Abstract

Healthy eating adds to health and thereby contributes to a longer life, but will it also add to a happier life? Some people do not like healthy food, and since we spend a considerable amount of our life eating, healthy eating could make their life less enjoyable. Is there such a trade-off between healthy eating and happiness? Or instead a trade-on, healthy eating adding to happiness? Or do the positive and negative effects balance? If there is an effect of healthy eating on happiness, is that effect similar for everybody? If not, what kind of people profit from healthy eating happiness wise and what kind of people do not? If healthy eating does add to happiness, does it add linearly or is there some optimum for healthy ingredients in one’s diet? I considered the results published in 20 research reports on the relation between nutrition and happiness, which together yielded 47 findings. I reviewed these findings, using a new technique. The findings were entered in an online ‘findings archive’, the World Database of Happiness, each described in a standardized format on a separate ‘findings page’ with a unique internet address. In this paper, I use links to these finding pages and this allows us to summarize the main trends in the findings in a few tabular schemes. Together, the findings provide strong evidence of a causal effect of healthy eating on happiness. Surprisingly, this effect is not fully mediated by better health. This pattern seems to be universal, the available studies show only minor variations across people, times and places. More than three portions of fruits and vegetables per day goes with the most happiness, how many more for what kind of persons is not yet established.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Healthy eating, in particular a diet rich in fruit and vegetables (FV) adds to our health; primarily because it reduces our chances of contracting a number of eating related diseases (Oyebode et al. 2014; Bazzano et al. 2002; Liu et al. 2000). Since good health adds to happiness, it is likely that healthy diets will also add to happiness, but a firm connection has not been established.

In recent years, the relationship between obesity and mental states has begun to attract serious research interest (Becker et al. 2001; Rooney et al. 2013), as has the relationship between specific micro-nutrients and psychological health (Stough et al. 2011). As yet, there is little research on the relationship between nutrition and happiness.

It is worth knowing to what extent our eating habits affect our happiness. One reason is that most people are concerned about their happiness and look for ways to increase it. Most determinants of happiness are beyond our control, but what we eat is largely in our own hands. In this context, we would like to know whether there is a trade-off between healthy eating and happy living. Gains in length of life due to healthy eating may be counterbalanced by loss of satisfaction with life, as is argued in the debate on the benefits of drinking alcohol (Baum-Baicker 1985). If so, healthy eating may mean that we live longer, but not happier.

Empirical assessment of the effects of healthy eating on happiness is fraught with complications. One complication is that the effect of nutrition is probably not the same for everybody. Hence, we must identify what food pattern is optimal for what kind of person. A second problem is that happiness can influence nutrition behaviour, for example unhappiness can lead to the consumption of unhealthy comfort foods. Cause and effect must be disentangled. If a healthy diet does appear to add to happiness, then a third question arises: Is eating more healthy food always better or is there an optimum amount one should eat? For instance, is one apple a day enough to make us feel happy? Or will we feel better with four daily portions of fruit? How about small sins, such as a bar of chocolate or a daily glass of wine?

Research Questions

-

1.

Is there a trade-of or between healthy eating and happiness? Or rather a trade-on, healthy eating adding to happiness? Or do the positive and negative effects balance?

-

2.

Is this effect of healthy eating on happiness similar for everybody? If not, what kind of people profit from healthy eating and what kind of people do not?

-

3.

Is the shape of the relationship between healthy eating and happiness linear? The healthier one’s diet, the happier one is? Or is there an optimum?

Approach

I explored answers to these three questions in the available research literature and took stock of the findings obtained in quantitative studies on the relation between healthy eating and happiness. I applied a new technique for research reviewing, that takes advantage of an on-line findings archive, the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven 2018a), which allows us to present a lot of findings in a few easy to oversee tabular schemes.

To my knowledge, the research literature on this subject has not been reviewed as yet. One review has considered the observed effect of eating fruit and vegetables on psychological well-being (Rooney et al. 2013), however, this review does not really deal with happiness, as will be defined in “Happiness” section, but is about mental disorders, such as depression and anxiety.

Structure of the Paper

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. I define the key concepts in “Concepts and Measures” section; healthy eating and happiness and give a short account of happiness research. Next, I describe the new review technique in more detail: how the available research findings were gathered and how these are presented in an easy to overview way (Methods section). Then I discuss what answers the available findings have provided for our research questions (Results section). I found a clear answer to the first research question, but no clear answers to the second and third question. I discuss these findings in “Discussion” section and draw conclusions in “Conclusions” section.

Concepts and Measures

There are different view on what constitutes ‘healthy eating’ and ‘happiness’; for this reason, a delineation of these notions is required.

