ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

One potential approach to reducing health disparities among minorities is through the promotion of shared decision making (SDM). The most commonly studied SDM intervention is the decision aid (DA). While DAs have been extensively studied, we know relatively little about their use in minority populations. We conducted a systematic review to characterize the application and effectiveness of DAs in racial, ethnic, sexual, and gender minorities.

METHODS

We searched PubMed for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating DAs between 2004 and 2013. We included trials that enrolled adults (> 18 years of age) with > 50 % representation by minority patients. Four reviewers independently assessed 597 initially identified articles, and those with inconclusive results were discussed to consensus. We abstracted decision quality, patient-doctor communication, and clinical treatment decision outcomes. Results were considered significantly modified by the DA if the study reported p < 0.05.

RESULTS

We reviewed 18 RCTs of DA interventions in minority populations. The majority of interventions (78 %) addressed cancer screening. The most common mode of delivery for the DAs was personal counseling (46 %), followed by multi-media (29 %), and print materials (25 %). Most of the trials studied racial (78 %) or ethnic (17 %) minorities with only one trial focused on sexual minorities and none on gender minorities. Ten studies tailored their interventions for their minority populations. Comparing intervention vs. control, decision quality outcomes improved in six out of eight studies and patient–doctor communication improved in six out of seven studies. Of the 15 studies that reported on clinical decisions, eight demonstrated significant changes in decisions with DAs.

DISCUSSION

DAs have been effective in improving patient-doctor communication and decision quality outcomes in minority populations and could help address health disparities. However, the existing literature is almost non-existent for sexual and gender minorities and has not included the full breadth of clinical decisions that affect minority populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Health disparities negatively impact the lives of many minorities, but especially racial, ethnic, sexual and gender minorities. Racial and ethnic minorities have higher rates of chronic diseases, such as cancer, cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Moreover, when they develop these conditions, they suffer higher mortality rates than their white counterparts.1 Similarly, sexual and gender minorities suffer from higher rates of physical and mental illness than majority populations. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals have higher rates of mood anxiety disorders and suicidal ideation than majority populations.2 Racial, ethnic, sexual, and gender minorities’ health care has been hindered by the failure to include these patients in clinical research that has left health care providers with a modest evidence base and an absence of implementation strategies.

Shared decision making (SDM) is one important potential conceptual approach to alleviating health disparities. SDM is the practice of facilitating patient–physician discussions to determine health care plans. One of the most widely disseminated conceptual models of SDM is grounded in three pillars: 1) information-sharing, 2) deliberation and/or physician recommendation and 3) decision making.3,4 SDM has the potential to increase patient satisfaction, align the selection of treatments with patients’ preferences, increase adherence to therapies, and improve clinical outcomes.5–8

While SDM has great promise, patients of minority backgrounds experience SDM less often than non-minority populations.9–11 Minority populations may also have alternative conceptions and definitions of SDM that raise questions about the effectiveness of this model of care. For example, Peek et al. explored SDM among African American patients and discovered that information sharing preferences differed significantly from the traditional SDM model among these patients.12 In addition to differences in preferences for information sharing, some minority populations may have higher rates of low literacy that may require significant modification of material designed to engage patients.7,13

The most commonly studied intervention to facilitate SDM in clinical practice is the decision aid (DA). DAs are educational tools designed to encourage patients to participate in medical decisions by displaying the benefits and harms of treatment options and by eliciting patient preferences, particularly for decisions with scientific uncertainty.14 Over the past several decades, the field has matured significantly. There are now over 115 DAs described in the literature and established best practices for evaluating DAs.14

Despite the extensive DA literature, we know little about how frequently minority populations experience DAs or how much they have been tailored to their populations’ specific needs (e.g., low literacy). We reviewed existing randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that examine DAs with under-represented minority populations. By conducting this review, we hoped to identify the gaps in knowledge and research opportunities about the best practices for DAs within minority patient populations. The following systematic review aimed to answer: 1) what types of DA interventions are being tested within minority populations, 2) what conditions do these tested interventions address, and 3) what DA interventions have changed decision quality, patient–doctor communication, and clinical decision outcomes within minority populations?

METHODS

We conducted our systematic review by: 1) defining our key research questions, 2) identifying search terms and literature search, 3) reviewing abstracts and screening for inclusion/exclusion criteria, 4) abstracting data, and 5) analyzing data. This systematic review adhered closely to the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA).15

Data Search

Our primary research question was: what types of DA interventions have been tested in minority populations; specifically, racial, ethnic, sexual and gender minority individuals in the past decade? We also sought to discover what conditions these interventions addressed and in which minority populations these interventions were tested. We additionally explored whether DAs were being tailored for minority populations.

