Abstract

Purpose

This systematic review was conducted to answer the following 3 questions: ‘Does nasal pathology affect CPAP use?’, ‘What is the effect of CPAP on the nose?’ and ‘Does treatment of nasal pathology affect CPAP use?’.

Methods

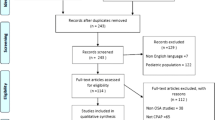

Pubmed and Scopus databases were searched for articles relevant to the study questions up to October 2020.

Results

Sixty-three articles were selected, of which a majority were observational studies. Most studies identified a correlation between larger nasal cross-sectional area or lower nasal resistance and higher CPAP compliance or lower CPAP pressures; however, nasal symptoms at baseline did not appear to affect CPAP use. The effect of CPAP on the nose remains uncertain: while most studies suggested increased mucosal inflammation with CPAP, those investigating symptoms presented contradictory results, with some reporting an increase and others an improvement in nasal symptoms. Evidence is clearer for nasal surgery leading to an increase in CPAP compliance and a decrease in CPAP pressures, whereas there is little evidence available for the use of topical nasal steroids.

Conclusion

There appears to be a link between nasal volumes or nasal resistance and CPAP compliance, an increase in nasal inflammation caused by CPAP and a beneficial effect of nasal surgery on CPAP usage, but no significant effect of CPAP on nasal patency or effect of topical steroids on CPAP compliance. Results are more mitigated with regard to the effect of nasal symptoms on CPAP use and vice versa, and further research in this area would help identify patients who may benefit from additional support or treatment alongside CPAP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Articles listed on Pubmed and Scopus were used.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

American Academy of Sleep Medicine (2001) The international classification of sleep disorders, revised: diagnostic and coding manual. Illinois, Chicago

Senaratna C et al (2017) Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in the general population: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev 34:70–81

Marshall N et al (2008) Sleep apnea as an independent risk factor for all-cause mortality: the Busselton Health Study. Sleep 31(8):1079–85

Young T et al (1997) Sleep-disordered breathing and motor vehicle accidents in a population-based sample of employed adults. Sleep 20(8):608–13

Sateia M (2014) International classification of sleep disorders-third edition: highlights and modifications. Chest 146(5):1387–1394

Sullivan C et al (1981) Reversal of obstructive sleep apnoea by continuous positive airway pressure applied through the nares. Lancet 1(8225):862–5

American Thoracic Society (1994) Indications and standards for use of nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in sleep apnea syndromes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 150:1738–1745

Giles T et al (2006) Continuous positive airways pressure for obstructive sleep apnoea in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 25(1):CD001106

Weaver T, Sawyer A (2010) Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure treatment for obstructive sleep apnoea: implications for future interventions. Indian J Med Res 131:245–58

Kohler M et al (2010) Predictors of long-term compliance with continuous positive airway pressure. Thorax 65(9):829–32

Randerath W et al (2002) Efficiency of cold passover and heated humidification under continuous positive airway pressure. Eur Respir J 20(1):183–6

Massie C et al (1999) Effects of humidification on nasal symptoms and compliance in sleep apnea patients using continuous positive airway pressure. Chest 116(2):403–8

Mador M et al (2005) Effect of heated humidification on compliance and quality of life in patients with sleep apnea using nasal continuous positive airway pressure. Chest 128(4):2151–8

Hollandt J, Mahlerwein M (2003) Nasal breathing and continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Sleep & breathing 7(2):87–94

Rauscher H et al (1991) Acceptance of CPAP therapy for sleep apnea. Chest 100(4):1019–23

Catcheside P (2010) Predictors of continuous positive airway pressure adherence. Med Rep 2:70

Kalan A et al (1999) Adverse effects of nasal continuous positive airway pressure therapy in sleep apnoea syndrome. J Laryngol Otol 113(10):888–92

Georgalas C (2011) The role of the nose in snoring and obstructive sleep apnoea: an update. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 268(9):1365–1373

Masdeu M et al (2011) Awake measures of nasal resistance and upper airway resistance on CPAP during sleep. J Clin Sleep Med: JCSM: official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine 7(1):31–40

