Abstract

Background

Telehealth employs technology to connect patients to the right healthcare resources at the right time. Women are high utilizers of healthcare with gender-specific health issues that may benefit from the convenience and personalization of telehealth. Thus, we produced an evidence map describing the quantity, distribution, and characteristics of evidence assessing the effectiveness of telehealth services designed for women.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE® (via PubMed®) and Embase® from inception through March 20, 2018. We screened systematic reviews (SRs), randomized trials, and quasi-experimental studies using predetermined eligibility criteria. Articles meeting inclusion criteria were identified for data abstraction. To assess emerging trends, we also conducted a targeted search of ClinicalTrials.gov.

Results

Two hundred thirty-four primary studies and three SRs were eligible for abstraction. We grouped studies into focused areas of research: maternal health (n = 96), prevention (n = 46), disease management (n = 63), family planning (n = 9), high-risk breast cancer assessment (n = 10), intimate partner violence (n = 7), and mental health (n = 3). Most interventions focused on phone as the primary telehealth modality and featured healthcare team-to-patient communication and were limited in duration (e.g., < 12 weeks). Few interventions were conducted with older women (≥ 60 years) or in racially/ethnically diverse populations. There are few SRs in this area and limited evidence regarding newer telehealth modalities such as mobile-based applications or short message service/texting. Targeted search of clinical.trials.gov yielded 73 ongoing studies that show a shift in the use of non-telephone modalities.

Discussion

Our systematic evidence map highlights gaps in the existing literature, such as a lack of studies in key women’s health areas (intimate partner violence, mental health), and a dearth of relevant SRs. With few existing SRs in this literature, there is an opportunity for examining effects, efficiency, and acceptability across studies to inform efforts at implementing telehealth for women.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Telehealth is an important mechanism for delivering patient-centered healthcare outside of time and location restrictions of a traditional face-to-face medical encounter. According to the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration, telehealth is defined as “the use of electronic information and telecommunication technologies to support and promote long-distance clinical healthcare, patient and professional health-related education, public health and health administration.”1 Telehealth encompasses a variety of technologies and approaches to connect patients to healthcare resources with the goal of improving personalization, efficiency, access to care, and secure sharing of health information. Nationally, telehealth strategies have flourished due to an increased emphasis on efficient healthcare delivery in recent health policies.2

Telehealth has the ability to personalize healthcare via delivering the right intervention to the right patient at the right time.3 Women are one population that may benefit from individualized tailoring offered by telehealth approaches. They have gender-specific healthcare needs due to biologic and sociocultural characteristics, are high utilizers of healthcare, and are more likely than men to use mobile applications or search for health information online.4, 5 Telehealth is well suited to overcome barriers to obtaining healthcare that are frequently reported by women, such as competing demands.6, 7 Yet, women may need gender-specific approaches to optimize engagement with certain telehealth technologies.8 Which types of telehealth interventions are most effective in women is unknown.

As an initial step toward understanding the effectiveness of telehealth for women, we sought to describe the current landscape of telehealth interventions designed specifically for women using an evidence mapping approach. In keeping with the principles of evidence mapping,9 we provide high-level information across a broad literature in this area rather than seeking detailed information on a narrow set of questions. Thus, our specific question for this evidence map was: What are the quantity, distribution, and characteristics of evidence assessing the effectiveness of telehealth services designed specifically for women?

METHODS

This work is an update of a larger project for the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Evidence-based Synthesis Program (ESP). The original technical report is available at https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp and includes a more detailed discussion of our methodology. We followed a standard protocol (PROSPERO registration number CRD42017065965). We pilot-tested each step to train and calibrate study investigators.

Definitions

Here, we define key terms used in this study. We acknowledge the conceptual differences between sex and gender;10 however, because this evidence map describes literature across conditions and diagnoses, we opted to use “gender” to be inclusive of social and cultural experiences of relevant conditions in addition to their biologic basis. We operationalized “designed specifically for women” to mean interventions organized around one of three conditions: (1) female-only conditions (e.g., pregnancy), (2) female-predominant conditions (e.g., breast cancer), or (3) interventions targeting conditions that affect both sexes (e.g., diabetes) but customized for, and assessed solely among, women. This last category of conditions was included due to the growing awareness of gender-based variability in pathophysiology and experience of disease processes (e.g., acute coronary disease). We purposely omitted telehealth interventions delivered to mixed-gender populations, because our prior work suggests we would be unlikely to find a significant yield of relevant gender-effect subanalyses.11

Because telehealth can encompass a wide variety of strategies and approaches in the context of healthcare, we operationalized telehealth broadly. Specifically, we defined telehealth as any bidirectional technology used to synchronously or asynchronously transmit clinical information across a distance between patients and members of the medical/mental healthcare team or provider-to-provider interactions for the purpose of diagnosis, consultation, treatment, and/or prevention. Examples of telehealth technologies are telephone, short message service (SMS)/text messaging, video conferencing, and interactive voice response systems. We excluded interventions that solely delivered educational content or that were unidirectional (e.g., static websites).

