Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study is to examine gender differences in physical activity status and knowledge of physical activity guidelines in University staff and students.

Methods

820 survey respondents, 419 males and 401 females (Age: mean 30 ± 12, median 24 years; Weight: mean 73.4 ± 15.8 kg; Stature: mean 172.1 ± 10.2 cm) were recruited via internal email. All participants completed a self-administered online format of the Global Physical activity Questionnaire.

Results

Less females were regularly active than males in students (p ≤ 0.001; Cramer’s V = 0.232 [small]), and staff (p = 0.003; Cramer’s V = 0.249 [small]). Overweight BMI incidence was greater among male students (p = 0.014; Cramer’s V = 0.13 [small]), and staff (p = 0.007; Cramer’s V = 0.31 [large]). A total of 43% of males and 29% of females were overweight or obese. No significant difference between genders for PA recommendations knowledge was observed (students; p = 0.174; Cramer’s V = 0.054 [trivial], staff; p = 0.691; Cramer’s V = 0.035 [trivial]). No significant difference between genders for disease incidence was observed (students; p = 0.894; Cramer’s V = 0.005 [trivial], staff; p = 0.237, Cramer's V = 0.101 [small]).

Conclusions

Males had greater levels of PA participation and incidence of overweight BMI compared to females. These findings suggest PA status alone does not determine BMI status. Further investigation is needed to determine factors related to BMI status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It has been widely documented that physical activity (PA) levels start to decline in adolescence and adulthood [1, 2], leading to subsequent increases in body weight [3, 4]. PA is defined as any bodily movement produced by the contraction of skeletal muscle that increases energy expenditure above a basal level [5]. PA is fundamental to the health and well-being of individuals with benefits including decreased levels of depression and anxiety and a decreased risk of non-communicable diseases (NCD) [6, 7]. In addition, compelling evidence suggests prolonged sedentary behaviour is linked with increased risks of several chronic adverse health conditions including type 2 diabetes mellitus, colon and breast cancers, coronary heart disease and increased mortality rate [8]. Physical inactivity is deemed to be the cause of an estimated 10% of all deaths caused by NCD’s [9].

Despite the reported benefits of PA to health and wellbeing [6, 7] a substantial decline in PA levels globally has been reported in recent years, for reasons such as increased use of entertainment technology [10]. This global pandemic of physical inactivity has become a major economic burden, conservatively estimated to cost $53.8 billion across healthcare systems worldwide in 2013 [11]. For example, inactive individuals on average spend 38% more days in hospital compared to active individuals and use significantly more healthcare resources [12]. A major cause for concern is the number of people not meeting the minimum recommendations for PA; evidence suggests a staggering 31% of the world’s population do not meet these minimum recommendations [13], as set out by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) of 30 min of moderate to intense PA on 5 or more days per week [14]. The ACSM stated the aim of the 1995 PA recommendations was to encourage PA participation by providing a clear and concise public health message [15]. In addition, the current PA guidelines outlined by The World Health Organization (WHO) since 2008 state that adults (including the elderly population) should partake in a minimum of 150 min of moderate to intense aerobic PA per week [16]. However, in addition to the lack of overall PA, evidence suggests that there is a lack of knowledge of these PA guidelines, which are well established; for example, Knox et al., (2013) reported only 18% of responders of the national survey in the UK were aware of these guidelines, in addition to only 11% of a 2007 sample who accurately recalled the previous PA recommendations [17]. However, promising evidence in China has shown that increased awareness of PA recommendations is associated with higher PA levels [18]. Exploring national awareness is important for future policy intervention, however no recent examination of Irish knowledge of PA guidelines or PA choices is available.

