Abstract

Objectives

To experimentally evaluate the effects of personal protective equipment (PPE) on participants’ perceptions of police during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

As part of the experimental paradigm, participants were randomly assigned to read a fictitious news article about the utility of PPE (i.e., pro-PPE, anti-PPE, or neutral), and then rate images of a police officer using different items of PPE (i.e., masks, goggles, face shields, and/or medical gloves) along eight dimensions.

Results

The analyses reveal that participants overwhelmingly perceived the use of PPE as both important and beneficial, regardless of condition. The analyses also reveal that the use of PPE impacted perceptions of the pictured officer, but that the specific perceptual effects of such PPE varied by the item used.

Conclusions

Police worldwide have attempted to reduce the risks associated with COVID-19 by using PPE. In addition to functional benefits, many items of PPE also present perceptual benefits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The outbreak of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) has had a tremendous impact on society worldwide. Following the World Health Organization’s (WHO) declaration of the virus as a pandemic in March 2020, federal, provincial, and state governments across the world have implemented considerable stay at home and social distancing orders in hopes of reducing the spread of the virus. Although these orders have been applied to much of the general population, the adherence to these orders has not been possible by all people. For example, police officers as essential service providers have been forced to remain on duty during the pandemic. The inability for police to stay home and/or socially distance has presented significant challenges for those working the frontlines of policing operations. Given that COVID-19 spreads rapidly from direct, indirect, and/or close contact with infected persons (many of whom may be asymptomatic) as well as by contact with contaminated surfaces (WHO 2020a, b), the nature of police work inevitably subjects its officers to environments which increase their risk of exposure to the virus.

Recognizing the harsh realities of the pandemic, many police officers have begun using personal protective equipment (PPE), including gloves, face masks, face shields and eye protection, as part of their routine practices. However, while PPE has been shown to be effective at inhibiting viral spread (Chu et al. 2020; Cook 2020; Thomas et al. 2020; WHO 2020a, b), past literature has empirically demonstrated that many of the items that actually constitute PPE can result in negative public perceptions when used by police (at least in other contexts). In an era of policing where the uniform is such an important piece of police equipment (Bell 1982; Bickman 1974; Durkin and Jeffery 2000; Joseph and Alex 1972; Simpson 2017, 2020a; Singer and Singer 1985), and where changes in police esthetics can impact perceptions of officers (Boyanowsky and Griffiths 1982; Johnson et al. 2015; O’Neill et al. 2018; Pica et al. 2020; Simpson 2017, 2019, 2020a; Yesberg et al. 2020), any sudden alterations to the uniform could impact public perceptions and community relations. The present research thus uses a between-subjects design with within-subjects variation to experimentally test the effects of PPE on perceptions of police in the context of PPE awareness. The analyses reveal that participants overwhelmingly perceived the use of PPE as both important and beneficial, regardless of condition, but that the specific perceptual effects of such PPE varied by the item used. Considering the salience of the change in police esthetics induced by the use of PPE, the present research sheds insight into the consequences of the pandemic for the criminal justice system.

What is COVID-19?

COVID-19 is a highly infectious, contagious, and potentially fatal virus that attacks the respiratory system (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2020; WHO 2020b). As of the present time, there have been more than 1,100,000 confirmed deaths attributed to the virus worldwide (WHO 2020c). Although knowledge on the matter is dynamically evolving, current research suggests that the virus is primarily spread through respiratory droplets and airborne aerosols, which enter the body via the mouth, nose, and/or eyes after direct, indirect, and/or close contact with infected persons or surfaces (WHO 2020a, b). Due to its ease of exposure and the fact that many infected persons may be asymptomatic (WHO 2020b), any public contact poses a risk for transmission of the virus.

Policing during the COVID-19 pandemic

Despite the WHO’s declaration of COVID-19 as a pandemic and the subsequent implementation of stay at home and social distancing orders by various governmental agencies, police have maintained their frontline operations. Although some policy changes have been implemented to accommodate for increased telephone or online responses (e.g., for less serious or non-active events), the nature of policing still often requires in-person attendance at the location of events (e.g., for serious or active events), which places officers in close contact with the public and in circumstances where social distancing may not be possible (e.g., during safety searches). Indeed, much police work involves unavoidable contact with the public, and these kinds of circumstances naturally put officers at greater risk of the virus simply via their attendance. Moreover, in some instances where physical attendance is required, officers’ risk of exposure can be amplified by the deliberate actions of the parties involved in the issues being policed. For example, police have been the target of intentional coughing attacks by individuals claiming to have the virus (Malone 2020). As a result, the necessity of police attendance at events and the potential reception to officers during such attendance can increase their risk of exposure to the virus.

Personal protective equipment

Like other frontline workers who must still engage in public contact during the COVID-19 pandemic, police worldwide have attempted to mitigate the risks of the virus by using PPE. For example, the Vancouver Police Department (2020) has supplied their officers with gloves and personally-outfitted respiratory masks and recommended that they use them whenever applicable. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC 2020) has also recommended that law enforcement personnel use eye protection, including face shields and goggles, to further mitigate the risk of virus exposure. While a budding body of literature has begun to investigate the impact of COVID-19 on other elements of policing (e.g., Ashby 2020; Farrow 2020; Jennings and Perez 2020; Jones 2020; Reicher and Stott 2020; White and Fradella 2020), research has yet to examine how using these different items of PPE may impact perceptions of officers. It is essential that this gap be addressed given the importance of perceptions for contemporary policing: as we argued earlier in this article, people judge police based upon appearance and their appearance has now changed as a result of the pandemic. Different forms of police equipment can signal different kinds of intent (e.g., see Simpson 2019, 2020a), and therefore, it is possible that different items of PPE may exhibit perceptual effects as well. In the subsequent sections, we thus describe some of the common items of PPE used by officers and their implications for both health and safety in order to then situate our hypotheses for the present research.

Gloves

Although the use of gloves by police is not new given their functional benefits (Simpson 2020a), they have become particularly popular during the COVID-19 pandemic. Such popularity is largely due to two reasons. First, gloves protect officers from direct contact with citizens who may be carriers of the virus (WHO 2020d). Second, gloves provide an extra barrier to skin contact against contaminated surfaces (WHO 2020d). While gloves do not replace the importance of proper hand hygiene (WHO 2020e), their usage is beneficial for reducing opportunities for the virus to spread, particularly among officers who may not have immediate access to hand washing or sanitizing stations.

