Abstract

Background

Little is known about the factors that influence physicians’ admission decisions, especially among lower acuity patients. For the purpose of our study, non-medical refers to all of the factors—other than the patient’s clinical condition—that could potentially influence admission decisions.

Objective

To describe the influence of non-medical factors on physicians’ decisions to admit non-critically ill patients presenting to the ED.

Design

Cross-sectional study of hospital admissions at a single academic medical center.

Participants

Non-critically ill adult patients admitted to the hospital (n = 297) and the admitting emergency medicine physicians (n = 34).

Main Measures

A patient survey assessed non-medical factors, including primary care access and utilization. A physician survey assessed clinical and non-medical factors influencing the decision to admit. Based on physician responses, admissions were characterized as “strongly acuity-driven,” “moderately acuity-driven,” or “weakly acuity-driven.” Among these admission types, we compared length of stay, cost, and readmission within 30 days to the hospital or ED.

Key Results

Based on the admitting physician’s assessment, we categorized the motivation for admission as strongly acuity-driven in 185 (62 %) admissions, moderately acuity-driven in 92 (31 %), and weakly acuity-driven in 20 (7 %). Per the physician surveys, 51 % of hospitalizations were strongly or moderately influenced by one or more non-medical factors, including lack of information about baseline conditions (23 %); inadequate access to outpatient specialty care (14 %); need for a diagnostic testing or procedure (12 %); a recent ED visit (11 %); and inadequate access to primary care (10 %). Compared with strongly-acuity driven admissions, admissions that were moderately or weakly acuity-driven were shorter and less costly but were associated with similar rates of ED (35 %) and hospital (27 %) readmission.

Conclusions

Non-medical factors are influential in the admission decisions for many patients presenting to the emergency department. Moderately and weakly acuity-driven admissions may represent a feasible target for alternative care pathways.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Hospitalizations comprise the largest component of health care expenditures1 and are increasingly determined by emergency medicine (EM) physicians.2 An understanding of the factors contributing to admission decisions is critical to efforts to reduce hospitalizations.

While clinical condition and acuity primarily influence the likelihood of admission,3 non-medical factors may also contribute.4–13 For the purpose of our study, non-medical refers to all factors, other than a patient’s clinical condition, that potentially influence admission decisions. In retrospective studies, non-medical factors associated with hospital admission include both patient-level (e.g., income,4,5 insurance status,6,7 homelessness,8,9 spouse’s health status,10 health literacy11) and system-level features (e.g., access to care,12,13 provider continuity14). But the role that these non-medical factors play in admission decisions is not well established.

Prior studies have documented variability in hospital admission decisions that is not explained by objective measures of illness severity.15 Even among high acuity patients, a qualitative study of disposition decision-making identified patient behavior, social situation, diagnostic uncertainty, and resource limitations as contributing factors.16 Two previous studies have prospectively surveyed admitting physicians: one from 1976 found that patient-level and health system-level non-medical factors contributed to 21 % of admissions17; a 1994 study in a pediatric population found they contributed to 28 % of admissions.18

We hypothesized that non-medical factors play an important role in admission decisions and are more likely to influence lower acuity admissions. Through physician interviews, we sought to identify the range of non-medical factors implicated in disposition decisions. We then conducted a prospective study to describe a population of non-critically ill adult patients admitted from the emergency department (ED) and to assess the influence of medical and non-medical factors on those admission decisions.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

We conducted a cross-sectional study of hospital admissions in the ED of an urban academic medical center in the northeast USA between February and April 2011. During the study period, care coordinators were employed in the ED primarily to determine Observation or Inpatient status. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Yale University School of Medicine.

