Abstract

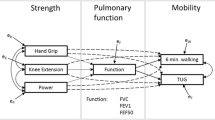

Computational models have been used extensively to assess diseases and disabilities effects on musculoskeletal system dysfunction. In the current study, we developed a two degree-of-freedom subject-specific second-order task-specific arm model for characterizing upper-extremity function (UEF) to assess muscle dysfunction due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Older adults (65 years or older) with and without COPD and healthy young control participants (18 to 30 years) were recruited. First, we evaluated the musculoskeletal arm model using electromyography (EMG) data. Second, we compared the computational musculoskeletal arm model parameters along with EMG-based time lag and kinematics parameters (such as elbow angular velocity) between participants. The developed model showed strong cross-correlation with EMG data for biceps (0.905, 0.915) and moderate cross-correlation for triceps (0.717, 0.672) within both fast and normal pace tasks among older adults with COPD. We also showed that parameters obtained from the musculoskeletal model were significantly different between COPD and healthy participants. On average, higher effect sizes were achieved for parameters obtained from the musculoskeletal model, especially for co-contraction measures (effect size = 1.650 ± 0.606, p < 0.001), which was the only parameter that showed significant differences between all pairwise comparisons across the three groups. These findings suggest that studying the muscle performance and co-contraction, may provide better information regarding neuromuscular deficiencies compared to kinematics data. The presented model has potential for assessing functional capacity and studying longitudinal outcomes in COPD.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Health NIO (2012) Morbidity & mortality: 2012 chart book on cardiovascular, lung, and blood diseases. Retrieved May, 15

Niewoehner DE, D Collins, and MLErbland Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group (2000) Relation of FEV1 to clinical outcomes during exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 161(4):1201–1205

Pinto-Plata V et al (2004) The 6-min walk distance: change over time and value as a predictor of survival in severe COPD. Eur Respir J 23(1):28–33

Maltais F et al (2014) An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update on limb muscle dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 189(9):e15–e62

Carter R et al (2003) 6-minute walk work for assessment of functional capacity in patients with COPD. Chest 123(5):1408–1415

Sciurba F et al (2003) Six-minute walk distance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: reproducibility and effect of walking course layout and length. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 167(11):1522–1527

Spruit MA et al (2012) Predicting outcomes from 6-minute walk distance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc 13(3):291–297

Mohler J et al (2013) In-home activity monitoring in frail elders: a new measure of function. in JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN GERIATRICS SOCIETY. WILEY-BLACKWELL 111 RIVER ST, HOBOKEN 07030–5774, NJ USA

Najafi B, MJ Mohler, and N Toosizadeh (2020) Method and system to identify frailty using body movement. Google Patents

Toosizadeh N, Mohler J, Najafi B (2015) Assessing upper extremity motion: an innovative method to identify frailty. J Am Geriatr Soc 63(6):1181–1186

Toosizadeh N et al (2017) Assessing upper-extremity motion: An innovative method to quantify functional capacity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS ONE 12(2):e0172766

Ehsani H et al (2019) Upper-extremity function prospectively predicts adverse discharge and all-cause COPD readmissions: a pilot study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 14:39

Bernard S et al (1998) Peripheral muscle weakness in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 158(2):629–634

Gosselink R, Troosters T, Decramer M (2000) Distribution of muscle weakness in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 20(6):353–360

Morris ME (2000) Movement disorders in people with Parkinson disease: a model for physical therapy. Phys Ther 80(6):578–597

Shao Q et al (2009) An EMG-driven model to estimate muscle forces and joint moments in stroke patients. Comput Biol Med 39(12):1083–1088

van Dieën JH, Cholewicki J, Radebold A (2003) Trunk muscle recruitment patterns in patients with low back pain enhance the stability of the lumbar spine. Spine 28(8):834–841

Chae J et al (2002) Muscle weakness and cocontraction in upper limb hemiparesis: relationship to motor impairment and physical disability. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 16(3):241–248

Hill AV (1938) The heat of shortening and the dynamic constants of muscle Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Ser B-Biol Sci 126(843):136–195

Huxley A (1974) Muscular contraction. J Physiol 243(1):1

Winters JM, Stark L (1987) Muscle models: what is gained and what is lost by varying model complexity. Biol Cybern 55(6):403–420

Nikooyan AA et al (2011) Development of a comprehensive musculoskeletal model of the shoulder and elbow. Med Biol Eng Compu 49(12):1425–1435

