Abstract

I describe how our understanding of some of the central principles long held dear by most (but certainly not all) criminal theorists may have to be interpreted (or re-interpreted) in light of the need to devise lenient responses (that may or may not amount to punishments) for low-level offenders. Several of the most plausible suggestions for how to deal with minor infractions force us to take seriously some ideas that many legal philosophers have tended to resist elsewhere. I briefly touch upon four topics: (1) whether informal (that is, non-state responses) can substitute for or count against the appropriate state sanction; (2) the significance of repeat offending for sentencing; (3) whether punishment for culpable public wrongdoing has intrinsic value; and (4) the scope of police powers in a liberal democratic state. The context for this discussion is R. A. Duff’s insightful examination of whether and under what conditions we should criminalize a public wrong or respond to it in some other manner.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Among the most recent of many impressive books is Rachel Elise Barkow: Prisoners of Politics: Breaking the Cycle of Mass Incarceration (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2019).

I argue that no offenses of drug use are justified in Douglas Husak: Drugs and Rights (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992). My thoughts on the rationale for legalizing drug use have remained largely unchanged in the 26 years since its publication. Still, marijuana offenses are the most sensible place to begin in a more comprehensive plan of drug reform.

See John P. Pfaff: Locked In: The True Causes of Mass Incarceration—and How to Achieve Real Reform (New York: Basic Books, 2017).

This claim must be qualified in many ways. In particular, both penal theorists and members of the public often contend that our state is too lenient in a number of areas, most notably sex offenses and white collar crimes. In addition, many would prefer to impose further gun controls. Generally, see Benjamin Levin: “The Consensus Myth in Criminal Justice Reform,” 117 Michigan Law Review 259 (2018).

I do, however, hope to undermine the misconception that we retributivists are partly to blame for fueling our proclivity to punish in the first place, and that we are also apt to derail any progress that might be made in the future. See the worry expressed by Barkow: op.cit. Note 1, p. 205.

I describe several of these problems in Douglas Husak: “The Metric of Punishment Severity: A Puzzle for the Principle of Proportionality,” in Michael Tonry, ed.: Of One-Eyed and Toothless Miscreants: Making the Punishment Fit the Crime? (Oxford: Oxford University Press, forthcoming, 2019).

See Andrew von Hirsch: Past or Future Crimes (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1985).

Alexandra Natapoff: Punishment Without Crime: How Our Massive Misdemeanor System Traps the Innocent and Makes America More Unequal (New York: Basic Books, 2018), p. 3.

Reliable numbers are hard to find, but approximately 13 million misdemeanor cases are filed each year. Id., p. 41.

I generally resist using the label felony to refer to relatively serious offenses and misdemeanor to refer to those that are not so serious. The use of these terms invites the misconception that the seriousness of proscribed conduct differs in kind and not merely in degree. But these labels have never been defined consistently and are applied quite differently to offenses throughout various Anglo-American jurisdictions.

See Franklin E. Zimring: The City that Became Safe: New York’s Lessons for Urban Crime and Its Control (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

Ray Kelly: Vigilance (New York: Hachette, 2015).

See Bernard E. Harcourt: Illusion of Order: The False Promise of Broken Windows Policing (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001).

The widespread use of “stop, question and frisk” reached its zenith in 2011 with 685,724 stops.

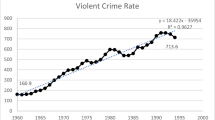

New York Department of Criminal Justice Services (DCJS), 1990 to 2015.

For an additional exception, see Irene Oritseweyinmi Joe: "Rethinking Misdemeanor Neglect," 64 U.C.L.A. Law Review 738 (2017).

Issa Kohler-Hausmann: Misdemeanorland: Criminal Courts and Social Control in an Era of Broken Windows Policing (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018), p. 265.

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Id., p. 278.

Id.

Id., pp. 280–292.