Participants

Physicians: All EM attending physicians staffing the ED during the study period participated (n = 34). Patients: Adult patients presenting to the ED were eligible for enrollment at the time an attending physician decided to admit them. Patient exclusion criteria included inability to speak English or Spanish, age <18 years, altered mental status, chief complaint of trauma, and Emergency Severity Index (ESI) of 1. The ESI is a measure of acuity assigned by a triage nurse prior to physician evaluation, with a range of 1 (high) to 5 (low). Patients with an ESI of 1 are often admitted,19,20 but comprise only 2 % of admissions from the ED in our study. We excluded them for logistical reasons (low likelihood that they could complete the patient survey given their trauma or critical illness) and in order to target the patient population for which non-medical factors may influence admission decisions. We enrolled patients during 101 4-h blocks from 7 a.m.–11 p.m., 7 days a week. We used an online random number generator to assign the 4-h blocks and attempted to enroll a consecutive sample of admitted patients within each block. We aimed to enroll 330 patients in order to have 80 % power to detect a 10 % difference between groups, assuming proportions of 0.2–0.3 for the influence of any non-medical factor, based on the prior studies. Two-sided alpha was set at 0.05. All participants, physicians and patients, gave written informed consent.

Study Protocol and Measures

We administered paper-based patient and physician surveys at the time of admission. We also obtained administrative data for each admission, including ESI, primary discharge ICD-9 code, observation status, actual direct cost, payer, length of stay, hospital or ED readmission within 30 days of discharge, and number of hospital or ED admissions in the 12 months preceding enrollment.

Physician Survey

We developed the physician survey using qualitative survey generation methods. We conducted semi-structured interviews with four EM attendings individually to elicit the factors they consider when making hospital admission decisions. No new ideas emerged during the fourth interview. We used these results to develop a preliminary survey, which we piloted individually with five other EM attendings, using a retrospective probing technique.21 We iteratively modified the survey based on the results of each interview. The final version asked the physician to determine the degree of influence that each of 16 factors had on her decision to admit a specific patient. Response options include: strong, moderate, weak, and none. We also asked whether a care coordinator was involved. The physician survey is displayed in Appendix 1.

Patient Survey

In order to characterize the patient population, we created a patient survey comprised of validated and adapted measures. Validated measures included the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2)22 to screen for depression as well as the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine-Short Form (REALM-SF)23,24 and Short Assessment of Health Literacy for Spanish Adults (SAHLSA-50)25 to assess health literacy in English and Spanish, respectively. Individual items were adapted from the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (MOS-SF-36)26 to measure health-related quality of life and from the National Health Interview Survey27 to examine primary care access. We also asked about demographic information; measures of social support, including relationship status and living situation; self-reported health care utilization in the preceding year; and perceived primary care access, including whether the patient has a usual source of care and a primary care provider. Prior to data collection, we piloted the survey for length and clarity with patients in the ED.

Outcome Measures

The main outcomes of interest are the proportions of hospital admission decisions strongly or moderately influenced by acuity or by one or more non-medical factors, as determined by the EM physician.

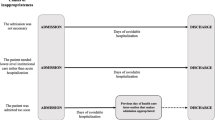

We categorized admissions as “strongly acuity-driven,” “moderately acuity-driven,” or “weakly acuity-driven” based on the first item on the physician survey (influence of “acuity of condition”). We arrived at the threshold for categorization based on the semi-structured interviews and provider survey pilot. Physicians identified Strong, Moderate, Weak, and None as clinically significant response options. A theme common to several interviews was that even when non-medical factors are influential, the influence of clinical acuity is paramount. Hence, “strongly acuity-driven” admissions are based on the physicians’ response of Strong for the influence of “acuity of condition;” “moderately acuity-driven” reflects a response of Moderate; “weakly acuity-driven” corresponds to responses of Weak or None.

We used survey and administrative data to characterize the admissions stratified by acuity, comparing strongly acuity-driven admissions with the moderately and weakly acuity-driven admissions. We chose these groups for comparison given the expectation of a relatively small number of weakly acuity-driven admissions in our sample. During the physician survey development, physicians noted that they would rarely select Weak or None for the influence of acuity given that medical necessity needs to be demonstrated for reimbursement purposes.

