Abstract

In early 2019, an archaeological excavation was undertaken at the former docklands area of Leith, Scotland in advance of development works by CALA Homes (East) Ltd. The focus of excavation was an area of the docks that had long been infilled and the investigations sought to reveal surviving evidence of the West Old Docks, constructed in the early nineteenth century and later known as the Queen’s Docks. Well-preserved structural remains and a suite of associated artefacts, including the rare survival of a ship’s rope fender of likely nineteenth century date, have provided a valuable opportunity investigate the development and growth of this area of the docklands over time as well as affording the chance to assess the critical role of John Rennie, a renowned engineer, and one of the architects of Leith’s early harbor design, in the success of Leith’s nineteenth century growth. This study, incorporating archaeological, cartographic, and documentary research, has allowed a new understanding of the development of Leith’s harbor and docks during the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, enabling insights into the expansion and contraction in the fortunes of the port and its burgeoning industries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The port district of Leith has played a prominent role in the development of Scotland’s commercial and urban story since the twelfth century AD and at its height in later medieval and post-medieval times was both the major port serving Scotland’s capital, Edinburgh, and a bustling seat of industry in its own right. The docklands of Leith functioned as a key center for trade and commerce and the port’s strategic position on the Firth of Forth led to its subjection to military incursions. Its significance as Edinburgh’s maritime gateway led in the late eighteenth century to the construction of Leith Fort, a defensive battery that was built to protect the harbor, which remained in active use until 1955. More recently, areas of the docks have been de-industrialized with large swathes of the former harbor being developed into a thriving residential and business quarter (Matthews and Satsangi 2007: p. 501). Many of the historic structural elements of Leith’s maritime past have therefore been swept aside but some are merely hidden under the surface.

In early 2019, an archaeological excavation was undertaken at the site of Leith’s West Old Dock (National Grid Reference: NT 26702 76960), also known as the Queen’s Dock (Figs. 1 and 2) in advance of development work by CALA Homes (East) Ltd. This development provided an opportunity to revisit this significant structure and associated elements of Leith’s historic harbor and docklands, designed and constructed at the start of the nineteenth century by the Scottish engineer John Rennie.

In addition to providing a valuable opportunity to reveal and record any surviving elements of the harbor and the docks, the 2019 excavation aimed to understand to what extent any original dockland structures had been impacted by historic and modern development. In addition, it was used to investigate how the structural development of the docks could provide a way of measuring the social and economic impact of the expansion of Scotland’s maritime trade networks on the town, particularly from the late eighteenth century onwards. This has involved comparing historic cartographic evidence against the structural features identified during the excavation to elucidate identifiable changes associated with the port’s development over time, both as a center of maritime trade but also as a strategic military location. The project also afforded the chance to assess the critical role of John Rennie, a renowned engineer and one of the architects of Leith’s early harbor design, in the success of Leith’s nineteenth century growth, allowing comparison with contemporary evidence of harbor development in other coastal areas of Scotland.

These research aims, developed at the outset of the project, incorporated key themes identified by the Scottish Archaeological Research Framework’s (ScARF) Marine and Maritime panel who highlighted the ‘bountiful archaeological research’ potential of Scotland’s harbors and ports (ScARF 2012: p. 31). In this framework, emphasis was placed on the importance of developing research which could lead to a better understanding of the evolution of Scotland’s harbors and in particular, the role that the development of major ports, such as those at Glasgow and Leith, played in the success and expansion of the surrounding towns and cities as well as the industries that powered maritime trade networks (ScARF 2012: p. 30).

This study, incorporating archaeological, cartographic, and documentary research, has allowed a new understanding of the development of the harbor and docks in this area of Leith during the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, enabling insights into the expansion and contraction in the fortunes of the port and its burgeoning industries.

Historic Background to Leith and its Docks

Leith originated as a small fishing village, located at the mouth of the Water of Leith, 3 km (km) north of the medieval center of Edinburgh (Fig. 3) in southeast Scotland. The first historic record of Leith is in King David I’s Holyrood Charter, granting ‘Inverlieth’ or ‘the mouth of Leith’ to the Abbey of Holyrood in 1128 (Mowat 1999: p. 1). At this point Leith is referred to as two areas separated by the Water of Leith, consisting of the Abbey lands to the north and a harbor to the south (Stronach 2002: p. 386). Previous archaeological excavations at Ronaldson’s Wharf in north Leith have revealed activity from the eleventh century AD in the form of occupation deposits suggestive of a fishing village involved in seasonal trade (Reed and Lawson 1999; Stronach 2002: p. 386). Later development saw timber structures erected along the street frontage, associated with bread ovens, hearths, fish and net drying racks, rubbish pits, spreads of midden and a well. In addition, cultivation plots were identified to the rear of these structures. The timber buildings were replaced with structures with clay-bonded stone foundations supporting timber superstructures towards the end of the thirteenth century (Reed and Lawson 1999). The construction of a substantial sea wall demarcated the northern extent of settlement during the fourteenth century and by the fifteenth century small industrial workshops were established within each plot, including a possible smithy, processing pits and a potter’s workshop (Lawson 1999: p. 40).

On the opposing south shore, the location of the early Abbey harbor has been identified through its association with a row of properties located between Tolbooth Wynd and St Andrews Street (Mowat 1999; Stronach 2002: p. 386). Towards the river mouth, excavation of the King’s Harbor revealed accumulations of midden deposits which have been dated through associated pottery to the twelfth century and later (Lawson 1995). Contemporary with this are the foundations for medieval buildings on the frontage at what is now Shore Place while areas around Water Street may have been used for open-air fish processing on an occasional basis (Stronach 2002: p. 386). At Bernard Street, evidence for large-scale land reclamation during the fifteenth century is indicated by the deposition of significant quantities of soil and sand mixed with domestic refuse, found during previous excavations in layers up to 1 m in depth, over the natural beach and foreshore. Also uncovered was an early wall used to hold back the sand dunes (Holmes 1985: pp. 403–404). In 1493 Abbot Robert Bellenden constructed a bridge at the site of St Ninian’s Chapel on the Water of Leith, which until that point had to be crossed by ford or ferry (Mowat 1994: p. 35). This bridge formed a crucial link between the north and south shores, catalyzing the development of north Leith, which could provide accommodation for mariners and storage for cargo (Gifford et al 1984: p. 449; Hickman 2009: p. 119).

