Abstract

Hypertension is a key risk factor for stroke, cardiovascular disease and dementia. Although the link between weight, sodium and hypertension is established in younger people, little is known about their inter-relationship in people beyond 80 years of age. Associations between blood pressure, anthropometric indices and sodium were investigated in 495 apparently healthy, community-living participants (age 90, SD 4.8; range 80–106), from the cross-sectional Belfast Elderly Longitudinal Free-living Aging STudy (BELFAST) study. In age-sex-adjusted logistic regression models, blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg significantly associated with body mass index (BMI) [odds ratio (OR) = 1.28/ kg/m2], with weight (OR = 1.22/kg) approaching significance (P = 0.07). In further age-sex-adjusted models, blood pressure above the 120/80 mmHg normotensive reference value significantly associated with BMI (OR = 1.44/kg/m2), weight (OR = 1.36/kg), skin-fold-thickness (OR = 1.33/mm) and serum sodium (OR = 1.37 mmol/l). In BELFAST participants over 80 years old, blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg is associated with BMI, in apparently similar ways to younger groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Current demographic trends show that those over 80 years of age are the fastest growing sector in populations across the industrialised world. In Europe, octogenarians will increase five-fold and centenarians eight-fold by 2050 (World Population Prospects 2002). The prevalence of hypertension—a major risk factor for stroke, cardiovascular disease and dementia—increases with age. Hypertension associates with disability (Hajjar et al. 2007) and reduces healthy life expectancy in ageing populations.

The recently published Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET) study shows that lowering blood pressure in people aged 80 and over, cuts total mortality by approximately 20%, stroke rate by 30%, stroke mortality by 40%, and reduces death rate from cardiovascular events by up to 23% (Beckett et al. 2008). In younger people, hypertension shows a clear link between obesity and salt measures. However, relatively little is known about the inter-relationship of these factors in the ‘oldest old’, though some supporting information relating blood pressure and weight control to good quality outcomes in nonagenarian men is described in the follow-up of the Physicians Health Study (Yates et al. 2008).

In this study, we evaluated the inter-relationship between blood pressure, anthropometric measures and sodium, amongst very elderly male and female, free-living people in the Belfast Elderly Longitudinal Free-living Ageing STudy (BELFAST) (Rea et al. 2000), and findings suggest that there are associations between blood pressure in the hypertensive range and measures of weight in the over 80s.

Methods

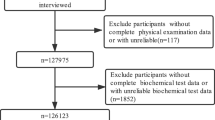

Subjects

The participants (Caucasian elderly subjects; 346 women and 149 men) included in the current report were aged 80 years or older, had blood pressure measurements available and were drawn from a longitudinal study of ageing—the Belfast Elderly Longitudinal Free-living Ageing STudy (BELFAST)—previously described by Rea et al. (2000). Briefly, when recruited, BELFAST octo/nonagenarians were community-living, apparently well, independently mobile, mentally competent (Folstein score > 25/30 with 30 being highest score; Folstein et al. 1995), and gave written consent. Ethical permission was given by The Queen’s University of Belfast Ethics Committee.

Measurements

A trained research nurse (A.M.) saw all the subjects at home on at least two visits, took medical history, anthropometric measurements and blood samples, as previously described (Rea et al. 1997). Height measurements were not included for subjects recruited early into the study, nor for subjects with severe kyphosis, where it was impossible for the research nurse to make a convenient or reliable measurement, thus BMI was not available for the total group. Waist and hip circumference were measured, in centimetres, at the narrowest point between ribs/hips and the widest diameter across the hips, respectively, for a lesser number of subjects.

Blood pressure was measured in the right arm, with the participant sitting, using a random-zero sphygmomanometer with regular cuff, after a 5-min rest period and using Kortakoff phase 1 and 5 sounds (Wright and Dore 1970). Serum sodium, and fasting lipid measurements were measured at Belfast City Hospital Laboratory, within 2 h of collection. The 24-h dietary recall for a subset of 96 subjects was analysed by CompEat Data Analysis (CompEat nutritional analysis program, Lifeline Nutritional Services, London). Dietary sodium was corrected for calorie intake.

As noted in Table 1, not all subjects completed all aspects of medical history, anthropometric measurements, blood sampling or dietary history because of competing interests, change of mind, family or personal concerns about subject fatigue or the protocol being burdensome.