Data Analysis

We scanned the survey forms, converted them into a Microsoft Excel file using Cardiff Teleform version 10 software, and used IBM SPSS versions 20 and 21 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) for analysis. We used t tests to compare continuous variables and chi-square tests to compare categorical variables between strongly acuity-driven and moderately/weakly acuity-driven admissions. Non-normally distributed data are described with medians and interquartile ranges and compared with the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test. All tests were two-sided, and alpha was set at 0.05. We used a Kentall’s tau-b test to examine the correlation between the degrees to which acuity and non-medical factors influenced admission.

RESULTS

The ED admitted approximately 1,179 patients during our recruitment blocks. Of these, 443 (38 %) were assessed for eligibility and approached for enrollment. Of the remaining 62 %, we estimate that 2 % were excluded for ESI of 1; an unknown number were excluded for inability to speak English or Spanish or altered mental status; and an unknown number were missed, either because of a shift change (excluded if the attending responsible for the admission decision was not present), high volume leading patients to get transferred to an inpatient bed before being approached for enrollment, or the patient undergoing a procedure or diagnostic test that prevented enrollment.

Of the 443 eligible patients approached during the enrollment blocks, 312 (70.5 %) agreed to participate in the study. We excluded 13 patients because of missing survey data (missing the provider survey, patient survey, or both). An additional two patients had already been enrolled, leaving a final sample size of 297, as displayed in Figure 1. Patient characteristics are shown in the first column of Tables 1 and 2. Missing data are noted in each row. There were no missing data from the physician survey. Physicians responded Yes for involvement of a care coordinator in 11 admissions; for all 11, they responded No to the follow-up question of whether their involvement affected disposition.

Patient enrollment. The ED admitted 4,411 patients from 5 February 2011 to 8 April 2011 (63 days). Based on simple proportions, we estimate that 1,179 patients were admitted during our recruitment blocks [4411 × (101*4)/(63*24) h]. Of these, 443 (38 %) were assessed for eligibility and approached for enrollment. (Note that 1,179 is likely an underestimate and 38 % a corresponding overestimate given that we did not enroll patients between 11 p.m. and 7 a.m., when admission rates are lower.)

Primary Outcome: Influence of Acuity and Non-medical Factors on Hospital Admission Decisions (Physician Survey Data)

Clinical acuity strongly or moderately influenced 93 % of admissions. According to the admitting physician, 185 admissions were strongly motivated by acuity; 92 were moderately influenced; 19 were weakly influenced; and 1 was not influenced at all by acuity (Table 3). Based on the admitting physician’s assessment of the patient’s clinical acuity and need for inpatient care, we categorized 185 admissions (62 %) as “strongly acuity-driven,” 92 (31 %) as “moderately acuity-driven,” and 20 (7 %) as “weakly-acuity driven.” The degrees of influence of acuity and non-medical factors were inversely correlated by a factor of −0.31 (p < 0.001).

Fifty-one percent of the admissions were strongly or moderately influenced by one or more of the non-medical factors identified on the physician survey (Tables 3 and 4). Patient-level non-medical factors that influenced physicians’ decisions to admit are shown in Table 4 and included a recent ED visit (11 %), low likelihood of patient adherence to a discharge plan (9 %), the patient’s living situation and social support (6 %), and problems with transportation if discharged (6 %). Perceived system-level non-medical factors that influenced admission decisions included lack of information about the patient’s baseline condition (23 %), inadequate access to outpatient specialty care (14 %), a patient’s need for a diagnostic testing or procedure that cannot be easily obtained as an outpatient (12 %), inadequate access to primary care (10 %), and a patient’s need for increased nursing care despite existing home or facility-based nursing care (8 %).

