Abstract

A sample of soil is subjected to multidimensional cyclic loading when two or three principal components of the stress or strain tensor are simultaneously controlled to perform a repetitive path. These paths are very useful to evaluate the performance of models simulating cyclic loading. In this article, an extension of an existing constitutive model is proposed to capture the behavior of the soil under this type of loading. The reference model is based on the intergranular strain anisotropy concept and therefore incorporates an elastic locus in terms of a strain amplitude. In order to evaluate the model performance, a modified triaxial apparatus able to perform multidimensional cyclic loading has been used to conduct some experiments with a fine sand. Simulations of the extended model with multidimensional loading paths are carefully analyzed. Considering that many cycles are simulated (\(N>30\)), some additional simulations have been performed to quantify and analyze the artificial accumulation generated by the (hypo-)elastic component of the model. At the end, a simple boundary value problem with a cyclic loading as boundary condition is simulated to analyze the model response.

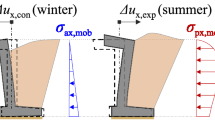

Adapted from Fuentes [16]

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Andersen K (2009) Bearing capacity under cyclic loading-offshore, along coast, and on land. The 21st Bjerrum lecture. Can Geotech J 46(5):513–535

Andersen K, Lauritzsen R (1988) Bearing capacity for foundation with cyclic loads. J Geotech Eng ASCE 114(5):540–555

Andersen K, Lauritzsen R (1989) Model tests of offshore platforms II. Interpretation. J Geotech Eng ASCE 115(11):1550–1568

Badellas A, Savvaidis P, Tsotos S (1988) Settlement measurement of a liquid storage tank founded on 112 long bored piles. In: Second international conference on field measurements in geomechanics, Kobe, pp 435–442

Bauer E (1992) Zum mechanischem verhalten granularer stoffe unter vorwiegend ödometrischer beanspruchung. In: Veröffentlichungen des Institutes für Bodenmechanik und Felsmechanik der Universität Fridericiana in Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe, Germany, Heft 130, pp 1–13

Bauer E (1996) Calibration of a comprehensive constitutive equation for granular materials. Soils Found 36(1):13–26

Bernardie S, Foerster E, Modaressi H (2006) Non-linear site response simulations in Chang-Hwa region during the 1999 Chi-Chi earthquake, Taiwan. Soil Dyn Earthq Eng 26(11):1038–1048

Bjerrum L (1973) Geotechnical problems involved in foundations of structures in the North Sea. Géotechnique 23(3):319–358

Borja R, Tamagnini C, Amorosi A (1997) Coupling plasticity and energy conserving elasticity models for clays. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng ASCE 123(10):948–957

Boyce H (1980) A non-linearmodel for the elastic behaviour of granular materials under repeated loading. In: Pande GN, Zienkiewicz OC (eds) Soils under cyclic and transient loading. A.A. Balkema, Swansea, pp 285–294

Dafalias Y (1986) Bounding surface plasticity. I: mathematical foundation and hypoplasticity. J Eng Mech ASCE 112(9):966–987

Dafalias Y, Herrmann L (1982) Bounding surface formulation of soil plasticity. In: Pande G, Zienkiewicz O (eds) Transient and cyclic loads, chapter 10. Wiley, New York, pp 253–282

El Far A, Davie J (2008) Tank settlement due to highly plastic clays. In: Prakash S (ed) Sixth International conference on case histories in geotechnical engineering, MI University, Arlington, p 32

Fellenius B, Ochoa M (2013) Large liquid storage tanks on piled foundations. In: Hai NM (ed) International conference on foundation on soft ground engineering-challenges in the Mekong Delta, HoChiMinh City, pp 3–17

Finn W (2000) State-of-the-art of geotechnical earthquake engineering practice. Soil Dyn Earthq Eng 20(1–4):1–15

Fuentes W (2014) Contributions in Mechanical Modelling of Fill Materials. Schriftenreihe des Institutes für Bodenmechanik und Felsmechanik des Karlsruher Institut für Technologie, Heft 179

Fuentes W, Triantafyllidis T (2015) ISA model: a constitutive model for soils with yield surface in the intergranular strain space. Int J Numer Anal Methods Geomech 39(11):1235–1254

Fuentes W, Triantafyllidis T, Lizcano A (2012) Hypoplastic model for sands with loading surface. Acta Geotech 7(3):177–192

Gajo A (2009) Hyperelsatic modelling of small-strain stiffness anisotropy of cyclically loaded sand. Int J Numer Anal Methods Geomech 34(2):111–134

Gazetas G (1983) Analysis of machine foundation vibrations: state of the art. Soil Dyn Earthq Eng 2(1):2–42