Commerce through Leith’s port is thought to have increased from the thirteenth century, consolidated by the effective elimination of Leith’s main nearby rival as a port, Berwick-Upon-Tweed, during the second Wars of Independence in the early fourteenth century (Stronach 2002: p. 386). Not only did the volume of goods arriving at Leith’s port increase but the variety of goods traded also expanded as a result of new networks of exchange, which created the opportunity to redistribute a wealth of Scotland’s own produce (ibid: 387; Mowat 1994). A significant proportion of these exports comprised wools, skins, and textiles (McNeill and MacQueen 1996: pp. 238–242), whilst timber and luxury goods, particularly wine, were imported from the continent (Stronach 2002: p. 387). Towards the end of the later medieval period Leith is thought to have been the busiest port in Scotland, the town flourishing as a result of the various industries that sprang up in response to this increase in trade.

The expansion of the town of Leith around the harbor attests to the growth of medieval and early post-medieval fishing, increasing trade links and the burgeoning population drawn to the town due to the possibilities for employment spurred on by Leith’s growing economic success.

This success, however, came at a price, and Leith become the focus of a series of significant military power struggles during the sixteenth century. Particular episodes of destruction occurred in 1544 and 1547 at the hands of King Henry VIII’s army, which led to the construction of fortifications in 1548, ordered by Mary of Guise (Mowat 1994: pp. 114–115). These works were undertaken by French troops, enclosing what is today Bernard Street, Constitution Street, Great Junction Street, and a segment of the west bank around Sandport Street. The fortifications included a bastion wall known as Ramsey’s Fort, located close to a wooden pier and a small basin for fixing and launching ships at Sandport Street (Mowat 1994: pp. 114–115; Gifford et al. 1984: p. 460). In 1560, the Siege of Leith resulted in the destruction of the port’s defensive walls. A surviving section of the fort’s north-east bastion has been uncovered during excavations between Tower Street and Timber Bush (Cook 2001: p. 44; Moore and Wilson 2001), while elements of the ditches associated with the fort’s defensive system were also uncovered during archaeological investigations ahead of a tram network though Edinburgh’s city center (Spanou 2009: p. 7).

Despite the disruption to trade that inevitably ensued as the result of these military incursions, Leith continued to evolve as a commercial port. Throughout the sixteenth century trade continued to expand between Scotland and the continent, including a steady increase in coal exported to places such as Scandinavia (Hickman 2009: p. 120). Coal was also brought through the port from local areas to support the various industries established in the town, including metalworking, brewing, soapmaking, sugar boiling, and whale oil extraction (Mowat 2003: p. 342).

Leith had clearly established itself as a major port by the end of the seventeenth century (Hickman 2009: p. 121), even after the devastation brought by a visitation of the plague in 1645, when an estimated two thirds of its population is thought to have succumbed (Mowat 1994: p. 185). As Leith’s important role as a trading center and shipbuilding town increased around the year 1700, the demand for shipping services increased, together with the need for expansion of the dock area to accommodate the growth in the volume of vessels visiting the port and their increased cargo loads. The Town Council applied to the Government of Queen Anne, requesting permission to carry out development of ‘a wet and dry dock’ through ‘improvements’ which would enable construction, fitting and careening to be carried out (Marshall 1986: p. 28). In 1720 Scotland’s first ever dry dock may have been constructed between Sandport Street and the river, followed by the construction of a second dry dock further upriver in North Leith (Marshall 1986: pp. 24–28). A contemporary account by Maitland which describes the ‘improvements’ makes no mention, however, of any dry docks, with later sources offering a date in the latter half of the eighteenth century for the construction of John Sime’s dry dock at Sandport (Mowat 2003: p. 239). In 1777, a short pier known as the Custom House Quay was built to further expand and regulate Leith’s shipping capabilities including the processing of cargo.

The location and tidal conditions of the port at Leith have been described as less favorable due to its position on a sandy foreshore rather than on a natural harbor (Groome 1885; White 1900: p. 293). Additionally, the persistent dumping of alluvial silts deriving from the Water of Leith resulted in the growth of the natural sandbar at the harbor’s mouth (Walker and Cubitt 1839: p. 20), sometimes preventing the entry of vessels into the harbor unless at the high-water mark. As the success and scale of Leith’s trading and industrial enterprises grew, the existing post-medieval harbor’s various inadequacies were seen to limit progress. Overcrowding, the inability to accommodate larger ships, and frequent delays in loading and unloading cargo, all came at great monetary expense and risked economic capital, eventually forcing parliament to intervene (Marshall 1986: p. 28). Plans were made in 1754 for a new basin in north Leith which would contain ‘docks, wharves, quays and other proper conveniences…for building, repairing, loading, unloading, wintering, and laying up of ships and vessels’ (Mowat 2003: p. 236). It would, however, take a second act of Parliament in 1787, backed by the Town Council, for the development work to begin (ibid: 236).

Establishment of the Docks

The layout of the current docks at Leith represents centuries of industrial development, involving land reclamation, construction, and expansion, necessitated by increasing trade, in particular from the eighteenth century onwards, which required the construction of ever larger and more effective harbor infrastructure.

The boom in industry during the late eighteenth and nineteenth century was in part led by the advancements in, and the harnessing of, steam-powered machinery (fuelled by coal and later, coke), spurring episodes of economic growth and instigating new opportunities for trade and exchange. This increased the demand on maritime services to facilitate the exportation and importation of commodities and put pressure on Scotland’s existing harbors and ports, which struggled to cope with the increase in vessel numbers and size. As exemplified at Leith, harbor and port development was required across Scotland on an unprecedented scale in reaction to this, leading to expansions in the size and complexity of major commercial docks and harbors such as those at Glasgow and Aberdeen, as well as demanding overhauls of some of Scotland’s vernacular harbors (ScARF 2012: p. 30).

The four largest ports during the mid to late eighteenth century in terms of weight of goods traded and income were Greenock, Port Glasgow, Leith, and Aberdeen, in that order (Rossner 2011). At this time, there was a significant division in the trade links accessed by the east and west coast ports, due to their facing different trade routes, with Glasgow and Greenock being involved in the triangular trade of commodities to and from North America, the Caribbean and Africa, including tobacco, cotton, sugar, coffee and, regrettably, slaves, while east coast ports such as Leith and Aberdeen were geared towards the importation of timber, flax and wine from Europe and the Baltic to be sold to the burgeoning upper classes (Rossner 2011: 15). By the mid-nineteenth century, trade with Asia also played a significant role in Scotland’s maritime economy, not least of which was Dundee’s important trade links with India for the importation of jute and other commodities. These major Scottish ports were developed during this period with the benefit of state funding and under the direction of renowned Scottish civil engineers such as Thomas Telford and John Rennie (ScARF 2012: p. 30).

