Abstract

Background

Smartphones offer the possibility of assessing recovery of mobility after total hip or knee arthroplasty (THA or TKA) passively and reliably, as well as facilitating the collection of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) with greater frequency.

Questions/Purposes

We investigated the feasibility of using mobile technology to collect daily step data and biweekly PROMs to track recovery after total joint arthroplasty.

Methods

Pre- and post-operative daily steps were recorded in prospectively enrolled patients (128 THA and 139 TKA) via an app, which uses the phone’s accelerometer. During 6-month follow-up, patients also completed PROMs (the pain numeric rating scale, the Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Joint Replacement [HOOS JR] and the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Joint Replacement [KOOS JR]), and HOOS or KOOS JR quality of life domain via a mobile-enabled web link.

Results

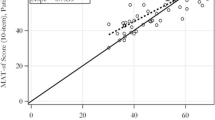

At least 6 months of follow-up was completed by 65% for THA and 68% for TKA patients. Reasons for non-completion included time commitment, phone battery, app issues, and health complications. Responses from 78% of requested PROMs were returned with 96% of patients returning at least one post-operative PROM. Step data were available from 92% of days from male patients and 86% of days from female patients. The most robust recovery occurred early, within the first 2 months. The groups with higher pre-operative steps were more likely to recover their maximum daily steps at an earlier time point. Correlations between step counts and PROMs scores were modest.

Conclusion

Assessing large amounts of post-TKA and post-THA step data using mobile technology is feasible. Completion rates were good, making the technology very useful for collecting frequent PROMs. Being unable to ensure that patients always carried their phones limited our analysis of the step counts.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Arnold JB, Walters JL, Ferrar KE. Does physical activity increase after total hip or knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis? A systematic review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2016;46:1–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2016.6449.

Bellamy N, Wilson C, Hendrikz J, et al. Osteoarthritis Index delivered by mobile phone (m-WOMAC) is valid, reliable, and responsive. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:182–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.013.

Bourne RB, Chesworth B, Davis A, Mahomed N, Charron K. Comparing patient outcomes after THA and TKA: Is there a difference? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:542–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-009-1046-9.

Case MA, Burwick HA, Volpp KG, Patel MS. Accuracy of smartphone applications and wearable devices for tracking physical activity data. JAMA. 2015;313:625. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.17841.

Collins M, Lavigne M, Girard J, Vendittoli P. Joint perception after hip or knee replacement surgery. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98:275–280. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsr.2011.08.021.

De Groot IB, Bussmann HJ, Stam HJ, Verhaar JA. Small increase of actual physical activity 6 months after total hip or knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:2201–2208. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-008-0315-3.

Dehling T, Gao F, Schneider S, Sunyaey A. Exploring the far side of mobile health: information security and privacy of mobile health apps on iOS and Android. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3(1):e8.

Dobkin BH, Dorsch A. Assessments by wearable sensors. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2014;25:788–798. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968311425908.

Freburger JK, Holmes GM, Ku L-JE, Cutchin MP, Heatwole-Shank K, Edwards LJ. Disparities in post-acute rehabilitation care for joint replacement. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63:1020–1030. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20477.

Fujita K, Makimoto K, Tanaka R, Mawatari M. Prospective study of physical activity and quality of life in Japanese women undergoing total. Epidemiology. 1997;50:239–46.

Harding P, Holland AE, Delany C, Hinman RS. Do activity levels increase after total hip and knee arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(5):1502–1511. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-013-3427-3.

Hayes DA, Watts MC, Anderson LJ, Walsh WR. Knee arthroplasty: A cross-sectional study assessing energy expenditure and activity. ANZ J Surg. 2011;81:371–374. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05570.x.

Kennedy DM, Stratford PW, Riddle DL, Hanna SE, Gollish JD. Assessing recovery and establishing prognosis following total knee arthroplasty. Phys Ther. 2008;88:22–32.

Kennedy DM, Stratford PW, Wessel J, Gollish JD, Penney D. Assessing stability and change of four performance measures: a longitudinal study evaluating outcome following total hip and knee arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2005;6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-6-3.

Kim K, Pham D, Schwarzkopf R. Mobile application use in monitoring patient adherence to perioperative total knee arthroplasty protocols. Surg Technol Int. 2016;28:253–260.

Kingsbury SR, Dube B, Thomas CM, Conaghan PG, Stone MH. Is a questionnaire and radiograph-based follow-up model for patients with primary hip and knee arthroplasty a viable alternative to traditional regular outpatient follow-up clinic? Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B:201–208. doi:https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.98B2.36424.

Kinkel S, Wollmerstedt N, Kleinhans JA, Hendrich C, Heisel C. Patient activity after total hip arthroplasty declines with advancing age. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:2053–2058. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-009-0756-3.

Koutras C, Bitsaki M, Koutras G, Nikolaou C, Heep H. Socioeconomic impact of e-Health services in major joint replacement: A scoping review. Technol Health Care. 2015;23:809–817. doi:https://doi.org/10.3233/THC-151036.

Lingard EA, Berven S, Katz JN. Management and care of patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: variations across different health care settings. Arthritis Care Res 2000;13:129–36.

