Abstract

Objectives

The current review assesses the methodological characteristics of between-subjects experiments, in particular documenting the scenarios and treatments described in each vignette, the extent to which confounds are embedded or accounted for in the design, and the analytic approach to estimating direct and interaction effects.

Methods

We conducted a pre-registered systematic review of 20 publications containing 20 independent studies and 23 vignette scenarios.

Results

We find that the majority of studies rely on non-probability convenience sampling, manipulate a combination of procedural justice elements at positive and negative extremes, but often do not address potential confounds or threats to internal validity. The procedural justice manipulations that combine different elements show relatively consistent associations with a range of attitudinal outcomes, whereas the results for manipulations that test individual components of procedural justice (e.g., voice) are more mixed.

Conclusions

Based on our review, we recommend that future studies using text-based vignettes disaggregate different elements of procedural justice in manipulations, and include a gradient of treatment or behavior (including control) to avoid comparing extremes, to incorporate potential confounders as either fixed covariates or manipulations, and to formally assess the information equivalence assumption using placebo tests.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to procedural justice theory, when police treat people with fairness, respect, and transparency, individuals are more likely to perceive the police as trustworthy and legitimate (Tyler, 2006). Each interaction with the police is considered a “teachable moment,” which is expected to influence interaction-specific as well as global attitudes toward police procedural justice and legitimacy (Mazerolle et al., 2013a, 2013b). Experimental vignettes, also called factorial survey experiments, are increasingly used to evaluate the factors that influence judgments about police procedural justice and legitimacy. Survey experiments have for example been used to vary individual and officer characteristics (Schuck et al., 2021; Solomon, 2019), treatment and outcome characteristics (Nivette & Akoensi, 2019; Reisig et al., 2018; Solomon & Chenane, 2021), and contextual or background characteristics (Jones et al., 2021). Vignettes allow researchers to construct a scenario describing a particular situation while systematically varying key characteristics that are hypothesized to influence the outcome (Aguinis & Bradley, 2014; Atzmüller & Steiner, 2010; Auspurg & Hinz, 2015). Between-subject survey experiments typically manipulate a small number of key variables and randomly assign one of the possible scenarios to each respondent. As such, survey experiments also address several threats to internal validity, such as self-selection, and therefore improve our understanding of the factors that shape public opinion and behavior in the real world (Dafoe et al., 2018; Gaines et al., 2007).

However, there are several potential issues to consider when evaluating the reliability and validity of treatment effects in between-subjects survey experiments. This can include the construction of scenarios and manipulations, evaluating assumptions about causal inference, and the testing of direct and interaction effects (Dafoe et al., 2018; Gaines et al., 2007). Such issues can limit the substantive testing of procedural justice theory as well as the statistical conclusions drawn about the results.

The current study therefore aims to critically review the use of experimental vignettes used in research on police procedural justice and legitimacy. This review focuses particularly on assessing the methodological characteristics of between-subjects experiments, in particular documenting the scenarios and treatments described in each vignette, the extent to which confounds are embedded or accounted for in the design, and the analytic approach to estimating direct and interaction effects. In doing so, we aim to provide an overview of different scenarios and treatments for use in replication and future studies, and a critical evaluation of methodological issues that can limit conclusions based on these types of survey experiments. A secondary goal of this review is to summarize the existing research evidence on factors that influence public perceptions of procedural justice and legitimacy.

Procedural justice theory

The main tenant of procedural justice theory is based on the idea that interactions with the police play an important role in shaping perceptions of procedural justice and legitimacy, willingness to assist the police, and compliance with the law (Tyler & Huo, 2002). The theory proposes that these outcomes are influenced more by the way police treat individuals (i.e., fair processes) than instrumental concerns or the fairness of the outcome (i.e., distributive justice) (McLean, 2020; Murphy et al., 2016). Procedurally just treatment also works to communicate an individual’s position and status within society, and can strengthen the social bond with institutions (Tyler & Huo, 2002). As Bradford et al., (2014, p. 528) put it, “[f]air treatment communicates that ‘we respect you and we see you as a worthwhile member of this community.’” Procedurally just treatment is said to consist of two main dimensions regarding the quality of treatment and decision-making (Solomon & Chenane, 2021; Sunshine & Tyler, 2003). Treatment quality is determined by the degree to which the officer treats the person with dignity and respect, and the extent to which the officer acts with honest intentions (trustworthy motives) (Solomon, 2019). In experimental vignettes, trustworthy motives are often depicted by the officer explaining his/her rationale for the contact or interaction, such as to prevent traffic accidents or keep roads safe (e.g., Maguire et al., 2017). Decision-making quality refers to the extent to which the officer makes decisions in a neutral manner, based on facts, and whether the officer allows the individual to voice their opinions during the encounter (Sunshine & Tyler, 2003; Trinkner & Cohn, 2014).

Survey research tends to find consistent associations between overall measures or components of procedural justice and perceptions of police legitimacy, trust, and cooperation (Murphy et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2017; Tankebe, 2013; Walters & Bolger, 2019; White et al., 2016). While this association has been found across countries, subpopulations, and to some extent measurement (Pina-Sánchez & Brunton-Smith, 2020), some have pointed to an asymmetry in the effect of procedurally just treatment on attitudes (Maguire et al., 2017). The asymmetry hypothesis refers to the notion that “bad” experiences are thought to have stronger effects on affective emotions and outcomes compared to “good” experiences (Skogan, 2006). For example, Wolfe and McLean (2021) found that experiences of procedurally just treatment were only weakly correlated with citizen perceptions of procedural justice, whereas experiences of injustice were relatively more strongly related to perceptions. This means that what is objectively considered just according to principles of procedural justice may not be interpreted as just according to the public. Perceptions of procedural justice have been shown to be rooted in broader social relationships, environments, and political views (Pickett et al., 2018; Roché & Roux, 2017). As such, while associations are consistent, there is evidence that procedural justice as a “treatment” in the experimental sense may have heterogeneous effects depending on the subjective interpretation of the experience.

Studies that have distinguished between quality of treatment and decision-making generally found that the quality of treatment, notably respect, tends to be more strongly correlated with attitudinal outcomes compared to decision-making (Hinds & Murphy, 2007; Reisig et al., 2007; Solomon, 2019). Recent research also suggests that procedural justice can also influence perceptions of distributive justice, as measured by outcome fairness, which subsequently correlated with legitimacy, trust, and cooperation (McLean, 2020; Solomon & Chenane, 2021).

Methodological issues related to experimental vignettes

While the use of experimental or factorial survey vignettes has increased across social science (Wallander, 2009), researchers have highlighted a number of important methodological issues to consider when constructing and testing treatment effects (Dafoe et al., 2018; Gaines et al., 2007; Hauser et al., 2018; Metcalfe & Pickett, 2021). First, the scenarios depicted in the survey experiments can portray very different actors and situations, with a varying amount and type of treatments. While realistic scenarios can improve external validity (Findley et al., 2021), it is not clear to what extent the results from different situations are comparable and consistent. The operationalization of treatments within scenarios may also differ across studies. Often the manipulation involves comparing two treatments (e.g., respectful vs. disrespectful treatment by officers) without a “business-as-usual” control group (Gaines et al., 2007). This makes it difficult to determine to what extent which (or both) frames influence the outcome.