Future predictions for Ireland are not positive when it comes to health status; for example, a recent study estimates that by 2025, obesity is projected to increase in 44 countries, with the highest prevalence projected for Ireland at 43% [19]. As obesity and higher body weight is strongly linked with a lack of PA and a sedentary lifestyle [20], it is important to gain an understanding of why PA recommendations are not widely adhered to understand and address the issues. Interestingly, studies have shown gender differences exist in meeting the risk factors for NCD and perhaps should be considered separately; women were shown to have greater levels of inactivity and participated in less moderate-to-vigorous PA compared to men [21, 22]. Similar gender differences in PA levels have been displayed among children, adolescents, and adults, reporting males overall to engage in higher levels of PA compared to females [23, 24]. However, there remains a lack of current evidence within Ireland and specifically within University populations. Previous epidemiology studies have focused on data available from children in primary and secondary school [25,26,27], as well as from the general population [13, 28, 29]. It is important to gather data on PA levels from University populations as this period of adolescence to adulthood is often a pivotal transition, with PA levels in individuals at adolescence often reflected in adulthood [30]. In addition, we took the opportunity to also survey staff at University level and given that there is likely to be major lifestyle differences between students and staff in this University environment, we opted to consider these groups separately. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine differences in gender when comparing self-reported PA choices, BMI, health-related disease state and knowledge of PA guidelines, in staff and students within an Irish University. We hypothesised that males would be more active than females.

Methods

Participants

The survey was distributed via internal email to over 5000 staff and students at TU Dublin – Tallaght Campus, Dublin, and 820 completed the survey (Age: mean 30 ± 12, median 24 years; body mass: mean 73.4 ± 15.8 kg; Stature: mean 172.1 ± 10.2 cm). Male 419, Female 401. A sufficient representation of each year group and staff/postgraduate groups were observed (Year 1 = 267, year 2 = 146, year 3 = 134, year 4 = 96, postgraduate = 39, staff = 138). Participants were required to be over 18 years of age and digital informed consent was obtained at the beginning of the survey. Ethical approval was granted by the TU Dublin Ethics Committee.

Experimental design

A self-administered format of the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) was adapted on Survey Monkey to assess the levels of physical activity of respondents based on the original versions (available at http://www.who.int/chp/steps/GPAQ/en). The English version was adapted to a self-administered online survey format by rewording sentences such as ‘Next I am going to ask you…’ which are not appropriate in a self-administered version. English is the first language in Ireland, and this survey has been found to have fair to moderate validity in Europe [31]. Self-reported BMI has been found to be highly correlated to measured BMI (r = 0.87; N = 4566) but an under-reporting bias of 1.16 BMI is observed [32]. Respondents were asked to provide height (cm) and weight (kg), year of study (or staff/postgraduate), age, and were also asked the following: (1) “Have you ever been professionally diagnosed with any of the following (please tick all that apply): Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, Joint problems due to inactivity or being overweight, High blood pressure, High Cholesterol, Osteoporosis (low bone mass), Cardiovascular disease, Stroke, None. (2) “Do you believe that you are meeting recommended adult guidelines for regular physical activity?” (Please select one answer): Yes / No / I don’t know. (3) “Please state what you believe the current minimum guidelines for adult physical activity (per week) to be”: (Open text response). The survey took no longer than ten minutes to complete. Data collected were anonymised and protected in line with departmental policies and procedures at all times. The data that support the findings of the study are openly available in OSF at https://osf.io/n54sy/?view_only=07cd2cb96a6641d3aa419c2b42b65e5d.

Data processing

Following data capture, all non-completed surveys were eliminated from the final respondents list. GPAQ data were cleaned according to the GPAQ analysis guide of the WHO [16]. We calculated min/week spent in moderate and vigorous activities as well as the MET-min/week (metabolic equivalent); one MET is equal to the energy expended during rest (3.5 mL O2/kg/min). BMI was calculated from height and weight metrics using the equation BMI = kg/m2 where kg is a person's weight in kilograms and m2 is their height in metres squared. BMI was then categorised as < 18.5 = underweight, 18.5–24.9 = Normal weight, 25–29.9 = overweight, > 30 = obese.

To evaluate knowledge of PA guidelines, respondents were required to state either the CDC and ACSM guidelines of “30 min of moderate to intense PA on 5 or more days per week” [14], or otherwise the WHO guidelines of “a minimum of 150 min of moderate to intense aerobic PA per week”; failure to list either common guideline was considered as a lack of knowledge of these guidelines, and respondents were listed as either knowledgeable or unknowledgeable in this regard. We categorised participants into “Regularly Active” if they self-reported ≥ 150 min of moderate or vigorous (worth 2 moderate minutes) physical activity per week. Finally, the prevalence of each disease type was summed.