Herle I, Gudehus G (1999) Determination of parameters of a hypoplastic constitutive model from properties of grain assemblies. Mech Cohesive-Frict Mater 4(5):461–486

Herle I, Kolymbas D (2004) Hypoplasticity for soils with low friction angles. Comput Geotech 31(5):365–373

Huber G (1988) Erschtterungsausbreitung beim Rad/Schiene-System. Institut für Bodenmechanik und Felsmechanik der Universität Fridericiana in Karlsruhe, Heft Nr. 115

Hughes TJR (1998) Classical rate-independent plasticity and viscoplasticity. In: Marsden JE, Sirovich L, Wiggins S (eds) Computational inelasticity, vol 7. Springer, New York

Iraji A, Farzaneh O, Hosseininia E (2014) A modification to dense sand dynamic simulation capability of Pastor–Zienkiewicz–Chan model. Acta Geotech 9(2):343–353

Ishihara K (1993) Liquefaction and flow failure during earthquakes. The 33rd Rankine lecture. Géotechnique 43(3):351–415

Kim D-S, Lee J-S (2000) Propagation and attenuation characteristics of various ground vibrations. Soil Dyn Earthq Eng 19(2):115–126

Kolymbas D (1988) Eine konstitutive Theorie für Boden und andere körmige Stoffe. Habilitation Thesis, Universität Karlsruhe, Germany. Institut für Boden- und Felsmechanik, Heft 109

Li Z, Kotronis P, Escoffier S, Tamagnini C (2016) A hypoplastic macroelement for single vertical piles in sand subject to three-dimensional loading conditions. Acta Geotech 11(2):373–390

Luco J, Westmann R (1972) Dynamic response of a rigid footing bonded to an elastic half space. J Appl Mech 39(2):169–193

Masin D (2005) A hypoplastic constitutive model for clays. Int J Numer Anal Methods Geomech 29(4):311–336

Matsuoka H, Nakai T (1977) Stress–strain relationship of soil based on the SMP. In: Proceedings of speciality session 9, IX international conference on soil mechanic foundation engineering, Tokyo, 1977, pp 153–162

Mroz Z (1967) On the description of anisotropic workhardening. J Mech Phys Solids 15(3):163–175

Mroz Z (1969) An attempt to describe the behavior of metals under cyclic loads using a more general working hardening model. Acta Mech 7:199–212

Mroz Z, Norris A, Zienkiewicz O (1978) An anisotropic hardening model for soils and its application to cyclic loading. Int J Numer Anal Methods Geomech 2(3):203–221

Mylonakis G, Nikolaou S, Gazetas G (2006) Footings under seismic loading: analysis and design issues with emphasis on bridge foundations. Soil Dyn Earthq Eng 26(9):824–853

Niemunis A (2003) Extended Hypoplastic Models for Soils. Habilitation, Schriftenreihe des Institutes für Grundbau und Bodenmechanil der Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Germany, 2003. Heft 34

Niemunis A (2008) Incremental driver, user’s manual. University Karlsruhe KIT, Karlsruhe

Niemunis A, Cudny M (1998) On hyperelasticity for clays. Comput Geotech 23(4):221–236

Niemunis A, Herle I (1997) Hypoplastic model for cohesionless soils with elastic strain range. Mech Cohesive-Frict Mater 2(4):279–299

Osinov VA, Chrisopoulos S, Triantafyllidis T (2013) Numerical study of the deformation of saturated soil in the vicinity of a vibrating pile. Acta Geotech 8(4):439–446

Oztoprak S, Bolton MD (2013) Stiffness of sands through a laboratory test database. Géotechnique 63(1):54–70

Pastor M, Zienkiewicz O, Chan A (1990) Generalized plasticity and modeling of soil behavior. Int J Numer Anal Methods Geomech 14(3):151–190

Poblete M, Wichtmann T, Niemunis A, Triantafyllidis Th (2011) Accumulation of residual deformations due to cyclic loading with multidimensional strain loops. In: 5th international conference on earthquake engineering, Santiago, Chile, January 2011

Poblete M, Wichtmann T, Niemunis A, Triantafyllidis Th (2015) Caracterización cíclica multidimensional de suelos no cohesivos. Obras y Proyectos 17:31–37

Rascol E (2009) Cyclic properties of sand: dynamic behaviour for seismic applications. Ph.D. thesis, École Polythecnique Fédérale de Lausanne

Richart F, Hall J, Woods R (1970) Vibrations of soils and foundations. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Richart F, Whitman R (1967) Comparison of footing vibration tests with theory. J Soil Mech Found Div ASCE 93(6):143–168