Face masks

Simple behaviors like coughing, sneezing, and talking can produce respiratory droplets and aerosols which can contain the COVID-19 virus (Thomas et al. 2020). Without adequate facial protection, exposure to these behaviors can thus spread the virus. With that being said, face masks have been shown to be effective at inhibiting such spread (Chu et al. 2020; Cook 2020; WHO 2020a, b) and have thus become very popular during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nonetheless, they still vary in both their efficacy and style (e.g., surgical masks versus N95 masks versus full-face respirator masks): although surgical masks provide benefits, more advanced respirator-style masks have been shown to provide superior coverage (Chu et al. 2020).

Eye protection and face shields

While it appears that eye protection and face shields have not been used by police during the COVID-19 pandemic to the same extent as gloves and face masks, they both have been shown to reduce hand-eye contact, which is another vehicle by which the virus can spread (Chu et al. 2020; Mukamul 2020; Thomas et al. 2020). For this reason, the CDC (2020) has recommended that law enforcement personnel use these equipment whenever possible. Similar to gloves, however, eye protection and face shields do not provide adequate protection if used exclusively on their own (Lindsley et al. 2014; Roberge 2016; Thomas et al. 2020). Instead, these items of PPE are most effective when used in combination with other items of PPE (French et al. 2016), like those discussed in the preceding sections.

The importance of police appearance and the PPE paradox

Historically, PPE has not been used as part of routine police operations. Nonetheless, it has become very popular during the COVID-19 pandemic given its aforementioned health and safety benefits. It remains unknown, however, how an officer’s routine use of PPE may be perceived by the public. Theoretically, when accounting for the literature surrounding COVID-19, police officers who use PPE should be perceived favorably, seeing that by using PPE, they demonstrate a cognizant awareness of the growing body of medical recommendations regarding the handling of the virus (e.g., Chu et al. 2020; Cook 2020; Thomas et al. 2020; WHO 2020a, b). Moreover, by using PPE, officers may reaffirm their status as role models within their respective communities by visibly following health guidelines and demonstrating the same types of pro-social behavior that they expect of the public.Footnote 1 In this idealistic scenario, PPE should not pose a perceptual problem for police: officers should be perceived more favorably when using PPE than when not using PPE. However, the logic of this model may not be so simple.

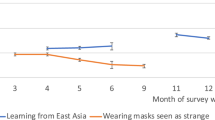

One element that may moderate the perceptual effects of PPE regards awareness. Over the course of the pandemic, conflicting opinions have emerged in both media and public rhetoric about COVID-19 and its management (e.g., see Carlson 2020; Darcy 2020; Hughes et al. 2020; National Post 2020). While many media outlets have highlighted the dangers associated with the virus and advocated for the use of PPE on the backing of best medical practices, other media outlets have gone as far as to undermine the severity of the virus, at times even suggesting the pandemic to be a disguise for an underlying political agenda (e.g., see Halon 2020).

While this mixed-message rhetoric regarding COVID-19 may not always be explicitly about PPE, public perceptions about the importance of PPE may be derived from beliefs about the severity of the pandemic itself: in order to perceive the use of PPE as beneficial during the pandemic, one must first believe that PPE can be used to mitigate the risks of the virus. In this way, beliefs about the utility of PPE may be inextricably linked to beliefs about the relevance of PPE in a specified context. For example, some people may argue that PPE might not be helpful for preventing the spread of COVID-19 if they question the virus itself, but those same people may still believe that PPE could be effective in other contexts, such as in a hospital’s operating room (which would suggest that they still believe PPE itself has benefits, just not in the COVID-19 context). Thus, although police are using PPE right now for a justifiable purpose (i.e., to protect against COVID-19), a lack of understanding and/or appreciation by the public about such purpose could potentially result in the use of PPE being perceived by the public through a more negative lens.

The plausibility of this latter prediction is magnified by the irony that the very items that often constitute PPE have traditionally been associated with negative perceptions of police. For example, Simpson (2020a) found that black gloves exhibited negative effects on citizens’ perceptions of officers, perhaps because the presence of gloves suggests an anticipation of unwanted physical contact. While little to no empirical literature has specifically examined the perceptual effects of face masks on police, existing research and current rhetoric suggest that they too may have important perceptual implications. For example, face masks can hinder communication and inhibit the display of facial expressions which may contribute to more dehumanized interactions between the public and the police (Simpson 2020b). Moreover, specific types of face masks (e.g., full-face respirator masks) may elicit perceptions associated with hostile and/or militant behavior given that similar masks have traditionally been used by police as part of their tactical riot gear during public disorder situations where tear gas and/or other chemical agents are deployed (Kraska 2007; Lawson 2019). And the same logic applies to face shields: officers who employ face shields have traditionally been associated with riot squads and SWAT teams which are often perceived as being militarized (Kraska 2007; Lawson 2019). Face shields may therefore elicit negative perceptions associated with aggressive intentions and/or hostile situations as well. Finally, eye protection (including sunglasses) poses a similar paradox: while sunglasses may provide a supplementary shield from hand-eye contact and respiratory droplets, they too have been shown to induce negative perceptions of police (Boyanowsky and Griffiths 1982; Simpson 2020a).

Overview of the present research

While the importance of PPE during the COVID-19 pandemic has been well documented, less attention has been paid to how police officers who use the equipment may be perceived. In fact, the use of PPE to try and help combat the spread of the virus may have actually created a conundrum for police, whereby the implications of using the equipment for health and safety may come at the risk of negative public perceptions. Given that the uniform is such an important symbol of police legitimacy and can impact perceptions of police, the addition of PPE and/or any other accoutrements which impact the esthetics of the uniform may affect citizens’ perceptions of officers. The present research thus explores how police who use PPE are perceived by the public. Using a between-subjects design with within-subjects variation, we experimentally test the effects of PPE on perceptions of police in the context of PPE awareness. With regard to awareness, we propose the following hypotheses:

-

Hypothesis #1: Participants who are made immediately aware of the health benefits of PPE will be more likely to perceive police using PPE favorably than participants who are not made immediately aware of the health benefits of PPE or informed that PPE does not present health benefits.