Data analysis

Before analysis, we grouped respondents into either “students” (Years 1, 2, 3, 4 and postgraduates; N = 682), or “staff” (N = 138). To examine the differences between genders, a series of three-way chi-square test of association (crosstabulations) were conducted on dependent variables comparing males and females with students/staff as the third layer binary variable. Strength of association was reported using Cramer's V; Cohen [33] suggested the following guidelines for interpreting Cramer's V; if Df = 1, Small > 0.1, Medium (Moderate) > 0.3, and Large > 0.5. if Df = 3, Small > 0.06, Medium (Moderate) > 0.17, and Large > 0.29. If cell frequencies were less than five for Chi squared tests, we implemented a Fisher’s Exact test instead. We also conducted a series of Mann Whitney U tests to examine differences in the total minutes of moderate/vigorous PA, as well as total METS, between genders, split by student/staff groups. All distributions of the scores for males and females were similar, as assessed by visual inspection. Statistical significance was accepted at α ≤ 0.05 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences data analysis software V22.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

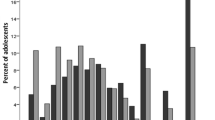

A Chi-square test of association was conducted between gender and BMI category. There was a statistically significant association between gender and BMI for students (χ2(3) = 10.58, p = 0.014, Cramer’s V = 0.13 [small]), and for staff (χ2(3) = 12.258, p = 0.007, Cramer’s V = 0.31 [large]). The BMI differences in gender can be observed in Fig. 1, which identifies a higher frequency of males in the overweight group, for both students and staff. All descriptive statistics can be observed in Table 1.

Comparison of BMI comparing male and female, divided into students / staff, presented as the frequency of observed cases. The percentage value represents incidence rate within the gender and student/staff category. BMI was categorised as < 18.5 = Underweight, 18.5–24.9 = Normal weight, 25–29.9 = Overweight, > 30 = Obese. There was a statistically significant association between gender and BMI for students (p = 0.014), and for staff (p = 0.007)

We also examined knowledge of current PA recommendations, with 105/308 (34%) males correctly reporting current guidelines compared to 88/375 females (23%) [69 cases were unanswered]. A Chi-square test for independence was conducted between gender and knowledge of PA recommendations; there was no statistically significant difference between gender and knowledge of PA recommendations, for either students (χ 2(1) = 1.847, p = 0.174, Cramer's V = 0.054 [trivial]), or staff (χ 2(1) = 0.158, p = 0.691, Cramer's V = 0.035 [trivial]).

A Chi-square test for independence was also conducted between gender and being regularly active (minimum guidelines). There was a statistically significant association between gender and being regularly active for students (χ2(1) = 36.698, p ≤ 0.001, Cramer's V = 0.232 [small]), and staff (χ2(1) = 8.527, p = 0.003, Cramer's V = 0.249 [small]). Overall, 278/419 (66%) of males participated regularly in PA compared to 172/403 (43%) females. In addition, we examined differences between gender for minutes of vigorous and moderate PA; A Mann–Whitney U test identified that in students, median vigorous PA minutes was statistically significantly higher in males (60 min) than in females (0 min), U = 69,543, z = 6.817, p ≤ 0.001, but not different in staff; males (15 min) than in females (0 min), U = 2,450, z = 1.04, p = 0.298. Median moderate PA minutes in students was statistically significantly higher in males (90 min) than in females (60 min), U = 61,405, z = 2.472, p = 0.013, and also in staff; males (100 min) than in females (42.5 min), U = 2,864, z = 2.651, p = 0.008. Differences between genders for minutes of vigorous and moderate PA can be observed in Fig. 2. Total METS was also examined—A Mann–Whitney U test identified that median Total METS in students was statistically significantly higher in males (1200) than in females (480), U = 74,607, z = 6.657, p ≤ 0.001, and also in staff; males (800) than in females (480), U = 2,958, z = 2.522, p = 0.012.

When we examined disease incidence between males (N = 419) and females (N = 403), overall, 61 males (14.6%) reported a disease incidence compared to 55 females (13.6%). There was no statistically significant difference between gender and disease incidence in students (χ2(1) = 0.018, p = 0.894, Cramer's V = 0.005 [trivial]), or in staff (χ2(1) = 1.396, p = 0.237, Cramer's V = 0.101 [small]). The distribution of specific diseases comparing gender can be observed in Table 2, where only a significant difference in cholesterol being higher in males in the staff cohort is observed. We also note that T2DM is also only present in males in this sample.