Shi X, Herle I (1010) Numerical simulation of lumpy soils using a hypoplastic model. Acta Geotech. doi:10.1007/s11440-016-0447-7

Siddiquee M (2015) A pressure-sensitive kinematic hardening model incorporating masing’s law. Acta Geotech 10(5):623–642

Simpson B (1992) Retaining structures: displacement and design. Géotechnique 42(4):541–576

Triantafyllidis Th, Wichtmann T, Fuentes W (2013) Zustände der grenztragfähigkeit und gebrauchstauglichkeit von böden unter zyklischer belastung. In: Schanz T, Hettler A (eds) Aktuelle Forschung in der Bodenmechanik 2013. Springer, Berlin, pp 147–176

Vermeer P (1982) A five constant model unifying well established concepts. In: Gudehus G (ed) International workshop on constitutive relations for soils, Grenoble, pp 175–198

Wegener D, Herle I (2014) Prediction of permanent soil deformations due to cyclic shearing with a hypoplastic constitutive model. Acta Geotech 37:113–122

Weifner T, Kolymbas D (2007) A hypoplastic model for clay and sand. Acta Geotech 2(2):103–112

Whitman R, Richart F (1967) Design procedures for dynamically loaded foundations. J Soil Mech Found Div ASCE 93(6):169–193

Wichtmann T (2005) Explicit accumulation model for non-cohesive soils under cyclic loading. Dissertation, Schriftenreihe des Institutes für Grundbau und Bodenmechanik der Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Heft 38. www.rz.uni-karlsruhe.de/~gn97/

Wichtmann T, Niemunis A, Triantafyllidis Th (2013) On the “elastic” stiffness in a high-cycle accumulation model—continued investigations. Can Geotech J 50(12):1260–1272

Wolffersdorff V (1996) A hypoplastic relation for granular materials with a predefined limit state surface. Mech Cohesive-Frict Mater 1(3):251–271

Wu W, Bauer E (1994) A simple hypoplastic constitutive model for sand. Int J Numer Anal Methods Geomech 18(12):833–862

Wu W, Niemunis A (1996) Failure criterion, flow rule and dissipation function derived from hypoplasticity. Mech Cohesive-Frict Mater 1(2):145–163

Zienkiewicz O, Mroz Z (1984) Generalized plasticity formulation and application to geomechanics. In: Desai C, Gallagher R (eds) Mechanics of engineering materials. Wiley, New York, pp 655–679

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Hypoplastic model from Wolffersdorff

The general equation of the hypoplastic model by Wolffersdorff [59] can be written as:

whereby \(\bar{\mathsf{E}}\) is the “linear” stiffness and \(\bar{{\varvec{\varepsilon }}}^p\) is the hypoplastic strain rate defined in the sequel. According to the ISA + HP nomenclature, the tensor \(\mathsf{E}\) is referred as the mobilized stiffness and \(\bar{{\varvec{\varepsilon }}}^p\) as the mobilized plastic strain rate. The definition of \(\bar{\mathsf{E}}\) reads [59]:

whereby \(\hat{{\varvec{\sigma }}}= {\varvec{\sigma }}/\mathrm{tr}{\varvec{\sigma }}\) is the relative stress, \(f_b\), \(f_e\), F and a are scalar factors and \(\mathsf{I}\) is the fourth-order tensor for symmetric second-order tensors. The scalar factor F is responsible for the Matsuoka–Nakai shape of the critical state surface and is defined as:

whereby the factors a, \(\theta \) and \(\psi \) are defined as:

The tensor \({\varvec{\sigma }}^*\) is the deviator stress tensor and \(\varphi _c\) is the critical state friction angle. The model incorporates the characteristic void ratios corresponding to the maximum \(e_i\), minimum \(e_d\) and critical \(e_c\), respectively. They follow the function proposed by Bauer [5] depending on the mean pressure p:

where \(e_{i0}\), \(e_{d0}\) and \(e_{c0}\) are parameters representing the characteristic void ratios at \(p=0\) and \(h_s\) and \(n_B\) are additional parameters to fit these curves. The scalar functions \(f_e\) and \(f_b\) read:

whereby \(\beta \) and \(\alpha \) are material parameters The mobilized plastic strain rate \( \dot{\bar{\varvec{\varepsilon }}}^p\) is defined as:

whereby tensor \(\bar{\mathbf {N}}\) reads:

and the factor \(f_d\) follows the relation:

Details of these functions are explained in [37]. The required parameters are briefly described in the following appendix.

Appendix 2: Short guide to determine the ISA + HP parameters

The ISA + HP model (without the proposed extension) requires the calibration of 12 parameters. In this appendix, a short guide for their determination is provided.