We searched PubMed from 1 January 2004 to 31 December 2013 for RCTs of DAs conducted in minority populations. Search terms were developed and tested with assistance from librarians to ensure a comprehensive and inclusive search. We used pre-specified and tested Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and keywords to identify RCTs evaluating DAs and SDM tools (e.g., Decision Making, Decision Theory) within racial, ethnic, sexual, and gender minority populations (e.g., "Minority Groups", Homosexuality, Transgendered Persons) (Table 1).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Our search included English RCTs that evaluated DAs within minority populations. Based on established models of SDM and DAs,14 we included studies with an intervention that included 1) information sharing or education and 2) risks and benefits of treatment options, to enable SDM. Studies in which < 50 % of the participants identified as part of a racial (African American, Asian American), ethnic (Hispanic/Latino), sexual (LGB) or gender (Transgender) minority were excluded.12,16 Studies with individuals younger than 18 years old were excluded.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Four raters independently reviewed a randomly selected, 10 % sample of articles from our search and identified articles for inclusion. The inter-rater reliability of the raters was 0.83. The remaining articles were divided among the raters and assessed for eligibility. Articles with inconclusive results were discussed to consensus among the raters. Finally, we performed a hand-search of the 2014 Cochrane Collaboration review and found six DA interventions that met our criteria.14 We found that only one article was not previously discovered in our search of PubMed.

Outcomes of Interest

We focused our review on three sets of outcomes that are relevant to SDM. We first reviewed studies with results on decision quality outcomes. This outcome category included decisional conflict, satisfaction with decisions, and worry or anxiety regarding a decision. Second, we examined the impact of DAs on patient–doctor communication. Communication is one pillar of SDM, and includes the patient stating their intent or if they actually reported having a discussion with their provider about their treatment decision. We also included quality of communication in this outcome. Our third outcome was clinical treatment decisions, and included all outcomes relating to the treatment decision under investigation. This outcome category included the willingness to undergo treatment, readiness for treatment, intent to complete treatment and completion of treatment.

When assessing outcomes, we classified interventions as effective if decision quality outcomes improved (e.g., less decisional conflict, less worry), if communication outcomes improved (e.g., more communication, greater quality of communication), and if treatment decisions were moved by the intervention. We required statistical significance at p < 0.05 to be considered a positive result. For all three outcomes, we examined whether culturally tailored interventions were more effective compared to interventions that were not culturally tailored.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

The included articles were divided among the reviewers, and data were abstracted from full text articles using an adapted abstraction form from Zaza and colleagues.17 For included studies, we abstracted data on population characteristics, intervention characteristics, intervention outcomes, tailoring of interventions, and feasibility considerations. After data were abstracted, two reviewers checked the content for consistency. In addition, the research team scored each included study for quality by using a tool based on the Downs and Black (1998) guidelines (28 point scale: 0 worst, 28 best). One article was removed from inclusion for failure to meet the minority inclusion requirement, and two articles were removed for failure to qualify as a DA. Data were synthesized and analyzed by using tables and primary research questions to compare the included studies. The details of the data abstraction forms were entered into tables and the main findings were contrasted and tabulated.

RESULTS

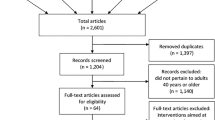

Our search identified 597 abstracts for screening and review. After abstract, title and full text review, we included 22 articles for data abstraction and analysis. During data abstraction, we discovered three articles could not be included due to exclusion criteria. This resulted in inclusion of 19 articles for data analysis (Fig. 1), (Online Appendix). The majority of publications were excluded for failure to meet multiple inclusion criteria. The most common reason for excluding a study was that the intervention was not a DA. Five articles were excluded because their study populations did not meet the > 50 % minority criteria. This review represents data on the reports of RCTs that used decision support tools in minority populations (Table 2).18–36 Two of the articles described different outcomes from one RCT.31,32 Thus, we considered these two papers one intervention, resulting in a total of 18 interventions with data. The results describe select studies from our review that highlight the types of health conditions, populations studied, DA type and delivery mode, and cultural tailoring used.