Healthy Eating

I follow the WHO (2018) characterization of a ‘healthy diet’ as involving’: 1) a varied diet, 2) rich in fruit and vegetables 3) a moderate amount of fats and oil and 4) less salt and sugar than usual these days. The typical Mediterranean diet is considered to fit these demands well. Unhealthy foods are considered to be rich in sugar and fat, such as processed meat, fast foods, sweets, cakes, sodas, deserts, alcohol and other foods high in calories, but low in nutritional content.

Happiness

Throughout history, the word happiness has been used to denote different concepts that are loosely connected. Philosophers typically used the word to denote living a good life and often emphasize moral behaviour. ‘Happiness’ has also been used to denote good living conditions and associated with material affluence and physical safety. Today, many social scientists use the word to denote subjective satisfaction with life, which is also referred to as subjective well-being (SWB).

Definition of Happiness

In that latter line, I defined happiness as the degree to which an individual judge the overall quality of his/her life-as-a-whole favourablyFootnote 1 (Veenhoven 1984) and in a later paper distinguished this definition of happiness from other notions of the good life (Veenhoven 2000). In this paper, I follow this conceptualization as it is also the focus of the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven 2018a) from which the data reported in this paper are drawn.

Components of Happiness

Our overall evaluation of life draws on two sources of information: a) how well one feels most of the time and b) to what extent one perceives one is getting from life what one wants from it. I refer to these sub-assessments as ‘components’ of happiness, called respectively ‘hedonic level of affect’ and ‘contentment’ (Veenhoven 1984). The affective component tends to dominate in the overall evaluation of life (Kainulainen et al. 2018).

The affective component is also known as ‘affect balance’, which is the degree to which positive affective (PA) experiences outweigh negative affective (NA) experiences Positive experience typically signals that we are doing well and encourages functioning in several ways (Fredrickson 2004) and protects health (Veenhoven 2008). As such, this aspect of happiness was particularly interesting for this review of effects of healthy eating.

Difference with Wider Notions of Wellbeing

Happiness in the sense of the ‘subjective enjoyment of one’s life-as-a-whole’, should not be equated with satisfaction with domains of life, such as satisfaction with one’s life-style, one’s diet in particular. Likewise, happiness in the sense of the ‘subjective enjoyment of one’s life’ should not be equated with ‘objective’ notions of what is a good life, which are sometimes denoted using the same term. Though strongly related to happiness, mental health is not the same; one can be pathologically happy or be happy in spite of a mental condition.

Differences in wider notions of well-being are discussed in more detail in Veenhoven (15).

Measurement of Happiness

Since happiness is defined as something that is on our mind, it can be measured using questioning. Various ways of questioning have been used, direct questions as well as indirect questions, open questions and closed questions and one-time retrospective questions and repeated questions on happiness in the moment.

Not all questions used fit the above definition of happiness adequately, e.g. not the question whether one thinks one is happier than most people of one’s age, which is an item in the Subjective Happiness Scale (Lyobomirsky and Lepper 1999). Findings obtained using such invalid measures are not included in the World Database of Happiness and hence were not considered in this research synthesis. Further detail on the validity assessment of questions on happiness is available in the introductory text to the collection Measures of Happiness of the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven 2018b) chapter 4. Some illustrative questions deemed valid for archiving in the WDH are presented below.

-

Question on overall happiness:

-

Taking all together, how happy would you say you are these days?

-

Questions on hedonic level of affect:

-

Would you say that you are usually cheerful or dejected?

-

How is your mood today? (Repeated several days).

-

Question on contentment:

-

1)

How important are each of these goals for you?

-

2)

How successful have you been in the pursuit of these goals?

Happiness Research

Over the ages, happiness has been a subject of philosophical speculation and in the second half of the twentieth century it also became the subject of empirical research. In the 1960’s, happiness appeared as a side-subject in research on successful aging (Neugarten et al. 1961) and mental health (Gurin et al. 1960). In the 1970’s happiness became a topic in social indicators research (Veenhoven 2017) and in the 1980s in medical quality of life research (e.g. Calman 1984). Since the 2000’s, happiness has become a main subject in the fields of ‘Positive psychology’ (Lyubomirsky et al. 2005) and ‘Happiness Economics’ (Bruni and Porta 2005). All this has resulted in a spectacular rise in the number of scholarly publications on happiness and in the past year (2017) some 500 new research reports have been published. To date (May 2018), the Bibliography of Happiness list 6451 reports of empirical studies in which a valid measure of happiness has been used (Veenhoven 2018c).

