Abstract

Museum visitors are not reflective of the diversity present in communities around the nation. In this study, we investigate the racial and ethnic diversity of art museum participants as well as the potential motivations and barriers to visiting a museum. Using the General Social Survey, we examine race and ethnicity and arts participation in the USA. We find Black individuals are less likely to attend an art museum than white individuals. Certain motivations and barriers to participating may explain part of the lack of diversity. We find Black and Latinx individuals are motivated to participate in art museums for cultural heritage reasons more than white individuals, but race and ethnicity are unrelated to perceiving admission fees as a barrier. This research highlights the urgency in the field to make museums more inclusive.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Discussions of diversity, inclusion, and equity continue to grow in the arts and museums. However, the scholarly focus has been largely on the diversity of boards, employees, and volunteers (Weisinger et al. 2016). While national governments, like the UK, Australia, and Canada, have mandated museums to become more inclusive (Australia Council for the Arts 2020; Hooper-Greenhill 1994; Kinsley 2016; Sandell and Nightingale 2012), American museums have had difficulty finding a consistent path that is welcoming to audiences. In a world aspiring for equality and equity, museums are critically reevaluating their role in society.

Although community connection is a cornerstone of many arts capital projects (Frumkin and Kolendo 2014) and the arts provide a multitude of benefits at both the individual and community levels (e.g., McCarthy et al. 2001; Onyx et al. 2018), participants do not reflect the general population. Overall participation in the USA is at a low rate. Merely 23% of US adults attend an art exhibit every year; 27% of those individuals who participated were white, 17% of individuals were Black, and 16% of individuals were Latinx (National Endowment for the Arts 2019). In this study, we first examine whether race and ethnicity are significant predictors of art museum participation.

We then examine specific motivations for and barriers to arts participation by focusing on the role of cultural representation and cost. While research demonstrates a correlation between museum participation, higher socioeconomic status, and higher levels of education (e.g., Bowman et al. 2019; DiMaggio and Ostrower 1990; Falk 1995; Farrell and Medvedeva 2010; Jun et al. 2008; Phillip 1993), it is unclear whether and to what extent cost may be a potential barrier to participation (Acevedo and Madara 2015; Garibay 2009; Jun et al. 2008; NEA Office of Research & Analysis 2015). In addition, low participation of diverse audiences could be attributed to the insufficient cultural representation on museum walls and in museum halls (Acevedo and Madara 2015; Garibay 2009; Phillips 1993). We will investigate whether admission costs and the lack of representation influence museum participation.

Museums have the potential to serve more people; for that reason it is important to learn who is and is not participating, and why. Engaging a broad audience is vital to the sector and practitioners, as “diversity is a widespread goal among museums,” and can encourage and promote positive change and potentially increase participation numbers (Werner et al. 2014, p. 192). Supporting cultural representation with internal policies and protocols and externally with museum programs and exhibits could motivate diverse audiences to participate (Ostrower 2008). Finally, despite some institutional leaders assuming that admission fees negatively impact the participation of diverse audiences; cost might not be a barrier to some audiences.

The goal of this study is to examine how race and ethnicity correspond to art museum participation and to gain insight into the motivations for and barriers to participation. We begin with a background summary of the museum field, followed by a review of the relevant literature, theory, and hypotheses. Next, we describe the data from the General Social Survey and present our findings, concluding with a discussion of the results and implications.

The Museum Field

The evolution of museums from small private collections to massive public exhibits was not linear, from collecting precious treasures to actively preserving objects to creating educational programming around artworks. The museum model has varied throughout time and place. Still, museums have a history of being exclusive places for the elite few, led by authoritative curatorial voices that were rarely challenged. This narrow focus can sometimes still be seen today; Ostrower (2020) interviewed board members of organizations to illustrate the elitism that persists as wealthy board members often donate or promise works of art to the museums they serve in exchange for network opportunities with prestigious institutions with members of their class. “Yet this same elite status leaves them poorly positioned to serve as the bridge between the organization and wide segments of the community who are outside of their class” (Ostrower 2020, p. 84). Eventually, the museum was reinvented to become a public space with an emphasis on the visitor experience tasked with the production and dissemination of knowledge (Hooper-Greenhill 2010; Simmons 2016). Today, the field moves to reconceptualize traditional conventions and renew the relationship between the organization and its audiences, with the intent of bringing the two closer together to enable a broader appreciation of the museum for all.

Since museum-going has complex roots, underlying variances in cultural and leisure values exist among participants (Falk 1995). One of the main differences in participation could be tied to forms of exclusion, suggesting there are numerous approaches to museum participation (DiMaggio and Ostrower 1990; Ostrower 2008; Phillip 1993). In the USA, museums have a history of racial discrimination; Black Americans were excluded from visiting some cultural sites until the start of the Civil Rights Movement when public spaces like museums began to desegregate (DiMaggio and Ostrower 1990). The Hispanic population has also experienced modern forms of exclusion from museums, noting a lack of bilingual services and interpretation, as well as Hispanic representation in staff, content, and perspective (Stein et al. 2008). Faced with historic issues of segregation and exclusion of Black individuals, and a growing Latinx population that will encompass 30% of the nation’s population by 2050 (Farrell and Medvedeva 2010). Museums continue to contend with balancing institutional missions and a focus on their audiences. While museums no longer explicitly discriminate, they must recognize that their audiences are not diverse. This will be the first step for organizations to truly move toward practicing more inclusive approaches.

In the USA, the overarching mandates for museums are the national policies that apply to all businesses and organizations. In the 1970s, as federal funding shifted to include racially underrepresented groups and women, museums were also required to have diverse staff members (Faden 2007). Fath Davis Ruffins, curator of Black History at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, was one of three people hired under the affirmative action program (Sandell and Nightingale 2012). Ruffins recalls: “historically what has been collected at the Smithsonian has been because a person was really interested in that particular thing” (Sandell and Nightingale 2012, p. 19). In other words, if museum staff was not diverse, the museum’s collection was not diverse, and what was chosen to be displayed was limited; ultimately, perpetuating exclusion in the field (Hooper-Greenhill 1994). Although museums have not completely ignored Latinx and Black artists or stories; they have been underrepresented in museum spaces, and museum staff have struggled to present relevant offerings (Berger 1992).

