Abstract

Background

Deintensification of diabetic therapy is often clinically appropriate for older adults, because the benefit of aggressive diabetes treatment declines with age, while the risks increase.

Objective

We examined rates of overtreatment and deintensification of therapy for older adults with diabetes, and whether these rates differed by medical, demographic, and socioeconomic characteristics.

Design, Subjects, and Main Measures

We analyzed Medicare claims data from 10 states, linked to outpatient laboratory values to identify patients potentially overtreated for diabetes (HbA1c < 6.5% with fills for any diabetes medications beyond metformin, 1/1/2011–6/30/2011). We examined characteristics associated with deintensification for potentially overtreated diabetic patients. We used multinomial logistic regression to examine whether patient characteristics associated with overtreatment of diabetes differed from those associated with undertreatment (i.e. HbA1c > 9.0%).

Key Results

Of 78,792 Medicare recipients with diabetes, 8560 (10.9%) were potentially overtreated. Overtreatment of diabetes was more common among those who were over 75 years of age and enrolled in Medicaid (p < 0.001), and was less common among Hispanics (p = 0.009). Therapy was deintensified for 14% of overtreated diabetics. Appropriate deintensification of diabetic therapy was more common for patients with six or more chronic conditions, more outpatient visits, or living in urban areas; deintensification was less common for those over age 75. Only 6.9% of Medicare recipients with diabetes were potentially undertreated. Variables associated with overtreatment of diabetes differed from those associated with undertreatment.

Conclusions

Medicare recipients are more frequently overtreated than undertreated for diabetes. Medicare recipients who are overtreated for diabetes rarely have their regimens deintensified.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Treating diabetes requires balancing the risks of long-term harm from undertreatment with the short-term and long-term harm from potential overtreatment. At times, deintensification of therapy—removing treatments that were previously recommended1—is appropriate. The Choosing Wisely campaign, which has been promoted in multiple countries,2,3, – 4 focuses on reducing overtreatment. The American Geriatrics Society (AGS) specifically states that medications other than metformin should be avoided when an older patient’s hemoglobin A1c is less than 7.5%, because the risks of hypoglycemia are increased and the potential benefits of treatment are decreased for older adults with diabetes.5 , 6 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom offers a similar recommendation,7 as randomized trials have shown that the benefits of aggressive glycemic control begin only after at least 8 years of treatment,8,9,10, – 11 yet the harms of aggressive glycemic control—hypoglycemia, cardiovascular events, cognitive impairment, fractures, and death—can happen at any time.12,13,14,15, – 16 Several studies have reported that a significant proportion of adults with diabetes are potentially overtreated.17,18,19,20,21,22, – 23 A United States (US) Veterans Health Administration study found that only a small minority of overtreated diabetic patients received medication deintensification, causing unnecessary exposure to potentially harmful treatments.19

Prior work has identified a number of disparities in control of diabetes and its complications.24,25,26,27, – 28 However, most attention has focused on undertreatment of diabetes, and investigation of patient characteristics associated with overtreatment of diabetes20 or severe hypoglycemia21 has been limited. Therefore, we examined rates of overtreatment and deintensification of therapy for Medicare beneficiaries, and whether there were any disparities in these rates by race/ethnicity, dual eligibility, age, sex, rurality, or multimorbidity. To put these overtreatment findings into context, we compared the rates and patient characteristics associated with overtreatment and undertreatment of diabetes in the same cohort of patients.

METHODS

Data Source

We used Medicare claims from fee-for-service beneficiaries in 10 eastern US states (NY, NJ, MD, DE, VA, NC, SC, GA, FL, AL) from a data linkage project that has been described previously.29 We accessed the data through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse (CCW) Virtual Research Data Center. The data included Medicare Part D files, carrier Standard Analytic Files, Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse (CCW) summary files, and the corresponding denominator files from 2010 to 2011. The Medicare Part D files contain brand and generic prescription drug names, strength, days’ supply, quantity dispensed, and service date. The carrier files contain noninstitutional provider claims for services covered under Medicare Part B, including International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes, place of service, Current Procedural Terminology codes, and dates of service. Medicare claims for laboratory services were linked to actual outpatient laboratory values processed by a national laboratory vendor in 2011 for Medicare beneficiaries. The CCW summary file provides flags for 27 chronic diseases based on diagnoses in Parts A and B Medicare claims from 1999 onward.30 Denominator files include patient demographic characteristics, birth and death dates, and information about program eligibility and enrollment.