-

Hypothesis #2: Participants who are made immediately aware of the lack of health benefits of PPE will be more likely to perceive police using PPE negatively than participants who are not made immediately aware of the lack of health benefits of PPE or informed that PPE presents health benefits.

With regard to specific items of PPE, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis #3: Participants will perceive police less favorably when they are using items of PPE that have traditionally been associated with militarization (e.g., full-face respirator masks, face shields) than when they are using items of PPE that have traditionally been associated with medical practices (e.g., surgical masks, N95 masks, goggles, medical gloves).

Data and methods

Participants

We recruited 270 participants via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (herein after referred to as “MTurk”) for the present research. MTurk is a popular sampling platform which allows researchers to use crowdsourcing to collect remote data from participants in return for compensation. Previous research has found this platform to provide diverse and representative samples quickly, conveniently, and at low costs (Buhrmester et al. 2011; Casler et al. 2013; Mellis and Bickel 2020; Mortensen and Hughes 2018; Paolacci et al. 2010; Simpson 2020b). All participants recruited for the study were (1) registered on MTurk, (2) residing in North America, (3) at least 18 years of age, and (4) able to speak, read, and write English.

All participants who enrolled in the study were randomly assigned to one of three different conditions: pro-PPE, anti-PPE, or neutral. As outlined below, participants in each condition read a fictitious news article that strategically manipulated awareness about the health benefits, or lack thereof, of PPE. A manipulation check question was then used to assess if participants internalized the messaging of their assigned article.Footnote 2 Participants who failed this question were excluded from our analyses given that we could not confirm delivery of our treatment as intended (see below).

The final sample of 117 participants who passed the manipulation check question and were therefore retained for our analyses included 48 women and 69 men. Participants ranged in age from 21 to 77 (M = 39) and self-identified as Asian (7), Black (15), White (81), and mixed (2) or unknown (12) race. Most participants identified as being married (68) and reported having a Bachelor’s degree (66). Most participants also reported that their income was about average (67) compared to other people living in the country (see Table 1 for the full descriptive statistics).

Procedure

Using a between-subjects design with within-subjects variation, we experimentally tested the effects of PPE on perceptions of police in the context of PPE awareness.Footnote 3 Upon enrollment in the study, participants were advised that the study sought to investigate public attitudes about the use of PPE during the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants were further informed that they would: (1) be assigned to read a newspaper article discussing COVID-19 and answer questions about the content of such article, (2) rate images of people using PPE on a number of different variables, and then (3) complete a series of questions about themselves and their thoughts. The use of the generic term “people” in lieu of the specific term “police” was necessary to minimize potential demand characteristics that could have otherwise biased participants’ perceptions of police. Following completion of the task, participants were provided with a debriefing information sheet that contained information about the study and contact information for the research team. The study was conducted entirely online and required approximately 20 min to complete.

News articles

As part of the experimental paradigm, participants were randomly assigned to read one of three different news articles from a fictitious newspaper: The Morning Gazette. Although all three articles shared the same “root text” in the first half of the article (which introduced COVID-19 and its infectious nature), they varied in their “manipulation text” in the second half of the article. In the pro-PPE article, the manipulation text discussed the health benefits of PPE. In the anti-PPE article, the manipulation text discussed the lack of health benefits of PPE. In the neutral (or “control”) article, the manipulation text continued the generic discussion of COVID-19 with no mention of PPE.

All three articles were modeled after real news reports. In order to ensure internal validity, all facets of the articles aside from the aforementioned manipulation remained the same across articles. For example, the word count of all three articles was identical. All three articles also included comments from both a fictitious Chief Medical Officer and a fictitious Mayor. None of the articles referenced any specific geographic locations in their text or titles to minimize the risk of associating the content of the article with any specific geographic location. None of the articles referenced police: they were designed to be intentionally generic and not specific to any occupation or context.

As mentioned above, participants who incorrectly answered the manipulation check question about the messaging of their assigned article were excluded from our analyses given that we could not confirm delivery of our treatment as intended. For example, if a participant assigned to the anti-PPE condition responded to the associated question by stating that the article suggested that PPE was beneficial, we were not confident that they accurately internalized the messaging of their assigned article. This resulted in the exclusion of approximately 20% of participants in the pro-PPE condition (final n = 47), 60% of participants in the anti-PPE condition (final n = 40), and 70% of participants in the neutral condition (final n = 30). We theorize potential explanations for the high failure rates among the anti-PPE and neutral conditions in our “Results” and “Discussion” sections.

Perception task

After reading their randomly assigned news article and answering the associated question, participants completed the perception task. As part of such task, participants rated 12 different images of a uniformedFootnote 4 White male officer using different items of PPE on eight dependent variables (as described below). In the first six images, the officer used one of the following items of PPE: (1) a surgical mask, (2) an N95 mask, (3) a full-face respirator mask, (4) goggles, (5) a face shield, or (6) single-use medical gloves (light blue in color). In the subsequent five images, the officer used a combination of the aforementioned items of PPE, including: (7) medical gloves and a surgical mask, (8) medical gloves and an N95 mask, (9) medical gloves and a full-face respirator mask, (10) medical gloves, an N95 mask, and goggles, or (11) medical gloves, an N95 mask, goggles, and a face shield. In the twelfth (control) image, the officer did not use any PPE. These specific images were selected to not only isolate individual items of PPE, but also to examine the perceptual effects of popular combinations of PPE used by officers.

In order to ensure the realism of both the officer and the PPE used by the officer, all images were collected with the assistance of a local police department. All names and other identifiers of the officer were digitally removed for the purposes of the present research. Removing such elements ensured that the uniform appeared as generic as possible: the dark blue uniform worn by the officer in the experiment appears almost identical to the dark blue uniform worn by most police agencies across North America. All elements of the images with the exception of the PPE being manipulated were held constant across the images (e.g., same [neutral] facial expression, posture).