Statistical analysis

The sex-specific characteristics and variables used in this dataset of 80- and 90-year-olds from the BELFAST study are described in Table 1. Mean values for anthropometric indices and sodium were compared between genders using a large-sample z test and between incremental thirds of systolic (<120 mmHg, 120–139 mmHg and ≥140/90 mmHg) and diastolic (<80 mmHg, 80–89 mmHg and ≥90 mmHg) blood pressure, using an analysis of variance test for trend. Unadjusted and age- and sex-adjusted logistic regression models considered anthropometric indices and serum sodium as predictors of hypertension (defined using a blood pressure cut-off of ≥140/90 mmHg) Models 1 and 2, or using 120/80 mmHg (defined as normotensive) as a comparator with hypertensive subject in Models 3 and 4. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Version 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL), with P values < 0.05 considered significant. The variables age, weight, BMI, waist-to-hip ratio, skin fold thickness (SFT) and serum sodium were standardised by dividing by the respective standard deviation for comparison of association/s with blood pressure. The units in the logistic regression models (except for sex) represent an increase in one standard deviation of the respective variable.

Results

Subject characteristics

Table 1 shows the sex-specific characteristics for the variables for 346 female and 149 male elderly participants. The mean (±SD) age was 90 (±4.8) years with systolic and diastolic blood pressures 137 (±21) mmHg and 85 (±14) mmHg, respectively. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure showed no sex-related change and subjects were analysed together.

Anthropometric variables, serum sodium, smoking and incremental thirds of blood pressure

Table 2 shows cross tabulation between incremental thirds of systolic (<120, 120–139 and ≥140/90 mmHg) and diastolic (<80, 80–89, ≥90 mmHg) blood pressure, the various anthropometric indices and serum sodium. Skin fold thickness and serum sodium level positively associated across incremental thirds of systolic blood pressure (P for trend = 0.01, P = 0.002 respectively), and weight (P = 0.08), waist (P = 0.08), waist-hip-ratio WHR (P = 0.07) approached significance though the effect for BMI (P = 0.16) was not so clear. Weight was associated with incremental increases in diastolic blood pressure (P = 0.05) with BMI not reaching significance (P = 0.10).

The percentage of subjects known to smoke was 16/123 (13.1%), 48/261(18.4%) and 29/181(16.0%), respectively, with no difference across incremental thirds of blood pressure (data not shown).

Medication use

There was a non significant increase in use of cardiovascular medication across the incremental thirds of blood pressure, with 38/123(30.8%), 91/261(34.8%), and 69/181(38.1%) of subjects taking any/or combinations of anti-hypertensive, diuretic or digoxin therapy (data not shown). The most commonly prescribed drug group was a diuretic with 23/123 (18.7%), 54/261(20.7%) and 37/181(20.4%) taking thiazide or a related diuretic (non significant) with digoxin use in 12/123 (9.7%), 25/261(9.6%) and 14/181(7.7%) subjects, across thirds of blood pressure, respectively. At the time of recruitment, anti-hypertensive use in this age group was uncommon, but if used, the most commonly prescribed anti-hypertensive used was of the β-blocker group.

Logistic regression models

Logistic regression models comparing subjects with and without hypertensive blood pressure (≥140/90 mmHg) and with reference blood pressure (≤120/80 mmHg), for anthropometric variables and serum sodium were constructed. Table 3 shows the unadjusted odds ratios (OR) comparing subjects >80 years of age in the hypertensive range (≥140/90 mmHg), with those below <140/90 mmHg, for an increase of 1 standard deviation in anthropometric and serum sodium variables (Model 1), and after adjusting for age and sex (Model 2). In the age and sex-adjusted model 2, the OR for blood pressure being in the hypertensive range compared to <140/90 mmHg was significant for BMI (OR = 1.28), with weight (OR = 1.22) approaching significance (P = 0.07).

