Abstract

Objectives

This study examines how stigma moderates the effect of procedurally just and unjust treatment on Muslims’ trust in police.

Methods

Survey participants were randomly assigned to receive one of two vignettes describing a traffic stop where officer treatment was manipulated (procedurally just/unjust). Muslims’ feelings of stigma were measured prior to the vignette, while trust was measured after the vignette.

Results

We found that the procedural justice vignette enhanced trust in police, and perceived stigma was associated with lower trust. For Muslims who felt highly stigmatized, however, experiencing police procedural justice had a weaker positive effect on trust when compared to those who felt low levels of stigmatization.

Conclusions

The results suggest that feelings of stigma can moderate how individuals view police-citizen interactions. Specifically, for those who observe or experience encounters with police believing that they or their cultural group are stigmatized, procedural justice will be less effective in promoting trust.

Similar content being viewed by others

In recent years, police services have increasingly emphasized the importance of fostering stronger police-community relations to build citizens’ trust in police. This prioritization of efforts is based on decades of research finding that when people view police as respectful, neutral, and fair, they are more likely to trust police, perceive police as legitimate, and indicate they will cooperate with police (see Donner et al., 2015 for review). As a result, procedural justice has been regarded as a proverbial “silver bullet” for improving police-citizen relations (Roché & Roux, 2017), particularly between police and ethnic and racial minority communities. While numerous studies have found that general perceptions of procedural justice are associated with more positive police-citizen relations, how pre-existing attitudes moderate the effect of procedural justice and injustice on minorities’ trust in police based on a specific encounter is less clear. Further, less is known about the extent to which police use of procedural justice is effective at promoting trust amongst those who may feel discriminated against.

Understanding how minority groups view and respond to police treatment is important. Existing research has found that ethnic and racial minorities tend to view police more negatively (e.g., Brown & Benedict, 2002; Kahn et al., 2017) and are significantly less likely to trust police than non-minorities (see Tyler, 2005; Tyler & Huo, 2002). However, while police agencies strive to implement procedurally just practices to foster minorities’ trust and confidence in police, this may not be sufficient to counter pre-existing negative perceptions. Some scholars have questioned whether procedural justice works equally for everyone, particularly for those who may feel that police hold preconceived biases about them personally or their ethnic or religious group more broadly (e.g., Madon & Murphy, 2021; Williamson et al., 2022). While several studies have found the effect of procedural justice on perceptions of police to be invariant across groups (e.g., Brown & Reisig, 2019; Wolfe et al., 2016), some scholars have questioned the universality of the positive procedural justice effect (Murphy, 2017; Tankebe, 2009).

Relatedly, how pre-existing attitudes can moderate the effect of procedural justice and injustice on minorities’ trust in police based on a specific encounter is not clear. Research outside of policing has found that demographic, personality, or attitudinal factors can moderate the effectiveness of procedural justice (Colquitt et al., 2006; Van den Bos et al., 2003). Stigma is one such attitudinal variable that has been found to moderate the procedural justice effect in policing. Drawing on survey data of Muslims residing in Australia, Murphy et al. (2020) found that the level of respondents’ stigmatization differentially influenced how they perceived procedural justice from police, with procedural justice being more effective for those who felt more stigmatized.

While we do not question the value of procedural justice in policing, Murphy et al.’s (2020) findings lead us to question whether procedural justice will always be equally received. We argue that the lens through which people view interactions with police is important to understand, particularly for those who feel they belong to a stigmatized group, and who likely anticipate routine bias from police. As one stigmatized minority group, Muslims have reported experiencing high levels of police discrimination and low levels of trust in police (Choudhury & Fenwick, 2011; Spalek, 2010). It is reasonable to assume that many Muslims likely anticipate that police will be procedurally unjust in encounters with them. Whether Muslims’ feelings of stigmatization may condition their experiences and perceptions of an encounter with police is the focus of the current study. We seek to better understand whether procedurally just treatment from police is readily received and how this in turn affects Muslims’ trust in police. To do this, we specifically examine how stigma moderates the relationship between procedurally just and unjust treatment on trust in police.

The importance of trust between Muslims and police

Trust in police is predicated on citizens’ subjective beliefs that police will behave in certain expected ways, including treating people respectfully, acting with integrity, and being effective. These expectations are derived from both personal and vicarious experiences with police (Jackson & Gau, 2016). Whether people confer trust on police is based on how they or people they know have been treated in the past (Hardin, 2002). As such, how people feel that police treat people like them is central to understanding whether trust is given. Trust in police is essential for both citizens and police. An absence of trust on the part of citizens can be detrimental to people’s willingness to voluntarily engage with police or to seek help from police (Murphy et al., 2014). For police, a distrusting public can translate to a lack of cooperation, making police work more difficult (Sunshine & Tyler, 2003).

Research suggests that many Muslims believe that police have come to see all Muslim people as “suspect” (Cherney & Murphy, 2016). Over the past 20 years, the rise of Islamophobia coupled with the increased police surveillance of Muslim people has led many Muslims to feel stereotyped and stigmatized (Blackwood et al., 2013; Pantazis & Pemberton, 2009; Spalek, 2010). This lack of trust is not viewed as one sided, however, with many Muslims perceiving police as equally distrusting of them. Within this context, it is not surprising that many Muslims report distrusting police (Cherney & Murphy, 2016; Madon & Murphy, 2021; Tyler et al., 2010). Procedural justice theory has been touted as one way to foster greater trust within such contexts.

