ABSTRACT

Purpose

To examine whether patient-reported indicators of medical home performance are associated with health-related quality of life (HRQOL) among adults with type 2 diabetes.

Methods

Cross-sectional survey of 540 patients with Medicaid insurance and type 2 diabetes in Los Angeles County. The Primary Care Assessment Tool was used to measure seven features of medical home performance. The EuroQol EQ-5D-3L (EQ-5D) was used to measure HRQOL.

Results

Higher total medical home performance was correlated with better overall HRQOL. A one-point change in total medical home score was associated with a 0.06-point higher score on the EQ-5D index [95 % confidence interval (CI): 0.01–0.11], which is a clinically meaningful difference. The total score was also significantly associated with a lower likelihood of problems on one domain of the EQ-5D (pain). Longitudinality was the only medical home feature associated with better general health status (ordered odds ratio = 1.78; 95 % CI: 1.04–3.03). The positive relationship of medical home with the EQ-5D appears to be present predominantly among women.

Conclusion

Overall medical home experience is favorably associated with HRQOL among vulnerable adult patients with type 2 diabetes. Provider efforts to improve the overall medical home experience for patients may contribute to improvements in HRQOL.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The patient-centered medical home is a growing focus of medical practice and policy. The medical home is an approach to the delivery of primary care that facilitates partnerships between patients and physicians, and is now widely embraced by major physician organizations.1 While the definitions vary, there are at least four core defining features, which emphasize that care should be accessible, continuous, comprehensive, and coordinated. Three other features sometimes included are family-centeredness, community orientation, and cultural competence. A medical home is anticipated to improve patient care and thus the health of patients over time.

A medical home may be particularly important for people with chronic disease. People with type 2 diabetes—a disease that is now the seventh leading cause of death nationally2—receive the majority of their diabetes care in a primary care setting.3 Their demands on primary care (and the health care system as a whole) are large, requiring not only regular testing and active medication management, but also ongoing health education to encourage lifestyle changes and effective coordination with specialists. How primary care physicians provide these facets of care thus has great potential to directly affect patient outcomes.

Pilot medical home studies have observed mixed results in processes of care, clinical measures of diabetes care (including blood glucose control), and hospitalization and emergency department utilization.4 Two recent studies add to this complexity by suggesting that medical home performance, as defined by the National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA) and assessed from the provider perspective, had no impact on most diabetes quality measures, with the single exception of improved nephropathy screening.5 , 6

But clinical measures are only part of the story for adults with diabetes. The disease itself, as well as fears associated with complications in uncontrolled diabetes, may directly affect patient functioning and well-being.7 Given that primary care is designed to be whole-person-focused and to support patients over time, medical home performance may have a particular impact on the daily quality of life and functioning among adults with diabetes.

Measures of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) are increasingly reported in health services research because they examine functioning in multiple aspects of life. They offer a unique patient-reported picture of health that complements disease parameters or physician assessments of disease states.8 , 9 HRQOL measures are able to effectively distinguish between disease states and respond to changes in clinical care, and are sensitive outcome measures. The HRQOL instrument in this study—the EuroQoL—has been used to study health care interventions10 and in diabetes research.11

This study adds to the body of work on the primary care medical home by examining whether patient-reported indicators of medical home experience are associated with HRQOL and general health status among adults with type 2 diabetes. We focus on vulnerable adults covered by Medicaid insurance, for whom diabetes is more prevalent and who experience more barriers to effectively managing their disease.12–14 The results have particular implications for Hispanic/Latino patients, as they comprise the majority of the Medicaid population in Los Angeles, and the majority of our sample.

METHODS

Study Sample

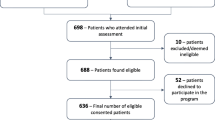

Data for this study are from a cross-sectional survey of patients in Los Angeles County aged 18–64 years with type 2 diabetes and Medicaid health insurance. Sampling was conducted in two stages. First, primary care physicians (i.e., family medicine, internal medicine, and general practice) were identified through publicly available network data for one of the largest Medicaid plans in the county. From a list of 471 eligible physicians, they were randomly drawn and recruited until we reached our target sample size of 100 (n = 104, 75 % response rate).

