Abstract

The Every Student Succeeds Act supports personalized learning (PL) to close achievement gaps of diverse K-12 learners in the United States. Implementing PL into a classroom entails a paradigm change of the educational system. However, it is demanding to transform traditional practice into a personalized one under the pressure of the annual standardized testing while it is unclear which PL approaches are more likely to result in better academic outcomes than others. Using national survey data of ELA teachers in identified learner-centered schools, this study compared high and low-performing learner-centered schools (determined by their standardized test results) in terms of their use of five PL features (personalized learning plan, competency-based student progress, criterion-referenced assessment, project- or problem-based learning, and multi-year mentoring) and their use of technology for the four functions of planning, learning, assessment, and recordkeeping. Generally, teachers in high-performing schools implemented PL more thoroughly and utilized technology for more functions than those in low-performing schools. Teachers in high-performing schools more frequently considered career goals when creating personal learning plans, shared the project outcomes with the community, and assessed non-academic outcomes. They stayed longer with the same students and developed close relationships with more students. Also, they more frequently used technology for sharing resources and reported having a more powerful technology system than those in low-performing schools. This study informs educators, administrators, and researchers of which PL approaches and technology uses are more likely to result in better academic outcomes measured by standardized assessments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The International Association for K-12 Online Learning (iNACOL)Footnote 1 claimed that “K-12 education is at the beginning of what many hope will be a systemic transformation toward personalized learning” (Patrick et al. 2016b, p. 1). The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) of 2015 promotes personalized learning (PL) as a way to close the achievement gaps (U.S. Department of Education 2015). Adopting personalized learning takes a systemic transformation of the entire school system (Patrick et al. 2016a; Reigeluth and Karnopp 2013). The Race to the Top Program funded states and school districts to undergo systemic educational reform to develop a localized PL plan unique to their district (U.S. Department of Education 2012a). The promotion of PL has been reinforced by the U.S. Department of Education’s National Education Technology Plan (2010, 2017), emphasizing the roles of technologies in creating an effective PL environment and providing guidance on how to utilize technology for PL.

Despite the encouragement and support, transforming to a learner-centered, PL system could be particularly challenging, given that the U.S. educational system had been under heavy influence of the No Child Left Behind (NCBL) Act of 2001. Under NCLB, public schools had to administer a standardized test to all students from Grade 3 and up. If adequate yearly progress was not made, consequences followed, such as change in leadership or school closure (U.S. Department of Education 2001). The high-stakes testing and accountability placed much pressure on teachers and administers and changed the instructional culture of schools. Teachers who used learner-centered approaches had to abandon their practices and shift to teaching to the test (Center on Education Policy 2007; Hursh 2007). Teachers experienced distress and dissatisfaction, not only in high-minority and low-income schools but in all schools in the school district surveyed by Smith and Kovacs (2011).

Although ESSA encourages educators to adopt PL as their instructional practice, they are still under pressure of standardized testing because ESSA still requires annual testing. Meanwhile, there is growing evidence that personalized, learner-centered approaches such as project- or problem-based learning can significantly enhance learning outcomes. For example, students at the NYC School of One that employed the personalized learner-centered paradigm significantly outperformed their peers in traditional classes (Research & Policy Support Group 2010). Also, in a large-scale comparative study, Han et al. (2014) found that using carefully designed and implemented project-based learning was effective in increasing low-achievers’ academic achievement in math, measured by the state standardized test.

Although there is growing evidence of effectiveness of certain PL approaches, there is a paucity of systematic research on how different PL practices are associated with academic performance on standardized tests. This is essential especially for educators who are to adopt PL, yet need to demonstrate satisfactory performance in the standardized tests. When done alone, it is challenging to envision PL in a day-to-day practice and transform their instructional practices (District Reform Support Network 2016; Gross et al. 2018). More pressure is placed when test scores are involved. There could be doubt, concerns, and a lack of information as to which PL practices promote improvements in academic performance.

To fill the void, this study identified learner-centered schools in the U.S., collected standardized testing results of those schools, and compared PL practice and technology use between high and low-performing schools using national survey data of teachers in the learner-centered schools. This study aims to answer the following research question: Which kinds of personalized learning practices and technology use are different between academically high-performing and low-performing learner-centered schools? The findings will inform educators and researchers of which particular PL practices and technology use differentiate high-performing schools from low-performing schools.

Literature review

As a broad paradigm of education, the learner-centered paradigm focuses on individual learners and helps them construct their own knowledge (Lambert and McCombs 1998; McCombs 2013). PL is a fearture in the paradigm that has been spotlighted as a way to customize learning for individual learners (McCombs 2008). Our literature review revealed an increasing number of publications related to PL. In Li and Wong (2019)’s systemic review of 179 studies from 2009 to 2018, there was a 120% increase in the number of studies from the 2009 to 2013 period to the 2014–2018 period. Our search of literature after 2019 revealed exponentially increased results. Our reviews showed that although the topics were becoming more diversified than before, most of the articles were focused on teaching guidelines and implementing emerging technologies such as learning analytics or augmented reality for PL (e.g., Lin et al. 2013; Ma et al. 2016; Maseleno et al. 2018), rather than on PL’s academic outcomes and its relation to standardized testing. Only a handful of studies investigated PL practice in K-12 or its relationship with academic achievement, especially at the national level: two in the U.K. (Sebba and Britain 2007; Underwood et al. 2007) and two in the U.S. (Gross et al. 2018; WestEd 2006), possibly due to the difficulty of obtaining large-scale comprehensive national data related to academic achievement, particularly in personalized learning.

