Abstract

Background and Aims

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a spectrum of disease that includes nonerosive reflux disease (NERD), erosive reflux disease (ERD), and Barrett’s esophagus (BE). Treatment outcomes for patients with different stages have differed in many studies. In particular, acid suppressant medication therapy is reported to be less effective for treating patients with NERD and Barrett’s esophagus. The aims of this study were to investigate (1) the role of mechanical factors including hiatal hernia and lower esophageal sphincter (LES) competence in the spectrum of GERD and (2) outcomes of Nissen fundoplication.

Methods

From the records of patients who had undergone laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication after an abnormal pH study, we identified 50 symptomatic consecutive patients with each of the GERD stages: (1) NERD, (2) mild ERD, defined as esophagitis that was healed with acid suppression therapy, (3) severe ERD, defined as esophagitis that persisted despite medical therapy, and (4) BE. Exclusion criteria were normal distal esophageal acid exposure, esophageal pH monitoring performed elsewhere, antireflux surgery less than 1 year previously or previous fundoplication, and a named esophageal motility disorder or distal esophageal low amplitude hypomotility. Patients who could not be contacted for the study were also excluded. All patients completed a detailed preoperative questionnaire; underwent preoperative upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, stationary manometry, and distal esophageal pH monitoring; and were interviewed at least 1 year after operation.

Results

One hundred sixty patients meeting the entry criteria were studied. The mean follow-up period was 36.7 months. The only significant preoperative symptom difference was that patients with BE had more moderately severe or severe dysphagia compared to patients with NERD. Patients with severe ERD or BE had a significantly higher prevalence of hiatal hernia, lower LES pressures, and more esophageal acid exposure. Hiatal hernia and hypotensive LES were present in most patients with severe ERD or BE but in only a minority of patients with NERD or mild ERD. Surgical therapy resulted in similarly excellent symptom outcomes for patients in all GERD categories.

Conclusions

Compared to mild ERD and NERD, severe ERD and BE are associated with significantly greater loss of the mechanical antireflux barrier as reflected in the presence of hiatal hernia and LES measurements. Restoration of the antireflux barrier and hernia reduction by laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication provides similarly excellent symptom control in all patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a spectrum of disease that extends from nonerosive reflux disease (NERD), in which there are no mucosal breaks on endoscopy, to erosive esophagitis or to Barrett’s esophagus (BE).1 It is currently estimated that between 50% and 70% of patients with GERD have NERD,2–4 5% to 10% have BE, and the remainder have erosive reflux disease (ERD), with either esophageal erosions or ulcerations.5 As a group, patients with NERD have symptom and quality of life scores similar to patients with erosive reflux disease (ERD).4,6 Patients can progress from NERD to ERD, even on proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, but progression from ERD to BE is uncommon and from NERD to BE is very uncommon.7–9 Labenz et al. reported on the progression of GERD (ProGERD) study of 3,894 patients with GERD who underwent baseline endoscopy and repeat endoscopy at 2 years.8 As is characteristic of a disease spectrum, many patients had progressed or regressed from one GERD stage to another. Approximately one quarter of patients with NERD had progressed to mild ERD and most patients with ERD had regressed to NERD (treatment was allowed). Patients with severe ERD had the highest rate (5.8%) of progression to BE.8

Numerous studies have shown that patients with ERD or BE are effectively treated by antireflux surgery, with safe, long-term control of reflux symptoms, normalization of esophageal acid and nonacid exposure, and a significant improvement in quality of life.10–14 Few data, in contrast, are available on the results of surgical therapy for all stages of the GERD spectrum including NERD.13,15 The results of surgical treatment are especially important for patients with NERD as medical treatments are widely reported as being less effective for these patients.16–18 In this study, we investigated the influence of the endoscopically defined GERD stage on the outcome of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. We also compared the demographic, clinical, and physiologic features of patients with different stages of GERD. In particular, we studied the importance of hiatal hernia and lower esophageal sphincter competence, factors which have received less emphasis in other studies.