Representative bureaucracy, the idea that government should reflect the people it serves (e.g., Kingsley 1944; Mosher 1968; Krislov 1974; Selden 1997), can be extended to museums, where museum leadership and staff reflect society for all people to feel museums are relevant to them. Passive representation is the extent to which the bureaucracy reflects the population, while active representation is the extent to which employees act on behalf of those represented. The move from passive to active representation often depends upon discretion, policy congruence between the bureaucrat and the social or group identity, and for women, the issue tends to also be gendered (Riccucci and Van Ryzin 2017). While representative bureaucracy theory originated in government, it may extend to other public-serving organizations like museums. Diverse staff could actively represent their racial and ethnic groups by advocating for culturally representative artwork, exhibits, and programming.

Yet museum staffs are far from representative. In 2014, the national museum professional organization, American Alliance of Museums (AAM), released its first diversity and inclusion policy statement. Despite the museum sector’s attention to the idea of inclusion, museums have not been able to diversify their workforce (Kinsley 2016). In 2015, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation found from a demographic survey of art museum staff that 76% of the workforce was white with only a slight change in 2018–72% (2019). There is value in boards that reflect their community (e.g., Bernstein and Bilimoria 2013; Gazley et al. 2010; Solebello et al. 2016); therefore, there is value in museum leaders and employees that reflect the population served; this ensures all people feel represented.

Theory and Hypotheses

Critical race theory (CRT) provides an important lens to consider in explaining the race and ethnic gap in museum participation. CRT argues that racial power imbalances due to the history of slavery, segregation, and racism in the USA persist over time and permeate throughout society. Through this lens, Kraehe and Acuff (2013) argue, “White Euro American experiences often have been the standard by which all other racial groups’ experiences are measured, thus, the experiences and interests of Whites are normalized” (p. 297). CRT provides a much-needed lens to examine administrative decisions, for instance, when dealing with hiring practices or affirmative action policies, and the hidden influence of such legislations. Even with thoughtful policies, internal bias can exist within an institution (Sandell and Nightingale 2012). For example:

[…] at MoMA a white, female supervisor asked us, if we knew anyone who would be “a great addition to the team.” I recommended two Latinx colleagues who are amazing, bilingual educators and have several years of experience specific to the position. Only one got an interview and wasn’t ultimately hired […] But ultimately it’s more important to maintain the status quo and keep hiring people who look and think like the administrative staff, or who can be molded to do so (Change the Museum 2020).

A CRT framework allows museum leaders and professionals to consider museum practices and programs while taking into account diversity and inclusion.

We will approach race and ethnicity together; accepting that both concepts are fluid, complex constructs that are deeply connected to the individual’s idea of self. We understand race as a reference to the physical characteristics of a person and ethnicity as the cultural or national characteristics of a collection of people (Kendall, Linden & Murray, 2008). Race and ethnicity are vital with regard to how different aspects of arts and culture are perceived and experienced by different individuals (Hall 2010).

Ostensibly, the importance of knowing a visitor’s race is that people of the same race share some of the same history, experiences, language, and beliefs—which are actually defining elements of a culture. It is these cultural characteristics that are relevant to connecting with museum visitors presumably affecting what they already know or believe to be true, what interests and motivates them, and how to best communicate with them (Werner et al. 2014, p. 193).

Furthermore, as the racial and ethnic composition of the American population continues to shift and become more diverse, museums have no choice but to become institutions that actively engage with diverse populations and practice inclusivity, or risk becoming irrelevant to broad sectors of the community.

Diversity encompasses visible and nonvisible differences including culture, socio-economic status, and values; with the intent to celebrate, promote, and respect those differences (Sandell and Nightingale 2012). An inclusive approach suggests that museums actively address barriers, especially for people at risk of exclusion (Kinsley 2016). For museums, inclusion can be addressed through the intentional process of combating exclusion through cultural, social, political, and economic means, demonstrating respect for all members of society (American Alliance of Museums 2018; Coleman 2018).

Arts Participation: The Role of Exclusion

Exclusion from educational and economic systems is mirrored in the exclusion from museums (Kinsley 2016). Individual educational attainment is connected to the way people think about, participate in, and enjoy a variety of art and cultural forms (DiMaggio and Useem 1980; DiMaggio and Mukhtar 2008; Falk 1995; Phillip 1993; Reeves 2015; NEA 2015). Falk (1995) found that educated individuals were nearly twice as likely to visit as those with less education. Relatedly, DiMaggio and Mukhtar (2008) found a decline in arts participation from high school graduates between 1982 and 2002. Interestingly, participation patterns can be passed from one generation to the next; well-educated parents tend to invest in their children's education and are more likely to value art activities and participate together than parents of lower socioeconomic status (Bourdieu 1973; Di Maggio and Useem 1980).

Socioeconomic factors play a key role in arts participation. Variations in arts participation extend to income and occupation (DiMaggio and Useem 1980; Erickson 2008; Falk 1995; Jun et al. 2008; NEA 2015). Research has found that as personal income increases the number of barriers to participation decreases (Falk 1995; Jun et al. 2008). The NEA (2015) reports 78% of people who named cost as a barrier to participation identified it as the most important barrier they faced when deciding whether to participate. In most museums’ visitors pay a fee for access or improved access; therefore, people with lower incomes might have limited or no access, and people with higher incomes have a greater array of opportunities (Erickson 2008). Understanding the current demographics, values, needs, and interests and how these aspects contribute to visitor participation is increasingly important to a museum’s success.

