Abstract

First under the Millennium Development Goals and now under the Sustainable Development Goals, partnerships for development, especially between state and NGOs, remain a valued goal. Partnerships are argued to improve provision of basic social services to the poor: the state is viewed as providing scale, with NGOs ensuring good governance. Close study of three leading partnership arrangements in Pakistan (privatization of basic health units, an ‘adopt a school’ program, and low-cost sanitation) shows how state–NGO collaborations can indeed improve service delivery; however, few of these collaborations are capable of evolving into embedded partnerships that can bring about positive changes in government working practices on a sustainable basis. In most cases, public servants tolerate, rather than welcome, NGO interventions, due to political or donor pressure. Embedded partnerships require ideal-type commitment on the part of the NGO leadership, which most donor-funded NGOs fail to demonstrate. For effective planning, it is important to differentiate the benefits and limitations of routine co-production arrangements from those of embedded partnerships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Developing state–NGO partnerships to ensure delivery of basic social services to all in the developing world is integral to contemporary development thinking. Partnerships for development are one of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), now absorbed into the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This emphasis on partnership stems from its conceptual appeal as well as from everyday evidence. Promoting partnerships helps to steer the development discourse away from more rigid and narrowly defined pro-market or pro-state solutions, thereby allowing the adoption of a moderate course that can win support across the ideological divide. At the same time, in terms of actual evidence, most often it is not the state or the non-state actors alone, but a hybrid set of arrangements involving both parties through which social services are delivered (Joshi and Moore 2004). The growing emphasis in development discourse on forming partnerships as a way to meet basic development goals can be traced from the 1990s. To date, however, we struggle to find examples where donor efforts have been able to cultivate embedded partnerships between state and non-state actors to improve provision of basic social services to the poor on a sustainable basis (Teamey 2007). Despite growing studies of co-production arrangements under the rubric of synergy, co-production, collaboration, and partnerships (Brinkerhoff 2002; Coston 1998), we still know little about what factors enable NGOs and the state to turn a routine co-production arrangement into an embedded partnership for effective social-service delivery for the poor.

Based on a study of three leading partnership arrangements for delivery of basic social services in Pakistan, this article contends that in developing countries such as Pakistan, where state bureaucracies often suffer from weak governance capacity or pervasive corruption, whether or not an embedded partnership can emerge between state and NGOs is heavily contingent on the attributes of the NGO leadership. Government servants remain largely resistant to NGO interventions and tolerate them mainly under political pressure or due to personal benefits embedded in those projects.Footnote 1 Such forced or opportunistic co-production arrangements, however, fail to yield permanent solutions. Embedded partnerships, whereby the two sides develop sustainable working relations, in such contexts are highly contingent on the attributes of the NGO leadership. To make government officials change their work practices, it is important for NGO leaders to show ideal-type commitment, whereby ideational as opposed to material incentives shape its actions. Evidence of a lack of material motives helps to establish the moral authority of the NGO leadership; equally importantly, only a non-materially motivated NGO leadership can demonstrate the long-term commitment required to effectively mobilize the community and identify low-cost solutions.

Comparing three cases from Pakistan, this article demonstrates that the NGO leadership that is able to develop an embedded partnership with the government is one most cautious about engaging with donor money and most resistant to adopting the culture of professionalism and material comfort that is popular with donor-funded NGOs (Bano 2008b; Banks et al. 2015; Hulme and Edwards 1997). Donors’ ability to promote partnerships under the good-governance agenda is thus highly questionable. However, as we will see, donor-supported co-production arrangements often do lead to a successful transfer of technical expertise from NGOs to the government sector. It is possible to justify donors’ support for cultivating partnerships on this basis, but it is important to acknowledge that such knowledge transfer can qualify only as co-production, not as an embedded partnership capable of introducing good governance.

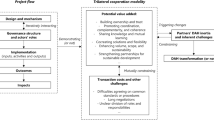

The article is divided into five sections. “Why Co-produce? Evolution of the Development Discourse” section reviews the contemporary debates on importance of state–NGO partnerships in social-service delivery in developing countries. “Background and Methodology” section explains how the three specific examples of partnership analyzed in this article were selected and outlines the research methodology. It also explains why Pakistan constitutes a particularly good case for the study of donors’ ability to cultivate such partnerships without compromising the generalizability of the findings. “Three Apparent Successes But Only One Embedded Partnership” section shares initial results to show that, while all three cases were selected because they were identified as being successful cases of co-production, in reality only one presented a case of embedded partnership where there is long-term cooperation between the relevant government agency, the NGO, and the community at all stages, where the relationship is on-going, with mutual respect, and where it is effective in delivering a critical social service which would not have been possible without that partnership. “Analysis: Factors Shaping the Partnerships” section compares the three cases to identify the main factors shaping the partnerships. The section demonstrates how attributes of the NGO involved hold the key to determining whether or not an attempt at co-production will flourish and turn into an embedded partnership. “Conclusion” section presents the conclusions.

Why Co-produce? Evolution of the Development Discourse

Starting from the early 1980s, the growing concerns with state-led models of development created arguments in favor of NGOs’ involvement in the delivery of basic social services within the discourse and practice of leading international development agencies. Governments in the developing world were not only often found to be corrupt, inefficient, and top–down; they were increasingly also seen to be uncommitted or incapable of providing basic services to all (Hulme and Edwards 1997; Joshi and Moore 2004). Involving NGOs in social-service delivery was thus argued to be a good solution: compared with the private sector, NGOs were viewed as driven by ideals instead of profit-related concerns; they were also expected to be participatory, democratic, bottom–up, and consequently effective in developing innovative localized approaches to development (Bano 2012; Hulme and Edwards 1997). This push toward combining state and NGO efforts to improve service delivery was thus also closely tied to the good-governance agenda; NGO involvement was believed to enhance the participation of common citizens in the planning, implementation, and monitoring of state-run social-service delivery projects (Brinkerhoff 2002, 2003).