Discussion

The aim of this research study was to examine differences in gender when comparing self-reported physical activity status, BMI, health-related disease state and knowledge of PA guidelines, in staff and students within an Irish University. The findings of this study suggest that males were more likely to be overweight/obese with higher BMI overall compared to females. A total of 43% of males were found to be overweight or obese compared to 29% of females. However, as hypothesised males were found to engage in significantly higher levels of PA compared to females both at student and staff level, despite no difference in knowledge of PA guidelines between both genders. In addition, no difference between genders was observed in disease incidences for either group.

The present research identified that males were more likely to be overweight that females in both staff and students which is in line with findings from the Healthy Ireland Summary Report (2019) [34]. This is also observed in 2016 WHO reports in which European males overweight status was higher than European women [35], and this gender gap is thought to be increasing over time [36]. The overweight gender disparity is directly contradicting our findings on PA status where males are observed to have higher PA than females, and this suggests that either; gender responses to exercise may be different with respect to fat loss [37], or other factors outside of PA status may be responsible; for example, Kim and Shin (2020) suggest that males may be less concerned about their weight status or physical appearance than women, perceive exercise for fat loss as “feminine” or not have equal access to weight-loss programs that typically target women [36]. Therefore, future research should explore specific concerns with male obesity and the related factors.

This research study showed females participated in significantly less minutes of vigorous PA compared to males, which has been similarly displayed in previous studies [38,39,40]. Differences in PA levels between genders has been extensively studied and research consistently suggests males participate in greater levels of PA compared to females [23, 34, 42]. In 2019, an Irish health survey that found identical results to the present study reported that time restrictions are a key barrier to PA levels among adults. From this health survey 36% reported being too busy for PA due to work or study, 24% reported being too busy for PA due to caring for family and 7% reported being too busy for PA for other reasons [43]. Therefore, the present study is in line with other national publications, whilst providing specific insight into University staff and students as a subgroup of the population.

Interestingly we did not see any substantial differences in PA activities between staff and students despite a significant median age gap between the groups (students = 21/22 years, and staff = 45/51 years, for females / males, respectively). We would have expected a lower value for meeting the PA guidelines in the staff cohort, but the ratio of those meeting the guidelines were almost identical to students; one reason could be the relatively high socio-economic class and educational status of the staff which have both been shown to positively influence PA choices [44, 45]. A second reason may be that peak age-related PA decline occurs in the mid-to-late teens [46, 47], which may mean that our students (in their early twenties) have already established PA habits by this stage which reflects similar levels of PA as adults.

The results from this research study displayed no significant difference between genders for disease incidence except for cholesterol in the staff cohort, demonstrating increased incidence for males. This is concerning given the associations between cholesterol and vascular diseases [48] and future interventions should target this elevated risk factor. Our research suggests upwards of 29% of University male staff have presented with a health-related disease which is in line with the 32% reported in the Healthy Ireland Summary Report (2019). In addition, disease incidence presents the most notable difference between students and staff, with double the incidence in the staff group compared to students, and this elevated risk in staff should also be a target for future interventions.

Only 34% and 23% of males and females respectively were able to correctly report the current guidelines for PA. Similarly, a recent study examined the knowledge of PA guidelines among Portuguese college students and reported only 9.8% could accurately recall the current PA guidelines [43]. Although the lack of knowledge of PA guidelines remains an issue among University staff and students in Ireland, the recent Healthy Ireland Summary Report reported 64% of individuals not sufficiently active desire to increase their PA levels. Increasing awareness of PA guidelines through effective communication strategies is important to encourage individuals desiring to increase their activity levels.

Practical implications

The results from this research study suggest that despite more males meeting the PA guidelines and having a greater awareness of PA recommendations, males had higher levels of obesity when compared to females. This finding suggests that it is not PA status alone that is the single determining factor of BMI status. The findings from this study highlights the importance of obtaining further evidence and understanding of the important factors contributing to the health status of individuals such as age, diet, socioeconomic factors [49, 50] and psychosocial factors such as working hours, shift work and sleeping patterns [48, 49] In addition, given the prevalence and awareness of BMI as a measure of “health” in the general public, we face ongoing dangers that normal weight individuals will consider themselves at low risk of health-related disease [51]. However, both BMI and PA status need to be considered separately as risk factors, given their independent associations with these diseases in the literature.