Finally, we considered telehealth to be a central intervention component when the telehealth technologies (e.g., text messaging) were the primary mode of intervention delivery, and any non-telehealth components (e.g., written materials) played a minor role in relaying intervention content, impacting outcomes, or delivering healthcare. Telehealth was considered non-central if the above criteria were not met.

Data Sources and Searches

In collaboration with an expert reference librarian, we searched MEDLINE® (via PubMed®) and Embase® to identify relevant articles and systematic reviews (SRs) published between inception and March 20, 2018. We used a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), keywords, and selected free-text terms for women’s health and telemedicine (Appendix 1). To identify ongoing studies, we also conducted a targeted search of www.clinicaltrials.gov between inception and March 26, 2018. We used keywords related to telehealth modalities and limited to those studies with projected enrollment of 100 or more and only recruiting women. All citations were imported into two electronic databases (for referencing, EndNote® version X7; Thomson Reuters, Philadelphia, PA; for data abstraction, DistillerSR; Evidence Partners, Inc., Manotick, ON, Canada).

Study Selection

Eligible studies included interventions that met our definitions of telehealth and were designed specifically for women. Because our Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) operational leadership partners were interested in the literature that assessed effectiveness, we limited our search to Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group criteria, which identifies study designs best suited to assess effects of health system interventions like telehealth.12 EPOC criteria include both randomized and non-randomized study designs with prospective data collection. Similarly, we limited our search to studies with at least 100 patient participants (regardless of whether the unit of randomization was at provider or system level). We included studies that had any type of comparator (e.g., active, usual care) and any follow-up duration and collected data on outcomes at the patient level (e.g., quality of life), provider level (e.g., provider satisfaction), or system level (e.g., utilization). See Appendix 2 for detailed prespecified eligibility criteria.

Two investigators independently evaluated titles and abstracts to identify potentially eligible primary studies and SRs. Studies advanced to full-text review if either reviewer identified it as meeting inclusion criteria. To be eligible at full-text review, studies had to meet all eligibility criteria. If we were unable to assess an eligibility criterion due to missing information, the study was excluded.

Due to the large volume of primary studies, we planned to pilot single-review screening at the full-text stage. We found an inter-rater reliability of 87% after the first 200 citations, which we deemed as an acceptable level to proceed with single full-text review. To preserve a rigorous full-text screening process, we conducted an ongoing evaluation through a random dual screening by another senior investigator (KMG, JMG). Interim examination of the random sample demonstrated continued high concordance on excluded studies but poor concordance on included studies. Thus, all studies categorized as included by single review went through a dual full-text review by senior investigators (KMG, JMG).

Two investigators examined the SRs separately. Disagreements were resolved by consensus between the two or by a third investigator if consensus could not be reached.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Data from primary studies meeting inclusion criteria were abstracted into a customized DistillerSR database by one investigator, and a random sample of 10% was over-read by one of three senior investigators. Data from SRs were abstracted into an Excel database and over-read by senior investigators. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or arbitrated by the study team.

We abstracted the following data elements: study design, intervention, comparator, outcomes reported, study population, communication dyad members (e.g., provider to patient), primary telehealth modality (e.g., telephone, texting), intervention timing (synchronous or asynchronous), interventionist, study size, study setting, and centrality of telehealth modality in a given intervention. For ongoing studies identified in the ClinicalTrials.gov search, we abstracted telehealth modality, outcome type, and country of recruitment. A formal assessment of individual study methodological rigor was beyond the scope of this mapping project; thus, we did not collect data to assess individual study quality.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

We mapped the literature that emerged from our search into the focused areas of research. Further, we identified 23 studies with more than one active telehealth arm.13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35 For these studies, we collapsed data across study arms so that each study is represented only one time in graphical depictions of the data. We summarize the data narratively and include tabular and graphical formats to convey key features of the literature.

Role of Funding Source

This project (VA-ESP 09-210; 2017) and the Durham VA Health Care System ESP are funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, which had no involvement in data collection, analysis, interpretation of results, or decision to submit this manuscript.

RESULTS

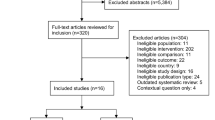

The literature search identified 5892 unique citations, and after screening at the abstract level, 821 primary studies and 22 SRs underwent full-text review. Of these, 234 studies and 3 SRs were retained for data abstraction (Fig. 1) and clustered in the following 7 focused areas of research: maternal health (96 primary studies, 1 SR), disease management (63 primary studies, 1 SR), prevention (46 primary studies), family planning (9 studies), assessment of women at high risk of breast cancer (10 studies), intimate partner violence (IPV) (7 primary studies, 1 SR), and mental health (3 studies). When study topics could have been categorized into more than one area of research, we categorized by the affected population (e.g., maternal health for interventions related to postpartum depression) and not by the target of the intervention (e.g., mental health). The earliest study meeting inclusion criteria were published in 1987. Additional details about individual studies are available in Appendix 3.