Race, Ethnicity, and Arts Participation

Research finds the typical profile of a museum-goer in the USA is white, and visitors who identify as Black or Latinx have notably lower rates and are underrepresented in museum participation (Coffee 2008; Farrell and Medvedeva 2010; National Endowment for the Art 2015; NEA Office of Research & Analysis 2015; Phillip 1993). Using the Survey of Public Participation in the Arts, DiMaggio and Ostrower (1990) found 23.4% of white Americans visited an art museum or exhibit compared to only 13.1% of Black Americans. Based on interviews with 333 Black individuals, Falk (1995) found that 48.9% of respondents had visited a museum, but this was only once every several years. Race and ethnicity seem to continue to influence arts participation in the USA. However, few examine both race and ethnicity and disentangle race and ethnicity from socioeconomic factors.

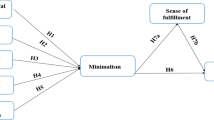

Due to the history of exclusion and the continued lack of representation in museums, Black individuals may continue to feel excluded from and underrepresented in art museums and the arts. Based on descriptive reports of a racial gap in arts participation and the historical exclusion of racially underrepresented groups, we hypothesize:

H1a

Black individuals are less likely to participate in art museums than white individuals.

H1b

Latinx individuals are less likely to participate in art museums than white individuals.

Reasons for Participation: The Role of Cultural Representation

Cultural representation “refers to the extent to which an individual’s cultural heritage is represented within the mainstream culture” (Azmat and Rentschler 2017, p. 377). This concept consists of producing and sharing meaning and knowledge with others (Hall 2010). A museum exhibit could be described as a system of representation, producing meaning through word choice, storytelling, or imagery, validating works of art and objects through a particular perspective such as art history, anthropology, or science (Hall 2010). Historically, museums made some cultures visible and others invisible. Each decision to display one work of art over another is a choice on how to represent art and culture and each choice has a consequence, especially between those who are doing the exhibiting and those who are being exhibited, excluded, or misrepresented (Hall 2010). Rentschler et al. (2017) highlight the importance of relationship building between audiences and organizations. Since most visitors feel comfortable in museums regardless of race (Falk 1995; Jun et al. 2008), perhaps the race and ethnic gap in participation is due to the shortage of cultural representation in museums (Acevedo and Madara 2015; Garibay 2009).

Research illustrates the role of cultural representation for both Black and Latinx populations. Ostrower (2008) determined that “expanding the notion of diversity to encompass motivations and experience would strengthen our characterizations and interpretation of people’s involvement in culture and help managers and policymakers craft more effective initiatives to expand it” (p. 86). Using findings from the 2004 Urban Institute’s national survey of cultural participation, Ostrower (2008) found 50% of Black and 43% of Latinx survey respondents were more likely than white respondents to express a desire to learn about or celebrate their cultural heritage as a motivation to participate. Stein et al. (2008) found Latinx visitors indicated feeling a strong personal connection to Aztec, Maya, and Spanish collections. Both US-born and foreign-born Latinx individuals highly valued connecting to their culture in a museum space (Acevedo and Madara 2015; Garibay 2009; Stein et al. 2008). Furthermore, Latinx audiences revealed that bilingual labels were essential to their museum experience (Acevedo and Madara 2015; Stein et al. 2008). Likewise, Phillips (1993) found that Black individuals ranked cultural resources and representation of “tribal costumes” higher than white individuals (p. 301).

I get really excited when there’s an exhibit about black culture, which means those exhibits don’t come around very often […] That’s what would draw me into museums more. Exhibits about the art and culture of nonwhite people. Because usually when I see people that look like me on museums walls they are wearing shackles and chains. Which is important. I do want to learn about the painful parts of our history, but I’d like to see more positive things as well. (Jones 2016).

People participate in art museums for a variety of reasons, but cultural representation is a primary motivator for racially underrepresented groups. Diverse audiences value museums that are culturally relevant and reflect the communities they serve. Based on the importance of cultural representation, we hypothesize:

H2a

Black individuals are more likely to be motivated to participate in art museums due to cultural heritage reasons than white individuals.

H2b

Latinx individuals are more likely to be motivated to participate in art museums due to cultural heritage reasons than white individuals.

Barriers to Participation: The Role of Cost

In addition to motivations to participate in museums, some may want to participate but are unable due to a variety of factors. The cost of admission is often cited as one of the most common barriers to participation (Acevedo and Madara 2015; Garibay 2009; Jun et al. 2008; NEA Office of Research & Analysis 2015), but people also face social, ability, and personal barriers (Kottasz 2015). Admission prices and policies can be associated with issues of economic efficiency and visitor equity (Bailey and Falconer 1998). Perhaps unsurprisingly, people at higher-income levels were just as likely as people at lower-income levels to attend art exhibits on free admission days (NEA Office of Research & Analysis 2015). However, Bowman et al. (2019) found that on free admission days the sample included significantly higher percentages of Latinx and Black participants and a significantly lower percentage of white participants. While free admission days could potentially increase audience diversity, the occasional free day will not promote inclusion or attract visitors who lack motivation (Bowman et al. 2019). The relationship between admission cost and arts participation is far from simple.

Applying a CRT perspective, perhaps cost disproportionately burdens some racial and ethnic groups more than others. Descriptive findings on Latinx visitors suggest that affordability and cost were important criteria for participation (Acevedo and Madara 2015; Garibay 2009; Stein et al. 2008). Budget constraints are real for some visitors, but it is unclear whether removing admission fees would benefit diverse audiences. Consequently, we examine cost as a barrier to participation, hypothesizing:

H3a

Black individuals are more likely to consider the cost of admission as a barrier to participating in art museums than white individuals.

H3b

Latinx individuals are more likely to consider the cost of admission as a barrier to participating in art museums than white individuals.