Following the second act of parliament in 1787 which sought to address the inadequacies of the then current port facilities at Leith, John Rennie was employed in 1799 to assess the port area and augment the design of the docks to facilitate the growth of trade (Mowat 2003: p. 298; Rennie 1847a). Rennie is renowned for his prolific career as both a civil and mechanical engineer and can be considered as one of the instigators of the boom in large civil engineering projects across the country at the time. Often working in competition with Thomas Telford, Rennie was a prolific advocate of advancing improvements to rivers, drainage schemes, harbors, and docks, including constructing ambitious designs for canals, reservoirs, bridges, and lighthouses (Mowat 2003: p. 136). Rennie’s contribution to the improvement of Scotland’s infrastructure includes a comprehensive list of engineering achievements including the development of harbors at Helmsdale, Fraserburgh, Queensferry, Greenock, and Leith, as well as his role in the development of the Edinburgh to Glasgow Union Canal (Cross-Rudkin 2011: p. 188). South of the border he was equally prolific, working on major redevelopments of harbors and ports in Berwick, Liverpool, London, and the naval dockyards at Plymouth, to name a few. He is also credited with making a major contribution to the wide-scale adoption of steam-powered machinery within large civil engineering projects such as during his work on the establishment of the East and West India Docks on the Thames (ibid: 189).

Rennie’s initial involvement at Leith included providing designs for two new wet dock basins and a number of dry docks or ‘graving’ docks on the west side of the river (Rennie 1847a). These two new wet docks were known as the East Wet Dock and the West Wet Dock. Rennie’s intention was to build a third and much larger dock at the deep-water entrance of Newhaven, but the latter never came to fruition due to a lack of funds. The value of the proposed improvements totalled £302,290, representing a massive expenditure and investment (Marshall 1986: p. 28). These docks were the first of their kind in northern Britain; they were designed to allow ships to enter the dock via a lock system that ensured a constant water level that permitted vessels to remain afloat during any tide (ibid: 28).

The first foundation stone for the East Wet Dock was reportedly laid in May 1801 and it opened in 1806. The occasion was marked with the sound of artillery fire from His Majesty George III’s war ships anchored just off the coast, and from Leith Fort which had itself only recently been built (c.1780) to protect the relatively vulnerable seaport (Mowat 2003: p. 298). Construction of the West Wet Dock commenced in 1810, with its completion occurring in 1817. The two docks were connected by a passageway and separated by an iron swing bridge, which was hand-operated by a series of winches and capstans (ibid: 298). Rennie’s western basin within the West Wet Dock, also later known as the Queen’s Dock, is first depicted on John Ainslie’s map of Edinburgh and Leith in 1804 as one of a series of WNW/ESE-aligned basins following the approximate alignment of the coast (Fig. 4). The dock is shown to be enclosed by an outer wall stretching out to the west towards Newhaven; it is also mentioned in an old account as having a ‘strong retaining wall, in the building of which not less than 250,000 cubic feet of ashlar was employed, [which] protects them from the sea’ (Groome 1885: p. 484). Also evident on Ainslie’s map are discrete outlines in the form of block-like structures with pitched outward-looking faces, labelled as ‘proposed fortifications’, one located to the immediate north of the West Wet Dock. During the excavation work of 2019, features corresponding to those on Ainslie’s map were recognized amongst the surviving structures. It is possible to follow the development and modifications to these structures on later cartographic plans, which together tell the story of Leith dock’s nineteenth century and later developments.

Detail from John Ainslie’s map showing the proposed docks, 1804 (Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland and under Creative Commons (CC BY 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Excavation of the Sea Wall

The structural features (Fig. 3) that were the focus of the excavation by AOC Archaeology Group in January 2019 (Wallace 2019) were found to be covered by a deep layer of made ground, comprising modern building debris and redeposited clay, including a range of artifactual material deriving from industrial and household waste. Generally, the preserved structural remains survived in good condition under this thick levelling deposit which may represent the final infilling of the area in the early 1970s.

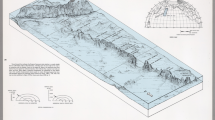

Exposed in the central area of excavation (Fig. 5 and 6) were the remains of a substantial surviving section of a heavily truncated wide linear wall, aligned east to west, with an acutely angled protruding kink in the outer face of the wall towards its surviving northernmost extent, visible towards the center of Fig. 7. This long and substantial wall base was truncated at its eastern extent by a horseshoe-shaped structure representing the surviving remains of the wall of a later dry dock (identified as the East Dry Dock) and was associated with a variety of narrow linear culverts and other stone and timber-built foundations. The very tip of a second dry dock (the West Dry Dock) was identified in the southwest corner of the central excavation area while a wood-lined pit, containing a range of artifactual materials, was also encountered near the West Dry Dock remains (Fig. 2).

Aerial view over central excavation area with structures labelled for comparison to Fig. 2 (image by Dennis Swanson,

The large east/west-aligned wall, which can be seen running right to left across the center of Figs. 5 and 6 measured approximately 20 m in length and 2.2 m in width, the upper levels being built of sandstone and the lower levels of limestone ashlar blocks. The wall’s location and form, particularly the section with the acute angled exterior face, appears to correspond to one of a pair of block-like features labelled ‘proposed fortifications’ on Ainslie’s map of 1804 (Fig. 4), which appears later on Kirkwood’s map published in 1817 (Fig. 8). This triangular-shaped feature is denoted on the 1817 map as a ‘Bastion’, appearing to be integrated into the outer sea wall, with a second similar bastion located slightly further along the coast towards Newhaven. Rennie’s observations and design for the new docks (1847a and 1847b) make no specific mention of the word ‘bastion’ or ‘fortification’ and refer simply to a large ‘sea wall’. It remains ambiguous whether Rennie intended the sea wall to be formally fortified and an additional military asset in the harbor’s defence system, complementing the existing Leith Fort, and a Martello Tower, proposed in 1807 to defend the mouth of the harbor from potential seaborne attack (Morris and Barclay 2017, p. 117). The perceived risk of attack during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1779–1815) inspired many ports around Britain to fortify (ibid.). In particular, during 1779, John Paul Jones, a native of Kirkcudbright and an American naval commander, mounted a series of ‘marauding schemes’ (McKeever 2020: p. 1) which included sailing up the Firth of Forth with three warships and threatening to attack Leith (ibid: 16). Fortunately, the attack was thwarted by bad weather but the establishment of Leith Fort, Rennie’s incorporation of bastions in his design of the sea wall, and the design of the Martello tower were clearly intended to ensure that the harbor at Leith would not remain undefended under any future threat. This speaks to the critical importance of Leith’s maritime enterprises not just to Leith itself but to the City of Edinburgh and the surrounding region.