All images of the officer were taken in a public environment where members of the public (i.e., staged volunteers) were present but not focal. Including members of the public in the images was necessary to make the use of PPE meaningful (i.e., one could argue that using PPE is potentially irrelevant in the absence of other people). All members of the public were situated in the same position across the images and their faces were always blurred to emphasize the focus on the pictured officer. The order of the presentation of images was randomized across participants to control for potential order effects.

Dependent variables

We measured participants’ perceptions of the pictured officer in each esthetic capacity via eight questions that tapped into eight different dimensions: accountability, aggression, approachability, competency, friendliness, intimidation, professionalism, and respectfulness. As part of each question, we asked participants to indicate their level of agreement with each listed dimension (“This officer is [DEPENDENT VARIABLE]”) using a 5-point Likert scale (which ranged from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”). In order to reduce selection and response biases, the order by which participants rated the officer along these eight dimensions randomly varied across participants.

Analytic strategy

We employ a series of inferential analyses to tease apart the effects of our awareness manipulations on perceptions across conditions as well as our PPE manipulations on perceptions within conditions. As part of the former, we test for differences in perceptions of the officer using PPE (i.e., average rating for all eleven PPE images) across conditions using ANOVA tests (i.e., between-subjects). As part of the latter, we test for differences in perceptions of the officer by PPE within conditions using t tests (i.e., within-subjects). Within these particular analyses, the officer acts as their own analytic control: ratings of each image of the officer using PPE are compared against ratings of the same officer not using PPE (i.e., control image). Tests for each dependent variable are conducted individually. All tests are assessed against the p < 0.05 standard.

Results

Effects of PPE awareness

In order to test our first two hypotheses regarding the effects of awareness of the health benefits, or lack thereof, of PPE on perceptions of police using PPE, we begin by employing ANOVA tests to assess differences across our three conditions (i.e., pro-PPE, anti-PPE, and neutral) for each of our eight dependent variables. As shown in Table 2, the ANOVA tests only revealed significant variation across conditions for the dependent variable of aggression (F(2, 114) = 3.953, p < 0.05). Follow-up pairwise comparisons using the Bonferroni correction indicated that this difference was the result of variation between the pro-PPE and anti-PPE conditions: participants in the pro-PPE condition perceived the officer to be significantly more aggressive than participants in the anti-PPE condition. We did not observe any other significant differences in the results of the ANOVA tests.

We theorize that the absence of significant differences among the ANOVA tests may be a function of two mechanisms. First, and from a methodological perspective, it is possible that our sample size hindered our ability to detect statistically significant effects. Second, and from a more substantive perspective, it is possible that in the absence of any other information, participants in the neutral condition simply applied their pre-existing beliefs about the benefits of PPE to their ratings of the images (and a similar logic may apply for the anti-PPE condition as well). Indeed, the means for most dependent variables for the neutral condition were either very similar to the pro-PPE condition or somewhere in-between the anti-PPE and pro-PPE conditions (which reduced the total variation across groups). This logic regarding the application of pre-existing beliefs is further substantiated by two related observations. First, 80% of participants in the neutral condition agreed or strongly agreed that the police should use PPE whenever possible during the COVID-19 pandemic when queried as part of a concluding survey. Second, more than 90% of participants in the neutral condition who inaccurately answered the manipulation check question selected the response that PPE is very helpful for preventing the spread of the virus.

In light of these caveats, it is worth noting that the results still generally trended in the directions consistent with our hypotheses: across our dependent variables, participants in the pro-PPE condition generally perceived the officer more favorably than participants in the anti-PPE condition. If the sample size is thus driving the absence of observed significance among the ANOVA tests, these trends become meaningful. And, indeed, if we relax the threshold for significance to a standard of p < 0.10, the ANOVA test for the dependent variable of approachability becomes significant and the ANOVA test for the dependent variable of accountability approaches significance, both in the hypothesized directions.

Effects of specific items of PPE

In order to test for perceptual differences among specific items of PPE, and particularly, our third hypothesis that more militarized PPE may induce negative perceptions, we next turn to a series of t tests (shown in Table 3). Using the image of the officer without PPE as the control image, we assess differences in ratings for each of the eleven PPE images described in our “Data and methods” section. Note that we only explore within-subjects differences for the pro-PPE (n = 47) and anti-PPE (n = 40) conditions given that (1) there was no mention of PPE in the neutral condition’s news article, (2) so few participants in the neutral condition accurately answered their manipulation check question, and (3) there were no significant differences between their aggregate ratings of the officer and the pro-PPE or anti-PPE conditions’ aggregate ratings of such officer.

Masks

Masks are perceptually salient items of PPE. Their presence on an officer’s face makes them a prominent feature of an observer’s visual field. Relative to no mask, using a surgical mask enhanced perceptions of accountability, professionalism, and respectfulness, regardless of condition. Using a surgical mask also enhanced perceptions of approachability for participants in the pro-PPE condition and perceptions of competency for participants in the anti-PPE condition.

A similar pattern emerged for the N95 mask: using an N95 mask enhanced perceptions of accountability, competency, and professionalism, regardless of condition. Using an N95 mask also enhanced perceptions of respectfulness for participants in the anti-PPE condition.

A different pattern emerged for the full-face respirator mask. Using a full-face respirator mask enhanced perceptions of accountability and professionalism, regardless of condition. For participants in the anti-PPE condition, a full-face respirator mask also enhanced perceptions of competency. However, participants in both conditions perceived the officer using a full-face respirator mask as more intimidating. For participants in the anti-PPE condition, using a full-face respirator mask also amplified perceptions of aggression and reduced perceptions of approachability and friendliness. The full-face respirator mask thus exhibited a mixed effect: although its use translated into more favorable perceptions along some dimensions, it also translated into many negative outcomes along other dimensions.

Goggles

Unlike masks, goggles are not perceptually salient items of PPE. Their clear frame and transparent lens often make them very difficult to observe on a person unless in close proximity to that person. Consistent with this logic, we found no significant differences in perceptions of the officer when using goggles for any of the dependent variables.

Face shields

Similar to goggles, face shields present transparent boundaries between the face of the using party and surrounding persons. Unlike goggles, however, face shields are larger and more visually salient. And, indeed, the presence of a face shield elicited more variation in perceptions of the pictured officer: using a face shield enhanced perceptions of accountability and professionalism, regardless of condition. For participants in the anti-PPE condition, using a face shield also enhanced perceptions of competency, friendliness, and respectfulness.