Primary Studies and Systematic Reviews

Participant Sociodemographic Characteristics of Women’s Telehealth Interventions

Across the literature on women’s telehealth interventions, the majority of published studies recruited 250 or fewer participants (n = 168, 71%). Age distributions were tracked with typical age onset for the relevant health condition. For example, maternal health studies were focused on women in their 20s and 30s. Yet, there was an overall trend of limited telehealth studies intervening on the health issues of women aged 60 years and older across the identified reports on prevention, disease management, mental health, and IPV. In addition, when mapping the race and ethnic composition, we found that only half of the studies reported the race and ethnic distribution (n = 111, 47%). For studies that did provide data on race distribution, most included populations were predominantly white (n = 80, 72%). Of note, nine studies targeted African-American women only.14, 36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43

Characteristics of Women’s Telehealth Interventions

Clear patterns emerged for key characteristics of telehealth centrality, modality, and focus of the treatment dyad. First, telehealth technologies were the central mode of intervention delivery across the majority of studies (n = 161, 69%). Next, across all areas of research, telephone was the dominant modality (n = 191, 82%) to deliver intervention content (Fig. 2). Non-phone modalities included interactive websites (n = 12, 5%), SMS/text messaging (n = 10, 4%), interactive mobile applications (n = 7, 3%), multiple modalities (n = 9, 4%), and other (n = 5, 2%). Of the studies using a primary telehealth modality other than telephone, all but two were published since 2010,44, 45 reflecting a paucity of adequately powered published literature assessing new and emerging telehealth technologies (Fig. 3). Most studies used telehealth technologies to facilitate communication between patients and healthcare team members (n = 200, 85%). Only three prevention-focused studies used telehealth to communicate from one healthcare provider to another (Fig. 4).15, 33, 46

Few studies exclusively used physicians or advanced practice providers (e.g., nurse practitioners, physician assistants) as a telehealth interventionist. Instead, interventions were mostly supported by a variety of credentialed (e.g., registered nurses, behavioral health specialists) and non-credentialed (e.g., health educators, peer or lay health workers) positions (n = 234, 99%). Of the 191 studies that reported intervention duration, the majority were limited in their duration and did not extend beyond 24 weeks (n = 125, 65%). The focused area of prevention was an exception, with most studies lasting 25 weeks or more in duration (n = 19, 40% reporting duration). The overwhelming majority of studies were conducted in countries categorized as high income by the World Bank47 (n = 202, 86%). The area of family planning was an exception as half of its studies were conducted in middle- and low-income countries (n = 5, 56%). Of those studies that clearly identified a primary outcome (n = 224), none use a provider-level outcome (e.g., provider satisfaction) and only 19 used a system-level outcome (e.g., access to care, utilization).

Three research areas (maternal health, prevention, disease management) made up 88% of this literature (n = 205). The most common intervention targets among maternal health studies were prenatal care (n = 26), lactation (n = 17), and peripartum mental health (n = 16). One SR addressed maternal mental health and evaluated Web-based treatments with interventionist support by either text or telephone for perinatal mood disorder.48 Over half of disease management interventions were related to breast cancer treatment and survivorship (n = 44, 69%). The next largest subcategory under disease management was cardiovascular disease/risk factors (e.g., hypertension, metabolic syndrome, or diabetes) with six studies (10%). One SR (n = 2002; published 201849) also focused on disease management and was a synthesis of randomized trials testing telephone interventions to improve quality of life for breast cancer patients. For prevention, there were 18 studies on increasing physical activity, 15 on cancer screening, and 13 on weight management. Of note, there were an additional 10 studies on peripartum weight management in the maternal health area and one study50 on weight management among breast cancer survivors in the disease management area. Between the maternal health- and prevention-focused studies, there were 20 studies on smoking cessation.

The remaining 12% of this literature (n = 27) fell into smaller research areas. Family planning included five studies addressing contraception use,51,52,53,54,55 two on assisted reproduction,56, 57 and two on abortion-related care.58, 59 High-risk breast cancer assessment included seven studies comparing in-person to telegenetic counseling,60,61,62,63,64,65,66 and two addressing the needs of women at high risk.67, 68 IPV included six studies that promoted the safety or well-being of women who had experienced IPV,69,70,71,72,73,74 and one study addressed post-exposure HIV prophylaxis.75 There was one SR that examined telephone interventions for preventing new HIV infection76 that identified this same study.