Methods

Data

This study draws upon data from the 2016 General Social Survey (GSS), a national project from the independent research organization NORC at the University of Chicago that includes a Cultural Module with questions pertaining to museum and arts participation. A total of 4327 adults were interviewed from a random selection of households from across the USA with a response rate of 61.3% (Smith et al. 2016). The total number of cases varies for each dependent variable. We first examine how race and ethnicity relate to arts participation with a sample of 1159 that were asked the Cultural Module questions. Next, we examine how race and ethnicity influence whether and the extent to which cultural heritage is a motivation for arts participation with a sample of 243 respondents who attended an art exhibit in the past year and responded to the motivation questions. Lastly, we examine cost as a barrier to participation with a sample of 119 respondents who wanted to attend an art exhibit in the past year but were unable and responded to the barrier question.

Dependent Variables

We first examine the relationship between race and ethnicity and arts participation and then among those who attend the arts, cultural heritage as a motivation for attending, and among those who were interested in attending but unable, cost as a barrier. The first dependent variable, arts participation, is an indicator variable for the question: “During the last 12 months, did you go to an art exhibit, such as paintings, sculpture, textiles, graphic design, or photography?” with yes coded as 1 and no coded as 0. Nearly a third (32%) of the sample attended an art exhibit in the past year.

People may participate in the arts for several reasons. For our second dependent variable, we examine whether and the extent to which cultural heritage is a motivator. Here, respondents were asked: “How big a reason was wanting to learn about or celebrate your or your family's cultural heritage in your decision to attend this exhibit? Was it a major reason, a minor reason, or not a reason at all?” We examine how factors influence cultural heritage being a minor or major reason compared to not a reason at all. This variable ranges from 1, not a reason at all, to 3, a major reason, with an average of 2.65 and a standard deviation of 0.64.

Lastly, while people consider many factors when deciding to participate in the arts, they may also face barriers to participation. To examine cost as a barrier, we use the following question: “Thinking about the most recent exhibit you wanted to attend but did not, which of the following factors were important in your decision not to attend?” with those who indicated “Cost too much” coded as a 1 for cost as a barrier (29% of respondents) and a 0 otherwise.

Independent Variables

The key independent variables are indicators for race and ethnicity. For race, indicator variables are included for Black and other compared to white, the excluded reference group. As shown in Table 1, 75% of the sample is white, 18% Black, and the remaining 7% identify with other racial groups. For ethnicity, we include an indicator for Latinx which takes on a 1 if the respondent identified as Spanish, Hispanic, or Latino/a (8% of the sample), and a 0 otherwise. Descriptive statistics may be found in Table 1.

In our sample, Latinx and Black respondents have the lowest rates of arts participation, 17% and 25.6%, respectively, compared to 34.3% of white respondents. For those who participated in the arts, 16.7% of Black respondents and 44.4% of Latinx responses reported cultural heritage as a major reason compared to only 7% of white respondents. For those who were unable to participate in the arts, 33.3% of Black respondents and 42.9% of Latinx respondents cited cost as a barrier compared to 26.4% of white respondents. The cross-tabs of our key independent and dependent variables may be found in Table 2.

Drawing upon the literature on arts participation, we control for several demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, including sex, age, number of children, marital status, education, income, social class, and location. Since age influences participation (DiMaggio and Ostrower 1990), the age of respondents is included as control variables, which ranges from 18 to 89 with an average of 49. We also control for sex with an indicator variable for female that takes on a 1 if the respondent is female and a 0 if the respondent is male. On free admission days, Bowman et al. (2019) found there was a greater proportion of groups with children who attended the museum in their study; therefore, we include the number of children ranging from zero to eight. Researchers also found that the group size and the notion of having someone with whom to visit a museum can be a determinant of participation (Bowman et al. 2019; Garibay 2009; NEA Office of Research & Analysis 2015); hence, we control for marital status. We include an indicator variable for married, which takes on a 1 if an individual is married and a 0 otherwise, where nearly 41% of the sample is married.

In addition to demographics and family characteristics, we include socioeconomic variables that are often associated with arts participation, such as education (DiMaggio and Ostrower 1990). Education is measured as an ordinal variable ranging from 0, less than high school, to 4, graduate degree. Since cost plays a principal role in this investigation, and class influences arts participation and involvement (e.g., Ostrower 2020; Di Maggio and Useem 1980; Reeves 2015), we controlled for income using total family income ranging from 1, less than $1000–12, $250,000, and social class. We use the question: “If you were asked to use one of four names for your social class, which would you say you belong in: the lower class, the working class, the middle class or the upper class?” to measure social class that ranges from 1, lower class, to 4 upper class. Lastly, Jun et al. (2008) suggest that reasons for nonparticipation included inconvenient locations, difficulty getting to the location, and not wanting to go to the location. While GSS includes US Regions, the part of the country one lives in might have less of an influence on arts participation compared to the prevalence of the arts in one’s location. Therefore, we use the question: “Which of the categories on this card comes closest to the type of place you were living in when you were 16 years old?” with the options: country, nonfarm; farm; town less than 50,000; 50,000–250,000; big-city suburb, and city greater than 250,000 residents. We include this as an ordinal variable ranging from 1, country, nonfarm, to 6, large city, as a proxy for urbanicity.

Model

We now turn to analyzing the relationship between race and ethnicity and arts participation. Our first model uses logistic regression to examine how race and ethnicity influence arts participation or whether the respondent attended an art exhibit in the past year for the entire sample. We then examine a subsample of respondents who attended an art exhibit in the past year as those respondents were asked about their motivation to participate. Our second model uses multinomial logistic regression to examine how race and ethnicity influence whether and to what extent cultural heritage was cited as a reason for participation. Lastly, we examine a subsample that wanted to participate in the arts but was unable. Our third model employs logistic regression to examine the influence of race and ethnicity on whether the cost was cited as a barrier to participation.