Patients and Methods

The clinical and esophageal physiology records of patients who had been treated by laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine Department of Foregut Surgery (USC) were reviewed. All patients had symptoms suggestive of reflux disease. The mucosal appearance at preoperative endoscopies was used to identify 50 consecutive patients with NERD, 50 consecutive patients with mild ERD, 50 consecutive patients with severe ERD, and 50 consecutive patients with BE. The sample size of 50 patients was selected after a preliminary review of our database indicated that this was likely the maximum number of patients with NERD and persistent esophagitis (severe ERD) available for inclusion in the study period. Since the statistical power of a study is increased by only a relatively small and inefficient amount when the sample sizes are unequal, we did not include all available patients but aimed to limit the sample size to 50 patients in each group.

Patients were classified as having NERD if they had no record of esophagitis, with esophagitis defined by the presence of erosions or ulcerations (modified Savary Miller classification19) at any endoscopy. Patients who had received acid suppressant medication therapy prior to their initial endoscopy were excluded from this group. The acid suppressant medication history prior to endoscopy at USC was obtained from the referral letters, USC surgeon’s files and reports, and from the patients.

Patients with no erosive esophagitis at preoperative endoscopy but a history of ERD at a previous endoscopy that had been healed by acid suppressant drug therapy were classified as having mild (or healed) ERD. Severe ERD was defined as persistent or nonhealed esophagitis and was diagnosed when esophagitis was found at the preoperative endoscopy in patients who had received at least some acid suppressant therapy. This included PPI therapy in all cases but we did not include the type or dose of medication received as a factor or perform a subanalysis of the medical therapy as many larger studies have addressed the effectiveness of acid suppressive medication using more robust methods including many randomized controlled trials. All patients with ERD thus had at least two endoscopies. BE was diagnosed by the presence of microscopic intestinal metaplasia in a macroscopic columnar-lined esophagus of any length.

All patients underwent preoperative endoscopy performed by the authors at this institution. The results of endoscopies performed elsewhere were obtained from the medical history and the documents and letters of the referring physician. In order to ensure that only patients with definite GERD were studied, only patients with abnormal distal esophageal acid exposure were included.

Patients were excluded if they had undergone Nissen fundoplication less than 1 year previously, if they had had more than one previous antireflux operation, or if they could not be contacted for this study. Patients who had not had a preoperative ambulatory pH study at this institution were also excluded, as were those with a named esophageal motility disorder or distal esophageal low amplitude hypomotility, defined as a mean contraction amplitude less than 20 mmHg. A hiatal hernia was diagnosed when the gastroesophageal junction was located 2 cm or more proximal to the crural impression at endoscopy, with the gastroesophageal junction defined as the proximal extent of the gastric rugal folds.

Symptom Assessment

All patients completed a structured symptom questionnaire at the time of their esophageal pH examination. The symptom of heartburn was graded as 0 (none), 1 (mild; occasional episodes), 2 (moderate; primary reason for medical visit), or 3 (severe; effects daily life). Regurgitation was graded as 0 (none), 1 (mild; occasional episode after straining or large meal), 2 (moderate, predictable with position change or straining), or 3 (severe, effects daily life, possibly with a history of aspiration). Dysphagia was graded as 0 (none), 1 (mild; occasionally with coarse foods; lasting a few seconds), 2 (moderate; requiring clearing with liquids), or 3 (severe; requiring a semiliquid diet and with a history of meat impaction). These descriptors were also used for postoperative symptom assessment. In order to limit the number of statistical comparisons and the consequent risk of false positive findings, the symptom findings were classified as either “none or mild” or “moderate or severe”.

Manometry

All patients underwent preoperative manometry testing. Stationary motility was performed after an overnight fast using a single catheter assembly consisting of five polyethylene tubes bonded together with five lateral openings placed at 5-cm intervals from the distal end and oriented radially around the circumference. Using a pneumohydraulic low compliance pump (Arndorfer Medical Specialties, Greendale, WI, USA), the catheter was perfused with distilled water at a constant rate of 0.6 mL/min. A stationary pull through of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and a manual analysis of the polygraph recordings were performed. LES resting pressure was measured at the respiratory inversion point, as described previously.20 The resting pressure, overall length, and abdominal length of the LES were calculated from the mean of the five recordings. A structurally defective LES was defined either by a resting pressure <6 mmHg, overall length <2 cm, abdominal length <1 cm, or any combination of these. Assessment of the esophageal body motility was performed as described previously.20