Blana D et al (2008) A musculoskeletal model of the upper extremity for use in the development of neuroprosthetic systems. J Biomech 41(8):1714–1721

Raikova R, Aladjov H (2003) The influence of the way the muscle force is modeled on the predicted results obtained by solving indeterminate problems for a fast elbow flexion. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin 6(3):181–196

Davies L, Angus R, Calverley P (1999) Oral corticosteroids in patients admitted to hospital with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 354(9177):456–460

Abdool-Gaffar M et al (2011) Guideline for the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: update. SAMJ: South Afr Med J 101(1):63–73

Travis WD et al (2013) An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 188(6):733–748

Hu X et al (2007) Variation of muscle coactivation patterns in chronic stroke during robot-assisted elbow training. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 88(8):1022–1029

Ehsani H et al (2020) Can motor function uncertainty and local instability within upper-extremity dual-tasking predict amnestic mild cognitive impairment and early-stage Alzheimer’s disease? Comput Biol Med 120:103705

Toosizadeh N et al (2019) Screening older adults for amnestic mild cognitive impairment and early-stage Alzheimer’s disease using upper-extremity dual-tasking. Sci Rep 9(1):1–11

Toosizadeh N et al (2017) Frailty assessment in older adults using upper-extremity function: index development. BMC Geriatr 17(1):117

Joseph B et al (2017) Upper-extremity function predicts adverse health outcomes among older adults hospitalized for ground-level falls. Gerontol 63(4):299–307

Toosizadeh N et al (2016) Assessing upper-extremity motion: an innovative, objective method to identify frailty in older bed-bound trauma patients. J Am Coll Surg 223(2):240–248

Hermens HJ et al (1999) European recommendations for surface electromyography. Roessingh Res Dev 8(2):13–54

Ives JC, Wigglesworth JK (2003) Sampling rate effects on surface EMG timing and amplitude measures. Clin Biomech 18(6):543–552

Merletti R et al (2002) Effect of age on muscle functions investigated with surface electromyography. Muscle Nerve: Off J Am Assoc Electrodiagnostic Med 25(1):65–76

Ehsani H et al (2019) Efficient embedding of empirically-derived constraints in the ODE formulation of multibody systems: Application to the human body musculoskeletal system. Mech Mach Theory 133:673–690

Pigeon P, Feldman AG (1996) Moment arms and lengths of human upper limb muscles as functions of joint angles. J Biomech 29(10):1365–1370

Bertsekas DP (2014) Constrained optimization and Lagrange multiplier methods. 2014: Academic press

Toosizadeh N, Haghpanahi M (2011) Generating a finite element model of the cervical spine: Estimating muscle forces and internal loads. Scientia Iranica 18(6):1237–1245

Raikova RT (2009) Investigation of the influence of the elbow joint reaction on the predicted muscle forces using different optimization functions. J Musculoskelet Res 12(01):31–43

Holzbaur KR, Murray WM, Delp SL (2005) A model of the upper extremity for simulating musculoskeletal surgery and analyzing neuromuscular control. Ann Biomed Eng 33(6):829–840

Bean JC, Chaffin DB, Schultz AB (1988) Biomechanical model calculation of muscle contraction forces: a double linear programming method. J Biomech 21(1):59–66

Raikova R (1999) About weight factors in the non-linear objective functions used for solving indeterminate problems in biomechanics. J Biomech 32(7):689–694

Parsa B, H Ehsani, and M Rostami (2013) Analyzing synergistic and antagonistic muscle behavior during elbow planar flexion-extension: entropy-assisted vs. shift-parameter criterion. in 2013 20th Iranian Conference on Biomedical Engineering (ICBME). IEEE

Chang Y-W et al (1999) Optimum length of muscle contraction. Clin Biomech 14(8):537–542

Suzuki M et al (1997) Trajectory formation of the center-of-mass of the arm during reaching movements. Neurosci 76(2):597–610

Veeger H et al (1997) Parameters for modeling the upper extremity. J Biomech 30(6):647–652

An K-N et al (1981) Muscles across the elbow joint: a biomechanical analysis. J Biomech 14(10):659–669

Hodges PW, Bui BH (1996) A comparison of computer-based methods for the determination of onset of muscle contraction using electromyography. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 101(6):511–519

Toosizadeh N et al (2017) Frailty assessment in older adults using upper-extremity function: index development. BMC Geriatr 17(1):1–7

Schaap LA, Koster A, Visser M (2013) Adiposity, muscle mass, and muscle strength in relation to functional decline in older persons. Epidemiol Rev 35(1):51–65

