Abstract

There is a profound absence of knowledge of infestation prevalence and host-use by mistletoes of mature South American tropical rainforests. In this study, we fill this gap using information gathered from felled trees at a logging concession area in Amazonian Brazil. We sampled individuals of 18 tree species, which occurred in two forest physiognomies; open forest with canopy interrupted by palm trees and closed, denser forest, with emergent trees. We hypothesized that infection incidence would be higher in open than in closed forest, irrespective of the mistletoe species involved. In addition, we expected that mistletoe parasitism would be higher on host species that were more abundant, taller, deciduous, and had less dense wood. We sampled 870 individual trees in both sites combined. All but one host species was infected by at least one species of mistletoe. We found 13 mistletoe species/morphospecies, Loranthaceae (7) and Viscaceae (6), parasitizing very different hosts. Mistletoe infection incidence was higher in the closed forest (10.3%) than in the open forest (5.4%). In the closed forest, host height influenced incidence positively, while deciduousness had a negative influence. Our results show that mistletoes are common in the canopy of pristine tropical forests and, contrary to expectations, that infection incidence was higher in the closed forest. The positive relation between infection incidence and host height in this forest type suggests that emergent trees have higher chances of being infected than individuals of correspondent species in the lower forest layers.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Adis J, Basset Y, Floren A, Hammond PM, Linsenmair KE (1998) Canopy fogging of an overstory tree—recommendations for standardization. Ecotropica 4:93–97

Arruda R, Carvalho LN, Del-Claro K (2006) Host specificity of a Brazilian mistletoe Struthanthus aff. polyanthus (Loranthaceae), in cerrado tropical savanna. Flora 201:127–134

Arruda R, Fadini RF, Carvalho LN, Del-Claro K, Mourão FA, Jacobi CM, Teodoro GS, Van Den Berg E, Caires CS, Dettke GA (2012) Ecology of neotropical mistletoes: an important canopy-dwelling component of Brazilian ecosystems. Acta Bot Bras 26:264–274. doi:10.1590/S0102-33062012000200003

Aukema JE, del Rio MC (2002) Where does a fruit-eating bird deposit mistletoe seeds? Seed deposition patterns and an experiment. Ecology 83:3489–3496

Barbosa J, Sebastián-Gonzáles E, Asner G, Knapp D, Anderson C, Martin R, Dirzo R (2016) Hemiparasite—host plant interactions in a fragmented landscape assessed via imaging spectroscopy and LiDAR. Ecol Appl 26:55–66. doi:10.1890/14.2429.1/suppinfo

Benzing DH (1990) Vascular epiphytes. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Bickford CP, Kolb TE, Geils BW (2005) Host physiological condition regulates parasitic plant performance: Arceuthobium vaginatum subsp. cryptopodum on Pinus ponderosa. Oecologia 146:179–189. doi:10.1007/s00442-005-0215-0

Blick RAJ, Burns KC, Moles AT (2013) Dominant network interactions are not correlated with resource availability: a case study using mistletoe host interactions. Oikos 122:889–895. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0706.2012.20870.x

Castilho CV, Magnusson WE, de Araújo RNO, Luizão RCC, Luizão FJ, Lima AP, Higuchi N (2006) Variation in aboveground tree live biomass in a central Amazonian forest: effects of soil and topography. For Ecol Manag 234:85–96. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2006.06.024

Chave J, Muller-Landau HC, Baker TR, Easdale TA, ter Steege H, Webb CO (2006) Regional and phylogenetic variation of wood density across 2456 neotropical tree species. Ecol Appl 16:2356–2367. doi:10.1890/1051-0761(2006)016[2356:RAPVOW]2.0.CO;2

Crawley MJ (2007) The R book. Wiley, West Sussex

Daugherty CM, Mathiasen RL (2003) Estimates of the incidence of mistletoes in pinyon-juniper woodlands of the Cocconino National Forest, Arizona. West N Am Nat 63:382–390

de Buen LL, Ornelas JF, García-Franco JG (2002) Mistletoe infection of trees located at fragmented forest edges in the cloud forests of Central Veracruz, Mexico. For Ecol Manag 164:293–302

Dzerefos CM, Witkowski ETF, Shackleton CM (2003) Host-preference and density of woodrose-forming mistletoes (Loranthaceae) on savanna vegetation, South Africa. Plant Ecol 167:163–177

Ehleringer JR, Marshall JD (1995) Water relations. In: Press MC, Graves JD (eds) Parasitic plants. Chapman & Hall, London, pp 125–140

Ehleringer JR, Schulze E-D, Ziegler H, Lange OL, Farquhar GD, Cowar IR (1985) Xylem-tapping mistletoes: water or nutrient parasites? Science 227:1479–1481