Detail of Robert Kirkwood’s plan of the City of Edinburgh and its environs published by Kirkwood & Son, 1817, annotated with the 2019 excavation boundaries (in blue) and a stylised render of the key structural features exposed (in black) (Map reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland and under Creative Commons (CC BY 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) (Color figure online)

The construction of the sea wall, exposed during excavation (Figs. 4, 6 and 7), was described by Rennie as the first step in a long list of improvements that were intended for the docks as ‘the sea wall being the most tedious and of the greatest consequence, should be first begun’ (Rennie 1847b: 31–32). Rennie’s intention is reported to have been to construct a sea wall similar to that at Scarborough, with the entire frontage built in ashlar-type construction with header and stretcher stones. An order placed in the year 1800 required the stone to be sourced from near to ‘Rosayth’ (modern day Rosyth) Castle in Fife given its durability, and its ability to be extracted in large blocks and worked at a ‘modest’ price (ibid.: 30). Construction of the sea wall was to commence following the 1801 spring equinox and it was estimated to require two years for the completion of the foundation and quay walls (ibid.: 31). Formed against the inner face of the sea wall and running parallel to it was to be a series of three substantial rectangular wet docks (Fig. 4). A pair of dry docks with rounded ends, extending north from the West Wet Dock, are visible on Kirkwood’s 1817 map (Fig. 8).

The ashlar blocks exposed during excavation (Fig. 7) had been produced with a slightly rugged and pecked exterior; each measured 0.8 m in length and was therefore close in size to Rennie’s ideally prescribed three-foot-long pre-cut block. The stones were chamfered and set at a very gentle gradient to create a wider base. Immediately in front of the wall were large vertical timbers, believed to be the remains of the piles of a timber quay gangway described by Rennie (1847b: pp. 31–32).

The West Wet Dock

Set behind the sea wall were Rennie’s East and West Wet Docks, opened in 1806 and 1817 respectively. Both were rectangular and of equal size, measuring 228 m long by 91 m wide and connected by an iron swing bridge (Mowat 2003: p. 298), across a 10.6 m wide entrance (Whyte 1900: p. 294). Rennie’s design suggested the available capacity within each wet dock was sufficient for accommodating 40 ships of 200 tonnes berth, or 100 ships of between 100 and 200 metric tons (Mowat 2003: p. 298), increasing the capacity of the port to unprecedented levels. The far western end of the West Wet Dock was later known as the Queen’s Dock and in 1825 became the Naval Yard. Despite never being extensively used by the Navy, the dock remained as government property until it was absorbed into the dock’s overall complex with the arrival of the Caledonian Rail Company in 1861 (ibid.). During the 2019 excavations, the northern element of the West Wet Dock basin was observed in a WNW–ESE alignment, which would have once continued towards the East Wet Dock (Fig. 2). The wall, exposed to 21 m in length, had survived in good condition with the exception of a few areas of truncation on its upper surface. The wall face was neatly dressed and laid down in an ashlar construction, with metal inserts set at regular 3.5 m intervals along the wall face and abutment for the purpose of mooring vessels within the dock.

The West Dry Dock

Ainslie’s 1804 map depicts the space between the outer sea wall and the West Wet Dock as ‘Intended for Ware Houses which will be a shelter to the docks’ (Fig. 4). Also depicted within this space were two similarly sized dry docks or ‘graving docks’ positioned adjacent to each other and built behind the eastern sea wall bastion (Mowat 2003: p. 298). One source suggests the shipbuilder, Robert Menzies of Menzies and Son, who was also the former owner of the earlier Sandport Street Dock, purchased one of these dry docks in 1806, with the second saved for public use (Mowat 2003: p. 243, 298). A dry dock is essentially a basin with a single entrance to permit vessels to be floated in with water being drained in and out as necessary to facilitate maintenance and modifications, thus providing the facilities required to conduct repairs to extend the lives of vessels (Bottger and Rehler 1964: p. 44). An early account suggests the two dry docks built into the West Wet Dock wall each measured 136 feet long by 45 feet wide at the bottom, and 150 feet long by 70 feet wide at the top, with a 36 feet wide entrance located at the southern end and integrated into the Wet Dock’s northern wall (Groome 1885: p. 484).

Only the very northern extremity of the West Dry Dock was exposed during excavation (see lower left-hand corner of Figs. 5 and 9) but it corresponds to the feature as depicted on various maps and plans from 1817 onwards (Figs. 8, 10 and 11). The very tip of the dry dock was composed of large sandstone blocks, and housed a set of steps leading down into the dock’s basin. This connected to a curving wall with dressed coping slabs forming the rounded northern end of the dry dock structure. The inner facing stones were dressed and carved with tide level lines and a series of metal mooring rings were set into the wall for the purpose of securing vessels. Areas of whinstone cobble setts surrounding the dry dock walls represent the rare survival of pockets of the dock’s original cobble surface. The West Dry Dock remained in use and without major modification until at least 1949 when it still appears on Ordnance Survey mapping (Fig. 12). Despite the inner sea docks, including the West Dock declining in use throughout the second half of the twentieth century due to the increased use of the railways to transport both goods and passengers across the country, the dry docks were kept in operation for ship building and maintenance, with Menzies and Son retaining ownership of the same lease on one of the docks up until it was infilled in 1961, confirming its continued use and maintenance for over 150 years (Mowat 2003: pp. 408–409).

Detail of the West and East Wet Docks and associated Dry Docks depicted on the 1853 (Surveyed 1852) Ordnance Survey map of Edinburgh, Sheet 12, Scale 1:1056, annotated with the 2019 excavation boundaries (in blue) and a stylised render of the key structural features exposed (in black) (Map reproduced reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland and under Creative Commons (CC BY 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) (Color figure online)

Detail of the West and East ‘Old’ Docks and associated Dry Docks Ordnance Survey Map, 1896 (Surveyed 1894) Edinburghshire I.16, 25 inch to the mile, annotated with the 2019 excavation boundaries (in blue) and a stylised render of the key structural features exposed (in black) (Map reproduced reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland and under Creative Commons (CC BY 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) (Color figure online)

Detail of the West and East ‘Old’ Docks from the Ordnance Survey 1:2500 Map (NT2676-A), published 1949, annotated with the 2019 excavation boundaries (in blue) and a stylised render of the key structural features exposed (in black) (Map reproduced reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland and under Creative Commons (CC BY 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) (Color figure online)

A Wood-Lined Pit and its Associated Artefacts

Protected by the layers of made ground, immediately behind the truncated area of the sea wall where the bastion would have re-joined the main harbor wall and to the south-west of the West Dry Dock, was a roughly rectangular wooden pit (Fig. 13), supported in each corner by posts and lined with nailed wooden planks. The pit was cut into the natural clay and contained worked wood and waste material, including wood chips from wood working, perhaps related to a relatively early phase of the docks, probably in the early nineteenth century.