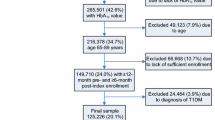

Study Cohort

We included older adults who met all the following criteria: enrolled in Medicare Parts A, B, and D between January 1, 2010, and December 30, 2011; had a diagnosis of diabetes in the CCW summary file in the 2 years before June 30, 2010; had at least one HbA1c lab result available between January 1, 2011, and June 30, 2011, and were 65 years or older at this HbA1c date; and were alive on December 31, 2011 (eFigure 1). If multiple HbA1c lab results existed for a patient, the first HbA1c lab was selected for analysis, and defined as the index date.

Medications

Diabetes medications were identified in the Medicare Part D files by searching, from 120 days before to 180 days after the index date, generic drug names for the following classes of medications: insulin, biguanides, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones, meglitinides, GLP-1 agonists, amylin analogs, DPP-4 inhibitors, and alpha-glycosidase inhibitors (see Appendix Table 5 for details). For patients on combination medications, we counted each component as a separate medication. Daily dose was calculated using medication strength, days’ supply, and quantity dispensed19 for all oral agents.

Outcomes

Patients were classified as potentially overtreated for diabetes if they had an index HbA1c value of less than 6.5% during the period from January through June 2011 and had filled any diabetes medications other than metformin in a pre-index medication regimen during the months leading up to this index HbA1c value. We chose this HbA1c threshold because it was substantially lower than the Choosing Wisely and AGS5 recommendations to avoid medications other than metformin when HbA1c values were less than 7.5%,31 and lower than the American Diabetes Association’s guidelines for glucose control for patients with diabetes.32 Patients were classified as potentially undertreated if their index HbA1c was greater than 9.0%, regardless of medication status, consistent with Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures since 1999.33 All others were classified as having acceptable treatment of their diabetes.

We defined medication deintensification among potentially overtreated older adults using a previously published method.19 Briefly, older adults on oral agents were defined as having had their regimens deintensified if they had medication fills with a lower dose than the index dose in the 1 to 180 days after the index date, or no refills of previously prescribed medications in the 22 to 180 days after the index date (see eFigure 1 in Sussman19 for an illustration). The index dose was defined as the medication dosage in the months leading up to the index HbA1c value used to define overtreatment, undertreatment, or neither. Medications filled in the 1–21 days after the date of the index dose were ignored for defining deintensification. We did this to account for blood draws or other visit-related work that occurs after the visit. Since HbA1c measurements are rarely repeated in under 3 months, this is unlikely to create any biases. Following prior work,19 older adults on insulin, pramlintide, or exenatide were defined as having deintensification if there were no medication refills in the 22 to 180 days after the index date. As the focus of this study was overtreatment and deintensification of therapy, we did not examine intensification of therapy for undertreated older adults, as many previous studies have examined this question.34

Study Variables

Covariates of interest obtained from the Medicare denominator files included baseline patient demographic characteristics, specifically age (65–70, 71–75, 76+), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, non-Hispanic black, other),23 Medicaid dual eligibility, indication for Medicare eligibility (age vs. disability), gender, and urban location.35 , 36 We derived urban location from rural-urban commuting area codes based on ZIP Code of residence. The number of chronic conditions (0–1, 2–3, 4–5, 6+) was constructed from the CCW chronic disease flags at end of year for 18 conditions (see Appendix Table 6 for details). From carrier physician claims, we obtained the number of outpatient visits for evaluation and management (E&M) visits in 2010 based on Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes 992.xx, 993.xx, and 994.xx.