pH and Bilirubin Monitoring

All the patients underwent 24-h distal esophageal pH monitoring. Proton-pump inhibitor medications were discontinued at least 2 weeks before testing and other reflux medications were discontinued at least 72 h before testing. The pH monitoring was performed as previously described, by positioning a glass pH electrode (Mui Scientific, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) or an antimony crystal ph electrode (Synectics Medical, Irving, TX, USA) 5 cm above the manometrically measured upper border of the LES.21 The electrode was connected to a digital recording device (Microdigitrapper, Synectics Medical, Irving, TX, USA) and pH continually monitored for 24 h. The patients’ diets were limited to foods having a pH in the range 5–7. The stored data were transferred to a personal computer and analyzed using a standard software package (Multigram, Gastrosoft, Irving, TX, USA). All patients had abnormal esophageal acid exposure, with an esophageal pH less than 4 for more than 4.4% of the total study period.21

Esophageal exposure to duodenal juice was measured using a fiberoptic probe designed to detect bilirubin by spectrophotometry at 453 nm, the specific wavelength for absorption of bilirubin (Bilitec 2000, Medtronic Synectics, Shoreview, MN, USA).22 The probe was passed transnasally and positioned at the same level as the pH electrode. Twenty-four-hour absorbance data were recorded on a portable optoelectric data logger and analyzed with a software program (Multigram, Gastrosoft, Irving, TX, USA). Bilirubin exposure was quantified as the percentage of time above an absorbance threshold of 0.2. The upper limit of the normal range for bilirubin exposure was 1.7% of the total time above an absorbance threshold of 0.2.22 Patient diets were restricted to three meals per day with no foods with an absorbance similar to that of bilirubin.

Operative Technique

Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication was performed as previously described.23 Important technical elements included crural and hiatal dissection, crural closure, and complete fundic mobilization by division of the short gastric vessels. A 2-cm loose fundoplication was constructed over a 60-Fr bougie by enveloping the distal esophagus with the anterior and posterior walls of the gastric fundus so that the anterior and posterior fundic lips met at the right lateral position on the esophagus.

Statistical Analysis

Fisher’s exact test was used to compare proportions between two groups and the linear-by-linear chi-square test was used to compare proportions between more than two groups. Continuous data were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test for two groups and the Kruskal–Wallis test for more than two groups. All P values are two-sided. SPSS version 10.0.5 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. All values are shown as median with (interquartile range) or as number of patients with (percentage).

Results

After excluding patients according to the criteria listed above, the study population consisted of 160 patients. The number of patients in each GERD category and demographic data are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the patients in the four GERD categories for either age (P value for all groups 0.86, chi-square test) or sex (P value for all groups 0.19, chi-square test). There were also no significant differences between any two individual groups for these factors. The mean follow-up period was 36.7 months for all 160 patients (median 30 months, range 12–92 months). The duration of follow-up was significantly longer for BE patients compared to patients in any of the other groups but was not significantly different between any of the other three patient groups (Table 1 legend).

Preoperative Evaluation

Symptoms

Preoperative symptom results are shown in Table 2. The only significant differences were that a higher proportion of patients with severe ERD had moderately severe or severe regurgitation compared to patients with mild ERD (P = 0.05), and moderately severe or severe dysphagia was significantly more prevalent among patients with BE compared to patients with NERD (P = 0.013, both Fisher’s exact test).

Hiatal Hernia

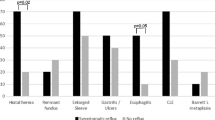

Hiatal hernia was present in 107 (66.9%) of the 160 patients. As shown in Table 3, hernia was significantly more prevalent in patients with either severe ERD or BE compared to those with either mild ERD or NERD.

Stationary Manometry

Patients with either BE or severe ERD had significantly lower LES resting pressures than patients with NERD or mild ERD (Table 3). Similarly, a hypotensive LES was more frequently found in patients with BE (30/44 patients (68.2%)) compared to patients with either NERD (14/39 (35.9%), P = 0.005) or mild ERD (16/42 (38.1%), P = 0.009, both Mann–Whitney U test). As for BE, most (19/35 (54.3%)) patients with severe ERD also had a hypotensive LES.