Grey Literature Search

Our targeted search of ClinicalTrials.gov produced 73 ongoing studies across the previously described areas of research: maternal health (n = 31, 42%), disease management (n = 22, 30%), prevention (n = 11, 15%), family planning (n = 3, 4%), high-risk breast cancer assessment (n = 3, 4%), mental health (n = 2, 3%), and IPV (n = 1, 1%). The most common subcategories among these ongoing trials include breast cancer care and survivorship (n = 14, 19%), weight management (n = 8 (7 peripartum), 11%), and peripartum mental health (n = 5, 7%). Of these 73 studies, 33 use phone as the telehealth modality (45% vs. 81% in published literature), 14 use multiple telehealth modalities (19%), 6 use videoconferencing (8%), 5 use an interactive mobile app (7%), 4 use interactive websites (5%), and 3 use other modalities (4%). Overall, 45% of active studies of telehealth interventions designed for women are using a non-telephone approach as the sole or contributing modality (Fig. 3). Fifty active studies plan patient-level outcomes only (68% vs. 80% published literature) and 18 measure patient- and system-level outcomes (25% vs. 20% published literature), while only three include any measures of provider-level outcomes.77,78,79

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first evidence map evaluating telehealth services designed specifically for women. We found that the majority of existing women’s telehealth interventions were related to maternal health, prevention, and disease management. Within those categories respectively, prenatal care, physical activity promotion, and breast cancer care and survivorship were most common and may offer opportunities for future evidence synthesis. Surprisingly, fewer published studies and trials underway targeted gender-specific telehealth approaches for mental health, IPV, family planning, and cardiovascular disease risk factors such as diabetes and hypertension. Overall, telehealth interventions enrolled predominately younger, white women; thus, there is a need for telehealth interventions addressing health needs among older (aged ≥ 60 years) and racially and ethnically diverse women. We also found that the telephone was the dominant telehealth modality across studies and that there is a dearth of evidence on alternative telehealth modalities such as interactive mobile-based apps or SMS/texting.

The integration of telehealth into routine healthcare is expected to increase, as is the breadth of modalities in use. For example, there is significant unrealized potential to incorporate wearable devices into the bidirectional telehealth communication loop, which would bring home-based vital status monitoring such as blood pressure and glucose directly to healthcare teams. We identified that the current literature has focused almost exclusively on the use of telephone to deliver gender-specific telehealth interventions. However, publication trends over time suggest an increasing number of studies testing women’s telehealth interventions with non-telephone modalities. Further, our search of ongoing clinical trials also suggests that this trend is shifting toward more non-telephone modalities. This is encouraging as it is critical that telehealth technology innovations be systematically evaluated for feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness among women before they can be widely disseminated in routine healthcare practice. For example, mobile applications for women’s health have undergone tremendous growth and addressed needs from postpartum sleep to oral contraceptive adherence80, 81; however, many such apps are not grounded in scientific evidence or informed by medical expertise.82, 83 New technologies may also create opportunities to improve healthcare access and engagement across cultural and socioeconomically diverse populations.84, 85 Thus, future work in women’s telehealth interventions would benefit from the inclusion of both newer telehealth modalities and diversity of patient populations.

Telehealth can facilitate the integration of non-traditional personnel resources to the healthcare team, potentially expanding the reach of traditional healthcare staffing resources. By triaging appropriate tasks to non-traditional healthcare team members, it also expands the capacity of physicians and advanced practice providers. However, we found that few studies measured provider-level outcomes, and no studies used provider-level outcomes as a primary outcome. The lack of provider-level outcomes limits the ability to understand how telehealth strategies for women are received by providers and if providers perceive these strategies as beneficial to optimize the efficiency and quality of clinical decision making.

The present literature on women’s telehealth interventions also does not routinely measure system-level outcomes. This is notable, given that telehealth interventions are often touted to increase access and efficiency. In addition, a robust understanding of the cost of telehealth interventions is critical for making implementation decisions on a larger scale.86 Thus, to pursue efficient dissemination and sustainability of tailored telehealth approaches, an informed, systems perspective is critical. To develop such an understanding, telehealth interventions need to be developed and tested in a variety of system-level contexts in order to have robust tools that will work in diverse healthcare settings. Large healthcare organizations that have invested heavily in the use of telehealth modalities (e.g., VHA, Kaiser87, 88) are well situated to support such outcomes assessment.

There is a need for more research using telehealth to improve long-term health outcomes. The brief duration of many interventions included in this review is a notable limitation of the current evidence on telehealth interventions for women. Short-term interventions are appropriate for time-limited conditions such as pregnancy or infections; however, chronic medical and mental health conditions often require follow-up over an extended time. Telehealth interventions that use less expensive modalities such as asynchronous mobile health or automated computer algorithms could enable this longer-term care while reducing the frequency of high-cost clinic visits.

While we conducted this review with high scientific rigor, our evidence map should be interpreted with caution for several reasons. First, there are multiple definitions of telehealth, and other ways of operationalizing telehealth may produce different results. Further, we only included study designs set forth by the Cochrane EPOC Group.12 It is possible that we excluded relevant studies that used other designs. We chose EPOC designs because these criteria provide a standardized mechanism by which to gauge the potential value of the study to define the effectiveness of telehealth strategies for women. In order to focus on studies large enough to provide meaningful findings, we limited our inclusion criteria to those studies that included at least 100 patients. While this would have allowed trials for which the unit of randomization was providers or systems, requiring a minimum number of patients may have excluded studies with relevant findings. Due to the size and scope of this review, it was not feasible to conduct dual review or abstraction of all studies. Consistent with other evidence maps, we did not provide summary estimates of effects.