For our logistic regression models, models 1 and 3, we report odds ratios that measure how many times the odds of occurrence are for each unit increase or decrease in the independent variable. For our multinomial logistic model, model 2, we report the relative risk ratio which is the odds of reporting one category compared to the reference category. Note both odds ratios and relative risk ratios are always positive, where values over 1 indicate an increase in odds/risk and values under 1 indicate a decrease in odds/risk. All models include robust standard errors.

Results

The logistic regression analysis results for model 1 are presented in Table 3. The results partially support the first hypothesis on racial and ethnic differences in arts participation as we find a significant gap between Black and white arts participation, but not for Latinx. Findings suggest that Black individuals are 32% less likely to attend an art exhibit than white individuals. The results for other racial groups and Latinx individuals are inconclusive. Other racial groups do not have significantly higher nor lower attendance rates than white individuals, which is likely due to the multiple racial groups included in the other category. In partial support of our first set of hypotheses, Black individuals are less likely to attend art exhibits than white individuals, even when controlling for a variety of socioeconomic factors.

In addition, the results show the influence of resources on arts participation such as higher income, social class, and higher levels of education increase the likelihood of participation. Meanwhile, the chances of attending an art exhibit decrease with the number of children and marriage. These results support prior work on the exclusion of arts participation based on resources and the difficulties families face in participating.

To further test the influence of race on arts participation and disentangle this influence from socioeconomic factors, like education, we repeat the analysis with the inclusion of an interaction variable of two indicators: Black and college degree. As shown in model 1b below, the interaction variable is not significant. However, education and race remain significant. With education and race significantly and independently influencing arts participation, cultural inclusion seems to be what matters for Black patrons.

Supporting the second set of hypotheses, the results for model 2 in Table 4 demonstrate both Black and Latinx individuals are more likely to attend an art exhibit to celebrate cultural heritage than white individuals. Black individuals cite cultural heritage as a major reason four times as likely and a minor reason three times as likely as white individuals. Latinx individuals are more than eight times as likely to cite cultural heritage as a major reason for attending an art exhibit compared to white visitors. Cultural heritage is a significant motivation for Black and Latinx groups to participate in the arts.

The results for model 3 in Table 5 fail to support our third set of hypotheses. There are no statistically significant differences in citing cost as a barrier to arts attendance across racial and ethnic groups. Not surprising, income and social class play a significant role. Individuals with higher levels of income and reporting higher-level social classes are less likely to report cost as a reason for not participating in the arts. Also, location may play a role as may the number of children. This makes intuitive sense as larger families would have to pay a higher cost of admission if bringing their children. However, cost is not a barrier to increasing participation among racially underrepresented groups.

Discussion

If American museums intend to fulfill their public-serving missions, considerations must be made as to how their practices support or discourage participation. Museums are not removed from society, but rather important stakeholders in the cultural landscape, with actions that impact. In this study, we investigated the relationship between race and ethnicity, and arts participation while focusing on barriers and motivations. We discovered Black individuals are less likely to participate than white individuals, and racially and ethnically diverse visitors who identify as Black and Latinx are highly motivated to participate by cultural heritage reasons. Moreover, we found the cost of admission is not a significant deterrent to arts participation across racial and ethnic groups.

Race and ethnicity are critically important in determining how different aspects of leisure activities, like museum-going, are perceived and experienced (Dawson and Jensen 2011). While it is crucial not to create homogenous constructs (Falk 2009; Phillips 1993), visitor characteristics such as race and ethnicity can account for lower museum participation rates. The study found Black individuals are significantly underrepresented. In line with critical race theory, the history of exclusion for Black individuals extends into the arts and persists today.

Our findings support prior research on socioeconomic inequities in museum participation in addition to racial inequities. People with greater resources, like income and education, are more likely to participate, while those with greater obligations, like families, are less likely to participate. Similar to past work (DiMaggio and Ostrower 2008; Falk 1995), the findings reveal that higher income and higher levels of educational attainment are indicators for participation. Furthermore, Jun, Kyle, and O’Leary (2008) also discovered that having more children increased family responsibility and therefore decreased the likelihood of participation. Much like other areas in mission-driven organizations, such as volunteering, individuals with greater resources and status continue to be likely to participate (Dean 2016; Piatak 2016; Piatak et al. 2019).

Perhaps most importantly, this study revealed Black and Latinx individuals were overwhelmingly motivated to participate due to cultural heritage reasons, confirming work by Ostrower (2008). The literature points to historical exclusion and a lack of representation as reasons for lower participation of diverse audiences (DiMaggio and Ostrower 1990; Ostrower 2008; Phillips 1993; Stein et al. 2008). Museums reinforce attitudes and beliefs of belonging and understanding, and cultural representation can take shape in museum spaces through exhibits or programming. This illustrates Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital, “the symbolic wealth that constitutes ‘legitimate culture’” (Bourdieu 1973, p. 492), maintaining that lack of cultural representation in museums results in low participation of diverse individuals. In line with representative bureaucracy (e.g., Kingsley 1944; Mosher 1968; Krislov 1974; Selden 1997) and calls to diversify boards (e.g., Bernstein and Bilimoria 2013; Gazley et al. 2010; Solebello et al. 2016), it is advantageous when museum staff reflect the populations they serve (Hall 2010). Lastly, participating due to cultural heritage reasons often involves other people, a spouse or family; this conclusion was also reflected in both the literature and our findings (Bowman et al. 2019; Farrell and Medvedeva 2010; Stein et al. 2008). Future research should examine the influence of other motivating factors as well as diverse collections and staff and the relevance to the communities they serve.

The cost of admission alone is not a barrier to participation (Kinsley 2016). We found no significant differences in reporting cost as a barrier to participation across racial and ethnic groups. Nevertheless, museums must be mindful of unintended biases and be consistent when constructing pricing policies (Bailey et al. 1998); because for individuals with lower levels of income and of lower-level social classes, cost can be an important consideration when deciding whether to participate. Similar to our results, Erickson (2008) found that individuals with lower incomes and status found more barriers to participation. Location may play a role as may the number of children. Future research should examine potential barriers across more specific racial groups in pursuing and targeting diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts.