Some alternatives are described by Hadassa Noorda: “Exprisonment: Deprivations of Liberty on the Street and at Home,” (forthcoming). They include area restrictions, revocation of licenses, GPS bracelets, house searches, and the disenfranchisement of voter rights.

Fare evasion on the buses and subways of New York City cost the Metropolitan Transportation System approximately $225 million each year, necessitating fare increases across the board. One in five bus riders do not pay their fare. See Emma G. Fitzsimmons and Edgar Sandoval: “1 in 5 Bus Riders in New York City Evade the Fare, Far Worse Than Elsewhere,” New York Times (April 13, 2019).

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/13/nyregion/mta-bus-riders-fare-beaters.html.

op.cit. Note 18, p. 280.

Id., p. 281.

Id., p. 282.

Even vigilantism has been common throughout history, although the responses Duff envisages probably do not merit this description. See Paul H. Robinson and Sarah M. Robinson: Shadow Vigilantes (New York: Random House, 2018).

See Douglas Husak: “State Authority to Punish Crime,” in Chad Flanders and Zachary Hoskins, eds.: New Philosophy of Criminal Law (Rowman and Littlefield, 2016), p. 97.

See Adam J. Kolber: “The Subjective Experience of Punishment,” 109 Columbia Law Review 182 (2009).

See Douglas Husak: “Already Punished Enough,” in Douglas Husak, ed.: The Philosophy of Criminal Law: Selected Essays (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 433.

See Alexes Harris: A Pound of Flesh: Monetary Sanctions as Punishment for the Poor (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2016).

Kohler-Hausmann: Op. Cit. Note 17, p. 69.

Id., Chapter Five.

Malcolm Feeley: The Process Is the Punishment: Handling Cases in a Lower Criminal Court (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1979).

op.cit. Note 17, p. 74.

See Julian V. Roberts and Andrew von Hirsch, eds.: Previous Convictions at Sentencing (Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2010).

Op.cit. note 17, p. 264.

Id., p. 120.

James B. Jacobs: The Eternal Criminal Record (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015).

See Zachary Hoskins: Beyond Punishment? A Normative Account of the Collateral Consequences of Conviction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

See Adam J. Kolber: “The Time-Frame Challenge to Retributivism,” (forthcoming).

See Andrew von Hirsch: “Proportionality and Progressive Loss of Mitigation: Further Reflections,” in Roberts and Von Hirsch, op.cit. Note 36, p. 1.

Victor Tadros uses different grounds to create problems for retributivism by reference to minor offenses in “The Wrong and the Free,” in Kimberly Kessler Ferzan and Stephen J. Morse, eds.: Legal, Moral and Metaphysical Truths: The Philosophy of Michael S. Moore (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), p. 79.

See Mitchell M. Berman: “Modest Retributivism,” in Ferzan and Morse, id., p. 35.

See Michael S. Moore: “Closet Retributivism” in his Placing Blame (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997), p. 83.

Suffering may not be the best candidate for a desert object, that is, for what it is that culpable wrongdoers deserve. For example, perhaps they deserve that their lives go less well. See Mitchell N. Berman: “Rehabilitating Retributivism,” 32 Law and Philosophy 83 (2013).

But see Emily Bazelon: Charged: The New Movement to Transform Prosecution and End Mass Incarceration (2019).

Duff, to his credit, talks quite a bit about the police throughout op.cit. Note 18. However, he does not address the general topic of what powers police should be granted.

See Douglas Husak: “Police and Racial Discrimination: Throwing out the Baby with the Bath Water,” in Molly Gardner and Michael Weber, eds.: The Ethics of Policing and Imprisonment (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), p. 87.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Thanks to members of the conference on R. A. Duff’s The Realm of Criminal Law at Rutgers University on May 10–11, 2019.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Husak, D. Criminal Law at the Margins. Criminal Law, Philosophy 14, 381–393 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11572-019-09505-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11572-019-09505-9