Second, all physicians were asked to refer a minimum of 10 patients with type 2 diabetes meeting the study criteria, using one of two methods: retrospective or prospective referrals. The retrospective referral method involved referring all eligible patients who had visited the office, working from most recent up to the past six months. Before referral, the office staff called the patients and, used a study-provided script offer them the chance to opt out of the referral. The prospective method was similar. Physicians referred all eligible patients scheduled to visit the office for up to the next six months, or until a minimum of 10 referrals were made. In this case, a flier was provided to each patient about the study by the office staff, giving the patient a chance to opt out of the referral.

This study was approved and given an IRB waiver of HIPAA authorization by the USC Office for the Protection of Research Subjects. The potential for physicians to hand-select patients was reduced by the requirement that “all” patients meeting the criteria were to be referred. A total of 1.8 % of patients opted out of being the referral. We then randomly selected patients until we reached a goal of about five patients per physician. There were no differences in opt-out rates, response rates, or demographics between methods.

Measures

Medical Home Performance

We used the Johns Hopkins’ Primary Care Assessment Tool–Adult Expanded version (PCAT) to assess patient-reported indicators of medical home quality. While definitions vary across organizations, there is consensus on at least four core features--accessibility, longitudinality (or continuity), comprehensiveness, and coordination15–18--all of which are measured by the PCAT. The PCAT consists of 96 questions that evaluate the four core features above and three others that are often included in definitions of a medical home: 1) community-oriented care, 2) family-centered care, and 3) cultural competence.

First-contact care refers to the concept that care is available and first sought from the medical home when a new health or medical need arises. Longitudinality refers to the use of a regular source of care over time and the relationship that develops. Comprehensiveness is the range of services available to and received by the patient. Coordination refers to the linking of health services so that patients receive appropriate care for all of their health problems. Community-oriented care refers to the concept that providers strive to be aware of, and oriented to, the health needs of a community. Family-centered care is the recognition of the family as a participant in the diagnosis, treatment, and recovery of patients. Cultural competence refers to care that respects the language, beliefs, and attitudes of people.

Each question is scored using a Likert-type response scale as follows: “definitely not” (1 point), “probably not” (2 points), “probably” (3 points), and “definitely” (4 points). The PCAT is scored such that each feature is calculated as the average of the responses to the questions comprising the feature. A total medical home score is the average of the seven feature scores such that each feature is equally weighted. Previous work has shown that the overall PCAT has good reliability and validity.19 , 20 The PCAT has good construct validity, with the seven features accounting for 88 % of the total 96-item variance. Internal consistency reliability for the features has ranged from 64 % to 96 %. The PCAT has been successfully used to detect differences in primary care across providers and delivery systems.21–23

EuroQol (EQ-5D)

The EQ-5D is a preference-based global, rather than disease-specific, measure of HRQOL.10 It consists of five questions about mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain, and anxiety. Each dimension has three levels describing the patient's health state on that day—no problems, moderate problems, or severe problems—leading to 243 unique health states. The health states are expressed in an index using a preference-based set of weights for the U.S. population.24 This index is an expression of these states, taking into account the desirability or undesirability of each state. After weighting, the index is anchored by scores 1.0 (full health) and 0.0 (dead), with some states being worse than death (<0). The EQ-5D index scores in this study ranged from −0.04 (severe problems) to 1.0 (no problems). For two patients in our analysis with EQ-5D index scores below zero, both reported being “confined to bed” (mobility) and experiencing “extreme pain or discomfort” (pain). We also presented the EQ-5D dimensions using the three ordinal response levels.

General Health

Status: Self-reported general health status is the response to the question, “In general, would you say your health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” We re-coded the responses into three ordinal categories: 1) fair/poor, 2) good, and 3) excellent/very good.

Covariates

Age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, employment, marital status, the length of time with diabetes (i.e., duration), and patient-reported insulin use were accounted for in the analysis. Ethnicity was categorized into Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic. Education included less than high school vs. high school graduate or equivalent (GED) or higher. Marital status was coded as married vs. not-married. Employment status was coded as employed vs. unemployed. Duration of diabetes was included because of its negative association with HRQOL that likely indicates disease progression or severity.11 Patient-reported insulin use was included because some studies have observed that insulin use is associated with HRQOL25–27 and because it may further help account for disease severity.

Analysis

All analyses were completed with the patient as the unit of analysis. Each patient had his/her own medical home score, even if they shared a physician. This approach reflects the concept that the medical home experience can validly vary even among patients of the same physician or clinic. Because patients were nested within physicians, we estimated our sample size to account for clustering, and examined the necessity of accounting for clustering in our analysis using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of the total medical home score. The ICC describes the extent to which responses are correlated among patients seeing the same physicians. In this case, the ICC was 0.20, which is a moderate correlation, suggesting that patients of the same physician reported primary care similarly (although not identically), so we adjusted for clustering using survey procedures in Stata13.

