Abstract

Background

The quality of the relationship between a patient and their usual source of care may impact outcomes, especially after an acute clinical event requiring regular follow-up.

Objective

To examine the association between the presence and strength of a usual source of care with mortality and readmission after hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction (AMI).

Design

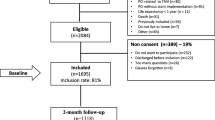

Prospective Registry Evaluating Myocardial Infarction: Event and Recovery (PREMIER), an observational, 19-center study.

Patients

AMI patients discharged between January 2003 and June 2004.

Main Measures

The strength of the usual source of care was categorized as none, weak, or strong based upon the duration and familiarity of the relationship. Main outcome measures were readmissions and mortality at 6 months and 12 months post-AMI, examined in multivariable analysis adjusting for socio-demographic characteristics, access and barriers to care, financial status, baseline risk factors, and AMI severity.

Key Results

Among 2,454 AMI patients, 441 (18.0 %) reported no usual source of care, whereas 247 (10.0 %) and 1,766 (72.0 %) reported weak and strong usual sources of care, respectively. When compared with a strong usual source of care, adults with no usual source of care had higher 6-month mortality rates [adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) = 3.15, 95 % CI, 1.79–5.52; p < 0.001] and 12-month mortality rates (aHR = 1.92, 95 % CI, 1.19–3.12; p = 0.01); adults with a weak usual source of care trended toward higher mortality at 6 months (aHR = 1.95, 95 % CI, 0.98–3.88; p = 0.06), but not 12 months (p = 0.23). We found no association between the usual source of care and readmissions.

Conclusions

Adults with no or weak usual sources of care have an increased risk for mortality following AMI, but not for readmission.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

Pancholi M. Reasons for Lacking a Usual Source of Care: 2001 Estimates for the US Civilian Noninstitutionalized Population. www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st32/stat32.pdf. Accessed January 22, 2014.

NCHS. Early release of selected estimates based on data from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010.

Xu KT. Usual source of care in preventive service use: a regular doctor versus a regular site. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(6):1509–1529.

Saultz JW, Lochner J. Interpersonal continuity of care and care outcomes: a critical review. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(2):159–166.

DeVoe JE, Fryer GE, Phillips R, Green L. Receipt of preventive care among adults: insurance status and usual source of care. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(5):786–791.

Blewett LA, Johnson PJ, Lee B, Scal PB. When a usual source of care and usual provider matter: adult prevention and screening services. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1354–1360.

Rosenblatt RA, Wright GE, Baldwin LM, et al. The effect of the doctor-patient relationship on emergency department use among the elderly. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(1):97–102.

Petterson SM, Rabin D, Phillips RL Jr, Bazemore AW, Dodoo MS. Having a usual source of care reduces ED visits. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(2):94.

Ettner SL. The relationship between continuity of care and the health behaviors of patients: does having a usual physician make a difference? Med Care. 1999;37(6):547–555.

Goldstein RB, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Johnson MO, et al. Insurance coverage, usual source of care, and receipt of clinically indicated care for comorbid conditions among adults living with human immunodeficiency virus. Med Care. 2005;43(4):401–410.

DeVoe JE, Tillotson CJ, Wallace LS. Usual source of care as a health insurance substitute for US adults with diabetes? Diabetes Care. 2009;32(6):983–989.

Spatz ES, Ross JS, Desai MM, Canavan ME, Krumholz HM. Beyond insurance coverage: usual source of care in the treatment of hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. Data from the 2003–2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am Heart J. 2010;160(1):115–121.

Starfield B. Primary Care: Balancing Health Needs, Services, and Technology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998.

Ratanawongsa N, Karter AJ, Parker MM, et al. Communication and medication refill adherence: the Diabetes Study of Northern California. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(3):210–218.

Beck RS, Daughtridge R, Sloane PD. Physician-patient communication in the primary care office: a systematic review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15(1):25–38.

Spertus JA, Peterson E, Rumsfeld JS, Jones PG, Decker C, Krumholz H. The Prospective Registry Evaluating Myocardial Infarction: Events and Recovery (PREMIER)—Evaluating the impact of myocardial infarction on patient outcomes. Am Heart J. 2006;151(3):589–597.

Newman TB, Brown AN. Use of commercial record linkage software and vital statistics to identify patient deaths. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997;4(3):233–237.

Eagle KA, Lim MJ, Dabbous OH, et al. A validated prediction model for all forms of acute coronary syndrome: estimating the risk of 6-month postdischarge death in an international registry. JAMA. 2004;291(22):2727–2733.

Babyak MA. What you see may not be what you get: a brief, nontechnical introduction to overfitting in regression-type models. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(3):411–421.

Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, Holford TR, Feinstein AR. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(12):1373–1379.

Kangovi S, Grande D. Hospital readmissions–not just a measure of quality. JAMA. 2011;306(16):1796–1797.

Bindman AB, Grumbach K, Osmond D, et al. Preventable hospitalizations and access to health care. JAMA. 1995;274(4):305–311.

Weinberger M, Oddone EZ, Henderson WG. Does increased access to primary care reduce hospital readmissions? Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Primary Care and Hospital Readmission. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(22):1441–1447.

Oddone EZ, Weinberger M, Giobbie-Hurder A, Landsman P, Henderson W. Enhanced access to primary care for patients with congestive heart failure. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Primary Care and Hospital Readmission. Eff Clin Pract. 1999;2(5):201–209.

Acknowledgments

Contributors

None.

Funders

We gratefully acknowledge support from the grant U01-HL105270-03 (Center for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at Yale University) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Krumholz was supported by grant U01 HL105270-03 (Center for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at Yale University) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Ross is supported by the National Institute on Aging (K08 AG032886) and by the American Federation for Aging Research through the Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award Program. CV Therapeutics and CV Outcomes, a 501(c)(3) corporation funded the PREMIER registry.

Prior Presentations

American Heart Association: Quality of Care and Outcomes Research, Poster Presentation, 2011.

Conflict of Interests

Drs. Krumholz and Ross work under contract with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to develop and maintain performance measures and are the recipients of a research grant from Medtronic, Inc., through Yale University. Dr. Krumholz is chair of a cardiac scientific advisory board for UnitedHealth, and Dr. Ross is a member of a scientific advisory board for FAIR Health. Dr. Spertus reports funding from NIH, AHA, ACCF, Gilead, Genentech, Amorcyte, Eli Lilly and Abbott Vascular. He serves as a consultant to United Healthcare, Genentech, Gilead, Novartis, Janssen, and Amgen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(PDF 207 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Spatz, E.S., Sheth, S.D., Gosch, K.L. et al. Usual Source of Care and Outcomes Following Acute Myocardial Infarction. J GEN INTERN MED 29, 862–869 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2794-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2794-0