Medical gloves

Medical gloves are a very popular item of PPE used by police. Using them alone, however, only exhibited perceptual effects for participants in the anti-PPE condition: they enhanced perceptions of accountability, competency, professionalism, and respectfulness.

Combinations of PPE

Lastly, we turn to the results regarding the use of combinations of PPE. Many of the results for these images are similar and so we discuss them together. For example, using medical gloves and any form of mask generally enhanced perceptions of accountability, competency, professionalism, and respectfulness. With that being said, the combination of medical gloves and a full-face respirator mask also amplified perceptions of aggression and intimidation for participants in both conditions, and reduced perceptions of friendliness for participants in the anti-PPE condition. The full-face respirator mask thereby again emerged as potentially problematic in the context of public perception.

When goggles or goggles and a face shield were added to the combination of medical gloves and an N95 mask, a similar pattern emerged as without such items. Given these findings, it would appear that the effect of PPE is not completely additive: once salient items of PPE are already visible on the officer, the presence of additional items exhibits a rather negligible impact on overall perceptions of that officer.

Summary

We observe more variation among the effects of different items of PPE (i.e., within-subjects) than we do for awareness about the utility of PPE (i.e., between-subjects). Consistent with the pairwise comparisons presented in our preceding section, we find that participants in the pro-PPE condition consistently produced higher mean ratings for most items of PPE than participants in the anti-PPE condition. Although it may be tempting to use these results from the t tests to then statistically infer that the pro-PPE condition perceived the officer more favorably than the anti-PPE condition, we recognize that testing this between-subjects question was not the goal of these within-subjects tests, and therefore, using such tests for this purpose arguably inflates the risk of a test error.

Discussion

Despite governmental orders to stay home and socially distance, police have maintained their frontline services during the COVID-19 pandemic. In doing so, officers have continued to engage in close contact with members of the public who potentially could be carriers of the virus. Ensuring the safety and well-being of these officers and preventing further spread of the virus have thus remained goals for both the law enforcement and public health communities. The consequences of an infected police agency are high: not only could it leave communities without first responders, but as a function of their role, it could also mean the widespread infection of many people. Given that police penetrate the networks of so many people (e.g., via their attendance at different homes, workplaces, and public spaces), one infected officer could infect many different social groups during the course of any shift.

In an effort to reduce the risks of the virus, police among others worldwide have adopted the use of PPE, which has been identified as providing many health and safety benefits (e.g., Chu et al. 2020; Cook 2020; Thomas et al. 2020; WHO 2020a, b). The implications for the use of PPE, though, are not necessarily consistent across all people: the use of PPE could create a conundrum for police, whereby their use of the equipment to protect themselves and others could potentially induce negative perceptions which could then tarnish their ability to effectively conduct their duties. This is largely because several items of PPE that are used by police, including gloves, specific types of face masks, face shields and eye protection, have traditionally been associated with negative messaging in policing (including hostility and militarization; e.g., Boyanowsky and Griffiths 1982; Kraska 2007; Lawson 2019; Simpson 2020a) and/or hinder the display of expressions found to enhance perceptions of police (e.g., Simpson 2020b). Until now, however, no known research has empirically tested these claims and/or the effects of PPE on perceptions of police in a pandemic context. Considering the magnitude of esthetic change that using PPE has induced for police, understanding the effects of PPE on perceptions of police helps to conceptualize the broader impact of this public health crisis on the criminal justice system. As part of the present research, we thus employed an experimental paradigm with multiple levels of randomization to test the perceptual effects of different items of PPE on perceptions of police in the context of PPE awareness.

As introduced at the outset of this article, one potential complication surrounding perception regards awareness. People observe police in different capacities and with different levels of awareness about the rationale for why officers use particular equipment. Although some equipment may exhibit baseline effects in the absence of any contextual information (for discussions, see Simpson 2019, 2020a), other equipment may exhibit different effects depending upon an observer’s belief about the utility of the equipment in a specified context. Testing this effect of awareness in the context of COVID-19 and PPE was a primary goal of the present research. As part of the experimental paradigm, participants were randomly assigned to read a fictitious news article that either highlighted the health benefits of PPE (i.e., pro-PPE condition), the lack of health benefits of PPE (i.e., anti-PPE condition), or never mentioned PPE at all (i.e., neutral condition), and then immediately after rated images of a police officer using the very items of PPE that the article discussed along eight dimensions: accountability, aggression, approachability, competency, friendliness, intimidation, professionalism, and respectfulness.

The results from the ANOVA tests provided limited evidence to suggest that simply reading a fictitious news article about the health benefits, or lack thereof, of PPE could substantially impact perceptions of police using PPE: participants in all conditions generally perceived the officer favorably. Despite not reaching statistical significance, however, many of the differences in means across conditions still trended in the directions in which we predicted in Hypotheses #1 and #2. For example, participants in the pro-PPE condition typically perceived the officer most favorably, followed by participants in the neutral condition, and then by participants in the anti-PPE condition. These findings suggest several important conclusions.

First, making participants immediately aware of the health benefits of PPE via a fictitious news article may have been enough to help magnify positive perceptions of an officer using PPE (as evidenced by the magnitude of favorable perceptions among participants in this condition). Second, and conversely, making participants immediately aware of the lack of health benefits of PPE via a fictitious news article was not enough to induce completely negative perceptions of an officer using PPE. In this case, participants identified the messaging of their assigned article (i.e., PPE does not present health benefits), yet they still rated the officer more favorably when using PPE. Thus, a shallow manipulation similar to that employed as part of the present research may not be salient enough to dramatically change people’s perceptions about officers who use this equipment during a public health crisis. Indeed, 80% of participants (regardless of condition) agreed or strongly agreed that the police should use PPE whenever possible during the COVID-19 pandemic and participants in the anti-PPE and neutral conditions who inaccurately answered the manipulation check question overwhelmingly specified that they thought the fictitious news article suggested that PPE was beneficial.