Second, random assignment of treatment variables is not always enough to make causal inferences about epistemic effects on subjects’ beliefs (Dafoe et al., 2018). While randomization usually achieves this goal in a controlled experiment (Shadish et al., 2002), the manipulation of certain attributes within a scenario is likely to affect broader background beliefs about the scenario as well. Dafoe et al. (2018) argue that causal inference in these designs depends on the assumption of information equivalence, which has been referred to variously as “information leakage,” “confounding,” “masking,” and “excludability” (Butler & Homola, 2017; Hainmueller et al., 2014; Sher & McKenzie, 2006; Tomz & Weeks, 2013). The excludability assumption refers to the notion that the causal effect runs only through the treatment, and not some other factor (Angrist & Pischke, 2009). Similarly, information equivalence refers to the assumption that manipulating the variable of interest updates their beliefs about the given attribute, but not beliefs about the background characteristics (i.e., the treatment effect runs only through the manipulation). In other words, information equivalence in experimental vignettes corresponds to the exclusion restriction in instrumental variable analyses. This is particularly relevant for vignettes that rely on descriptive information to manipulate treatment, because descriptions of the treatment may signal information about the background characteristics of the subjects or context in the scenario (Butler & Homola, 2017). If based on the manipulation, respondents also update their beliefs about certain background attributes or characteristics that might influence the outcome (i.e., if information equivalence assumption is violated), then one cannot be certain that the manipulated treatment is the cause of subsequent changes in beliefs.

For example, experimental surveys that depict an interaction between police and a subject may manipulate factors related to the quality of treatment or characteristics of the outcome (e.g., Reisig et al., 2018). However, if not enough relevant information is provided in the scenario, it is possible that the respondent also updates their beliefs about certain background attributes that are likely to affect the measured outcome of perceived procedural justice. In this example, respondents may consider that high or low quality of treatment is determined by the subject’s demeanor or criminal background, officer characteristics or attitude, or the existing presence of a threat to officer or public safety, and as a consequence “impute” this information into the scenario. It may be then that subjects are responding to these background characteristics, and not to the treatment manipulation itself (Butler & Homola, 2017). Updating beliefs about these characteristics can lead to imbalance on background beliefs between respondents, potentially confounding the relationship between the treatment and outcome (e.g., see Metcalfe & Pickett, 2021). The unmeasured confound would instead drive variation in perceived procedural justice. Researchers can try to prevent this issue by instructing the respondent to imagine the scenario in abstract terms, including potential covariates fixed or varying within the scenario, and/or embedding a natural experiment within the scenario (i.e., the treatment is presented as randomly occurring, see Dafoe et al., 2018).

Finally, similar to field experiments, the effects of multiple treatments implemented in one survey experiment (e.g., procedural justice, distributive justice, context) are often tested independently, that is, ignoring interactions (Muralidharan et al., 2020). This can be problematic not only because it might overlook meaningful heterogeneity in effects, as demonstrated in procedural justice research (Piquero et al., 2004; Reisig et al., 2021; Sargeant et al., 2021; Solomon, 2019), but also because the “short” (direct effects only) model can provide inconsistent estimators of treatment effects if the value of the interaction is not zero (Muralidharan et al., 2020). Even so, experiments often do not have enough power to detect an interaction effect, meaning the absence of a significant effect does not necessarily indicate that there is no meaningful interaction (Gelman & Carlin, 2014).

Taken together, these issues present important challenges to the validity of vignette experiments depicting procedural justice treatments. Assessing the content of scenarios and summarizing effects can provide information on the external validity of procedural justice treatment effects on attitudes. Evaluating manipulations can tell us to what extent the treatments adequately reflect the different theoretical elements of procedural justice. Furthermore, while between-studies experimental vignettes benefit from randomization of treatment (if successful), this does not necessarily avoid threats to internal validity stemming from information equivalence. By reviewing studies in light of these issues, we can provide a critical overview of the potential limitations of causal evidence and gaps in knowledge for future experimental research on procedural justice and in criminology more broadly.

Methods

The current systematic review aims to document and assess experimental vignette studies that test some element of procedural justice theory. The protocol for this systematic review was pre-registered on the Open Science Framework on 7 March 2022, and last updated on 22 March 2022 [https://osf.io/fg84d], prior to full-text coding. Deviations from the protocol are noted below.

Criteria for inclusion

This review focused on studies that use between-subjects experimental survey designs (vignettes) to evaluate the effects of situational-related and treatment-related variables on perceptions of procedural justice and legitimacy. This means that studies were required to have any combination of one or more manipulated dimensions (e.g., 2 × 2, 2 × 3), and must have randomly assigned one of the vignette scenarios to each respondent. The vignette must manipulate at least some dimension of procedurally just treatment (e.g., respectfulness, fairness, voice, neutrality). This excluded within-individual and mixed designs. In order to be able to evaluate the content of the vignette, we focused here only on written descriptions of scenarios; thus, we excluded video vignettes.

Types of outcome measures

The focus of this review is to evaluate the effects of situational and process-based characteristics on attitudinal measures of procedural justice and legitimacy. We included both procedural justice and legitimacy-related attitudinal measures because it is plausible that studies may evaluate multiple theoretically relevant outcomes related to police-citizen interactions and procedurally just treatment. This included measures of specific and/or global procedural justice, trust, felt obligation to obey the police, and willingness to cooperate with the police. Behavioral measures, such as compliance with the police or the law, were excluded from this review.

Additional inclusion criteria

The timeframe covered spanned from 1970 to the date the primary search took place (March 2022). The language of the study is restricted to English.

Search methods

The search strategy proceeded in three stages:

-

1.

An initial search was performed using a single database (Web of Science) as well as the Journal of Experimental Criminology in order to refine the search strings. Titles and abstracts were reviewed in order to add or adjust keywords.

-

2.

The primary search was then conducted using the following keywords:

-

1.

((“polic*” OR “policing”) AND (“procedural* just*” OR “procedural* fair*” OR “fair proce*” OR “process-based” OR “procedural injustice”) AND (“vignette” OR “factorial” OR “factorial survey” OR “factorial survey experiment”) AND (“satisfaction” OR “trust” OR “confidence” OR “legitimacy” OR “cooperation”))

-

1.

-

3.

Google Scholar was used to supplement the search of primary databases and to scan the citation lists to identify any studies or grey literature that may have been missed.

Electronic databases

The primary search was conducted using four main electronic databases: Scopus, Web of Science, Sociological Abstracts, and EBSCO Host. A secondary search was conducted using Google Scholar.

Additional search strategies

In addition to Google Scholar, we scanned the reference lists from the selected studies as well as articles that have cited relevant studies. Any studies found during this stage were included in the full-text review.

Data collection and analysis

Study selection

Studies identified during the primary and secondary searches were imported into Zotero, where duplicates were removed. The first stage consisted of reviewing abstracts and titles based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined above. In the initial pre-registration, we planned to import all abstracts and titles into ASReview for screening. ASReview uses machine learning techniques to predict study relevance based on text and select the most relevant records for the reviewer (van de Schoot et al., 2021). However, the initial search produced only 51 documents total, resulting in 28 documents after de-duplication. Because this number was lower than expected, we changed our review strategy (updated in pre-registration on 10 March, 2022) so that two authors would review the titles and abstracts independently to mark for inclusion and exclusion based on the stated criteria. All papers marked as “maybe,” where it was not possible to make a decision based on the title and abstract, were included for full-text screening. In addition, because the number of papers meeting our search criteria was relatively low, we adapted our second stage full-text review strategy to also include two independent reviewers. Each reviewer assessed the eligibility for each study based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria stated above. Any uncertain cases were resolved through discussion between reviewers.

Coding scheme

Studies that met the eligibility criteria were coded based on the study characteristics, experimental design, key manipulations, the content of the vignette(s), manipulation or placebo checks, and analytical strategy. We also collected qualitative information on effects for each treatment variable (direction, significance). Studies were imported into NVivo for coding by one author. A random subsample (5%) of studies were coded by a second author. The final coding scheme can be found in the Supplementary information. In comparison to the preliminary coding scheme that was pre-registered, we made three adjustments to the coding categories. Namely, we (1) coded only the total sample size and did not code the sample size per condition, as the total sample plus number of factors was generally enough information. (2) We removed the coding category “Characteristics of the Interaction,” as it overlapped with the other vignette characteristics categories. And (3) we collected information only on the presence and significance of the interaction effect, as we were focused on documenting the main effects.