The U.K. Department for Education launched the Five Year Strategy for Children and Learners for England in 2004 to promote PL practices from elementary through post-secondary institutions (Department for Education and Skills 2004). Funded by the U.K. Department for Education, two national studies were conducted: Sebba and Britain (2007) and Underwood et al. (2007). These two studies used a large-scale national data set to reveal comprehensive aspects of PL, including academic testing and achievement. It is worthwhile reviewing closely how these rare studies were conducted to compare PL practices between the U.S. and the U.K.

First, Sebba and Britain (2007) investigated K-12 schools’ PL approaches based on Miliband (2006) five components of PL. Miliband (2006) previously identified the five components of PL (1) assessment for learning, (2) effective teaching and learning, (3) curriculum entitlement and choice, (4) school organization, and (5) beyond the classroom—by utilizing a survey method and case studies, which became the basis of Sebba and Britain (2007) analysis.

Sebba and Britain (2007) examined how schools adopted PL initiated by the Five Year Strategy for Children and Learners in a nationally representative sample of K-12 schools in the U.K. A stratified sample by school size and region was drawn. Of the total of 2,838 schools, 347 provided valid responses, giving a response rate of 12.2 percent. After the survey, 13 case studies were undertaken in schools with promising PL practice by collecting documentation, conducting interviews with managers, teachers, teaching assistants, students, parents and governors, and observing lessons and activities.

Sebba and Britain (2007) found that many schools were using the following learner-centered instructional approaches: collaborative learning (88%), inquiry-based learning (69%), teaching to preferred learning styles (66%), encouragement of autonomy and choices (64%), and classes grouped by ability (41%). Regarding assessment, more than 80% of the schools responded that they generally engaged in providing individual feedback (94%), individual setting of targets (92%), self and peer assessment (86%), and academic tracking (81%). Also, 45% of schools utilized technology in assessing students. In contrast, in their case studies, they found that assessment was not consistently embedded in learning in most of the case-study schools.

Sebba and Britain (2007) further showed that across all types of schools, teachers indicated that the following factors positively affect academic achievement: ongoing assessment for learning, target setting for individual learning, tracking student progress, and self and peer assessment. Primary teachers mentioned small-group, targeted, intervention strategies such as catch up and booster programs. Teachers in a few secondary schools mentioned vocational or alternative pathways and curriculum flexibility. Sebba and Britain (2007) study was useful in identifying effective instructional and assessment strategies for PL.

Another national study on PL conducted in the U.K, Impact 2007: Personalizing Learning with Technology, was commissioned by the British Educational Communications and Technology Agency utilizing a survey and case studies (Underwood et al., 2007). The purpose of the study was to gather information about perceptions of the progress in personalization of teachers and students as a result of the Five Year Strategy.

Underwood et al. (2007) used survey data from 67 schools. Those schools were mostly evenly distributed in terms of school levels (primary and secondary), technology maturity (high and low), and location (rural and urban). Multilevel modeling was applied to examine relationships between PL practice and various other factors. Results suggest that primary teachers were more encouraged and responded more positively about practicing PL than secondary teachers. Mathematics teachers were more negative about practicing PL than teachers in other subjects. Interestingly, students in academically better performing secondary schools tended not to perceive a strong personalizing agenda in their schools.

The case studies by Underwood et al. (2007) entailed school visits, two classroom observations, and interviews with participating teachers in a representative sample of 24 schools. Instructional activities observed included using project-based learning, computer-supported collaborative learning, computer-based instruction, and learning beyond the national curriculum. Assessment activities included online self-assessment, individual target setting, providing support to meet the target, and monitoring students’ own individual performance.

In the U.S., WestEd (2006) conducted a national study using a case study method for the U.S. Department of Education on the practice of exceptional charter high schools. This study was not conducted to investigate PL practice in those schools per se, but some of the common themes found in the schools were aligned with PL practices.

Based on recommendations from their advisory group and review of achievement data, they identified 70 charter schools, which were narrowed down to 26 that demonstrated high academic performance and increasing achievement with a high portion of low-income or minority population of students. Finally, eight schools were selected based on demographic variation, promising practices, geographic location, and achievement data.

A one- or two-day site visit was made to each school. In each school, informal observations throughout the school and interviews were conducted with students, parents, teachers, board members, administrators and school partners. Also, documents, including school schedules, sample assessments, lesson plan forms, teacher planning protocols, newsletters, application forms, brochures, charter plans, and report cards, were analyzed.

WestEd (2006) observed four prominent PL features across the schools: (1) providing real-world experiences to students, (2) teaching for mastery, (3) developing self-regulation and meta-cognitive skills, and (4) assessment-data-driven teaching. At the schools, students were encouraged to broaden their experiences and learn beyond the classroom. Students were engaged in various real-world experiences, including working as interns, traveling to different cultures, organizing school events, and attending college courses, which provided relevant and meaningful learning experiences.

Teaching for mastery entailed the expectation that students reach mastery to move on to the next academic level. Remediation or acceleration was given to students depending on their mastery levels. For example, at one school, ninth graders had four opportunities to pass proficiency exams in reading, writing, and math, and when not meeting the proficiency levels, they were retained and additional academic support was provided. Although extensive tutoring and academic support were available, there was great awareness and emphasis on becoming an independent, self-regulated learner, and teachers helped students develop their study skills; thus developing self-regulation and metacognitive skills was the third component.

Finally, assessment data-driven teaching provides the standards and guidelines for personalized teaching. Teaching to mastery requires ongoing assessment and data-driven teaching. In the schools, lessons were revised continuously according to students’ needs identified by assessments. For example, at one school, teachers used assessments to understand student needs and incorporated the results into the instructional planning process and decision-making process at the school level. For instance, when there were students with a low level of achievement in math, two additional tutors were added to the math classroom.