Descriptive statistics were obtained for the independent measures and the dependent measures. Next, we examined differences in medical home scores and demographics among categories of the EQ-5D score, dichotomized at the 50th percentile, and the ordinal three-level EQ-5D domains and general health status. To test significance, t tests were used to compare medical home mean scores across the dichotomized EQ-5D index, and post hoc means tests (and F-statistics) were used to compare the mean medical home scores across the ordinal EQ-5D domains and general health status. Chi-squared tests were used to test the relationship between all health measures and the demographics.

Next, two multivariable linear regressions of medical home on the EQ-5D index were performed—one for the total medical home score and then one for the seven medical home features entered simultaneously—both while controlling for study covariates. A set of ordered logistic regressions were performed for the ordinal EQ-5D dimensions and general health status. The ordered odds ratio (OR) is interpreted as the average likelihood of moving between the levels of an ordinal dependent measure. An ordered OR greater than 1.0 would reflect the average odds of moving up one response category of the three (e.g., from no problem to moderate, or from moderate to severe).

Finally, because the sample was heavily female and Hispanic, and because these groups may use health care differently than their counterparts, we examined the potential for the relationship between the total medical home score and HRQOL to vary according to these factors. Where interaction terms were significant (gender), separate regressions for men and women were run. Figure 1 shows the plot of the interaction effect using a graph of fitted values (i.e., the slope of the relationship between the medical home score and EQ-5D index, adjusted for our covariates).

RESULTS

Data collection was completed between June 2012 and May 2013. A total of 540 patient interviews were completed by telephone in Spanish (55.3 %), English (43.7 %), and Mandarin or Armenian (1 %). The most conservative response rate (56.9 %) was calculated as the total completed patient interviews (n = 540) of all patients sampled (n = 949). About one-fifth of all patients sampled had an incorrect phone number and address (n = 165) and were not considered usable. The response rate among just the usable listings (i = 784) was 68.9 %. Among patients that we reached and spoke with (i = 635), the response rate was 85.0 %.

Table 1 presents distributions of individual characteristics of the 540 patients surveyed. Most of the patients were female (69.26 %), Hispanic (77.41 %), with lower than high school education (56.48 %), and unemployed (72.04 %). The average total medical home score was 3.12 out of 4 points; the most highly scored feature was longitudinality (3.44), and the most poorly scored was the degree of community orientation (2.10). With regard to HRQOL, the average index score was 0.67, identical to the expected EQ-5D value among a general sample of adult patients with type 2 diabetes.11 Few patients in our sample had problems with self-care activities, while most patients had problems with pain.

Table 2 presents the bivariate relationships between the medical home features and our measures of HRQOL. The total medical home score was significantly associated with two of the EQ-5D dimensions (pain and anxiety), though most estimates were in the direction of a positive correlation. The features of medical home longitudinality and community orientation were each associated with two dependent variables , but otherwise there was no consistent pattern. Among the covariates, older age, non-Hispanic ethnicity, unemployed status, not being married, and using insulin were associated with poorer health.

Table 3 presents the multivariable linear regression relationship between the medical home features and HRQOL, adjusting for the study covariates. The total medical home score was significantly associated with the EQ-5D index and one of the dichotomous dimensions. After adjustment, a one-point change in total medical home score was associated with a 0.06-point higher score in the EQ-5D index (95 % CI: 0.01–0.11). Most of the features of a medical home were not consistently associated with the dependent variables. Longitudinality was associated with a lower likelihood of problems with anxiety and better general health status.

Additional regressions were completed testing the interactions of the total medical home score with gender or Hispanic ethnicity. No interaction terms were statistically significant with Hispanic ethnicity; however, interactions with gender were significant for three dependent measures. The relationship of the medical home total score with the EQ-5D index was significant for women but not for men (gender interaction term B = 0.14, CI: 0.03-0.25, i < .01), so separate regression slopes for women and men are shown in Figure 1, and for the EQ-5D domains of activity and pain (not shown).

DISCUSSION

Higher total medical home experience was correlated with a better overall HRQOL. In other work benchmarking EQ-5D scores for patients with type 2 diabetes, a difference of just 0.03 points on the index separated patients with any vascular complications from those with none. The effect size of 0.06 points for total medical home score on HRQOL is more than half of the 0.10-point difference observed between patients with no complications and those with retinopathy, and is about one-third of the 0.18-point difference associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain.11 Thus, changes in the delivery of primary care may have clinically meaningful benefits to the quality of life of patients with diabetes.