Procedural justice and its connection to trust

According to procedural justice theory, when evaluating encounters with police, citizens value both fair process and fair treatment. To achieve this, citizens need to be given an opportunity to raise their concerns (voice), be treated in a fair and respectful way (respect), believe that an officer has made their decision based on the facts before them (neutrality), and trust police to act in their best interests (trustworthiness) (Tyler, 2006). Empirical research of both general populations as well as minority groups has found that when people perceive police as procedurally just, they are more likely to trust police (Donner et al., 2015; Maguire et al., 2017; Tyler, 2005). Even amongst groups who feel particularly stigmatized (e.g., Muslims), perceiving police as more procedurally just is correlated with higher levels of trust in police (Murphy et al., 2020). However, the strength of the procedural justice effect does appear to differ between stigmatized and unstigmatized individuals. In a study of Australian Muslims, Madon and Murphy (2021) found that procedural justice had a stronger effect on trust for those Muslims who perceived police as less biased toward their cultural group. For Muslims who perceived police as biased toward Muslims, procedural justice had a weaker association with trust in police. Such findings suggest that procedural justice effects may differ when accounting for individuals’ pre-existing beliefs and attitudes about police.

Studies have also found that Muslims who perceive police as procedurally unjust or biased toward Muslims are less likely to trust or voluntarily cooperate with police in the future (Cherney & Murphy, 2016; Madon & Murphy, 2021; Murphy et al., 2020). This is consistent with the broader literature showing perceptions of police bias or discrimination are associated with other minorities’ reduced trust in police (Van Craen & Skogan, 2015; see Kearns et al., 2020 for review).

A key limitation of the above-mentioned studies, however, is that they rely on cross-sectional survey data to draw conclusions about the relationship between procedural justice and trust in police. While these studies have made important contributions to the knowledge base, this methodology naturally limits the causal inferences that can be made about the effects of police treatment on citizens’ perceptions of police (Johnson et al., 2017). Further, much of the existing literature study global perceptions about whether police are generally procedurally just. Very few studies examine the consequences of procedural justice or injustice on trust during a specific police-citizen interaction. As such, the extent to which procedurally just or unjust treatment has a causal effect on minorities’ trust in police is less clear. Finally, whether pre-existing feelings of stigmatization moderate the causal effect of procedural justice on citizens’ trust in police also remains underexplored. To overcome the limitations of existing research, experimental methodology is required to better understand how these different variables are causally related to each other in police-citizen encounters.

Procedural justice during police-citizen encounters: emerging experimental evidence

Recent scholarship has employed experimental approaches to test procedural justice effects on key outcomes such as cooperation and obligation to obey the law (e.g., Maguire et al., 2017), police legitimacy (e.g., Brown & Reisig, 2019), and trust in police (MacQueen & Bradford, 2015; Maguire et al., 2017; Sahin, 2014). Early studies employed randomized controlled field trials to examine the effect of changing a police procedure on citizens’ perceptions of police (MacQueen & Bradford, 2015; Mazerolle et al., 2013; Sahin, 2014). While these trials have several methodological advantages, they cannot manipulate police treatment to include a negative or procedurally unjust treatment condition (Maguire et al., 2017). After all, it would be unethical for police agencies to instruct their officers to speak rudely to members of the public to examine the consequences of experiencing poor police treatment.

Experimental vignette designs that manipulate various hypothetical police-citizen interactions, in contrast, have been used to test a broader range of police-citizen interactions and their consequences by manipulating both fair and unfair police treatment of citizens (Brown & Reisig, 2019; Nivette & Akoensi, 2017; Reisig et al., 2018; Solomon, 2019; Tankebe, 2021; Trinkner et al., 2019). However, while the use of experimental methods to test both procedurally just and unjust treatment is growing, few studies have examined the effect of procedural justice, and lack thereof, on trust in police. Drawing on a randomized video vignette design with college students in the USA, Maguire et al. (2017) tested the effects of students observing positive, negative, and neutral police treatment of citizens during traffic stops on participants’ obligation to obey police directives, willingness to cooperate with police, and trust in police. The authors found that viewing a video of police acting in a procedurally just manner positively shaped all three outcome variables. Police acting in a procedurally unjust way, in contrast, negatively affected participants’ perceptions of all three outcome variables.

Limited experimental research has tested the effect of procedural justice and injustice on key outcomes for ethnic and racial minority groups. Consequently, less is known about how minority group members interpret police use of procedural justice or injustice during a specific encounter with a citizen and how this affects their trust in police. As Johnson et al. (2017) assert, it is important to consider minorities’ responses to different types of police-citizen encounters due to the over-policing that minorities tend to experience. Again, drawing on a sample of college students, Johnson et al. (2017) employed a randomized video vignette of a traffic stop that manipulated how police treated the driver (positive, negative, or neutral) and the driver’s race (Black or White). Johnson et al. (2017) found that viewing a video where the police officer treated the driver in a procedurally just way strongly and positively shaped participants’ trust and confidence in police. The authors, however, found an asymmetrical effect of viewing police injustice on perceptions of police, with procedurally unjust treatment having a larger effect than procedurally just treatment. While the race of the driver in the vignette had no effect, Black respondents viewed the police more negatively across all three police treatment conditions.

In sum, a growing body of experimental research on procedural justice has attempted to elucidate the causal relationships between police treatment and citizens’ perceptions of police. However, few studies have tested the effects of both fair and unfair police treatment on citizens’ trust in police, with only one examining the effect of police treatment with racial minorities (see Johnson et al., 2017). The current study thus begins to address these gaps while also exploring the moderating effect of minority members’ perceived stigma on trust.