Secondary Outcome: Characterization of Admissions Stratified by the Influence of Acuity (Patient Survey, Physician Survey, and Administrative Data)

ESI was higher for the strongly acuity driven admissions (Table 2), although the difference is likely clinically insignificant.18,19 There were no differences between strongly acuity-driven admissions and moderately/weakly acuity-driven admissions in demographic variables, primary care access, provider continuity, or health literacy (Tables 1 and 2). With regard to health care utilization in the year preceding enrollment, frequencies of ambulatory care and inpatient admission did not differ between the strongly acuity-driven and moderately/weakly acuity-driven admissions (Table 2), but patients with moderately or weakly acuity-driven admissions were more likely to use the ED (p = 0.02).

Seventy-one percent of moderately/weakly acuity-driven admissions were strongly or moderately influenced by one or more of the non-medical factors identified on the provider survey (Table 4). Factors that were disproportionately associated with moderately/weakly acuity-driven admissions included, among others, lack of information about the patient’s baseline condition and inadequate access to primary and specialty care.

The strongly acuity-driven and moderately/weakly acuity-driven admissions differed in length of stay and cost (Table 5), with an average difference of 1.9 days and 1798 dollars (Table 5). Observation status and readmission to the ED or hospital within 30 days of discharge did not significantly differ. Nonspecific chest pain was the most common principal diagnosis for all admissions.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the only recent study to prospectively survey physicians about the factors influencing hospital admission of adult patients. Among our sample of non-critically ill patients admitted from the ED, we found that non-medical factors were considered in approximately half of admission decisions and may have been the primary driver in 7 % of the admissions. As health care systems are increasingly incentivized to reduce hospitalizations, mitigating the influence of non-medical factors may be an important target. Health system factors seem to have greater influence than patient non-medical factors on admission decisions, which is encouraging given the feasibility of system-based interventions.

Several non-medical factors identified by physicians reflect the role of diagnostic uncertainty in disposition decisions. These include the lack of information about the baseline condition, need for diagnostic testing, and recent ED visitation. A shared electronic medical record could enable EM physicians to better assess a patient’s baseline condition and improve communication between ambulatory and emergency providers, similar to benefits seen in inpatient and ambulatory settings.28,29 Enhancing EM physicians’ abilities to link discharged patients to timely outpatient primary and specialty care appointments, diagnostic testing, and procedures may increase physicians’ thresholds for admission.

Protocol-based approaches to outpatient management of patients at risk for serious illness may also reduce admissions by decreasing perceived clinical and medico-legal risk of ED discharge. These alternative care pathways require clinical decision tools to assess risk; evidence-based diagnostic and treatment protocols to minimize variability in care; outpatient follow-up that is reliably available on an urgent schedule; efficient communications among patients and providers; support for shared decision-making with patients; and quality-based financial incentives to encourage their development and utilization as an alternative to admission.30 Decision rules currently utilized by EM physicians, such as the TIMI score31 for chest pain and the ABCD2 score32 for TIA, may lead to the admission of clinically stable patients because of a low or intermediate risk of serious illness. It is unclear whether these patients would be captured by the “strongly acuity-driven” or “moderately acuity-driven” admission groups in our study, but many could likely be managed in an alternative environment if evidence-based protocols for urgent outpatient testing were established.30

Other ED-based approaches to facilitate outpatient management of lower-acuity patients require further study but include subspecialty consultation;33 involvement of clinical educators for the management of chronic disease; and care coordination and case management involving nurses and social workers,34 multi-disciplinary outreach,35 and home care.36,37 When compared with strongly acuity-driven admissions, moderately/weakly acuity-driven admissions were associated with similar rates of ED and hospital readmission, suggesting that they may also be an important target for inpatient discharge care coordination. Data regarding the effectiveness of pre- and post-discharge interventions have been mixed, but targeting these lower acuity admissions may be more cost-effective than interventions addressing long-term outpatient disease management.38–45