Decision Aid Type and Delivery

Many of the trials attempted to test their SDM intervention through multiple modalities (Table 3). Eight studies utilized more than one method to deliver their intervention (e.g., print and phone counseling), and the remaining ten studies used one method each. Counseling or interviewing was the most common mode of delivery for DAs (n = 13); however, several types of counseling were utilized: one-on-one counseling or interviewing (n = 6), group counseling (n = 4), and telephone (n = 3). The second most common form of DA was multi-media delivery. These varied from DVDs, computer kiosks with touch screens, and desktop computers with interactive displays. This type of DA was most often self-guided (n = 7); however, one study did use an assisted multi-media DA.

One example of an intervention that used multiple DA delivery modalities was the study by Glanz et al. (quality score 19). The authors used counseling, print materials, and phone calls to deliver decision support.23 Counseling sessions were led by a nurse or health educator, and were tailored to the diverse and multiethnic population of Hawaii. The study aimed to increase colorectal screening among children and siblings of CRC patients. Using an attention control design, the study found that adherence to screening guidelines among intervention subjects compared to controls was statistically significant (p = 0.03) when measured at the 4-month follow-up. The intervention group showed a 13 percent increase in adherence at 4 months, which was reduced to 11 percent at 12-month follow-up (p = 0.09).

Health Conditions

Of the 18 studies included in this review, the majority (n = 14) focused on cancer prevention through screening or other means. The type of cancer evaluated among these 14 studies was limited to prostate, colorectal (CRC), and breast cancer. The remaining four trials evaluated DAs in three unique health conditions: kidney disease (end-stage renal disease and chronic kidney disease)33,34, osteoarthritis25, and healthy lifestyle change.22

The most commonly studied medical condition in our review was prostate cancer. Prostate cancer screening is an area surrounded by clinical uncertainty and is sensitive to patient preferences. In one of the six prostate cancer studies we reviewed, Lepore and colleagues tested a DA in African American men aged 45–70 (quality score 17). We highlight this study because it reported the largest number of SDM outcomes among the prostate cancer DAs. The purpose of this intervention was to provide information and exercises to enable men to make an informed decision about prostate cancer screening that would be consistent with their values.27 The DA consisted of a printed pamphlet with pros and cons of prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing, and was followed by a phone call or in person counseling session. The study used an attention control design where control subjects received phone calls about fruits and vegetables. The education portion of the counseling sessions was tailored based on the patient’s knowledge. When compared to the control arm, the intervention arm showed increased uptake in PSA testing, and 8.3 % of controls versus 15.8 % of intervention stated they had a visit to discuss prostate cancer with their provider (p < 0.001). The intervention group reported lower decisional conflict than the control group (p < 0.014). Both 81 % of control and intervention patients said they planned on a prostate test at the post-test (not significant).

Population Characteristics

Seventeen studies focused on racial or ethnic minorities. Eight of the interventions studied African Americans, two studied Hispanic or Latino populations, one studied a predominately Asian population, and the remaining six studies consisted of diverse minority populations (three majority African American, two majority Asian, and one majority Hispanic). Of the 18 studies we reviewed, one studied a DA in a sexual minority population.

In the only study focused on sexual minorities, Bowen and colleagues tested the effects of breast cancer risk counseling on sexual minority women (SMW) (quality score 17).18 One hundred and fifty self-identified bisexual and lesbian women participated in the study. The study utilized four group counseling sessions of five to eight women with a trained SMW health counselor to cover risk assessment, education, breast cancer screening, stress management, and social support. Three options for breast cancer screening were covered: mammography, clinical breast exam, and breast self-exam. The study used a delayed intervention control group to study the effects of the program. This program had a positive effect; perceived risk (0–100 scale, control = 33, intervention = 17), cancer worry (4–16 scale, control = 6.2, intervention = 5.2) and mental health scores (0–100 scale, control = 74.8, intervention = 80.3) improved over 24 months for both groups, but the improvement was greater for the intervention group (p < 0.01). Rates of breast self-examination, increasing by 17 % to 52 % (p < 0.01), and mammogram, increasing from 12 % to 87 % (p < 0.05), increased for participants that received the intervention, while it remained stagnant for the control group.

Tailoring of Intervention for Population of Interest

The extent of cultural tailoring varied across interventions. We found that ten of the studies used some form of tailoring to customize their interventions for their racial, ethnic, or sexual minority populations. The remaining eight studies did not report an attempt to culturally tailor their interventions. However, three of the non-culturally tailored studies did tailor their intervention for other characteristics of their population, such as low or mixed-literacy.