Findings Archive: The World Database of Happiness

This flow of research findings on happiness has grown too big to oversee, even for specialists. For this reason, a findings archive has been established, in which quantitative outcomes are presented in a uniform format and are sorted by subject. This ‘World Database of Happiness’ is freely available on the internet at https://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl

Its structure is shown on Fig. 1 and a recent description of this novel technique for the accumulation of research findings can be found with Veenhoven (2019).

One of the subject categories in the collection of correlational findings is ‘Happiness and Nutrition’ (Veenhoven 2018c). I draw on that source for this paper.

Methods

A first step in this review was to gather the available quantitative research findings on the relationship between happiness and healthy eating. The second step was to present these findings in an uncomplicated form.

Gathering of Research Findings

In order to identify relevant papers for this synthesis, I inspected which publications on the subject of healthy eating were already included of the Bibliography of World Database of Happiness, in the subject sections ‘Health behaviour’ and consumption of ‘Food’. Then to further complete the collection of studies, various databases were searched such as Google Scholar, EBSCO, ScienceDirect, PsycINFO, PubMed/Medline, using terms such as ‘happiness’, ‘life satisfaction’, ‘subjective well-being’, ‘well-being’, ‘daily affect’, ‘positive affect’, ‘negative affect’ in connection with terms such as ‘food’, ‘healthy food’, ‘fruit and vegetables’, ‘fast food ‘and ‘soft drinks’ in different sequences.

All reviewed studies had to meet the following criteria:

-

1.

A report on the study should be available in English, French, German or Spanish.

-

2.

The study should concern happiness in the sense of life-satisfaction (cf. Healthy Eating section). I excluded studies on related matters, such as on mental health or wider notions of ‘flourishing’.

-

3.

The study should involve a valid measure of happiness (cf. Happiness section). I excluded scales that involved questions on different matters, such as the much-used Satisfaction With Life Scale (Diener et al. 1985).

-

4.

The study results had to be expressed using some type of quantitative analysis.

Studies Found

Together, I found 20 reports of an empirical investigation that had examined the relationship between healthy eating and happiness, of which two were working papers and one dissertation. None of these publications reported more than one study. Together, the studies yielded 47 findings.

All the papers were fairly recent, having been published between 2005 and 2017. Most of the papers (44.4%) were published in Medical Journals, including the International Journal of Behavioural Medicine, Journal of Health Psychology, The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, The Journal of Psychosomatic Research, The International Journal of Public Health, and Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology.

People Investigated

Together, the studies covered 149.880 respondents and 27 different countries. The publics investigated in these studies, included the general population in countries and particular groups such as students, children, veterans and medical patients. The majority of respondents belonged to a general public group (50%), students made up 27.8%, with children and veterans each forming 11.1%.

Research Methods Used

Most of the studies were cross-sectional 64.4%, longitudinal and daily food diaries accounted for 22% and 10.2% of the total number of studies respectively, and one experimental study accounted for 3.4%.

I present an overview of all the included studies, including information about population, methods and publication in Table 1.

Format of this Research Synthesis

As announced, I applied a new technique of research reviewing, taking advantage of two technical innovations: a) The availability of an on-line findings-archive (the World Database of Happiness) that holds descriptions of research findings in a standard format and terminology, presented on separate finding pages with a unique internet address. b) The change in academic publishing from print on paper to electronic text read on screen, in which links to that online information can be inserted.