This focus on good governance through enhanced community participation has led to certain assumptions about the ideal type of state–NGO partnership, whereby its main benefit is viewed as its ability to introduce good practices within the government agencies through cultivating respect, mutual trust, and consultative planning (Fowler 2000; Teamey 2007). One of the studies informing the debate on partnerships was Judith Tendler’s (1998) Good Government in the Tropics, which questioned dominant assumptions about poor state performance in developing countries by looking at innovative state-government reforms in Brazil, which dramatically improved public-sector performance. Among other things she highlighted the importance of state and civil-society engagement in improving service delivery. Peter Evans similarly highlighted the role of synergy and embeddedness of state institutions in improving service delivery (Evans 1996a, b). Although of the view that partnerships can best flourish in contexts characterized by egalitarian social structures and robust, coherent state bureaucracies, Evans argued that synergy is constructible even in comparatively more adverse circumstances typical of Third World countries (Evans 1996a, b). Both Tendler (1998) and Evans (1996b) showed that norms of cooperation and networks of civic engagement can be promoted within public agencies and used for developmental ends through greater community participation. Elinor Ostrom (1996) also lent weight to this debate by focusing on studies of co-production arrangements whereby the ‘Great Divide’ between pro-market and pro-state positions was effectively bridged to produce public goods. Referring to co-production as the process through which inputs used to produce a good or service are contributed by individuals who are not in the same organization, Ostrom (1996) argued that citizen involvement can play an active role in producing public goods and services of consequence to them.

These critical studies mapping the importance of state–civil society collaboration in the delivery of basic services to ordinary members of the public, which were published under the rubric of co-production, synergy, partnerships, or good governance, also influenced thinking within development institutions. Coston (1998) notes how major donors, including the World Bank, during this period encouraged collaboration between governments and NGOs to improve policy and social-service delivery. Brinkerhoff (2002, 2003) similarly notes how policy documents by major development programs such as USAID’s New Partnership Initiative, the UN Common Country Framework, and the World Bank’s Comprehensive Development Framework and Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers placed explicit emphasis on the need for governments to consult and encourage the participation of civil society as well as the private sector. It was the growing consensus within the development agencies that the state alone cannot deliver and neither can NGOs that resulted in the inclusion of support for development partnerships as a key Millennium Development Goal (Brinkerhoff 2002).

However, despite this increased emphasis, evidence of embedded partnerships capable of producing good governance remains limited (Brinkerhoff 2002). We still struggle to find examples of successful partnerships, especially those engineered through development funds, which can yield the kind of community mobilization and tripartite engagement between the state, NGOs, and the community that is emphasized by the above studies. Ideal-type partnerships are viewed as embedded within the community and are argued to introduce good governance through increased accountability, enhanced state–society involvement, and low-cost innovation (Teamey 2007). Instead of partnerships, most cases of donor-supported co-production on the ground demonstrate contractualism, with limited evidence of trust or mutual consultation; in many contexts, the relationship between state and civil society actually remains hostile (Teamey 2007).

Given the evidence in the above studies that community-embedded partnerships can improve service delivery, the question is why are international development agencies often unable to cultivate effective state–NGO partnerships? This article addresses this question with evidence from Pakistan.

Background and Methodology

Since 2001, Pakistan has benefitted from increased aid flows. The need to make Pakistan an active partner in the US-led ‘war on terror’ led to a major influx of development aid between 2001 and 2010.Footnote 2 Much of the aid channeled to the social sector during this period was closely tied to support for a devolution program introduced by General Musharraf (President of Pakistan 1999–2008). Pakistan’s performance on basic indicators across the three core social sectors, education, health, and sanitation, has remained dismal (MHHDC 2016); the Social Action Programme (SAP), a multi-donor program implemented during the 1980 s and 1990s, recorded little improvement in core indicators, while the final evaluations noted institutionalized corruption within the state system (Ismail 1999). In a political context where Western governments were keen to win leverage with the Pakistani government for global security concerns, supporting major investments in the country’s social sector through efforts at decentralization and promotion of a good-governance agenda was viewed as an effective strategy.

For the government of General Musharraf, who prior to the events of September 11, 2001 was unpopular within the international community for ousting an elected government, rolling out a devolution program that increased the power of district governments over the provinces was expedient; it helped to establish its pro-people credentials while arguably weakening the power of provinces vis-à-vis the federal government.Footnote 3 In the policy documents of the major donors operating in Pakistan in the early 2000s, the support for devolution came hand in hand with an emphasis on partnerships (Bano 2008a). Again this demand suited General Musharraf’s political legitimization agenda; he had already appointed many NGO leaders to senior government positions, to demonstrate that he was cleansing the system of ‘corrupt politicians’.Footnote 4 Given this emphasis on state–NGO partnerships by donors as well as by the government between 2000 and 2008,Footnote 5 Pakistan thus presents a good case for a review of the effectiveness of donor-led efforts in promoting good-governance practices through such partnership arrangements. However, the heightened interest of the state and donors in supporting partnerships in the context under study does not restrict the generalizability of the findings. Rather, the challenges faced by these best-performing cases in an apparently supportive environment can only be more severe in less supportive contexts. Thus, the lessons drawn from a study of these three partnership arrangements in Pakistan remain useful for other contexts, as the same models are being trialled in other contexts.

This article draws on in-depth study of three prominent state–NGO partnership arrangements from the three key social sectors: health, education, and water and sanitation provision. This cross-sector selection was deliberate; it made it possible to assess whether sector-specific factors could shape the success of the partnership. The initial fieldwork was conducted between 2006 and 2008. This was followed by another round of fieldwork in 2016, to assess how the partnership arrangements analyzed had fared in the long term. Each of the three cases selected was identified as being the best case of partnership within that sector, as viewed by dominant actors within the field. At the initial stage, extensive interviews were conducted with officials within the relevant state agencies at all three tiers of government (federal, provincial, and district), with representatives from leading NGOs working within that sector, and with the sector specialists within key development agencies. These initial sector-wide mapping interviews helped to map the various partnership arrangements that were in place within each sector.

Interviews and review of policy plans and documents produced by the donor agencies, NGOs, and the relevant ministries and departments showed that within the health sector tuberculosis-prevention programs, HIV/AIDS-prevention programs, and the privatization of basic health units (BHUs) were the three prominent programs under which state–NGO partnerships were being promoted. In the education sector, the two most popular state–NGO collaborative arrangements were an ‘adopt a school’ program, whereby government schools are adopted by NGOs to improve both the physical infrastructure and quality of teaching, and non-formal school programs run by NGOs with resources made available by the state. Within the water and sanitation sector, low-cost sanitation programs that provide access to basic sanitation facilities in poor communities and katchi abaddis (informal settlements) were the key area of state–NGO partnership (Hasan 1999, 2000).