Regardless of group, most patients had a mechanically defective LES with one or more of the factors hypotensive LES, short total LES length, or short intra-abdominal LES length being present. A mechanically defective LES was present in a higher proportion of patients with severe ERD or BE patients (80.0% and 77.3%, respectively) compared to patients with NERD or mild ERD (56.4% and 59.5%, respectively, P = 0.046 for NERD versus severe ERD, Mann–Whitney U test).

Distal Esophageal pH and Bilirubin Exposure

As required for study entry, all patients had GERD, defined by abnormally high distal esophageal acid exposure on ambulatory pH monitoring. Distal esophageal acid exposure, measured as the total percent time the pH was less than 4 during the study period, was significantly higher in patients with either severe ERD or BE compared to patients with either NERD or mild ERD (see Table 3). Furthermore, all other measures of acid reflux (upright % time, supine % time, number of reflux episodes, number of reflux episodes longer than 5 min, duration of longest reflux episode, and composite (DeMeester) score) were significantly more abnormal in patients with BE compared to patients with either NERD or mild ERD (data not shown). Five acid reflux measures were also more severe in the BE group compared to the severe ERD group, with only the number of reflux episodes and duration of longest episode not significantly different (data not shown). Four of the seven acid reflux measures were also significantly more abnormal in patients with severe ERD compared to NERD patients (data not shown). Only the supine percent time was significantly different in the NERD and mild ERD groups, being higher in the mild ERD group (data not shown).

As shown in Table 3, there was a progressive increase in median DeMeester score with increasing mucosal injury, from NERD to mild ERD, severe ERD, and BE. The score was significantly different between all groups except the NERD and mild ERD groups and in five of the six comparisons shown in Table 3. The total percent time was significantly different in four of the six comparisons (Table 3). These results, although prespecified, have not been adjusted to take into account multiple comparisons and therefore need to be validated in further studies.

Bilirubin exposure was measured in 92 (56.8%) patients. Bile reflux, as measured by the percentage of time that absorbance at the wavelength of bilirubin was above the 0.2 threshold, was significantly higher in patients with BE (median 13.1, interquartile range 20.3) than in patients with either mild ERD (median 0.3 (14.3)) or severe ERD (2.8 (18.7), P = 0.013 and 0.021, respectively, Mann–Whitney test). Abnormally high esophageal bile exposure was present in a considerably higher proportion of BE patients (23/29 patients (79.3%)) compared to the other groups of patients (NERD 10/19 patients (52.6%), mild ERD 10/22 patients (45.5%), severe ERD 10/20 patients (50%)), but this difference was significant only for the comparison of BE versus mild ERD patients (P = 0.018, Fisher’s exact test).

Postoperative Evaluation

The postoperative results are shown in Table 4. There were no significant differences in the prevalence of any of the symptoms heartburn, regurgitation, or dysphagia among any groups.

Discussion

This study documents the clinical presentation, pathophysiologic features, and response to surgical therapy in patients at different stages of the spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux disease. We included only patients with abnormal distal esophageal acid exposure shown on ambulatory pH monitoring, thus reducing the risk of studying patients whose symptoms were not reflux-related. The patients were classified using their index endoscopy report and antireflux medication history. Patients who received acid suppressant medication therapy prior to index endoscopy showing NERD were excluded because of the effect of these medications in healing erosive disease and the consequent inability to distinguish whether these patients had NERD or healed ERD.

We believe that this study includes patients with true NERD who had not received antireflux medications prior to endoscopy at USC. The availability of these patients in a surgery study reflects the probably unusual referral basis of the USC Foregut Surgery Division in that our patient base includes some patients with reflux symptoms who are referred by their family physician directly to this unit rather than through a gastroenterologist. All patients were contacted, increasing our confidence in their classification, but we acknowledge it is not possible to be certain about the pre-endoscopy medication use of all patients because patients have an imperfect recall of their medication history and the referral correspondence can be incomplete. Similarly, we acknowledge in this retrospective study that the patients with persistent esophagitis despite medical therapy may have received an inadequate dosage or not been fully compliant, although the significant anatomical and physiological differences between the “healed esophagitis” and “persistent esophagitis” patient groups (Fig. 1) indicate that these groups differ in the mechanical properties of their antireflux barrier rather than merely in the dose of antireflux medication received.