Li H et al (2005) Acoustic reflection for nasal airway measurement in patients with obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. Sleep 28(12):1554–9

Mo S et al (2021) Nasal peak inspiratory flow in healthy and obstructed patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope 131(2):260–267

Desfonds P et al (1998) Nasal resistance in snorers with or without sleep apnea: effect of posture and nasal ventilation with continuous positive airway pressure. Sleep 21(6):625–32

Stewart M et al (2004) Development and validation of the Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) scale. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 130(2):157–163

Juniper E et al (1999) Validation of the standardized version of the Rhinoconjunctivitis Quality of Life Questionnaire. J Allergy Clin Immunol 104(2 Pt 1):364–9

Rhee J et al (2014) A systematic review of patient-reported nasal obstruction scores: defining normative and symptomatic ranges in surgical patients. JAMA Facial Plast Surg 16(3):219–25

Howarth P et al (2005) Objective monitoring of nasal airway inflammation in rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 115(3 Suppl 1):S414-41

Morris L et al (2006) Acoustic rhinometry predicts tolerance of nasal continuous positive airway pressure: a pilot study. Am J Rhinol 20(2):133–7

Park P et al (2017) Influencing factors on CPAP adherence and anatomic characteristics of upper airway in OSA subjects. Medicine 96(51):e8818

Värendh M et al (2019) PAP treatment in patients with OSA does not induce long-term nasal obstruction. J Sleep Res 28(5):e12768

So Y et al (2009) Initial adherence to autotitrating positive airway pressure therapy: influence of upper airway narrowing. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol 2(4):181–5

Haddad F et al (2013) The influence of nasal abnormalities in adherence to continuous positive airway pressure device therapy in obstructive sleep apnea patients. Sleep Breath 17(4):1201–7

Kim H et al (2007) Influence of upper airway narrowing on the effective continuous positive airway pressure level. Laryngoscope 117(1):82–5

Camacho M et al (2016) Inferior turbinate size and CPAP titration based treatment pressures: no association found among patients who have not had nasal surgery. Int J Otolaryngol, Epub 2016

Wakayama T, Suzuki M, Tanuma T (2016) Effect of nasal obstruction on continuous positive airway pressure treatment: computational fluid dynamics analyses. PloS One 11(3):e0150951

Sugiura T et al (2007) Influence of nasal resistance on initial acceptance of continuous positive airway pressure in treatment for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Respiration 74(1):56–60

Inoue A et al (2019) Nasal function and CPAP compliance. Auris Nasus Larynx 46(4):548–558

Hsu Y et al (2020) Role of rhinomanometry in the prediction of therapeutic positive airway pressure for obstructive sleep apnea. Respir Res 21(1):115

Hueto J et al (2016) Usefulness of rhinomanometry in the identification and treatment of patients with obstructive sleep apnoea: an algorithm for predicting the relationship between nasal resistance and continuous positive airway pressure. a retrospective study. Clin Otolaryngol 41(6):750–757

Parikh N et al (2014) Clinical control in the dual diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and rhinitis: a prospective analysis. Am J Rhinol allergy 28(1):e52-5

Kreivi H et al (2010) Frequency of upper airway symptoms before and during continuous positive airway pressure treatment in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Respiration 80(6):488–94

Shadan F et al (2005) Nasal cytology: a marker of clinically silent inflammation in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and a predictor of noncompliance with nasal CPAP therapy. J Clin Sleep Med 1(3):266–270

Hoffstein V et al (1992) Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea with nasal continuous positive airway pressure. Patient compliance, perception of benefits, and side effects. Am Rev Respir Dis 145(4 Pt 1):841–845

Pépin J et al (1995) Side effects of nasal continuous positive airway pressure in sleep apnea syndrome. Study of 193 patients in two French sleep centers. Chest 107(2):375–81

Meslier N et al (1998) A French survey of 3,225 patients treated with CPAP for obstructive sleep apnoea: benefits, tolerance, compliance and quality of life. Eur Respir J 12(1):185–92