Since the research aimed to understand the factors that lead to effective state–NGO partnerships, further interviews were conducted to identify which one of these diverse partnership arrangements within each sector was considered by all the major players to be the most successful. Within the health sector, the privatization of basic health units to the Punjab Rural Support Programme (PRSP) was identified by most as being the most prominent case of partnership. It presented a more complex case of co-production, as here the public-health facilities were being handed over to the private sector to improve service delivery; the tuberculosis and HIV programs, on the other hand, were mainly government-run, with NGOs being contracted to implement specific activities. Within the education sector, a number of NGOs were working with the state on both the ‘adopt a school’ program and non-formal school programs. ITA, Idara-e-Taleem-o-Aagahi (Center for Knowledge and Consciousness), the NGO selected from within the education sector, combined both these programs, actively lobbied the government on policy matters, and also acted as a service provider to the government by offering training programs for government teachers and education-management staff. Within sanitation, Orangi Pilot Programme (OPP) operating out of Karachi, which is internationally known for its low-cost sanitation programs, made an obvious choice.

During 2006–2008, prolonged fieldwork was conducted with all three cases. In 2016, fresh fieldwork was conducted to assess the long-term sustainability of each of the three partnership models. The initial fieldwork involved detailed open-ended interviews with NGO leaders and senior management at the head-office level, followed by in-depth fieldwork at selected sites where the partnership program was being implemented. In the case of OPP, this involved fieldwork within Orangi Town in Karachi and in Lodhran district in Punjab, where a local organization had replicated Orangi’s low-cost sanitation scheme; in the case of PRSP’s take-over of basic health units, the focus districts were Faisalabad, where the program was known to have shown dramatic improvement in working of the BHUs, and Lodhran, the first district in which the program was launched. For the education case study, primary fieldwork was conducted in Sheikhupura district, where the NGO studied was working with the government at multiple levels through a major donor-funded program.

During the fieldwork, time was spent at the actual site of service delivery to observe the quality of the services provided, to have open-ended discussions with the staff and managers of the field offices, and to interview the users of those services. Interviews were also conducted with all the relevant officials at all tiers of the government, which mainly included officials within the district and provincial governments. Since the water and sanitation sector is managed through the city government rather than via a ministry, the relevant government officials were based mainly within the Karachi Water and Sanitation Board. Group discussions were also held with community members to assess the extent and nature of community participation. During the follow-up fieldwork in 2016, selected interviews were conducted with actors from each one of the three partnerships to help trace their evolution over time.

Three Apparent Successes But Only One Embedded Partnership

ITA, the NGO selected within the education sector, had its head office in Lahore, the capital of Punjab, the most populated and politically influential province in Pakistan. Established in 2000, this NGO has from its very inception had an explicit focus on working in partnership with the government by adopting government schools, running non-formal school programs out of government school buildings, providing policy advice, and offering training for government teachers and education managers. Under its ‘adopt a school’ program, the NGO raises financial contributions from the corporate sector, while the government reciprocates by allowing it access to the government schools and granting permission to train the government school teachers and use the government school buildings for running its non-formal school program. Much of this interaction is at the district level.

Between 2006 and 2008, ITA was involved with a number of donor-funded projects in Kasur and Sheikhupura districts, where it partnered with another NGO to reduce school drop-out by improving government school facilities and increasing literacy through non-formal schools. Field visits to the schools supported by ITA showed visible improvements in teachers’ attendance, the quality of teaching, school infrastructure, and parental satisfaction. During school visits, it was easy to see that the NGO staff members had good access to the adopted government schools and were in regular contact with school principals and teachers regarding teacher and school-management training and in-school mentoring programs. The school physical infrastructure was visibly improved through the provision of proper desks and chairs, decent toilets, and playground facilities. In a context where government schools are often reported as having high teacher absenteeism and a focus on rote learning (MHHDC 2016), the adopted schools demonstrated good teaching standards where teachers used child-centered learning methods. The parents interviewed from within the community also reported high levels of satisfaction. In terms of improving service delivery, the partnership appeared effective.

The health-sector case which focused on the privatization of BHUs in selected districts also involved working with the government staff and facilities, but using a different model. Here, the entire government budget for running the BHUs was handed over to the partner NGO, PRSP. The model was seen to be particularly desirable because under it the government continued to shoulder the financial cost of running the BHUs but transferred the government annual budget for those BHUs to the NGO and also gave it complete freedom to utilize the budget as it deemed fit. The government-allocated budget covered the salaries of all the staff at the BHUs and paid for medicines and all other running costs. The only financial cost borne by the NGO was the salaries of the management staff; it employed five or six employees in each district to manage the program. Studies available at the time of the fieldwork (World Bank 2006a), as well as independent fieldwork conducted in the two districts (Faisalabad and Lodhran) where the program has been implemented, showed that PRSP was able to record dramatic improvements in performance: the problem of staff absenteeism disappeared, patient turnout improved, government-supplied medicines which in the past always seemed to be out of stock were now available, and all these improvements were recorded within the existing budget. International evaluations and research studies continue to note BHU privatization in Pakistan as a successful case of public–private partnership within the health sector for improved social-service delivery to the poor (Hatcher et al. 2014).

OPP-RTI, the low-cost sanitation program included in this study, is one of the three organizations operating under Orangi Pilot Project (OPP), an NGO established in the early 1980s by a renowned development practitioner, the late Dr. Akhtar Hameed Khan. An ex-bureaucrat, he earned early recognition for his work at Comilla Pilot Project in Bangladesh, although it was under OPP that he took his ideas to full maturation (Khan 1998). On the government side, the key actors in this partnership are the Karachi city government and the Karachi Water and Sanitation Board. OPP takes responsibility for mapping the areas in need of sanitation facilities, developing low-cost sanitation solutions in collaboration with the government field staff and engineers, and mobilizing the communities to invest their share of the financial and labor contributions. The government, on the other hand, is required to take responsibility for the major infrastructure development, including building the big sewers and covering the nalas (drainage channels).