Lützner C, Kirschner S, Lützner J. Patient activity after TKA depends on patient-specific parameters. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(12):3933–3940.

Lyman S, Lee Y-Y, Franklin PD, Li W, Cross MB, Padgett DE. Validation of the KOOS, JR: a short-form knee arthroplasty outcomes survey. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1461–1471. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-016-4719-1.

Lyman S, Lee YY, Franklin PD, Li W, Mayman DJ, Padgett DE. Validation of the HOOS, JR: a short-form hip replacement survey. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1472–1482. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-016-4718-2.

Mehta N, Steiner C, Fields KG, Nawabi DH, Lyman SL. Using mobile tracking technology to visualize the trajectory of recovery after hip arthroscopy: a case report. HSS J. 2017;13:194–200. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11420-017-9544-x.

Naal FD, Impellizzeri FM. How active are patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty? A systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:1891–1904. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-009-1135-9.

National Institutes of Health. NIH-Wide Strategic Plan Fiscal Years 2016–2020. Available at: https://www.nih.gov/sites/default/files/about-nih/strategic-plan-fy2016-2020-508.pdf. Accessed April 3, 2017.

Naylor J, Harmer A, Fransen M, Crosbie J, Innes L. Status of physiotherapy rehabilitation after total knee replacement in Australia. Physiother Res Int. 2006;11:35–47.

Neuprez A, Delcour J-P, Fatemi F, et al. Patients’ expectations impact their satisfaction following total hip or knee arthroplasty. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0167911. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167911.

O’Brien S, Bennett D, Doran E, Beverland DE. Comparison of hip and knee arthroplasty outcomes at early and intermediate follow-up. Orthopedics. 2009;32:168.

Pew Research Center, Internet and Technology. Demographics of mobile device ownership and adoption in the United States. Mobile fact sheet. 2019. Washington, DC. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/

Rao PJ, Phan K, Maharaj MM, Pelletier MH, Walsh WR, Mobbs RJ. Accelerometers for objective evaluation of physical activity following spine surgery. J Clin Neurosci. 2016;26:14–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2015.05.064.

Ramkumar PN, Muschler GF, Spindler KP, Harris JD, McCulloch PC, Mont MA. Open mHealth architecture: a primer for tomorrow’s orthopedic surgeon and introduction to its use in lower extremity arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:1058–1062. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2016.11.019.

Robertson NB, Battenberg AK, Kertzner M, Schmalzried TP. Defining high activity in arthroplasty patients. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B:95–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.98B1.36438.

Roos EM. Effectiveness and practice variation of rehabilitation after joint replacement. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2003;15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00002281-200303000-00014.

Saleh KJ, Mulhall KJ, Bershadsky B, et al. Development and validation of a lower-extremity activity scale. Use for patients treated with revision total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1985–1994. doi:https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.D.02564.

Schmalzried TP, Szuszczewicz ES, Northfield MR, et al. Quantitative assessment of walking activity after total hip or knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:54–59.

Semple JL, Sharpe S, Murnaghan ML, Theodoropoulos J, Metcalfe KA. Using a mobile app for monitoring postoperative quality of recovery of patients at home: a feasibility study. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2015;3:e18. doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.3929.

Stratford PW, Kennedy DM, Maly MR, MacIntyre NJ. Quantifying self-report measures’ overestimation of mobility scores postarthroplasty. Phys Ther. 2010;90:1288–1296.

Takenaga RK, Callaghan JJ, Bedard NA, Liu SS, Gao Y. Which functional assessments predict long-term wear after total hip arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:2586–2594. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-013-2968-9.

Toogood PA, Abdel MP, Spear JA, Cook SM, Cook DJ, Taunton MJ. The monitoring of activity at home after total hip arthroplasty. Bone Jt J. 2016;98-B:1450–1454. doi:https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.98B11.BJJ-2016-0194.R1.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Caroline Boyle, Isabel Wolfe, and Naomi Roselaar for their assistance in preparing this manuscript.

Funding

Stephen Lyman, PhD, was supported in part by funds from Weill Cornell Medicine, Grant No. 5UL1TR000457.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Chisa Hidaka, MD, Kara Fields, MS, and Wasif Islam, BS, declare that they have no conflicts of interest. Stephen Lyman, PhD, reports personal fees from Omni, Inc., JOSKAS, and Universal Research Solutions; editorial board membership at JBJS Statistics, outside the submitted work; and support for the current work in part by funds from the Clinical Translational Science Center (CTSC), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) grant #5UL1TR000457. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding source NCATS, based in Rockville, MD. David Mayman, MD, discloses personal fees from Smith and Nephew, OrthAlign, and Imagen, outside the submitted work.

Human/Animal Rights

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in this study.

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

Additional information

Level of Evidence: Level II: Prospective cohort study (therapeutic).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lyman, S., Hidaka, C., Fields, K. et al. Monitoring Patient Recovery After THA or TKA Using Mobile Technology. HSS Jrnl 16 (Suppl 2), 358–365 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11420-019-09746-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11420-019-09746-3