The contributions made from this study to the literature are timely and relevant. While the conversation surrounding this topic is active and at the forefront of the field, there is a void of useful research in this area. For the sector to make progress, national studies focusing on Black and Latinx groups must be prioritized. As the population in the USA becomes more diverse and multicultural, museums will need to invest in learning about all people in their communities.

As in most studies, our research is not without its limitations. First, individual decisions, such as arts participation, are motivated by a wide array of factors. Second, the challenge of using a pre-existing dataset such as the GSS requires working with the variables available. For instance, the sample sizes are too small to examine arts participation and the motivations and barriers across all racial groups. Also, certain racial groups may also be motivated by cultural representation, such as Asian or Native American, that may not be found with the aggregate other racial group. Ideally, there would be a dataset that includes museum-specific behaviors and attitudes such as an individual’s opinions, with a wide range of demographic data. There is a clear need for more research on racial differences in museum participation. Moreover, while demographics help museums understand their visitors, research should continue to extend the scope of visitor research to include a broader context of museum visitation; for instance, incorporating cultural issues. Museums can also research their communities instead of limiting themselves to only querying their current participants.

Conclusion and Implications

Museums do so much for individuals in their communities; they ignite curiosity, share ancient artifacts, and tell stories from the past, present, and future. Nonetheless, visitors should expect more. Museums must move to transcend their traditional roles of collecting, preserving, and educating to have a meaningful social place in society. Institutional policies such as pricing, staffing, collecting, and programming influence visitation; therefore, museums need to continue working toward understanding community demographics, be mindful of unexpected barriers, and seek to comprehend visitors’ motivations.

Recommendations for Practice

Institutional Change

For museums attempting to welcome diverse audiences, leaders and staff need to recognize who participates and who does not, and focus on addressing motivations and barriers connected to participation. The goal of the culturally representative museum is to integrate change by incorporating inclusive goals into their mission and daily operations. For some institutions, diversity and inclusion training, committees, policies, or statements could help build internal awareness and move toward creating actionable goals. For other museums, identifying potential areas of growth in their mission, strategic plan, and audiences might be a start. Ultimately, to achieve lasting change museums must consider diversifying staff. Economic realities make careers in the museum field challenging. Institutions can end unpaid internships and prioritize a range of skills like knowledge of cultural diversity, local movements, community organizing, or bilingualism in their hiring process. Regardless of the method, museums can adapt and make clear efforts toward creating an institutional culture that is truly welcoming.

The primary advantage of an inclusive approach is the expansion of the museum’s role and relevance in society; pushing museums to act as facilitators of social change. The antiquated approach to cultural representation is diversity; celebrating world cultures, in which the museum continues to be the curator of differences and similarities (Coleman 2018). An inclusive approach to representation supports community engagement, while museum professionals act as facilitators of dialogue. Museums can commit to identifying how they connect to relevant community issues regardless of their collections or missions. Inclusion is a slow, institutional process that moves beyond diversity and enters the realm of social change and equity (Coleman 2018).

Representation

Cultural representation in museums has often centered on celebrating a culturally specific holiday or heritage month; however, having an annual program where people can ‘see’ themselves represented in the museums is problematic (Kinsley 2016). Broad generalization can deter from developing an accurate understanding of cultural specificity or achieving inclusion (Coffee 2008). Instead, museums can be strategic in building networks and fostering empathy. Museums must aim to tell stories and create experiences that dismantle racism rather than putting it on display (Adams 2017). Embracing a democratic outlook could include forming community advisory committees that are responsible for providing guidance to curatorial and educational departments (Kinsley 2016), identifying artists of color to collaborate with, offering avenues for people to build new networks and interact with others, or stepping aside to allow people in the community to be experts of their own stories (Azmat and Rentschler 2017). These examples might be time-consuming; however, they support the creation of relationships between the museum, audiences, and the community.

Building connections means listening and responding. Moreover, it does not take an incredible amount of time or money to start making connections with visitors or potential visitors. Staff can observe problems and concerns relevant to the community and respond by joining local initiatives or by being involved in current local discussions (Incluseum 2014). Museums can look for opportunities to serve as a forum for community issues; activating museum spaces as places for discussion or collaboration with civic organizations in the area (Incluseum 2014), the possibilities are endless.

An inclusive approach to cultural representation may include museum staff telling diverse stories by using collections and exhibits to present knowledge held by people of color because of lived experiences (Adams 2017). At the Levine Museum of the New South (2017) in Charlotte, North Carolina, a recent exhibit was “co-created with activists and law enforcement, the media, students, clergy and civic leaders. K(NO)W Justice K(NO)W Peace explores the historical roots of the distrust between police and community, tells the human stories beyond the headlines, and engages viewers in creating constructive solutions.” The exhibit was extended several times and ran for three years. Another example of cultural representation in museums was the establishing of The National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, DC; dozens of people from Native communities were consulted as advisors to assist the museum in developing its inaugural exhibits (Coffee 2008). Finally, at the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center, representation is spelled out in their Culture Lab Manifesto: “Prioritize local artists, participants, and organizers. Nothing about communities without those communities” (Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center 2020). This belief and approach is incorporated into exhibits and programming, such as their current talk show style social media program entitled Heritage iRL. These examples demonstrate not only that co-creation between museum and community is feasible but that audience’s value representation in museum spaces.