Espírito-Santo FDB, Shimabukuro YE, Aragão LEOC, Machado ELM (2005) Análise da composição florística e fitossociológica da Floresta Nacional do Tapajós com o apoio geográfico de imagens de satélites. Acta Amaz 35:155–173

Fadini RF, Cintra R (2015) Modeling occupancy of hosts by mistletoe seeds after accounting for imperfect detectability. PLoS ONE 10:e0127004. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0127004

Fadini RF, Lima AP (2012) Fire and host abundance as determinants of the distribution of three congener and sympatric mistletoes in an amazonian savanna. Biotropica 44:27–34. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7429.2011.00773.x

Genini J, Côrtes MC, Guimarães PR, Galetti M (2012) Mistletoes play different roles in a modular host-parasite network. Biotropica 44:171–178. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7429.2011.00794.x

Hawksworth FG (1983) Mistletoes as forest parasites. In: Calder M, Bernhardt P (eds) The biology of mistletoes. Academic Press, Sydney, pp 317–333

Hopkins MJG (2007) Modelling the known and unknown plant biodiversity of the Amazon Basin. J Biogeogr 34:1400–1411. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2007.01737.x

Kartoolinejad D, Hosseini SM, Mirnia SK, Akbarinia M, Shayanmehr F (2007) The relationship among infection intensity of Viscum album with some ecological parameters of host trees. Int J Environ Res 1:143–149

Kavanagh PH, Burns KC (2012) Mistletoe macroecology: spatial patterns in species diversity and host use across Australia. Biol J Linn Soc 106:459–468

Kuijt J (1969) The biology of parasitic flowering plants. University of California Press, Berkeley

Lorenzi H (2009) Árvores brasileiras. Editora Plantarum, Nova Odessa

Lorenzi H (2014a) Árvores brasileiras, 6th edn. Editora Plantarum, Nova Odessa

Lorenzi H (2014b) Árvores brasileiras, 4th edn. Editora Plantarum, Nova Odessa

Lowman MD (2004) Tarzan or Jane? A short history of canopy biology. In: Erwin TL (ed) Forest canopies. Academic Press, Waltham, pp 453–464

Lowman MD, Wittman PK (1996) Forest canopies: methods, hypotheses, and future directions. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 27:55–81. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.27.1.55

Lowman MD, Rinker HB (2004) Forest canopies. Academic Press, San Diego

Luttge U, Haridasan M, Fernandes GW, de Mattos EA, Trimborn P, Franco AC, Caldas LS, Ziegler H (1998) Photosynthesis of mistletoes in relation to their hosts at various sites in tropical Brazil. Trees 12:167–174

March WA, Watson DM (2010) The contribution of mistletoes to nutrient returns: evidence for a critical role in nutrient cycling. Austral Ecol 35:713–721

Mathiasen RL, Nickrent DL, Shaw DC, Watson DM (2008) Mistletoes: pathology, systematics, ecology and management. Plant Dis 92:988–1006

Medel R, Vergara E, Silva A, Kalin-Arroyo M (2004) Effects of vector behavior and host resistance on mistletoe aggregation. Ecology 85:120–126

Nadkarni NM, Parker GG, Lowman MD (2011) Forest canopy studies as an emerging field of science. Ann For Sci 68:217–224. doi:10.1007/s13595-011-0046-6

Nickrent DL (2011) Santalales (including mistletoes). In: Der JP (ed) Encyclopedia of life sciences. Wiley, Chichester, pp 1–6

Norton DA, Reid N (1997) Lessons in ecosystem management from management of threatened and pest Loranthaceous mistletoes in New Zealand and Australia. Conserv Biol 11:759–769

Norton DA, Carpenter MA (1998) Mistletoes as parasites: host specificity and speciation. Trends Ecol Evol 13:101–105

Norton DA, Smith MS (1999) Why might roadside mulgas be better mistletoe hosts? Aust J Ecol 24:193–198

Norton DA, Ladley JJ, Owen HJ (1997) Distribution and population structure of the loranthaceous mistletoes Alepis flavida, Peraxilla colensoi, and Peraxilla tetrapetala within two New Zealand Nothofagus forests. N Z J Bot 35:323–336

Pan Y, Birdsey RA, Fang J, Houghton R, Kauppi PE, Kurz WA, Phillips OL, Shvidenko A, Lewis SL, Canadell JG, Ciais P, Jackson RB, Pacala SW, McGuire AD, Piao S, Rautiainen A, Sitch S, Hayes D (2011) A large and persistent carbon sink in the world’s forests. Science 333:988–993. doi:10.1126/science.1201609