Statistical Analysis

The associations between diabetes overtreatment and covariates of interest were summarized using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. We compared rates of overtreatment to undertreatment and adequate treatment by groups, using χ2 tests for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous variables. To assess the association between patient characteristics and three-level treatment outcome, we used a multinomial logistic regression with the reference category as adequate treatment that adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, Medicaid dual eligibility, indication for Medicare eligibility (age vs. disability), gender, multimorbidity, number of outpatient visits, and urban location (Table 1).35 , 36 To account for multiple comparisons, we report 99% confidence intervals and used a two-tailed α = 0.01 to establish the statistical significance of tests for all analyses.

Among potentially overtreated individuals, we examined variables associated with treatment deintensification using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. To test for differences between those who did and did not receive deintensification of treatment, we used χ2 tests for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous variables. We then examined whether deintensification differed based on race/ethnicity, dual eligibility, older age, sex, rurality (urban/rural), or multimorbidity, using multivariable logistic regression. Results are presented in both tabular and graphical form. The institutional review board of the Duke University Health System approved the study, and analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

We identified 78,972 older adults who had been diagnosed with diabetes and met the inclusion criteria (Appendix figure 1), of whom 10.8% (n = 8560) were potentially overtreated and 6.9% (n = 5487) were potentially undertreated for diabetes. Overtreatment was more prevalent than undertreatment in all subgroups examined except those with one or fewer comorbidity (Table 2). Rates of overtreatment were highest among those who were dual eligible for Medicaid (13.4%) and those over 75 years of age (12.1%), and ranged from 11.1% for non-Hispanic blacks to 9.6% for those of “other” race/ethnicity.

After adjustment, overtreatment remained more likely for those dually enrolled in Medicaid and those over 75 years of age, while overtreatment was less likely for Hispanic beneficiaries and those in urban areas (Table 2). The variables associated with overtreatment of diabetes differed considerably from those associated with undertreatment (Table 2).

Of the 8560 older adults who were potentially overtreated (Table 3), 13.9% (n = 1187 of 8560) received treatment deintensification within 180 days following the index HbA1c. Rates of deintensification were highest for adults aged 65–70 (15.1%) and Hispanic patients (Table 4). Treatment deintensification increased with the number of chronic conditions.

In adjusted analysis, deintensification of diabetes therapy was more likely for those with 6 or more chronic conditions (adj. OR = 1.57, 99% confidence interval [CI]: 1.13–2.16), in urban areas (adj. OR = 1.17, 99% CI: 1.01–1.36) or with more outpatient visits (adj. OR = 1.04, 99% CI: 1.00–1.08). Deintensification was less likely for those over 75 years of age (adj. OR = 0.78, 99% CI: 0.67–0.90).

DISCUSSION

We found that overtreatment was more common than undertreatment of diabetes for Medicare beneficiaries in 2011. Among those overtreated, only about 14% received treatment deintensification, which is lower than rates of deintensification reported in prior studies of veterans in 201219 and privately insured individuals in 2013.21 As the AGS began recommending less aggressive treatment of diabetes in 2013, current rates of overtreatment may be somewhat lower than what we report here.

We found that overtreatment of diabetes for Medicare patients was associated with age over 75 and Hispanic race/ethnicity, which is consistent with prior studies of overtreatment of diabetes.20 , 21 Interestingly, older adults dually enrolled in Medicaid and Medicare were both more likely to be overtreated and more likely to be undertreated for diabetes than individuals without dual enrollment, possibly because this is a very heterogeneous group with highly variable diabetes control and a greater diversity of comorbid conditions. Future work is needed to determine whether there are distinct subgroups of dual-eligible individuals with diabetes who might benefit from specific approaches to diabetes management.