Although we did not observe as much variation across our conditions as expected, we found many significant effects for specific items of PPE within conditions. For example, using a surgical mask or N95 mask alone and/or in combination with medical gloves unilaterally enhanced perceptions of the officer. The full-face respirator mask, on the other hand, exhibited more mixed effects. Consistent with Hypothesis #3, we found that using this particular mask alone and/or in combination with medical gloves amplified perceptions of aggression as well as intimidation, and reduced perceptions of friendliness for participants in the anti-PPE condition. We found fewer effects for the face shield, and any perceptual effects that we did observe were positive. Finally, we found that using combinations of PPE elicited further perceptual effects, but that such effects were largely a function of some perceptually salient items of PPE as opposed to the completely additive effect of multiple items.

Implications

The findings from the present research exhibit important implications for both the scholarly and practitioner communities. For example, the present research provides insight into the relevance of awareness for perceptions of police in the absence of formal contact. Consider gloves as one case in point. Gloves have been previously identified as eliciting negative perceptual effects when rated without context and when black in color (Simpson 2020a). Yet, in the context of a public health crisis, gloves are an arguably necessary piece of equipment (WHO 2020d), and our participants seemed to generally agree: we did not observe negative perceptual effects for the (light blue) medical gloves tested in the present research.Footnote 5 Building strong messaging around the benefits of equipment (and the support for such benefits from non-policing entities, like governments and/or health authorities) may thereby help to minimize the potential negative effects that the equipment could otherwise induce for police. In this way, the present research complements previous research that has tested the effects of officer appearance in isolation (e.g., see the work of Simpson) as well as related research that has investigated the effects of subtle manipulations regarding depictions of policing styles on perceptions of police (e.g., see Wozniak et al. 2020).

With that being said, relying upon awareness as a mechanism to dramatically sway opinions about police in the context of publicly prominent topics, like COVID-19 and PPE, may be a challenging task. In these cases, shallow interventions may be able to help magnify perceptual effects consistent with one’s pre-existing beliefs, but much more intensive interventions may be required to actually sway opinions toward the opposite direction of such beliefs. For example, the pro-PPE condition seemed to generally exhibit more favorable perceptions of the officer than the anti-PPE condition, but participants in the anti-PPE condition still generally perceived the officer using PPE as at least somewhat favorable even though they were led to believe that PPE was not beneficial for reducing the spread of COVID-19. We attribute this finding to the prevalence of mainstream messaging which, whether explicit or not, suggests that PPE either offers at least some benefits, or at minimum, no real harms. This challenge of inducing change in perceptions via group manipulations is consistent with the findings of Wozniak et al. (2020) who observed that a very subtle manipulation which experimentally exposed participants to different styles of policing images (e.g., militarized versus community policing versus stop-and-frisk) did not differentially influence their global assessments of police.

In this vein, the present research demonstrates how experimental paradigms can be rapidly mobilized to assess scientific questions of an applied nature. By quickly revisiting questions of perception in this specific pandemic context, the present research was able to help identify the effects of particular equipment during a time of tremendous uncertainty. It would be fruitful for future research to consider how similar paradigms may be implemented to study the effects of other social changes on related outcomes. As society changes, research must adapt and change with it in order to ensure that the evidence base remains current and relevant for policy and practice.

Finally, the findings from the present research offer some practical implications for police who continue to provide frontline services during the COVID-19 pandemic. By educating the public about the rationale for their use of PPE, police may be able to help enhance perceptions of their officers who must use the equipment.Footnote 6 Moreover, by combining their use of such awareness campaigns with other principles like procedural justice (Farrow 2020; Jones 2020; Mazerolle et al. 2012), police may be able to help promote positive perceptions during a time of much unrest. And this may soon become even more important if more extreme public health precautions become necessary. Although PPE has been shown to be helpful for preventing the spread of COVID-19, its use is still not perfect: even with it, police officers have continued to contract the virus. For example, as early as April 2020, more than 2000 employees from the New York City Police Department had contracted the virus (McCarthy and Marsh 2020), and by late July, approximately 440 employees from the Los Angeles Police Department had contracted it (Queally and Rector 2020). Given these numbers, it is expected that public health precautions will continue and may even intensify while policing during the pandemic. The need for these kinds of public health precautions makes education about such precautions particularly important so that perceptions are not compromised in pursuit of health and safety.

In light of the preceding discussion, it is important to still recognize that in the absence of legislation or formal policy, the decision to use PPE is ultimately at the discretion of the officer. And officers may articulate different reasons for why using some items of PPE can present other risks and challenges, including a difficulty to communicate with people whom they may be engaging. For example, if the use of a mask hinders an officer’s ability to effectively communicate with an individual, and such individual then reacts poorly to the officer because of the communication barrier, the use of the mask may complicate the nature of the interaction and amplify the risk of other consequences, including potential force. There are thus other (unmeasured) factors that may be relevant for the officer’s decision to use PPE that are independent of the risk of the virus, and such factors, including officer safety and well-being, should also be included in these kinds of discussions.

Limitations

The present research exhibits several limitations. First, and foremost, we employed a laboratory-style framework to test the effects of PPE and awareness about the utility of such PPE on perceptions of police. Although we enhanced the validity of our stimuli by ensuring that our news articles appeared as authentic as possible and capturing images of current officers in natural environments where members of the public were present but not focal, we recognize that real-world interactions which involve formal contact with police may be more dynamic and subject to greater perceptual pressures. It is also possible that variables which could not be measured as part of the present research, like officer speech and mannerisms, may impact perceptions of police independently of PPE; however, these kinds of variables could not be tested as part of the current experimental paradigm. Future researchers working within this domain should seek to test questions about perceptions in field environments and/or by using live-action stimuli which more closely mirror dynamic interactions.