Lam A et al (2017) Validated measures of insomnia, function, sleepiness, and nasal obstruction in a CPAP alternatives clinic population. J Clin Sleep Med 13(8):949–957

Baltzan M, Elkholi O, Wolkove N (2009) Evidence of interrelated side effects with reduced compliance in patients treated with nasal continuous positive airway pressure. Sleep Med 10(2):198–205

Duong M et al (2005) Use of heated humidification during nasal CPAP titration in obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Eur Respir J 26(4):679–85

Koutsourelakis I et al (2011) Nasal inflammation in sleep apnoea patients using CPAP and effect of heated humidification. Eur Respir J 37(3):587–94

Yu C et al (2013) The effects of heated humidifier in continuous positive airway pressure titration. Sleep Breath 17(1):133–138

Lojander J, Brander P, Ammälä K (1999) Nasopharyngeal symptoms and nasal continuous positive airway pressure therapy in obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Acta Otolaryngol 119(4):497–502

Pitts K et al (2018) The effect of continuous positive airway pressure therapy on nasal patency. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 8(10):1136–1144

Cisternas A et al (2017) Effects of CPAP in patients with obstructive apnoea: is the presence of allergic rhinitis relevant? Sleep Breath 21(4):893–900

Skirko J et al (2020) Association of allergic rhinitis with change in nasal congestion in new continuous positive airway pressure users. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 146(6):523–529

Rakotonanahary D et al (2001) Predictive factors for the need for additional humidification during nasal continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Chest 119(2):460–5

Ruhle K et al (2011) Quality of life, compliance, sleep and nasopharyngeal side effects during CPAP therapy with and without controlled heated humidification. Sleep Breath 15(3):479–485

Brander P, Soirinsuo M, Lohela P (1999) Nasopharyngeal symptoms in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome Effect of nasal CPAP treatment. Respiration 66(2):128–135

Yang Q et al (2018) Effect of continuous positive airway pressure on allergic rhinitis in patients with obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. Ther Clin Risk Manag 14:1507–1513

Balsalobre L et al (2017) Acute impact of continuous positive airway pressure on nasal patency. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 7(7):712–717

İriz A et al (2017) Does nasal congestion have a role in decreased resistance to regular CPAP usage? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 274(11):4031–4034

Alahmari M et al (2012) Dose response of continuous positive airway pressure on nasal symptoms, obstruction and inflammation in vivo and in vitro. Eur Respir J 40(5):1180–90

Skoczyński S et al (2008) Short-term CPAP treatment induces a mild increase in inflammatory cells in patients with sleep apnoea syndrome. Rhinology 46(2):144–50

Bossi R et al (2004) Effects of long-term nasal continuous positive airway pressure therapy on morphology, function, and mucociliary clearance of nasal epithelium in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Laryngoscope 114(8):1431–4

Lacedonia D et al (2011) Effect of CPAP-therapy on bronchial and nasal inflammation in patients affected by obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Rhinology 49(2):232–7

Gelardi M et al (2012) Regular CPAP utilization reduces nasal inflammation assessed by nasal cytology in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep Med 13(7):859–63

Constantinidis J et al (2000) Fine-structural investigations of the effect of nCPAP-mask application on the nasal mucosa. Acta Otolaryngol 120(3):432–7

Almendros I et al (2008) Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) induces early nasal inflammation. Sleep 31(1):127–31

Vilaseca I et al (2016) Early effects of continuous positive airway pressure in a rodent model of allergic rhinitis. Sleep Med 27–28:25–27

Sommer J et al (2014) Functional short- and long-term effects of nasal CPAP with and without humidification on the ciliary function of the nasal respiratory epithelium. Sleep Breath 18(1):85–93

White D, Nates R, Bartley J (2017) Model identifies causes of nasal drying during pressurised breathing. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 243:97–100

Fischer Y et al (2008) Effects of nasal mask leak and heated humidification on nasal mucosa in the therapy with nasal continuous positive airway pressure (nCPAP). Sleep Breath 12(4):353–357