The focus of this review is to describe the use of vignettes in research on attitudes toward the police, including design and content, and assess the methodological quality of the designs and analytical strategies. Following coding, we analyzed the characteristics of the vignettes, including design and content, and methodological quality. Since a secondary goal of this review is to evaluate the evidence for situational factors that influence attitudes toward the police, we also present a narrative review of effects by situation, treatment, and outcome.

Results

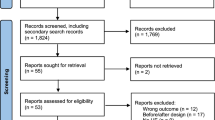

The initial search of databases identified 51 publications for possible inclusion. Figure 1 displays the search and inclusion/exclusion process in a PRISMA flowchart (Page et al., 2021). The removal of duplicates resulted in 28 publications for the first stage review. Titles and abstracts were screened, resulting in 17 publications for the second stage review (Cohen’s k = 0.78). Secondary Google Scholar and forward–backward searches found an additional 27 publications, resulting in a total of 44 publications eligible for full-text screening. The Cohen’s kappa at this stage was fair (k = 0.36). Cases of disagreement were discussed between coders until an agreement was made. At this stage, the main four reasons for exclusion were that the publication did not manipulate any dimensions of procedural justice (n = 13), did not contain a vignette (n = 3), had another version published elsewhere, for example a doctoral dissertation that published the study in a journal at a later date (n = 3), and measured the wrong outcome (n = 3). In one case, the interaction took place with an emergency operator instead of a police officer, and so there was some discussion between coders as to whether this fit the inclusion criteria. The scenario described an interaction between a subject calling for police services and the quality of treatment by the operator (Flippin et al., 2019). Given the close connection with the police in the scenario, and that the design measured subsequent attitudes toward the police, we ultimately opted to include the study in the review.

The final sample included 20 publications containing 20 independent studies. Within the 20 independent studies, 23 unique vignette scenarios were fielded. Three publications evaluated the same vignette scenario using the same dataset, which are treated as one study for purposes of analyzing the design and characteristics of vignettes (McLean, 2020, 2021; Wolfe & McLean, 2021). One publication assessed effects on procedural justice and related attitudes (McLean, 2020), one assessed effects on procedural justice and “justice-restoring responses” (McLean, 2021), and the third publication examined the relationship between national identity and police legitimacy, but included the manipulations from the vignette scenario as independent variables (Wolfe & McLean, 2021). Since justice-restoring responses do not align with the original outcome inclusion criteria, we focus on the results for procedural justice in the latter publication. Additionally, given that the first two evaluate procedural justice outcomes, we treat them as one in our analyses of substantive results. The third publication contains a different outcome (police legitimacy) and so this publication is treated separately in our analyses of results. One publication, a doctoral dissertation, contained two vignette studies conducted among different samples (Trinkner, 2012). The second dissertation vignette study was published separately (Trinkner & Cohn, 2014), and so for the analyses we include the first unpublished dissertation study and the published version of the second study. Since the vignette used in both studies was the same, we treat these studies as one when analyzing the vignette characteristics.Footnote 1

Characteristics of the included studies

Of the 20 publications, five were unpublished thesis manuscripts, one was a book chapter, and the remaining 14 were published in peer-reviewed journals. Out of the 20 independent studies, the vast majority were fielded in the USA (n = 15). The remaining studies were conducted in Australia (n = 3) and Ghana (n = 2).

Methodological characteristics

Research design

All studies evaluated some dimensions of procedural justice, as well as other situational or actor-related characteristics. The majority of studies applied a 2 × 2 factorial design (n = 10), whereby two factors were manipulated on two dimensions. For example, McLean (2020, 2021) manipulated both procedural justice (just, unjust) and outcome favorability (ticket, no ticket). Three studies manipulated two factors within a single vignette scenario, and included two separate vignette scenarios as an additional (non-randomized) third factor (e.g., hit-and-run witness vs. stalking victim), resulting in a 2 × 2 × 2 design (Brown & Reisig, 2019; Flippin et al., 2019; Reisig et al., 2018). An overview of study characteristics and design is available in Table 1.

Studies adopted multiple analytical approaches to evaluate direct effects of the manipulations on various outcomes. The majority of studies used some form of linear or ordinal regression (n = 14), as well as more straightforward t-tests and ANOVAs (n = 5). Several studies aimed to evaluate mediation processes connecting vignette treatments, attitudes, and other outcomes, and so employed structural equation modeling techniques to test these pathways (n = 4). In the current study, we focus on summarizing direct effects of treatments on attitudinal outcomes, and so we will evaluate only the direct effects within these regression or path models.

Sample characteristics

The size of the sample for the included studies ranged from (approximately) n = 130 to n = 2296. The average sample size was n = 567. Notably, all studies employed some form of non-probability sampling, with half drawing only on university convenience samples (n = 10). Four of which drew on undergraduate students at Arizona State University, although two refer to a university in the “southwestern USA” (Brown & Reisig, 2019; Flippin et al., 2019; Reisig et al., 2018; Stanek, 2017). These surveys took place in 2016, 2017, and 2018 among both lower-level and upper-level courses. Three surveys sampled criminal justice students specifically. This means that it is possible that some of the students may have participated in multiple studies. Two studies included samples drawn from police samples (local or online) (Hazen, 2021; Hazen & Brank, 2022). Two studies drew non-probability quota or purposive samples from selected neighborhoods in Ghana (Nivette & Akoensi, 2019; Tankebe, 2021), two from a selection of grade schools in New Hampshire, USA (Jeleniewski, 2014; Trinkner & Cohn, 2014), and one from a sample of Muslims in Sydney, Australia (Madon et al., 2022). Five studies used online, crowdsourced samples from Qualtrics or Mechanical Turk (MTurk).

In light of a reviewer’s comment, we also coded which studies conducted a priori power analyses to inform the necessary sample size for their data collection and analyses. Only two studies reported conducting a priori power analyses (Hazen, 2021; Hazen & Brank, 2022).Footnote 2

Vignette characteristics

The 23 different vignette scenarios depict a range of police-citizen interactions, with varying types of contact, situational or background characteristics, and actor characteristics (see Table 2). Eleven out of the 23 scenarios described citizen-initiated contacts, of which three were witnesses to a crime or incident (i.e., hit and run accident and a mental health crisis), five were victims of various crimes (i.e., stalking, burglary, theft, sexual assault), and two were routine (i.e., applying for a permit). One scenario depicted a citizen-initiated provocation, wherein a man aggressively approaches a police officer on the street (Silver, 2020). The remaining 12 scenarios describe police-initiated encounters, of which eight portrayed police interacting with potential suspects or individuals who have broken a rule (i.e., searching for a suspect, questioning potential truants, stopping people for potential violation of a traffic rule or social distancing/lockdown measures, attending a noise complaint). In three of the 12 scenarios, police are engaged in routine interactions (i.e., police traffic control, breath tests).

The 23 scenarios share few similar background characteristics, as they describe a wide range of situations, actors, and contexts. However, there are some common themes among the background contexts, notably among studies that share one or more of the same authors. For example, Sivasubramaniam et al. (2021) designed two scenarios within a similar context (i.e., random breath tests) that would be comparable in the US and Australian context. The scenarios included in Brown and Reisig (2019) and Flippin et al. (2019) also depict similar types of experiences (i.e., calling the police to report an incident) but differing contexts and crimes: The former describes interactions with the police, while the latter describes interactions with the emergency (911) operator.