A key use of these maps is to inform decisions about where additional primary research is needed. Future research about the field of telehealth interventions for women is warranted in areas across the lifespan, including family planning, geriatric healthcare, and mental health. In addition, there is a need to test telehealth strategies in more diverse patient populations and contexts. Finally, studies exploring the use of newer telehealth modalities that enroll more diverse patient populations and which measure provider- and system-level outcomes would add significance to this literature. Coordinated efforts by funding agencies and investigators to plan patient-level meta-analyses could leverage existing resources to efficiently address some of these research gaps.

References

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Health Resources & Services Adminstration: Telehealth Programs. Available at https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/telehealth/index.html. Accessed 17 July 2018.

Weinstein RS, Lopez AM, Joseph BA, et al. Telemedicine, telehealth, and mobile health applications that work: opportunities and barriers. Am J Med. 2014;127(3):183–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.09.032

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). National Health IT Day. June 7, 2006. Available at: https://archive.ahrq.gov/news/sp060706.htm. Accessed 17 July 2018.

Escoffery C. Gender Similarities and Differences for e-Health Behaviors Among U.S. Adults. Telemed J E Health. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2017.0136

Kontos E, Blake KD, Chou WY, Prestin A. Predictors of eHealth usage: insights on the digital divide from the Health Information National Trends Survey 2012. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(7):e172. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3117

Pan IW, Smith BD, Shih YC. Factors contributing to underuse of radiation among younger women with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(1):djt340. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djt340

Stone RI, Short PF. The competing demands of employment and informal caregiving to disabled elders. Med Care. 1990;28(6):513–26.

Guo X, Han X, Zhang X, Dang Y, Chen C. Investigating m-Health Acceptance from a Protection Motivation Theory Perspective: Gender and Age Differences. Telemed J E Health. 2015;21(8):661–9. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2014.0166

Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Shanman R, Shekelle PG. What is an evidence map? A systematic review of published evidence maps and their definitions, methods, and products. Syst Rev. 2016;528. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0204-x

Clayton JA, Tannenbaum C. Reporting Sex, Gender, or Both in Clinical Research? JAMA. 2016;316(18):1863–1864. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.16405

Duan-Porter W, Goldstein KM, McDuffie JR, et al. Reporting of Sex Effects by Systematic Reviews on Interventions for Depression, Diabetes, and Chronic Pain. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(3):184–93. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-2877

EPOC. Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). EPOC Resources for review authors. Oslo: Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services; 2015. Available at: http://epoc.cochrane.org/resources/epoc-resources-review-authors. Accessed 17 July 2018.

Simmons D, Devlieger R, van Assche A, et al. Effect of physical activity and/or healthy eating on GDM risk: The DALI Lifestyle Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016jc20163455. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2016-3455

Wilbur J, Miller AM, Fogg L, et al. Randomized Clinical Trial of the Women’s Lifestyle Physical Activity Program for African-American Women: 24- and 48-Week Outcomes. Am J Health Promot. 2016;30(5):335–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117116646342

Tso LS, Loi D, Mosley DG, et al. Evaluation of a Nationwide Pharmacist-Led Phone Outreach Program to Improve Osteoporosis Management in Older Women with Recently Sustained Fractures. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(9):803–10. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2015.21.9.803

Freeman LW, White R, Ratcliff CG, et al. A randomized trial comparing live and telemedicine deliveries of an imagery-based behavioral intervention for breast cancer survivors: reducing symptoms and barriers to care. Psychooncology. 2015;24(8):910–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3656

Reeder JA, Joyce T, Sibley K, Arnold D, Altindag O. Telephone peer counseling of breastfeeding among WIC participants: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):e700–9. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-4146

Snaith VJ, Hewison J, Steen IN, Robson SC. Antenatal telephone support intervention with and without uterine artery Doppler screening for low risk nulliparous women: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14121. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-121

Baker TB, Hawkins R, Pingree S, et al. Optimizing eHealth breast cancer interventions: which types of eHealth services are effective? Transl Behav Med. 2011;1(1):134–145.

Kimman ML, Dirksen CD, Voogd AC, et al. Economic evaluation of four follow-up strategies after curative treatment for breast cancer: results of an RCT. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(8):1175–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2010.12.017

Kimman ML, Dirksen CD, Voogd AC, et al. Nurse-led telephone follow-up and an educational group programme after breast cancer treatment: results of a 2 x 2 randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(7):1027–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2010.12.003

Hawkins RP, Pingree S, Shaw B, et al. Mediating processes of two communication interventions for breast cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81 Suppl:S48–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2010.10.021

Sherman DW, Haber J, Hoskins CN, et al. The effects of psychoeducation and telephone counseling on the adjustment of women with early-stage breast cancer. Appl Nurs Res. 2012;25(1):3–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2009.10.003

Sandgren AK, McCaul KD. Long-term telephone therapy outcomes for breast cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2007;16(1):38–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1038

Dietrich AJ, Tobin JN, Cassells A, et al. Telephone care management to improve cancer screening among low-income women: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(8):563–71.