Another U.S. study, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, provided a more general picture of PL in K-12 education in the U.S. (Gross et al. 2018). It surveyed national samples of students and teachers as well as teachers in the schools funded by the foundation to transform to a PL system. A total of 908 teachers from 38 schools responded.

The study’s (Gross et al. 2018) results suggest that nearly 80% of elementary and middle school teachers indicated a low level of implementation of competency-based student progress. However, 91% reported having one-on-one or small-group discussion with some or all students. Only a third of students reported that they set their own learning goals at least half the time. This is in line with only 19% to 29% of teachers reporting that most of their students set their unique learning goals. Also, most teachers were reluctant to give students control of their learning in terms of pacing, content, and learning activities. In interviews, teachers mentioned pressure to meet learning standards as a major concern that inhibited the transition.

Summary of literature review

Our literature review sheds light on some interesting yet contradictory findings about PL practice. In the U.K, high-performing schools were reluctant to transition to a PL system (Underwood et al. 2007). In the U.S., most teachers studied had not yet implemented competency-based student progress or allowed students to take control of their own learning, because of the pressure of meeting academic standards, according to a national survey (Gross et al. 2018). However, some teachers in the U.K. perceived some features related to competency-based student progress to be positively related to academic achievement, such as ongoing assessment for learning, target setting for individual learning, tracking student progress, and self and peer assessment, according to the national study by Sebba and Britain (2007). Also, case studies of successful charter schools reported PL practices as key characteristics of outperforming schools including providing real-world experiences to students, teaching for mastery, and developing self-regulation (WestEd 2006).

While a few national-level U.S and U.K. research studies have enlightened some aspects of PL practices, there is still a dearth of research with regard to which PL practices and technology uses can lead to high performance in academic testing. With the pressure to achieve immediate results in external measures such as standardized tests (La Velle and Flores 2018), educators, including teachers and administrators, need more systematic research evidence that demonstrates the relationship between various features of PL practice and academic achievement in schools. To address the knowledge gap, this study aims to draw evidence by comparing academically high-performing and low-performing learner-centered schools in the U.S regarding their differences in PL practice and technology use.

Conceptual framework for PL practice

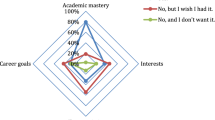

Lee (2014) suggested five essential features that serve as design principles for PL seen in Fig. 1: (1) a personalized learning plan (PLP) that takes individual differences into account, (2) competency-based student progress (CBSP) rather than time-based progress, (3) criterion-referenced assessment (CRA) rather than norm-referenced assessment for ongoing formative and summative assessment, (4) project- or problem-based learning (PBL), and (5) multi-year mentoring (MYM) of students by a teacher or a mentor. We used this as our conceptual framework for PL practice, as it includes elements for instruction, assessment, and system structure for PL.

Adapted from Lee (2014)

Design Principles of Personalized Learning.

A PLP takes into account individual differences or needs such as career goals, characteristics, interests, and academic mastery. Creating PLPs allow learning to be relevant, interesting and appropriate to the learners, which can make learning effective and engaging (American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force on Psychology in Education 1993; Bransford et al. 2000). The PL Framework by LEAP Innovations (2020) includes learning towards personal learning goals based on a deep understanding of the learner’s academic needs, interests, strengths and other characteristics.

CBSP refers to individual student progress based on one’s academic mastery, in contrast to the current practice of time-based student progress (Software & Information Industry Association 2010; U.S. Department of Education, n.d.). This is a key element in the educational reform movement for PL (Miliband 2006; Software & Information Industry Association 2010; U.S. Department of Education, n.d.), and several PL frameworks include this component as an essential feature of PL (LEAP Innovations 2020; Miliband 2006; Software & Information Industry Association 2010; WestEd 2006). Carroll (1963) argued that having all students spend the same amount of time would result in a high correlation between students’ aptitude and achievement, accordingly failing students with low aptitude levels. The U.S. Department of Education (2012b) has recognized the two-sigma problem that Bloom (1984) identified, and has argued that CBSP can be implemented at affordable costs on a large scale with the recent advances in technology (U.S. Department of Education 2012b).

CRA evaluates students’ mastery of a certain skill or competency, whereas norm-referenced assessment reports a student’s performance in comparison to a group of similar students (Thorndike and Thorndike-Christ 2010). Ongoing formative assessment has been emphasized as a way to understand students’ learning needs and track students’ progress towards learning goals (American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force on Psychology in Education 1993; LEAP Innovations 2020; Miliband 2006; Sturgis and Patrick 2010). CRA is more appropriate for the purposes of ongoing assessment than a norm-referenced assessment as it helps identify learning needs and determine mastery of the current topic (Sturgis and Patrick 2010).

PBL is a learner-centered instructional approach that engages learners in an authentic, complex, ill-structured, and open-ended inquiry. PBL has been recommended as an effective way to customize instruction for individual learners (Software & Information Industry Association 2010; U.S. Department of Education 2010), and several PL frameworks include PBL or real-world, inquiry-driven experiences as an essential component (LEAP Innovations 2020; Miliband 2006; Software & Information Industry Association 2010; WestEd 2006). PBL can be implemented in various ways individually or in groups with various student activities and assessment methods (Bell 2010; Duch et al. 2001; Gijbels et al. 2005; Hmelo-Silver 2004; Jonassen 2000, 2004; Savery 2006; Şendağ and Ferhan Odabaşı 2009; Wirkala and Kuhn 2011).

MYM refers to teachers mentoring the same student for more than one year. Major benefits include (1) the teacher knows the students well enough to take their individual needs into account as emphasized in the APA principles (American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force on Psychology in Education 1993) and (2) the teacher can build a closer relationship with their students (George et al. 1987) as deemed critical by LEAP Innovations (2020).

