Abstract

Objectives

This study examines US popular support for mechanisms that provide early release and “second chances” for individuals serving long-term prison sentences.

Methods

An experiment using a national sample of US adults (N=836).

Results

Data showed moderate, consistent levels of general support for using a range of commonly available “second chance” mechanisms that also extended to offenders convicted of both violent and non-violent offenses. Levels of support significantly varied by race, gender, and age. There was significantly more support for using certain mechanisms in response to the trafficking of serious drugs, which was fully mediated by participants’ views on the importance of the cost of incarceration.

Conclusions

Members of the public appear open and supportive to utilizing “second chance” mechanisms in a variety of contexts. Yet the cost of incarceration to taxpayers appears to particularly motivate increased public interest in using such mechanisms for offenders convicted of the trafficking of serious drugs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the last half century, the prison population in the USA has grown by almost 500% and represents the world’s highest incarceration rate (Cullen et al., 2012; Sabol et al., 2009). Although the imprisonment rate in 2019 marked a 17% decrease from the prior decade (Carson, 2020), the downward trend in incarceration observed in the last 10 years is still not nearly at the pace required to address the USA’s problematic reliance on long-term prison sentences (Austin et al., 2016). Yet as laws and views have changed, it is now widely acknowledged that prison terms of many individuals serving long-term sentences can be and often are excessive, unjust, and out-of-line with societal views on sentencing practices (Barry et al., 2020; Mauer, 2018). Yet, to date, there has been inadequate action in enacting mechanisms that reconsider and alleviate long-term sentences of those currently incarcerated (Fair and Justice Prosecution Working Group, 2020; Landsman, 2019; Mauer, 2018). Enacting mechanisms for the release of those serving such sentences will likely require “political will” from policymakers and legislators, stemming from public support for such policies (Renaud, 2018).

The current study, using a randomized experimental design with a national sample of US adults, provides an empirical examination into popular support for mechanisms that provide early release and “second chances” for people serving long-term prison sentences. Specifically, this study looks into three lines of inquiry that extend and expand upon existing public opinion data on these issues. First, this research examines levels of public support for a range of different “second chance” mechanisms used to achieve early release from long-term prison sentences, as well as if demographic characteristics of the public may be predictive of such support. Second, this work examines if and how public support for different “second chance” mechanisms may vary for those convicted of different offenses that have resulted in long-term incarceration. Finally, this study examines if and how the public’s views on different factors known to be connected to general popular support for “second chances” (i.e., cost, public safety, racial bias) act as underlying mechanisms that help to explain varying levels of public support for “second chance” mechanisms observed for different types of offending. Ultimately, takeaways and implications of these findings for policy are also discussed.

Long-term prison sentences in the USA

There are many reasons for why the US prison population has been and currently is the largest in the world. One of the chief factors has been a reliance on harsher sentencing practices with the objective of reducing crime and correspondingly improving public safety outcomes (Simon, 2014; Western, 2006). Violent crime rates increased by 270%, peaking in 1991, from the 1960s to 1990s (Austin et al., 2016). In response, state and federal lawmakers across the country started to increase the length of prison stays with policies, such as mandatory minimums, “three strikes” sentence enhancements, and truth-in-sentencing laws, that attempted to affect crime rates, recidivism, and violence through a mix of deterrent and incapacitating sentencing measures (Mauer, 2018). Such draconian sentencing laws, resulting in a philosophy based upon “extreme penology” and “total incapacitation” (Simon, 2014), have resulted in significant increases in offenders’ length of stay in prison across both violent and non-violent crimes (Austin et al., 2016). At present, 200,000 people incarcerated in state prisons are serving life or “virtual” life sentences of more than 50 years, with those spending more than 10 years in prison tripling between 1999 and 2015 (Nellis, 2017; United States Department of Justice, 2018).

Given our reliance on harsher sentencing laws, the question has become whether increased lengths of stay have achieved their purported goals of reducing crime and increasing public safety. Although crime rates have dramatically declined since the 1990s, large-scale and longitudinal empirical research has suggested that increased sentence lengths and mass incarceration has played an extremely limited role in reducing and deterring crime (see Roeder et al., 2015). Factors thought to substantively contribute to the crime decline have include a variety of social and economic factors, including policing and community-based crime reduction strategies, decreasing drug markets, and increased economic opportunities and mobility (Mauer, 2018). Although some literature has found that the use of sentencing strategies resulting in long-term incarceration may have resulted in 25% of the crime decline in the last 30 years, a larger body of research has found the effect to be closer 5% of the crime decline (Levitt, 2004; Spelman, 2000; Western, 2006). Although there is likely some relationship between increased incarceration and lower crime, locking up additional people has not been considered an effective crime control strategy given the economic and human cost of incarceration (Cullen et al., 2000; Gottschalk, 2013; Mauer, 2018; Raphael & Stoll, 2014; Roeder et al., 2015; Travis et al., 2014).

Empirical research has also suggested that the consequences of long-term incarceration result in “diminishing returns” to public safety, with long-term prison terms often keeping individuals incarcerated far past the point that they still pose a potential risk to public safety (Austin et al., 2016; Cullen et al., 2000; Mauer, 2018; Western, 2006). For example, research has found that prison stays longer than 20 months have “close to no effect” on reducing overall recidivism upon release (Kuziemko, 2013). Other studies show that long prison terms often have criminogenic effects that can lead to the commission of future offenses (Gaes & Camp, 2009). Prisons often do not have or provide rehabilitative programming generally, and particularly to those are serving long-term sentences, and release individuals without appropriate economic and social support; this unfortunately makes them more susceptible to being involved in criminal prior activities (Austin et al., 2016). Unsurprisingly, in part due to criminogenic effects, the majority of US prisoners are reincarcerated within 3 years (Durose et al., 2014).

Reconsidering long-term prison sentences of those currently incarcerated

Based on existing research, there has been increasing recognition that the current sentencing regime and reliance on long-term incarceration may be unnecessary; not only is it both unjust and harmful to communities, and particularly to communities of color, but the human and monetary costs, and collateral consequences, of long-term sentences are not proportionate to their minimal effects on crime rates and public safety (Austin et al., 2016; Fair and Justice Prosecution Working Group, 2020; Gottschalk, 2013; Raphael & Stoll, 2014; Roeder et al., 2015; Travis et al., 2014). In turn, this has led to increased reform efforts to roll back draconian sentencing laws at both federal and state levels, particularly by reducing the amount (e.g., sentencing alternatives) and length (e.g., revised downward sentencing guidelines) of prison admissions as a means of reducing prison populations (Mauer, 2018; Nellis, 2017). Thus, the USA has entered a new policy era in which downsizing the nation’s prison population has achieved a tangible level of bipartisan political support nationwide (Aviram, 2015; Cullen et al., 2014; Gottschalk, 2015; Petersilia & Cullen, 2014).

However, even if reforms begin to scale back sentence lengths and the use of long-term incarceration in the future, hundreds of thousands of people still remain in prison serving long-term sentences (Mauer, 2018). Indeed, truly addressing mass incarceration does not just mean reducing contemporary prison admissions but requires reconsideration of those that are already behind bars (Clear & Austin, 2009; Pfaff, 2017). In order to ensure that our policies encourage public safety, monetary responsibility, and justice, we must actively reconsider punishments of those who are already incarcerated and options for their release (Fair and Justice Prosecution Working Group, 2020; Renaud, 2018).