Conn VS, Burks KJ, Minor MA, Mehr DR. Randomized trial of 2 interventions to increase older women’s exercise. Am J Health Behav. 2003;27(4):380–8.

Samarel N, Tulman L, Fawcett J. Effects of two types of social support and education on adaptation to early-stage breast cancer. Res Nurs Health. 2002;25(6):459–70. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.10061

Valanis BG, Glasgow RE, Mullooly J, et al. Screening HMO women overdue for both mammograms and pap tests. Prev Med. 2002;34(1):40–50. https://doi.org/10.1006/pmed.2001.0949

Ershoff DH, Quinn VP, Boyd NR, Stern J, Gregory M, Wirtschafter D. The Kaiser Permanente prenatal smoking-cessation trial: when more isn’t better, what is enough? Am J Prev Med. 1999;17(3):161–8.

Hawkins RP, Pingree S, Baker TB, et al. Integrating eHealth with human services for breast cancer patients. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1(1):146–154.

Nicolau AIO, Lima TM, Vasconcelos CTM, Carvalho FHC, Aquino PS, Pinheiro AKB. Telephone interventions in adherence to receiving the Pap test report: a randomized clinical trial. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2017;25e2948. https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.1845.2948

Rasouli M, AtashSokhan G, Keramat A, Khosravi A, Fooladi E, Mousavi SA. The impact of motivational interviewing on participation in childbirth preparation classes and having a natural delivery: a randomised trial. BJOG. 2017;124(4):631–639. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14397

Atnafu A, Otto K, Herbst CH. The role of mHealth intervention on maternal and child health service delivery: findings from a randomized controlled field trial in rural Ethiopia. Mhealth. 2017;339. https://doi.org/10.21037/mhealth.2017.08.04

Han JY, Hawkins R, Baker T, Shah DV, Pingree S, Gustafson DH. How Cancer Patients Use and Benefit from an Interactive Cancer Communication System. J Health Commun. 2017;22(10):792–799. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2017.1360413

Sreedevi A, Unnikrishnan AG, Karimassery SR, Deepak KS. The Effect of Yoga and Peer Support Interventions on the Quality of Life of Women with Diabetes: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2017;21(4):524–530. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijem.IJEM_28_17

Patel MR, Song PX, Sanders G, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a culturally responsive intervention for African American women with asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;118(2):212–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2016.11.016

Steinberg DM, Christy J, Batch BC, et al. Preventing Weight Gain Improves Sleep Quality Among Black Women: Results from a RCT. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(4):555–566. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-017-9879-z

Lutes LD, Cummings DM, Littlewood K, Dinatale E, Hambidge B. A Community Health Worker-Delivered Intervention in African American Women with Type 2 Diabetes: A 12-Month Randomized Trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25(8):1329–1335. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21883

Steinberg DM, Levine EL, Lane I, et al. Adherence to self-monitoring via interactive voice response technology in an eHealth intervention targeting weight gain prevention among Black women: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(4):e114. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2996

Parra-Medina D, Wilcox S, Salinas J, et al. Results of the Heart Healthy and Ethnically Relevant Lifestyle trial: a cardiovascular risk reduction intervention for African American women attending community health centers. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(10):1914–21. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2011.300151

Schover LR, Rhodes MM, Baum G, et al. Sisters Peer Counseling in Reproductive Issues After Treatment (SPIRIT): a peer counseling program to improve reproductive health among African American breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2011;117(21):4983–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26139

Skelly AH, Carlson J, Leeman J, Soward A, Burns D. Controlled trial of nursing interventions to improve health outcomes of older African American women with type 2 diabetes. Nurs Res. 2009;58(6):410–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181bee597

Muender MM, Moore ML, Chen GJ, Sevick MA. Cost-benefit of a nursing telephone intervention to reduce preterm and low-birthweight births in an African American clinic population. Prev Med. 2000;30(4):271–6. https://doi.org/10.1006/pmed.2000.0637

Alemi F, Stephens RC, Javalghi RG, Dyches H, Butts J, Ghadiri A. A randomized trial of a telecommunications network for pregnant women who use cocaine. Med Care. 1996;34(10 Suppl):Os10–20.

Davidson KW, Holderby AD, Willis S, et al. Three top Canadian and personal health concerns of a random sample of Nova Scotian women. Can J Public Health. 2001;92(1):53–6.