An excellent example of cultural tailoring was found in the study by Makoul et al. Investigators customized their intervention after extensive interviews with Latino patients (quality score 14).28 The final intervention was an interactive multi-media format that was accompanied by promotores (lay Hispanic/Latino community health workers) who helped participants use the DA.37 The DA included education about CRC, screening options and risks for CRC, and explored how communication with the provider could aid in SDM. The results of the study were positive; they indicated both an increase to 90 % in patients’ intent to discuss CRC screening with their providers (no p value reported) and an increased willingness to consider all three screening options—24 % increase for fecal occult blood test, 24 % increase for flexible sigmoidoscopy, 19.6 % increase in colonoscopy (p < 0.001).

Outcomes

The majority of studies showed improvement in the intervention vs. control arm in their reported outcomes (Table 2). Out of the seven studies that tested and reported on communication, six of them showed statistically significant improvement. There were eight studies that tested and reported on decision quality outcomes (e.g., decisional conflict), and six of those studies showed improvement in the quality of the decisions of their subjects. The most frequently reported outcome was on clinical decisions, with 15 studies reporting results. Eight of these studies showed significant changes in clinical decision behavior (e.g., screening test uptake).

To compare interventions that did and did not culturally tailor, we focused on the clinical decision outcome, which was the most frequently reported (n = 15). Six out of nine culturally tailored interventions reported significant changes in clinical decisions, while only two out of six non-tailored interventions reported significant changes.

DISCUSSION

In health policy circles, SDM has been promoted as a means of improving quality of care and was included as a provision within the Affordable Care Act to support the development and use of DAs.38 In light of new policies, it is more important than ever to understand the evidence regarding the effectiveness of interventions designed to encourage SDM. Encouraging SDM is a primary component of DAs, which do have a robust evidence base that developed over the past several decades. One concern regarding DAs is that their impact on minority populations and health disparities has received almost no attention. In this systematic review, we conducted one of the first focused efforts to characterize the DA literature in minority populations. We found a small body of evidence (18 studies) illustrating the effectiveness of DAs in minority populations. Considering the broader DA literature, this suggests that only 14 % of DA trials (18/129) have had significant minority representation.14

Despite the small size of the existing evidence, we did find that the pattern of effectiveness of DAs in racial, ethnic, and sexual minority populations mirrors findings from the prior literature regarding DAs. In the studies included in this review, DAs consistently produced improved decision quality for patients and improved patient–doctor communication. A narrow majority of DAs moved treatment decisions. The confirmation that DAs can be effective tools within minority populations is an important finding that may have broader, positive implications for the alleviation of health disparities within racial, ethnic, sex and gender-based minorities.2 In a sensitivity analysis, we also found that interventions that were culturally tailored appeared to have a larger impact on clinical decisions than those that did not tailor. This finding should be viewed cautiously, given the small sample of studies available.

While the overall findings are positive, the minority DA literature is extremely limited in terms of the range of study populations that have been evaluated. The populations that have been studied are primarily ethnic/racial minorities, with only one study focused on sexual minority (self-identified lesbian and bisexual) women and none in gender minorities. No studies focused on populations that are both racial and sexual minorities. Peek et al. conducted a systematic review of SDM at the intersection between African Americans and LGBT patients and found only three publications, so it is not surprising that this intersectionality does not exist in the DA literature.39

Another important limitation of the literature is that the range of clinical topics in these interventions does not reflect the wide range of medical needs of minority populations. The vast majority of interventions we found focused on cancer screening. Historically, DAs have been limited to the study of single event decisions and have not focused on highly prevalent chronic conditions that require recurrent medical decisions.40 DAs could be expanded into a diverse range of clinical topics that are relevant in the lives of minority patients. For example, among sexual minorities and gender minorities there are a number of clinical topics that have a cloud of uncertainty and would benefit from an SDM approach. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a new treatment that has great potential to lower the risk of HIV, but may have the burden of pill taking and unanticipated long-term side effects. The decision to use PrEP would benefit from understanding the preferences of individual patients. Another important area that may fit this paradigm are decisions to undergo gender-affirming surgeries or hormone therapies. Decisions regarding the medical and surgical options for gender transition should all be informed by patient preferences. DAs in these clinical areas might ensure that all relevant information regarding the risks and benefits of treatment options are fully considered and that the preferences of individual patients are registered by the clinician. Many of the studies we excluded were interventions designed to modify health behaviors without an SDM framework. Most of these studies did not offer patients an evaluation of the treatment options or elicit patient preference. For some medical situations (e.g., quarantine in the face of an infectious epidemic), the SDM model may not be appropriate. However, we believe that almost all decisions can be viewed through the lens of SDM and can be a way to improve treatment adherence.41