Admission

Free or low-cost admission policies will not lead to inclusion. Cost is but one barrier in addition to ability, social, and personal barriers (Kottasz 2015). Inclusion and welcoming diverse audiences go beyond removing one single financial barrier and drive the museum toward a holistic view of all barriers particularly for the people previously ignored or excluded (Kinsley 2016). Museums might consider combining low-cost or free admission with a direct focus on making the museum approachable to visitors who are motivated by cultural heritage programs or exhibits. Additionally, museums may vary the days and times that are free or low cost to include more regular weekends and weekdays as not to exclude any population that might not be available to visit during a certain time or day. Museums could also investigate whether offering different admission tickets might incentivize visitors, such as multiday or family passes for a discounted price (Bailey and Falconer 1998). Removing admission fees is not enough. Museums can focus on access and inclusion by placing value in the unique experiences they offer such as educational programming or being a place for family and friends to gather. Collaborating with different organizations and groups in the community to share opportunities and communicate to everyone why they should participate despite the cost.

Many museums across the nation are working diligently to be more welcoming; however, the lack of diversity in museum audiences can no longer be overlooked. Museums must identify blind spots, and the public must hold museums accountable. We must insist museums take a conscious and visible approach to inclusion in a manner that is not superficial but woven deeply into the institution’s core.

References

Acevedo, S. & Madara, M. (2015). The Latino experience in museums: An exploratory audience research study. Retrieved from http://www.contemporanea.us/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Latino-Experience-in-Museums-Report-Contemporanea.pdf

Adams, M. A. (2017). Deconstructing systems of bias in the museum field using critical race theory. Journal of Museum Education, 42(3), 290–295.

American Alliance of Museum (2018). Facing change: Insights from the American Alliance of Museums’ diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion working group. Retrieved from:https://www.aam-us.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/AAM-DEAI-Working-Group-Full-Report-2018.pdf

Australia Council for the Arts (2020). Creating our future: Results of the national arts participation survey. Retrieved from https://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/research/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Creating-Our-Future-Results-of-the-National-Arts-Participation-Survey-PDF.pdf

Azmat, F., & Rentschler, R. (2017). Gender and ethnic diversity on boards and corporate responsibility: The case of the arts sector. Journal of Business Ethics, 14, 317–336.

Bailey, S. J., & Falconer, P. (1998). Charging for admission to museum and galleries: A framework for analyzing the impact on access. Journal of Cultural Economics, 22, 167–177.

Berger, M. (1992). How art becomes history: Essays on art, society, culture in post-new deal American. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

Bernstein, R., & Bilimoria, D. (2013). Diversity perspectives and minority nonprofit board member inclusion. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 32(7), 636–653.

Blessett, B. (2020). Urban renewal and “Ghetto” development in Baltimore: Two sides of the same coin. The American Review of Public Administration, 50(8), 838–850.

Bourdieu, P. (1973). Cultural reproduction and social reproduction. London: Tavistock.

Bowman, C. D. D., Adkins, A., Owen, B. L., Rogers, K. J., Escalante, E., Bowman, J. D., et al. (2019). Differences in visitor characteristics and experiences on episodic free admission days. Museum Management and Curatorship, 34(1), 1–18.

Change the Museum. (2020). Retrieved from https://www.instagram.com/p/CG0jum8FD02/

Coffee, K. (2008). Cultural inclusion, exclusion and the formative roles of museums. Museum Management and Curatorship, 23(3), 261–279.

Coleman, L. E. (2018). Understanding and implementing inclusion in museums. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Dawson, E., & Jensen, E. (2011). Towards a contextual turn in visitor studies: Evaluating visitor segmentation and identity-related motivations. Visitor Studies, 14(2), 127–140.

Dean, J. (2016). Class diversity and youth volunteering in the United Kingdom: Applying Bourdieu’s habitus and cultural capital. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 45(1_suppl), 95–113.

Di Maggio, P., & Useem, M. (1980). The arts in education and cultural participation: The social roles of aesthetic education and the arts. The Journal of Aesthetic Education, 14(4), 55–72.

DiMaggio, P. J. (1987). Cultural entrepreneurship in Nineteenth-Century Boston. In P. J. DiMaggio (Ed.), Nonprofit enterprise in the arts: Studies in mission and constraint (pp. 41–59). New York: Oxford University Press.

DiMaggio, P., & Mukhtar, T. (2008). Art participation as cultural capital in the United States 1982–2002. In S. J. Tepper & B. Ivey (Eds.), Engaging art: The next great transformation of America’s cultural life. New York: Taylor & Francis Group.

DiMaggio, P., & Ostrower, F. (1990). Participation in the arts by black and white Americans. Social Forces, 68(3), 753–778.

Erickson, B. H. (2008). The crisis in culture and inequality. In: S.J. Tepper & B. Ivey (Eds.), Engaging art: The next great transformation of America's cultural life. New York: Routledge, pp 343–363.

Faden, R. (2007). Museums and race: Living up to the public trust. Museums and Social Issues, 2(1), 77–88.

Falk, J. (1995). Factors influencing African American leisure time utilization of museums. Journal of Leisure Research, 27(1), 41–60.

Falk, J. (2009). Identity and the museum visitor experience. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Farrell, B., & Medvedeva, M. (2010). Demographic transformation and the future of museums. Washington, DC: The AAM Press.

Frumkin, P., & Kolendo, A. (2014). Building for the arts: The strategic design of cultural facilities. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Garibay, C. (2009). Latinos, leisure values, and decisions: Implications for informal science learning and engagement. The Informal Learning Review, 94, 10–13.

Gazley, B., Chang, W. K., & Bingham, L. B. (2010). Board diversity, stakeholder representation, and collaborative performance in community mediation centers. Public Administration Review, 70(4), 610–620.

Hall, S. (2010). Representation cultural representations and signifying practices. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Hooper-Greenhill, E. (1994). Museums and their visitor. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hooper-Greenhill, E. (2010). Changing values in the art museum: Rethinking communication and learning. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 6(1), 9–31.