In 14 out of the 23 scenarios, the participant is encouraged to imagine themselves as the focal subject in the scenario (“You”). The remaining nine scenarios specify that a male is the focal character, of which three additionally specify the male character’s (approximate) age (i.e., teenager, 20 years old, and 43 years old). Few provide any further information about other characteristics (e.g., college student, aspiring musician) or other actors involved (e.g., group of teenagers, partygoers). Only one provides the ethnicity of the subject (i.e., Muslim, Madon et al., 2022). The most common characteristic provided for the officer was gender, with 18 out of 23 scenarios providing this information. In four of those scenarios, the officer’s gender was manipulated (male or female). The remaining 14 scenarios depicted a male officer. Often this information was provided through context clues, such as using “he said” after dialog (e.g., Sharma, 2017). Five scenarios did not provide information or any context clues to determine the gender of the officer. Three scenarios provided the police department that the officer represented (i.e., Victoria Police in Australia, Chicago Police in the USA). Only one scenario provided further information, including the ethnicity of the officer: Officer Armstrong, a white male, about 170 pounds, fit, mid-30s, and in uniform (Sivasubramaniam et al., 2021).

Manipulations

A sample of the procedural justice manipulations within each scenario are presented in Table 3. Here we presented only a snippet of some manipulations, as they were sometimes several lines long. The elements included are based on what the authors’ claimed when describing the scenarios, or in the absence of this description, based on our own interpretation of the manipulations. The full scenarios and manipulations are available in the Supplementary information. Procedural justice was operationalized in a number of ways, including various combinations of quality of treatment (respect, trustworthy motives) and decision-making (neutrality, voice). As Table 3 shows, all but three scenarios manipulated elements of respectful treatment (n = 20), whereby 16 scenarios arguably manipulated voice as well. Just under half of the scenarios manipulated neutrality (n = 8) and/or trustworthy motives (n = 10).

Looking closer at the text of the manipulations, there are a few patterns that emerge. First, disrespectfulness is often operationalized as the officer acting in a rude manner, using profanity, and directly insulting the subject. In one scenario, the officer responding to someone reporting a potential stalker says that “unless you [the subject] are blind as a bat you can see they’re [the stalker] just walking on the sidewalk.” Another scenario has the emergency operator yelling at the subject saying, “Knock it off!” and says if they are going to “act like a baby” they can wait outside for the police. In one scenario, the officer yells at the subject that the subject is “going to kill somebody” and that they “don’t want to hear whatever lame ass excuse” the subject has. Officers in the scenarios variously call subjects stupid, “asshole,” or “jack ass,” tell them to shut up, call their music “shitty,” and accuse them of being criminals or a terrorist. By contrast, the respectful conditions often describe officers using a “pleasant tone,” calling the subject “Sir” (there are no named female subjects), saying “hi,” and saying “thank you” or “sorry to trouble you” at the end of the encounter. In some scenarios, the vignettes describe the quality of treatment directly, instead of describing through actions or dialog (e.g., “You feel the officer treats you with respect” or “the officer…shows concern and respect”).

The contrast between the two respect conditions is high, and one can argue that many of the disrespect manipulations are relatively extreme in comparison to the respect manipulations. None of the scenarios included a “neutral” or “business-as-usual” manipulation, wherein the officer would give a command or dialog without using pleasantries or alternatively foul language. Three studies included “control” manipulations in contrast to procedural injustice manipulations (Brown & Reisig, 2019; Flippin et al., 2019; Reisig et al., 2018); however, the officers in these control scenarios still treat the subject with respect and provide opportunities for voice (e.g., they say please and thank you, appreciate the subject’s input, and listen to their story).

The second notable pattern across manipulations was that multiple elements of procedural justice were often varied together as a single treatment (e.g., either procedurally just or procedurally unjust). Few studies manipulated only one element (i.e., only respect, only voice), and only two manipulated different elements separately (i.e., voice and neutrality).

Finally, some manipulations, and scenarios more generally, were quite lengthy and complex compared to others. The scenario describing a mental health crisis is nearly 1000 words in length, involving three manipulations which are embedded in multiple different parts of the vignette (Jones et al., 2021). Likewise, the random breath test and social distancing scenarios are of a similar length and complexity (Sivasubramaniam et al., 2021). By contrast, others are relatively short (around 200 words).

Manipulation checks

The majority of studies reported that they conducted manipulation checks (n = 16 out of 20 studies), which typically followed immediately after the respondent read sometime after the scenario. In five studies, it was not clear exactly when the manipulation checks were presented. In eight of the studies, we could deduce that the manipulation checks followed directly after the scenario. In three of the studies, the manipulation checks followed after the dependent variables. However, the type of manipulation check was not always the same across studies, as some reported conducting checks on attention (e.g., Brown & Reisig, 2019), which assess to what extent the respondent had thoroughly read and understood the scenario, while others reported conducting checks on meaning and treatment effectiveness (e.g., Nivette & Akoensi, 2019; Reisig et al., 2018). Some of the studies excluded participants that did not pass attention checks (Brown & Reisig, 2019; Flippin et al., 2019; Sivasubramaniam et al., 2021; Trinkner & Cohn, 2014), while others explicitly did not (Jones et al., 2021). In one study, it was reported that participants failing attention checks were removed prior to randomization (McLean, 2021).

Information equivalence

Generally, studies included in the current review did not discuss issues related to information equivalence, although some took steps to consider potential threats to internal validity. None of the studies in the sample reported using abstract encouragement as a tool to discourage respondents from applying real-life data to update their beliefs and reduce imbalances (Dafoe et al., 2018). In some studies, respondents were encouraged to consider the scenario as realistically as possible. As mentioned above, a number of studies explicitly described the subject in the scenario as “You” (the participant). Six out of the 20 studies conducted covariate balance tests on a range of background characteristics (e.g., demographics, prior trust in police). Most of these studies found no imbalances on the given covariates, and therefore did not include them in the primary analysis of treatment effects (e.g., Reisig et al., 2018). Interestingly, although six studies explicitly conducted balance checks, a further eleven studies included covariate controls in the primary analyses, or as a robustness check. Only three studies explicitly discussed fixing a particular covariate in the scenario (Jeleniewski, 2014; Trinkner, 2012; Trinkner & Cohn, 2014). The fixed covariates were the sex of the actor and officer (both male). None of the studies incorporated a natural experiment into the vignette scenario. Furthermore, none of the studies conducted placebo checks to evaluate to what extent the experimental treatment operates solely through the intended causal pathway.

Summary of effects

Within the current sample of studies, a total of 108 main treatment effects were tested on a range of attitudinal outcomes about the police. One study did not report direct treatment effects (Hellwege et al., 2022). Here we focus on the main effects of procedural justice and sub-dimensions of procedural justice on attitudinal outcomes related to police legitimacy and procedural justice.Footnote 3 The results in Table 4 show that the vast majority of procedural justice treatment effects are significantly related to more positive attitudes and judgments about the police. First, it is important to note that the outcomes vary substantially across studies, including more specific measures of procedural justice elements such as voice, fairness, and neutrality, as well as broader measures of trust, procedural justice, satisfaction, and police legitimacy. The treatment effects for overall procedural justice (i.e., different elements combined into one treatment) appear to be associated with attitudes consistently across different outcome measures. However, the treatment effects for different elements of procedural justice are more mixed. The effects of respect were associated with measures of procedural justice, satisfaction, and cooperation, whereas the effects of voice and neutrality were inconsistently related to measures of police legitimacy and perceptions of fairness, trust, and respect. In two cases, the effects of voice were associated with more negative perceptions of neutrality and respect (Hazen & Brank, 2022). Regarding interaction effects, 12 out of the 19 studies that included more than one factor evaluated (formally or informally) interactions between treatment effects.