In addition to their minimal effects on crime rates and public safety, there are a multitude of other reasons that suggest the need to reconsider long-term prison stays of those currently incarcerated. Evidence at both state and federal levels demonstrates that it is possible to reduce prison populations without negatively affecting public safety (Mauer, 2018). Over the last decade, almost 30 states have reduced both imprisonment and crime rates at the same time, including New Jersey, New York, and Texas (Durose et al., 2014; Eisen & Cullen, 2016). A study by the U.S. Sentencing Commission found that recidivism rates were nearly identical between individuals who received sentence reductions as a result of retroactive changes to federal sentencing laws and those who served full sentences prior to sentencing changes (Hunt et al., 2018). Communities of color have been also been known to be unduly affected by long-term incarceration, and modes of early release have been thought to potentially provide strategies for tackling racial inequalities in sentencing (Eaglin & Solomon, 2015; Snyder, 2015).

There is also evidence that many individuals currently serving long-term prison sentences have “aged out” of criminal behavior and/or are at low risk of committing future crimes. For the majority of both violent and non-violent crimes, arrests peak in the late teens or early 20s, followed by steep drop-offs (Snyder, 2012). Between 1999 and 2016, the number of individuals over age 55 in state prisons increased by 280% (McKillop & Boucher, 2018). The number of individuals in US prisons over the age of 55 is likely to continue to increase, as one out of seven people in US prisons is serving either a life or a “virtual life” sentence (The Sentencing Project, 2018). Keeping aging, low-risk individuals in prison is expensive and harms public safety by diverting resources away from effective crime-prevention strategies (Elliott & Fagan, 2017; Kelly, 2015). Indeed, among 45 states, the average annual cost of incarceration per inmate is more than $33,000 and more than $50,000 for some states (Mai & Subramanian, 2017).

Long-term prison terms also undermine the supposed rehabilitative purpose of incarceration and ignore the capacity to change (Clear, 2008). Hopwood (2019) argues that many people can and often do change in prison, demonstrating that they often merit “second chances” because they are rehabilitated. Yet without real opportunity for release, people can lose hope and lack incentive to do the “work” of rehabilitation and take positive steps toward re-entering the community (Petersilia, 2003). Thus, strategies that allow long-term sentences to be reassessed or provide early release allow punishment to be amended in order to reflect if and how individuals have changed or become rehabilitated since initial sentencing (Fair and Justice Prosecution Working Group, 2020).

Finally, hundreds of thousands of people are serving sentences that are out-of-step, disproportionate, and extreme with regards to both international sentencing practices and contemporary sentencing norms in the USA (Mauer, 2018; Petteruti & Fenster, 2011). Many individuals are still serving lengthy sentences that were products of sentencing policies that have since been repealed, but are not retroactive (Renaud, 2018). For example, second degree robbery was considered a “strike” under Washington’s “three strikes” law until 2019; however, the current law was not amended to retroactively apply to those currently in prison under such circumstances (Associated Press, 2019). The Fair and Justice Prosecution Working Group (2020) writes that “while someone with two strikes who commits second degree robbery today would be sentenced to less than seven years, 62 individuals remain sentenced to life without parole because they received a strike for second degree robbery” (p. 7) before 2019.

“Second chance” mechanisms for early release

As evidence suggests that individuals sentenced to long-term sentences do little to advance justice and provide deterrence, there have been many recent calls for using and expanding existing opportunities for early release of those currently serving long-term sentences (e.g., Beckett et al., 2018; Hatheway, 2017; Hopwood, 2019; Mauer, 2018; Renaud, 2018). As it stands, a variety of strategies exist, which are often jurisdiction specific at state and federal levels, that policymakers can employ as strategies for early release by which a person’s time served can be shortened in order to alleviate long-term prison stays.

As detailed by the Prison Policy Initiative, these “second chance” mechanisms fall into eight strategies that help to make people eligible for early release via parole faster, make it more likely that parole will be granted, curtail time served irrespective of sentencing and parole decisions, and ensure that people do not return to prison for technical reasons (see Renaud, 2018). The first strategy, presumptive parole, is a system in which incarcerated individuals are released upon first becoming eligible for parole unless the parole board finds explicit reasons to not release them. This counters the traditional approach, in so that release on parole is the expected outcome, rather than something that must be justified. Second look sentencing, the second strategy, allows a case to be brought back into court for a judge to consider reducing the sentence; for example, the “second look” provision of the Model Penal Code (in § 305.6) authorizes prisoners the right to apply to a judicial panel or decisionmaker for potential modification of their original sentence after serving 15 years behind bars (The American Law Institute, 2017). Third, the granting of good time, allows people to earn time off their sentences by avoiding disciplinary infractions and participating in prison programming, with the idea that good time credit incentivizes people to engage in behaviors that support rehabilitation.

Fourth, universal parole eligibility after 15 years, uses sentencing structures that presume that individuals and society transform over time and ensures that people do not serve more than 15 years without being considered for parole. The fifth strategy, retroactive application of sentence reduction reforms, ensures that recent legislative changes that roll back mandatory minimums, “three strikes” laws, and other punitive laws are retroactive, ensuring that people who are currently incarcerated also receive the benefits of new thinking about sentencing. Sixth, parolees are often returned to prisons because of “technical violations,” such as missing a meeting with a parole officer or traveling to another state without permission, rather than indication that they represent a threat to public safety. Elimination of parole revocations for technical violations helps to keep people from returning to prison for minor violations, which may indicate that a person on parole needs more assistance and not more incarceration. Seventh, compassionate release shortens sentences when circumstances, such as age or health, reduce the need for imprisonment. The eighth strategy, commutation, reduces sentences by releasing someone from prison or making someone eligible for release earlier; these decisions are usually made by governors.

Renaud (2018) suggests if federal and state systems are serious about undoing reliance on mass incarceration and revisiting long-term prison sentences, we must be willing to “leaven retribution with mercy” (p. 7), and state and federal leaders must be willing to use existing “second chance” mechanisms, as well as expand existing opportunities. Yet, even with mounting bipartisan support surrounding criminal justice reform, there has been little action with regards to increasing the use of “second chance” mechanisms as ways to relieve long-term prison sentences (Barry et al., 2020; Mauer, 2018; Renaud, 2018). These existing strategies, although varying by jurisdiction, are vastly underused at both state and federal levels; in many cases, these mechanisms are either available or implementable, but there has not yet been necessary “political will” to use or expand the use of such mechanisms (Renaud, 2018).

US public support for “second chance” mechanisms

Petersilia and Cullen (2014) argue that our opportunity to move away from the current reliance on long-term incarceration may well be squandered by political inaction unless we use and expand the use of mechanisms that would alleviate such a burden. Yet literature suggests that support of the US public for “second chance” mechanisms may help to spark such action and “political will” of political and policy leaders. Public support and opinion is thought to be a “drive wheel” of criminal justice practice and policy (Pickett, 2019). Leaders and policymakers at all levels of government, over fears of reelection or public fallout, often respond to public opinion and support when implementing criminal justice policy, and “follow the lead” of popular support when it comes to criminal justice reform if an issue is significant to the public and demonstrated to be in line with popular attitudinal trends (Canes-Wrone et al., 2014; Enns, 2016; Erikson et al., 2002; Jennings et al., 2017; Stimson, 1999).