The role of stigma in interpreting police treatment

Feelings of stigma can arise when individuals perceive that their group, cultural membership, or physical appearance is associated with a negatively viewed identity (Major & O’Brien, 2005). Muslims who believe that society and police conflate Islam with terrorism may perceive such stigma. Scholars assert that people who perceive a greater level of stigmatization are more sensitive to perceived disrespect or unfair treatment (Major & O’Brien, 2005). For instance, if people enter encounters with police believing that they belong to a stigmatized group, they may be more likely to perceive police treatment through a negative lens. Expectancy theory further posits that people who anticipate a negative outcome are more likely to see negativity in that encounter (Shapiro & Kirkman, 2002). Taken together, this suggests that people do not view interactions as “blank slates,” but rather with different understandings of how they will be treated (Major & O’Brien, 2005). Further, whether police act in a procedurally just manner or not, this negative lens may cloud how citizens interpret police behavior.

Understanding why stigma may condition the effect of procedurally just treatment on Muslims’ trust in police can be linked to how people who feel stigmatized respond to those who are perceived to have negatively labeled them. Hardin (2004) suggests that distrust can be a coping mechanism that protects individuals from perceived harm. As the source of some of their stigma, Muslims may choose to distrust police because it enables Muslims to protect themselves from future harmful situations that might involve police. In a similar vein, Zhang et al., (2020: 308) suggest that “people might mistrust those who are prejudiced against them.” Applying this to the policing of Muslim people, it is certainly possible that Muslims who feel highly stigmatized will interpret a procedurally just policing encounter as unjust, which will have a corresponding negative influence on their trust in police. As such, it is important to understand whether such attitudes can impact the effectiveness of procedural justice on citizens’ trust in police.

Current study

The present study explores how stigma moderates the relationship between police procedural justice/injustice on Muslims’ trust in police. To do this, we utilize a between-groups vignette experiment describing a hypothetical police-citizen interaction with a Muslim citizen. In one scenario, the police officer is depicted as behaving in a procedurally just way; in the other, the officer is portrayed as behaving in a procedurally unjust way. We examine how this manipulation causally affects Muslims’ trust in the officer depicted in the scenario. Importantly, we also test how pre-existing feelings of stigmatization moderate the effectiveness of observing procedural justice on Muslims’ trust in police.

Our study extends prior research and makes two important contributions to procedural justice scholarship. This study is the first to utilize a vignette experiment to test the causal effect of police use of procedural justice and injustice on Muslims’ trust in police. While there has been a recent uptick in experimental research in criminology, only two prior studies have looked at the effect of both procedurally just and unjust treatment on trust in police (Johnson et al., 2017; Maguire et al., 2017). However, both studies only tested the direct effect of procedural justice/injustice on trust. How procedural justice is moderated by other attitudinal factors has not been tested with respect to citizen trust in police. Additionally, while previous research has demonstrated that minority group members often hold more negative views of police, limited research has examined the causal effect of police treatment in encounters with minority group members (Solomon, 2019). To date, only one experimental vignette study has specifically tested the effect of procedural justice and injustice on minority group members’ perceptions of trust in police (Johnson et al., 2017). Informed by the research synthesized above, we test the following hypotheses:

-

H1: Muslim participants who receive a vignette where the officer behaves in a procedurally just manner will have higher trust in the police officer than those who receive a vignette where the officer is procedurally unjust;

-

H2: Muslim participants with stronger feelings of stigma will be less trusting of the police officer after reading the vicarious vignette encounter;

-

H3: Levels of stigma will moderate Muslim participants’ perceptions of the police officer’s treatment in the vignette; specifically, when the officer’s treatment is described as procedurally just, Muslims who feel less stigmatized by police prior to reading the vignette will be more trusting of police.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The current study draws on survey data collected in July 2020 from a sample of 504 Arab-Muslim participants residing in Sydney, Australia. Sydney was the chosen site to conduct this study for two reasons: (1) the majority of Muslims in Australia live in Sydney (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2016); and (2) previous research has found that police-Muslim relations are more strained in Sydney when compared to other major Australian cities, with Muslims from Arab-league nations having the most strained relations (Murphy et al., 2015; Murphy, in press).

Australian Muslims comprise only 2.6% of Australia’s population and approximately 5% of Sydney’s population (ABS, 2016). Thus, non-probability sampling techniques are necessary to effectively recruit people from such a small population. An ethnic naming system was adopted, whereby a list of 525 common Muslim surnames was created. From here, the electronic telephone directory in Sydney was used to generate a random sampling frame of 8,699 potential participants with these surnames (see Murphy & Williamson, 2021 for a full list of surnames used). The survey was administered by a Sydney-based research company who specializes in the recruitment of culturally and linguistically diverse samples. Muslim interviewers fluent in Arabic and English were retained to field the survey.

Potential participants were contacted randomly from the sample lists and invited to participate in a survey. To ensure the random selection of the participant in each household, interviewers asked to speak to a person aged 18 + whose birthday was most imminent. From here, interviewers ascertained eligibility to participate in the study by asking if the participant was Muslim and had originated from one of 22 Arab-league nations. Quotas were applied for country of birth (50% Australia; 50% overseas), gender (50% female; 50% male), and age (50% < 30 years of age; 50% > 30 years of age) to ensure the final sample closely represented population demographics of Arab Muslims living in Sydney. Face-to-face interviews were conducted in participant’s preferred language (i.e., Arabic or English).

