and all measures were self-reported; enrollees might therefore be less likely, for instance, to admit they did not choose to work on a healthy behavior. Respondents’ recollection of HRA completion and experiences with PCPs and HRAs may also be subject to recall bias. Further, this study did not assess reasons for not completing an HRA and did not include a control group. Another limitation is that using quantitative data to assess enrollee perceptions toward HRAs and reasons to engage in healthy behaviors may lack important details and dimensions that might be identified through more in-depth, open-ended qualitative analyses. Because this study evaluated HRA completion and healthy behavior engagement in one state Medicaid program, there may be state-specific contextual factors that limit generalizability elsewhere. Finally, the present study did not examine associations between participation in HRAs and actual changes in health behaviors40 or health outcomes. Because many healthy behaviors are difficult to operationalize, actual changes in healthy behaviors are likely attenuated from a healthy behavior commitment.

CONCLUSION

Implementation of the Healthy Michigan Plan was associated with high levels of enrollee-reported HRA completion and commitment to healthy behaviors. Enrollees reported that providers were influential at each stage of the HRA experience, including HRA completion and decisions to engage in a healthy behavior. Enrollees also reported that completing HRAs helped their providers understand their health needs. For HMP enrollees, awareness and influence of financial incentives for HRA completion and healthy behavior engagement were limited. Additional study is needed to understand the relative importance of financial incentives and PCP engagement in impacting healthy behaviors in state Medicaid programs.

References

Ayanian JZ. Michigan’s approach to Medicaid expansion and reform. N Engl J Med. 2013 Nov 7;369(19):1773–5.

Galewitz P. Michigan To Reward Medicaid Enrollees Who Take ‘Personal Responsibility’. Kaiser Health News. 2014 June 11. Accessed at https://khn.org/news/michigan-to-reward-medicaid-enrollees-who-take-personal-responsibility/ on October 21, 2019.

Moniz MH, Kirch MA, Solway E, et al. Association of access to family planning services with medicaid expansion among female enrollees in michigan. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(4):e181627.

Special Terms and Conditions: Healthy Michigan Section 1115 Demonstration, (2016). Michigan Department of Health & Human Services. Accessed at https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdhhs/Healthy_Michigan_Plan_2nd_Waiver_STCs_12_17_15_508663_7.pdf on October 21, 2019.

Contreary K, Miller R. Incentives to Change Health Behaviors: Beneficiary Engagement Strategies in Indiana, Iowa, and Michigan. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2017 August. Accessed at https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demo/downloads/evaluation-reports/incentives-to-change-health-behaviors.pdf on October 21, 2019.

Musumeci M, Rudowitz R, Ubri P, Hinton E. An Early Look at Medicaid Expansion Waiver Implementation in Michigan and Indiana. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2017 January. Accessed at https://www.kff.org/report-section/an-early-look-at-medicaid-expansion-waiver-implementation-in-michigan-and-indiana-key-findings/ on October 21, 2019.

Healthy Michigan Plan Healthy Behaviors Incentives Operational Protocol: ATTACHMENT B, (2014). Michigan Department of Health & Human Services. Accessed at https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdhhs/Attachment_B_-_Revised_Healthy_Behaviors_Incentive_Protocol-Clean_632146_7.pdf on October 21, 2019.

Van Vleet A, Rudowitz R. An Overview of Medicaid Incentives for the Prevention of Chronic Diseases (MIPCD) Grants. The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2014 September 16. Accessed at https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/an-overview-of-medicaid-incentives-for-the-prevention-of-chronic-diseases-mipcd-grants/ on October 21, 2019.

Saunders R, Vulimiri M, Japinga M, Bleser W, Wong C. Are carrots good for your health? Current evidence on health behavior incentives in the Medicaid Program. Margolis Center for Health Policy, Duke University, 2018 June. Accessed at https://healthpolicy.duke.edu/sites/default/files/atoms/files/duke_healthybehaviorincentives_6.1.pdf on October 21, 2019.

The Use of Healthy Behavior Incentives in Medicaid. MACPAC: Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, 2016 August. Accessed at https://www.macpac.gov/publication/the-use-of-healthy-behavior-incentives-in-medicaid/ on October 21, 2019.

Blumenthal KJ, Saulsgiver KA, Norton L, Troxel AB, Anarella JP, Gesten FC, et al. Medicaid incentive programs to encourage healthy behavior show mixed results to date and should be studied and improved. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013 Mar;32(3):497–507.

Halpern SD, Harhay MO, Saulsgiver K, Brophy C, Troxel AB, Volpp KG. A pragmatic trial of e-cigarettes, incentives, and drugs for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jun 14;378(24):2302–10.

Bradley CJ, Neumark D. Small cash incentives can encourage primary care visits by low-income people with new health care coverage. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017 Aug 1;36(8):1376–84.

Barte JCM, Wendel-Vos GCW. A systematic review of financial incentives for physical activity: the effects on physical activity and related outcomes. Behav Med. 2017 Apr-Jun;43(2):79–90.

Kane RL, Johnson PE, Town RJ, Butler M. A structured review of the effect of economic incentives on consumers’ preventive behavior. Am J Prev Med. 2004 Nov;27(4):327–52.

Askelson NM, Wright B, Bentler S, Momany ET, Damiano P. Iowa’s Medicaid expansion promoted healthy behaviors but was challenging to implement and attracted few participants. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017 May 1;36(5):799–807.

Updated Health Risk Assessment. Healthy Michigan Plan: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. Accessed at https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdhhs/HMP_HRA_FACT_SHEET_619607_7.pdf on October 21, 2019.

Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, Diamant M, Ferrannini E, Nauck M, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centred approach. Update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetologia. 2015 Mar;58(3):429–42.