The total medical home score was only sometimes a factor in our sub-analyses of the five EQ-5D dimensions and general health status. It was significantly linked with a lower likelihood of problems with pain and was borderline significant for anxiety (p = 0.06). The absence of an effect for each HRQOL measure may suggest that the medical home impacts some features of HRQOL more than others . Alternately, this may also reflect the value of primary care and its whole-person focus, with the collective EQ-5D index capturing the combined effects of smaller changes in the five dimensions. This whole-person focus of primary care might also explain why no individual medical home feature was significantly associated with more than two dimensions of HRQOL. Our study differs from those showing a particular relationship between first-contact care and HRQOL among children 28, 29, and between access and lower costs for adults.30

The observation that the medical home experience appears more strongly correlated with the EQ-5D for women is a novel finding . It is possible that women benefit more from high-performing primary care because they tend to use services more frequently, particularly preventive care.31 , 32 Women’s interactions with providers also tend to differ from those of men, with women’s primary care visits tending to address more questions, involve more screenings, and more frequently include emotional counseling.33 , 34 Since several medical home features involve the patient-provider relationship, it is possible that women benefit more directly from the delivery of these services. Gender differences in medical home experience deserve further investigation, given mixed results in our analyses.

There are some limitations to this study. First, our ability to draw causal inferences was limited due to the cross-sectional nature of this analysis. Second, selection bias is possible, as providers and patients who participated might have greater expertise in diabetes (in the case of physicians) or more extreme diabetes issues in either direction for patients. We aimed to reduce selection bias through random sampling, incentivizing participation to obtain a high response rate, and monitoring patient diabetes measures for extreme cases. Third, the data we collected are predominantly from female Hispanic patients, so the results may not be fully generalizable nationally. Fourth, features used to assess medical home align closely, but not perfectly, with the other measures of medical home (such as those by NCQA), and so may not reflect a complete measure of medical home quality. The NCQA measures are different in that they are reported by physicians and include elements of reimbursement not in the PCAT.

In conclusion, this study suggests that the medical home experience of vulnerable patients with type 2 diabetes may contribute to HRQOL. The continued national policy and practice emphasis on the medical home model requires empirical data to inform recommendations about the widespread adoption of this model. This study provides some new evidence of the potential value of this model, above and beyond clinical measures, for the daily quality-of-life experiences of adults with diabetes.

Abbreviations

- PCAT:

-

Primary care assessment tool

- HRQOL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- EQ-5D:

-

EuroQuol-5D-3 L

REFERENCES

Kellerman R, Kirk L. Principles of the patient-centered medical home. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:774–775.

Hoyert D, Xu J: Deaths Preliminary data for 2011. In National vital statistics reports. Hyattsville, MD, National Center for Health Statistics, 2012

Sharma MA, Cheng N, Moore M, Coffman M, Bazemore AW. Patients with high-cost chronic conditions rely heavily on primary care physicians. J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27:11–12.

Bojadzievski T, Gabbay RA. Patient-centered medical home and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1047–1053.

Friedberg MW, Schneider EC, Rosenthal MB, Volpp KG, Werner RM. Association between participation in a multipayer medical home intervention and changes in quality, utilization, and costs of care. JAMA. 2014;311:815–825.

Rosenthal MB, Friedberg MW, Singer SJ, Eastman D, Li Z, Schneider EC. Effect of a multipayer patient-centered medical home on health care utilization and quality: the Rhode Island chronic care sustainability initiative pilot program. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1907–1913.

Currie CJ, Morgan CL, Poole CD, Sharplin P, Lammert M, McEwan P. Multivariate models of health-related utility and the fear of hypoglycaemia in people with diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:1523–1534.

Khanna D, Tsevat J. Health-related quality of life–an introduction. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13(Suppl 9):S218–223.

Ahmed S, Berzon RA, Revicki DA, Lenderking WR, Moinpour CM, Basch E, Reeve BB, Wu AW. Research ISfQoL: The use of patient-reported outcomes (PRO) within comparative effectiveness research: implications for clinical practice and health care policy. Med Care. 2012;50:1060–1070.

Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. 2001;33:337–343.

Janssen MF, Lubetkin EI, Sekhobo JP, Pickard AS. The use of the EQ-5D preference-based health status measure in adults with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2011;28:395–413.