Incluseum. (2014). Joint statement from museum bloggers and colleagues on Ferguson and related events. Retrieved from https://incluseum.com/2014/12/22/joint-statement-from-museum-bloggers-colleagues-on-ferguson-related-events/

Jones, K. (2016). Visitors of Color. Retrieved from https://visitorsofcolor.tumblr.com/page/3

Jun, J., Kyle, G. T., & O’Leary, J. T. (2008). Constraints to art museum attendance. Journal of park and recreation administration, 26(1), 40–60.

Kendall, D., Linden, R., & Murray, J. L. (2008). Sociology in our times: The essentials, fourth Canadian edition. Nelson Education Ltd.

Kingsley, J. D. (1944). Representative Bureaucracy. Yellow Springs, Ohio: Antioch Press.

Kinsley, R. P. (2016). Inclusion in museums: A matter of social justice. Museum Management and Curatorship, 31(5), 474–490.

Kottasz, R. (2015). Understanding the cultural consumption of a new wave of immigrants: the case of the South Korean community in South West London. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 20(2), 100–121.

Kraehe, A. M., & Acuff, J. B. (2013). Theoretical considerations for art education research with and about “underserved populations.” Studies in Art Education, 54(4), 294–309.

Krislov, S. (1974). Representative Bureaucracy. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Levine Museum of the New South (2017). Retrieved from http://www.museumofthenewsouth.org/exhibits/know-justice-know-peace

McCarthy, K. F., Ondaatje, E. H., Zakaras, L., & Brooks, A. (2001). Gifts of the muse: Reframing the debate about the benefits of the arts. Rand Corporation.

Mosher, F. C. (1968). Democracy and the public service. New York: Oxford University Press.

National Endowment for the Arts (2015). A decade of art engagement: Findings from the survey of public participation in the arts 2002–2012. Retrieved from https://www.arts.gov/publications/decade-arts-engagement-findings-survey-public-participation-arts-2002-2012

National Endowment for the Arts (2019). U.S patterns of arts participation: A full report from the 2017 survey of public participation in the arts. Retrieved from https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/US_Patterns_of_Arts_ParticipationRevised.pdf

NEA Office of Research & Analysis (2015). When going gets tough: Barriers and motivations affecting arts attendance. Retrieved from https://www.arts.gov/publications/when-going-gets-tough-barriers-and-motivations-affecting-arts-attendance

Onyx, J., Darcy, S., Grabowski, S., Green, J., & Maxwell, H. (2018). Researching the social impact of arts and disability: Applying a new empirical tool and method. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 29(3), 574–589.

Ostrower, F. (2008). Multiple motives, multiple experiences: The diversity of cultural participation. In S. J. Tepper & B. Ivey (Eds.), Engaging art: The next great transformation of America’s cultural life (pp. 17–47). New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group.

Ostrower, F. (2020). Trustees of culture: Power, wealth, and status on elite arts boards. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Phillip, S. F. (1993). Racial Differences in the perceived attractiveness of tourism destinations, interest and cultural resources. Journal of Leisure Research, 25(3), 290–304.

Piatak, J. S. (2016). Time is on my side: A framework to examine when unemployed individuals volunteer. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 45(6), 1169–1190.

Piatak, J., Dietz, N., & McKeever, B. (2019). Bridging or deepening the digital divide: Influence of household internet access on formal and informal volunteering. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 48(2S), 123S-150S.

Reeves, A. (2015). Neither class nor status: Arts participation and the social strata. Sociology, 49(4), 624–642.

Rentschler, R., Radbourne, J., Carr, R., & Rickard, J. (2002). Relationship marketing, audience retention and performing arts organisation viability. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 7(2), 118–130.

Riccucci, N. M., & Van Ryzin, G. G. (2017). Representative bureaucracy: A lever to enhance social equity, coproduction, and democracy. Public Administration Review, 77(1), 21–30.

Sandell, R., & Nightingale, E. (Eds.). (2012). Museums, equality, and social justice. New York, NY: Routledge.

Schonfel, R., Westermann M., & Sweeney L. (2019). The Andrew W. Mellow Foundation: Art museum staff demographic survey 2018. Retrieved from https://mellon.org/resources/news/articles/case-studies-museum-diversity/

SSelden, S. C. (1997). The promise of representative bureaucracy: Diversity and responsiveness in a government agency. Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe.

Simmons, J. E. (2016). Museums: A history. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Smith, Tom W., Hout, Michael, and Marsden, Peter V. General Social Survey with Arts Module, United States. (2016). Inter-university consortium for political and social research [distributor], 2020–07–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR37701.v1

Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center (2020). Culture Lab. Retrieved from https://smithsonianapa.org/culturelab/

Solebello, N., Tschirhart, M., & Leiter, J. (2016). The paradox of inclusion and exclusion in membership associations. Human Relations, 69(2), 439–460.

Stein, J., Garibay, C., & Wilson, K. (2008). Engaging immigrant audiences in museums. Museums and Social Issues, 3(2), 179–196.

Sweet, S., & Grace-Martin. (2012). A data analysis with SPSS: A first course in applied statistics. Boston, MA: Pearson Education Inc.

Tepper, S. J., & Gao, Y. (2008). Engaging art: What counts? In S. J. Tepper & B. Ivey (Eds.), Engaging art: The next great transformation of America’s cultural life (pp. 17–47). New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group.

U.S. Census Bureau (2010). Population distribution and change: 2000 to 2010. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-01.pdf

Weisinger, J. Y., Borges-Méndez, R., & Milofsky, C. (2016). Diversity in the nonprofit and voluntary sector. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly., 45, 3–27.

Werner, B. L., Hayward, J., & Larouche, C. (2014). Measuring and understanding diversity is not so simple: How characteristics of personal identity can improve museum audience studies. Visitors Studies, 17(2), 191–206.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Alexandra Olivares works at an art museum.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Olivares, A., Piatak, J. Exhibiting Inclusion: An Examination of Race, Ethnicity, and Museum Participation. Voluntas 33, 121–133 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-021-00322-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-021-00322-0