Of the 8,699 sample records, 5,563 call attempts were made, whereby only 1,613 individuals met all eligibility requirements for the study. Of the 1,613 eligible individuals, 504 people agreed to participate in the research (response rate of 31.25%). Surveys took approximately 50 min to complete, and participants were given a $40 honorarium for their time. During data screening, two participants were removed from the sample, resulting in a final usable sample of 502.Footnote 1 The average age of participants was 33.9 years old; 50.2% were male and just over half were married or in a de-facto relationship (50.8%). Additionally, half of the sample reported being born overseas (50.2%), almost one-third worked full-time (33.1%), and 35.5% held a tertiary qualification. When compared to Australian census data, the survey sample was reflective of Sydney’s Muslim population when considering gender, age, marital status, and country of birth (see Table 1).

Measures

In addition to the vignette manipulation variable, three multi-item scales were constructed for stigma, trust in the police officer, and Muslim identification with their faith. All scale items were measured on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Table 2 outlines the items used to construct these scales.

Key independent variables

Vignette manipulation (police officer treatment)

Embedded in the final section of the survey was a between-groups vignette experiment. Participants were presented with one of two vignette scenarios depicting a vicarious police encounter (see Appendix for vignettes). Each scenario portrayed an interaction between a male Muslim citizen and a police officer whereby the police officer randomly pulled over the male driver following reports of a fictional terrorist attack in the area. In the scenario, the male’s car was said to fit the description of a car seen fleeing the scene of the attack. The police officer’s treatment of the citizen was manipulated in the vignette (0 = procedurally unjust (n = 252) vs. 1 = procedurally just (n = 250)). The vignettes included key elements of procedural justice, including voice, respect, neutrality, and trustworthiness. Randomization checks revealed no significant differences amongst participants across the two vignette conditions when disaggregated by gender, marital status, or educational attainment, although older participants were more likely to be allocated to the procedural injustice condition (M = 35.36 years) compared to the procedural justice condition (M = 32.50 years; t(500) = 2.43, p < 0.02). Further, an additional test was conducted to ensure that participants correctly identified the police officer treatment of the citizen as procedurally just or unjust based on their random assignment. This indicated that those assigned to the procedurally just condition were significantly more likely to view the police officer’s treatment of the citizen as procedurally just (M = 3.99, SD = 0.95, n = 250) than those in the procedurally unjust condition (M = 2.18, SD = 1.02, n = 252; t(500) = 3.30, p < 0.001) indicating that participants were able to correctly identify the quality of the treatment the citizen received.

Stigma

Four items were used to measure stigma and preceded the presentation of the vignettes. Participants were asked the extent to which they felt under scrutiny or viewed as a potential terrorist because of their religion (e.g., “I feel at risk of being accused of terrorist activities because of my faith”). Items were adapted from the work of Murphy et al. (2020), with a higher score on this scale reflecting stronger feelings of stigma (mean = 2.75; SD = 1.21; α = 0.94).

Dependent variable

Trust in the police officer

Four items were used to create the trust in the police officer scale. After reading their respective vignette, participants were asked the extent to which they trusted the police officer depicted in the scenario (e.g., “The police officer acted in a trustworthy manner”). The items were adapted from Gau’s (2014) work. A higher score on this scale indicates greater trust in the police officer portrayed in the vignette (mean = 3.23; SD = 1.26; α = 0.91).

Demographic and control variables

Demographic and control variables were also included based on prior research which has found these factors to be associated with trust in police (see e.g., Tyler & Huo, 2002; Pass et al., 2020). Demographic variables included age, gender (0 = male; 1 = female), country of birth (0 = Australian born; 1 = overseas born), marital status (0 = married; 1 = not married), employment status (0 = employed; 1 = unemployed), and educational attainment (1 = no/limited formal schooling to 10 = postgraduate degree). Control variables were included to measure the frequency that participants attended mosque (1 = never to 7 = daily; M = 3.26; SD = 1.65) and the frequency of police contact in the previous 2 years (mean = 1.13, SD = 2.63). Finally, Muslims’ identity with their faith was operationalized using three items. These items also preceded the vignette and asked participants the extent to which they identified with their faith (e.g., “I am proud to be Muslim”). Items were adapted from the work of Murphy et al. (2010). A higher score on this scale indicates a stronger identification with the Muslim faith (mean = 4.71; SD = 0.63; α = 0.87).

Factor analysis

All multi-item scales were subjected to an exploratory factor analysis to test the convergence and discriminant validity of the items (see Table 2). Three distinct factors were identified with Eigenvalues > 1. All stigma, Muslim identity, and trust in the police officer items loaded as expected, with no cross-loadings between factors. Scales were subsequently created by computing a mean score scale.

Results

Bivariate correlations

The correlation matrix presented in Table 3 reveals that the police officer treatment variable was positively correlated with trust, such that trust in the officer was higher amongst participants who received the procedurally just vignette condition when compared to those who received the procedurally unjust vignette condition. In addition, stigma was negatively correlated with age, education, and trust in police. This suggests that older participants, more educated participants, and those who trusted the police officer in the vignette more also felt less stigmatized. However, stigma was positively correlated with contact with police, which suggests that those Muslims who had more frequent contact with police were more likely to feel stigmatized.

t-Test

A t-test was conducted to test H1 and H2 by looking at differences between the procedural justice and injustice conditions on Muslims’ trust in police. We found that participants who received the vignette describing the police officer’s behavior as procedurally just (M = 4.00, SD = 0.99, n = 250) were significantly more likely to trust police when compared to those who received the vignette describing the police officer’s behavior as procedurally unjust (M = 2.46, SD = 0.99, n = 252; t(500) = 0.375, p < 0.001).