We found deintensification of diabetes therapy to be more common for Medicare beneficiaries with six or more chronic conditions, more outpatient visits, or living in urban areas, and less likely for those over age 75. It is troubling that the oldest Medicare beneficiaries were more likely to be overtreated and less likely to have their medication regimens deintensified, because these older adults are least likely to benefit from tight glycemic control and most likely to be harmed. It is encouraging that those with multiple chronic conditions were more likely to receive deintensification, because they often have complex medication regimens, and prior studies have shown that risk for hypoglycemia increases with age, comorbidity burden, and polypharmacy.13

Despite the relative lack of patient characteristics associated with overtreatment and deintensification, we found substantial disparities in potential undertreatment of diabetes among Medicare beneficiaries, consistent with previous findings.24,25,26,27, – 28 These disparities have long plagued American healthcare. This is the first study to examine overtreatment and deintensification in a Medicare population and to examine rates of potential overtreatment and undertreatment in the same cohort. Nonetheless, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, we were unable to separately examine age-eligible and disability-eligible older adults, since all adults were 65 years of age or older. Second, we stratified older adults by demographic characteristics and comorbidity burden, but did not stratify them by health status defined by activities of daily living18 or by life expectancy19 as in prior work. Similarly, we did not examine subgroup differences via interaction terms, which would merit consideration in future work with larger samples. Third, the reasons for a lack of deintensification among those potentially overtreated for diabetes are unknown. It is possible that clinicians did not recommended a change in regimen, and it is also possible that deintensification was recommended but patients preferred to remain on their existing regimen. Fourth, glycemic control was based upon a single cross-sectional measurement in 2011, so it is unknown whether older adults’ control was stable or changing prior to the index value we studied. Fifth, the results may not generalize to older adults outside of these 10 eastern states or those enrolled in Medicare Advantage. Finally, we were not able to examine whether potential overtreatment or lack of deintensification was associated with clinically relevant adverse outcomes.

Optimizing glucose control is clinically difficult, but it is a public health imperative. Major trials have shown that aggressive diabetes control has both significant benefits for younger, healthy patients and substantial risks for older patients and those with comorbidities.8,9,10, – 11 Recent clinical practice guidelines acknowledge that these risks must be addressed for older adults in particular.5 , 7 , 37 However, this guidance was not universal in 2011. Therefore, our findings on the prevalence of overtreatment of Medicare beneficiaries in 2011 may in part reflect the fact that clinicians had not adapted to recent clinical guidelines for diabetes management that relaxed glycemic control targets for older adults with multiple chronic conditions, limited life expectancy, diabetic complications, or functional impairment.5 Future studies should examine whether rates of overtreatment and deintensification of diabetes regimens have changed over the last 6 years, and whether the disparities observed here have narrowed.

The management of diabetes in the presence of comorbidities must also be carefully considered, because comorbidity may alter medication choices. Guidelines from the American Diabetes Association have long recommended less intensive treatment for people with “important comorbidities,” and modeling studies have long shown that factors in addition to HbA1c should influence the overall net benefit of intensive treatment.38 However, this study and other work in different settings and countries has shown that comorbidity has a minimal impact on diabetes treatment intensity as measured by the A1c achieved. Additional work is needed to understand whether deintensification of diabetic therapy affects older adults differently depending on their number of comorbid conditions, because so little is yet known in this emerging area of research and clinical practice.

For decades, diabetes guidelines and performance measures have focused only on reducing the undertreatment of diabetes. Even now, while guidelines mention more relaxed HbA1c targets for appropriate patients, there are no algorithms for deintensifying treatments. The focus on undertreatment has resulted in dramatic improvements in glycemic control, on average, but has apparently also encouraged overtreatment. In the current era, effective treatment of diabetes requires a major shift in approach toward greater personalization of treatment based on individual potential risk and benefit. Our study points the way for identifying not only those patients who may benefit from more intensive treatment, but also those who may need deintensification. By focusing at both the overtreatment and undertreatment ends of the diabetes quality spectrum, we can best begin to truly improve the quality of diabetes care, ensuring that patients get needed care while avoiding unnecessary potential harm.