The results from this research study highlight the concerning lack of participation in PA, particularly in females. These findings correspond with numerous research studies highlighting these issues are widespread and long-term among female populations worldwide [23, 41, 48]. Considering the known health benefits of regular PA regardless of BMI status, it is of vital importance that interventions and programs are implemented to increase PA participation, especially within female populations. Only 34% of males and 23% of females who participated in this study were aware of the current guidelines for PA. These figures display a need for more health promotion and awareness of PA guidelines and health benefits to address this issue. Recent evidence has shown individuals with knowledge of the health benefits associated with PA tend to be more active and individuals able to identify diseases associated with inactivity were also more active [52].

Limitations

There are several limitations to be considered when interpreting the results of this research study. The participants of this study were gathered from a convenience sample of non-randomized survey respondents from Technological University Dublin—Tallaght Campus. Therefore, the results of this study are not fully reflective of gender differences in PA choices across all Universities and Institutes in Ireland. Data for this research study were gathered using a self-report survey; self-report surveys pose numerous limitations including over-reporting and inaccurate recalling from memory [53]. Over-reporting of factors such as PA may often occur due to social desirability and social approval bias [54] which must be considered when interpreting this study. Finally, the cohort for this research study included a number of respondents in the field of sport science and health studies and this may positively skew the PA data as sport science students are likely to have greater engagement in team sports and PA overall compared to others in different disciplines.

Conclusion

Overall females had lower PA levels compared to males. The incidence of overweight BMI was higher among males compared to females. Therefore, despite males having higher PA levels and greater awareness of PA guidelines, overweight incidence was greater amongst males. This finding suggests it is not PA status alone that determines BMI status and further investigation is needed to determine factors relating to BMI status. This research study also highlighted the concerning lack of awareness of current PA guidelines among University students and staff, as well as the high prevalence of reported health related disease in staff. Greater health promotion is needed to increase the awareness of the current PA guidelines and promote PA participation.

References

Kimm SYS, Glynn NW, Kriska AM et al (2002) Decline in physical activity in black girls and white girls during adolescence. N Engl J Med 34:709–715. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa003277

Sigmund E, De Ste CM, Miklankova L, Fromel K (2007) Physical activity patterns of kindergarten children in comparison to teenagers and young adults. Eur J Public Health 17:646–651. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckm033

Faulkner GEJ, Buliung RN, Flora PK, Fusco C (2008) Active school transport, physical activity levels and body weight of children and youth: a systematic review. Prev Med (Baltim) 48:3–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.10.017

Hughes VA, Frontera WR, Roubenoff R, Evans WJ, Singh MAF (2002) Longitudinal changes in body composition in older men and women: role of body weight change and physical activity. Am J Clin Nutr 76:473–481. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/76.2.473

Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM (1985) Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep 100:126–131 (PMID: 3920711)

Reiner M, Niermann C, Jekauc D, Woll A (2013) Long-term health benefits of physical activity—a systematic review of longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health 13:813. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-813

Wegner M, Helmich I, Machado S, Nardi A, Arias-Carrion O, Budde H (2014) Effects of exercise on anxiety and depression disorders: review of meta-analyses and neurobiological mechanisms. CNS Neurol Disord - Drug Targets 13:1002–1014. https://doi.org/10.2174/1871527313666140612102841

Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Alleyne G et al (2011) UN high-level meeting on non-communicable diseases: addressing four questions. Lancet 378:449–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60879-9

Kohl HW, Craig CL, Lambert EV et al (2012) The pandemic of physical inactivity: global action for public health. Lancet 380:294–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60898-8

Ng SW, Popkin BM (2012) Time use and physical activity: a shift away from movement across the globe. Obes Rev 13:659–680. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00982.x

Ding D, Lawson KD, Kolbe-Alexander TL et al (2016) The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet 388:1311–1324. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30383-X

Sari N (2009) Physical inactivity and its impact on healthcare utilization. Health Econ 18:885–901. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1408

Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC et al (2012) Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet 380:247–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60646-1

Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN et al (1995) Physical activity and public health: a recommendation from the centers for disease control and prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. JAMA 273:402. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1995.03520290054029

Haskell WL, Lee I-M, Pate RR et al (2007) Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med Sci Sports Exerc 116:1081–1093. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0b013e3180616b27

World Health Organisation (2010) Global recommendations on physical activity for health. WHO Press. https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_recommendations/en/. Accessed 19 Oct 2020