Regression analysis

Building on this, an ordinary least squares regression analysis was conducted to test the causal effect of police treatment (the vignette manipulation) on trust in police (H1) (Table 4). Variables were entered into the regression in blocks. In block 1, the vignette manipulation variable of police treatment, the stigma scale, the Muslim identity scale, and the key demographic variables were entered into the model. In block 2, a 2-way interaction term (police treatment × stigma) was mean centered prior to being entered in the model. A test of multi-collinearity was conducted but not detected.

Block 1 accounted for 45.8% of the variance in trust in the police officer. Importantly, the vignette manipulation (i.e., police officer treatment) had a positive causal effect on trust (β = 0.635; p < 0.001), where participants trusted the officer in the procedural justice condition more than the officer in the procedurally unjust condition (H1 supported). Second, stigma was negatively associated with trust (β = − 0.251; p < 0.001). More stigmatized participants reported feeling less trusting of the officer in the vignette (H2 supported). Finally, Muslim identification was positively associated with trust (β = 0.102; p < 0.01); that is, the more participants identified with their Muslim faith, the more they trusted the officer. None of the demographic variables was significantly associated with trust.

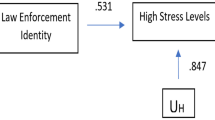

In block 2, (R2 change = 0.007), the 2-way interaction term between stigma and officer treatment was entered and was significant and negative (β = − 0.121, p < 0.05). Figure 1 presents the interaction effect graphically. Simple effects tests were conducted at − 1 (low) and + 1 (high) standard deviations of the stigma variable and reveal that the positive effect of procedural justice on trust was weaker when the participant reported feeling more stigmatized (β = 0.548, p < 0.001) compared to when the participant reported feeling less stigmatized (β = 0.720, p < 0.001). These findings suggest that pre-existing feelings of stigma do indeed moderate how Muslims perceive police treatment during a police-citizen interaction (H3 supported).

Discussion

This study aimed to better understand how procedural justice causally affects Muslims’ trust in police and whether pre-existing feelings of stigma moderate this relationship. We predicted that Muslims exposed to a vicarious procedurally just police encounter would have greater trust in police, while those exposed to a procedurally unjust encounter would have lower trust in police (H1). We also predicted that those who felt more highly stigmatized prior to the vicarious police-citizen encounter would be less trusting of the police officer in the vignette (H2). Finally, we hypothesized that greater feelings of stigma would moderate the causal effect of procedural justice/injustice on trust by negatively affecting how participants perceived the police treatment of the Muslim citizen (H3).

Overall, we found support for these three hypotheses. Not surprisingly, we found that police use of procedural justice in the vicarious encounter had a positive causal effect on Muslims’ trust in the officer depicted in the scenario. This supports findings in prior correlational studies which show that general perceptions of procedural justice are associated with enhanced public trust in police (e.g., Murphy et al., 2014; Tyler & Huo, 2002). In addition, our findings provide support for a causal relationship between procedural justice and trust and do so using a minority group sample (i.e., Muslims). Limited research to date has tested the causal effects of procedurally just and unjust treatment on minority groups members’ views of police. Our results thus fill an important evidence gap.

We also found that Muslims who felt more stigmatized were less trusting of the police officer in the vignette. Given the extent to which Muslims in western democratic countries have been subjected to suspicion and surveillance by police over the last two decades (Pantazis & Pemberton, 2009), this finding is not surprising. This finding also confirms prior cross-sectional studies which have found that greater feelings of stigma are associated with lower levels of trust in police (e.g., Murphy et al., 2020; Watson & Angell, 2013). We return to this finding below, offering reasons why stigma affects trust in this way.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, we found evidence that stigma does indeed moderate the effect of procedural justice on trust in police. For those who felt more stigmatized, viewing a police officer in the vignette act in a procedurally just manner was substantially less effective in promoting trust when compared to those who felt less stigmatized. This suggests that stigma appears to serve as a lens through which police-citizen encounters are perceived. Specifically, stigma seems to predispose individuals to perceive events in a more negative light, regardless of the objective reality of the event, and in turn, weakens the effect of fair treatment. This finding builds on the limited experimental research conducted to date on the effect of both procedurally just and unjust treatment by demonstrating one way in which the procedural justice effect on minority group members’ trust in police can be conditioned. The moderating role of stigma found in our study further highlights why procedural justice may be less effective when applied to some citizens. Our findings thus challenge the invariance thesis when it comes to minority group members experiences with procedural justice.

Implications

Based on our findings, there are various reasons why stigma might affect trust in this way. The first relates to how stigma may impact people’s expectations of police treatment. Scholars suggest that the extent to which people feel they or their group are unfairly labeled does not merely result in feeling unjustly stereotyped. Rather, it can also have negative flow-on effects for how people interpret their treatment and expect to be treated in the future. Further, as Major and O’Brien (2005: 40) assert, “non-stigmatized and stigmatized groups in particular react very differently to the same local situation, in part because they differ in the collective representations they bring to the situation.” This contextual difference may help explain differing responses to procedural justice found in our study.

Related to this latter point, psychological research suggests that pre-existing contextual knowledge can affect an individual’s processing of ambiguous information (Fiske & Taylor, 1991). This is known as “priming,” which occurs when exposure to an earlier stimulus influences how one reacts to a similar and subsequent stimuli in the future (Erdley & D’Agostino, 1988). According to research on the effects of priming, how individuals interpret information depends on the knowledge structures (i.e., schemas) that become active when exposed to a subsequent event or stimulus. People can thus react differently to an identical stimulus based on which schemas become activated. Braga et al. (2014) noted that this can have consequences for police departments. Prior contextual factors (e.g., repeated experiences of police bias in the past and feeling stigmatized) might activate a negative schema about police and will prime those citizens’ subsequent evaluations of police behavior accordingly. When viewing the same event, however, another person whose activated schema about police is positive will likely perceive the event very differently. As such, citizens’ assessments of police officer fairness or unfairness can be “powerfully dependent on pre-existing knowledge structures that are positive or negative towards the police” (Braga et al., 2014: 600). Hence, the greater propensity for distrust amongst stigmatized individuals may help to explain why procedural justice had a weaker positive effect on trust amongst those Muslims who felt more stigmatized. It is possible that those who believe that police hold negative views of Muslim people may be primed to bring a different viewpoint or negative schema to police-citizen interactions.