Models 3 and 4 compared subjects with blood pressure >120/80 mmHg with those with normal reference blood pressure (≤120/80 mmHg). Model 4 (adjusted for age and sex) showed significant age-sex-adjusted ORs for weight (OR 1.36), BMI (OR 1.44), SFT (OR 1.33) and serum sodium (OR 1.37), with WHR (OR 1.39) approaching significance (P = 0.07). In a multiple logistic regression model comparing subjects categorised for blood pressure above and below 120/80 mmHg, both BMI (P = 0.02) and serum sodium (P = 0.01) were independent predictors of subjects with blood pressure above 120/80 mmHg for the BELFAST group (data not shown).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported study to demonstrate an association between some anthropometric measures (sodium and blood pressure) in a group of community-living subjects as old as 90 years of age, this being a somewhat surprising finding. BMI and, to a lesser extent, weight, were associated with blood pressure in the hypertensive range for BELFAST octo/nonagenarians. In this study, a 5 unit increase in BMI (BMI = 29) increased the chance of co-existing hypertension by about 30%.

Debate continues as to which anthropometric markers track best with cardiovascular risk and/or outcomes and whether they are applicable in very elderly people (Molarius et al. 2000), where changes in body composition (Harris et al. 2000) and osteoporosis make interpretation of anthropometry more challenging (Seidell and Visscher 2000). BMI is a less good measure of body composition in older women, where osteoporosis significantly reduces height and increases BMI measures inappropriately, especially in the ‘oldest old’ (Rea et al. 1997). In the BELFAST study, it was noteworthy that, although increases in weight significantly associated across the tertiles of blood pressure, the trend for BMI did not achieve significance. This may relate to differences in statistical power, since BMI values were not available for the entire cohort, or to the disproportionate influence of BMI with age in the larger group of women since, although both weight and BMI were important predictors of hypertension in the multivariate logistic model, the effect of BMI was much stronger after adjustment for age and sex.

The findings in the BELFAST ‘oldest old’ are similar to results in middle-aged people that link weight and/or anthropometric markers with hypertension (Siani et al. 2002, Chaudrey et al. 2004). In animals, evidence links obesity with altered blood pressure-natiuresis and increased salt sensitivity. In parallel studies in man, central adiposity relates to increased proximal sodium reabsorption (Rocchini et al. 1989) and altered renal handling is described in adipose men (Strazzullo et al. 2001).

Since sodium handling is altered in hypertensive people, and older people may be particularly sensitive to dietary salt (Whelton et al. 1998; Weinberger and Fineberg 1991), we looked for any association between dietary sodium intake in BELFAST subjects, as assessed by a single 24 h dietary recall, and blood pressure but found none; there are similar inconsistent findings for younger groups (Alderman et al. 1998). Additional limiting factors are lack of power due to small sample size and potential error using dietary recall methods. Only a very small number of the BELFAST subject group took medications of any kind, and there was no difference in diuretic and/or anti-hypertensive use across the incremental thirds of blood pressure that would readily explain the changes in serum sodium noted. Despite these constraints, at approximately 2 g daily, dietary sodium for the BELFAST ‘oldest old’ was low in comparison to population averages of between 4 and 7 g daily. Dietary sodium reduction can help reduce blood pressure by up to 3–5 mmHg across populations (Feng and McGregor 2002). In an important paper elucidating the underlying mechanisms, Gates et al. (2004) showed that dietary sodium reduction rapidly improved large elastic vessel compliance in older people with hypertension. The recent HYVET study (Beckett et al. 2008) noted the usefulness of diuretics in the very old population, and the current study also showed an approximate diuretic use of about 20%, suggesting possible mechanistic links between sodium homeostasis and blood pressure.

This study has a number of limitations. Blood pressure was measured only once by Hawksley random-zero sphygmomanometer, which may give lower estimates of blood pressure (Brown et al. 1997) compared with the less favored mercury sphygmomanometer. Only about 30% of the ‘oldest old’ in the BELFAST cohort were in the upper incremental third of the systolic and diastolic blood pressure consistent with hypertension, compared with 60% of older populations elsewhere (Chaudrey et al. 2004), and this may reflect a recruitment strategy that selected an ‘elite’ rather than an ‘all comer’ octo/nonagenarian cohort (Rea et al. 2000). Differing subject numbers and variables measured—a real issue for research participants and their relatives in this challenging age group (Samuelson et al. 2008)—may also have reduced the overall statistical power, particularly for male subjects.

This study finds that hypertension is associated with BMI and weight in 80- and 90-year-olds, in apparently similar ways to middle-aged people. Although in this cross-sectional study, the statistical associations between hypertension and BMI cannot be assumed to be causal, the size and direction of the associations are comparable to those noted in middle-aged groups. The findings could suggest that appropriate weight control throughout life should make hypertension less common in very old age, and that reduced salt intake may help. However, overweight 90-year-olds are likely to have other priorities for survival, and weight loss is unlikely to be one of them. In any case, traditional medical practice would hesitate to recommend that very elderly people lose weight (Seidell and Visscher 2000), but rather the opposite.