Prinja S, Nimesh R, Gupta A, Bahuguna P, Gupta M, Thakur JS. Impact of m-health application used by community health volunteers on improving utilisation of maternal, new-born and child health care services in a rural area of Uttar Pradesh, India. Trop Med Int Health. 2017;22(7):895–907. https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.12895

World Bank. How does the World Bank classify countries? Available at: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/378834-how-does-the-world-bank-classify-countries. Accessed 17 July 2018.

Lee EW, Denison FC, Hor K, Reynolds RM. Web-based interventions for prevention and treatment of perinatal mood disorders: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;1638. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0831-1

Zhang Q, Zhang L, Yin R, Fu T, Chen H, Shen B. Effectiveness of telephone-based interventions on health-related quality of life and prognostic outcomes in breast cancer patients and survivors-A meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018;27(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12632

Fazzino TL, Fabian C, Befort CA. Change in Physical Activity During a Weight Management Intervention for Breast Cancer Survivors: Association with Weight Outcomes. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25 Suppl 2:S109-s115. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22007

Tsur L, Kozer E, Berkovitch M. The effect of drug consultation center guidance on contraceptive use among women using isotretinoin: a randomized, controlled study. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(4):579–84. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2007.0623

Sridhar A, Chen A, Forbes ER, Glik D. Mobile application for information on reversible contraception: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(6):774.e1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.01.011

Smith C, Ngo TD, Gold J, et al. Effect of a mobile phone-based intervention on post-abortion contraception: a randomized controlled trial in Cambodia. Bull World Health Organ. 2015;93(12):842-50a. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.15.160267

Hameed W, Azmat SK, Ali M, et al. Comparing Effectiveness of Active and Passive Client Follow-Up Approaches in Sustaining the Continued Use of Long Acting Reversible Contraceptives (LARC) in Rural Punjab: A Multicentre, Non-Inferiority Trial. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0160683. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0160683

Berenson AB, Rahman M. A randomized controlled study of two educational interventions on adherence with oral contraceptives and condoms. Contraception. 2012;86(6):716–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2012.06.007

Skiadas CC, Terry K, De Pari M, et al. Does emotional support during the luteal phase decrease the stress of in vitro fertilization? Fertil Steril. 2011;96(6):1467–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.09.028

Gerris J, Delvigne A, Dhont N, et al. Self-operated endovaginal telemonitoring versus traditional monitoring of ovarian stimulation in assisted reproduction: an RCT. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(9):1941–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deu168

Ngoc NT, Bracken H, Blum J, et al. Acceptability and feasibility of phone follow-up after early medical abortion in Vietnam: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(1):88–95. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000000050

Paul M, Iyengar K, Essén B, et al. Acceptability of home-assessment post medical abortion and medical abortion in a low-resource setting in Rajasthan, India. Secondary outcome analysis of a non-inferiority randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:9 Article Number: e0133354.

Chang Y, Near AM, Butler KM, et al. Economic Evaluation Alongside a Clinical Trial of Telephone Versus In-Person Genetic Counseling for BRCA1/2 Mutations in Geographically Underserved Areas. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(1):59, e1-13. https://doi.org/10.1200/jop.2015.004838

Jenkins J, Calzone KA, Dimond E, et al. Randomized comparison of phone versus in-person BRCA1/2 predisposition genetic test result disclosure counseling. Genet Med. 2007;9(8):487–95. https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e31812e6220

Kinney AY, Butler KM, Schwartz MD, et al. Expanding access to BRCA1/2 genetic counseling with telephone delivery: a cluster randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(12). https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju328

Schwartz MD, Valdimarsdottir HB, Peshkin BN, et al. Randomized noninferiority trial of telephone versus in-person genetic counseling for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(7):618–26. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2013.51.3226

Peshkin BN, Kelly S, Nusbaum RH, et al. Patient Perceptions of Telephone vs. In-Person BRCA1/BRCA2 Genetic Counseling. J Genet Couns. 2016;25(3):472–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-015-9897-6

Kinney AY, Steffen LE, Brumbach BH, et al. Randomized Noninferiority Trial of Telephone Delivery of BRCA1/2 Genetic Counseling Compared With In-Person Counseling: 1-Year Follow-Up. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(24):2914–24. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2015.65.9557

Helmes AW, Culver JO, Bowen DJ. Results of a randomized study of telephone versus in-person breast cancer risk counseling. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;64(1–3):96–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2005.12.002

Bloom JR, Stewart SL, Chang S, You M. Effects of a telephone counseling intervention on sisters of young women with breast cancer. Prev Med. 2006;43(5):379–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.07.002

White VM, Young MA, Farrelly A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a telephone-based peer-support program for women carrying a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation: impact on psychological distress. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(36):4073–80. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2013.54.1607

McFarlane J, Malecha A, Gist J, et al. Increasing the safety-promoting behaviors of abused women. Am J Nurs. 2004;104(3):40–50.