Lanier JB, Bury DC, Richardson SW. Diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention. Am Fam Physician. 2016 Jun 1;93(11):919–24.

Dunkler D, Dehghan M, Teo KK, Heinze G, Gao P, Kohl M, et al. Diet and kidney disease in high-risk individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA Intern Med. 2013 Oct 14;173(18):1682–92.

Goold SD, Tipirneni R, Kieffer E, Haggins A, Salman C, Solway E, et al. Primary care clinicians’ views about the impact of Medicaid expansion in Michigan: a mixed methods study. J Gen Intern Med. 2018 Aug;33(8):1307–16.

Goold SD, Kullgren J, Clark S, Mrukowicz C. Healthy Michigan Voices Beneficiary Survey: Interim Report. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016 September 15. Accessed at https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/mi/Healthy-Michigan/mi-healthy-michigan-benef-survey-interim-report-09212016.pdf on October 21, 2019.

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007–2016. In: National Center for Health Statistics, editor. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2019. Accessed at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm on October 21, 2019.

Health Tracking Household Survey, 2010 [United States]. In: Center for Studying Health System Change, editor. University of Michigan: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; 2012. Accessed at https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/HMCA/studies/34141 on October 21, 2019.

Selected diseases and conditions among adults aged 18 and over, by selected characteristics: United States, 2016. National Health Interview Survey: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/shs/tables.htm on October 21, 2019.

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. Accessed at https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/index.html on October 21, 2019.

Michigan Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Michigan Department of Health & Human Services; 2010–2019. Accessed at https://www.michigan.gov/mdhhs/0,5885,7-339-71550_5104_5279_39424---,00.html on October 21, 2019.

Turner-Bowker D, Hogue SJ. Short Form 12 Health Survey (SF-12). In: Michalos AC, editor. Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2014. p. 5954–7.

Food Attitudes and Behaviors (FAB) Survey. National Cancer Institute: National Institutes of Health; 2009. Accessed at https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/hbrb/fab/ on October 21, 2019.

Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; 1995–2019. Accessed at https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/about-cahps/index.html on October 21, 2019.

EBRI/Greenwald Consumer Engagement in Health Care Survey. Employee Benefit Research Institute; 2008–2018. Accessed at https://www.ebri.org/health/ebri-greenwald-consumer-engagement-healthcare-survey on October 21, 2019.

Health Care Quality Survey. The Commonwealth Fund; 2001. Accessed at https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/surveys/2002/mar/2001-health-care-quality-survey on October 21, 2019.

The American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. Oakbrook Terrace (IL); 2016. Accessed at http://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions20169theditionfinal.pdf on October 21, 2019.

Tipirneni R, Kullgren JT, Ayanian JZ, Kieffer EC, Rosland AM, Chang T, et al. Changes in health and ability to work among Medicaid expansion enrollees: a mixed methods study. J Gen Intern Med. 2019 Feb;34(2):272–80.

National Committee for Quality Assurance. Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures. 2018. Accessed at http://www.ncqa.org/HEDISQualityMeasurement.aspx on October 21, 2019.

Bauer UE, Briss PA, Goodman RA, Bowman BA. Prevention of chronic disease in the 21st century: elimination of the leading preventable causes of premature death and disability in the USA. Lancet. 2014 Jul 5;384(9937):45–52.

Greiner KA, Born W, Hall S, Hou Q, Kimminau KS, Ahluwalia JS. Discussing weight with obese primary care patients: physician and patient perceptions. J Gen Intern Med. 2008 May;23(5):581–7.

Carroll JK, Fiscella K, Meldrum SC, Williams GC, Sciamanna CN, Jean-Pierre P, et al. Clinician-patient communication about physical activity in an underserved population. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008 Mar-Apr;21(2):118–27.

Guydish J, Passalacqua E, Pagano A, Martinez C, Le T, Chun J, et al. An international systematic review of smoking prevalence in addiction treatment. Addiction. 2016 Feb;111(2):220–30.

Baker AM, Hunt LM. Counterproductive consequences of a conservative ideology: Medicaid expansion and personal responsibility requirements. Am J Public Health. 2016 Jul;106(7):1181–7.

Funding

The University of Michigan Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation (IHPI) is conducting the evaluation required by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) of the Healthy Michigan Plan (HMP) under contract with the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS). Data collected for this paper was funded by MDHHS and CMS for the purposes of the evaluation but does not represent the official views of either agency. ATK is supported through the National Clinician Scholars Program at the University of Michigan and VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System; SD is supported by the Healthy Michigan Plan Evaluation; JZA is supported by the Healthy Michigan Plan Evaluation; MP is supported by the Healthy Michigan Plan Evaluation and an R01 research award from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (1 R01 DK116715-01A1); EB is supported by the Healthy Michigan Plan Evaluation; TC the Healthy Michigan Plan Evaluation is supported by a K23 Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (1 K23 HD083527-01A1); ES is supported by the Healthy Michigan Plan Evaluation; RT the Healthy Michigan Plan Evaluation is supported by a K08 Clinical Scientist Development Award (1 K08 AG056591-01) from the National Institute on Aging.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Corey Bryant, MS; Sarah Clark, MPH; Sunghee Lee, PhD, MS; and Matthias Kirch, MS, from the Healthy Michigan Plan Evaluation Team at the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation at the University of Michigan, provided review and feedback for the study design and manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of MDHHS or the United States government.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations

None

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 102 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kelley, A.T., Goold, S.D., Ayanian, J.Z. et al. Engagement with Health Risk Assessments and Commitment to Healthy Behaviors in Michigan’s Medicaid Expansion Program. J GEN INTERN MED 35, 514–522 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05562-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05562-x