The most extensively worked object from the pit assemblage was a single long piece of either teak (Tectona grandis sp.) or mahogany (Swietenia sp.), with one curved and one straight edge, and which narrowed at each end, with rectangular shapes cut out along its length (Fig. 14A). The function of this item is unknown. Other items from the pit included a possible wheel segment carved from oak (Quercus sp.) (Fig. 14B), a rectangular piece of rift- or quarter-sawn oak plank containing a drilled auger hole (Fig. 15E), and a cylindrical bung made from a non-native species to form a cylinder (Fig. 14C). In addition, a small cork disc was uncovered (Fig. 14D) (Quercus suber sp), also probably functioning as a bung, and a board of a non-native species, possibly teak or mahogany with multiple axe/adze facets and rows of saw marks (Fig. 15F). The non-native species timber objects could possibly relate to interior furnishings of a ship as more accessible European species and would, therefore, be more suitable choices for practical ship components, with other objects relating to offcuts of larger pieces.

All the wooden objects from the pit appear to have been hand sawn and drilled despite steam-powered circular sawing being used from as early as 1777 (Pitt and Goodburn 2003: p. 202). The principal moving parts of large sailing vessels, apart from the rudder assembly, were the various rigging blocks which for any large vessel of the late 18th and early nineteenth century would have numbered as many as 1000 parts (Lavery 1991: p. 153). Wooden items recovered from excavations at West India Docks, London, which are broadly similar in date to those discussed here, have been identified as items related to shoring and rigging parts. They bear similarities to the material found in the pit at Leith, suggesting that some of the items are of a similar character and function (Pitt and Goodburn 2003: p. 202).

Metal items recovered from the same pit included possible ship-building tools such as a round frame bolt or drift bolt with a slightly domed circular head and straight, circular-sectioned shank, broadly similar to examples recovered at the West India Dock Shipyards (ibid 2003: p. 200). Also collected from the pit were fragments of fabric comprised of mixed matted hair fibers characteristic of sheep, lamb, or goat hair fibers, which may be the remains of felt or compressed stuffing for bedding, inter alia, and scraps of partially dyed (blue) wool fibers.

The most significant of the finds recovered from the excavation was a substantially complete rope fender of probable nineteenth century date. Fenders (Fig. 16), as defined by The Seaman’s Dictionary by Sir Henry Mainwaring (1920), are any pieces of old cables, ropes, or billets of wood, which are hung over a ship’s side to keep another ship or boat from rubbing against the vessel and potentially causing damage. This description is from the earliest such dictionary in English, which first appeared in manuscript form between 1620 and 1623 (Mainwaring 1920: p. 146). The late nineteenth century Illustrated Marine similarly describes fenders as ‘anything fit for its purpose, whether a stuffed bag, a piece of spar, etc., suspended from the quay or over the side of a ship or boat to prevent damage through forcible contact’ (Paasch 1890: p. 204).

The fender from the excavation (Fig. 17A, B) was made of a bundle of 2-ply Coir yarns, loosely twisted together to make a soft strand, which was then hitched over a sack containing cork chippings. There would have been a rope lanyard fitted to a loop worked into the top of the fender, which enabled it to be hung over the side of the vessel. This top part of the fender is missing and it is likely it was torn from the rest of the fender, leaving the remainder to drop away. The coir, being more resistant to saltwater, survived whilst the cork stuffing has been lost. It is hard to determine the exact size and shape of the original fender and whether it was round or oval in shape. If round, it may be 36 inches in circumference and would be suitable for a vessel between 25 and 70 feet long. This vessel could have been from any port, not necessarily Leith, and so the fender is not possible as provenance.

Ships’ fenders are made to be used, worn out and thrown away. They are rarely described and their actual forms and methods of construction, ignored by early seamanship works are only briefly described in the twentieth century. Some would be made on board ship, whilst others would be made ashore, either by specialist makers or as an adjunct to the work of ships’ riggers or sailmakers. The find from the excavation is therefore a rare survival. It is likely a side fender that is often called a ships’ cork fender as it was stuffed with cork chippings, although old rope could also be used instead. Cork-filled fenders would be made ashore; specialist makers can be found in late nineteenth century trade directories for large ports, described as fender maker, ships’ fender maker or cork fender maker.

A Change in the Docks

Historic cartographic evidence of the mid-nineteenth century illustrates a major episode of change in the docks area between the early 1820s and the late 1840s (Fig. 10), including the removal of the western-most West Wet Dock, the addition of Victoria Dock to the immediate northeast of the West Wet Dock and the development of the eastern breakwater (not depicted). The area immediately in front of the sea wall is shown as filled in, a fact confirmed by the presence of a deep redeposited clay layer encountered during the excavation. Despite the depiction of the Victoria Dock on early nineteenth century maps, this dock was not opened until 1851 (Marshall 1986: 30). The Victoria Dock temporarily helped lighten the flow of incoming vessels but with increased trade came increased demand on the dock facilities which could not be sustained through the port’s existing layout.

An 1854 report to the Dock’s Commission sets out recommendations for further improvements, noting that expansion to the docks was needed once again. This followed concerns about a lack of capacity to meet the increased demand of ships requiring access, the paucity of low water access for landing passengers, and the absence of a patent slip or graving dock capable of serving large ‘Steamers’ (Mowat 2003: p. 305). The planned improvements included extensions to both breakwater piers, dredging, and the addition of substantial railway network (Groome 1885: p. 485; Mowat 2003: p. 305). The Prince of Wales Dry Dock, to the north-east of the Victoria Dock and on the opposite bank of the Water of Leith, was also constructed in 1853; measuring 116 m by 18 m in size, it was intended to accommodate much larger vessels which were increasingly employed from the early decades of the nineteenth century (Mowat 2003: p. 305).

