Abstract

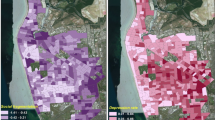

Depression prevalence is known to vary by individual factors (gender, age, race, medical comorbidities) and by neighborhood factors (neighborhood deprivation). However, the combination of individual- and neighborhood-level data is rarely available to assess their relative contribution to variation in depression across neighborhoods. We geocoded depression diagnosis and demographic data from electronic health records for 165,600 patients seen in two large health systems serving the Denver population (Kaiser Permanente and Denver Health) to Denver’s 144 census tracts, and combined these data with indices of neighborhood deprivation obtained from the American Community Survey. Non-linear mixed models examined the relationships between depression rates and individual and census tract variables, stratified by health system. We found higher depression rates associated with greater age, female gender, white race, medical comorbidities, and with lower rates of home owner occupancy, residential stability, and higher educational attainment, but not with economic disadvantage. Among the Denver Health cohort, higher depression rates were associated with higher crime rates and a lower percent of foreign born residents and single mother households. Our findings suggest that individual factors had the strongest associations with depression. Neighborhood risk factors associated with depression point to low community cohesion, while the role of education is more complex. Among the Denver Health cohort, language and cultural barriers and competing priorities may attenuate the recognition and treatment of depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–27.

Murray CJL, Lopez AD, World Health Organization WB. The Global Burden of Disease: a Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability from Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. Geneva: Harvard School of Public Health, World Health Organization, World Bank, Boston, MA 1996.

Chapman DP, Perry GS, Strine TW. The vital link between chronic disease and depressive disorders. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2(1):A14.

Singh GK. Area deprivation and widening inequalities in US mortality, 1969-1998. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(7):1137–43.

Messer LC, Laraia BA, Kaufman JS, Eyster J, Holzman C, Culhane J, et al. The development of a standardized neighborhood deprivation index. J Urban Health. 2006;83(6):1041–62.

Jackson JS, Knight KM, Rafferty JA. Race and unhealthy behaviors: chronic stress, the HPA axis, and physical and mental health disparities over the life course. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(5):933–9.

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey (ACS). 2014; Available from: https://www.census.gov/regions/denver/www/programs_surveys/surveys/acs.php. Accessed 12/07/2016.

Davidson A. Colorado’s Health Observation Regional Data Service (CHORDS). Paper Presented at: PopMedNet User Conference. Boston, MA: Simmons College, 2015.

PopMedNet. Distributed query tool: user’s guide. Based on version 50 2015; Available from: https://popmednet.atlassian.net/wiki/display/DOC/PopMedNet+User%27s+Guide. Accessed 12/13/2016.

Platt R, Carnahan RM, Brown JS, Chrischilles E, Curtis LH, et al. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s mini-sentinel program: status and direction. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(Suppl 1):1–8.

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). (2016) The National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORnet). Available from: http://www.pcornet.org. Accessed 12/07/2016.

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–9.

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey (ACS). 2015; Available from: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. Accessed 12/07/2016.

Mair C, Diez Roux AV, Galea S. Are neighbourhood characteristics associated with depressive symptoms? A review of evidence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(11):940–6. 948 p following 946

Matheson FI, Moineddin R, Dunn JR, Creatore MI, Gozdyra P, Glazier RH. Urban neighborhoods, chronic stress, gender and depression. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(10):2604–16.

Galea S, Ahern J, Nandi A, Tracy M, Beard J, Vlahov D. Urban neighborhood poverty and the incidence of depression in a population-based cohort study. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(3):171–9.

Ploubidis GB, Grundy E. Later-life mental health in Europe: a country-level comparison. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64(5):666–76.

Nicholson A, Pikhart H, Pajak A, Malyutina S, Kubinova R, et al. Socio-economic status over the life-course and depressive symptoms in men and women in Eastern Europe. J Affect Disord. 2008;105(1–3):125–36.

World Health Organization and Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. Social determinants of mental health. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2014.

Beard JR, Tracy M, Vlahov D, Galea S. Trajectory and socioeconomic predictors of depression in a prospective study of residents of New York City. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18(3):235–43.

Fryers T, Melzer D, Jenkins R, Brugha T. The distribution of the common mental disorders: social inequalities in Europe. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2005;1:14.

McManus S, Meltzer H, Brugha T, Bebbington P, Jenkins R. (2009) Adult psychiatric morbidity in England, 2007: results of a household survey. National Health Service (NHS), Leeds, England.

Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S, Lin S, Scuderi B, Turner N, et al. The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014. JAMA. 2016;315(16):1750–66. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.4226.

Hudson DL, Karter AJ, Fernandez A, Parker M, Adams AS, Schillinger D, et al. Differences in the clinical recognition of depression in diabetes patients: the diabetes study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(5):344–52.

Coleman KJ, Stewart CC, Waitzfelder B, Zeber JE, Morales LS, Ahmed AT, et al. Racial-ethnic differences in psychiatric diagnoses and treatment across 11 Health Care Systems in the Mental Health Research Network. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67:749–57. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201500217.

Curry A, Latkin C, Davey-Rothwell M. Pathways to depression: the impact of neighborhood violent crime on inner-city residents in Baltimore, Maryland, USA. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(1):23–30.

Colorado Cross-Agency Collaborative. Measuring behavioral health: fulfilling Colorado’s commitment to become the healthiest state. Denver, Colorado: Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, Colorado Department of Human Services—Office of Behavioral Health, Department of Health Care Policy and Financing; 2013.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by AHRQ grant #5R24HS0122143.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Beck, A., Davidson, A.J., Xu, S. et al. A Multilevel Analysis of Individual, Health System, and Neighborhood Factors Associated with Depression within a Large Metropolitan Area. J Urban Health 94, 780–790 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-017-0190-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-017-0190-x