Public opinion not only facilitates policy formation, but also places limits on what initiatives may be politically feasible (Moran, 2001; Wood, 2013). This suggests that when members of the public are overwhelmingly supportive of punitive sentencing measures, policymakers are unlikely to utilize strategies that are non-punitive. Indeed, empirical literature has shown that public support for punitiveness in sentencing may have profoundly determined the expansion of imprisonment and sanction severity in the USA over much of the last five decades (Baumer & Martin, 2013; Enns, 2014; Garland, 2012; Jacobs & Kent, 2007; Useem et al., 2003; Useem & Piehl, 2008) and offers a framework for understanding why political leaders have historically advanced punitive sentencing strategies (Blumstein et al., 2005; Enns, 2014). From the 1960s to 1990s, swings in public punitiveness heralded swings in legislative and congressional attention to criminal justice issues (Jones & Baumgartner, 2005; Shapiro & Page, 1992). During this time, polls showed an 25% increase in public support for more stringent sentencing practices (to above 80%) (Cullen et al., 2000; Ramirez, 2013; Shapiro & Page, 1992). Public punitiveness also appeared to directly influence incarceration through the enactment of ballot initiatives (i.e., “three strikes” laws) during this time (Enns, 2014; Gibson, 1997; Gordon & Huber, 2009). Referring to policies resulting in long-term incarceration, Tonry (2004) states that “ordinary Americans made these things happen. Elected politicians proposed policies and enacted laws, but they would not have done it if they believed voters would disapprove” (p. 1).

Yet, recent evidence suggests that public support, to some extent, has shifted away from long-term prison sentences. Ramirez (2013), tracking a number of national polls from 1994 to 2013, found a decline in public support for punitive sentencing practices and long-term incarceration, with support for longer sentencing lengths dropping around 23% from 85 to 62% during that 20-year period. The shift away from a dominant focus on punitiveness in sentencing also appears, at least to a degree, to be bipartisan. A recent poll by the American Civil Liberties Union estimated that more than 70% of Americans (87% of democrats, 57% of republicans) agree that it is important to reduce the prison population because there is little utility to many long-term prison sentences (ACLU, 2017).

Recent data have also showed at least moderate public support for the early release of and alternatives to prison for some offenders, particularly those that are convicted of non-violent crimes, in order to avoid incarceration (e.g., Pew Charitable Trusts, 2014; Public Opinion Strategies and The Mellman Group, 2012; Sundt et al., 2015; Thielo et al., 2016). In fact, a recent poll found 69% of a large sample of US voters (81% of democrats, 64% of republicans) voiced bi-partisan support for laws that allow for the re-examination of old sentences in order to potentially provide long-term incarcerated offenders “second chances” (Barry et al., 2020). Bipartisan public support for “second chances” was found to be connected to many factors, with the most prominent being beliefs that US sentencing is too costly and wastes taxpayer dollars, extreme by international standards, racially discriminatory, often out-of-step with current views on and practices in sentencing, and that many individuals currently incarcerated are unlikely to be a public safety threat if released (i.e., because of age, rehabilitation, etc.) (Barry et al., 2020).

Overall, recent evidence suggests that utilizing mechanisms for early release from long-term prison sentences in order to provide offenders their “second chances” may be a salient issue within public sentiment and at least moderately consistent within popular attitudinal trends (Burstein, 2014; Krimmel et al., 2012; Stimson, 1999, 2004). As such, politicians and policymakers may be in the best position yet to “move policy in a less punitive direction” (Ramirez, 2013, p. 1006) by considering their use.

Current study

The current study, using an experimental design with a national sample of US adults, provides a detailed empirical inquiry into popular support of the US public for “second chance” mechanisms that provide reconsideration and early release from long-term prison sentences. Although data suggest that many members of the public are generally supportive of providing “second chances” to individuals who are currently long-term incarcerated, such data are limited in scope and depth, and questions still remain with regard to public support of “second chance” mechanisms. In order to potentially help “spark” the political action of policy leaders in using and expanding the use of “second chance” mechanisms, a more nuanced understanding on public support of these issues is needed (Barry et al., 2020; Renaud, 2018). The current study aims at examining three lines of inquiry that extend and expand upon existing data.

First, although existing data indicate many members of the public are supportive of giving some offenders “second chances,” such data does not tell us about their levels of support for individual “second chance” mechanisms. As discussed above, Renaud (2018) details the common availability of at least eight strategies that can act as “second chance” mechanisms. This information is particularly important, as available mechanisms vary widely based on the jurisdiction, and states vary in many ways in how they structure eligibility for the use of such mechanisms (Renaud, 2018). Further, although polls suggest a level of bipartisan public support for providing “second chances,” levels of public support for the use of different mechanisms could be affected by ideological, geographic, or other demographic backgrounds. Thus, it is not only important for politicians and policymakers to know which mechanisms are popular with the public and members of their own constituency in jurisdictions that have different mechanisms available, but also who is more likely to support their use with regard to implementation and when tailoring suggested reforms. This study examines public support across eight common strategies used as “second chance” mechanisms, and if and how demographic factors may be predictive of their support.

Second, existing evidence indicates at least moderate levels of public support for “second chances,” but does not specify if this support extends to all offenders. Indeed, as compared to their general support for such strategies, the public may not extend the same levels of support to the early release of those incarcerated for certain offenses. Currently, almost 58% of the total prison population is incarcerated for six major offenses (Austin et al., 2016). Three of these offenses are non-violent (serious burglary, non-violent weapon offenses, trafficking of serious drugs), while three are violent (murder, aggravated assault, robbery). Literature already suggests that the public may feel differently about considering the early release of those convicted of violent offenses and their return to communities (Applegate et al., 1996; Austin, 1986; Petersilia, 2001). As such, the public might be more hesitant in providing “second chances” to those convicted of violent offenses, or that certain “second chance” mechanisms may be considered better strategies for those convicted of either violent or non-violent offenses. Thus, this study examines if and how public support for “second chance” mechanisms may vary for those convicted of different types of offenses that have resulted in long-term incarceration.

Finally, if public support for specific “second chance” mechanisms does indeed vary for particular offenses, factors that underlie these different levels of support may not be one-size-fits all. Poll data from Data for Progress suggest that general public support for “second chances” from long-term incarceration appears to be connected to public views on and their weight given to a range of factors, including beliefs that US sentencing is extreme by international standards, racially discriminatory, too costly, out-of-step with current views/values, and continues to incarcerate those that do not pose a risk to public safety (Barry et al., 2020), but does not account for how these factors motivate support in different contexts or for different offenses. Thus, this study tests if and how factors known to motivate the public’s general support for “second chances” may underlie varying public levels of support for “second chance” mechanisms observed across different offending contexts. Specifically, in order to examine if and how different factors may motivate levels of support for “second chance” mechanisms observed for different types of offenses, mediation models are calculated in order to examine underlying mechanisms for any significant main effects observed in the second line of inquiry noted above. As no particular factor has been previously discussed as the dominant influence for general public support for “second chances” from long-term incarceration (Barry et al., 2020), there were no specific hypotheses associated with these mediation models.

Method

Participants

The target population was a national sample of US adults (age 18+) demographically balanced on gender, race, education, income, and geography. The sample was requested from Qualtrics Panel, who secured a sample that was balanced on quotas (gender, race, education, income, geographic region) that match the demographic breakdown of population of adults in the USA. An a priori power analysis (accounting for covariates in models and using f = 0.20, alpha = 0.01, power = 0.99, df = 6, for 7 groups) indicated that a sample of around 833 respondents (119 per condition) would be sufficient and was requested from Qualtrics Panel. A total of 237 participants were eliminated during data collection as they did not finish the survey after starting it (145 participants) or because they did not answer check and/or honesty questions correctly (92 participants). Participants were paid by Qualtrics Panel.