Conceptual framework for a technology system

Reigeluth et al. (2015) proposed a conceptual framework for a technology system that supports PL, entitled Personalized Integrated Educational System (PIES). The four major functions of PIES are (1) recordkeeping, (2) planning, (3) instruction, and (4) assessment.

The recordkeeping function collects student data, including academic data such as masteries of certain topics and nonacademic data such as interests, characteristics, backgrounds, career goals and more to inform the development of PLPs. The planning function helps teachers develop a PLP based on student data collected by suggesting projects or educational resources, appropriate timelines, and teammates to work with. The instruction function is where learning takes place based on the PLP. Teachers can share information about projects and provide resources. Students can explore resources, create products, use computer-based instruction, and share resources with other students. The assessment function allows teachers to assess learning outcomes by testing different content, providing feedback, and certifying attainments (Fig. 2).

Adapted from Reigeluth et al. (2015)

Technology System for Personalized Learning.

The four functions are seamlessly integrated to effectively and efficiently support PL. Students’ data in the recordkeeping function feed into the planning function to prepare a PLP for individual students. Based on the plans, the students engage in a project with instructional support through an instructional overlay. In the instructional overlay, ongoing formative assessment takes place and the mastery data are added into the recordkeeping function. Thus, this study addresses which kinds of personalized learning practices and technology use are different between academically high-performing and low-performing learner-centered schools.

Methods

Research design

This study utilized a cross-sectional survey design and used survey responses from ELA (English and Language Arts) teachers in learner-centered schools in the U.S. and existing data on school performance measured by state standardized tests. After identifying learner-centered schools (see sample selection below), a survey was sent to the teachers to ask about their PL practice and technology use. Schools’ academic performance and profile data were collected from the National Center of Education Statistics or each state’s Department of Education.

In order to sample our data, we first identified learner-centered schools that had adopted PL and categorized them based on their level of academic performance to compare their PL practices and technology uses. To identify high-performing (high) and low-performing (low) schools, schools’ adequate yearly progress (AYP) in reading was used. Between math and reading of which AYP was available across different states, reading’s AYP was used because the number of survey responses of reading was large enough to conduct the statistical tests with sufficient statistical power.

Data collection

Sample selection

Learner-centered schools in the U.S. were identified through a literature and internet search of the 50 states’ Department of Education websites, and a list of the schools that one of the authors had gathered for two decades. Each school’s website was reviewed again to rate how many criteria of the five essential PL features were met by each. A total of 308 schools that met at least three of the five criteria were included because schools with fewer than three features would be hard to be considered as learner-centered schools, while setting the minimum number of criteria at four or five would severely restrict variability in PL practice within our sample. A total of 431 participants from 72 schools responded to the survey. Among them, 102 teachers from 17 schools reported that they taught ELA.

Development of survey instruments for PL practice and technology use

Survey instruments were developed based on the five essential criteria and the PIES framework. Validity of the survey was enhanced by: (1) determining constructs and operational definitions through our literature review to support construct validity, (2) developing survey instruments for the constructs using terms from schools’ websites to ensure using terminology commonly used in the schools, (4) conducting expert reviews with two experts on the learner-centered paradigm to support construct and content validities, (5) testing usability of interface and browser compatibility, and (6) conducting pilot tests of the survey using a think-aloud protocol with four subjects who possessed K-12 teaching experience in the U.S. and were familiar with learner-centered instruction to support construct validity and minimize measurement errors. By conducting a literature review, expert reviews, and think-aloud pilot tests, construct and content validities of the survey were improved and measurement errors were reduced (Groves et al. 2013).

Five constructs of PL essential features were measured: (1) PLP, (2) CBSP, (3) CRA, (4) PBL, and (5) MYM. Also, the four major functions of PIES were measured: Planning, Learning, Assessment, and Recordkeeping. Survey respondents were asked to base their answers on the academic year, 2011–2012. The constructs, operational definitions, survey instruments, and objectives are presented in "Appendix" section.

School academic performance data and other school profiles

Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) reported by each school was used as an indicator of schools’ academic performance. The AYP data tell us how many students in each grade level in the school met or exceeded the proficiency level in a certain subject area. For all schools that responded, the AYP data for the academic year 2011–2012 and school profile information were collected from the National Center of Education Statistics or corresponding state department of education websites.

Data Analysis

Survey responses of high and low-performing learner-centered schools were compared. To identify these two groups, all teacher responses were rank-ordered based on academic performance in the subject area, and the top 20% and bottom 20% of teachers were identified. The percentage was selected to ensure a large enough sample size for analysis and to make a clear distinction between the high and low-performing groups.

Among 102 ELA teachers’ responses, AYP data of 82 were retrieved, and 16 teacher responses were selected each for the high and low performing groups. The high performing group (M = 86.32, SD = 6.79) and the low performing group (M = 36.63, SD = 2.68) were significantly different in terms of school academic performance, p < 0.0001 as a result of an independent-samples t-test. The 16 teachers in the high performing group were from 9 schools and the 16 teachers in the low performing group were from 5 schools.

The two groups were compared in terms of their school profile, the five features, and technology use. School profiles included type of school (private, public, and charter), location (urban, rural, town, and suburban), student population (ethnicity and students who are eligible for free and reduced lunch (FRL)), number of students served, and student–teacher ratio. These profiles were identified through state education agency websites or the National Center for Education Statistic. Characteristics of student populations were included because of their plausible relationships with student academic achievement (Caldas and Bankston 1997; Han et al. 2014; Melendez 2013; Steinberg et al. 1992; Thomas and Collier 2002). These characteristics and survey responses were compared between the two groups using two statistical tests. The responses from the 5-point Likert-type scale were numerically coded from 1, no presence of the characteristic to 5, full presence. Responses of the question asking for the percentages were used as they were. Independent-samples t-tests were performed to compare the two groups on constructs measured as ordinal variables, such as responses from a Likert-type scale. Upon visual inspection of the data, there was no evidence of violating the normality assumption. Levene’s test for equality of variance was used to check the assumption of homogeneity of variance. When the assumption was not met, statistics for equal variances not assumed were reported. Chi-square tests were performed for categorical variables, including Yes/No responses. Table 1 summarizes the test used.