The government and the community are expected to share the financial costs, while OPP provides free technical expertise. Through the program, 1,45,466 households have invested US$3.2 million in the provision of in-house latrines and external sewers, with the government investing more than US$4.6 million in trunk mains. OPP is a member of the Karachi city government focal group for the development of drainage channels in Karachi, and over time it has also convinced the Karachi Water and Sanitation Board, which for a long time was a strong supporter of mega projects funded through foreign loans, to consider instead low-cost alternatives provided by OPP. In 1992, the Karachi Metropolitan Corporation accepted the OPP model for its sewerage project, financed by the Asian Development Bank (ADB), for a part of Orangi township in preference to a much more costly model being advocated by the ADB technical advisers. In 1994, Sindh Katchi Abadi Authority, the provincial government agency responsible for the provision of land titles and upgrading of Katchi Abadis (slum settlements), adopted the OPP approach. In 2003, the Punjab Katchi Abadi and Urban Improvement Directorate also accepted the model. OPP-RTI is now the Karachi City Government’s team member for developing the city’s main sewage disposal and drainage channels; and the model has been replicated in other parts of Pakistan (World Bank 2006b).

These three cases of state–NGO partnership were selected because the government officials, NGOs, and donors interviewed had identified the selected model as the most successful example of partnership within that sector. The fieldwork conducted at the site of delivery of those services had confirmed that these perceptions were correct: collaboration between the state agencies and the relevant NGO had indeed improved service delivery. Yet the fieldwork also revealed that the three cases had very different operating principles guiding these partnerships, and these differences had major consequences for the kind of relationship formed between the two sides, the level of trust enjoyed, and the extent to which NGOs were able to influence government working practices in the long term, instead of merely providing temporary fixes. Only OPP met the idealized partnership standards characterized by mutual trust, true community engagement, and long-term change in government operating practices.

During the fieldwork, government officials repeatedly recognized the contributions made by OPP to their planning and implementation activities. Noting that OPP is very good at mapping the drainage systems and preparing cost estimates, one of the government officials explained how he had recently prepared a PC1 (the term used for government projects) worth Rs. 11 million for work on nine major natural-water flows within Karachi, with support from the OPP senior management and the field team. In his words: ‘It is because of OPP’s efforts that 30 per cent of nalas (natural-water flows) in Karachi have been covered. OPP’s strength is that it is very strongly rooted within the community so it knows the area much better than the government. It is therefore very useful to work with them.’ He further noted that he would like OPP to work also on improving the road networks and clean drinking-water supply within these slum settlements.

Compared with OPP, the other two cases were able only to provide technical solutions, which did improve provision of services but without bringing about any systematic change in the working of the relevant government agencies. Consequently, the improvement in service delivery in these two cases was only temporary, with no evidence of long-term sustainability. ITA did manage to get special access to government facilities to ensure that it delivers specific education projects; but it failed to show any systematic long-term impact of its collaboration in terms of changes in government working practices. In 2008, its two major donor-funded projects involving the government in the two districts of Kasur and Sheikupura were drawing to a close. There was little evidence of the government absorbing the program activities. Further, many of the government officials at district level were critical of ITA activities; they argued that ITA forced them to engage in activities by using their connections among senior government officials or among donor agencies. In 2016, ITA was still working on similar kinds of project, but in different locations than were covered in 2008, and its operating principles were unchanged; reliant on donor funds to implement large projects, as in the case of most NGOs in Pakistan (Bano 2008b), its focus changes from region to region, depending on the funding it can secure.

PRSP similarly has had little influence on the government’s standard operating practices regarding running the BHUs. Despite providing ample evidence of improvement in service delivery at the BHUs, PRSP has failed to win over the health bureaucracy. The latter has actively resisted the program from its very inception, and in 2008, the Chief Minister of Punjab actually announced that PRSP was to return the management of the BHUs back to the Ministry of Health. The follow-up fieldwork in 2016 revealed that due to the change of government after the 2008 elections, PRSP was able to get an extension of the BHU management contracts. However, the replication of the model to other districts has been very slow, and to date, the health bureaucracy is resisting formal adoption of this model. If the PRSP does not secure another round of extension on its current 3-year contracts, the BHUs will revert to the health ministry.

What then explains the differing abilities of these three apparently successful state–NGO collaborative arrangements to turn into embedded partnerships whereby they can trigger actual change in government operating practices to ensure long-term change?

Analysis: Factors Shaping the Partnerships

Close study of the three cases and their evolution over time shows that the stated rationale of the partnership in all three cases was technical expertise. All three partnership arrangements were premised on an assumption that the partnering NGO could offer technical expertise that could help to improve the delivery of basic services by the state agencies. However, whether the state bureaucracy accepted the partnership and adjusted its working practices accordingly was shaped by the level of trust that the NGO leadership and personnel developed with the state actors, as well as with the community. This section identifies seven factors that helped to shape this mutual trust. However, it also shows that out of these seven variables, the core explanatory variable influencing all others is the motivation of the NGO leadership. The success of OPP compared with the other two cases shows that ideational commitment on the part of the NGO leadership is core to building an embedded partnership. Donor-funded NGOs, due to being bound by project deadlines, are inherently incapable of demonstrating that ideational commitment, therefore severely restricting their ability to form embedded partnerships that could introduce good-governance practices within state bureaucracy.

Technical Expertise

In all three cases, interviews and observation show that the basic appeal of the partnership to the government rested in the NGO’s ability to offer technical expertise and solutions that could help to improve the delivery of the given service. In the case of OPP, this technical expertise involved the skills to draw detailed maps, develop budgets, and help the government identify construction patterns that could reduce the total cost. As one OPP senior official explains: ‘When I joined OPP in 1982 we spent so much of our initial time just mapping the area. Once the map was ready it helped the community as well as the government visually see the problem, and our solutions seemed much more realistic to them then.’ Fieldwork with the Lodhran Pilot Project, which had replicated the Orangi low-cost sanitation model (World Bank 2006b), showed that detailed mapping had been equally critical for it to win the cooperation of the municipal authority. Government officials in both the contexts noted how in their offices they lacked the technical expertise to develop these detailed maps, and keep them updated and readily available. With the map in front of them, it was argued, everyone can see the problem and its roots.