Knox ECL, Esliger DW, Biddle SJH, Sherar LB (2013) Lack of knowledge of physical activity guidelines: can physical activity promotion campaigns do better? BMJ Open 3:e003633. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003633

Abula K, Gröpel P, Chen K, Beckmann J (2018) Does knowledge of physical activity recommendations increase physical activity among Chinese college students? Empirical investigations based on the transtheoretical model. J Sport Heal Sci 7:77–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JSHS.2016.10.010

Pineda E, Sanchez-Romero LM, Brown M et al (2018) Forecasting future trends in obesity across Europe: the value of improving surveillance. Obes Facts 11:360–371. https://doi.org/10.1159/000492115

Ángel Martínez-González M, Alfredo M, Gibney M, Kearney JM (1999) Physical inactivity, sedentary lifestyle and obesity in the European Union SUN Cohort View project Portion size estimation View project. Artic Int J Obes 46:53–5653. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0801049

Khan Khuwaja A, Masood Kadir M (2010) Gender differences and clustering pattern of behavioural risk factors for chronic non-communicable diseases: community-based study from a developing country. Chronic Illn 6:163–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742395309352255

Silva KS, Barbosa Filho VC, Del Duca GF et al (2014) Gender differences in the clustering patterns of risk behaviours associated with non-communicable diseases in Brazilian adolescents. Prev Med (Baltim) 65:77–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.YPMED.2014.04.024

Azevedo MR, Araújo CLP, Reichert FF, Siqueira FV, da Silva MC, Hallal PC (2007) Gender differences in leisure-time physical activity. Int J Public Health 52:8–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-006-5062-1

Trost SG, Pate RR, Sallis JF et al (2002) Age and gender differences in objectively measured physical activity in youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc 34:350–355. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005758-200202000-00025

Kelly LA, Reilly JJ, Grant S, Paton JY (2005) Low physical activity levels and high levels of sedentary behaviour are characteristic of rural Irish primary school children. Ir Med J 98:138–141 (PMID: 16010780)

Harrington DM, Belton S, Coppinger T et al (2014) Official Journal of ISPAH Results From Ireland’s 2014 Report Card on Physical Activity in Children and Youth. J Phys Act Health 11:63–68. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2014-0166

Riddoch C, Mahoney C, Murphy N, Boreham C, Cran G (2016) The physical activity patterns of Northern Irish Schoolchildren Ages 11–16 Years. Pediatr Exerc Sci 3:300–309. https://doi.org/10.1123/pes.3.4.300

MacAuley D, McCrum EE, Stott G et al (1998) Levels of physical activity, physical fitness and their relationship in the Northern Ireland Health and Activity Survey. Int J Sports Med 19:503–511. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-971952

Livingstone M, Robson PJ, McCarthy S et al (2001) Physical activity patterns in a nationally representative sample of adults in Ireland. Public Health Nutr 4:1107–1116. https://doi.org/10.1079/PHN2001192

Glenmark B, Hedberg G, Jansson E (1994) Prediction of physical activity level in adulthood by physical characteristics, physical performance and physical activity in adolescence: an 11-year follow-up study. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 69:530–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00239871

World Health Organisation (2017) Global Physical Activity Surveillance. WHO Press. http://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/steps/GPAQ/en/. Accessed 9 Nov 2020

Elgar FJ, Stewart JM (2008) Validity of self-report screening for overweight and obesity. Can J Public Health 99:423–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03405254

Cohen J (1992) Statistical power analysis. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 1:98–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10768783

Healthy Ireland (2019) Healthy Ireland Survey, Summary Report 2019. Government Publications. https://www.gov.ie/en/collection/231c02-healthy-ireland-survey-wave/. Accessed 17 Sept 2021

World Health Organisation (2016) Global Health Observatory (GHO) NCD risk factors: overweight and obesity. WHO Press. https://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/overweight/en

Kim KB, Shin YA (2020) Males with obesity and overweight. J Obes Metab Syndr 29:18–25. https://doi.org/10.7570/jomes20008

Aadland E, Jepsen R, Andersen JR, Anderssen SA (2014) Differences in fat loss response to physical activity among severely obese men and women. J Rehabil Med 46:363–369. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-1786

Hamrani A, Mehdad S, El KK et al (2014) Physical activity and dietary habits among Moroccan adolescents. Public Health Nutr 18:1793–1800. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980014002274

