Abstract

Although providing feedback is commonly practiced in education, there is no general agreement regarding what type of feedback is most helpful and why it is helpful. This study examined the relationship between various types of feedback, potential internal mediators, and the likelihood of implementing feedback. Five main predictions were developed from the feedback literature in writing, specifically regarding feedback features (summarization, identifying problems, providing solutions, localization, explanations, scope, praise, and mitigating language) as they relate to potential causal mediators of problem or solution understanding and problem or solution agreement, leading to the final outcome of feedback implementation. To empirically test the proposed feedback model, 1,073 feedback segments from writing assessed by peers was analyzed. Feedback was collected using SWoRD, an online peer review system. Each segment was coded for each of the feedback features, implementation, agreement, and understanding. The correlations between the feedback features, levels of mediating variables, and implementation rates revealed several significant relationships. Understanding was the only significant mediator of implementation. Several feedback features were associated with understanding: including solutions, a summary of the performance, and the location of the problem were associated with increased understanding; and explanations of problems were associated with decreased understanding. Implications of these results are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We use the term mediator because the variables of understanding and agreement are thought to mediate between external features and implementation. However, we cannot apply formal mediation statistical tests on this dataset because of the reduced Ns associated with the mediating variables. We do note, however, that the correlation found from external features to mediator variables as well mediators to implementation are always stronger than the direct “correlation” between external features and implementation, and thus mediation relationships are quite consistent with the statistical patterns in the data.

References

Bangert-Drowns, R. L., Kulik, C. C., Kulik, J. A., & Morgan, M. T. (1991). The instruction effect of feedback in test-like events. Review of Educational Research, 61(2), 218–238.

Bitchener, J., Young, S., & Cameron, D. (2005). The effect of different types of corrective feedback on ESL student writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 14, 191–205.

Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (Eds.) (2003). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington DC: National Academy Press.

Bransford, J. D., & Johnson, M. K. (1972). Contextual prerequisites for understanding: Some investigations of comprehension and recall. Journal of verbal learning and verbal behavior, 11, 717–726.

Brockner, J., & Higgins, E. T. (2001). Regulatory foccus theory: Implications for the study of emotions at work. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86(1), 35–66.

Brown, F. J. (1932). Knowledge of results as an incentive in school room practice. Journal of Educational Psychology, 23(7), 532–552.

Chi, M. T. H., Bassok, M., Lewis, M. W., Reimann, P., & Glaser, R. (1989). Self-Explanations: How students study and use examples in learning to solve problems. Cognitive Science, 13, 145–182.

Cho, K., & Schunn, C. D. (2007). Scaffolded Writing and Rewriting in the Discipline: A web-based reciprocal peer review system. Computers & Education, 48(3), 409–426.

Cho, K., Schunn, C. D., & Charney, D. (2006). Commenting on writing: Typology and perceived helpfulness of comments from novice peer reviewers and subject matter experts. Written Communication, 23(3), 260–294.

Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1040–1048.

Dweck, C. S., & Leggert, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256–273.

Ferris, D. R. (1997). The influence of teacher commentary on student revision. TESOL Quarterly, 31(2), 315–339.

Gick, M. L., & Holyoak, K. J. (1980). Analogical problem solving. Cognitive Psychology, 12, 306–355.

Gick, M. L., & Holyoak, K. J. (1983). Schema induction and analogical transfer. Cognitive Psychology, 15, 1–38.

Grimm, N. (1986). Improving students’ responses to their peers’ essays. College Composition and Communication, 37(1), 91–94.

Haswell, R. H. (2005). NCTE/CCCC’s recent war on scholarship. Written Communication, 22(2), 198–223.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112.

Hayes, J. R. (1996). A new framework for understanding cognition and affect in writing. In L. W. Gregg, & E. R. Steinberg (Eds.), The science of writing (pp. 1–27). Mahwah, New Jersey: Erlbaum.

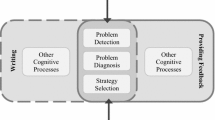

Hayes, J. R., Flower, L., Schriver, K. A., Stratman, J., & Carey, L. (1987). Cognitive processes in revision. In S. Rosenberg (Ed.), Advances in applied psycholinguistics, Volume II: Reading, writing, and language processing (pp. 176–240). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Hull, C. L. (1935). Thorndike’s fundamentals of learning. Psychological Bulletin, 32, 807–823.

Hyland, F., & Hyland, K. (2001). Sugaring the pill Praise and criticism in written feedback, Jouranl of Second Language Writing, 10, 185–212.