Another important feature of the technical support offered by OPP is that its proposed solutions were low-cost. OPP was able to change the government strategy of creating extra depth for the sewers, which reduced costs. As one OPP member noted, ‘The estimates get easily approved when they are low-cost.’ Low costs also help to mobilize the community. In the words of an OPP field mobilizer, ‘When we mobilize the people, the most effective tool is to highlight the low cost of the project as compared to the benefits they will get.’ The OPP field staff brief the community members about how the small investments required of them to build the sanitation facilities will save them the extra medical costs.

In the case of PRSP, the technical expertise took the form of managerial practices: how to design a management and monitoring system that will yield improved service? In the case of ITA, the technical expertise revolved around teacher and school-management training, and fund raising to improve school infrastructure facilities. It was these specialized skills that helped to create a justification for the start of a partnership dialogue with the government. In all three cases, the NGO initiated the dialogue, and what it offered to the government was its technical expertise.

Informality of the Contract

While technical expertise provided the foundation of the partnership, the three cases show that the actual working arrangement can take on different modes of formality, ranging from the signing of formal contracts to working under informal agreements. In the case of PRSP, the partnership is based from the beginning on a formal contract. However, the contract is not a very specialized document, or very stringent in laying down the do’s and don’t’s. ITA similarly opts for formal contracts; in fact, it goes a step further and develops a detailed Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the relevant government authorities. It takes pride in the fact that it was the first NGO to initiate the preparation of such MoUs, and that it has built the capacity of the district government to develop partnerships with NGOs through drafting these agreements.

The OPP, on the other hand, has a very different way of negotiating access. It does not maintain any formal contract with the government; formal contracts, it maintains, often bind organizations to specific targets and take away the flexibility to adapt to changing requirements, so that in the end meeting the contract targets becomes more important than addressing the actual objectives. In the beginning, it had some formal tripartite agreements with UNICEF and the government, but later it decided that such agreements do not work. As an OPP senior official explained, ‘MoU is only needed when the government is giving us money. We feel that just taking money does not build a partnership. There are many aspects of each work, and it is not possible to include them all in an MoU. Not having a formal agreement is much more powerful. It gives us more room to negotiate and to establish trust.’

When OPP entered into formal agreements, its management found that they became bound to delivering certain things which eventually were not important, and this disrupted their progress on the ground. OPP thus believes in building relationships with officials at different layers within the government offices concerned, rather than just the top official. This has been critical, as people in the lower government ranks are the ones who implement the policies. Working across the different tiers of government also gave the relationship long-term durability; many of the government officials whom OPP initially began engaging with when they were junior officers are now in senior positions. This has helped to ensure that changes in the appointment of government officials do not make a difference to its relationship with that government department.

Politicians Versus Bureaucrats

The three cases also show that political and bureaucratic elites have different incentive structures, whereby politicians are more likely to endorse such partnerships than the bureaucrats who actually control the resources that are to be shared. Elected representatives have a stronger incentive to support some of these partnerships, as long as they can claim credit for any success among their constituencies; the bureaucrats, in most cases, lack such incentives. In the case of PRSP, the project has survived to date despite active resistance from the bureaucracy, due to the continued backing of political leaders, which was partly due to chance. The Chief Minister, who had initially approved this model on the recommendation of one of his advisers, had lost support for it by 2008, when that adviser himself became a federal minister and a political rival. However, the 2008 elections led to a change of political government in Punjab, bringing back to power the Chief Minister who had actually established PRSP, a government-owned NGO. This change of government was critical to enabling PRSP to retain control over the BHUs in selected districts. The bureaucracy, which lost control over the BHUs’ budget, has, however, shown steady resistance to this model, thereby hindering its formal adoption by the ministry.

For ITA, the experience was similar. While the Chief Executive, due to her close links with the sitting government, was able to gain permission to access the government facilities and demand the cooperation of government employees, the ability of ITA to mobilize the district-level government officials in charge of day-to-day activities remains limited. This shows that the political and bureaucratic elites have different considerations when reviewing these partnerships. Since it is often the bureaucrats who lose direct control over resources as a result of partnership arrangements, and since, unlike the politicians, they are often unable to claim personal credit for any success of the project in question, they remain more critical of such partnership arrangements; this was evident in all three cases. This does not imply that politicians are more sincere about improving social-service delivery, as they often approve inefficient projects in order to gain political mileage or in the hope of obtaining financial bribes. But this does show that winning the support of the bureaucrats and administrative staff responsible for delivery of the services is key to embedding the partnership. In the case of OPP, what has enabled it to actually change government operating principles vis-à-vis developing sanitation projects for slum areas is its success in winning the trust of the government bureaucrats responsible for sanitation planning. As we will see below, however, winning this trust demands a level of commitment that most donor-funded NGOs are unable to demonstrate.

Access to Government Networks

The three-case comparison also shows that another feature common to the three models was the ability of the NGOs to form links with the government and have knowledge of its working. This link was the strongest in the case of PRSP. PRSP is actually a government-owned NGO and is managed by ex-bureaucrats with years of experience in government service. It is modeled on the Aga Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP) that was launched in the northern areas of Pakistan and the Chitral area in 1982 by the Aga Khan Foundation. Over time, the model won much acclaim for mobilizing the rural communities to implement important social and economic development projects leading to its replication by the federal as well as provincial governments. The PRSP was launched in 1997. These Rural Support Programmes (RSPs) operate as semi-autonomous bodies whereby the senior management comes from ex-government officials, but the organization does not have to follow the standard government operating procedures; the RSPs thus benefit from greater flexibility than the regular government departments. The PRSP senior management thus had first-hand knowledge of government working and had strong connections within the bureaucracy. Further, it ensured that all the managers whom it recruited to supervise the BHUs’ management at the district level were actually current government officials who were willing to operate on a 3-year secondment. These extensive social networks within the bureaucracy and the first-hand knowledge of how government operates are key to ensuring the survival of this model to date. The ITA case similarly shows how strong social networks allowing access to senior politicians and bureaucrats are critical to the formation of state and NGO collaborations. The head of ITA had acted as an adviser to the federal minister for education in the early years of the present century and was also widely respected within the international development agencies. She thus had first-hand knowledge of government working practices and extensive social networks within the government and the donor community.