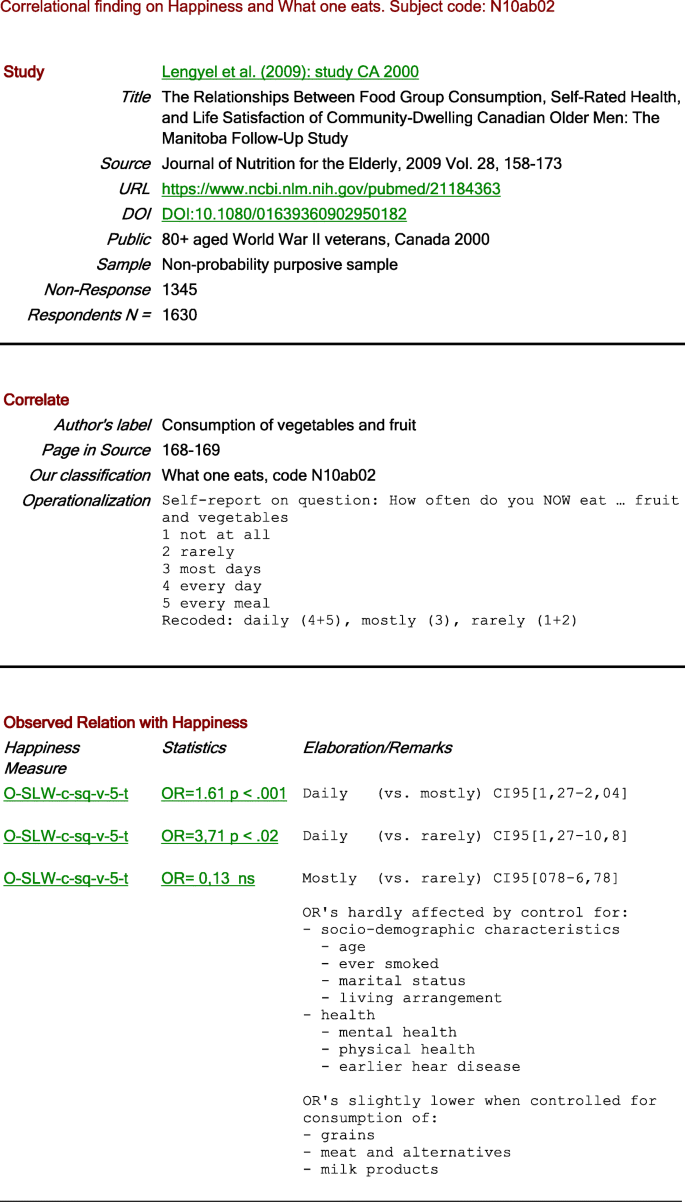

Links to Online Detail

In this review, I summarize the observed statistical relationships as +, − or 0 signs.Footnote 2 These signs link to finding pages in the World Database of Happiness, which serves as an online appendix in this article. If you click on a sign, one such a finding page will open, on which you can see full details of the observed relationship; of the people investigated, sampling, the measurement of both variables and the statistical analysis. An example of such an electronic finding page is presented in Fig. 2. This technique allows me to present the main trends in the findings, without burdening the reader with all the details, while keeping the paper to a controllable size, at the same time allowing the reader to check in depth any detail they wish.

Organization of the Findings

I first sorted the findings by the research method used and these are presented in three separate tables. I distinguished a) cross-sectional studies, assessing same-time relationships between diet and happiness (Table 2), b) longitudinal studies, assessing change in happiness following changes in diet (Table 3), and c) experimental studies, assessing the effect of induced changes in diet on happiness (Table 4).

In the tables, I distinguish between studies at the micro level, in which the relation between diet and happiness of individuals was assessed and studies at the macro level, in which average diet in nations is linked to average happiness of citizens.

I present kinds of foods consumed vertically and horizontally two kinds of happiness: overall happiness (life-satisfaction) and hedonic level of affect.

Presentation of the Findings

The observed quantitative relationships between diet and happiness are summarized using 3 possible signs: + for a positive relationship, − for a negative relationship and 0 for a non-relationship. Statistical significance is indicated by printing the sign in bold. See Appendix. Each sign contains a link to a particular finding page in the World Database of Happiness, where you can find more detail on the checked finding.

Some of these findings appear in more than one cell of the tables. This is the case for pages on which a ‘raw’ (zero-order) correlation is reported next to a ‘partial’ correlation in which the effect of the control variables is removed. Likewise, you will find links to the same findings page at the micro level and the macro level in Table 2; on this page there is a time-graph of sequential studies in Russia from which both micro and macro findings can be read.

Several cells in the tables remain empty and denote blanks in our knowledge.

Advantages and Disadvantages of this Review Technique

There are pros and cons to the use of a findings-archive such as the World Database of Happiness and plusses and minuses to the use of links to an on-line source in a text like this one.

Use of a Findings-Archive

Advantages are: a) efficient gathering of research on a particular topic, happiness in this case, b) sharp conceptual focus and selection of studies on that basis, c) uniform description of research findings on electronic finding pages, using a standard format and a technical terminology, d) storage of these finding pages in a well searchable database, e) which is available on-line and f) to which links can be made from texts. The technique is particular useful for ongoing harvesting of research findings on a particular subject.

Disadvantages are: a) the sharp conceptual focus cannot easily be changed, b) considerable investment is required to develop explicit criteria for inclusion, definition of technical terms and software,Footnote 3 c) which pays only when a lot of research is processed on a continuous basis.

Use of Links in a Review Paper

The use of links to an on-line source allows us to provide extremely short summaries of research findings, in this text by using +, − and 0 signs in bold or not, while allowing the reader access to the full details of the research. This technique was used in an earlier research synthesis on wealth and happiness (Jantsch and Veenhoven 2019) and is described in more detail in Veenhoven (2019). Advantages of such representation are: a) an easy overview of the main trend in the findings, in this case many + signs for healthy foods, b) access to the full details behind the links, c) an easy overview of the white spots in the empty cells in the tables, and d) easy updates, by entering new sign in the tables, possibly marked with a colour.