Discussion

The current systematic review aimed to describe and critically assess the use of experimental vignettes in procedural justice research, with attention to broader implications in criminology. We outline five findings related to sample composition and generalizability, characteristics of the vignette and treatment manipulations, analyzing treatment effects, checking assumptions and manipulations, and substantive results of procedural justice on attitudinal outcomes.

First, our sample of studies consisted entirely of non-probability samples, of which over half were convenience samples drawn from university student (and often criminal justice student) populations. This means that the substantive results cannot be generalized beyond the particular student samples. Notably, five studies used crowdsourced samples drawn from MTurk or Qualtrics (see Table 1). While these samples tend to be more diverse, and to some extent more representative than traditional convenience samples (Berinsky et al., 2012), studies in the USA found that they are still not nationally representative and that they differ on important demographic and individual characteristics (Chandler & Shapiro, 2016; Weigold & Weigold, 2021). Thus, while crowdsourced samples have advantages over the typical university convenience sample, they are still limited in drawing generalizable conclusions about theoretical mechanisms. More broadly, the general use of university convenience samples, and the re-use of the same sample, suggests that the research landscape testing procedural justice using vignettes is still relatively limited. The majority of the studies in the current sample were also conducted in the USA, meaning we need more representative samples from different countries to further test the theory across different institutional and social contexts. It remains an open question whether and to what extent the effects of police-citizen interactions can be compared and replicated across diverse historical and institutional contexts of policing.

Second, the scenarios themselves depicted a wide range of contexts (i.e., citizen-initiated and police-initiated), subject roles (e.g., victim, witness, suspect), and background contexts (e.g., calling the police, encountering routine stops). Furthermore, both actor and officer characteristics were largely described as male, except where experimentally manipulated and/or the subject was the participant (i.e., “you”). On the one hand, given the consistency in associations between procedural justice manipulations and attitudinal outcomes (see Table 4), one can argue that background and actor characteristics do not matter as much as how the officer treats the subject within any given scenario. The studies that manipulated officer gender and tested direct effects found no differences in subsequent attitudes (Brown & Reisig, 2019; Stanek, 2017). On the other hand, other characteristics that could condition treatment effects or directly influence attitudes were not controlled for within most scenarios. For example, studies using video vignettes (not included in the current review) that have manipulated driver ethnicity found that the relationship between procedural justice and encounter-specific outcomes depends on the ethnicity of the subject in the vignettes (Johnson et al., 2017; Solomon, 2019). Without this information provided in the vignette, respondents may make assumptions about the ethnicity of the subject(s) and officer(s) involved and update their perceptions accordingly.

In addition, the use of “you” in the scenario might introduce similar issues if the interpretation depends on certain characteristics of the respondent (e.g., ethnicity, gender, criminal history). Technically, the use of “you” in an experimental vignette can be considered a violation of the Stable Unit Treatment Value Assumption (SUTVA). SUTVA states that (1) the potential outcome of one unit being assigned treatment should not affect the potential outcome of other units, i.e., there should be no treatment spillover or no interdependence between units, and (2) treatment should mean the same for each unit being assigned treatment (Cunningham, 2021). Employing “you” in a vignette creates non-observable heterogeneity in treatment effects, as there might be very different “versions” of treatment levels unknown to the researcher, resulting in different potential outcomes. This potential confounding threatens internal validity, limiting conclusions about the causal effects of procedurally just treatment on attitudes. More research is needed to examine to what extent background, subject, and situation-specific characteristics potentially confound or even directly relate to subsequent attitudes toward the police. This can be accomplished by including a range of experimentally manipulated controls for theoretically relevant characteristics within the scenario (Dafoe et al., 2018; Metcalfe & Pickett, 2021). This approach allows one to examine the independent effect of these characteristics, as well as to what extent they may account for or confound the main treatment effect.

However, it is important to balance the need for specifying additional information with the length and complexity of the vignette itself. Another incidental finding of this review is that the structure of the vignette scenario varied across studies, with some that were relatively short (~ 200 words) and others that were substantially longer (~ 1000 words). A very short vignette may be limited as it might omit relevant details important to the realism of the scenario and/or incorporating fixed covariates or an embedded natural experiment. Research on survey design has shown that the length and complexity of an instrument can generate respondent fatigue and satisficing, leading to biased responses (Kreps & Roblin, 2019; Roberts et al., 2019). In survey methodology, satisficing “refers to the expenditure of minimum effort to generate a satisfactory response, compared with expending a great deal of effort to generate a ‘maximally valid response’” (Roberts et al., 2019: 601). A long, complex scenario may result in the respondent choosing to skim the reading and exert minimum effort in selecting responses, introducing measurement error. While narrative checks can to some extent detect satisficing if the respondent answers incorrectly or does not differentiate their answers, this can also introduce other biases as discussed below. Some of the studies in the sample that conducted these checks subsequently dropped participants that did not pass. However, there are strong arguments not to drop these participants from the analyses, as this can introduce bias in estimation or asymmetry in treatment (Aronow et al., 2019; Jones et al., 2021; Montgomery et al., 2018). To avoid these issues, an attention check included prior to the scenario can be used to increase focus and more careful responses among participants (Hauser et al., 2018).

Another explanation for the consistent effects of procedural justice may be how they were designed and evaluated. The vast majority of procedural justice manipulations depict officer behavior at positive and negative extremes. In particular, the officers in the negative manipulations were typically rude, belligerent, and insulting, whereas the officers in the positive scenario were polite and accommodating. These extreme manipulations are reflected in the very large effect sizes. For example, one study found that the effect of procedural (in)justice was negatively associated with police legitimacy (b = − 1.57). This is equivalent to a standardized effect size of β = − 0.78, or Cohen’s d = − 2.54 (Brown & Reisig, 2019).Footnote 4 Another study reported effect sizes of β = 0.80, 0.95, and 0.71 (Cohen’s d = 2.62, 6.54, 2.03) for officer respect on procedural justice (studies 1, 2, and 3 respectively, Sivasubramaniam et al., 2021). To compare, the observed effect of procedural justice treatment on specific procedural justice in the Queensland Community Engagement Trial was d = 0.34 (Mazerolle et al., 2012) and the mean effect of procedural justice treatments in interventions was estimated as OR = 1.47 (d = 0.21) (Mazerolle et al., 2013a, 2013b). A review of effect sizes in criminological research reported that the average effect was r = 0.148 (d = 0.30) (Barnes et al., 2020). This suggests that the effect sizes reported in these vignette studies are unusually large in relation to other studies in the field.

Such strong manipulations present two possible issues for the validity of these manipulations and results. First, strong and overt one-off treatments may not reflect real-world situations where subjects can be exposed to more frequent, weaker stimuli (Gaines et al., 2007). For example, someone may be subject to repeated stops by police over a longer period of time. The police may act relatively polite or even neutral during each encounter, but it is the cumulative low-level exposure that erodes trust and legitimacy in the police (Bell, 2017; Haller et al., 2020; Nagin & Telep, 2017; Oberwittler & Roché, 2018). Second, including only two extremes does not tell us about the effect of procedural justice relative to a control condition, or sometimes called “business as usual.” Policing researchers are increasingly assessing the potential for “asymmetric effects” in citizen-officer encounters and treatments (Choi, 2021; Maguire et al., 2017; Thompson & Pickett, 2021). Studies that have included positive, negative, and neutral/mixed procedural justice treatment found that the size of the effect of negative treatment was significantly larger compared to positive treatment (Choi, 2021; Johnson et al., 2017). Additionally, these asymmetric effects may be more pronounced for global outcomes compared to encounter-specific outcomes (Maguire et al., 2017). Overall, the lack of control group and more nuanced variation in treatment makes it difficult to determine to what extent effects are driven by respectful or disrespectful treatment (or both). Ideally, scenarios should include manipulations depicting a gradient of (dis)respectful treatment in order to adequately test the size of “good” versus “bad” treatments in comparison to a control or “business-as-usual” group.