Results

School profile

Table 2 presents school type and locations of the schools in the high-performing and low-performing groups. There were five public charter schools in the high performing group and none in the low performing group. Regarding location, in the high group, there were six schools in cities, whereas in the low group there was one.

Table 3 presents total students served, student–teacher ratios, and FRL rates of the schools in the two groups. In terms of total students served, the school sizes of the high performing group were nearly half of the school sizes of the low performing group. However, there was not much difference in terms of student–teacher ratio. FRL rates were generally higher in the low performing group.

Personalized learning plan

There was a significant difference between the two groups in terms of considering career goals when creating PLPs. The high performing group considered career goals more frequently than the low performing group; t(32) = 3.09, p = 0.004. The high performing group often considered career goals (MFootnote 2 = 3.78, SDFootnote 3 = 1.22), whereas the low performing group rarely or sometimes took career goals into account (M = 2.44, SD = 1.31).

No significant differences were found in other factors at α = 0.05. However, the high performing group tended to consider more student interest (\(\Delta M=0.35)\)Footnote 4 and characteristics (\(\Delta M=0.12)\) than academic standards (\(\Delta M=-0.39)\) or student mastery (\(\Delta M=-0.17)\) compared to the low performing group. Also, the high performing group tended to more frequently implement the PLPs than the low performing group (\(\Delta M=0.32)\). These differences were small and non-significant though.

Competency-based student progress & criterion-referenced assessment

No significant differences were found for CBSP and CRA. There was no significant difference on CBSP between the high performing group (M = 4.21, SD = 1.48) and the low performing group (M = 4.46, SD = 0.88); t(25) = -0.524, p = 0.605. Both groups showed that students individually had progressed as soon as each student had mastered the current topic or each project team had progressed to the next topic when the team of students had mastered the current topic.

Also, a chi-square test for CRA revealed that there was no statistically significant association between the groups and assessment practice; χ2 (1) = 1.033, p = 0.310, meaning that there was no tendency toward a certain assessment practice, CRA or NRA, between the two groups. Another chi-square test for grade form resulted in no significant association between the groups and form of grade; χ2 (1) = 3.033, p = 0.082, meaning that there was no tendency toward traditional grades or individual mastery of skills as a form of student academic data between the two groups.

PBL

There was no statistically significant difference in terms of frequency of using PBL t(25) = 0.842, p = 0.408. Both groups often used PBL, although the high performing group used it slightly more frequently (M = 3.93, SD = 1.21) than the low performing group (M = 3.54, SD = 1.20).

Group size, duration, and nature of inquiry

While no statistically significant differences were found for group size, duration, nature of inquiry, and types of instructional support between the two groups, the high performing group tended to have longer duration of PBL than the low performing group, and more projects were performed individually. The high performing group reported that typical PBL projects lasted 2–3 weeks or about a month (M = 3.43, SD = 1.50), and the low performing group reported a little less than that (M = 2.75, SD = 1.14). In the high performing group, 16% more projects were performed individually (M = 55.71%, SD = 28.95) than in the low performing group (M = 39.58%, SD = 29.42).

In addition, no statistically significant difference was detected for the nature of PBL inquiry; however, the high performing group tended to use more real-world inquiries (fFootnote 5 = 10) than hypothetical inquiries compared to the low performing group (f = 5), as shown in Table 4. Also, the high performing group tended to use various instructional resources more frequently than the low performing group across all survey items, including teacher lecturing, teacher coaching, CBI, peer, and outside experts. Especially, the differences were bigger for teacher coaching (\(\Delta\) M = 0.75) and outside experts (\(\Delta\) M = 0.82).

Student activities

In terms of student activities during PBL, there was a statistically significant difference on frequency of sharing final products of PBL with the community. The high performing group shared their products with the community more frequently than the low performing group; t(24) = 2.677, p = 0.013. The high performing group sometimes shared their products (M = 2.79, SD = 1.37), whereas the low performing group never or rarely shared their products (M = 1.58, SD = 0.79). No significant differences were found in other activities. However, the high performing group consistently reported more frequent student activities throughout the related survey items. Especially, the differences were relatively large for presenting final products in class (\(\Delta\) M = 0.74), reflecting on what students had learned (\(\Delta\) M = 0.52), and self-monitoring student progress (\(\Delta\) M = 0.49).

PBL assessment

There were significantly more respondents in the high performing group that reported they assessed nonacademic performance on the project, such as effort, work ethics, time management, communication, or collaboration; χ2 (2) = 8.396, p = 0.015. Table 5 compares the high and low performing groups in terms of assessment of nonacademic performance. Other than this, there were no statistically significant or obvious differences between the two groups in terms of PBL assessment.

Multi-year mentoring

Statistically significant differences were found in: (1) number of years with the same students and (2) close relationship with students between the high and low performing groups. The teachers in the high performing group stayed for 2.5 years on average with the same cohort (SD = 1.45), while those in the low performing group stayed for 1.25 years (SD = 0.87); t(21) = 2.705, p = 0.013. Also, the teachers in the high performing group reported that they were able to build close relationships with about 75% to all students (M = 4.46, SD = 0.66), whereas those in the low performing group reported about 50% to 75% of students (M = 3.56, SD = 0.53); t(20) = 3.423, p = 0.003.