The disadvantages are: a) much of the detailed information is not directly visible in the + and – signs, b) in particular not the effect size and control variables used, and c) the links work only for electronic texts.

Differences with Traditional Reviewing

Usual review articles cannot report much detail about the studies considered and rely heavily on references to the research reports read by the reviewer, which typically figure on a long list at the end of the review paper that the reader can hardly check. As a result, such reviews are vulnerable to interpretations made by the reviewer and methodological variation can escape the eye.

Another difference is that the conceptual focus of many traditional reviews in this field is often loose, covering fuzzy notions of ‘well-being’ rather than a well-defined concept of ‘happiness’ as used here. This blurs the view on what the data tell and involves a risk of ‘cherry picking’ by reviewers. A related difference is that traditional reviews of happiness research often assume that the name of a questionnaire corresponds with its conceptual contents. Yet, several ‘happiness scales’ measure different things than happiness as defined in “Healthy Eating” section, e.g. much used Life Satisfaction Scale (Neugarten et al. 1961), which measures social functioning.

Still another difference is that traditional narrative reviews focus on interpretations advanced by authors of research reports, while in this quantitative research synthesis I focus on the data actually presented. An example of such a difference in this review, is the publication by Connor & Brookie (Conner et al. 2015) who report no effect of healthier eating on mood in the experimental group, while their data show a small but significant gain in positive affect and a small but insignificant reduction of negative effect (Table 3), which together denote a positive effect on affect balance.

Difference with Traditional Meta-Analysis

Though this research synthesis is a kind of meta-analysis, it differs from common meta-analytic studies in several ways. One difference is the above- mentioned conceptual rigor; like narrative reviews many meta-analyses take the names given to variables for their content thus adding apples and oranges. Another difference is the direct online access to full detail about the research findings considered, presented in a standard format and terminology, while traditional meta-analytic studies just provide a reference to research reports from which the data were taken. A last difference is that most traditional meta-analytic studies aim at summarizing the research findings in numbers, such as an average effect size. Such quantification is not well possible for the data at hand here and not required for answering our research questions. My presentation of the separate findings in tabular schemers provides more information, both of the general tendency and of the details.

Results

Let us now revert to the research questions (Structure of the Paper section) and answer these one by one.

Is there a Trade-Of between Healthy Eating and Happiness?

Or Does Healthy Eating Rather Add to Happiness or Do the Positive and Negative Effects Balance?

This question was addressed using different methods, a) same-time comparison of diet and happiness (cross-sectional analysis) b) follow-up of change in happiness following change in diet (longitudinal) and c) assessing the effect on happiness of induced change in diet (experimental). The results are summarized in, respectively, Tables 2, 3 and 4.

Cross-Sectional Findings

Together I found 42 correlational findings, which are presented in Table 2. Of these findings 14 concerned raw correlations, while 28 reflected the results of a multivariate analysis. In Table 2 I see only micro level studies.

Main Trend

There were 16 + signs, which indicates that people who eat healthy tend to be happier than people who do not. A few (3) – signs were linked to unhealthy eating habits, i.e. fast food, soft drinks and sweets, and as such support this pattern.

Exceptions

Not all the findings supported the view that healthy eating goes with greater happiness. Consumption of soft-drinks was positively related to overall happiness, though not significantly, while the correlation with affect balance was significantly negative. A high intake of high caloric protein and fat is generally deemed to be unhealthy but appeared in one case to go with greater overall happiness, a study among medical patients in Arkhangelsk in Russia, where the medical conditions and cold climate may have require a higher intake of such foods.

Undecided

The findings were mixed with respect to the relation of happiness with consumption of animal products, dairy and meat. For these foods a positive relation with overall happiness was found and a negative relation with affect level, in the case of milk products both relations were insignificant.

Controls

Several studies report both raw correlations and partial ones for the same population. Controls reduced the effect size somewhat but did not change the direction of the correlation. Importantly, the control for health and other health behaviours in 8 studiesFootnote 4 did not change the direction of the correlation.

Longitudinal Findings

The findings of two studies that assessed the change in happiness following change in diet are presented in Table 3, one study at the micro level among students and another study at the macro-level among the general population in Russia. Both studies found positive correlations, indicating that healthier eating adds to one’s happiness. The effects of greater consumption of meat and milk were not significant. No control variables were used in these studies. The relationship between healthy eating and affect level was not investigated longitudinally.