Primary care access and ED utilization patterns have been examined in multiple studies looking at risk for admission, with varying results.4,6,12,13,46–48 In our study, self-reported ambulatory care did not differ between the patients with strongly acuity-driven and moderately/weakly acuity-driven admissions. However, a physician’s perception that patients lacked access to primary or specialty care played a role in the decisions to admit the lower acuity patients. This may reflect the expectation that even if patients have a primary provider, getting a timely appointment after ED discharge is not guaranteed.49 Our finding that a recent ED visit influenced 16 % of moderately/weakly acuity-driven admissions may indicate physicians’ concerns that ED re-visitation is a predictor of adverse events or may represent outpatient treatment failure. Both might be mitigated by care coordination, which has been shown to be effective in reducing readmissions in patients discharged from the ED.50,51

The strengths of our data include high participation rates (100 % of physicians and 70.5 % of eligible patients); use of validated instruments when available; and iterative development of a physician survey. This study overcomes the limitations of retrospective studies by collecting primary patient data and examining physician decision-making at the time of admission rather than relying on ICD-9 codes and disease severity scores, which give little insight into the acuity of the patient’s illness at the time of admission.52

LIMITATIONS

Our results should be interpreted with caution given that this was a single site study, and admitting practices may vary between hospitals depending on patient population, available resources, and care coordination interventions. The generalizability of our results is further limited by the relatively short study period and the risk of a potentially biased sample, which we cannot assess given the limited information collected on patients outside our sample. In addition, for convenience, we did not include admissions between 11 p.m. and 7 a.m., which may be more or less likely to be influenced by non-medical factors. That said, the purpose of our study was not to identify the exact proportion of admissions influenced by non-medical factors, but rather to characterize a subset of hospitalizations influenced by these factors to see whether they differ in potentially modifiable patient- or system-level features. We do not mean to imply that the proportions and individual factors included in our results are necessarily generalizable to other sites or time periods.

The non-medical factors included on the physician survey were based on limited qualitative data. No new factors emerged during the final interviews used to generate the survey. However, only 71 % of moderately/weakly acuity-driven admissions were influenced by an identified non-medical factor, which suggests that other contributing factors may not have been captured by our survey. We did not describe the variance among physicians’ responses given the relatively large number of physicians and factors. While we attempted to use validated measures for the patient survey, in many cases we only selected individual questions from a validated scale in order to limit the survey time for patients. Finally, there is the potential for type II error when comparing the admissions stratified by acuity.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, our study demonstrates that many factors other than clinical acuity may influence admission decisions. Approximately half of our sample of admissions from the ED were influenced by non-medical factors and as many as 7 % may have been primarily non-medical. These admissions may be a feasible target for alternative care pathways. Further studies are warranted to determine whether targeting modifiable non-medical factors would affect disposition decision-making in the ED.

References

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. National Health Expenditures 2011 Highlights. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/downloads/highlights.pdf. Accessed 4/13/15.

Schuur JD, Venkatesh AK. The growing role of emergency departments in hospital admissions. NEJM. 2012;367:391–3.

Burch VC, Tarr G, Morroni C. Modified early warning score predicts the need for hospital admission and inhospital mortality. Emerg Med J. 2008;25(10):674–8.

Pappas G, Hadden W, Kozak LJ, Fisher GF. Potentially avoidable hospitalizations: inequalities in rates between US socioeconomic groups. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:811–6.

Booth GL, Hux JE. Relationship between avoidable hospitalizations for diabetes mellitus and income level. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:101–6.

Weissman JS, Gatsonis C, Epstein AM. Rates of avoidable hospitalization by insurance status in Massachusetts and Maryland. JAMA. 1992;268:2388–94.

Kruzikas DT, Jiang HJ, Remus D, Barrett ML, Coffey RM, Andrews R. Preventable hospitalizations: a window into primary and preventive care, 2000. JCUP Fact Book No. 5, AHRQ Publication No 040056. 2004. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/data/hcup/factbk5/. Accessed 4/13/15.