Study design and procedure

The current study used a randomized experimental design with seven cells in order to provide an empirical inquiry into popular support of the US public for “second chance” mechanisms. Participants were first asked to provide informed consent. Basic demographics, including age, race, gender, geographic location, income, and education were collected at the beginning of the survey to screen participants for representativeness quotas. The study lasted about 20 minutes. Honesty and attention questions were also asked to ensure the quality of the data, and participates who did not correctly answer those questions were automatically excluded from participation in the middle of the study. Study stimuli were pretested before data were collected. A pilot of about 50 participants was conducted to ensure readability and that there were no discrepancies with data quality. This study received approval from the author’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). Data was collected in mid-2020.

Stimuli design

After providing consent and basic demographics, participants were randomly presented with one of seven descriptions about incarceration in the USA (a control condition or one of six experimental conditions). In the control condition, participants were randomly presented with a brief description of overall incarceration in the USA (which included total number of prisoners incarcerated at both state and federal levels, average length of stay and rate of recidivism, number of prisoners serving sentences over 10 years). The control acted as a way to measure general support for “second chance” mechanisms, regardless of specific offense, as well as a reference which to compare to experimental conditions.

In the experimental conditions, participants were randomly presented with a brief description of incarceration in the USA for one of six crime categories (which included a brief definition of the crime itself, the number of US prisoners incarcerated for that crime, percentage of national prison population incarcerated for that crime, average length of stay/years served for that crime, average likelihood of recidivism for that crime). The six crime categories included serious burglary, robbery, murder, trafficking of serious drugs, non-violent weapons offenses, and aggravated assault. These crimes, identified by Austin et al. (2016), were chosen to be included in this research because cumulatively they lead to the incarceration of the largest total number and percentage of prisoners in the USA, and their lengths of stays increased significantly between 1993 and 2009 (Bonczar et al., 2011). Descriptions and statistics for both the control and experimental conditions on incarceration in the USA generally and for each specific crime were adapted from Austin et al. (2016)’s report. All descriptions are available upon request, but an example of one of the descriptions (that of murder) is provided here:

Murder (165,000 prisoners, 11.3 percent of national prison population): Murder is the intentional killing of another person, or killing of a person during a felony; it is planned, intentional, or committed in the course of a planned or intentional felony crime. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 11% of those released after a murder conviction were imprisoned for a new crime within three years. The average years served for murder is estimated at 11.7 years.

Response variables

Regardless of variations in their stimuli, all participants were asked to rate, on a sliding scale from 1 to 100 (with labels as 1 (strongly oppose) to 25 (oppose) to 50 (neutral) to 75 (support) to 100 (strongly support)), how much they supported the use of each of eight different “second chance” mechanisms, identified by the Prison Policy Initiative, in relation to the description/for the specific offense provided to them. These included (1) presumptive parole, (2) second look sentencing, (3) the granting of good time, (4) universal parole eligibility after 15 years, (5) retroactive application of sentence reduction reforms, (6) elimination of parole revocations for technical violations, (7) compassionate release, and (8) commutation. Descriptions provided to participants for each “second chance” mechanism were directly patterned from the Prison Policy Initiative (see Renaud, 2018) and can be found in Table 1. To ensure that participants read the descriptions, each mechanism was presented on a separate page with a forced 30s timer that prevented participants from moving on in the survey before 30s.

On a sliding scale from 1 to 100 (with labels as 1 (not at all important) to 50 (neutral) to 100 (completely important)), all participants were also asked to rate the importance of five different beliefs, or factors, in their support for the use of “second chance” mechanisms in relation to the description/for the specific offense provided to them. These factors are those that have been indicated in existing poll data by Data for Progress as reasons that drive general public support of laws that consider and provide “second chances” (Barry et al., 2020), including the following: (1) The original prison sentence is extreme by international standards; (2) the original prison sentence was excessive as compared to other offenders who have committed this crime because of race-based policies or racial bias; (3) the original prison sentence is too costly and wastes taxpayer dollars; (4) the individual who has been incarcerated is either no longer or unlikely to be a threat to public safety (i.e., because of age, rehabilitation, etc.); and (5) the original prison sentence is unfairly out-of-step with current views/values on or practices in sentencing. The use of these factors and their descriptions were inspired by Barry et al. (2020).

Finally, a short series of other general attitude measures that were unrelated to the current experiment, but which examined some participants’ general views on factors considered by parole boards and length of stay reductions, were collected at the end of the survey as a part of a larger project. Those measures are not reported here. All materials and measures are available upon request.

Demographic and control variables

Basic demographics, including age (continuous variable), race (five categories: White non-Hispanic, Black/African-American, Hispanic, Asian, other), gender (two categories: male = 0, female = 1), education (seven categories: high school graduate or less; some college; associate’s degree; bachelor’s degree; master’s degree; doctoral degree; professional degree), income (six groups: available upon request), and religiosity (two categories: identifies as religious = 1, does not identify as religious = 0), were collected from all participants. Income and education were found to be collinear in regression analysis, which is common as they are often highly correlated (Liverani et al., 2016), and education was chosen as the variable used in the models as it has been more significantly connected to punitiveness in some previous work (Brown, 2006; Costelloe et al., 2009). Geographic location was also measured (four categories: south, west, midwest, northeast).

Variables measuring political orientation and participation were also collected, including political party (five categories: republican, democratic, independent, none, other), political ideology (continuous from extremely liberal (0) to extremely conservative (7)), and whether they voted in their last local election before (two categories: yes = 1, no = 0). Finally, as previous literature has suggested that long-term prison sentences may bring solace or justice to victims (Roberts, 2009), previous victimization of one’s self or loved ones, of any crime (two categories: yes = 1, no = 0) and of violent crimes (two categories: yes = 1, no = 0), was also measured of participants.

Two further scales, used in their entirety from Call and Gordon (2016), were also administered in order to control for general punishment orientations in two areas. All questions used a 1 (definitely not) to 100 (definitely yes) scale in response to the query of whether each item was the best way to reduce crime. The Traditional Punishment Philosophy Scale resulted in an averaged composite score of seven items (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.77). Higher ratings indicated agreement with traditional punishment philosophies (deterrence, retribution, incapacitation). The Rehabilitative Punishment Philosophy Scale resulted in an averaged composite score of seven items (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86), with higher ratings indicating agreement with rehabilitative punishment philosophies (rehabilitation, restoration).

Results

Regression analyses were adjusted for multiple tests by adjusting p-values for the number of hypothesis tests performed via the Bonferroni correction.

Demographics

A total of 836 participants completed the sample (119 participants per experimental condition; based on Qualtrics sampling procedure, oversampling of three participants resulted in 122 participants in the control condition). Demographic and control variables of the sample are in Table 2. Information on income is available upon request. Analyses revealed no significant demographic differences across cells.

Main results

Descriptive statistics of participants’ support for the eight “second chance” mechanisms and their ratings on the importance of five different factors to their support for the use of “second chance” mechanisms, across offense type and regardless of offense (control condition), are in Tables 3 and 4.

Support for “second chance” mechanisms

First, a one-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used to see if general support for “second chance” mechanisms (participant ratings in the control condition) at all differed by the specific mechanism. Results showed no significant differences in participants general support for “second chance” mechanisms by specific mechanism in the control condition (F(7, 847) = 0.777, p = 0.607).