Relatedly, the manipulations often contained multiple elements of procedural justice (i.e., quality of treatment and decision-making). In studies that manipulated single dimensions separately (e.g., voice, neutrality), the summary effects were more mixed (Hazen & Brank, 2022; Trinkner, 2012). The inclusion of multiple treatments in one condition makes it impossible to determine which element (quality of treatment or decision-making) is driving the effect on subsequent judgments. Research using video vignettes that included separate manipulations for respect (treatment) and voice and neutrality (decision-making) found that each element had differential effects on subsequent attitudes toward the police (Solomon, 2019; Solomon & Chenane, 2021). More specifically, in both publications, treatment quality (respect vs. disrespect) had a relatively stronger effect on subsequent perceptions of fairness, distributive justice, cooperation, and trust.

Third, we found that studies in our sample analyzed treatment effects using various designs and analytical techniques, including ANOVA, OLS or ordinal regression, and structural equation modeling. Twelve of the studies tested in some way for interaction effects between multiple treatments. In some cases, this was done descriptively using for example bar graphs, while in others this was tested by including an interaction term in the model. Only three of these formal tests were significant. It is important to note that incorporating multiple treatments in one scenario and testing main effects independently might lead to biased estimates of effect if the value of the interaction is not zero (Muralidharan et al., 2020). Muralidharan and colleagues argue that the focus on significance of the interaction term can be misleading, because factorial designs are often underpowered in detecting an effect. Only two studies reported conducting a priori power analyses to inform data collection; however, these were ostensibly focused on power to detect main treatment effects (Hazen, 2021; Hazen & Brank, 2022). If one wishes to detect the size of the treatment effect of procedural justice reported in Mazerolle et al.’s systematic review (d = 0.30), the necessary sample size per group would be n = 176, n = 352 total for a single factor (80% power, alpha = 0.05).Footnote 5 Five studies in our sample report a total sample size less than n = 352. The sample needed to detect significant interaction effects is larger than what is needed to detect main effects (Gelman & Carlin, 2014). Conducting power analyses for interaction effects can be challenging, as it requires researchers to consider the expected size and type of the interaction (i.e., ordinal vs. crossover); however, statistical software packages are available to guide researchers in estimating power for interactions (Lakens & Caldwell, 2021). As such, if researchers are interested in testing interactions between treatments, which is plausible in procedural justice theory and research (Johnson et al., 2017; Jones et al., 2021; Nivette & Akoensi, 2019; Solomon, 2019), power analyses to detect an interaction effect should be reported in the pre-registration or pre-analysis plan (Gelman & Carlin, 2014; Muralidharan et al., 2020).

Fourth, most studies conducted manipulation or narrative checks following the reading of the scenario, and some evaluated to what extent respondents were balanced on background characteristics across treatments. While no studies explicitly evaluated the information equivalence assumption, these issues were only recently reignited in political science and criminology (Dafoe et al., 2018; Metcalfe & Pickett, 2021). While researchers exploiting random variation in observational data need to defend the exclusion restriction of potential other treatment channels (Angrist et al., 1996), “survey experimentalists” need to employ similar methods to ensure that the information equivalence assumption holds (Dafoe et al., 2018). Failing to conduct tests of balance on background beliefs across experimental groups reduces confidence in whether the effect of interest is identified. Placebo tests are used in observational studies to evaluate their identification strategy, which assumes that the effect of the treatment only operates through the treatment variable (e.g., quality of treatment or decision-making). An ideal placebo attribute should not be affected by the treatment (e.g., often factors that occurred before treatment, or are relatively stable characteristics), should be correlated with the treatment in the real world, and plausibly affect the outcome (Dafoe et al., 2018). In relation to procedural justice and police-citizen interactions, this could be the subject’s criminal history, history with the police, ethnicity, conduct prior to interaction, the events leading up to the interaction, the officer’s prior conduct or reputation, the reputation of the police agency, or other relevant factors that are not determined by the manipulation (treatment) itself. Researchers can aim to prevent these imbalances by including relevant placebo attributes as either fixed covariates or additional manipulations in the scenario. As manipulations, the placebo attributes can then be included in subsequent analyses to reduce or control for imbalances, similar to covariate adjustment used in observational studies (Dafoe et al., 2018). These imbalances should also be explicitly tested by including follow-up questions (placebo tests) that ask respondents about their beliefs regarding the background attributes of the subject and/or police as they may have been prior to the scenario occurring (pre-treatment). One can then evaluate to what extent respondents did in fact update their beliefs (or not) about these attributes, and whether these background beliefs likewise influence the outcome.

An embedded natural experiment can ensure that the respondent believes that the treatment is randomly assigned, and so they are less likely to rely on their prior beliefs about how the treatment is allocated in the real world (Dafoe et al., 2018). In contexts of policing, treatment assignment in the real world is notably non-random, and can be perceived to be distributed and biased depending on certain situational, subject, and officer characteristics (Braga et al., 2019; Carmichael et al., 2021; Mastrofski et al., 2016; Radburn et al., 2022). Embedding a natural experiment into a scenario about policing is more challenging, and in many cases impossible, but there are real-life examples that the scenario can be modeled on, for example describing unexpected changes in policing tactics brought on by sudden layoffs (Piza & Chillar, 2021) or an exogenous threat (Jonathan-Zamir & Weisburd, 2013). This may be more plausible when considering the distribution of treatment rather than the quality of treatment, as there are real-life events that can lead to unexpected changes in police presence or patrol, such as in the examples above. The main goal of embedding a natural experiment is to convince the reader that the events in the scenario lead to as-good-as-random assignment to treatment.

As discussed above, given the lack of fixed or controlled covariates in most scenarios, and the lack of evaluation of information equivalence, we cannot be certain to what extent the procedural justice treatments in the sample studies have a causal effect on attitudes. Future studies should carefully consider theoretically relevant covariates to fix or control and conduct placebo checks on potential confounds to evaluate the information equivalence assumption. If possible, an embedded natural experiment in the scenario can also help to reduce the possibility of confounding.

On a related note, the manipulation or narrative checks conducted within studies often followed directly after the respondent read the vignette scenario. While manipulation checks are important for evaluating whether the treatment had the intended effect, there are downsides to utilizing manipulation checks within the main study. In particular, manipulation check questions that follow immediately after the scenario can provide clues to the respondent as to the researcher’s hypotheses and it can for example enhance the manipulation by crystallizing feelings (Hauser et al., 2018). This means that the inclusion of manipulation checks in the main study could bias the dependent variable. Similarly, manipulation checks that are measured after the dependent variable may be influenced by their response to the dependent variable items. If manipulation checks are presented at the end of the study, long after the respondent has read the scenario, they may forget relevant details about the manipulations. In order to avoid these issues, some recommend that manipulation checks should be conducted in a pilot study among the same population prior to the main study (Ejelöv & Luke, 2020; Hauser et al., 2018). The pilot study should be conducted in a reasonably short time frame prior to the main study, should have appropriate power to detect the desired effects, and should evaluate the construct validity of the manipulation’s dependent variable (Chester & Lasko, 2021; Ejelöv & Luke, 2020). In addition, Ejelöv and Luke (2020) argue that researchers should consider not only the significance of the manipulation checks (e.g., procedural justice on perceptions of respectful treatment), but also the size of the effect. If a manipulation requires a certain level of change, for example that the police are being either mildly or extremely disrespectful, then some attention must be paid to the strength of the manipulation. A pilot study can help researchers test the strength of these effects, and make relevant calibrations for the main study if necessary.