Jones B, Gundlapalli AV, Jones JP, Brown SM, Dean NC. Admission decisions and outcomes of community-acquired pneumonia in the homeless population: a review of 172 patients in an urban setting. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:S289–93.

Goss CH, Rubenfeld GD, Park DR, Sherbin VL, Goodman MS, Root RK. Cost and Incidence of social comorbidities in low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia admitted to a public hospital. Chest. 2003;124:2148–55.

Perneger TV, Chopard P, Sarasin FP, Gaspoz JM, Lovis C, Unger PF, Junod AF, Waldvogel FA. Risk factors for a medically inappropriate admission to a department of internal medicine. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1495–500.

DeWalt D, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr K, Pignone MP. Literacy and health outcomes. [Review]. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:1228–39.

Bindman AB, Brumbach K, Osmond D, Komaromy M, Vranizan K, Lurie N, Billings J, Stewart A. Preventable hospitalizations and access to health care. JAMA. 1995;274:305–11.

Parchman ML, Culler SD. Preventable hospitalizations in primary care shortage areas: an analysis of vulnerable Medicare beneficiaries. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:487–91.

Wasson JH, Sauvigne AE, Mogielnicki P, Frey WG, Sox CH, Gaudette C, Rockwell A. Continuity of outpatient medical care in elderly men: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1984;252:2413–7.

Dean NC, Jones JP, Aronsky D, Brown S, Vines CG, Jones BE, Allen T. Hospital admission decision for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: variability among physicians in an emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59:35–41.

Calder LA, Forster AJ, Stiell IG, Carr LK, Perry JJ, Vaillancourt C, Brehaut J. Mapping out the emergency department disposition decision for high-acuity patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:567–76.

Mushlin AI, Appel FA. Extramedical factors in the decision to hospitalize medical patients. AJPH. 1976;66:170–2.

Soulen JL, Duggan AK, DeAngelis CD. Identification of potentially avoidable pediatric hospital use: admitting physician judgment as a complement to utilization review. Pediatrics. 1994;94:421–4.

Baumann MR, Strout TD. Triage of geriatric patients in the emergency department: validity and survival with the emergency severity index. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:234–40.

Tanabe P, Gimbel R, Yarnold PR, Kyriacou DN, Adams JG. Reliability and validity of scores on the emergency severity index version 3. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(1):59–65.

Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2002.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The patient health questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284–94.

Arozullah AM, Yarnold PR, Bennett CL, Soltysik RC, Wolf MS, Ferreira RM, Lee SY, Costello S, Shakir A, Denwood C, Bryant FB, Davis T. Development and validation of a short-form, rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine. Med Care. 2007;45:1026–33.

Health Literacy Measurement Tools: Fact Sheet. January 2009. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/literacy/index.html. Accessed 4/13/15.

Lee SY. Development of an easy-to-use Spanish health literacy test. Health Serv Res. 2006;41:1392–412.

McHorney CA, War JE, Lu R, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994;32:40–66.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2010 National Health Interview Survey Questionnaire. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/quest_data_related_1997_forward.htm. Accessed 4/13/15.

Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–41.

Holroyd-Leduc JM, Lorenzetti D, Straus SE, Sykes L, Quan H. The impact of the electronic medical record on structure, process, and outcomes within primary care: a systematic review of the evidence. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(6):732–7.

Schuur JD, Baugh CW, Hess EP, Hilton JA, Pines JM, Asplin BR. Critical pathways for post-emergency outpatient diagnosis and treatment: tools to improve the value of emergency care. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(6):e52–63.

Pollack CV Jr, Sites FD, Shofer FS, Sease KL, Hollander JE. Application of the TIMI risk score for unstable angina and non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome to an unselected emergency department chest pain population. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:13–8.

Fothergill A, Christianson TJ, Brown RD Jr, Rabinstein AA. Validation and refinement of the ABCD2 score: a population-based analysis. Stroke. 2009;40:2669–73.