Experimental Study

To date, there is only one study on the effect of induced change to a healthier diet on an individual’s happiness. In this study people were randomly assigned to an experimental group and stimulated in various ways to consume more fruit and vegetables (FV), among other things by providing vouchers for health foods and sending e-mail reminders. After 2 weeks of increased FV consumption, the participant’s mood level had increased more than those of the control group.

In Sum

Together, these findings provide a clear answer to our first research question. The net effect of healthy eating on happiness tends to be positive. If there is any trade-off at all, this is apparently more than compensated by the trade-on. The positive relationship is robust across research methods and measures of happiness.

Is this Effect of Healthy Eating on Happiness Similar for Everybody?

If Not, What Kind of People Profit from Healthy Eating and What Kind of People Do Not?

The 19 studies reported here cover a wide range of populations, the general public in several parts of the world, children, students, church members, medical patients and elderly war veterans. No great differences in the correlation between diet and happiness appear in these findings, though children seem to be happier when allowed to consume sweets and soft drinks. The cross-national study by Grant et al. (2009) observed some differences in strength of the correlation between healthy eating and happiness across part of the world, but no difference in direction of the correlation. The micro-level studies by Pettay (2008) and Warner et al. (2017) found no differences between males and females, while Ford et al. (2013) found a slightly bigger negative effect of unhealthy eating among women than among men.

In Sum

The observed positive effect of healthy eating on happiness seems to be universal. Possible differences in what diet provides the most happiness for whom have not (yet) been identified.

Is the Shape of The Relationship Linear; the Healthier One’s Diet, the Happier One Is?

Or Is there an Optimum, if So What Is Optimal for Whom?

Two studies find a linear relation between happiness and the number of portions fruits and vegetables per day, Lesani et al. (2016) among students in Iran and Blanchflower et al. (2013) among the general public in the UK, the latter study up to 7–8 portion a day. Another study observed an optimum at the lower level of 3–4 portions a day among female Iranian students (Fararouei et al. 2013). These thee studies suggest that the optimum is at least beyond three portions a day. As yet the focus of research has been on particular kinds of food, while the relationship between happiness and total diet composition has not been investigated.

Discussion

Together, our findings leave no doubt that healthy eating ads to happiness, frequent consumption of fruit and vegetables in particular.

Causal Effect

Though happiness may influence nutrition behaviour, happier people being more inclined to follow a healthy diet, there is strong evidence for a causal effect of healthy eating on happiness. Spurious correlation is unlikely to exist, since correlations remain positive after controlling for many different variables. Causality is strongly suggested by 3 out of the 4 longitudinal findings and the experimental study.

This is not to say that healthy eating will always add to the happiness of everybody, but the trend is sufficiently universal and strong to be used in policies that aim at greater happiness for a greater number of people, such as in happiness education.

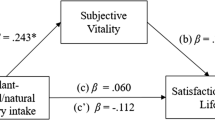

Causal Paths

Healthy eating will add to good health and good health will add to happiness. An unexpected finding is that the effect of healthy eating on happiness is not fully mediated by better health. As mentioned in “Is there a Trade-Of between Healthy Eating and Happiness?” section, significant positive correlations remain when health is controlled. This means that healthy eating also affects happiness in other ways. As yet I can only speculate about what these ways are. Possibly effects are that healthy eaters attract nicer people or that intake of fruit and vegetables has a direct effect on mood.

Limitations

This first synthesis of the research on happiness and healthy eating draws on 20 empirical studies, which together yielded 47 findings. Though these results provide strong indications of a positive effect of healthy eating on happiness, we need more research to be sure. This research synthesis limits to happiness defined as the subjective enjoyment of one’s life as a whole and measure that matter adequately. This conceptual focus has a piece, we came to know more about less. The available research findings do not allow a traditional meta-analysis, both because of the limited numbers and their heterogeneity. Hence, we cannot yet compute effect sizes or test statistical significance of differences.

Topics for Further Research

Although we now know that healthy eating tends to make one’s life more satisfying, we do not know in much detail what particular diets are the most conducive to the happiness of what kinds of people. We are also largely in the dark about the causal mechanisms involved. The focus of current research is very much on particular food items, consumption of fruit and vegetables in particular. Future research should pay more attention to the effect of total diets on happiness.

Conclusions

Healthy eating adds to happiness, not just by protecting one’s health but also in other, as yet unidentified, ways. This finding deserves to be drawn to the public’s attention. People should know that changing to a healthier diet will not be at the cost of their happiness but will add to it. Faulty beliefs and misleading advertisements should be counter-balanced by this established fact.