References

Kerr EA, Hofer TP. Deintensification of Routine Medical Services: The Next Frontier for Improving Care Quality. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):978-980.

Canada Choosing Wisely website. http://www.choosingwiselycanada.org. Accessed 5 March 2017.

UK Choosing Wisely website. http://www.choosingwisely.co.uk/. Accessed 5 March 2017.

Levinson W, Kallewaard M, Bhatia RS, et al. 'Choosing Wisely': a growing international campaign. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24(2):167-174.

AGS Choosing Wisely Workgroup. American Geriatrics Society identifies five things that healthcare providers and patients should question. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61(4):622-631.

American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Care of Older Adults with Diabetes Mellitus, Moreno G, Mangione CM, Kimbro L, Vaisberg E. Guidelines abstracted from the American Geriatrics Society Guidelines for Improving the Care of Older Adults with Diabetes Mellitus: 2013 update. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61(11):2020-2026.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Type 2 diabetes in adults: management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28/chapter/1-Recommendations. Accessed 1 December 2018.

Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet. 1998;352(9131):854–865.

Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet. 1998;352(9131):837–853.

ADVANCE Collaborative Group, Patel A, MacMahon S, et al. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;358(24):2560-2572.

Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Study Group, Gerstein HC, Miller ME, et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;358(24):2545-2559.

Montori VM, Fernandez-Balsells M. Glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: time for an evidence-based about-face? Ann Intern Med 2009;150(11):803-808.

Lipska KJ, Krumholz H, Soones T, Lee SJ. Polypharmacy in the Aging Patient: A Review of Glycemic Control in Older Adults With Type 2 Diabetes. JAMA. 2016;315(10):1034-1045.

Shorr RI, Ray WA, Daugherty JR, Griffin MR. Incidence and risk factors for serious hypoglycemia in older persons using insulin or sulfonylureas. Arch Intern Med 1997;157(15):1681-1686.

McCoy RG, Van Houten HK, Ziegenfuss JY, Shah ND, Wermers RA, Smith SA. Increased mortality of patients with diabetes reporting severe hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care 2012;35(9):1897-1901.

McCoy RG, Van Houten HK, Ziegenfuss JY, Shah ND, Wermers RA, Smith SA. Self-report of hypoglycemia and health-related quality of life in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Endocr Pract 2013;19(5):792-799.

Tseng CL, Soroka O, Maney M, Aron DC, Pogach LM. Assessing potential glycemic overtreatment in persons at hypoglycemic risk. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174(2):259-268.

Lipska KJ, Ross JS, Miao Y, Shah ND, Lee SJ, Steinman MA. Potential overtreatment of diabetes mellitus in older adults with tight glycemic control. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(3):356-362.

Sussman JB, Kerr EA, Saini SD, et al. Rates of Deintensification of Blood Pressure and Glycemic Medication Treatment Based on Levels of Control and Life Expectancy in Older Patients With Diabetes Mellitus. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(12):1942-1949.

Thorpe CT, Gellad WF, Good CB, et al. Tight glycemic control and use of hypoglycemic medications in older veterans with type 2 diabetes and comorbid dementia. Diabetes Care Apr 2015;38(4):588-595.

McCoy RG, Lipska KJ, Yao X, Ross JS, Montori VM, Shah ND. Intensive Treatment and Severe Hypoglycemia Among Adults With Type 2 Diabetes. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176(7):969-978.

Muller N, Khunti K, Kuss O, et al. Is there evidence of potential overtreatment of glycaemia in elderly people with type 2 diabetes? Data from the GUIDANCE study. Acta Diabetol Feb 2017;54(2):209-214.

Penfornis A, Fiquet B, Blickle JF, Dejager S. Potential glycemic overtreatment in patients >/=75 years with type 2 diabetes mellitus and renal disease: experience from the observational OREDIA study. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2015;8:303-313.