This feature was also shared by OPP. Its founder, Akhtar Hameed Khan, was a highly respected ex-bureaucrat who enjoyed great esteem within government agencies (Hasan 1999, 2000). However, unlike the other two cases, he had a very different approach to using these connections. As noted by an OPP staff member, his approach was based on a conviction that resistance from the government side is often not financial but psychological in origin. It is therefore important to engage with the government officials in a very tolerant manner. He maintained that the focus has to be on changing their attitude and winning them over by presenting them with evidence, rather than pressuring them to cooperate through using connections at high levels. Whereas PRSP and ITA both use their social networks among senior politicians or bureaucrats to pressure relevant government authorities to cooperate with them, OPP emphasized winning the trust of officials at all tiers of government but convincing them through perseverance and constant follow-up.

Community Participation

As outlined in the literature review section, existing studies place heavy emphasis on community participation in order to ensure the success of these partnerships (Teamey 2007). The three-case comparison supports this assertion. There is a clear difference in the level of community embeddedness of the three cases. All three in principle ascribe importance to community participation, but only OPP practices it as idealized in the literature. The OPP model is characterized by a strong sense of confidence in the ability of the community to address its own needs. It maintains that the community, which has to live with the given problem, is capable of finding solutions to it if provided with a basic level of technical support. Its sanitation model is therefore based on cost-sharing, where the community provides labor to build small lanes, while the government bears the cost of linking the small lanes to the main drainage system. As the late Dr. Khan notes in his book (Khan 1998), his emphasis on community participation was shaped by the realization that in Orangi the majority of the houses had been built without any support from the Karachi Development Authority or the House Building Corporation, and such was the case for most other facilities, including schools, health clinics, and micro-enterprises. He therefore worked with the community to find solutions to sanitation problems too.

Fieldwork revealed the deep embeddedness of OPP within the community. The OPP office is physically based within the Orangi area, and all the OPP field staff are recruited from within the community, as they know the local area well. The salaries are not high; the emphasis is on motivating the staff by ‘behavioral culture’ based on respect and recognition, rather than ‘material incentives.’ As one of the senior leaders at OPP noted, the ‘humanness of relationship’ is very important to them. She further noted, ‘Dr. Sahib used to order a lot but no one used to listen. In our relationship there was a lot of love, so we could fight with each other.’ Interviews with the field staff placed similar emphasis on the motivating power of such human interactions. Another field team member noted, ‘I live in Orangi because of the relationship with the community, I’m glued to OPP. I’ve freedom here, this is the motivation.’ Another staff member in the computer department noted, ‘I came here as a student. I got a chance in a multi-national company, where I worked for 2 years on Geographic Information System (GIS). It was a 2-year work contract. When it ended they offered me extension. I refused and re-joined the OPP.’ This approach to recruiting staff from within the community comes with a strong emphasis on a mentoring role for the senior leadership.

In the case of ITA, on the other hand, the community was involved only nominally, mainly through seeking feedback from the parents about changes introduced in the adopted government schools. In fact, the head of ITA was critical of the heavy emphasis placed on community involvement and argued that not every development intervention can necessarily benefit from it. The same was the case for PRSP. Even though PRSP as an organization has a marked focus on community mobilization, this was not the case with its BHU program. The community-participation element was largely similar to that of ITA, where the community members were involved mainly in order to get feedback. A committee of local members was formed to help to monitor the performance of the adopted BHUs, but during the fieldwork there was no evidence of the committee being an active partner in the actual planning and implementation of the model. This was unlike the OPP case, where it was clear that the OPP staff and senior management were much more embedded in the community than the government staff: a fact that the government officials also acknowledged during the interviews. Thus, the three-case comparison shows that not all NGOs are interested in mobilizing communities or are necessarily good at it; but those who do seriously invest in community mobilization are the ones that can make the partnership sustainable in the long term.

Views on Development Aid

All three cases also had different approaches to, and levels of dependence on, foreign development aid. PRSP’s take-over of BHUs was not directly funded by any donor agency, but it had strong policy backing from the World Bank (World Bank 2006a). Also, PRSP as an organization draws heavily on donor-funded projects and works with most donor agencies operating in Pakistan.Footnote 6 In the case of ITA, its founder is deeply embedded within the development sector and was appointed as an adviser to the minister, herself an NGO leader, due to her experience of having worked with development agencies on international postings. ITA had thus from its inception in 2000 been actively engaged with aid-funded projects, even though it is keen to highlight that it also mobilizes funds from the corporate sector and from Pakistanis overseas. Over the years, it has taken development assistance from all major development agencies operating in the education sector in Pakistan.Footnote 7 The OPP, on the other hand, has a very different relationship with the development agencies. It actively engages with the development community, mostly to share its learning, but it is highly resistant to becoming dependent on donor funds. It is also very selective in accepting support from any development agency. Further, it actively lobbies the government agencies against taking loans from international financial institutions (Hasan 1999, 2000). Its core funds come from a seed endowment that it received from a Pakistani bank at the time of its establishment.

Core Explanatory Factor: Motivation of the Leadership

The above differences in the working of these three organizations ultimately stem from the basic differences in the motivation of their leadership. All three are NGOs claiming to improve basic social services for poor communities, but their origins and the motives of their leaders are very different. OPP’s leaders from the beginning have been known for very humble living, low-cost offices, and low salaries. Dr. Akhter Hameed Khan is widely respected for living a very simple life despite the fact that he could have chosen a very luxurious lifestyle. As noted by an OPP staff member: ‘Akhtar Hameed Khan always said that you cannot work with the community and win their confidence if you have salaries 5–10 times higher than what they get.’ It is a well-known fact about OPP that it has never taken to the NGO culture—where offices are normally located in up-market areas, salaries are high, and four-wheel drives are considered a necessity (Bano 2012; Hulme and Edwards 1997). OPP’s leadership does not undertake donor consultancies and is very clear that material aspirations hinder the formation of a trusting relationship with the government, as well as with the community. All staff interviewed repeatedly emphasized that the organization inspires through ideological rather than material incentives and through promoting team spirit.