Technology use

There was a significant difference in number of functions integrated into the school’s technology system. The high performing group had 2.60 functions on average (SD = 0.97), whereas the low performing group had 1.83 functions (SD = 0.72); t(20) = 2.135, p = 0.045. Also, more students in the high performing group used technology in sharing resources with their peers than those in the low performing group; χ2 (1) = 5.057, p = 0.025. Throughout the four functions, generally, more teachers in the high performing group utilized technology than in the low performing group. Table 6 compares the two groups’ survey responses on the four technology functions: recordkeeping, planning, instruction, and assessment.

Implications, limitations, and future research

Our analysis revealed several interesting aspects of PL practice and technology use in K-12 learner-centered schools. Four guidelines for PL schools can be inferred.

First, PL schools should implement the five PL features thoroughly. High-performing schools generally implemented PL more thoroughly and practiced the five PL features more frequently than low-performing schools. This evidence supports that PL, if thoroughly designed and implemented, can be effective in enhancing academic achievement measured by standardized tests. More specifically, high-performing schools demonstrated effort to connect their practice to the real world by considering students’ career goals when creating personalized learning plans (PLPs), having students work on real-world inquiries, and including community in the process of learning. In high-performing schools, students shared their PBL artifacts with the community, affording students an opportunity to engage in dialogues with real world audiences and giving their school projects authentic purposes. Lee and Hannafin (2016) urged having authentic audiences for student-centered learning projects to enhance student engagement. LEAP Innovations (2020) provided strategies for creating real-world connections in PBL. Projects can be designed to involve community by collecting data from local people, providing civic or community services, or implementing a cross-school collaboration project. Furthermore, more well-rounded assessments were used in high-performing schools by focusing on both academic and non-academic outcomes. LEAP Innovations (2020) recommended assessing and providing feedback on effort, process, and mastery in an objective and non-judgmental way while encouraging students to experiment with multiple strategies to solve problems or accomplish projects.

Second, making personal connections between students and teacher can positively influence the outcome of PL practices. High-performing schools had longer multi-year mentoring (MYM) than low-performing schools. Feeling close to their teachers and respected for their personal interests and career plans can augment elementary students’ engagement with school and academic endeavors (Reevs 2006). For high-school students, having more positive interactions with the teacher predicted positive school engagement and academic life (Martin and Collie 2019). Connections between students and teachers can improve students’ sense of purpose in school and school performance. LEAP Innovations (2020) provides specific guidelines as to how to cultivate meaningful relationships, such as establishing a daily reflection shared between students, parents, and teachers; collaboratively developing a PLP with a student, parents, and teacher; and guiding and supporting students throughout the PBL process.

Third, it is essential for PL schools to utilize an integrated technology system and train teachers to support all four functions of recordkeeping, planning, learning, and assessment. High-performing schools were better equipped with a technology system that integrated all four functions, and teachers used technology in a wider variety of ways. A learning management technology system can benefit all members of a school, including teachers, students, administrators, and parents (Reigeluth et al. 2008). Data can provide evidence of student performances and year-to-year progress; therefore, teachers can give personal attention to individuals and adjust practices accordingly. Parents receive meaningful feedback on student performances and can work more easily with the student at home. These data can provide administrators with a base for confident decision making. Learning management systems that are available currently include Canvas, in which personalized learning paths can be created for individual learners, and Google Classroom, in which teachers can provide different learning materials to individual learners.

Finally, when putting these research results into practice, educators should keep in mind that a piecemeal change at the surface level would not be sufficient to bring the results of the high-performing schools—that PL should be implemented in its entirety with high fidelity. For example, incorporating career goals into PLP was one of the statistically significant differences between high and low-performing schools. However, if a traditional teacher-centric school decided to create PLPs for the students and include career goals as a component, this alone would not be sufficient to achieve the same result found in high-performing schools. The learner-centered schools surveyed practiced at least three of the PL features. So, creating a PLP with career goals should be accompanied by selecting projects based on their career goals that engage students in the projects with real-world connections, assessing various processes and outcomes, providing enough feedback to learners, and building meaningful relationships throughout the process.

This study was conducted when the U.S. K-12 system was under NCLB. Its findings hold value in that personalized, learner-centered approaches with high implementation fidelity can be effective, as measured by standardized tests, even in the midst of nationwide notorious testing requirements and penalties implemented. The study findings encourage educators to adopt PL and support the PL component of ESSA.

This study bears limitations on sample size and school data limited to the United States. Effects of PL on academic outcomes should continue to be investigated with a larger sample size as well as with student-level academic data and other related factors. Many non-significant results could be attributed to (1) the small sample size, (2) no significant effects at the teacher or school levels, or (3) insufficient variance in participant responses. It follows that results might be different if there were a large enough sample size or if the effects were examined at the student level, not the teacher or school levels. If teachers in both groups similarly practice a certain PL feature, it will not lead to a significant difference, but the PL feature may be highly valuable for student learning. Also, the small sample may limit the generalizability of the study findings. Also, this study was conducted with the schools in the United States, and the findings should not be generalized to other cultural contexts.

Given that PL is in its infancy, further research can concretize practices and inform scaling up PL. First, high-performing and low-performing schools should be closely observed using ethnographic approaches, and their practice and technology use should be extensively documented and compared. This type of multiple case study allows us to identify unknown factors that are directly or indirectly related to academic achievement and provide a richer description of high-performing schools in comparison to low-performing schools.

Second, the effects of PL on non-academic outcomes, such as critical thinking, creativity, collaboration, and social-emotional skills, should be also investigated. These learning outcomes are at least as important as academic achievement to student success. Also, PBL is known to have positive effects on these learning outcomes (Bell 2010; Han et al. 2014; Hmelo-Silver 2004).