Notes

Likewise, Diener (26) defined ‘life satisfaction’ as an overall judgement of one’s life.

The technique also allows summarization in a number, which can be presented in a stem-leaf diagram, or in short verbal. Statements, such as ‘U shaped relationship’

The archive can be easily adjusted for other subjects. The software is Open Source

References

Studies Included in this Research Synthesis Are Marked with a Link below the Reference. The Links Lead to a Standardized Description of that Study in the World Database of Happiness. The Codes Denote Place and Year of the Study

Averina, M. M., Brox, J. & Nilsson, O. (2005) Social and lifestyle determinants of depression, anxiety, sleeping disorders and self-evaluated quality of life in Russia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 40: 511–518 Study RU Archangelsk 1999

Baum-Baicker, C. (1985). The psychological benefits of moderate alcohol consumption: a review of the literature. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 15(4), 305–322.

Bazzano, L. A., He, J., Ogden, L. G., Loria, C. M., Vupputuri, S., Myers, L., & Whelton, P. K. (2002). Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of cardiovascular disease in US adults: the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Epidemiologic Follow-up. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 76(1), 93–99.

Becker, E. S., Margraf, J., Türke, C., Soeder, U., & Neumer, S. (2001). Obesity and mental illness in a representative sample of young women. International Journal of Obesity Related Metabolic Disorders, 25(Suppl. 1), S5–S9.

Blanchflower, D. G., Oswald, A. J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2013). Is psychological well-being linked to the consumption of fruit and vegetables? Social Indicators Research, 114, 785–801 Study GB Wales 2007-2010.

Breslin, G., Donnelly, P., & Nevill, A. M. (2013). Socio-demographic and behavioural differences and associations with happiness for those who are in good and poor health. International Journal of Happiness and Development, 1, 142–154 Study GB 2009.

Bruni, L., & Porta, P. L. (2005). Economics and happines. UK: Oxford University Press.

Caligiuri, S., Lengyel, C. O., & Tate, R. B. (2012). Changes in food group consumption and associations with self-rated diet, health, life satisfaction, and mental and physical functioning over 5 years in very old Canadian men: The Manitoba follow-up study. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 16(8), 707–712 Study CA 2000-2005.

Calman, A. C. (1984). Quality of life in cancer patients--a hypothesis. Journal of Medical Ethics, 10, 124–127.

Chang, H. H., & Nayga, R. M., Jr. (2010). Childhood obesity and unhappiness: The influence of soft drinks and fast food consumption. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11, 261–275 Study TW 2001.

Conner, T.S. & Brookie, K.L. (2017). Let them eat fruit! The effect of fruit and vegetable consumption on the psychological well-being in young adults: A randomized controlled trial. PLOS one, February. 3201 Study NZ Auckland 2015

Conner, T.S., Brookie, K.L. & Richardson, A.C. (2015). On carrots and curiosity: Eating fruit and vegetables is associated with greater flourishing in daily life. British Journal of Health Psychology, 20: 413–444. Study NZ Auckland 2013

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Griffin, S., & Larsen, R. J. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Fararouei, M., Akbartabar Toori, M. & Brown, I.J. (2013). Happiness and health behaviour in Iranian adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescence, 36: 1187–1192. Study IR 2008

Ford, P.A., Jaceldo-Siegl, K. & Lee, J.W. (2013). Intake of mediterranean foods associated with positive and low negative affect. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 74 (2013) 142–148. Study ZZ Anglo-America 2002

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden - and - build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions, Biological Sciences, 359: 1367–1377.

Grant, N.; Steptoe, A.; Wardle, J. (2009). The relationship between life satisfaction and health behaviour: a cross-cultural analysis of young adults. International Journal of Behavioural Medicine, 16: 259–268 Study ZZ 1999-2001

Gschwandtner, A., Jewell, S. & Kambhampati, U. (2015). On the relationship between lifestyle and happiness in the UK. Paper for 89th Annual Conference of AES, 2015, 1–33, Warwick, England. Study GB 2012

Gurin, G., Feld, S. & Veroff, J. (1960). Americans view their mental health. A nationwide interview survey. Basic Books, New York, USA (Reprint in 1980, Arno Press, New York, USA).

Honkala, S., Al Sahli, N., & Honkala, E. (2006). Consumption of sugar products and associated life- and school- satisfaction and self-esteem factors among schoolchildren in Kuwait. Acta Odonatological Scandinavia, 64, 79–88 Study KW 2002.