Many of the senior leaders who were trained by Dr. Akhtar Hameed Khan and took over after his death have strong technical expertise, as some of them were engineers who led the mapping process; but they work on salaries much lower than they can earn in the market or from consulting in the development sector. Not surprisingly, then, OPP’s leadership is rather vocal in its criticism of the commercialization of the NGO sector by donor projects. OPP does not take any money for the work it does for the government. The senior leaders feel that if they take money they will lose the power to influence the government; in the words of one member: ‘By not taking money for our services we are able to have a bigger influence on the policies, which is our main purpose.’ The government officials interviewed also noted how OPP helps them even design the Terms of Reference (ToRs) for any consultant whom they need to hire without charging any fee. The government officials interviewed took OPP’s refusal to charge fees for its services as a sign of its leadership’s commitment. These officials were keen to emphasize that the profiles of the senior leaders of the OPP (their simple living and their conscious choice to stay away from donor projects) were all signals of their commitment. Among the government officials interviewed in all the three cases, there was a widely shared concern that NGOs have become a business whereby donor money is used to pay high salaries, maintain posh offices, and host lavish conferences in five-star hotels. The fact that OPP’s leadership and organizational culture, was different and that its leadership actively resisted turning the community work into a personal profit-making exercise, was noted by all the officials interviewed within the government.

Compared with OPP, the leaders of ITA and PRSP do gain both materially and professionally from their positions. The head of ITA does not draw a salary, but leading the NGO gives her access to donor consultancies and paid advisory roles within donor and government projects. This does not necessarily show a lack of commitment on her part, but, as I found in my interviews with the district government officials, it did make the staff in the state agencies untrusting of her motives. The staff of ITA is also motivated by professional development incentives rather than by cultivating strong community ties. The employees get a good salary, a good working environment, and good training opportunities (including opportunity for foreign travel). Similar incentives motivate the PRSP’s senior management and staff. All the senior management and staff are incentivized through material and professional benefits. The BHU model was also being managed by people recruited on secondment from government for 3 years—a normal practice among government bureaucrats, who are primarily motivated to accept seconded employment for a few years by the bigger salary packages offered by development-sector programs. Some of the officials also mentioned that the project had a good reputation of doing well; this, they noted, acts as an incentive as it helps staff to progress up the career ladder if they are associated with projects that have come to be viewed as successful.

This basic difference in the motivation of the leadership of the three NGOs has a bearing on all other factors that shaped the partnerships. Since OPP’s leaders are not driven by donor funding, they do not have to move to new projects and communities when the funding comes to an end. The leadership is committed to an open-ended long-term engagement, with the view that real solutions depend on genuine collaboration between the government and the local community. Seeing its role as a facilitator, it realizes that it has to invest in long-term negotiations which are necessarily slow and difficult: only these can change the attitudes of the community as well as those of the government officials. It was also this long-term commitment that through trial and error and experience made it possible for its low-cost component-sharing model to evolve. As one of the OPP senior officials explained, ‘initially, we ourselves had no clue of how exactly should the sanitation problem be solved. It was only through involving the community and through trial and error that we developed this model, which involved contributions from the community as well as the government. It was only after 1997 that we started talking about this model in terms of component sharing.’

Also, a lot of OPP’s expansion has happened in response to community demands, rather than due to planned activities. For example, OPP has in recent years been involved in resisting evictions of people from certain areas that take place on the pretext that government needs that area for the provision of sanitation facilities. OPP became involved in this because it receives complaints from the people. OPP is now developing mechanisms to check land grabbing of prime areas on the pretext of sanitation-expansion plans. This expanding agenda of work prompts one OPP senior official to explain: ‘At the point of starting the work, we often do not know how far we might end up going. A lot of our achievements, which today are seen as phenomenal, started as simple responses to immediate community needs, which gradually evolved as we tried to address those needs.’ The formal contracts negotiated by ITA and PRSP by means of their social networks win official permissions in one go, but such top–down access does not necessarily help to change the attitudes of the government staff. OPP, on the other hand, uses a bottom–up approach to winning government trust. It is, however, important to note that being bottom–up does not imply showing no resistance to the government authorities.

As in the case of PRSP, OPP’s model also puts pressure on the resources controlled by the relevant government authorities. While OPP did not take over the budget of the relevant government agencies, it did actively mobilize the community to put pressure on the government agencies to stop taking on big loans from international financial institutions for sanitation projects. This, as noted during the interviews, did create friction with the government officials, who often make personal gains out of the grants or loans awarded by development agencies. But the key lesson from the OPP experience is that prolonged commitment and strong moral reasoning can change the attitudes of the government staff. From the early 1990s, when there was serious friction between OPP and the relevant government authorities over government plans to take an ADB loan, to early 2000 there was a major shift in the attitudes of the government officials toward development loans. In lobbying the government, OPP did not take the tensions to the public via the media, as it argues that aggressive lobbying can break down all channels of meaningful communication. Instead, it focused on mobilizing the local community-based organizations (CBOs), other donor agencies, local activists, and the media, and gave them concrete evidence that a previous sanitation program implemented by means of an ADB loan had failed. At the same time, it offered a low-cost alternative to the model being proposed under the loan. The sitting mayor of Karachi was convinced by the evidence provided and refused to go ahead with the ADB project. Thus, the OPP’s case shows that the views of government officials can be changed by effective community mobilization and demonstration of ideational commitment on the part of the NGO leaders. Table 1 helps capture how due to its strong community embeddedness and ideational commitment, OPP’s leadership was successful in cultivating an embedded partnership when the two other organizations failed even though they too offered valuable technical expertise to the partnering state agencies.

Conclusion

My follow-up fieldwork in 2016 with NGO representatives, government officials, and advisers within major development agencies reconfirms that these three state–NGO partnership arrangements remain the most prominent cases of co-production within the social sector in Pakistan. In-depth study of the three cases has shown that two of these three apparently successful cases fail to qualify as embedded partnerships. Donor-led efforts have thus had limited success in supporting embedded partnerships that can actually change the attitude of the government servants, and the government way of working, to improve the provision of social services. But this failure is not simply due to resistance from the state agencies. As the OPP case has shown, attitudes of government officials and standard operating practices within government departments can be changed, but making these deeper attitudinal changes requires long-term commitment and a high moral standing on the part of the NGOs. This is not possible unless the NGO leadership has ideational motivations.