An important finding of our study was that the preoperative mechanical factors hiatus hernia, LES resting pressure, and LES lengths were significantly more impaired in patients with severe ERD and BE compared to those with mild ERD and NERD. Esophageal acid and bile reflux also tended to be worse in the more severe GERD categories. It is well recognized that hiatal hernia is present in most patients with BE, and a lower frequency of hernia in patients with NERD has been reported.4,24,25 In a large case control study, the presence and size of hernia was strongly associated with risk of developing high grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma in patients with BE.26 Hiatal hernia has also be identified as an important factor for the development of ERD in patients with NERD. In a longitudinal study of 47 patients with NERD who underwent annual endoscopy for 5 years, hiatal hernia was a highly significant risk factor for the development of ERD.27

Our study provides further support for the importance of the length as well as the resting pressure of the LES in the etiology of GERD.28 Most of the patients, all of whom had abnormal esophageal acid exposure, had a mechanically defective LES because of either a low resting pressure or a short total or intra-abdominal LES length. The LES tended to be more frequently and more severely defective, with significantly lower LES pressures in particular, in patients with severe ERD or BE compared to those with mild ERD or NERD. As with hiatal hernia, similarly good outcomes are provided by fundoplication regardless of GERD category because the operation recreates a mechanically competent high pressure zone.

Our findings suggest that the endoscopic extent of mucosal injury reflects, and is likely to result from, the extent of mechanical abnormality at the gastroesophageal barrier and the consequent severity of gastroesophageal reflux. Furthermore, they suggest that progression to severe GERD usually requires the development of a hiatal hernia and a defective LES. This hypothesis is supported by a study from Northwestern University in which regression analysis was used to model the major risk factors for ERD in patients with symptomatic GERD. Similar to our findings, the authors reported that hiatal hernia size and LES pressure are the dominant determinants of esophagitis presence and severity.29

Several studies have found similar quality of life and symptom severity scores for patients with ERD and NERD.4,24,30,31 Consistent with this, the symptom presentation for patients with NERD was not significantly different to that for patients with ERD in this study. The severity of reflux symptoms in patients with NERD indicates that these patients have significant illness and the same need for effective treatment as patients with ERD or BE. Patients with severe ERD or BE tended to have more severe regurgitation and dysphagia, which corresponds with the worse reflux and higher prevalence of hernia in these groups. A high prevalence of dysphagia among patients with BE has been noted previously.32

As expected, patients with BE had the most severe gastroesophageal reflux. All measures of acid reflux were significantly more abnormal in patients with BE compared to either NERD or mild ERD patients. Patients with NERD tended to have less severe reflux than patients with ERD, especially those with severe ERD. This correlates with the observation that the severity of esophagitis correlates with amount of acid exposure33 and similar findings have been reported by others.25 The composite (DeMeester) score, which includes all the acid reflux measures in a weighted calculation of reflux severity, discriminated most clearly between the different GERD stages in this and a similar study.34

We have presented the findings without applying a correction for multiple comparisons; thus, one explanation is that they are false positive results due to chance alone. However, we observed consistent positive findings for different variables that are known to share an association (e.g., hernia and pH exposure), reducing the likelihood of this explanation. Furthermore, the findings are consistent with those expected from the large number of previous studies that have examined the influence of mechanical factors in the etiology of GERD. Even if the most conservative (Bonferroni) correction is applied to take into account the multiple (20 comparisons, corrected P < 0.0025) analyses performed in the analysis with the largest number of comparisons (Table 3), although fewer findings would be classified as statistically significant, the same principal conclusions apply.