These findings challenge our thinking about what mechanisms might underpin blood pressure control in older people. Are they the same as in younger people or do 90-year-olds, by virtue of their survival, handle blood pressure and weight control differently? The ‘oldest old’ may be a highly exceptional group of people with a unique phenotype (Franceschi et al. 2007) who tolerate hypertension and survive higher BMI and weight better than the rest of us (Byers 2006). If this is so, do the complex gene/environment interactions of hypertension become changed with age, so that the genetic component (‘nature’) becomes more important than the environmental (‘nurture’) aspect, in a sort of antagonistic pleiotropy (Williams 1957). However, arguing against this suggestion are the findings that (1) in early follow-up of BELFAST nonagenarians, death occurred earlier where any vascular-related disease was noted on the death certificate and quality of life seemed reduced (Shields et al. 2002); (2) hypertension trebled the likelihood of stroke in Japanese centenarians (Arakawa et al. 2005); and (3) good blood pressure control reduced morbidity/mortality in the HYVET study (Beckett et al. 2008), and accompanied good quality ageing in the Physicians Health Study (Yates et al. 2008).

The findings in the BELFAST study need to be replicated by other groups. Although research studies of 90-year-olds are scare, as well as being challenging because of subject frailty, perceived vulnerability or lack of autonomy (Samuelson et al. 2008), they are highly important. Other cohorts of ‘oldest old’ such as the Framingham Study (Kannel et al. 2008) and the European Genetics of Healthy Ageing (GEHA) project (Franceschi et al. 2007) with increased statistical power are emerging, and outputs from these are needed to build up a base of scientific knowledge.

Understanding better the mechanisms underpinning blood pressure, even at advanced age, is important to people and societies. Stroke, the most tragic consequence of untreated hypertension (Kannel et al. 2008), increases with age and robs people of their mental and physical autonomy. Carrying out longitudinal follow-up studies on these interesting ‘old old’ populations, and using a combination of lifestyle and genetic factors in a multi-level analysis could help guide our understanding of the inter-relationship between hypertension and weight, and help guide optimal management strategies to exploit the ‘longevity dividend’ (Butler et al. 2008) for everyone.

References

Alderman MH, Cohen H, Madhavan S (1998) Dietary sodium intake and mortality: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES 1). Lancet 351:781–785. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)09092-2

Arakawa M, Miyake Y, Taira K (2005) Hypertension and stroke in centenarians, Okinawa, Japan. Cerebrovasc Dis 20:233–238. doi:10.1159/000087704

Beckett NS, Peters MB, Fletcher R, Staessen AE, Liu LJA, Dumitrascu D, for the HYVET Study Group et al (2008) Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age and older. New Engl J Med 358:1887–1898

Brown WC, Kennedy S, Inglis GC, Murray LS, Lever AF (1997) Mechanisms by which the Hawksley random zero sphygmomanometer underestimates blood pressure and produces a non-random distribution of RZ values. J Hum Hypertens 11:75–93. doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1000405

Butler RN, Miller RA, Perry D, Carnes BA, Williams TF, Cassel C et al (2008) New model of health promotion and disease prevention for the 21st century. BMJ 337:149–150

Byers T (2006) Overweight and mortality among baby boomers—now we are getting personal. N Engl J Med 355:758–760. doi:10.1056/NEJMp068156

Chaudrey SI, Krumholz HM, Foody JM (2004) Systolic hypertension in older persons. JAMA 292:1074–1080

Feng JH, McGregor GA (2002) Effect of modest salt reduction on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Implications for public health. J Hum Hypertens 16:761–770. doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1001459

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1995) Mini mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12:189–198. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

Franceschi C, Bezrukov V, Blanché H, Bolund L, Christensen K, De Benedictis G et al (2007) Genetics of healthy aging in Europe. The EU-Integrated Project GEHA (GEnetics of Healthy Aging). Ann N Y Acad Sci 1100:21–45. doi:10.1196/annals.139

Gates PE, Tanaka H, Hiatt WR, Seals DR (2004) Dietary sodium restriction rapidly improves large elastic artery compliance in older adults with systolic hypertension. Hypertension 44:35–41. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000132767.74476.64