Hu R, Shi L, Rane S, Zhu J, Chen CC Insurance, Racial/Ethnic, SES-Related Disparities in Quality of Care Among US Adults with Diabetes. J Immigr Minor Health 2013

Heisler M, Smith DM, Hayward RA, Krein SL, Kerr EA. Racial disparities in diabetes care processes, outcomes, and treatment intensity. Med Care. 2003;41:1221–1232.

Richard P, Alexandre PK, Lara A, Akamigbo AB. Racial and ethnic disparities in the quality of diabetes care in a nationally representative sample. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8:A142.

Starfield B. Primary Care: Balancing Health Needs, Services, and Technology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998.

Donaldson M, Yordy K, Lohr K, Vanselow N. Primary Care: America's Health in a New Era. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996.

Rosenthal TC. The medical home: growing evidence to support a new approach to primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21:427–440.

Sia C, Tonniges TF, Osterhus E, Taba S. History of the medical home concept. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1473–1478.

Shi L, Starfield B, Xu J. Validating the Adult Primary Care Assessment Tool. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:E1.

Cassady C, Starfield B, Hurtado M, Berk R, Nanda J, Friedenberg L. Measuring consumer experiences with primary care. Pediatrics. 2000;105:998–1003.

Starfield B, Cassady C, Nanda J, Forrest CB, Berk R. Consumer experiences and provider perceptions of the quality of primary care: implications for managed care. J Fam Pract. 1998;46:216–226.

Shi L, Starfield B, Xu J, Politzer R, Regan J. Primary care quality: community health center and health maintenance organization. South Med J. 2003;96:787–795.

Haggerty JL, Pineault R, Beaulieu MD, Brunelle Y, Gauthier J, Goulet F, Rodrigue J. Practice features associated with patient-reported accessibility, continuity, and coordination of primary health care. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:116–123.

Oemar M, Oppe M. EQ-5D-3L User Guide: Basic Information on How to Use the EQ-5D-3L Instrument Version 5.0. The Netherlands: EuroQol Group; 2013.

Bradley C, Gilbride CJ. Improving treatment satisfaction and other patient-reported outcomes in people with type 2 diabetes: the role of once-daily insulin glargine. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2008;10(Suppl 2):50–65.

Lee LJ, Fahrbach JL, Nelson LM, McLeod LD, Martin SA, Sun P, Weinstock RS. Effects of insulin initiation on patient-reported outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes: results from the durable trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;89:157–166.

Ashwell SG, Bradley C, Stephens JW, Witthaus E, Home PD. Treatment satisfaction and quality of life with insulin glargine plus insulin lispro compared with NPH insulin plus unmodified human insulin in individuals with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1112–1117.

Stevens GD, Vane C, Cousineau MR. Association of experiences of medical home quality with health-related quality of life and school engagement among Latino children in low-income families. Health Serv Res. 2011;46:1822–1842.

Stevens GD, Pickering TA, Laqui SA. Relationship of medical home quality with school engagement and after-school participation among children with asthma. J Asthma. 2010;47:1001–1010.

Fields D, Leshen E, Patel K. Analysis & commentary. Driving quality gains and cost savings through adoption of medical homes. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:819–826.

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient gender differences in the prediction of medical expenditures. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19:1925–1932.

Bertakis KD, Azari R, Helms LJ, Callahan EJ, Robbins JA. Gender differences in the utilization of health care services. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:147–152.

Bertakis KD. The influence of gender on the doctor-patient interaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76:356–360.

Tabenkin H, Goodwin MA, Zyzanski SJ, Stange KC, Medalie JH. Gender differences in time spent during direct observation of doctor-patient encounters. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2004;13:341–349.

Acknowledgments

Funders: This project was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases, Grant #R01DK090397. The study was approved by the USC Office for the Protection of Research Subjects. Thank you to the many community health centers, physicians and patients who participated in this study. A list of the physicians and health centers who agreed to be acknowledged for their participation can be obtained from the corresponding author. Thank you to the two anonymous reviewers who provided helpful analytic ideas that shaped the content and results of this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The study was approved by the USC Office for the Protection of Research Subjects. The authors have no financial or other conflicts of interest regarding the results that are presented in this study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stevens, G.D., Shi, L., Vane, C. et al. Primary Care Medical Home Experience and Health-Related Quality of Life Among Adult Medicaid Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. J GEN INTERN MED 30, 161–168 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-3033-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-3033-4