All patients underwent a circumferential (Nissen) laparoscopic fundoplication and they were all contacted for this study at least 1 year after operation. We found similarly excellent symptom control in all patient groups, with no significant differences in outcome according to the stage of GERD. In contrast, consistently and significantly worse outcomes are reported for medical treatment for NERD compared to erosive disease.16–18 Lind et al., for example, documented complete symptom resolution in only 46% of NERD patients using 20 mg omeprazole daily for 4 weeks, and satisfaction with therapy was reported by only two thirds of patients.35 In a pooled data study of 2,458 patients who received differing but standard PPI doses, complete heartburn resolution was achieved in only 63% of patients at the end of 4 weeks’ treatment.36

The results for surgery for patients with NERD in this and other surgery studies15,34,37 are far superior to those for medical PPI therapy. In a study of 89 patients with NERD who underwent laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, the improvement in quality of life, as measured using the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index tool, was significantly greater in those with NERD compared to patients with erosive esophagitis because quality of life was more impaired preoperatively in the NERD group.37 At 5 years after surgery, quality of life in both NERD and ERD patient groups was comparable to healthy controls.37

The favorable results for surgical therapy in these and the current study may be partly explained by the fact that the patients without erosive esophagitis all had pH study proven reflux disease.15,34,37 We and others have previously reported better postfundoplication outcomes in patients with abnormal distal esophageal acid exposure compared to patients with normal pH study results,38,39 and the surgeon should be wary of operating on patients with no mucosal injury and acid reflux within the normal range. These patients are diagnosed with GERD by correlating symptoms with reflux events (positive symptom index)40 or by demonstrating relief of symptoms with a test course of antacid or acid suppressant therapy. There is evidence that esophageal visceral hypersensitivity, sustained esophageal contractions, and abnormal tissue resistance41 may be involved in causing symptoms in patients with minimal acid reflux, but stress,42 psychological,43,44 and psychiatric45 illness may also be factors in the these patients with “functional heartburn” or the “hypersensitive esophagus”.40,46,47

Several studies have shown that NERD, ERD, and BE are not separate diseases but part of a spectrum of GERD.1,8 As is typical of a spectrum disease, patients can progress and regress to and from different endoscopic stages. Our results suggest that, as well as being a spectrum disease, GERD can also be usefully regarded as a categorical disease that includes the two categories mild (NERD and mild ERD) and severe (severe ERD and BE) GERD. In support of categorizing GERD as mild and severe disease, the ProGERD study reported that mild erosive esophagitis (Los Angeles classification grade A or B) behaved in a similar way to NERD.

Conclusions

The spectrum of GERD includes NERD, mild and severe ERD, and BE. The clinical presentation is similar at different stages of this spectrum, although patients with severe ERD or BE may have more severe regurgitation or dysphagia. The stage of disease correlates well with the mechanical and anatomic features of the gastroesophageal reflux barrier, with hiatal hernia and a hypotensive lower esophageal sphincter significantly more prevalent in patients with severe ERD or BE. Nissen fundoplication, which reduces the hernia and augments the lower esophageal high pressure zone, provides similarly good or excellent results, regardless of the endoscopic appearance, in patients with all stages of GERD.

References

Pace F, Pallotta S, Vakil N. Gastroesophageal reflux disease is a progressive disease. Dig Liver Dis 2007;39(5):409–414. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2006.11.015.

Trimble KC, Douglas S, Pryde A, Heading RC. Clinical characteristics and natural history of symptomatic but not excess gastroesophageal reflux. Dig Dis Sci 1995;40(5):1098–1104. doi:10.1007/BF02064206.

Jones RH, Hungin APS, Phillips J, Mills JG. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in primary care in Europe: clinical presentation and endoscopic findings. Eur J Gen Pract 1995;1:149–154.

Carlsson R, Dent J, Watts R, et al. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in primary care: an international study of different treatment strategies with omeprazole. International GORD Study Group. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1998;10(2):119–124. doi:10.1097/00042737-199802000-00004.

Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, et al. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45(2):172–180.

Kulig M, Leodolter A, Vieth M, et al. Quality of life in relation to symptoms in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease—an analysis based on the ProGERD initiative. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003;18(8):767–776. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01770.x.

Labenz J, Jaspersen D, Kulig M, et al. Risk factors for erosive esophagitis: a multivariate analysis based on the ProGERD study initiative. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99(9):1652–1656. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30390.x.

Labenz J, Nocon M, Lind T, et al. Prospective follow-up data from the ProGERD study suggest that GERD is not a categorial disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101(11):2457–2462.

Bajbouj M, Reichenberger J, Neu B, et al. A prospective multicenter clinical and endoscopic follow-up study of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Z Gastroenterol 2005;43(12):1303–1307. doi:10.1055/s-2005-858874.