Having said this, despite highly stigmatized people being less trusting of police and while stigma appears to moderate the effectiveness of procedural justice, it is important to highlight that procedural justice was also positively associated with greater trust in police for both unstigmatized and highly stigmatized Muslims, even if the strength of the effect differed. This is in line with prior correlational studies which have found this weaker but positive effect of procedural justice on trust (Murphy & McPherson, 2022). This suggests that procedural justice policing can be beneficial if the aim is to build trust in minority communities. By adhering and committing to procedural justice in their interactions with marginalized and stigmatized minority groups, over time, police may be able to gain some ground in promoting better relationships.

Our findings also have important implications for police services working with diverse groups who may feel similarly stigmatized in society. While police cannot eradicate Islamophobia and other stigma that overshadows some communities they serve, having a better understanding of why people may not respond immediately to fair and respectful treatment is important. Police officers who employ procedurally just practices in their dealings with citizens should not take this as a signal of failure. Rather, for some, procedural justice may only be received following repeated fair and respectful interactions that serve to break down pre-existing beliefs and attitudes about how police view and treat people from their group. This is important for police to be aware of because theories on stigma suggest that if authorities in turn respond negatively to such citizens, this can serve to re-affirm negative expectations and continue to perpetuate this lack of trust between the two parties (Major & O’Brien, 2005).

Coupled with this strategy, police agencies may also consider using the media to highlight positive news stories. The public routinely hear stories of how police mistreat minorities. The same cannot be said for stories relaying positive encounters (Renauer & Covelli, 2010). Police should therefore work actively to counter this negative commentary by ensuring that good news stories about police-minority relations are disseminated. As Renuaer and Covelli (2010: 508) highlight, this “is not meant to diminish real injustices and abuse of power, but to recognize that the ‘playing field’ for public opinion appears imbalanced.” Such an approach could be used to promote some of the positive initiatives police services have made in partnering with minority communities. This is particularly important given the strong influence that vicarious experiences have on individuals’ views of police (Fagan & Tyler, 2005). Providing people with a counter narrative to the “tough on terror” discourse that politicians have heralded since 9/11 may help to reduce feelings of stigma and foster greater trust in police.

Limitations and future directions

While our study has several strengths, particularly surrounding the experimental nature of the study, there are some noteworthy limitations. First, the use of the telephone directory—even one that contains mobile phone numbers—has the potential to exclude people who have unlisted landlines or mobile phone numbers. Second, this study is based on an artificial interaction between police and a Muslim citizen which was read by participants. It was not a real encounter depicting a police-citizen interaction. The vicarious nature of the vignette means that participants are observing police treatment of someone else, not themselves. It is possible that participants may have responded differently had they personally experienced a real positive or negative encounter. Finally, while the sample used closely resembles the broader Muslim population in Australia, the results are not generalizable to all Muslims in Australia nor elsewhere. These limitations could affect the external validity of the findings. Attempts to replicate the results in different countries or using different minority groups with video vignettes of real police-citizen interactions will elucidate whether this pattern of findings found here is robust and generalizable.

Conclusion

This study examined the effect of both procedurally just and unjust treatment on Muslims’ trust in police and whether pre-existing feelings of stigma cloud how individuals view police-citizen interactions. Our findings suggest that feelings of stigma can negatively shape how individuals perceive and evaluate citizen interactions with police. More specifically, even when officers act in fair and respectful ways, feeling stigmatized can dampen the positive effect of procedural justice on trust in police. As such, even when procedural justice is given, it may not be fully received. While police agencies are increasingly encouraged to employ procedural justice practices in their dealings with minority communities, it is important for them to be aware that when they do not immediately see the fruits of their (procedurally just) labor, their efforts are not in vain. Rather, citizens may require greater time and additional trust-building strategies before the full effects of procedural justice can be seen and received.

Notes

For one participant, the number of police contacts recorded was implausible as it far exceeded the number of days in a year. This was assumed to be a data entry error and therefore the case was removed. An additional participant was removed as they had noted “other” for their gender.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2016). 2016 census. Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Blackwood, L., Hopkins, N., & Reicher, S. (2013). I know who I am, but who do they think I am? Muslim perspectives on encounters with airport authorities. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 36(6), 1090–1108.

Braga, A. A., Winship, C., Tyler, T. R., Fagan, J., & Mears, T. L. (2014). The salience of social contextual factors in appraisals of police interactions with citizens: A randomized factorial experiment. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 30(4), 599–627.

Brown, B., & Benedict, W. R. (2002). Perceptions of the police: Past findings, methodological issues, conceptual issues and policy implications. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 25(3), 543–580.

Brown, K. L., & Reisig, M. D. (2019). Procedural injustice, police legitimacy, and officer gender: A vignette-based test of the invariance thesis. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 37(6), 696–710.

Cherney, A., & Murphy, K. (2016). Being a ‘suspect community’ in a post 9/11 world – The impact of the war on terror on Muslim communities in Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 49(4), 480–496.