In order to examine how support for each of the eight “second chance” mechanisms may deviate from general levels of support (control condition) depending on the offense category specified as the reason for long-term incarceration (six experimental conditions), main effects were estimated using linear regression models that regressed the offense type on support for the use of each “second chance” mechanism. This resulted in eight models (for each “second chance” mechanism). Each model included both demographic and other control variables (two scales on general punishment), which not only controlled for these variables in each model, but also allowed for the examination of how demographic characteristics of respondents predicted their levels of support for each “second chance” mechanism.

Model statistics, regression coefficients (standardized and unstandardized, as well as standard errors), and p-values are presented in Table 5. As seen in Table 5, there were significant main effects of trafficking of serious drugs, as compared to the control, on significantly more support for elimination of parole revocations for technical violations (model 3), “second look” sentencing (model 5), granting of good time (model 6), and retroactive application of sentence reduction reforms (model 8).

Three demographic variables also consistently predicted participant support for different “second chance” mechanisms (see Table 5). Being Female predicted significantly less support for presumptive parole (model 1), universal parole eligibility after 15 years (model 2), elimination of parole revocations for technical violations (model 3), commutation (model 4), “second look” sentencing (model 5), granting of good time (model 6), and compassionate release (model 7). Age negatively predicted support, in a linear fashion, for presumptive parole (model 1), universal parole eligibility after 15 years (model 2), elimination of parole revocations for technical violations (model 3), commutation (model 4), “second look” sentencing (model 5), granting of good time (model 6), and retroactive application of sentence reduction reforms (model 8). Being Black predicted significantly more support for presumptive parole (model 1), universal parole eligibility after 15 years (model 2), commutation (model 4), “second look” sentencing (model 5), granting of good time (model 6), compassionate release (model 7), and retroactive application of sentence reduction reforms (model 8).

Participants’ rehabilitative punishment orientation significantly predicted more support for all eight “second chance” mechanisms (models 1–8), while traditional punishment orientation predicted less support for compassionate release (model 7). Finally, other demographics also predicted support for singular mechanisms. Being from the South predicted less support for commutation (model 4), having an associate’s degree predicted significantly more support for elimination of parole revocations for technical violations (model 3), and having a more liberal political ideology predicted more support for commutation (model 4).

Mediation results

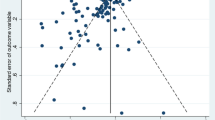

In order to examine underlying mechanisms for significant main effects observed the first part of the analysis, mediation models were calculated. Three separate regression equations identified if and how main effects for the offense type (independent variable) on participants’ support for each “second chance” mechanism (outcome variables) were mediated by their ratings on factors they believed to be important to their support of “second chance” mechanisms (mediator variable). Full mediation was determined by four conditions (see Baron and Kenny, 1986): (1) the offense type significantly affected participants’ support for “second chance” mechanisms (path C; see Table 5 and results above); (2) the offense type significantly affected ratings of the mediator variable in the first equation (path A; see Table 6, controlling for demographic variables); (3) the mediator variable significantly affected support for “second chance” mechanisms in the third equation (path B; see Table 7, controlling for offense type; including demographic variables did not significantly affect results); and (4) path C became insignificant when the mediator variable was included in the regression equation (path C’). Results are reported from mediation analyses in which all four conditions held, resulting in four mediation models detailed below and illustrated in Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4.

The main effect of trafficking of serious drugs on significantly more support for the elimination of parole revocations for technical violations was mediated by participants’ increased ratings on the importance of the offender’s original prison sentence being too costly. As shown in Fig. 1, trafficking of serious drugs both increased support for the elimination of parole revocations for technical violations (path C; see Table 5) and ratings on the importance of the offender’s original prison sentence being too costly (path A; see Table 6). The pathway between ratings of the importance of the offender’s original prison sentence being too costly and elimination of parole revocations for technical violations is significant (path B; see Table 7). Including the importance of the prison sentence being too costly in path C results in non-significance (path C’: b = 3.23, SE = 3.19, B = 0.032, t = 1.04, p = 0.300).

The main effect of trafficking of serious drugs on significantly more support for “second look” sentencing was also mediated by participants’ increased ratings on the importance of the offender’s original prison sentence being too costly (see Fig. 2). Trafficking of serious drugs increased both support for “second look” sentencing (path C; see Table 5) and ratings on the importance of importance of the offender’s original prison sentence being too costly (path A; see Table 6). The pathway between ratings of the importance of the offender’s original prison sentence being too costly and “second look” sentencing is significant (path B; see Table 7). Including the importance of the original prison sentence being too costly in path C results in non-significance (path C’: b = 4.75, SE = 2.73, B = 0.049, t = 1.74, p = 0.082).

Similar to the previous two models, the main effect of trafficking of serious drugs on significantly more support for granting of good time was mediated by participants’ increased ratings on the importance of the incarcerated individual no longer being a threat to public safety. As shown in Fig. 3, trafficking of serious drugs increased both support for granting of good time (path C; see Table 5) and ratings on the importance of the importance of the offender’s original prison sentence being too costly (path A; see Table 6). The pathway between ratings of the importance of the importance of the offender’s original prison sentence being too costly and granting of good time is significant (path B; see Table 7). Including the importance of the original prison sentence being too costly in path C results in non-significance (path C’: b = 4.97, SE = 2.79, B = 0.051, t = 1.78, p = 0.075).

Finally, the main effect of trafficking of serious drugs on significantly more support for the retroactive application of sentence reduction reforms was once again mediated by participants’ increased ratings on the importance of the offender’s original prison sentence being too costly (see Fig. 4). Trafficking of serious drugs increased both support for the retroactive application of sentence reduction reforms (path C; see Table 5) and ratings on the importance of the offender’s original prison sentence being too costly (path A; see Table 6). The pathway between ratings of the importance of the offender’s original prison sentence being too costly and retroactive application of sentence reduction reforms is significant (path B; see Table 7). Including the importance of the original prison sentence being too costly in path C results in non-significance (path C’: b = 1.14, SE = 2.84, B = 0.012, t = 0.40, p = 0.699).

Discussion

The current study helps to provide multifaceted data into US popular support for “second chance” mechanisms that can provide reconsideration of and early release from long-term prison sentences. By extending and expanding upon existing public opinion data, these results illuminate three main takeaways areas, in response to its three lines of inquiry, surrounding public support for “second chance” mechanisms. Following discussion of these three takeaways, implications will be discussed.

First, as existing evidence does not indicate levels of popular support for individual, commonly available “second chance” mechanisms, this study provides data to show stable, moderate support for all eight “second chance” mechanisms. For those rating their general support (control) for the use of such mechanisms, average ratings of support were all above neutral (50), and between neutral (50) and support (75) on the rating scale for each “second chance” mechanism. Further, average ratings for the general use of “second chance” mechanisms did not significantly differ based on the mechanism, conveying consistent levels of general support for these mechanisms regardless of the mode.

Although support for the general use of “second chance” mechanisms did not significantly differ based on the mechanism, participants’ ratings of support, as well as the average ratings of support across all conditions, for “second chance” mechanisms do descriptively indicate that the granting of good time was the highest-rated “second chance” mechanism. For some crime categories, such as trafficking of serious drugs and serious burglary, participants’ support for its use even surpassed 70 on the given rating scale. The fact that the granting of good time appears attractive to members of the public may be related to its underlying goals; unlike other “second chance” mechanisms, granting of goodtime is the only mechanism in which an incarcerated individual’s good behavior or participation in rehabilitative programming is explicitly mentioned as a contributing factor to his or her early release (Renaud, 2018). Indeed, good time credit is supposed to incentivize people to engage in prosocial behaviors in order to gain early release, which may lead participants to believe someone is more deserving of early release (O’Hear, 2014). This could be a contrast to support for modes like Universal Parole Eligibility after 15 years, which descriptively was the lowest-rated mechanism with regard to its general use and across all conditions; through this mode, people do not necessarily “earn” the opportunity for early release directly through their own prosocial behaviors, but instead through legislatively structured eligibility that applies to all prisoners, regardless of their stake in their own rehabilitation.