Second, a sizeable proportion of our sample failed their manipulation check question, particularly in the anti-PPE and neutral conditions. As described earlier, we theorize that this failure rate may be the result of our shallow manipulation. Reading a single news article may not have been salient enough for participants to internalize messaging about such a publicly prominent topic, and therefore, participants may have favored their pre-existing beliefs about COVID-19 and the benefits of PPE over the content of their assigned article (especially when considering that our fictitious articles were intentionally generic and did not make any mention of police). This logic is further substantiated by the findings from a concluding survey question which assessed participants’ opinions about the use of PPE by police: participants overwhelmingly agreed that officers should use PPE whenever possible during the COVID-19 pandemic, even among the anti-PPE and neutral conditions. In this vein, we suspect that the conceptual issue was likely more a result of too shallow of a manipulation than too small of a sample: we would not expect that continuing to oversample these conditions to increase the sample size would improve the success rate for the manipulation check question given our theoretical arguments presented above. With this in mind, future research should employ more qualitative analyses to test dosage effects for interventions aimed at changing perceptions about police and their associated equipment.

Third, and finally, we used images of a single officer who self-identified as male and White as part of the present research. It is possible that different effects may have been observed if different/more officers had been included in our experimental paradigm. With that being said, we do not believe that the use of a single officer limits the value of our findings for at least two reasons. First, our research question was largely exploratory, and our primary focus was to develop an internally valid test of the perceptual effects of PPE in the context of PPE awareness. Second, we do not expect that the effects of individual items of PPE would systematically vary as a function of officer characteristics: although differences may exist in perceptions of officers at baseline, the independent effects of specific items of PPE should not theoretically vary.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has fundamentally changed contemporary society and the ways in which people operate and engage with each other. In order to reduce the risks associated with the virus, police worldwide have developed strategies to maintain service levels and minimize virus exposure. These changes have included emphases on telephone responding, modified work schedules, remote work opportunities, and most importantly, the widespread use of PPE. In fact, the use of PPE by frontline officers may actually be one of the most visible and perceptually salient changes to the criminal justice system induced by the pandemic. Seeing officers routinely use what has traditionally been medical equipment is both novel and important for functionality and perception. The present research employed an experimental paradigm to empirically identify the effects of PPE on perceptions of police among participants exposed to fictitious news articles about the utility of PPE. The results revealed that using PPE exhibits important perceptual implications for police, but that with few exceptions (e.g., the full-face respirator mask), such implications are all positive. By measuring the effects of PPE on perceptions of police, the present research offers important insight into a key piece of the criminal justice system’s pandemic puzzle.

Notes

For example, it should be perceptually favorable for an officer to don a face mask as they enter a store which requests their usage (e.g., see Pringle 2020). Consistent with this logic, police executives have anecdotally cited cases of citizens filing complaints against their officers for not using PPE in certain spaces.

The question was as follows: “The authors of the article suggested that the use of personal protective equipment (e.g., gloves, face masks, face shields, and eyewear) is (a) not helpful for preventing the spread of COVID-19; (b) helpful for preventing the spread of COVID-19; or (c) the authors did not discuss the use of personal protective equipment.”

All procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Board at the university where the experiment was conducted. All participants were advised that the news article in which they read was fictitious during their debriefing at the conclusion of the experiment.

In all of the images, the officer wore their standard issue patrol uniform, which included an operational duty belt, navy blue short-sleeve collared shirt, navy blue pants, and black patrol boots.

We recognize that the medical gloves tested as part of the present research were light blue in color and therefore vary from the black gloves studied in previous research. Nonetheless, we find no negative perceptual effects of these medical gloves, which has important practical implications for police.

For example, a Twitter post by the Los Angeles Police Department dated July 31, 2020 highlighted how officers would be patrolling using PPE. The post stated that officers “will be passing out free masks to Angelenos, and having a conversation about the benefits of wearing one, and the dangers of not wearing one.”

References

Ashby, M. P. (2020). Changes in police calls for service during the early months of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paaa037.

Bell, D. J. (1982). Police uniforms, attitudes, and citizens. Journal of Criminal Justice, 10(1), 45–55.

Bickman, L. (1974). The social power of a uniform. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 4(1), 47–61.

Boyanowsky, E. O., & Griffiths, C. T. (1982). Weapons and eye contact as instigators or inhibitors of aggressive arousal in police-citizen interaction. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 12(5), 398–407.

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2011). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: a new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 3–5.

Carlson, T. (2020). CNN, MSNBC are peddling panic, moral judgment, not science and data, in coronavirus coverage. Fox News. https://www.foxnews.com/opinion/tucker-carlson-cnn-msnbc-are-peddling-panic-moral-judgment-not-science-and-data-in-coronavirus-coverage.

Casler, K., Bickel, L., & Hackett, E. (2013). Separate but equal? A comparison of participants and data gathered via Amazon’s MTurk, social media, and face-to-face behavioral testing. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(6), 2156–2160.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019: information for law enforcement personnel. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/guidance-law-enforcement.html.

Chu, D. K., Akl, E. A., Duda, S., Solo, K., Yaacoub, S., & Shünemann, H. J. (2020). Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 395(10242), 1973–1987.

Cook, T. M. (2020). Personal protective equipment during the coronavirus disease (COVID) 2019 pandemic – a narrative review. Anaesthesia: Peri-Operative Medicine, Critical Care and Pain, 75(7), 920–927.

Darcy, O. (2020). How Fox News misled viewers about the coronavirus. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/12/media/fox-news-coronavirus/index.html.

Durkin, K., & Jeffery, L. (2000). The salience of the uniform in young children’s perception of police status. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 5(1), 47–55.

Farrow, K. (2020). Policing the pandemic in the UK using the principles of procedural justice. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 14(3), 587–592.

French, C. E., McKenzie, B. C., Coope, C., Rajanaidu, S., Paranthaman, K., Pebody, R., Nguyen-Van-Tam, J. S., Higgins, J. P. T., & Beck, C. R. (2016). Risk of nosocomial respiratory syncytial virus infection and effectiveness of control measures to prevent transmission events: a systematic review. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses, 10(4), 268–290.

Halon, Y. (2020). Sean Hannity accuses Democrats of ‘weaponizing’ coronavirus ‘to score cheap, repulsive political points’. Fox News. https://www.foxnews.com/media/sean-hannity-democrats-weaponizing-coronavirus-trump.

Hughes, P. G., Hughes, K. E., & Ahmed, R. A. (2020). Does my personal protective equipment really work? A simulation-based approach. Medical Education, 54(8), 759–760.

Jennings, W. G., & Perez, N. M. (2020). The immediate impact of COVID-19 on law enforcement in the United States. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 690–701.