Choudhury, T., & Fenwick, H. (2011). The impact of counter-terrorism measures on Muslim communities. International Review of Law, Computers & Technology, 25(3), 151–181.

Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., Judge, T. A., & Shaw, J. C. (2006). Justice and personality: Using integrative theories to derive moderators of justice effects. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Process, 100(1), 110–127.

Donner, C., Maskaly, J., Fridell, L., & Jennings, W. G. (2015). Policing and procedural justice: A state of the art review. Policing: An International Journal, 38(1), 153–172.

Erdley, C. A., & D’Agostino, P. R. (1988). Cognitive and affective components of automatic priming effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(5), 741–747.

Fagan, J., & Tyler, T. R. (2005). Legal socialization of children and adolescents. Social Justice Resarch, 18(3), 217–241.

Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (1991). Social cognition (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Gau, J. M. (2014). Procedural justice and police legitimacy: A test of measurement and structure. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 39(2), 187–205.

Hardin, R. (2002). Trust and trustworthiness. Russell Sage Foundation.

Hardin, R. (2004). Distrust: Manifestations and management. In R. Hardin (Ed.), Distrust (pp. 3–33). Russell Sage.

Jackson, J., & Gau, J. M. (2016). Carving up concepts? Differentiating between trust and legitimacy in public attitudes towards legal authority. In T. Neal, E. Shockley, L. PytlikZillig, & B. Bornstein (Eds.), Interdisciplinary perspectives on trust: Towards theoretical and methodological integration (pp. 49–70). Springer.

Johnson, D., Wilson, D. B., Maguire, E. R., & Lowrey-Kinberg, B. V. (2017). Race and perceptions of police: Experimental results on the impact of procedural (in)justice. Justice Quarterly, 34(7), 1184–1212.

Kahn, K. B., Lee, J. K., Renauer, B., Henning, K. R., & Stewart, G. (2017). The effects of perceived phenotypic racial stereotypicality and social identity threat on racial minorities’ attitudes about police. The Journal of Social Psychology, 157(4), 416–428.

Kearns, E. M., Ashooh, E., & Lowrey-Kinberg, B. (2020). Racial differences in conceptualizing legitimacy and trust in police. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45, 190–214.

MacQueen, S., & Bradford, B. (2015). Enhancing public trust and police legitimacy during road traffic encounters: Results from a randomised controlled trial in Scotland. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 11(3), 419–444.

Madon, N. S., & Murphy, K. (2021). Police bias and diminished trust in police: A role for procedural justice? Policing: An International Journal, 44(6), 1031–1045.

Maguire, E. R., Lowrey, B. V., & Johnson, D. (2017). Evaluating the relative impact of positive and negative encounters with police: A randomized experiment. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 13(3), 367–391.

Major, B., & O’Brien, L. T. (2005). The social psychology of stigma. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 393–421.

Mazerolle, L., Antrobus, E., Bennett, S., & Tyler, T. R. (2013). Shaping citizen perceptions of police legitimacy: A randomized field trial of procedural justice. Criminology, 51(1), 33–63.

Murphy, K. (2017). Challenging the ‘invariance’ thesis: Procedural justice policing and the moderating influence of trust on citizens’ obligation to obey police. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 13, 429–437.

Murphy, K. (in press). Scrutiny, legal socialization and defiance: Understanding how procedural justice and bounded-authority concerns shape Muslims’ defiance toward police. Journal of Social Issues.

Murphy, K., Cherney, A., & Barkworth, J. (2015). Avoiding community backlash in the fight against terrorism: Research report. Griffith University.

Murphy, K., & Williamson, H. (2021). Police-Muslim relations survey: Technical report. Engaging Muslims in the fight against terrorism project. Griffith Criminology Institute.

Murphy, K., Murphy, B., & Mearns, M. (2010). The 2007 public safety and security in Australia survey: Survey methodology and preliminary findings. Alfred Deakin Research Institute.

Murphy, K., Mazerolle, L., & Bennett, S. (2014). Promoting trust in police: Findings from a randomised experimental field trial of procedural justice policing. Policing and Society, 24(4), 405–424.

Murphy, K., Madon, N. S., & Cherney, A. (2020). Reporting threats of terrorism: Stigmatisation, procedural justice and policing Muslims in Australia. Policing and Society, 30(4), 361–377.

Murphy, K. & McPherson, B. (2022). Fostering trust in police in a stigmatized community: When does procedural justice and police effectiveness matter most to Muslim citizens? International Criminology, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43576-021-00040-z

Nivette, A. E., & Akoensi, T. D. (2017). Determinants of satisfaction with police in a developing country: A randomised vignette study. Policing & Society, 29(4), 471–487.

Pantazis, C., & Pemberton, S. (2009). From the ‘old’ to the ‘new’ suspect community: Examining the impacts of recent UK counter-terrorist legislation. The British Journal of Criminology, 49(5), 646–666.

Pass, M. D., Madon, N. S., Murphy, K., & Sargeant, E. (2020). To trust or distrust?: Unpacking ethnic minority immigrants’ trust in police. The British Journal of Criminology, 60(5), 1320–1341.

Reisig, M. D., Mays, R. D., & Telep, C. W. (2018). The effects of procedural injustice during police-citizen encounters: A factorial vignette study. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 14, 49–58.

Renauer, B. C., & Covelli, E. (2010). Examining the relationship between police experiences and perceptions of police bias. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 34(3), 497–514.

Roché, S., & Roux, G. (2017). The “silver bullet” to good policing: A mirage. Policing: An International Journal, 40(3), 514–528.