Sinoff G, Clarfield AM, Bergman H, Beaudet M. A two-year follow-up of geriatric consults in the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:716–20.

Bristow DP, Herrick CA. Emergency department case management: the dyad team of nurse case manager and social worker improve discharge planning and patient and staff satisfaction while decreasing inappropriate admissions and costs: a literature review. Prof Case Manag. 2002;7(6):243–51.

Caplan GA, Williams AJ, Daly B, Abraham K. A randomized, controlled trial of comprehensive geriatric assessment and multidisciplinary intervention after discharge of elderly from the emergency department—the DEED II study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(9):1417–23.

Brookoff D, Minniti-Hill M. Emergency department-based home care. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:1101–6.

Sinclair D, Ackroyd-Stolarz S. Home care and emergency medicine: a pilot project to discharge patients safely from the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:951–4.

Peikes D, Chen A, Schore J, Brown R. Effects of care coordination on hospitalization, quality of care, and health care expenditures among Medicare beneficiaries: 15 randomized trials. JAMA. 2009;301:603–18.

McCall N, Cromwell J. Results of the medicare health support disease-management pilot program. NEJM. 2011;365:1704–12.

McLean S, Nurmatov U, Liu JL, Pagliari C, Car J, Sheikh A. Telehealthcare for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;7, CD007718.

Shepperd S, Lannin NA, Clemson LM, McCluskey A, Cameron ID, Barras SL. Discharge planning from hospital to home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;1, CD000313.

Phillips CO, Wright SM, Kern DE. Comprehensive discharge planning with post-discharge support for older patients with congestive heart failure: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;291:1358–67.

Courtney M, Edwards H, Chang A, Parker A, Finlayson K, Hamilton K. Fever emergency readmissions and better quality of life for older adults at risk of hospital readmission: a randomized controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of a 24-week exercise and telephone follow-up program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:395–402.

Parker SG, Peet SM, McPherson A, et al. A systematic review of discharge arrangements for older people. Health Technol Assess. 2002;6:i–iv.

Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventison to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520–8.

Oster A, Bindman AB. Emergency department visits for ambulatory care sensitive conditions: insights into preventable hospitalizations. Med Care. 2003;41:198–207.

Billings J, Zeitel L, Lukomnik J, Carey TS, Blank AE, Newman L. Impact of socioeconomic status on hospital use in New York City. Health Aff (Milwood). 1993;12:162–73.

Weinberger M, Oddone EZ, Henderson WG. Does increased access to primary care reduce hospital readmissions? Veterans affairs cooperative study on primary care and hospital readmission. NEJM. 1996;334:1441–7.

Asplin BR, Rhodes KV, Levy H, et al. Insurance status and access to urgent ambulatory care follow-up appointments. JAMA. 2005;294:1248–54.

Guttman A, Afilalo M, Guttman R, Colacone A, Robitaille C, Lang E, Rosenthal S. An emergency department-based nurse discharge coordinator for elder patients: does it make a difference? Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:1318–27.

Caplan GA, Williams AJ, Daly BD, Abraham K. A randomized controlled trial of comprehensive geriatric assessment and multidisciplinary intervention after discharge of elderly from the emergency department—The DEED II Study. Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1417–23.

Ravens MC, Lowe RA, Maselli J, Hsia RY. Comparison of presenting complaint vs discharge diagnosis for identifying “nonemergency” emergency department visits. JAMA. 2013;309:1145–53.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation to Yale University School of Medicine to fund Clinical Research Fellow Ashley E. Lewis Hunter. Preliminary work from this study was presented at the Predoctoral Clinical Research Training Program Meeting on 11 May 2011 in St. Louis, MO.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOC 51 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lewis Hunter, A.E., Spatz, E.S., Bernstein, S.L. et al. Factors Influencing Hospital Admission of Non-critically Ill Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department: a Cross-sectional Study. J GEN INTERN MED 31, 37–44 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3438-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3438-8