Situated in the eastern excavation area were the well-preserved remains of an extension to the Eastern Dry Dock (Fig. 18). The basin comprised a large curving wall at its north end with an internal diameter of approximately 20 m, which joined a straight north/south-aligned wall that extended south beyond the excavation area (Fig. 19). The structure was formed of large mortar-bonded sandstone blocks, two courses surviving over the roughly hewn large foundation stones that were cut into clay. A single shallow step was present around the entire internal wall face. The inner facing stones were marked with incised water-level marks and, like the West Dry Dock, had regularly spaced iron rings set into the blocks, every 3.5 m (Fig. 20) and large mooring post was found set into a buttress at the northern extent of the wall. Although the Eastern Dry Dock extension is not specifically mentioned in the available literature, it is visible on the 1876 Ordnance Survey Town Plan (not illustrated) in the same position as an earlier dry dock but extended in length by an additional 36 m (118ft). It was probably around this time that the docks began to be referred to as the East and West ‘Old’ Docks but this is not securely recorded.

With the commissioning of new wet and dry docks, warehouses and customs offices, Rennie’s designs were quickly superseded. This process was evidenced by the layers of redeposited clay interspersed between some of the structural elements exposed during the excavation of 2019, which probably originated from the digging out of the Victoria Dock basin, opened in 1851 to the north-east of the excavation area (Marshall 1986: p. 30). Overlying this clay layer were the partial footprints of various brick and stone-built structures that broadly correspond to warehouses visible on maps from the 1870s onwards.

Discussion

As one of most extensive of Scotland’s major ports to undergo regeneration in the early nineteenth century, the excavations undertaken in 2019 have presented a significant opportunity to reappraise the development of Leith’s harbor and docks during this period. Although the effects of truncation and damage to the early nineteenth century dock structures were visible due to later development of the area, many of the key structures of John Rennie’s harbor design survived but no traces of the earlier medieval and post-medieval port were encountered. By comparing the archaeological evidence with surviving cartographic evidence, it has been possible for four major stages of development of the harbor and docks to be reconstructed, from the late eighteenth century design and early nineteenth century construction of the sea wall through to the final infilling of the various dry and wet docks in the mid-twentieth century. Those four main periods of development can be defined as:

-

Late 18th Century to circa. 1820: design and construction of the sea wall and bastions at the north side of the Water of Leith; creation of two new wet dock basins (known as the East and West Wet Docks) and two dry docks (known as the East and West Dry Docks); construction of various warehouses etc.

-

Circa. 1820 to circa.1850: removal of the western-most wet dock; addition of the Victoria Dock to the northeast and the development of an eastern breakwater; area in front of the sea wall filled in.

-

Circa. 1850 to circa. 1880: construction of the Prince of Wales dry dock to the northeast on the opposite bank of the Water of Leith; early nineteenth century wet docks begin to be known as the ‘old’ docks or ‘Queen’s’ dock; extension to the East Dry Dock; sea wall filled in and built over with the addition of railway infrastructure; arrival of Caledonian Rail Company c.1861; new series of warehouses and quayside buildings constructed over the silt displaced by the earlier construction of the Victoria Dock.

-

Circa. 1900 to circa. 1970: further construction and expansion of railway to service the various wet docks; erection of larger goods stations and continued use of the east and west dry docks into the 1960’s, both being infilled by the early 1970s.

The most prominent feature exposed during the excavation is the sea wall itself; its imposing physical scale and solid mass reflecting its importance as the keystone of the early nineteenth century regeneration of the docks, representing a development from which the docklands grew and expanded, enabling Leith’s port to flourish as a center of trade and industry. As Rennie himself recognized, the construction of the sea wall was a complex and expensive but fundamental structural element in the development of a broad and deep-water quay that could relieve the multiple issues of the previous old harbor (Rennie 1847a: p. 21) and provide the protection against the sea that was needed to support the infrastructure of the port. Its design was intended to dissipate tidal energy during storms by controlling the tide’s ebb and flow towards the area where the Martello Tower was to be built during the first decade of the nineteenth century (Morris and Barclay 2017: p. 117). The sea wall would protect the docks, ships, and warehouses directly behind, and would also act as a viewing point from the bastion, allowing vessels to be tracked in and out of the area (Marshall 1986: p. 35). How the insertion of the dry docks behind the bastions might have compromised their intended function has not been possible to determine during this study but it may reflect a change in focus from a defensive need to the prioritizing of dry dock capacity.

The role of the sea wall in the creation of a deepwater quay was of critical importance as it allowed an increase not only in the number of vessels that could access and be sheltered within the harbor but was deep enough to allow access by even the largest of vessels, which by the end of the eighteenth century reached up to 196 tons (Graham 1977). Comments by Engineer Robert Stevenson in 1814 referenced the success of the dock systems at Leith, Hull, and London, with Dundee noted as ‘peculiarly well adapted’ for such a system where a single large retaining wall would create a significant space for a wet dock system allowing boats to be held at a uniform depth (Stevenson 1847: pp. 206–209).

The incorporation of the wet and dry docks in the harbor was another key component to Rennie’s design, as he stressed the critical need for space for repairing and building ships, emphasising that ships working from Leith were currently built in Hull and that this was to the detriment of Leith’s merchants, traders, and shipwrights (Rennie 1847a: p. 21). A similar problem was later reported by James Rendel with regards to the state of the docks; he suggested a larger graving dock was required to accommodate the larger vessels that in the mid-nineteenth century were being sent to Dundee or even to London to be repaired due to a lack of appropriate facilities at Leith (Mowat 2003: p. 305).

As is demonstrated by the excavated structures and the cartographic evidence, many of the features of Rennie’s early nineteenth century dock design began to be replaced or subsumed within later structures only decades after their construction. In many ways this attests to the success of Rennie’s design which both prompted and facilitated an increase in maritime traffic through Leith’s port and supported the growth of allied industries. The infrastructure of Leith’s port facilities appears at many points to have been insufficient to meet the growth in demands for maritime trade, requiring a rapid series of responsive episodes of further redevelopment and expansion.

The arrival of steam-powered trains and boats into the dock area marks another major turning point for the port (Mowat 2003: p. 306). By the middle of the nineteenth century, the area in front of the sea wall was fully reclaimed from the sea to allow railway infrastructure and warehouses to be installed. Steam-powered trains are thought to have reached the docks by 1849, bringing vital coal to the doorstep of Leith’s industrial hub on a much larger scale than had been possible using horse-drawn carriages and wagons (Marshall 1986: p. 48). This fed local industries such as the Edinburgh and Leith Glassworks and the Victoria Foundry (Hill et al 2018: p. 97), to name a few, and created the appropriate infrastructure for new industries to move into the area, including the Leith Engine Works, established around 1846 (ibid). Contemporary with this, various alterations and extensions to the East and West Dry Docks, as well as the construction of the Prince of Wales Graving docks in the 1860s (completed in 1869) under the direction of James (and later Alexander) Rendel (Jarvis 1996: p. 35), permitted the accommodation of larger steamer vessels which were previously being re-directed elsewhere (Mowat 2003: p. 310).