Peters JH, DeMeester TR, Crookes P, et al. The treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease with laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: prospective evaluation of 100 patients with “typical” symptoms. Ann Surg 1998;228(1):40–50. doi:10.1097/00000658-199807000-00007.

Trus TL, Laycock WS, Waring JP, et al. Improvement in quality of life measures after laparoscopic antireflux surgery. Ann Surg. 1999;229(3):331–336. doi:10.1097/00000658-199903000-00005.

Lord RV. Antireflux surgery for Barrett’s oesophagus. ANZ J Surg 2003;73(4):234–246. doi:10.1046/j.1445-1433.2003.02569.x.

Zaninotto G, Portale G, Costantini M, et al. Long-term results (6–10 years) of laparoscopic fundoplication. J Gastrointest Surg 2007;11(9):1138–1145. doi:10.1007/s11605-007-0195-y.

Morgenthal CB, Shane MD, Stival A, et al. The durability of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: 11-year outcomes. J Gastrointest Surg 2007;11(6):693–700. doi:10.1007/s11605-007-0161-8.

Watson DI, Foreman D, Devitt PG, Jamieson GG. Preoperative endoscopic grading of esophagitis versus outcome after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Am J Gastroenterol 1997;92(2):222–225.

Fass R. Erosive esophagitis and nonerosive reflux disease (NERD): comparison of epidemiologic, physiologic, and therapeutic characteristics. J Clin Gastroenterol 2007;41(2):131–137. doi:10.1097/01.mcg.0000225631.07039.6d.

Dean BB, Gano AD Jr, Knight K, et al. Effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors in nonerosive reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2(8):656–664. doi:10.1016/S1542-3565(04)00288-5.

van Pinxteren B, Numans ME, Bonis PA, Lau J. Short-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists and prokinetics for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-like symptoms and endoscopy negative reflux disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;3:CD002095.

Ollyo JB, Lang F, Fontolle CH, Monnier PH. Savary’s new endoscopic grading of reflux oesophagitis: a simple, reproducible, logical, complete and useful classification. Gastroenterology 1990;89:A100.

Zaninotto G, DeMeester TR, Schwizer W, et al. The lower esophageal sphincter in health and disease. Am J Surg 1988;155(1):104–111. doi:10.1016/S0002-9610(88)80266-6.

Jamieson JR, Stein HJ, DeMeester TR, et al. Ambulatory 24-h esophageal pH monitoring: normal values, optimal thresholds, specificity, sensitivity, and reproducibility. Am J Gastroenterol 1992;87(9):1102–1111.

Kauer WK, Burdiles P, Ireland AP, et al. Does duodenal juice reflux into the esophagus of patients with complicated GERD? Evaluation of a fiberoptic sensor for bilirubin. Am J Surg 1995;169(1):98–103. doi:10.1016/S0002-9610(99)80116-0.

Lord RVN, DeMeester TR. Reflux disease and hiatal hernia. Oxford Textbook of Surgery. vol. 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000, pp 1239–1262.

Venables TL, Newland RD, Patel AC, et al. Omeprazole 10 milligrams once daily, omeprazole 20 milligrams once daily, or ranitidine 150 milligrams twice daily, evaluated as initial therapy for the relief of symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in general practice. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997;32(10):965–73. doi:10.3109/00365529709011211.

Frazzoni M, De Micheli E, Savarino V. Different patterns of oesophageal acid exposure distinguish complicated reflux disease from either erosive reflux oesophagitis or non-erosive reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003;18(11–12):1091–1098. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01768.x.

Avidan B, Sonnenberg A, Schnell TG, et al. Hiatal hernia size, Barrett’s length, and severity of acid reflux are all risk factors for esophageal adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97(8):1930–1936. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05902.x.

Kawanishi M. Will symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease develop into reflux esophagitis? J Gastroenterol 2006;41(5):440–443. doi:10.1007/s00535-006-1791-4.

DeMeester TR, Peters JH, Bremner CG, Chandrasoma P. Biology of gastroesophageal reflux disease: pathophysiology relating to medical and surgical treatment. Annu Rev Med 1999;50:469–506. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.50.1.469.