Camacho M et al (2015) The effect of nasal surgery on continuous positive airway pressure device use and therapeutic treatment pressures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep 38(2):279–86

Powell N et al (2001) Radiofrequency treatment of turbinate hypertrophy in subjects using continuous positive airway pressure: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical pilot trial. Laryngoscope 111(10):1783–90

Friedman M et al (2000) Effect of improved nasal breathing on obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 122(1):71–74

Sufioğlu M et al (2012) The efficacy of nasal surgery in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a prospective clinical study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 269(2):487–494

Nakata S et al (2005) Nasal resistance for determinant factor of nasal surgery in CPAP failure patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Rhinology 43(4):296–9

Poirier J, George C, Rotenberg B (2014) The effect of nasal surgery on nasal continuous positive airway pressure compliance. Laryngoscope 124(1):317–9

Zonato A et al (2006) Upper airway surgery: the effect on nasal continuous positive airway pressure titration on obstructive sleep apnea patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 263(5):481–486

Sériès F, St Pierre S, Carrier G (1992) Effects of surgical correction of nasal obstruction in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis 146(5 Pt 1):1261–5

Bican A et al (2010) What is the efficacy of nasal surgery in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome? J Craniofac Surg 21(6):1801–6

Iwata N et al (2020) Clinical indication of nasal surgery for the CPAP intolerance in obstructive sleep apnea with nasal obstruction. Auris Nasus Larynx 47(6):1018–1022

Means C, Camacho M, Capasso R (2016) Long-term outcomes of radiofrequency ablation of the inferior turbinates. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 68(4):424–428

Modica D et al (2018) Functional nasal surgery and use of CPAP in OSAS patients: our experience. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 70(4):559–565

Kempfle J et al (2017) A cost-effectiveness analysis of nasal surgery to increase continuous positive airway pressure adherence in sleep apnea patients with nasal obstruction. Laryngoscope 127(4):977–983

Ryan S et al (2009) Effects of heated humidification and topical steroids on compliance, nasal symptoms, and quality of life in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome using nasal continuous positive airway pressure. J Clin Sleep Med 5(5):422–427

Strobel W et al (2011) Topical nasal steroid treatment does not improve CPAP compliance in unselected patients with OSAS. Respir Med 105(2):310–5

Charakorn N et al (2017) The effects of topical nasal steroids on continuous positive airway pressure compliance in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Breath 21(1):3–8

Gelardi M et al (2019) Internal nasal dilator in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and treated with continuous positive airway pressure. Acta bio-medica : Atenei Parmensis 90(2-S):24–27

Collen J et al (2009) Clinical and polysomnographic predictors of short-term continuous positive airway pressure compliance. Chest 135(3):704–709

Kennedy B et al (2019) Pressure modification or humidification for improving usage of continuous positive airway pressure machines in adults with obstructive sleep apnoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 12(12):CD003531

Tárrega J et al (2003) Nasal resistance and continuous positive airway pressure treatment for sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Arch Bronconeumol 39(3):106–10

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Marina Brimioulle co-designed the study questions and the protocol, searched databases for relevant studies and prepared the draft of the manuscript. Konstantinos Chaidas co-designed the study questions and the protocol, critically reviewed the studies selected for inclusion and critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Comment

CPAP is usually considered the gold standard treatment for OSA patients; however, the rate of compliance is its major obstacle. Managing different nasal pathologies would help patients and might affect CPAP tolerance. Nasal surgery in OSA is pivotal in terms of improving airflow dynamics. In a multilevel surgical plan, the nose should be considered, and its repair will significantly aid in the success rate of OSA surgery. The restoration of a patent nasal airway is also effective in increasing tolerance for CPAP that is delivered via a nasal or a full-face mask, if needed.

Sherif Mohammad Askar

Egypt

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brimioulle, M., Chaidas, K. Nasal function and CPAP use in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea: a systematic review. Sleep Breath 26, 1321–1332 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-021-02478-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-021-02478-x