Levels of public support for “second chance” mechanisms do appear to vary based on certain demographic factors. Particularly, observing patterns of support across individual “second chance” mechanisms, three demographic factors consistently predicted levels of support across almost all “second chance” mechanisms: age, gender, and race. Increasing age strongly predicted less support for seven of the examined mechanisms, which complements previous literature suggesting more punitive attitudes as one ages (e.g., Applegate et al., 2002; Frost, 2010; King & Maruna, 2009; McCorkle, 1993; Payne et al., 2004). Previous work has suggested that the relationship between advancing age and punitiveness may be associated with fears associated with potential victimization due to increased vulnerability ( “vulnerability hypothesis”) (Armborst, 2017; Pratt, 2000; Stack, 2000). This might suggest that older US adults could also be less supportive of “second chance” mechanisms in part due to fears that they may be victimized by offenders returning to the community via these modes of early release. Future work should not only attempt to replicate this trend but also assess whether the “vulnerability hypothesis” may help to explain the negative relationship between age and support for “second chance” mechanisms.

Being female also significantly predicted less support for seven of the “second chance” mechanisms. At first potentially, this may appear counterintuitive to existing research, as substantial literature indicates that males are generally more punitive than females in terms of support for punishment, such as support for the death penalty and less options for offender rehabilitation (e.g., Applegate et al., 2002; Cochran & Sanders, 2009; Cullen et al., 1985; Falco & Turner, 2014; Kury & Ferdinand, 1999). However, these studies have generally gauged support for practices resulting in or related to administering punishment, rather than processes or mechanisms that release prisoners back to the community. Instead, research that has assessed gender as it relates to reconsidering sentences or early release from prison has found that women are often not as supportive of such measures as men (Dodd, 2018; Estrada-Reynolds et al., 2016; O’Hear & Wheelock, 2015). For example, Haghighi and Lopez (1998) found that females were significantly more likely to oppose reducing offenders’ prison sentences, conditionally releasing those with serious criminal records, and granting early release due to good behavior. Similar to age, this previous work suggests that men and women may take different views on reconsidering sentences and early release because they experience different emotions when thinking about these issues, and particularly, potential anxiety and fear of crime or victimization if offenders are returned to the community (Dodd, 2018). Thus, future work should also examine the “vulnerability hypothesis” in relation to female support for “second chance” mechanisms.

As a contrast to age and being female, being Black predicted significantly more support for seven of the “second chance” mechanisms, which complements previous literature suggesting that being Black significantly predicts less punitiveness in criminal justice contexts as compared to Whites and even other minorities (Miller et al. 1986; Bobo & Johnson, 2004; Johnson, 2008; Costelloe et al., 2009). Recent poll data from the Pew Research Center suggest that these views of Black Americans not only extend to less punitive views on sentencing, but also more support for parole and release from incarceration, as compared to White Americans (Horowitz et al., 2019). That data and other research has suggested that Black Americans’ attitudes toward punishment-related policies may be largely tied to views about racial discrimination and bias in the administration of the criminal justice system, including police interactions, sentencing, incarceration, and parole, and beliefs that Black Americans often received disproportionately punitive treatment by the legal system leading to harsher sentences; reduced punitiveness, to an extent, represents their wishes to “level the playing field” and mitigate racial disparities in criminal justice contacts and outcomes (e.g., Brooks & Jeon-Slaughter, 2001; Brunson, 2007; Hagan et al., 2018; Henderson et al., 1997; Horowitz et al., 2019; Hurwitz & Peffley, 2005; Johnson, 2008). As African-American communities have felt the largest effects of mass incarceration, with the imprisonment rate of Black Americans currently at over five times higher than that of White Americans (Guerino et al., 2011), it would be unsurprising if such attitudes may be related to increased support for the use of “second chance” mechanisms as well.

Interestingly, most demographic and background factors, including religion, education, geography, political participation, types of victimization, or Traditional Punishment Orientation scores, showed no or singularly weak predictive effects on support for “second chance” mechanisms. Many of these factors have been related to increased punitiveness in previous work (Payne et al., 2004). Further, although political party and political ideology have been robustly associated with both criminal justice policy attitudes and support for punitiveness in previous work (Langworthy & Whitehead, 1986; Payne et al., 2004; Sims & Johnston, 2004), political party did not predict support for any “second chance” mechanisms and political ideology only weakly predicted support for commutation. Yet, these results do complement recent public opinion data (Barry et al., 2020), further suggesting a degree of bipartisan support, spanning ideological lines, for providing “second chances” to offenders serving long-term prison sentences. Finally, as higher scores on the Rehabilitative Punishment Philosophy Scale predicted higher support for all eight “second chance” mechanisms in this study, this appears to suggest that participants who view rehabilitative and restorative punishments as keys to crime reduction are also significantly more likely to support “second chance” mechanisms across the board. This would not be surprising, as it would be feasible that participants who endorse rehabilitative strategies for crime control, rather than through more traditional modes, also would be more supportive of ways to relieve or reduce incarceration because of its perceived lack of utility for crime reduction.

Second, as existing evidence indicates the public’s general support for giving offenders “second chances” but has not yet examined if and how support may extend to or differ for those convicted of different offenses, this study provides data to suggest moderate, stable levels of public support for the early release of offenders extend to those convicted of both violent and non-violent offenses. Similar levels of support for all eight “second chance” mechanisms were observed for all violent offenses (murder, aggravated assault, robbery) and two of the tested non-violent offenses (serious burglary, non-violent weapon offenses), as compared to general support for such mechanisms. These results indicate that the public supports a wide range of strategies and methods that give “second chances” to offenders incarcerated for violent offenses, including those convicted of murder, at similar levels to the public’s general levels of support for such “second chance” mechanisms.

Although literature suggests that the public may feel differently about considering the early release of those convicted of violent offenses (Applegate et al., 1996; Austin, 1986; Petersilia, 2001), this study does not support such previous work. Although greater levels of public support for harsher punishment for violent offenses is one of the more robust findings in the field of public attitudes toward sentencing and imprisonment (O’Hear & Wheelock, 2019), some recent research may help to explain why participants in this study did not show greater punitiveness toward violent offenses. Fondacaro and O'Toole (2015) found that providing statistical, accurate information about recidivism and incarceration trends tends to reduce punitiveness toward violent offenses; results suggested that framing punishment around this information creates “top-down, rational processing” of punishment, rather than more emotional processing of punishment that respond more to harm, severity, and victimization. As the stimuli in this study also provided recidivism and incarceration data on types of violent offending, this may have led participants to more rationally appreciate a full, complete picture of violent offending and how it should be punished, rather than emotionally reacting to the type or nature of the offense.

Although moderate levels of support were observed for both violent and non-violent offenses, data did show significantly more public support for the use of four “second chance” mechanisms (elimination of parole revocations for technical violations, “second look” sentencing, granting of good time, retroactive application of sentence reduction reforms) for offenders serving long-term sentences for the trafficking of serious drugs. Recent public opinion data have suggested that the public may particularly favor the early release for offenders convicted of particular non-violent offenses, including drug crimes (Pew Charitable Trusts, 2014; Public Opinion Strategies and The Mellman Group, 2012; Sundt et al., 2015; Thielo et al., 2016), and this study provides further evidence.