Stevens J, Scribano PV, Marshall J, Nadkarni R, Hayes J, Kelleher KJ. A Trial of Telephone Support Services to Prevent Further Intimate Partner Violence. Violence Against Women. 2015;21(12):1528–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801215596849

Saftlas AF, Harland KK, Wallis AB, Cavanaugh J, Dickey P, Peek-Asa C. Motivational interviewing and intimate partner violence: a randomized trial. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24(2):144–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.10.006

Tiwari A, Yuk H, Pang P, et al. Telephone intervention to improve the mental health of community-dwelling women abused by their intimate partners: a randomised controlled trial. Hong Kong Med J. 2012;18 Suppl 6:14–7.

Tiwari A, Fong DY, Yuen KH, et al. Effect of an advocacy intervention on mental health in Chinese women survivors of intimate partner violence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304(5):536–43. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.1052

Koziol-McLain J, Vandal AC, Wilson D, et al. Efficacy of a Web-Based Safety Decision Aid for Women Experiencing Intimate Partner Violence: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2018;19(12):e426. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.8617

Abrahams N, Jewkes R, Lombard C, Mathews S, Campbell J, Meel B. Impact of telephonic psycho-social support on adherence to post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) after rape. AIDS Care. 2010;22(10):1173–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121003692185

van-Velthoven MH, Tudor Car L, Gentry S, Car J. Telephone delivered interventions for preventing HIV infection in HIV-negative persons. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(5):Cd009190. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009190.pub2

ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT02667626. Reproductive Health Survivorship Care Plan. Available at: https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT02667626. Accessed 17 July 2018.

ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT03435380. Promoting Breast Cancer Screening in Women Who Survived Childhood Cancer. Available at: https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03435380. Accessed 17 July 2018.

ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT03334149. Blood Pressure Monitoring in High Risk Pregnancy to Improve the Detection and Monitoring of Hypertension. Available at: https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03334149. Accessed 17 July 2018.

Gal N, Zite NB, Wallace LS. Evaluation of smartphone oral contraceptive reminder applications. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2015;11(4):584–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2014.11.001

O’Donnell BE, Lewkowitz AK, Vargas JE, Zlatnik MG. Examining pregnancy-specific smartphone applications: what are patients being told? J Perinatol. 2016;36(10):802–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2016.77

Subhi Y, Bube SH, Rolskov Bojsen S, Skou Thomsen AS, Konge L. Expert Involvement and Adherence to Medical Evidence in Medical Mobile Phone Apps: A Systematic Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3(3):e79. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.4169

Moglia ML, Nguyen HV, Chyjek K, Chen KT, Castano PM. Evaluation of Smartphone Menstrual Cycle Tracking Applications Using an Adapted APPLICATIONS Scoring System. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(6):1153–60. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000001444

Graetz I, Huang J, Brand RJ, Hsu J, Yamin CK, Reed ME. Bridging the digital divide: mobile access to personal health records among patients with diabetes. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(1):43–48.

Chang E, Blondon K, Lyles CR, Jordan L, Ralston JD. Racial/ethnic variation in devices used to access patient portals. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(1):e1-e8.

Licurse AM, Mehrotra A. The Effect of Telehealth on Spending: Thinking Through the Numbers. Ann Intern Med. 2018. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-3070

Pearl R. Kaiser Permanente Northern California: current experiences with internet, mobile, and video technologies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(2):251–7. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1005

Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. State of Telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):154–61. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1601705

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Megan Von Isenburg for the assistance with the literature search and retrieval, Jennifer McDuffie for the support in conducting this project during all phases, Angela Zoss for the data visualization assistance, and Liz Wing for the editorial assistance. We also thank the study participants who volunteered to be a part of the research described here. Additionally, we would like to thank the following key stakeholders and technical expert panel members for their feedback during the development and execution of this project: Lori Bastian, Alicia Christy, Kathy Frisbee, Sally Haskell, Jan Lindsay, Nancy Maher, Carolyn Turvey, and Alan West.

Funding

Drs. Zullig and Goldstein are supported by Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Career Development Awards (CDA) (CDA 13-025 and CDA 13-263, respectively). Dr. Dedert is supported by a CSR&D Service of the VA Office of Research and Development Career Development Award (Number 1IK2CX000718). Dr. Bosworth is supported by a VA HSR&D Research Career Scientist (RCS) Award (RCS 08-027). Dr. Whited is supported by a VA HSR&D Award (SD 16-192). This work was supported by the Center of Innovation for Health Services Research in Primary Care (CIN 13-410) at the Durham VA and the VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program (ESP 09-010). The primary source of funding for this work was the VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program (ESP 09-010). This work was also supported by the Center of Innovation for Health Services Research in Primary Care (CIN 13-410).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Whited is a co-editor of Teledermatology: A User’s Guide published by Cambridge University Press and receives royalties based on sales. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the United States government, or Duke University.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 413 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goldstein, K.M., Zullig, L.L., Dedert, E.A. et al. Telehealth Interventions Designed for Women: an Evidence Map. J GEN INTERN MED 33, 2191–2200 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4655-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4655-8