The remainder of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century saw a change of focus away from Rennie’s original docks, with successive developments extending further out into the Firth of Forth to provide deeper waters and a more maintainable channel (Godden et al 1970: p. 1). The culmination of this development are the impressive working docks of the Port of Leith which still remain today.

During the period when these changes were taking place to Leith’s docklands, many of Scotland’s other major commercial ports such as Aberdeen, Dundee, Glasgow, and Greenock also went through a process of regeneration and growth, and some of the same issues faced by Rennie at Leith were mirrored elsewhere (ScARF 2012: p. 31). Although a bustling center of trade and industry, Glasgow’s port was not free from environmental issues, with vessels frequently denied entry due to the effects of both tide and wind on river levels (Hamlin 1847: p. 499), which restricted the use of the port to a detrimental level and necessitated periodic redevelopment of the dock and its infrastructure. In contrast, Greenock was regarded as one of the saftest ports to enter due to its deepwater geographical setting (ibid: 498–9). A similar picture is presented of the ports of Dundee and Aberdeen, which benefitted from deep water entrances at the mouths of their harbors (Stevenson 1847: pp. 206–209). Dundee’s sea wall construction and dock upgrading did not take place until the 1820s (Leslie 1847: pp. 213–219; Graham 1977: p. 335). In addition, the majority of the larger comparable dock systems seen elsewhere in Scotland were not constructed until later in the nineteenth century: Dundee in 1859, Aberdeen Albert Basin in 1870 (Nicol 1907) and the James Watt Dock in Greenock in 1886 (Wilson 2011: p. 6).

Conclusions

Although many of the dock structures designed and constructed by Rennie in the early nineteenth century have been hidden by later modifications, land reclamation and development, the latest phase of Leith’s development has paradoxically created the opportunity to expose these early features. This has provided a welcome platform to allow the investigation of how the port of Leith flourished from the twelfth century AD through to the modern day, and in particular its significant nineteenth century developments. Although heavily truncated by later structures, the partial remains of the sea wall, the West Wet Dock, the associated East and West Dry Docks survive, and remain as a testament to the importance of Leith’s maritime past and, specifically, to the work of John Rennie. Rennie’s re-design of the Leith docklands can be argued to have made a significant contribution to Scotland’s standing in the world as a major engineering powerhouse, facilitating the growth of the port, its capacity and the industries that sustained it.

By combining the archaeological evidence exposed during the excavations with nineteenth century cartographic sources, it has been possible to glean a more nuanced understanding of the developments of the docks and how these modifications both instigated and reacted to the ebb and flow of maritime trade.

In Rennie’s 1799 report on the state of the docks, he stresses the need for development at Leith to allow the port to flourish via the accommodation of much larger vessels (1847a: p. 12). He also acknowledged the project would unfortunately involve the ‘pulling down’ of a significant number of houses. This was a necessity in his eyes, and he envisaged this would result in a positive change and eventual profit for the residents, workers, and traders of Leith through improvements catalyzed by the construction of larger and more advanced docks (ibid.). The story of the development and regeneration of the docklands continues into the present day with the development works that brought about the need for this investigation.

References

Bottger G, Rehler J (1964) Dry docks through five centuries. Mil Eng 56(369):43–45

Cook M (2001) Tower Street. Leith Discov Excav Scotl N Ser 2:44

Cross-Rudkin PSM (2011) John Rennie and his resident engineers. Proc Inst Civ Eng Eng Hist Herit 164(3):189–193

Gifford J, McWilliam C, Walker D (1984) The buildings of Scotland: Edinburgh. Yale University Press, Yale

Graham A (1977) Old harbors and landing-places on the east coast of Scotland. Proc Soc Antiqu Scotl 108:332–365

Hickman A (2009) Waterfront regeneration in the historic port of Leith: the challenges of maintaining authenticity on an urban scale. Unpublished Dissertation, University of Edinburgh. http://hdl.handle.net/1842/9787 Accessed 12 January 2020

Hill I, Jones C, Barclay R, Gray H (2018) Victoria Foundry, Canal College 2. Excav Discov Excav Scotl N Ser 18:97

Holmes N (1985) Excavations south of Bernard Street, Leith 1980. Proc Soc Antiqu Scotl 115:401–228

Godden R, Land D, Cox P (1970) The Development of Leith Harbor. Proc Inst Civ Eng 45(1):1–33

Groome FH (1885) Leith. Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland Volume 4: 480–494. Grange Publishing Works, Edinburgh. https://digital.nls.uk/gazetteers-of-scotland-1803-1901/archive/97380354 Accessed 12 January 2020

Hamlin, T (1847) Evidence taken before the Tidal Commission on 20th October, 1846 [Greenock], in The Tidal Harbors Commission: Appendix to Second Report of the Commissioners with Supplement and Index, 498–499. London: William Clowes & Sons/HMSO. https://play.google.com/store/books/details/Great_Britain_Tidal_harbors_commission_First_and?id=2jQxAQAAMAAJ Accessed 12 January 2020

Jarvis A (1996) Managing change: the organisation of port authorities at the turn of the twentieth century. North Mariner/le Marin Du Nord 6(2):31–42

Lavery B (1991) Building the wooden walls. The design and construction of the 74 gun warship Valiant. Naval Institute Press, Greenwich

Lawson JA (1995) Burgess street\water street\shore place. Leith Discov Excav Scotl 1995:53

Lawson JA (1999) The Shore. Discov Excav Scotl 1999:42

Leslie J (1847) On the progress of Improvements in Dundee Harbor, 1838, in The Tidal Harbors Commission: Appendix to Second Report of the Commissioners with Supplement and Index, 203–207. London: William Clowes & Sons/HMSO. On-line resource: https://play.google.com/store/books/details/Great_Britain_Tidal_harbors_commission_First_and?id=2jQxAQAAMAAJ Accessed 12 January 2020

Mainwaring GE (ed) (1920) The life and works of Sir Henry Mainwaring. Navy Records Society, London

Marshall J (1986) The life and times of Leith. John Donald Ltd, Edinburgh

Matthews P, Satsangi M (2007) Planners, developers and power: a critical discourse analysis of the redevelopment of Leith Docks. Scotl Plan Pract Res 22(4):495–511

McKeever G (2020) John Paul Jones and the curse of home. Philol Q 99(1):95–117

McNeill PGB, MacQueen HL (1996) Atlas of Scottish history to 1707. University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh

Morris R, Barclay G (2017) The fixed defences of the Firth of Forth in the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, 1779–1815. Tayside Fife Archaeol J 23:109–133