These results are unsurprising, as both public and policy views toward the punishment of drug crimes have shifted in recent years, leading to political and legal reevaluation of the utility of long-term incarceration as a strategy to fight the “War on Drugs” (Berryessa, 2021; Pfaff, 2017). In fact, each of the four “second chance” mechanisms mentioned above is actually currently available in several jurisdictions for types of drug felonies (Mauer, 2018). For example, the 2010 Sentencing Reform Act in South Carolina included changes and increases in administrative sanctions as responses for technical violations to a variety of drug and non-violent felonies as alternatives to reincarceration (South Carolina S.B. 1154, 2009). A recent Nebraska statute allows those convicted of certain drug felonies to gain good time credits even before serving a mandatory minimum sentence (Nebraska Revised Statutes § 28-105, 2019). The Second Look Act of 2019, which provides for federal judicial resentencing of sentences longer than 10 years, particularly encourages the use of “second look” sentencing for those convicted of drug trafficking because of the burden they represent as nearly half of all federal prisoners (Connor, 2019). Further, many states have enacted retroactive sentencing reforms, such as doing away with mandatory minimums or “three strikes” laws, to those with different felony drug convictions (Wool & Stemen, 2004).

It is interesting to note, however, that none of the four mechanisms mentioned above are strategies, as described by the Prison Policy Initiative, that involve parole boards or governors; instead, these mechanisms make it easier for offenders to be released from prison early via legislation or credits without the help of parole, allow sentences to be reconsidered by judges, and make it more difficult for already released offenders to return to prison (Renaud, 2018). This may suggest particular public interest in utilizing certain “second chance” mechanisms for offenders convicted of the trafficking of serious drugs that do not put the power of early release in the hands of parole boards and/or governors. Future work should explore if and why the public may exhibit some degree of apprehensiveness toward parole boards and/or governors as those making these decisions.

Third, at least of the factors known to be important to the public’s general support for “second chances” (Barry et al., 2020), this study indicates that the immense cost of incarceration to taxpayers may motivate the public’s increased interest in using the four “second chance” mechanisms mentioned above for offenders convicted of the trafficking of serious drugs. Increased participant support for the use of elimination of parole revocations for technical violations, granting of good time, retroactive application of sentence reduction reforms, and “second look” sentencing for offenders incarcerated for the trafficking of serious drugs were all individually and fully mediated by the importance of cost and wasting tax payer dollars on offenders original sentences.

Over $250 billion of US taxpayer money is spent on incarceration per year (Henrichson & Delaney, 2012), but data suggest that public interest in using that money for incarceration, as compared to using it for community-based corrections or sentencing alternatives, is actually relatively low (Cohen et al., 2006). Indeed, research has suggested that the public’s punitiveness may indeed be responsive to the cost salience of incarceration as taxpayers and motivate reduced support for punishment. Several studies have found that providing information about the salience of cost reduces the public’s recommendations for the use and length of incarceration (Aharoni et al., 2019; Aharoni, Kleider-Offutt, & Brosnan, 2020a; Gottlieb, 2017; Thomson & Ragona, 1987). One study even found that cost salience significantly reduced public interest in long-term incarceration, but information on public safety benefits of reduced incarceration had no effect (Aharoni, Kleider-Offutt, Brosnan, & Fernandes, 2020b). Interestingly, this study similarly found that the importance of cost, but not the notion of offenders no longer representing a threat to public safety, motivated participants’ increased support for the use of “second chances” for offenders convicted of trafficking of serious drugs.

Yet, why might cost motivate increased interest in using “second chances” for those convicted of the trafficking of serious drugs? Literature suggests that two perspectives on how cost salience may affect attitudes toward incarceration could be relevant to the current study. The deontological perspective suggests that the criminal justice system has a categorical duty to punish offenders for violations of moral values; the cost of incarceration should be less relevant to support for long-term sentences because the desire for retribution and “righting a moral wrong” overrides interest in its cost (Aharoni & Fridlund, 2012; Berns et al., 2012; Tetlock, 2003). Conversely, the rational choice perspective suggests that the public’s support for incarceration should be related to self-interest as those whose taxes pay billions of dollars per year towards incarceration and show equal consideration of all relevant costs and benefits of incarceration; the public’s interest in saving taxpayer money (the costs) should outweigh retributivism or the desire to punish (the benefits), motivating less support for incarceration and long-term prison sentences that “break the bank” (Aharoni, Kleider-Offutt, & Brosnan, 2020a; Starmer, 2000).

From these perspectives, it is possible that the public may be less likely to view the trafficking of serious drugs as a crime resulting in a violation of moral values, and therefore, their interest in seeking retribution and “righting a moral wrong” does not supersede their interest in the cost of incarceration. Indeed, evidence indicates that cost salience’s ability to reduce the public’s recommendations for the use and length of incarceration may be most effective in relation to crimes perceived to be less serious moral violations (Aharoni et al., 2019; Aharoni, Kleider-Offutt, & Brosnan, 2020a; Gottlieb, 2017; Thomson & Ragona, 1987). It is true that views of drug crimes have begun to change in the last two decades. The rise of the incredible punitiveness of the public toward drugs through the turn of the 21st century was thought to be due to “moral panic,” with the US public and policymakers viewing drugs as a “folk devil” that represented a moral attack on the country; for decades, many members of the public believed that drug offenses were a, if not the, main contributor to violent crime rates (Mizell & Siegel, 2014; Vitiello, 2020). Yet, Hart (2002) argues that, in the eyes of the public, the “War on Drugs” arguably failed and was viewed as largely fruitless in affecting crime.

Instead, more recent data demonstrate the majority of the public no longer believes that drugs are the pressing issue they once were and that the seriousness of drug offenses does not necessarily warrant the harsh, long-term prison sentences, particularly coming from mandatory minimums or three strikes laws, still currently used in many jurisdictions (Doherty et al., 2014; Lake et al., 2013). Thus, this literature indicates that the public’s more recent feelings toward drug-related offenses and incarceration could potentially allow for their equal consideration of the relevant costs and benefits of the incarceration for those convicted of trafficking of serious drugs; in the case of this study’s results, this may suggest participants’ ultimate deferral to their interest in cost and saving taxpayer money as the priority when thinking about long-term prison sentences for these offenders, potentially leading to support for “second chance” mechanisms that can achieve cost saving benefits by providing early release.

It is important to note that, although sentiments toward the long-term incarceration of drug crimes have indeed shifted in recent years (Berryessa, 2021; Pfaff, 2017), recent poll data have shown that sentiments toward the use of long-term incarceration for violent and other non-violent offenses have also changed (ACLU, 2017). Many members of the public now question the use of long-term incarceration for both violent and non-violent offenses, with the ACLU (2017) even finding 61% of voters believing that violent offenders can turn their lives around if released. Yet, besides trafficking for serious drugs, the current pattern of significant results discussed above, along with the mediation results, was not observed for other types of offenses.