Third, major technology needs were revealed, and the importance of an integrated educational technology system (i.e., PIES) that collects and stores students’ data, helps plan individualized lessons or projects, provides instructional support, and assesses students’ learning outcomes has been found in this study for ELA. Also, connected to such a technology system, mobile learning has shown great potential in corporate training to enable learning to be personalized and to take place anywhere and anytime, which is especially important in times of a global pandemic such as Covid-19. Therefore, research should be directed to identifying functional specifications and facilitating the development and implementation of such a system and mobile applications through design-based research.

Notes

Recently renamed the Aurora Institute.

M: Mean.

SD: Standard deviation.

\(\Delta M\): Difference in two means.

f: frequency.

References

American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force on Psychology in Education. (1993). Learner-Centered Psychological Principles: Guidelines for School Redesign and Reform. Washington, D. C.: American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force on Psychology in Education.

Bell, S. (2010). Project-based learning for the 21st century: Skills for the future. Clearing House, 83(2), 39–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098650903505415.

Bloom, B. S. (1984). The 2 sigma problem: The search for methods of group instruction as effective as one-to-one tutoring. Educational Researcher, 13(6), 4–16.

Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (2000). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School. Washington, D. C.: National Academies Press.

Caldas, S. J., & Bankston, C. (1997). Effect of school population socioeconomic status on individual academic achievement. The Journal of Educational Research, 90(5), 269–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.1997.10544583.

Carroll, J. B. (1963). A model of school learning. Teachers College Record, 64(8), 723–733.

Center on Education Policy. (2007). Answering the Question that Matters Most: Has Student Achievement Increased Since No Child Left Behind? http://www.cep-dc.org.

Department for Education and Skills. (2004). Department for Education And skills: Five Year Strategy for Children and Learners. (Cm 6272). England.

District Reform Support Network. (2016). Transforming the Culture of Teaching and Learning: Four Race to the Top-District Grantees' Implementation of Personalized Learning. Retrieved from https://rttd.grads360.org/#communities/pdc/documents/12121.

Duch, B. J., Groh, S. E., & Allen, D. E. (2001). Why problem-based learning? A case study of institutional change in undergraduate education. In B. J. Duch, S. E. Groh, & D. E. Allen (Eds.), The Power of Problem-Based Learning (pp. 3–11). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), (2015).

George, P. S., Spreul, M., & Moorefield, J. (1987). Long-Term Teacher-Student Relationships: A Middle School Case Study. Columbus, OH: National Middle School Association.

Gijbels, D., Dochy, F., Van den Bossche, P., & Segers, M. (2005). Effects of problem-based learning: A meta-analysis from the angle of assessment. Review of Educational Research, 75(1), 27–61. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543075001027.

Gross, B., Tuchman, S., & Patrick, S. (2018). A National Landscape Scan of Personalized Learning in k-12 Education in the United States. Retrieved from Vienna, Virginia.

Groves, R. M., Fowler, F. J., Jr., Couper, M. P., Lepkowski, J. M., Singer, E., & Tourangeau, R. (2013). Survey Methodology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Han, S., Capraro, R., & Capraro, M. M. (2014). How science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) project-based learning (PBL) affects high, middle, and low achievers differently: The impact of student factors on achievement. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-014-9526-0.

Hmelo-Silver, C. E. (2004). Problem-based learning: What and how do students learn? Educational Psychology Review, 16(3), 235–266.

Hursh, D. (2007). Assessing no child left behind and the rise of neoliberal education policies. American Educational Research Journal, 44(3), 493–518. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831207306764.

Jonassen, D. H. (2000). Toward a design theory of problem solving. Educational Technology Research and Development, 48(4), 63–85.

Jonassen, D. H. (2004). Learning to Solve Problems: An Instructional Design Guide. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

La Velle, L., & Flores, M. A. (2018). Perspectives on evidence-based knowledge for teachers: Acquisition, mobilisation and utilisation. Journal of Education for Teaching, 44(5), 524–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2018.1516345.

Lambert, N. M., & McCombs, B. L. (Eds.). (1998). How Students Learn: Reforming Schools Through Learner-Centered Education. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

LEAP Innovations. (2020). Leap Learning Framework for Personalized Learning: 2020 Edition. Retrieved from https://www.leapinnovations.org/leap-learning-framework/.

Lee, D. (2014). How to personalize learning in k-12 schools: Five essential design features. Educational Technology, 54(2), 12–17.

Lee, E., & Hannafin, M. J. (2016). A design framework for enhancing engagement in student-centered learning: Own it, learn it, and share it. Educational Technology Research and Development, 64(4), 707–734. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-015-9422-5.

Li, K. C., & Wong, B.T.-M. (2019). How learning has been personalised: A review of literature from 2009 to 2018. Blended Learning: Educational Innovation for Personalized Learning (pp. 72–81). Hradec Kralove: Springer International Publishing.

Lin, C. F., Yeh, Y., Hung, Y. H., & Chang, R. I. (2013). Data mining for providing a personalized learning path in creativity: An application of decision trees. Computers & Education, 68, 199–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.05.009.

Ma, M., Fallavollita, P., Seelbach, I., Von Der Heide, A. M., Euler, E., Waschke, J., & Navab, N. (2016). Personalized augmented reality for anatomy education. Clinical Anatomy, 29(4), 446–453. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.22675.

Martin, A. J., & Collie, R. J. (2019). Teacher–student relationships and students’ engagement in high school: Does the number of negative and positive relationships with teachers matter? Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(5), 861–876. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000317.

Maseleno, A., Sabani, N., Huda, M., Ahmad, R., Jasmi, K. A., & Basiron, B. (2018). Demystifying learning analytics in personalised learning. International Journal of Engineering & Technology, 7(3), 1124–1129. https://doi.org/10.14419/ijet.v7i3.9789.