Johnson, R. R., Plecas, D., Anderson, S., & Dolan, H. (2015). No hat or tie required: examining minor changes to the police uniform. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 30(3), 158–165.

Jones, D. J. (2020). The potential impacts of pandemic policing on police legitimacy: planning past the COVID-19 crisis. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 14(3), 579–586.

Joseph, N., & Alex, N. (1972). The uniform: a sociological perspective. American Journal of Sociology, 77(4), 719–730.

Kraska, P. B. (2007). Militarization and policing: its relevance to 21st century police. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 1(4), 501–513.

Lawson, E. (2019). Trends: police militarization and the use of lethal force. Political Research Quarterly, 72(1), 177–189.

Lindsley, W. G., Noti, J. D., Blachere, F. M., Szalajda, J. V., & Beezhold, D. H. (2014). Efficacy of face shields against cough aerosol droplets from a cough simulator. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 11(8), 509–518.

Malone, K. G. (2020). Police warn coughing on officers during COVID-19 pandemic can be considered assault. CTV. https://bc.ctvnews.ca/police-warn-coughing-on-officers-during-covid-19-pandemic-can-be-considered-assault-1.4890255.

Mazerolle, L., Bennett, S., Antrobus, E., & Eggins, E. (2012). Procedural justice, routine encounters and citizen perceptions of police: main findings from the Queensland Community Engagement Trial (QCET). Journal of Experimental Criminology, 8(4), 343–367.

McCarthy, C., & Marsh, J. (2020). Huge percentage of NYPD cops out sick as coronavirus spreads. New York Post. https://nypost.com/2020/04/06/nearly-20-percent-of-nypd-cops-are-out-sick-during-coronavirus-outbreak/.

Mellis, A. M., & Bickel, W. K. (2020). Mechanical Turk data collection in addiction research: utility, concern and best practices. Addiction, 115(10), 1960–1968.

Mortensen, K., & Hughes, T. L. (2018). Comparing Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform to conventional data collection methods in the health and medical research literature. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33(4), 533–538.

Mukamul, R. (2020). Eye care during the coronavirus pandemic. American Academy of Ophthalmology. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/tips-prevention/coronavirus-covid19-eye-infection-pinkeye.

National Post. (2020). Why a mask won’t protect you from the Wuhan coronavirus. https://nationalpost.com/news/canada/wuhan-coronavirus-mask.

O’Neill, J., Swenson, S. A., Stark, E., O’Neill, D. A., & Lewinski, W. J. (2018). Protective vests in law enforcement: a pilot survey of public perceptions. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 33(2), 100–108.

Paolacci, G., Chandler, J., & Ipeirotis, P. G. (2010). Running experiments on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Judgement and Decision Making, 5(5), 411–419.

Pica, E., Sheahan, C. L., Pozzulo, J., & Bennell, C. (2020). Guns, gloves, and tasers: perceptions of police officers and their use of weapon as a function of race and gender. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 35(3), 348–359.

Pringle, J. (2020). Costco recommends shoppers wear a mask or face covering. CTV. https://ottawa.ctvnews.ca/costco-recommends-shoppers-wear-a-mask-or-face-covering-1.4948490.

Queally, J., & Rector, K. (2020). LAPD officer, a 13-year veteran, dies after contracting coronavirus. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-07-24/lapd-officer-dies-after-contracting-coronavirus-sources-say.

Reicher, S., & Stott, C. (2020). Policing the coronavirus outbreak: processes and prospects for collective disorder. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 14(3), 569–573.

Roberge, R. J. (2016). Face shields for infection control: a review. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 13(4), 235–242.

Simpson, R. (2017). The Police Officer Perception Project (POPP): an experimental evaluation of factors that impact perceptions of the police. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 13(3), 393–415.

Simpson, R. (2019). Police vehicles as symbols of legitimacy. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 15(1), 87–101.

Simpson, R. (2020a). Officer appearance and perceptions of police: accoutrements as signals of intent. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 14(1), 243–257.

Simpson, R. (2020b). When police smile: a two sample test of the effects of facial expressions on perceptions of police. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-020-09386-y.

Singer, M. S., & Singer, A. E. (1985). The effect of police uniform on interpersonal perception. The Journal of Psychology, 119(2), 157–161.

Thomas, J. P., Srinivasan, A., Wickramarachchi, C. S., Dhesi, P. K., Hung, Y. M., & Kamath, A. V. (2020). Evaluating the national PPE guidance for NHS healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinical Medicine, 20(3), 242–247.

Vancouver Police Department. (2020). VPD COVID-19 update. https://vancouver.ca/police/covid-19.html.

White, M. D., & Fradella, H. F. (2020). Policing a pandemic: stay-at-home orders and what they mean for the police. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 702–717.

World Health Organization. (2020a). Q&A: how is COVID-19 transmitted? https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/q-a-how-is-covid-19-transmitted.

World Health Organization. (2020b). Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: implications for infection prevention precautions. https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/transmission-of-sars-cov-2-implications-for-infection-prevention-precautions.

World Health Organization (2020c). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019.

World Health Organization. (2020d). Rational use of personal protective equipment (PPE) for coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331498/WHO-2019-nCoV-IPCPPE_use-2020.2-eng.pdf.

World Health Organization (2020e). Coronavirus prevention. https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_2.

Wozniak, K. H., Drakulich, K. M., & Calfano, B. R. (2020). Do photos of police-civilian interactions influence public opinion about the police? A multimethod test of media effects. Journal of Experimental Criminology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-020-09415-0.

Yesberg, J. A., Bradford, B., & Dawson, P. (2020). An experimental study of responses to armed police in Great Britain. Journal of Experimental Criminology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-019-09408-8.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Chief Neil Dubord and the Delta Police Department for sharing their time and equipment in order to make this project possible. The authors would also like to thank Sam Zacharias for assisting us with the photography for this project. Finally, the authors would like to thank the editorial team and anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments regarding this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Simpson, R., Sandrin, R. The use of personal protective equipment (PPE) by police during a public health crisis: An experimental test of public perception. J Exp Criminol 18, 297–319 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-020-09451-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-020-09451-w