One possible reason for this may be that attitudes toward the use of “second chance” mechanisms for other offense types, including other non-violent offenses, may be influenced by competing values or factors. Indeed, Brewer and Gross (2005) argue that members of the public often consider support for policies in terms of their values; “when they think about a policy choice, they base their opinions on the connections that they draw between the issue and their core beliefs” (p. 930). In many instances, “core beliefs” or values compete to influence support for policies (Brewer & Gross, 2005). The current study may suggest that members of the public consider support for “second chance” mechanisms for the trafficking of serious drugs in terms of cost, as their predominant “core belief,” while other values may compete to influence the public’s levels of support for such mechanisms for other types of offenses. This could potentially lead to countervailing “core beliefs” that pull the public’s support for “second chance” mechanisms in different directions based on different values (Brewer & Gross, 2005), potentially resulting in overall null results for other offense types. Ultimately, future work should examine why increased support for these specific “second chance” mechanisms did not extend to other types of offenses and the potential role of countervailing “competing values” in influencing public support.

Before discussing implications of this work, there are some limitations to note. Randomized experimental survey methods allow for isolating effects of variables on public attitudes, and they reduce effects of social desirability (Auspurg & Hinz, 2014). However, data in this study used outcome measures of support on interval scales, rather than binary measures of support often used in polls (“yes”/“no”). The current data do and should not replace opinion polls in order to gauge public attitudes on these issues, and lines of inquiry examined in this study should both be replicated with similar and other experimental materials, as well as surveyed using larger-scale public opinion polls via both the internet and telephone. Further, it is also possible that current events surrounding data collection could have affected participants’ views on the current issues (i.e., COVID-19 pandemic, George Floyd protests). Future work should use larger general public samples, as well as other sampling sources, systems, and methods, as this sample was limited to individuals who opt-in to Qualtrics Panel. Particularly, future work should poll a representative sample of US voters on these issues, as well use probability samples. Although this work is a worthy first step, much more data on these issues are needed in order to move forward with actionable policy recommendations.

This work also only examined a limited number of “second chance” mechanisms and types of offenses, and the public’s views on an expanded list of mechanisms and offense types should be examined as well. Further, the public’s support for “second chance” mechanisms are likely motivated by other factors besides those discussed by Data for Progress, in Barry et al. (2020) and used in this study, and additional factors should be examined as mediators. Finally, this study did not explore how randomizing other factors, such as criminal background, race, and/or socioeconomic status of offenders, along with offense type might influence public support for offenders’ “second chances” from long-term sentences. Particularly, as minority communities are disproportionately affected by incarceration and its collateral consequences in the USA (Austin et al., 2016), future work should examine how the current results may extend to more complex experiments looking at race and “second chance” mechanisms.

One other final potential limitation of this work is the use of the Call and Gordon (2016) punishment orientation scales. Previous work has used these scales to control for participants’ general punishment orientations related to traditional and rehabilitative punishments (e.g., Call, 2018; Richards, 2020; Sparks, 2021), and they were chosen for the current study because they encapsulate participants’ orientations toward five goals of punishment in the US justice system (retribution, incapacitation, restoration, rehabilitation, deterrence) (Call & Gordon, 2016). However, the inclusion of these measures as controls in the current models, due to the structure of the scales themselves, did not control for participants’ orientations toward two established punishment philosophies that are often directly compared: utilitarianism and retributivism (see Frase, 2005). For example, both punishment scales in this research asked participants to indicate support for several different methods of reducing crime (e.g., eye-for-an-eye, keep criminals off streets), but the goal of crime reduction, itself, can be considered a utilitarian goal of punishment (Frase, 2005). Therefore, support for certain punishment goals that may have nothing to do with crime reduction, such as retributivism or even restoration, might not be appropriately measured by these scales or composite measures. As such, these results likely do not control for participants’ orientations toward utilitarian or retributive philosophies of punishment. Future work on these issues, as well replications of the current study, should use well-established scales that measure support for utilitarian and retributive punishment philosophies in order to control for these two punishment philosophies, as well as to see if and how each philosophy may predict support for different “second chance” mechanisms.

Ultimately, this paper provides implications for policy and incarceration in the USA. Truly addressing the USA’s reliance on mass incarceration, as well as ensuring that our sentencing policies encourage public safety, fiscal accountability, and justice, requires the active reconsideration of those who are already long-term incarcerated and options for their meaningful release (Clear & Austin, 2009; Fair and Justice Prosecution Working Group, 2020; Pfaff, 2017; Renaud, 2018). Although “second chance” mechanisms, as ways to effectively reexamine of and provide early release to those serving long-term prison sentences, appear to be modes of providing such reconsideration, they still remain vastly under implemented and used at all governmental levels because necessary political action of policymakers and leaders has not yet been taken (Barry et al., 2020; Renaud, 2018). In order for our reliance on mass incarceration and its significant negative consequences to our communities to be mitigated, these mechanisms should be considered by politicians and policymakers (Petersilia & Cullen, 2014).

As existing literature suggests that support of the US public for the use of “second chance” mechanisms could help spark action and “political will”, the current work affords such an initial step to demonstrate the latitude of public support on these issues to policymakers. Members of the public appear to be moderately and consistently supportive in providing offenders “second chances” using the most commonly available mechanisms and strategies found at all governmental levels. Such levels of public support not only appear to apply to general support for the use of these mechanisms, but also apply to public support for their use in reconsidering the sentences and early release of offenders convicted of a range of both violent and non-violent offenses, and particularly, for those convicted of the trafficking of serious drugs. Although levels of support for “second chances” may vary by particular demographics including age, gender, and race, they do appear to span across many demographics, geography and, most interestingly, ideological and party lines. Overall, although levels of support may not be overwhelming, members of the public appear open and supportive to utilizing “second chance” mechanisms in a variety of contexts, with levels of support showing no opposition to the use of any of the tested “second chance” mechanisms, either generally or for any specific offense.

Such attitudinal trends regarding the use of “second chance” mechanisms in response to long-term prison sentences, indicating relatively consistent, bipartisan support and salience of the current issues to members of the public, provide an invitation to politicians and policymakers to “follow the lead” of the public sentiment and at least begin to explore the potential use and expanding the use of such mechanisms in their jurisdictions (Canes-Wrone et al., 2014; Enns, 2016; Erikson et al., 2002; Jennings et al., 2017; Stimson, 2004). As available mechanisms and their eligibility to offenders vary widely based on the jurisdiction (Renaud, 2018), stable support seen for the eight most commonly available “second chance” mechanisms suggests that if politicians and policymakers were interested in utilizing or even expanding the use of mechanisms, it is likely that one or more of these eight strategies may already be available or eligible for offenders in their jurisdictions. Further, as political and policy leaders continue to search for ways to reduce our reliance on mass incarceration, it is important to note that individuals convicted of the offenses examined in this study in sum make up almost 60% the current total US prison population (Austin et al., 2016). This suggests that considering the use of “second chance” mechanisms for individuals convicted of these offenses can and would have an enormously meaningful effect on incarceration in the USA, as well as its human and economic impact, and could be a key step in moving criminal justice policy in a non-punitive direction (Petersilia & Cullen, 2014).

Further, the current findings both suggest that politicians and policymakers’ first steps in the potential use and expansion of “second chance” mechanisms might begin with exploring how to apply them to or make them eligible for those convicted of trafficking of serious drugs. In the last 10 years, both federal and state legislations have moved toward lessening sentences and reducing prison populations for drug offenses, such as the First Step Act which provides federal prisoners with both prospective and retroactive relief from long-term prison sentences for some federal drug felonies (Desilver, 2014). This suggests a political and policy climate that is now more accepting of “second” chances for those convicted of some drug felonies. This, paired with these results, indicates a certain level of both public and policy interest in providing “second chances” to those convicted of trafficking of serious drugs.