Sahin, N. M. (2014). Legitimacy, procedural justice and police-citizen encounters [Doctoral dissertation]. Rutgers Graduate School Newark.

Shapiro, D. L., & Kirkman, B. L. (2002). Anticipatory injustice: The consequences of expecting injustice in the workplace. In J. Greenburg & R. Corpanzano (Eds.), Advances in organizational justice. Stanford University Press.

Solomon, S. J. (2019). How do the components of procedural justice and driver race influence encounter-specific perceptions of police legitimacy during traffic stops? Criminal Justice and Behavior, 46(8), 1200–1216.

Spalek, B. (2010). Community policing, trust, and Muslim communities in relation to ‘new terrorism.’ Politics & Policy, 38(4), 789–815.

Sunshine, J., & Tyler, T. R. (2003). The role of procedural justice and legitimacy in shaping public support for policing. Law & Society Review, 37(3), 513–548.

Tankebe, J. (2009). Public cooperation with the police in Ghana: Does procedural fairness matter? Criminology, 47(4), 1265–1293.

Tankebe, J., et al. (2021). Moral contexts of procedural (in)justice effect on public cooperation with police: A vignette experimental study. In Kutnjak Ivkovic (Ed.), Exploring contemporary police challenges. Routledge.

Trinkner, R., Mays, R. D., Cohn, E. S., Van Gundy, K. T., & Rebellon, C. J. (2019). Turning the corner on procedural justice theory: Exploring reverse causality with an experimental vignette in a longitudinal survey. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 15(4), 661–671.

Tyler, T. R. (2005). Policing in black and white: Ethnic group differences in trust and confidence in the police. Police Quarterly, 8(3), 322–342.

Tyler, T. R. (2006). Why people obey the law. Princeton University Press.

Tyler, T. R., & Huo, Y. J. (2002). Trust in the law: Encouraging public cooperation with the police and courts. Russell Sage Foundation.

Tyler, T., Schulhofer, S., & Huq, A. (2010). Legitimacy and deterrence effect in counterterrorism policing: A study of Muslim American. Law & Society Review, 44(2), 365–402.

Van Craen, M., & Skogan, W. (2015). Differences and similarities in the explanation of ethnic minority groups’ trust in the police. European Journal of Criminology, 12(3), 300–323.

Van den Bos, K., Maas, M., Waldring, I. E., & Semin, G. R. (2003). Toward understanding the psychology of reactions to perceived fairness: The role of affect intensity. Social Justice Research, 16(2), 151–168.

Watson, A. C., & Angell, B. (2013). The role of stigma and uncertainty in moderating the effect of procedural justice on cooperation and resistance in police encounters with person with mental illnesses. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 19(1), 30–39.

Williamson, H., Murphy, K.& Madon, N.S. (2022). The negative implications of relative deprivation: An experimental of vicarious police contact and Muslims’ perceptions of police bias. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, online first. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2022.2058472

Wolfe, S. E., Nix, J., Kaminski, R., & Rojek, J. (2016). Is the effect of procedural justice on police legitimacy invariant? Testing the generality of procedural justice and competing antecedents of legitimacy. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 32(2), 253–282.

Zhang, M., Barreto, M., & Doyle, D. (2020). Stigma-based rejection experiences affect trust in others. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(3), 308–316.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This work was supported by the Australian Research Council Future Fellowship Scheme under Grant No: FT180100139.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Vignette A—procedural justice

A young Muslim man is driving home after attending Friday prayers when he is pulled over by a police patrol car. As he waits in his car at the side of the road, a police officer approaches the driver’s side of the car with his hand on his gun. The police officer says: “Step out of the car and keep your hands visible.” Once the young man is out of the car, the police officer states “I will be undertaking a search of both you and your car.”

The Muslim man is then asked to explain where he has come from and the police officer listens patiently. The police officer then explains “I have just received reports of a man attempting to stab members of the public and your car fits the description of a car seen fleeing the scene. I am responding to a suspected terrorism incident.”

The police officer explains that it is his duty to ensure the public remains safe. The police officer pats the young man down and begins his search of the car. The police officer finds nothing to suggest the man was involved in any terrorism incident. The officer then politely asks the young man for his contact details, provides his own badge number to the young man, invites the man to ask any questions before leaving, and apologizes for causing the man any inconvenience. The officer thanks the man and says he is free to go. The police officer returns to his patrol car and drives away.

Vignette B—procedural injustice

A young Muslim man is driving home after attending Friday prayers when he is pulled over by a police patrol car. As he waits in his car at the side of the road, a police officer approaches the driver’s side of the car with his hand on his gun. The police officer forcefully says: “Step out of the car and keep your hands visible.” Once the young man is out of the car the police officer states “I will be undertaking a search of both you and your car.”

The police officer then raises his voice at the young man and demands to know where the man has come from. When the young man tries to explain where he has been, the officer cuts him off mid-sentence. The police officer states “I have received reports of a man attempting to stab members of the public and your car fits the description of a car seen fleeing the scene. I am responding to a suspected terrorism incident.” “Are you the terrorist?”.

The police officer then roughly pats the young man down and begins his search of the car. The police officer finds nothing to suggest the man was involved in any terrorism incident. The officer then makes a condescending comment about the man’s appearance and takes down the young man’s contact details. The police officer tells the man he has wasted his time but tells him he is free to go. The police officer returns to his patrol car and drives away.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visithttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Madon, N., Murphy, K. & Williamson, H. Justice is in the eye of the beholder: a vignette study linking procedural justice and stigma to Muslims’ trust in police. J Exp Criminol 19, 761–783 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-022-09510-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-022-09510-4