Abstract

The current monetary policy debate has focused on current estimates and the future path of the natural rate of unemployment and the equilibrium interest rate. Estimates of the natural rate of unemployment should vary over time with changes in demographics and improvements in human capital. However, these changes should be gradual. This paper shows that the estimates of the natural rate of unemployment by Federal Reserve officials and private-sector economists seem to move pro-cyclically, potentially showing too much weight given to short-term fluctuations in economic variables. As with the natural rate, there are good reasons to expect the equilibrium interest rate to change over time. In fact, the level may actually be more responsive to current economic data, reflecting changes in aggregate savings and investment. Yet, we see that equilibrium interest rate estimates by both Federal Reserve officials and private-sector economists have declined quite dramatically over the past five years. A potential concern raised in this paper is that estimates of these critical economic variables for policy determination appear to be overly sensitive to high frequency economic data.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), Eurostat, Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (MHLW), Haver Analytics

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA); Eurostat; Japan’s Ministry of Internal Affairs & Communications (MIC), Bank of Japan; Haver Analytics. Note: Japan’s inflation series is adjusted for an April 2014 consumption tax increase. For Japan and the Euro Area, the inflation measure is the change in the CPI. For the U.S., it is the change in the personal consumption expenditures price index

Source: FOMC, Summary of Economic Projections; CBO; Haver Analytics. Note: The central tendency excludes the three highest and three lowest observations. Prior to the June 2015 median, SEP median unemployment rates are publicly available only with a five-year lag. Proxies for the medians for 2012 – March 2015 are calculated from the distribution of participants’ projections reported in ranges of tenths in the meeting minutes

Source: BLS, CBO, Haver Analytics

Source: BLS, Haver Analytics

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Survey of Professional Forecasters. Note: The interquartile range is the 25th–75th percentiles

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Survey of Primary Dealers. Note: The interquartile range is the 25th–75th percentiles

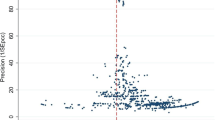

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Survey of Professional Forecasters; FOMC, Summary of Economic Projections (SEP); CBO; Haver Analytics. Note: The central tendency excludes the three highest and three lowest observations. Prior to the June 2015 (2015:Q2) median, SEP median unemployment rates are publicly available only with a five-year lag. Proxies for the medians for 2012-March 2015 (2015:Q1) are calculated from the distribution of participants’ projections reported in ranges of tenths in the meeting minutes

Source: FOMC, Summary of Economic Projections; BLS; CBO; Haver Analytics. Prior to the June 2015 (2015:Q2) median, SEP median unemployment rates are publicly available only with a five-year lag. Proxies for the medians for 2012-March 2015 (2015:Q1) are calculated from the distribution of participants’ projections reported in ranges of tenths in the meeting minutes

Source: FOMC, Summary of Economic Projections. Note: The central tendency exclude the three highest and three lowest observations

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Survey of Primary Dealers. Note: The interquartile range is the 25th–75th percentiles

Source: Blue Chip Economic Indicators, December 10, 2017

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The views I express are my own, not necessarily those of my colleagues on the Federal Reserve Board or the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). This paper is an expanded version of what was given as the 2017 William S. Vickery Distinguished Address at the 84th International Atlantic Economic Conference in Montreal on October 7, 2017.

That is, of the level of unemployment associated with full employment in the economy.

For example, if central bankers had assumed in 2010 that the natural rate of unemployment had risen toward 9%, they would have been incorrect, as the data since then have shown.

For additional perspective on the economic recovery in the wake of the financial crisis, see Rosengren (2016).

A common concept of slack employed in this context is the amount of labor market slack, usually taken as the difference between the actual unemployment rate and the rate that is consistent with full employment, called the natural rate. When unemployment is at the natural rate, the labor market does not exert pressure to move the inflation rate away from the central bank’s goal for inflation (2% in the U.S.). Thus, this definition of slack depends on obtaining an estimate of the natural rate of unemployment, a well-defined but difficult-to-measure quantity.

FOMC meeting participants (members of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors and the 12 Federal Reserve Bank Presidents) submit economic projections in conjunction with four FOMC meetings a year. A summary of these economic projections is released just prior to the press conferences (Federal Open Market Committee 2009–2017).

The Survey of Professional Forecasters is a quarterly survey of macroeconomic forecasts conducted by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia (1996–2017).

The New York Fed surveys primary dealers on their expectations for the economy, monetary policy and financial market developments prior to Federal Open Market Committee meetings (Federal Reserve Bank of New York 2011–2017).

If the estimates from the Survey of Primary Dealers were added to the chart, the observations would be nearly superimposed on the estimates from the Survey of Professional Forecasters as they are so similar.

Such movements in the estimates of an important underlying variable for measuring tightness in the labor market highlight that estimates can be too sensitive to recent underlying data. The CBO estimate of the natural rate tends to move only gradually, consistent with slow moving demographic variables, while the SEP estimates move much more. This suggests some caution in being too sensitive to incoming data relative to economic relationships that generally are believed to move only slowly.

References

Aaronson, D., Hu, L., Seifoddini, A., & Sullivan, D. G. (2015). Changing labor force composition and the natural rate of unemployment. Chicago Fed Letter, No. 338. Available at: https://www.chicagofed.org/publications/chicago-fed-letter/2015/338.

Blue Chip Publications (2017). Blue Chip economic indicators. Aspen Publishers. Vol. 42(12), December 10, 2017. Available at: https://lrus.wolterskluwer.com/store/blue-chip-publications/.

Federal Open Market Committee (2009–2017). Summary of Economic Projections. Available at: https://www.federalreserve.gov/faqs/summary-economic-projections-sep.htm.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York (2011–2017). Survey of Primary Dealers. Available at: https://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/primarydealer_survey_questions.html.

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia (1996–2017). Survey of Professional Forecasters. Available at: https://www.philadelphiafed.org/research-and-data/real-time-center/survey-of-professional-forecasters.

Rosengren, E. S. (2016). After the Great Recession, a Not-So-Great Recovery. Speech given at the 60th Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Conference, October 14, 2016. Available at: https://www.bostonfed.org/news-and-events/speeches/2016/after-the-great-recession-a-not-so-great-recovery.aspx.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rosengren, E.S. Estimating Key Economic Variables: The Policy Implications. Atl Econ J 46, 139–150 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-018-9572-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-018-9572-z