-

The critical state friction angle \(\varphi _c\) can be adjusted with points of a triaxial compression test after a vertical strain of \(\varepsilon _1>25\,\%\). The critical state slope within the \(p-q\) space can be calibrated with the relation \(q/p=6\sin \varphi _c/(3-\sin \varphi _c)\) for these points.

-

The maximum void ratio at \(p=0\) denoted with \(e_{i0}\) can be obtained through the standardized minimum density test (ASTM D4254-14).

-

The exponent \(n_B\) can be adjusted to match the elastic stiffness dependence with the mean pressure \(G\sim p^{1-n_B}\) through the results of resonant column test for different confining pressures. If the experiments are scarce, some values from the literature can be adopted, e.g., \(n_B=0.5\) [47].

-

The granular hardness \(h_s\) can be adjusted to simulate the oedometric compression stiffness under very loose states \(e\approx e_i\) where \(e_i=e_i(p)\) is the maximum void ratio curve. A method to determine \(h_s\) given some oedometric results is described by Herle and Gudehus [21].

-

The critical state void ratio at \(p=0\) denoted with \(e_{c0}\) can be adjusted from points lying at the critical state (\(\varepsilon _1>25\,\%\) with triaxial compression) in the \(e-p\) space with very low pressure \(p<20\hbox { kPa}\). When data are scarce, one may adopt the approximation \(e_{c0}\approx 0.9 e_{i0}\).

-

The dilatancy exponent \(\alpha \) is calibrated with the behavior of medium-dense and dense samples sheared through drained triaxial compression. This parameter controls the dilatancy rate of the volumetric strains after reaching the phase of transformation line. A relation to determine \(\alpha \) with drained triaxial test is described by Herle and Gudehus [21].

-

The barotropy exponent \(\beta \) is adjusted to dense samples compressed under oedometric conditions. Herle and Gudehus [21] provided an equation to determine this parameter.

-

The parameter R defines the size of the elastic locus in terms of strain increments. For the secant shear stiffness \(G^\mathrm{sec}\), this can be interpreted as the strain range at which no degradation occurs. Many experiments point a value of approximately \(\parallel \Delta {\varvec{\varepsilon }}\parallel \approx 10^{-5}\) for sands, but as mentioned in [17], a small value of this parameter may lead to numerical difficulties when dealing with finite element simulations. Hence, a value of \(\parallel \Delta {\varvec{\varepsilon }}\parallel > 5\times 10^{-5}\) is recommended.

-

The parameter \(\beta _h\) controls the needed strain increment to eliminate the influence of the intergranular strain effect in the model. In other words, it controls the size of the strain amplitude at which no “small strain effects” is simulated by the model. The equation relating this strain amplitude with the parameter \(\beta _h\) was provided in [17] and reads:

$$\begin{aligned} \beta _h=\dfrac{\sqrt{6}R(\log (4)-2\log (1-r_h))}{6\Delta \varepsilon _s-\sqrt{6} R(3+r_h)} \end{aligned}$$(32)where \(\Delta \varepsilon _s\) is the deviatoric strain amplitude and \(r_h\approx 0.99\) is a factor which defines how close is tensor \(\mathbf {c}\) to its bounding condition \(r_h=\parallel \mathbf {c}\parallel /\parallel \mathbf {c}_b\parallel \).

-

The parameter \(\chi \) controls the degradation curve shape of the secant shear modulus \(G^\mathrm{sec}\). Its calibration can be performed simulating some cycles of triaxial test as explained in [17].

-

The parameter \(C_a\) controls how fast the plastic accumulation rate reduces upon the cycles. It can be adjusted with a cyclic undrained triaxial test with the behavior of the accumulated pore pressure \(p^\mathrm{acc}_w\) versus the number of cycles N. The first portion of this curve, with approximately \(N<10\), can be adjusted through parameter \(C_a\) by trial and error. An example of its calibration is given in Fig.14c.

-

The parameter \(\chi _{\max }\) controls the accumulation rate when the number of consecutive cycles is large, of about \(N>10\). It can be adjusted with a cyclic undrained triaxial test with the behavior of the accumulated pore pressure \(p^\mathrm{acc}_w\) versus the number of cycles N. An increasing number of \(\chi _{\max }\) would return a lower value of N to reach failure at the critical state line. It can be adjusted by trial and error after fixing \(C_a\). An example of its calibration is given in Fig. 14d.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Poblete, M., Fuentes, W. & Triantafyllidis, T. On the simulation of multidimensional cyclic loading with intergranular strain. Acta Geotech. 11, 1263–1285 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-016-0492-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-016-0492-2