Huffman, S.K.; Rizov, M. (2016). Life satisfaction and diet: Evidence from the Russian longitudinal monitoring survey. Paper prepared for presentation at the Agricultural & Applied Economics Association Annual Meeting, 2016, 1–25, Boston, Massachusetts. Study RU 1994-2005

Jantsch, A & Veenhoven, R. (2019). Private wealth and happiness: A research synthesis using an online findings archive. In Gael Brule & Christian Suter (Eds.), “Wealth(s) and Subjective Well-Being Springer/Nature, pp 17–50.

Kainulainen, S., Saari, J., & Veenhoven, R. (2018). Life-satisfaction is more a matter of how well you feel, than of having what you want. International Journal of Happiness and Development, 4(3), 209–235.

Kye, S.K. & Park, K. (2014). Health-related determinants of Happiness in Korean Adults. International Journal of Public Health, 59: 731–738. Study KR 2009

Lengyel, C. O., Oberik Blatz, A. K., & Tate, R. B. (2009). The relationships between food group consumption, self-rated health, and life satisfaction of community-dwelling canadian older men: The manitoba follow-up study. Journal of Nutrition for the Elderly, 28, 158–173 Study CA 2000.

Lesani, A., Javadi, M., & Mohammadpoorasl, A. (2016). Eating breakfast, fruit and vegetable intake and their relation with happiness in college students. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 21, 645–651 Study IR Tehran 2011.

Liu, S., Manson, J. E., Lee, I. M., Cole, S. R., Hennekens, C. H., Willett, W. C., & Buring, J. E. (2000). Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: The Women’s Health Study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 72(4), 922–928.

Lyobomirsky, S., & Lepper, H. S. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research, 46, 137–155.

Lyubomirsky, S., Diener, E., & King, L. A. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131, 803–855.

Mujcic, R., & Oswald, A. (2016). Evolution of well-being and happiness after increases in consumption of fruit and vegetables. American Journal of Public Health, 106(8), 1504–1510 Study AU 2007-2009.

Neugarten, B.L., Havighurst, R.J. & Tobin, S. S. (1961). The measurement of life satisfaction. Journal of Gerontology, 16: 134–143.

Oyebode, O., Gordon-Dseagu, V., Walker, A., & Mindell, J. S. (2014). Fruit and vegetable consumption and all-cause, cancer and CVD mortality: analysis of Health Survey for England data. Journal of Epidemiological Community Health, 68(9), 856–862.

Pettay, R.S. (2008). Health behaviours and life satisfaction in college students. PhD Thesis, Kansas State University, USA. Study US 2006

Rooney, C., McKinley, M.C. & Woodside, J.V. (2013). The Potential Role of Fruit and Vegetables in aspects of Psychological Well-Being: A Review of the Literature and Future Directions. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 72: 420–432.

Stough, C., Scholey, A., Lloyd, J., Spong, J., Myers, S., & Downey, L. A. (2011). The effect of 90-day administration of a high dose vitamin B-complex on work stress. Human Physio-pharmacology, 26(7), 470–476.

Veenhoven, R. (1984). Conditions of happiness. Reidel (now Springer), Dordrecht, Netherlands.

Veenhoven, R. (2000). The four qualities of life. Ordering concepts and measures of the good life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1, 1–39.

Veenhoven, R. (2008). Healthy happiness: Effects of happiness on physical health and the consequences for preventive health care. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 449–464.

Veenhoven, R. (2017). Co-development of happiness research: Addition to “fifty years after the social indicator movement. Social Indicators Research, 135: 1001–1007.

Veenhoven, R. (2018a) World database of happiness: Archive of research findings on subjective enjoyment of life. Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Veenhoven, R. (2018b). Measures of happiness. World Database of Happiness, Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Veenhoven, R. (2018c). Bibliography of happiness. World Database of Happiness, Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Veenhoven, R. (2019). World database of happiness: A ‘findings archive’. Chapter in Handbook of Wellbeing, Happiness and the Environment. Editors: Heinz Welsch, David Maddison and Katrin Rehdanz, Edward Elgar Publishing (forthcoming).

Warner, R.M., Frye, K. & Morrell, J. S. (2017). Fruit and vegetable intake predicts positive affect. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18: 809–826. Study US New England 2013

WHO (2018) Healthy diet. http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Signs used in Finding Tables

- + :

-

positive correlation, statistically significant

- + −:

-

positive correlation, not statistically significant

- +/–:

-

positive and negative correlations, depending on control variables used

- 0:

-

no correlation

- –:

-

negative correlation, not statistically significant

- – :

-

negative correlation, statistically significant

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Veenhoven, R. Will Healthy Eating Make You Happier? A Research Synthesis Using an Online Findings Archive. Applied Research Quality Life 16, 221–240 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09748-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09748-7