Ayanian JZ, Landon BE, Newhouse JP, Zaslavsky AM. Racial and ethnic disparities among enrollees in Medicare Advantage plans. N Engl J Med 2014;371(24):2288-2297.

Bonds DE, Zaccaro DJ, Karter AJ, Selby JV, Saad M, Goff DC, Jr. Ethnic and racial differences in diabetes care: The Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Diabetes Care 2003;26(4):1040-1046.

Heisler M, Smith DM, Hayward RA, Krein SL, Kerr EA. Racial disparities in diabetes care processes, outcomes, and treatment intensity. Med Care 2003;41(11):1221-1232.

Karter AJ, Ferrara A, Liu JY, Moffet HH, Ackerson LM, Selby JV. Ethnic disparities in diabetic complications in an insured population. JAMA. 2002;287(19):2519-2527.

Kirk JK, D'Agostino RB, Jr., Bell RA, et al. Disparities in HbA1c levels between African-American and non-Hispanic white adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2006;29(9):2130-2136.

Hammill BG, Curtis LH, Qualls LG, Hastings SN, Wang V, Maciejewski ML. Linkage of Laboratory Results to Medicare Fee-for-Service Claims. Med Care 2015;53(11):974-979.

Gorina Y, Kramarow EA. Identifying chronic conditions in Medicare claims data: evaluating the Chronic Condition Data Warehouse algorithm. Health Serv Res 2011;46(5):1610-1627.

Huang ES. Potential Overtreatment of Older, Complex Adults With Diabetes. JAMA. 2015;314(12):1280-1281.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2011. Diabetes Care 2011;34 Suppl 1:S11-61.

National Committee for Quality Assurance. HEDIS 1999, Volume 2: Technical Specifications for Health Plans. Washington DC: National Committee for Quality Assurance; 1999.

Ajmera M, Raval A, Zhou S, et al. A Real-World Observational Study of Time to Treatment Intensification Among Elderly Patients with Inadequately Controlled Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2015;21(12):1184-1193.

US Department of Agriculture ERS. Rural urban commuting area codes. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes/. Accessed 31 March 2011.

Center WWAMI Rural Health Research Center. RUCA data: using RUCA data. http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca-data.php. Accessed 31 March 2011.

Kirkman MS, Briscoe VJ, Clark N, et al. Diabetes in older adults. Diabetes Care 2012;35(12):2650-2664.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2016 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. Clin Diabetes 2016;34(1):3-21.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editor and two reviewers for helpful comments. The research in this article was supported by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services under contract number HHSM-500-2014-00442G with the National Committee for Quality Assurance. This work was also supported by the Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development Service, Department of Veterans Affairs, and Dr. Maciejewski was also supported by a Research Career Scientist award from the Department of Veterans Affairs (RCS 10-391). The National Committee for Quality Assurance and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services provided feedback on interpretation of the data when the manuscript was reviewed and approved, but had no role in the design, conduct, collection, management, or analysis of the data. This work was presented at the 2017 AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Duke University, the National Committee for Quality Assurance, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, or the US Department of Health and Human Services. We acknowledge helpful review by Sarah Scholle, Michael Barr, and Mary Barton at the National Committee for Quality Assurance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Maciejewski has received institutional grants from the VA HSR&D, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and the National Cancer Institute, and an institutional contract from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; and reports ownership of Amgen stock due to his spouse’s employment. Dr. Maciejewski received honoraria for speaking at a workshop held at the University of Alabama-Birmingham. Dr. Sussman has received research support from VA HSR&D in the form of a career development award. Dr. Curtis has received research support from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Boston Scientific, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GE Healthcare, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Medtronic, Merck, and Novartis. Dr. Kerr has received research support from VA HSR&D to examine deintensification of medical services. All other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maciejewski, M.L., Mi, X., Sussman, J. et al. Overtreatment and Deintensification of Diabetic Therapy among Medicare Beneficiaries. J GEN INTERN MED 33, 34–41 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4167-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4167-y