Queijeiro-Bolaños ME, Cano-Santana Z, Castellanos-Vargas I (2011) Distribución diferencial de dos especies de muérdago enano sobre. Acta Bot Mex 96:49–57

R Development Core Team (2012) R: a language and environment for statistical computing

Reid N, Stafford-Smith DM, Venables WN (1994) Effect of mistletoes (Amyema preissii) on host (Acacia victoriae) survival. Aust J Ecol 17:219–222

Restrepo C, Sargent S, Levey DJ, Watson DM (2002) The role of vertebrates in the diversification of new world mistletoes. In: Levey DJ, Silva WR, Galetti M (eds) Seed dispersal and frugivory: ecology, evolution and conservation. CABI Publishing, Wallingford, pp 83–98

Rist L, Shaanker RU, Ghazoul J (2011) The spatial distribution of mistletoe in a southern Indian tropical forest at multiple scales. Biotropica 43:50–57

Rodríguez-Cabal M, Aizen M, Novaro A (2007) Habitat fragmentation disrupts a plant-disperser mutualism in the temperate forest of South America. Biol Conserv 139:195–202. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2007.06.014

Roxburgh L, Nicolson SW (2005) Patterns of host use in two African mistletoes: the importance of mistletoe-host compatibility and avian disperser behaviour. Funct Ecol 19:865–873. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2005.01036.x

Sabogal C, Silva JNM, Zweede J, Pereira R, Barreto P, Guerreiro CA (2000) Diretrizes técnicas para a exploração de impacto reduzido em operações florestais de terra firme na Amazônia brasileira. Embrapa Amazônia Oriental, Belém

Sargent S (1995) Seed fate in a tropical mistletoe: the importance of host twig size. Funct Ecol 9:197–204. doi:10.2307/2390565

Scalon MC, Haridasan M, Franco A (2013) A comparative study of aluminium and nutrient concentrations in mistletoes on aluminium-accumulating and non-accumulating hosts. Plant Biol 15:851–857. doi:10.1111/j.1438-8677.2012.00713.x

Scharpf RF (1972) Light affects penetration and infection of pines by dwarf mistletoe. Phytopathology 62:1271–1273

Stropp J, Ter Steege H, Malhi Y (2009) Disentangling regional and local tree diversity in the Amazon. Ecography 32:46–54. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0587.2009.05811.x

Swenson NG, Enquist BJ (2008) The relationship between stem and branch wood specific gravity and the ability of each measure to predict leaf area. Am J Bot 95:516–519

Teodoro GS, van den Berg E, Arruda R (2013) Metapopulation dynamics of the mistletoe and its host in savanna areas with different fire occurrence. PLoS ONE 8:e65836. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065836

Veríssimo A, Cochrane MA, Souza C Jr (2002) National forests in the Amazon. Science 297:1478

Watson DM (2001) Mistletoe—a keystone resource in forests and woodlands worldwide. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 32:219–249. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114024

Watson DM (2004) Mistletoe—a unique constituent of canopies worldwide. In: Loman M, Rinker B (eds) Forest canopies. Academic Press, New York, pp 212–223

Zuur A, Leno EN, Walker N, Saveliev AA, Smith GM (2009) Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R. Springer, New York

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the help of our field assistants, Mr. Sabbat and Eucielde Pantoja de Oliveira, and the logistical support of Coomflona. We thank the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) for the scholarship granted to the first author and the Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio) for authorizing research in a Conservation Unit (SISBIO 36066). Rafael Arruda, Ricardo Scoles, Ademir Ruschel, and two anonymous reviewers made important contributions to the early versions of the manuscript. Adrian Barnett helped with the English. This is publication 19 of Parasitic Plants Research Group.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by E. T. F. Witkowski.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Fig. S1

Maps of sampled host tree species. a In open tropical forest with palms (JPEG 880 kb)

Fig. S1

Maps of sampled host tree species. b In dense tropical forest with emergent trees. Courtesy of Marcelo Brasa Santos (JPEG 932 kb)

Fig. S2

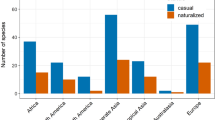

Interaction network formed by mistletoes and the host composed of trees extracted from two logging areas. Lines connect hosts of the same species in both areas (pink = dense forest, blue = open forest). Courtesy of Marco Mello (PDF 274 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lira, J., Caires, C.S. & Fadini, R.F. Reaching the canopy on the ground: incidence of infection and host-use by mistletoes (Loranthaceae and Viscaceae) on trees felled for timber in Amazonian rainforests. Plant Ecol 218, 251–263 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11258-016-0683-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11258-016-0683-9