Buchanan TS, Shreeve DA (1996) An evaluation of optimization techniques for the prediction of muscle activation patterns during isometric tasks. J Biomech Eng 118(4):565–574

Challis JH, Kerwin D (1993) An analytical examination of muscle force estimations using optimization techniques. Proc Inst Mech Eng [H] 207(3):139–148

Bl Prilutsky (2000) Coordination of two-and one-joint muscles: functional consequences and implications for motor control. Motor control 4(1):1–44

Jiang Z, and GA Mirka (2007) Application of an entropy-assisted optimization model in prediction of agonist and antagonist muscle forces. in Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting. SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA

Lai AK, Arnold AS, Wakeling JM (2017) Why are antagonist muscles co-activated in my simulation? A musculoskeletal model for analysing human locomotor tasks. Ann Biomed Eng 45(12):2762–2774

Roh J et al (2013) Alterations in upper limb muscle synergy structure in chronic stroke survivors. J Neurophysiol 109(3):768–781

Inouye JM, Valero-Cuevas FJ (2016) Muscle synergies heavily influence the neural control of arm endpoint stiffness and energy consumption. PLoS Comput Biol 12(2):e1004737

Scovil CY, Ronsky JL (2006) Sensitivity of a Hill-based muscle model to perturbations in model parameters. J Biomech 39(11):2055–2063

Wüst RC, Degens H (2007) Factors contributing to muscle wasting and dysfunction in COPD patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2(3):289

Rennie M et al (1983) Depressed protein synthesis is the dominant characteristic of muscle wasting and cachexia. Clin Physiol 3(5):387–398

Casaburi R et al (2004) Effects of testosterone and resistance training in men with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 170(8):870–878

Van Vliet M et al (2005) Hypogonadism, quadriceps weakness, and exercise intolerance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 172(9):1105–1111

Busse M, Wiles CM, Van Deursen RWM (2005) Muscle co-activation in neurological conditions. Physical therapy reviews 10(4):247–253

Hirokawa S et al (1991) Muscular co-contraction and control of knee stability. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 1(3):199–208

Hortobágyi T, DeVita P (2006) Mechanisms responsible for the age-associated increase in coactivation of antagonist muscles. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 34(1):29–35

Potvin J, O’brien P (1998) Trunk muscle co-contraction increases during fatiguing, isometric, lateral bend exertions: possible implications for spine stability. Spine 23(7):774–780

Rosa MCN et al (2014) Lower limb co-contraction during walking in subjects with stroke: a systematic review. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 24(1):1–10

Souissi H et al (2017) Co-contraction around the knee and the ankle joints during post-stroke gait. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 54(3):380–387

Shah S et al (2013) Upper limb muscle strength & endurance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Indian J Med Res 138(4):492

Clark C et al (2000) Skeletal muscle strength and endurance in patients with mild COPD and the effects of weight training. Eur Respir J 15(1):92–97

Zattara-Hartmann MC et al (1995) Maximal force and endurance to fatigue of respiratory and skeletal muscles in chronic hypoxemic patients: the effects of oxygen breathing. Muscle Nerve: Off J Am Assoc Electrodiagnostic Med 18(5):495–502

Jakobsson P, Jorfeldt L, Brundin A (1990) Skeletal muscle metabolites and fibre types in patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), with and without chronic respiratory failure. Eur Respir J 3(2):192–196

Piazzesi G, Lombardi V (1995) A cross-bridge model that is able to explain mechanical and energetic properties of shortening muscle. Biophys J 68(5):1966–1979

Micera S, Sabatini AM, Dario P (1998) An algorithm for detecting the onset of muscle contraction by EMG signal processing. Med Eng Phys 20(3):211–215

Polkey MI et al (2013) Six-minute-walk test in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: minimal clinically important difference for death or hospitalization. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 187(4):382–386

Engelen M et al (1994) Nutritional depletion in relation to respiratory and peripheral skeletal muscle function in out-patients with COPD. Eur Respir J 7(10):1793–1797

Dolmage TE et al (1993) The ventilatory response to arm elevation of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest 104(4):1097–1100

Funding

This project was supported by an award from the National Institute of Aging (NIA) (award number: 5R21AG059202-02). The findings of this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Asghari, M., Peña, M., Ruiz, M. et al. A computational musculoskeletal arm model for assessing muscle dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Med Biol Eng Comput 61, 2241–2254 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11517-023-02823-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11517-023-02823-0