Finally, as mentioned above, the substantive results show that combined procedural justice manipulations are associated with a variety of relevant attitudinal outcomes, including perceptions of legitimacy, normative alignment, trust, satisfaction, and willingness to cooperate. However, given the more widespread use of manipulation checks, it is difficult to separate manipulation effects (did the treatment work) from substantive effects (did the treatment affect attitudes). The combination of different procedural justice elements into one manipulation makes it difficult to determine which mechanism is driving the effect. Given the rather overt and sometimes extreme “disrespect” elements included in the manipulations, it is possible that these substantive effects are driven by differences in respectful treatment (Solomon & Chenane, 2021). In addition, the outcomes and measurement of outcomes varied widely across studies, limiting overall conclusions about a particular attitudinal outcome. Future research that aims to test procedural justice theory should not only disaggregate different elements of procedural justice in the scenario, but also consistently measure the relevant theoretical mechanisms within the model (e.g., trust, moral alignment, obligation to obey, cooperation with police).

In order to summarize the main findings, we highlight six points for researchers to consider when conducting between-person experimental vignettes. These points are relevant for both policing researchers interested in testing procedural justice theory, as well as criminologists more generally.

-

1.

Specify and evaluate theoretical components separately where relevant. In relation to procedural justice theory, different elements of procedural justice (e.g., voice, respect) should be disaggregated in manipulations to more precisely test relative effects on attitudes.

-

2.

Manipulations should include a (neutral) control condition or reflect a gradient of the attribute.

-

3.

Prevent potential violations of the equivalence assumption by incorporating potential confounders or embedding a natural experiment into the design. Potential confounders can be incorporated by either fixing relevant characteristics (i.e., by describing them in the vignette) or including them as separate manipulations and covariates in the model (see e.g., Metcalfe & Pickett, 2021).

-

4.

Formally assess potential violations of the equivalence assumption by running placebo checks on relevant background attributes. This increases confidence that the causal treatment effect flows from the manipulation and not some unobserved confounding pathway.

-

5.

Manipulation checks should be conducted in a separate suitably powered study that is fielded prior to the main study.

-

6.

Researchers should ensure they have suitable power to detect significant main and interaction effects by conducting a priori power analyses (Gelman & Carlin, 2014).

Limitations

While the current review covers a wide range of scenarios and experimental manipulations related to procedural justice, there are important limitations. First, this review included only text-based vignettes, excluding studies that have used video vignettes to manipulate police-citizen interactions (e.g., Solomon, 2019). Video vignettes can have certain advantages over text-based vignettes, including realism and incorporating more fixed covariates as they can be visually observed by the respondent. However, video vignettes are not always feasible, nor do they easily allow for multiple (covariate) manipulations or more controversial police behaviors. Nevertheless, the principles of survey, scenario, and experimental design covered in this review also apply to evaluating video vignettes. Further research should collect and systematically assess the content of video vignettes used in procedural justice research in order to draw conclusions about methodological characteristics and substantive effects on attitudinal outcomes.

The current review also took a narrative approach to summarizing effect sizes due to the variation in operationalizations, designs, and outcomes across studies. This means that we were not able to estimate a summary effect size, or statistically examine heterogeneity in effects. Future research aiming to quantitatively summarize effects must carefully consider how studies operationalize elements of procedural justice in order to ensure comparability across treatments.

Another limitation of the current review is that we focused solely on between-subjects design, whereas factorial survey experiments may also take on within-subjects or mixed-subjects design. Our choice to focus on between-subjects design was driven by the wide use of this type of design within criminology, and particularly procedural justice research. In a within-subjects design for example, respondents are provided the same population of vignettes with variation across different theoretical dimensions (e.g., police or subject characteristics, quality of treatment, decision-making, use of force, outcome) (Wallander, 2009). However, alternative designs, such as within-person designs, can answer different questions about what elements of police behavior and treatment do respondents judge to be fair or trustworthy. To our knowledge, only one study has used this type of design within police procedural justice research (Van Petegem et al., 2021), which can perhaps help disentangle the effects of different elements of treatment and decision-making on public judgments about police.

Conclusions

Experimental vignettes are advantageous in evaluating how different theoretical or contextual factors can influence public attitudes as they have been shown to approximate real-world responses and behaviors (Hainmueller et al., 2015). This means that vignettes can more rigorously test the principles of procedural justice and advance our understanding of public attitudes toward the police. However, there are a number of potential pitfalls in designing vignettes from which causal inferences can be made. Based on our review, we recommend that future studies using text-based vignettes disaggregate different elements of procedural justice in manipulations, and include a gradient of treatment or behavior (including control) to avoid comparing extremes and to incorporate potential confounders as either fixed covariates or manipulations. Researchers should evaluate potential violations of the information equivalence assumption, including conducting balance tests, controlling for potential confounds, and running placebo checks on relevant background attributes. In addition, to avoid biasing the dependent variable, manipulation checks should be conducted in a separate suitably powered pilot study prior to the main study. Taken together, these suggestions can inform future research to develop and evaluate vignette studies that can more precisely estimate the effects of procedural justice treatment(s) on perceptions of police.

Notes

All coded materials used to derive the findings and construct the tables are available online [https://osf.io/4db6z/].

We note that the use of the power analysis is not always clear. Hazen and Brank (2022) report that their power analysis using G*Power showed that they would need a total sample of n = 70 in order to achieve an 80% chance of detecting a small (r = .20) effect using linear regression with 5 predictors (pg. 159). However, upon attempting to replicate this analysis, it appears that the test used in G*Power was to detect an R2 deviation from zero. When we conducted an a priori analysis in G*Power to detect an effect of r = .20 (d = .40) using differences between two independent means (two groups), the necessary sample size was n = 100 per group.

The full list of treatment effects for each outcome is available online [https://osf.io/4db6z/].

Calculated in G*Power using t-test family category and “means: difference between two independent means (two groups),” 80% power, alpha = 0.05, two-tailed test, allocation N1/N2 = 1.

References

*Included in systematic review

Aguinis, H., & Bradley, K. J. (2014). Best practice recommendations for designing and implementing experimental vignette methodology studies. Organizational Research Methods, 17(4), 351–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114547952

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J. S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press.

Angrist, J. D., Imbens, G. W., & Rubin, D. B. (1996). Identification of causal effects using instrumental variables. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 91(434), 444–455. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1996.10476902

Aronow, P. M., Baron, J., & Pinson, L. (2019). A note on dropping experimental subjects who fail a manipulation check. Political Analysis, 27(4), 572–589. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2019.5

Atzmüller, C., & Steiner, P. M. (2010). Experimental vignette studies in survey research. Methodology, 6(3), 128–138. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-2241/a000014

Auspurg, K., & Hinz, T. (2015). Factorial survey experiments. Sage.

Barnes, J. C., TenEyck, M. F., Pratt, T. C., & Cullen, F. T. (2020). How powerful is the evidence in criminology? On whether we should fear a coming crisis of confidence. Justice Quarterly, 37(3), 383–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2018.1495252

Bell, M. C. (2017). Police reform and the dismantling of legal estrangement. The Yale Law Journal, 126(7), 2054–2150.