Donor funding encourages short cuts by enabling NGOs to offer material incentives for cooperation, or encouraging them to lobby senior politicians to approve certain collaborations. This promotes a commercial culture whereby NGOs try to produce quick results by either offering government officials perks in the form of free computers, per diems for training sessions, international conference invitations, etc., or by exerting political pressure on them to cooperate. Collaborations negotiated through such political pressures, as in the case of PRSP, help the NGOs to by-pass lower-level government officials, rather than trying to engage with them and make them change their way of working. Such measures fail to change the attitudes of the government officials, thus creating a firm resistance against the program. Development organizations thus need to be cautious when they promote development partnerships as a way to improve governance. Donor-funded partnerships are often unable to do that. Changing the attitudes of government officials requires that when planning such interventions donor agencies need to consider not only the technical side of the project but also the incentive structures that its aid package is to introduce into the system. Offering strong material incentives to NGOs can end up eroding their leaders’ voluntary commitment, and thereby their ability to apply the long-term commitment required to win the cooperation of the community as well as the government officials.

It is, however, important to note that there can be an argument for supporting state–NGO partnerships for more simple objectives, such as transfer of technical expertise from the NGOs to the state agencies. In that case, it is important that the development discourse around partnerships recognizes this difference. The reason why it is important to recognize the limitations of the technical transfers versus embedded partnerships is that the outcomes of the two are very different. Transfer of skills does not in itself lead to long-term change in government operating practices, or in the attitudes of the government officials; such collaborations thus are unable to improve delivery of social services on a long-term basis, unlike embedded partnerships.

Notes

Incentives for supporting such collaborative arrangements can take different form such as direct receipt of high per diems for participation in conferences and other activities or opportunities for joining these projects on sabbatical and receiving lucrative salary packages. Under some partnership arrangements, the government officials benefit from their offices being supplied with new vehicles, computers, photocopying machines, etc.

Between 2000 and 2010, Pakistan has been one of the largest recipients of aid from major bilateral donors, such as DFID.

This distorted political economy of the devolution program in Pakistan was openly discussed by my field respondents and media outlets.

During the fieldwork, it was widely noted that appointing members of the NGO sector as advisers to the government helped to legitimize the government in the eyes of the Western governments and international development agencies.

General Musharraf’s party lost the 2008 parliamentary elections; the alliance between the Musharraf government and donors to forge partnerships in development thus lasted primarily from 2001 to 2008.

Information about the donors supporting the Rural Support Network, including the PRSP, can be accessed at http://rspn.org/; and, http://prsp.org.pk/Home/Home.aspx.

Information about the donors with whom ITA has worked can be accessed at http://www.itacec.org.

References

Banks, N., Hulme, D., & Edwards, M. (2015). NGOs, states, and donors revisited: Still too close for comfort? World Development,66, 707–718.

Bano, M. (2008a) Public private partnerships (PPPs) as ‘anchor’ of educational reforms: Lessons from Pakistan. EFA Global Monitoring Report 2009. Paris: UNESCO.

Bano, M. (2008b). Dangerous correlations: Aid’s impact on NGO’s performance and ability to mobilize in Pakistan. World Development,36(11), 2297–2313.

Bano, M. (2012). Breakdown in Pakistan: How aid is eroding institutions for collective action. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Brinkerhoff, J. M. (2002). Government–nonprofit partnership: A defining framework. Public Administration and Development,22(1), 19–30.

Brinkerhoff, J. M. (2003). Donor-funded government–NGO partnership for public service improvement: Cases from India and Pakistan. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations,14, 105–122.

Coston, J. M. (1998). A model and typology of government-NGO relationships. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly,27(3), 358–382.

Evans, P. (1996a). Introduction: Development strategies across the public-private divide. World Development,24, 1033–1037.

Evans, P. (1996b). Government action, social capital and development: Reviewing the evidence on synergy. World Development,24, 1119–1132.

Fowler, A. F. (Ed.) (2000). Questioning partnership: The reality of aid and NGO relations. IDS Bulletin, 31(3).

Hasan, A. (1999). Planning for Karachi: An agenda for citizen and NGOs. Karachi: OPP-RTI.

Hasan, A. (2000). Scaling up of the Orangi pilot project programmes: Successes, failure and potential. Karachi: OPP-RTI.

Hatcher, P., Shaikh, S., Fazli, H., Zaidi, S., & Riaz, A. (2014). Provider cost analysis support results-based contracting out of maternal and newborn health services: An evidence-based policy perspective. BMC Health Services Research,14, 459.

Hulme, D., & Edwards, M. (1997). NGOs, states and donors: An overview. In D. Hulme & M. Edwards (Eds.), NGOs, states and donors: Too close for comfort?. New York: St. Martin’s Press in association with Save the Children.

Ismail, Z. H. (1999). Impediments to social development in Pakistan. The Pakistan Development Review.,38(4 Part II), 717–738.

Joshi, A., & Moore, M. (2004). Institutionalised co-production: Unorthodox public service delivery in challenging environment. Journal of Development Studies,40(4), 31–49.

Khan, H. K. (1998). Orangi pilot project: Reminiscences and reflections. Karachi: Oxford University Press.

MHHDC. (2016). Human development in South Asia 2016. Lahore: Mahbub-ul-Haq Human Development Center.

Ostrom, E. (1996). Crossing the great divide: Coproduction, synergy, and development. World Development,24, 1073–1087.

Teamey, K. (2007). Whose public action? Analysing inter-sectional collaboration for service delivery: Literature review on relationships between government and non-state providers of services. Birmingham: University of Birmingham, International Development Department.

Tendler, P. J. (1998). Good government in the tropics. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

World Bank. (2006a) Partnering with NGO’s to strengthen management: An external evaluation of the chief minister’s initiative on primary health care in Rahim Yar Khan District, Punjab. The World Bank South Asia Human Development Unit. Report No. 13.

World Bank. (2006b). Participatory rural sanitation in Southern Punjab: Sanitation for all in rural areas: Pollution—A challenge dead on. Lodhran Pilot Project. Japan Social Development Fund.

Acknowledgement

The author will like to acknowledge support from the Economic and Social Research Council (RES-155-25-0045) and the Oxford Department of International Development Research Fund to undertake fieldwork in Pakistan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bano, M. Partnerships and the Good-Governance Agenda: Improving Service Delivery Through State–NGO Collaborations. Voluntas 30, 1270–1283 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9937-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9937-y