Jones MP, Sloan SS, Rabine JC, et al. Hiatal hernia size is the dominant determinant of esophagitis presence and severity in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96(6):1711–1717. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03926.x.

Havelund T, Lind T, Wiklund I, et al. Quality of life in patients with heartburn but without esophagitis: effects of treatment with omeprazole. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94(7):1782–1789. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01206.x.

Tew S, Jamieson GG, Pilowsky I, Myers J. The illness behavior of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease with and without endoscopic esophagitis. Dis Esophagus 1997;10(1):9–15.

DeMeester SR, DeMeester TR. Columnar mucosa and intestinal metaplasia of the esophagus: fifty years of controversy. Ann Surg 2000;231(3):303–321. doi:10.1097/00000658-200003000-00003.

Masclee AA, de Best AC, de Graaf R, et al. Ambulatory 24-hour pH-metry in the diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Determination of criteria and relation to endoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol 1990;25(3):225–230.

Bammer T, Freeman M, Shahriari A, et al. Outcome of laparoscopic antireflux surgery in patients with nonerosive reflux disease. J Gastrointest Surg 2002;6(5):730–737. doi:10.1016/S1091-255X(02)00042-2.

Lind T, Havelund T, Carlsson R, et al. Heartburn without oesophagitis: efficacy of omeprazole therapy and features determining therapeutic response. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997;32(10):974–979. doi:10.3109/00365529709011212.

Talley NJ, Armstrong D, Junghard O, et al. Predictors of treatment response in patients with non-erosive reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;24(2):371–376. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02983.x.

Kamolz T, Granderath FA, Schweiger UM, Pointner R. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication in patients with nonerosive reflux disease. Long-term quality-of-life assessment and surgical outcome. Surg Endosc 2005;19(4):494–500. doi:10.1007/s00464-003-9267-6.

Campos GM, Peters JH, DeMeester TR, et al. Multivariate analysis of factors predicting outcome after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. J Gastrointest Surg 1999;3:292–300. doi:10.1016/S1091-255X(99)80071-7.

Khajanchee YS, Hong D, Hansen PD, Swanstrom LL. Outcomes of antireflux surgery in patients with normal preoperative 24-hour pH test results. Am J Surg 2004;187(5):599–603. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.01.010.

Shi G, Bruley dV, Scarpignato C, et al. Reflux related symptoms in patients with normal oesophageal exposure to acid. Gut 1995;37(4):457–464. doi:10.1136/gut.37.4.457.

Barlow WJ, Orlando RC. The pathogenesis of heartburn in nonerosive reflux disease: a unifying hypothesis. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(3):771–778. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2004.08.014.

Bradley LA, Richter JE, Pulliam TJ, et al. The relationship between stress and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux: the influence of psychological factors. Am J Gastroenterol 1993;88(1):11–19.

Johnston BT, Lewis SA, Collins JS, et al. Acid perception in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease is dependent on psychosocial factors. Scand J Gastroenterol 1995;30(1):1–5. doi:10.3109/00365529509093228.

Norton GR, Norton PJ, Asmundson GJ, et al. Neurotic butterflies in my stomach: the role of anxiety, anxiety sensitivity and depression in functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Psychosom Res 1999;47(3):233–240. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(99)00032-X.

Avidan B, Sonnenberg A, Giblovich H, Sontag SJ. Reflux symptoms are associated with psychiatric disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001;15(12):1907–1912. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01131.x.

Trimble KC, Pryde A, Heading RC. Lowered oesophageal sensory thresholds in patients with symptomatic but not excess gastro-oesophageal reflux: evidence for a spectrum of visceral sensitivity in GORD. Gut 1995;37(1):7–12. doi:10.1136/gut.37.1.7.

Achem SR. Endoscopy-negative gastroesophageal reflux disease. The hypersensitive esophagus. Gastro Clin Nth Am 1999;28(4):893–904. doi:10.1016/S0889-8553(05)70096-0.

Support

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Lord, R.V.N., DeMeester, S.R., Peters, J.H. et al. Hiatal Hernia, Lower Esophageal Sphincter Incompetence, and Effectiveness of Nissen Fundoplication in the Spectrum of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. J Gastrointest Surg 13, 602–610 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-008-0754-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-008-0754-x