Berinsky, A. J., Huber, G. A., & Lenz, G. S. (2012). Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk. Political Analysis, 20(3), 351–368. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpr057

Bradford, B., Murphy, K., & Jackson, J. (2014). Officers as mirrors: Policing, procedural justice and the (re)production of social identity. British Journal of Criminology, 54(4), 527–550. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azu021

Braga, A. A., Brunson, R. K., & Drakulich, K. M. (2019). Race, place, and effective policing. Annual Review of Sociology, 45(1), 535–555. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073018-022541

*Brown, K. L., & Reisig, M. D. (2019). Procedural injustice, police legitimacy, and officer gender: A vignette‐based test of the invariance thesis. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 37(6), 696–710. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2439

Butler, D. M., & Homola, J. (2017). An empirical justification for the use of racially distinctive names to signal race in experiments. Political Analysis, 25(1), 122–130. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2016.15

Carmichael, J., David, J.-D., Helou, A.-M., & Pereira, C. (2021). Determinants of citizens’ perceptions of police behavior during traffic and pedestrian stops. Criminal Justice Review, 46(1), 99–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734016820952523

Chandler, J., & Shapiro, D. (2016). Conducting clinical research using crowdsourced convenience samples. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12(1), 53–81. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093623

Chester, D. S., & Lasko, E. N. (2021). Construct validation of experimental manipulations in social psychology: Current practices and recommendations for the future. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(1), 377–395.

Choi, J. (2021). Asymmetry in media effects on perceptions of police: An analysis using a within-subjects design experiment. Police Practice and Research, 22(1), 557–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2020.1749624

Cunningham, S. (2021). Causal inference: The Mixtape. Yale University Press.

Dafoe, A., Zhang, B., & Caughey, D. (2018). Information equivalence in survey experiments. Political Analysis, 26(4), 399–416. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2018.9

Ejelöv, E., & Luke, T. J. (2020). “Rarely safe to assume”: Evaluating the use and interpretation of manipulation checks in experimental social psychology. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 87, 103937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2019.103937

Findley, M. G., Kikuta, K., & Denly, M. (2021). External validity. Annual Review of Political Science, 24, 365–393.

*Flippin, M., Reisig, M. D., & Trinkner, R. (2019). The effect of procedural injustice during emergency 911 calls: A factorial vignette-based study. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 15(4), 651–660. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-019-09369-y

Gaines, B. J., Kuklinski, J. H., & Quirk, P. J. (2007). The logic of the survey experiment reexamined. Political Analysis, 15(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpl008

Gelman, A., & Carlin, J. (2014). Beyond power calculations: Assessing type S (sign) and type M (magnitude) errors. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9(6), 641–651. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614551642

Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D. J., & Yamamoto, T. (2014). Causal inference in conjoint analysis: Understanding multidimensional choices via stated preference experiments. Political Analysis, 22(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpt024

Hainmueller, J., Hangartner, D., & Yamamoto, T. (2015). Validating vignette and conjoint survey experiments against real-world behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(8), 2395–2400. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1416587112

Haller, M. B., Solhjell, R., Saarikkomäki, E., Kolind, T., Hunt, G., & Wästerfors, D. (2020). Minor harassments: Ethnic minority youth in the Nordic countries and their perceptions of the police. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 20(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895818800744

Hauser, D. J., Ellsworth, P. C., & Gonzalez, R. (2018). Are manipulation checks necessary? Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 998. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00998

*Hazen, K. P., & Brank, E. M. (2022). Do you hear what I hear?: A comparison of police officer and civilian fairness judgments through procedural justice. Psychology, Crime & Law, 28(2), 153–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2021.1900179

*Hazen, K. P. (2021). Procedural justice and identity: Comparing evaluations of police-civilian interactions. [Doctoral dissertation].

*Hellwege, J. M., Mrozla, T., & Knutelski, K. (2022). Gendered perceptions of procedural (in)justice in police encounters. Police Practice and Research, 23(2), 143–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2021.1924170

Hinds, L., & Murphy, K. (2007). Public satisfaction with police: Using procedural justice to improve police legitimacy. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 40(1), 27–42.

*Jeleniewski, S. A. (2014). Expanding legitimacy in the procedural justice model of legal socialization: Trust, obligation to obey and right to make rules [PhD Dissertation].

Johnson, D., Wilson, D. B., Maguire, E. R., & Lowrey-Kinberg, B. V. (2017). Race and perceptions of police: Experimental results on the impact of procedural (in)justice. Justice Quarterly, 34(7), 1184–1212. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2017.1343862

Jonathan-Zamir, T., & Weisburd, D. (2013). The effects of security threats on antecedents of police legitimacy: Findings from a quasi-experiment in Israel. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 50(1), 3–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427811418002

*Jones, A. M., Vaughan, A. D., Roche, S. P., & Hewitt, A. N. (2021). Policing persons in behavioral crises: An experimental test of bystander perceptions of procedural justice. Journal of Experimental Criminology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-021-09462-1

Kreps, S., & Roblin, S. (2019). Treatment format and external validity in international relations experiments. International Interactions, 45(3), 576–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629.2019.1569002

Lakens, D., & Caldwell, A. R. (2021). Simulation-based power analysis for factorial analysis of variance designs. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 4(1), 251524592095150. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245920951503

*Madon, N. S., Murphy, K., & Williamson, H. (2022). Justice is in the eye of the beholder: A vignette study linking procedural justice and stigma to Muslims’ trust in police. Journal of Experimental Criminology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-022-09510-4

Maguire, E. R., Lowrey, B. V., & Johnson, D. (2017). Evaluating the relative impact of positive and negative encounters with police: A randomized experiment. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 13(3), 367–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-016-9276-9

Mastrofski, S. D., Jonathan-Zamir, T., Moyal, S., & Willis, J. J. (2016). Predicting procedural justice in police–citizen encounters. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43(1), 119–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854815613540

Mazerolle, L., Bennett, S., Antrobus, E., & Eggins, E. (2012). Procedural justice, routine encounters and citizen perceptions of police: Main findings from the Queensland Community Engagement Trial (QCET). Journal of Experimental Criminology, 8(4), 343–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-012-9160-1

Mazerolle, L., Antrobus, E., Bennett, S., & Tyler, T. R. (2013a). Shaping citizen perceptions of police legitimacy: A randomized field trial of procedural justice: Shaping citizen perceptions of police. Criminology, 51(1), 33–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2012.00289.x

Mazerolle, L., Bennett, S., Davis, J., Sargeant, E., & Manning, M. (2013b). Procedural justice and police legitimacy: A systematic review of the research evidence. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 9(3), 245–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-013-9175-2

*McLean, K. (2020). Revisiting the role of distributive justice in Tyler’s legitimacy theory. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 16(2), 335–346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-019-09370-5

*McLean, K. (2021). Justice-restoring responses: A theoretical framework for understanding citizen complaints against the police. Policing and Society, 31(2), 209–228.https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2019.1704755

Metcalfe, C., & Pickett, J. T. (2021). Public fear of protesters and support for protest policing: An experimental test of two theoretical models. Criminology, 30. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12291

Montgomery, J. M., Nyhan, B., & Torres, M. (2018). How conditioning on posttreatment variables can ruin your experiment and what to do about it: Stop conditioning on posttreatment variables in experiments. American Journal of Political Science, 62(3), 760–775. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12357

Muralidharan, K., Romero, M., & Wüthrich, K. (2020). Factorial designs, model selection, and (incorrect) inference in randomized experiments. NBER Working Paper, No. 26562.

Murphy, K., Bradford, B., & Jackson, J. (2016). Motivating compliance behavior among offenders: Procedural justice or deterrence? Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43(1), 102–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854815611166

Murphy, K., Bradford, B., Sargeant, E., & Cherney, A. (2022). Building immigrants’ solidarity with police: Procedural justice, identity and immigrants’ willingness to cooperate with police. The British Journal of Criminology, 62(2), 299–319. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azab052

Nagin, D. S., & Telep, C. W. (2017). Procedural justice and legal compliance. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 5–28.