Hajjar H, Lackland DT, Cupples A, Lipsitz LA (2007) Association between concurrent and remote blood pressure and disability in older adults. Hypertension 50:1026–1032. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.097667

Harris TB, Visser M, Everhart J, Cauley J, Tylavsky F, Fuerst T et al (2000) Waist circumference and sagittal diameter reflect total body better than visceral fat in older men and women. The Health Ageing and Body composition study. Ann N Y Acad Sci 904:462–473

Kannel WB, Wolf PA, Verter J, McNamara PM (2008) Framingham study insights on the hazards of elevated blood pressure. JAMA 300:2545–2547

Molarius A, Seidell JC, Visscher TL, Hofman A (2000) Misclassification of high-risk older subjects using waist action levels established for young and middle-aged adults—results from the Rotterdam Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 12:1638–1645

Rea IM, Gillen S, Clarke E (1997) Anthropometric measurements from a cross-sectional survey of community-living subjects >90 years of age. Eur J Clin Nutr 51:102–106. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600370

Rea IM, McMaster D, Woodside JV, Young IS, Archbold GP, Linton T et al (2000) Community-living nonagenarians in Northern Ireland have lower plasma homocysteine but similar methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase thermolabile genotype prevalence compared to 70–89 year olds. Atherosclerosis 149:207–214. doi:10.1016/S0021-9150(99)00417-7

Rocchini AP, Key J, Bondie D, Chico R, Moorehead C, Katch V et al (1989) The effect of weight loss on the sensitivity of blood pressure to sodium in obese adolescents. N Engl J Med 321:580–585

Samuelson EJ, Kelsey JL, Kiel DP, Roman AM, Cupples LA, Freeman MB et al (2008) Issues in conducting epidemiological research among elders. Lessons from the MOBILIZE Boston study. Am J Epidemiol 168:1444–1451

Seidell JC, Visscher TL (2000) Body weight and weight change and their health implications in the elderly. Eur J Clin Nutr 54(Suppl3):S33–S39

Shields NA, O’Neill S, Murphy A, Rea IM (2002) Mortality outcomes in nonagenarians in the Belfast Elderly Longitudinal Free-living Ageing STudy (BELFAST). Age Ageing 31(suppl 1):22

Siani A, Cappuccio FP, Barba G, Trevisan M, Farinaro E, Lacone R et al (2002) The relationship of waist circumference to blood pressure; the Olivetti Heart Study. Am J Hypertens 15:780–786. doi:10.1016/S0895-7061(02)02976-X

Strazzullo P, Barba G, Cappuccio FP, Siani A, Trevisan M, Farinaro E et al (2001) Altered renal handling in men with abdominal adiposity; a link to hypertension. J Hypertens 19:2157–2164. doi:10.1097/00004872-200112000-00007

Weinberger MH, Fineberg NS (1991) Sodium and volume sensitivity of blood pressure; age and pressure changes over time. Hypertension 18:67–71

Whelton PK, Appel LJ, Espeland MA, Appelgate WB, Ettinger WH, Kostis JB (1998) Sodium reduction and weight loss in the treatment of hypertension in older persons: a randomized controlled trial of nonpharmacological interventions in the elderly (TONE). Tone Collab Res Group. JAMA 279:839–846

Williams GC (1957) Pleiotropy, natural selection, and the evolution of senscence. Evol Int J Org Evol 11:398–411. doi:10.2307/2406060

World Population Prospects The 2002 Revision. Highlights. United Nations Population Database, pp 16–17

Wright BM, Dore CF (1970) A random-zero sphygmomanometer. Lancet 764:337–343

Yates LB, Djousse L, Kurth T, Buring JE, Gaziano M (2008) Exceptional longevity in men. Modifiable factors associated with survival and function to age 90 years. Arch Intern Med 168:284–290. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2007.77

Acknowledgement

The Belfast Elderly Longitudinal Free-living Aging STudy (BELFAST) was originally funded, in part, by a grant from the Department of Health and Social Services (Northern Ireland).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Rea, I.M., Myint, P.K., Mueller, H. et al. Nature or nurture; BMI and blood pressure at 90. Findings from the Belfast Elderly Longitudinal Free-living Aging STudy (BELFAST). AGE 31, 261–267 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-009-9096-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-009-9096-1