Luzak A, Heier M, Thorand B et al (2017) Physical activity levels, duration pattern and adherence to WHO recommendations in German adults. PLoS ONE 12(2):e0172503. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0172503

Bergier J, Bergier B, Tsos A (2017) Variations in physical activity of male and female students from the Ukraine in health-promoting lifestyle. Ann Agric Environ Med 24:217–221. https://doi.org/10.5604/12321966.1230674

Coen SE, Subedi RP, Rosenberg MW (2016) Working out across Canada: Is there a gender gap? Can Geogr 60:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12255

Singh A (2019) Gender Differences of Physical Activity in University Students. Int J Yogic Hum Mov Sports Sci 4:374–377. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331950326. Accessed October 21, 2019.

Martins J, Sarmento H, Marques A, Nicola PJ (2019) Physical Activity Recommendations for Health: Knowledge and Perceptions among College Students. Retos 36:290–296. http://hdl.handle.net/10451/39960

Talaei M, Rabiei K, Talaei Z, Amiri N, Zolfaghar B, Kabiri P, Sarrafzadegan N (2013) Physical activity, sex and socioeconomic status: a population-based study. ARYA Atheroscler 9:51–60 (PMID: 23696760)

Trost SG, Owen N, Bauman AE, Sallis JF, Brown W (2002) Correlates of adults’ participation in physical activity: review and update. Med Sci Sports Exerc 34:1996–2001. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200212000-00020

Caspersen CJ, Pereira MA, Curran KM (2000) Changes in physical activity patterns in the United States, by sex and cross-sectional age. Med Sci Sports Exerc 32:1601–1609. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200009000-00013

Telama R, Yang X (2000) Decline of physical activity from young adulthood in Finland. Med Sci Sports Exerc 32:1617–1622. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200009000-0015

Vilhjalmsson R, Thorlindsson T (1998) Factors related to physical activity: a study of adolescents. Soc Sci Med 47:665–675. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00143-9

Lapidus L, Bengtsson C (1986) Socioeconomic factors and physical activity in relation to cardiovascular disease and death. A 12 year follow up of participants in a population study of women in Gothenburg, Sweden. Br Heart J 55:295–301. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.55.3.295

Kuntz B, Lampert T (2010) Socioeconomic factors and the distribution of obesity. Dtsch Arztebl 107:517–522. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2010.0517

Rothman KJ (2008) BMI-related errors in the measurement of obesity. Int J Obes 32:S56–S59. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2008.87

Fredriksson SV, Alley SJ, Rebar AL, Hayman M, Vandelanotte C, Schoeppe S (2018) How are different levels of knowledge about physical activity associated with physical activity behaviour in Australian adults? PLoS ONE 13:e0207003. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207003

Prince SA, Adamo KB, Hamel ME, Hardt J, Connor Gorber S, Tremblay M (2008) A comparison of direct versus self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 5:56. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-5-56

Grimm P (2010) Social Desirability Bias. In: Wiley International Encyclopaedia of Marketing. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444316568.wiem02057

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all volunteers who participated in this research investigation.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium. None to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CM had the primary responsibility for writing the manuscript. Warne devised the project and its main conceptual ideas, devised the study design, collected, and analysed the data and edited and co-wrote the final paper version. All authors have read and approved the final paper version of the manuscript and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Availability of data/material

The data that support the findings of the study are openly available in OSF at: https://osf.io/n54sy/?view_only=07cd2cb96a6641d3aa419c2b42b65e5d.

The authors declare this research paper has not been published previously, is not under consideration for publication elsewhere, its publication is approved by all authors and tacitly or explicitly by the responsible authorities where the work was carried out, and that, if accepted, it will not be published elsewhere in the same form, in English or in any other languages, including electronically without the written consent of the copyright holder.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The authors declare that all procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the ethics research committee of Technological University Dublin – Tallaght Campus and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its latest amendments.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants involved in this research study.

Consent to participate

All participants provided explicit consent to participate.

Consent for publication

All contributing authors have given consent for publication and confirm that they have approved the final version of the manuscript and have made all required statements and declarations.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McCarthy, C., Warne, J.P. Gender differences in physical activity status and knowledge of Irish University staff and students. Sport Sci Health 18, 1283–1291 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-022-00898-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-022-00898-0