Another opportunity for promoting SDM for minority patients is to consider making changes in the clinical environment.42 The reality is that DAs cannot be designed for every micro-decision that occurs in the life of a patient and it may be potentially more important to create a culture of SDM. DeMeester and colleagues explore the drivers and mechanisms required to impact care; the model contains six drivers: workflows, health information technology, organizational structure and culture, resources and clinic environment, training and education, and incentives and disincentives. These drivers work through four mechanisms that can impact care: continuity and coordination, the ease of SDM, knowledge and skills, and attitudes and beliefs. It is possible that even the best designed DAs and clinical interventions will not affect change unless these drivers and mechanisms are evaluated and changed to accommodate minority populations.

This review of DAs in minority populations is limited in that our sample size was very small, and it is difficult to provide recommendations for specific sub-populations based upon our results. However, this limitation highlights one of our primary findings: that more DAs need to be studied in minority populations.

In conclusion, DAs in minority populations have been similarly efficacious as DAs in majority populations. However, there is currently a lack of research on DAs in racial, ethnic, sexual, and gender minority populations and a lack of diversity of tools and study participants within existing literature. The lack of DA research in minority populations parallels a general lack of SDM in actual clinical practice for minority patients.9,10,43,44 The need to expand DA research experiences within minority populations is now more important than ever, given the recent adoption and promotion of SDM by policymakers. This will help to ensure that DAs are optimally designed for the language, culture, and medical needs of all minority patients.

REFERENCES

Nelson A. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(8):666–8.

Institute of Medicine Commitee on Lesbian G. Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities, The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington: National Academies Press; 2011.

Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49(5):651–61.

Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(5):681–92.

Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152(9):1423.

Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE Jr, Yano EM, Frank HJ. Patients' participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3(5):448–57.

Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361–7.

Barry MJ. Shared decision making: informing and involving patients to do the right thing in health care. J Ambul Care Manag. 2012;35(2):90–8.

Peek ME, Tang H, Cargill A, Chin MH. Are there racial differences in patients' shared decision-making preferences and behaviors among patients with diabetes? Med Decis Making : an Intern J Soc Med Decis Making. 2011;31(3):422–31.

Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, et al. Race, gender, and partnership in the patient–physician relationship. JAMA. 1999;282(6):583–9.

Levinson W, Hudak PL, Feldman JJ, et al. "It's not what you say …": racial disparities in communication between orthopedic surgeons and patients. Med Care. 2008;46(4):410–6.

Peek ME, Quinn MT, Gorawara-Bhat R, Odoms-Young A, Wilson SC, Chin MH. How is shared decision-making defined among African-Americans with diabetes? Patient Educ Couns. 2008;72(3):450–8.

Bekker HL, Winterbottom AE, Butow P, et al. Do personal stories make patient decision aids more effective? A critical review of theory and evidence. BMC Med Inform Decis Making. 2013;13(Suppl 2):S9.

Stacey D, Legare F, Col NF, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD001431.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9. W264.

Fuentes D, Aranda MP. Depression interventions among racial and ethnic minority older adults: a systematic review across 20 years. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr: Off J Am Assoc Geriatric Psychiatr. 2012;20(11):915–31.

Zaza S, Wright-De Aguero LK, Briss PA, et al. Data collection instrument and procedure for systematic reviews in the Guide to Community Preventive Services. Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1 Suppl):44–74.

Bowen DJ, Powers D, Greenlee H. Effects of breast cancer risk counseling for sexual minority women. Health Care Women Int. 2006;27(1):59–74.

Chan EC, McFall SL, Byrd TL, et al. A community-based intervention to promote informed decision making for prostate cancer screening among Hispanic American men changed knowledge and role preferences: a cluster RCT. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84(2):e44–51.

Christy SM, Perkins SM, Tong Y, et al. Promoting colorectal cancer screening discussion: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(4):325–9.

Ellison GL, Weinrich SP, Lou M, Xu H, Powell IJ, Baquet CR. A randomized trial comparing web-based decision aids on prostate cancer knowledge for African-American men. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(10):1139–45.

Geller KS, Mendoza ID, Timbobolan J, Montjoy HL, Nigg CR. The decisional balance sheet to promote healthy behavior among ethnically diverse older adults. Public Health Nurs. 2012;29(3):241–6.