McCombs, B. L. (2008). From one-size-fits-all to personalized learner-centered learning: The evidence. The FM Duffy Reports, 13(2), 1–12.

McCombs, B. L. (2013). The learner-centered model: Implications for research approaches. In J. H. D. Cornelius-White, R. Motschnig-Pitrik, & M. Lux (Eds.), Interdisciplinary Handbook of the Person-Centered Approach (pp. 335–352). New York: Springer.

Melendez, R. L. (2013). Exploring the Academic Achievement Gap Among Hispanic Students on State Standardized Tests. (Doctoral dissertation), University of Phoenix, Retrieved from http://gradworks.umi.com/35/78/3578026.html.

Miliband, D. (2006). Choice and voice in personalised learning. In OECD (Ed.), Schooling for Tomorrow Personalising Education (pp. 21–30). New York: OECD Publishing.

No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, (2001).

Patrick, S., Worthen, M., Frost, D., & Gentz, S. (2016a). Meeting the Every Student Succeeds Act's Promise: State Policy to Support Personalized Learning. iNACOL.

Patrick, S., Worthen, M., Frost, D., & Gentz, S. (2016b). Promising State Policies for Personalized Learning. Retrieved from Vienna, VA.

Reevs, J. (2006). Teachers as facilitators: What autonomy-supportive teachers do and why their students benefit. The Elementary School Journal, 106(3), 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1086/501484.

Reigeluth, C. M., Aslan, S., Chen, Z., Dutta, P., Huh, Y., Lee, D., & Tan, V. (2015). Personalized integrated educational system technology functions for the learner-centered paradigm of education. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 53(3), 459–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633115603998.

Reigeluth, C. M., & Karnopp, J. R. (2013). Reinventing Schools: It’s Time to Break the Mold. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Reigeluth, C. M., Watson, W. R., Watson, S. L., Dutta, P., Chen, Z., & Powell, N. D. P. (2008). Roles for technology in the information-age paradigm of education: Learning management systems. Educational Technology, 48(6), 32–39.

Savery, J. R. (2006). Overview of problem-based learning: Definitions and distinction. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-based Learning, 1(1), 9–20.

Sebba, J., & Britain, G. (2007). An Investigation of Personalised Learning Approaches Used by Schools. England: DfES Publications.

Şendağ, S., & Ferhan Odabaşı, H. (2009). Effects of an online problem based learning course on content knowledge acquisition and critical thinking skills. Computers & Education, 53(1), 132–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.01.008.

Smith, J. M., & Kovacs, P. E. (2011). The impact of standards-based reform on teachers: The case of ‘no child left behind.’ Teachers and Teaching, 17(2), 201–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2011.539802.

Software & Information Industry Association. (2010). Innovate to educate: System [re]design for personalized learning; a report from the 2010 symposium. In M. A. Wolf (Ed.), Collaboration with ascd and the council of chief state school officers. Washington, DC: Software & Information Industry Association.

Steinberg, L., Dornbusch, S. M., & Brown, B. B. (1992). Ethnic differences in adolescent achievement: An ecological perspective. American Psychologist, 47(6), 723. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.47.6.723.

Sturgis, C., & Patrick, S. (2010). When Success is the Only Option: Designing Competency-Based Pathways for Next Generation Learning. Retrieved from Quincy, MA.

Thomas, W. P., & Collier, V. P. (2002). A National Study of School Effectiveness for Language Minority Students' Long-Term Academic Achievement. Santa Cruz, CA: Center for Research on Education, Diversity and Excellence, Retrieved from http://www.crede.ucsc.edu/research/llaa/1.1_final.html.

Thorndike, R. M., & Thorndike-Christ, T. (2010). Measurement and Evaluation in Psychology and Education (8th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

U.S. Department of Education. (2010). Transforming American Education: Learning Powered by Technology. Washington, D. C.: Office of Educational Technology.

U.S. Department of Education. (2012a). Race to the Top District. Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/programs/racetothetop-district/index.html.

U.S. Department of Education. (2012b). Schools, Districts, and States Transform Seat-Based Requirements into Competency-Based Pathways to College- and Career-Readiness. Retrieved from http://www.ed.gov/oii-news/schools-districts-and-states-transform-seat-based-requirements-competency-based-pathways-co.

U.S. Department of Education. (2017). Reimagining the Role of Technology in Education. Office of Educational Technology Retrieved from https://tech.ed.gov/files/2017/01/NETP17.pdf.

U.S. Department of Education. (n.d.). Competency-Based Learning or Personalized Learning. Retrieved from http://www.ed.gov/oii-news/competency-based-learning-or-personalized-learning.

Underwood, J., Baguley, T., Banyard, P., Coyne, E., Farrington-Flint, L., & Selwood, I. (2007). Impact 2007: Personalising Learning with Technology. Coventry, England: British Educational Communications and Technology Agency.

WestEd. (2006). Charter High Schools: Closing the Achievement Gap. Retrieved from http://www.ed.gov/admins/comm/choice/charterhs/index.html.

Wirkala, C., & Kuhn, D. (2011). Problem-based learning in k–12 education is it effective and how does it achieve its effects? American Educational Research Journal, 48(5), 1157–1186. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831211419491.

Funding

There was no funding received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no co nflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Constructs, operational definitions, corresponding survey instruments and objectives

Appendix: Constructs, operational definitions, corresponding survey instruments and objectives

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, D., Huh, Y., Lin, CY. et al. Differences in personalized learning practice and technology use in high- and low-performing learner-centered schools in the United States. Education Tech Research Dev 69, 1221–1245 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-021-09937-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-021-09937-y