Moore H, Wilson G (2001) Timber Bush/Tower Street, Leith. Discov Excav Scotl N Ser 2:44

Mowat S (1994) The Port of Leith: its history and its people, 1st edn. Forth Ports in association with John Donald Ltd, Edinburgh

Mowat S (1999) Leith, Water Street 1999. Unpublished report

Mowat S (2003) The Port of Leith: its history and its people, 7th edn. John Donald Ltd, Edinburgh

Nicol RG (1907) Aberdeen Harbor. Proc Inst Mech Eng 73(1):575–587

Paasch H (1890) Illustrated maritime encyclopedia. Antwerp, Belgium

Pitt K, Goodburn D (2003) 18th - and 19th -century shipyards at the south-east entrance to the West India Docks, London. Int J Naut Archaeol 32(2):191–209

Reed D, Lawson JA (1999) Ronaldson’s Wharf, Sandport Street Leith. Discov Excav Scot 1999:40

Rennie J (1847) On the state of the Harbor, and the projected Docks and Estimates, 1799, in The Tidal Harbors Commission: Appendix to Second Report of the Commissioners with Supplement and Index, 21–30. London: William Clowes & Sons/HMSO. On-line resource: https://play.google.com/store/books/details/Great_Britain_Tidal_harbors_commission_First_and?id=2jQxAQAAMAAJ Accessed 12 January 2020

Rennie J (1847) Second Report on Leith Harbor and projected Docks, 1800, in The Tidal Harbors Commission: Appendix to Second Report of the Commissioners with Supplement and Index, 30–33. London: William Clowes & Sons/HMSO. On-line resource: https://play.google.com/store/books/details/Great_Britain_Tidal_harbors_commission_First_and?id=2jQxAQAAMAAJ Accessed 12 January 2020

Rossner PR (2011) New avenues of trade: structural change in the European economy and foreign commerce as reflected in the changing structure of Scotland’s commerce, 1660–1760. J Scott Hist Stud 31(1):1–15

ScARF (2012) From Source to Sea. ScARF Marine and Maritime Panel Report. Scottish Archaeological Research Framework. On-line resource: https://scarf.scot/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/2015/12/ScARF%20Source%20to%20Sea%20September%202012.pdf Accessed 27 July 2021

Spanou S (2009) Edinburgh Trams Project: South Leith Parish Church graveyard, Constitution Street, Leith, Volumes I and II. Unpublished archive report prepared by Headland Archaeology (UK) Ltd. https://doi.org/10.5284/1028694 Accessed 12 January 2020

Stevenson R (1847) On the Improvement of the harbor [Dundee], 1814, in The Tidal Harbors Commission: Appendix to Second Report of the Commissioners with Supplement and Index, 203–207. London: William Clowes & Sons/HMSO. On-line resource: https://play.google.com/store/books/details/Great_Britain_Tidal_harbors_commission_First_and?id=2jQxAQAAMAAJ Accessed 12 January 2020

Stronach S (2002) The medieval development of South Leith and the creation of Rotten Row. Proc Soc Antiqu Scotl 132:383–423

Walker J, Cubitt W (1839) Leith Harbor & Docks: plans and reports. Commissioners for the Harbor and Docks of Leith, Edinburgh

Wallace K (2019) Leith Old West (Queen’s) Docks, Leith. Data Structure Report. Unpublished archive report prepared by AOC Archaeology Group on behalf of Cala Homes East Ltd

White P (1900) Leith docks reclamation embankment. Minutes Proc Inst Civ Eng 139:293–294

Wilson D (2011) James Watt Dock, greenock inverclyde archaeological monitoring. Headland Archaeol Data Struct Client Rep on-Line Resour. https://doi.org/10.5284/1019083

Cartographic References

Ainslie, J (1804) Old and New Town of Edinburgh and Leith with the Proposed Docks. Edinburgh (National Library of Scotland Resource: https://maps.nls.uk/towns/rec/415). Accessed 12 January 2020

Kirkwood, R (1817) This Plan of the City of Edinburgh and its Environs. Edinburgh: Kirkwood & Son (National Library of Scotland Resource: https://maps.nls.uk/joins/416.html). Accessed 12 January 2020

Ordnance Survey (1853) (Surveyed 1852) Edinburgh and its Environs Sheet 12, Scale 1:1056 (National Library of Scotland Resource – Town Plans of Scotland, pp 1847–1895; https://maps.nls.uk/view/74415404) Accessed 4 March 2021

Ordnance Survey (1896) (Revised 1894) Edinburghshire (New Series) Sheet I.16, Scale 25 inches to the mile (National Library of Scotland Resource – 25 inch 2nd and later editions, pp 1892–1949; https://maps.nls.uk/view/82877205 ). Accessed 4 March 2021

Ordnance Survey Map (1949) (Revised 1945) Plan 36/2676, Scale 1:2500 (National Library of Scotland Resource – National Grid Maps, pp 1944–1970; https://maps.nls.uk/view/102717329). Accessed 4 March 2021

Acknowledgements

The excavations at Leith Old West Dock were directed by Kai Wallace, with the assistance of fieldwork director, Martin Cook, and Project Manager, Rob Engl for AOC Archaeology Group. The site archaeologists were Harry Francis, Lucy Shinkfield, Inga Edwardson and Andy Tullet Valdez. The author would like to thank Dougie, the Lomond plant operator, for exceptional skill and patience during the excavation. The excavation and post-excavation programme were funded through to publication by CALA Homes (East) Ltd. The author is grateful to John Higgins, Dennis Swanson and Ross Carruthers at CALA and to John Lawson, City of Edinburgh Council Archaeologist, for their advice and guidance from the field to the lab. Special thanks are offered to Des Pawson MBE of the Museum of Knots and Sailors’ Ropework for his valuable insights into the production and use of the fender. The illustrations were prepared by Sam O’Leary and Orlene McIlfatrick and thanks are extended to the National Library of Scotland and Historic Environment Scotland for permission to reproduce the various cartographic and archive images. Aerial images of the docks area courtesy of Dennis Swanson (2019) of CALA Homes East Ltd. Finally, thanks to Dawn McLaren for managing the post-excavation programme and to Mike Roy for commenting on an earlier draft of this paper.

Funding

The excavation and post-excavation analysis was funded in full by CALA Homes (East) Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wallace, K., Crone, A., Wood, A. et al. New Insights into the Development of a Scottish Port: The Archaeological Investigation of Leith’s Nineteenth Century Docklands. J Mari Arch 17, 219–244 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11457-021-09323-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11457-021-09323-y