Glanz K, Steffen AD, Taglialatela LA. Effects of colon cancer risk counseling for first-degree relatives. Cancer Epidemiol, Biomarkers Prev : a Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res American Society of Preventive Oncol. 2007;16(7):1485–91.

Holt CL, Wynn TA, Litaker MS, Southward P, Jeames S, Schulz E. A comparison of a spiritually based and non-spiritually based educational intervention for informed decision making for prostate cancer screening among church-attending African-American men. Urol Nurs. 2009;29(4):249–58.

Ibrahim SA, Hanusa BH, Hannon MJ, Kresevic D, Long J, Kent KC. Willingness and access to joint replacement among African American patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, controlled intervention. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(5):1253–61.

Lam WW, Chan M, Or A, Kwong A, Suen D, Fielding R. Reducing treatment decision conflict difficulties in breast cancer surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2013;31(23):2879–85.

Lepore SJ, Wolf RL, Basch CE, et al. Informed decision making about prostate cancer testing in predominantly immigrant black men: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med: a Publ Soc Behav Med. 2012;44(3):320–30.

Makoul G, Cameron KA, Baker DW, Francis L, Scholtens D, Wolf MS. A multimedia patient education program on colorectal cancer screening increases knowledge and willingness to consider screening among Hispanic/Latino patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76(2):220–6.

Miller DP Jr, Spangler JG, Case LD, Goff DC Jr, Singh S, Pignone MP. Effectiveness of a web-based colorectal cancer screening patient decision aid: a randomized controlled trial in a mixed-literacy population. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(6):608–15.

Myers RE, Daskalakis C, Cocroft J, et al. Preparing African-American men in community primary care practices to decide whether or not to have prostate cancer screening. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(8):1143–54.

Schroy PC 3rd, Emmons K, Peters E, et al. The impact of a novel computer-based decision aid on shared decision making for colorectal cancer screening: a randomized trial. Med Decis Making: an Intern J Soc Med Decis Making. 2011;31(1):93–107.

Schroy PC 3rd, Emmons KM, Peters E, et al. Aid-assisted decision making and colorectal cancer screening: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(6):573–83.

Song MK, Ward SE, Happ MB, et al. Randomized controlled trial of SPIRIT: an effective approach to preparing African-American dialysis patients and families for end of life. Res Nurs Health. 2009;32(3):260–73.

Song MK, Donovan HS, Piraino BM, et al. Effects of an intervention to improve communication about end-of-life care among African Americans with chronic kidney disease. Appl Nurs Res. 2010;23(2):65-72.

Taylor KL, Davis JL 3rd, Turner RO, et al. Educating African American men about the prostate cancer screening dilemma: a randomized intervention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(11):2179-88.

Jibaja-Weiss ML, Volk RJ, Granchi TS, et al. Entertainment education for breast cancer surgery decisions: a randomized trial among patients with low health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84(1):41–8.

WestRasmus EK, Pineda-Reyes F, Tamez M, Westfall JM. Promotores de salud and community health workers: an annotated bibliography. Fam Community Health. 2012;35(2):172–82.

Oshima Lee E, Emanuel EJ. Shared decision making to improve care and reduce costs. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(1):6–8.

Peek ME, Cargill A, Huang ES. Diabetes health disparities: a systematic review of health care interventions. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(5 Suppl):101S-156S.

Montori VM, Gafni A, Charles C. A shared treatment decision-making approach between patients with chronic conditions and their clinicians: the case of diabetes. Health Expect. 2006;9(1):25–36.

Peek ME KH, Lopez FY, Xu L, McNulty M, Acree ME, Schneider J. Development of a conceptual framework for understanding shared decision-making among African-American LGB/T patients and their clinicians. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3616-3.

DeMeester RH LF, Moore JE, Cook SC, Chin MH. A model of organizational context and shared decision making: application to LGBT racial and ethnic minority patients. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3608-3.

Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, Dull VT, Frankel RM. Physician-patient communication. The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997;277(7):553–9.

Kasteler J, Kane RL, Olsen DM, Thetford C. Issues underlying prevalence of "doctor-shopping" behavior. J Health Soc Behav Decis. 1976;17(4):329–39.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Funding

This project was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1U18 HS023050) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Finding Answers: Disparities Research for Change Program. Dr. Huang was also supported by the Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research (P30 DK092949) and a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (K24 DK105340).

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Online Appendix 1

(DOCX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nathan, A.G., Marshall, I.M., Cooper, J.M. et al. Use of Decision Aids with Minority Patients: a Systematic Review. J GEN INTERN MED 31, 663–676 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3609-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3609-2