Ilgen, D. R., Fisher, C. D., & Taylor, M. S. (1979). Consequences of individual feedback on behavior in organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 64(4), 349–371.

Kellogg, R. T. (1996). A model of working memory in writing. In L. W. Gregg, & E. R. Steinberg (Eds.), The science of writing (pp. 57–71). Mahwah, New Jersey: Erlbaum.

Kieras, D. E., & Bovair, S. (1984). The role of a mental model in learning to operate a devise. Cognitive Science, 8, 255–273.

Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin, 119(2), 254–284.

Kulhavy, R. W., & Stock, W. A. (1989). Feedback in written instruction: The place of response certitude. Educational Psychology Review, 1(4), 279–308.

Kulhavy, R. W., & Wager, W. (1993). Feedback in programmed instruction: Historical context and implications for practice. In J. V. Dempsey, & G. C. Sales (Eds.), Interactive instruction and feedback (pp. 3–20). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology.

Landis, J. R., Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174.

Lin, S. S. J., Liu, E. Z. F., & Yuan, S. M. (2001). Web-based peer assessment: Feedback for students with various thinking-styles. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 17(4), 420–432.

Matsumura, L. C., Patthey-Chavez, G. G., Valdes, R., & Garnier, H. (2002). Teacher feedback, writing assignment quality, and third-grade students’ revision in lower- and higher-achieving urban schools. The Elementary School Journal, 103(1), 3–25.

McCutchen, D. (1996). A capacity theory of writing: Working memory in composition. Educational Psychological Review, 8(3), 299–325.

Miller, P. J. (2003). The effect of scoring criteria specificity on peer and self-assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 28(4), 383–394.

Mory, E. H. (1996). Feedback research. In D.H. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of research for educational communications and technology (pp. 919–956). New York: Simon & Schuster Macmillan.

Mory, E. H. (2004). Feedback research revisited. In D.H. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of research for educational communications and technology Second Edition (pp. 745–783). Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Neuwirth, C. M., Chandhok, R., Charney, D., Wojahn, P., & Kim, L. (1994). Distributed Collaborative writing: A comparison of spoken and written modalities for reviewing and revising documents. Proceedings of the Computer-Human Interaction ‘94 Conference, April 24–28, 1994, Boston Massachusetts (pp. 51–57). New York: Association for Computing Machinery.

Newell, A., & Simon, H. A. (1972). Human problem solving. Englewoods Clis, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Nilson, L. B. (2003). Improving student peer feedback. College Teaching, 51(1), 34–38.

Novick, L. R., & Holyoak, K. J. (1991). Mathematical problem solving by analogy. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 17(3), 398–415.

Olson, M. W., & Raffeld, P. (1987). The effects of written comments on the quality of student compositions and the learning of content. Reading Psychology: An International Quarterly, 8, 273–293.

Pressey, S. L. (1926). A simple device which gives tests and scores—and teaches. School and Society, 23, 373–376.

Pressey, S. L. (1927). A machine for automatic teaching of drill material. School and Society, 25, 549–552.

Roediger, H. L. (2007). Twelve Tips for Reviewers. APS Observer, 20(4), 41–43.

Saddler, B., & Andrade, H. (2004). The writing rubric. Educational Leadership, 62(2), 48–52.

Shah, J., & Higgins, E. T. (1997). Expectancy X value effects: Regulatory focus as determinant of magnitude and direction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(3), 447–458.

Sternberg, R. J. (2002). On civility in reviewing. APS Observer, 15(1).

Sugita, Y. (2006). The impact of teachers’ comment types on students’ revision. ELT Journal, 60(1), 34–41.

Symonds, P. M., & Chase, D. H. (1929). Practice vs. motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 20(1), 19–35.

Thorndike, E. L. (1927). The law of effect. American Journal of Psychology, 39(1/4), 212–222.

Toegel, G., & Conger, J. A. (2003). 360-degree assessment: Time for Reinvention. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 2(3), 297–311.

Tseng, S.-C., & Tsai, C.-C. (2006). On-line peer assessment and the role of the peer feedback: A study of high school computer course. Computers & Education.

Wallace, D. L., & Hayes, J. R. (1991). Redefining revision for freshman. Research in the Teaching of English, 25, 54–66.

Wallach, H., & Henle, M. (1941). An experimental analysis of the Law of Effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 28, 340–349.

Wigfield, A., & Guthrie, J. T. (1997). Relations of children’s motivation for reading and the amount of breadth of their reading. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(3), 420–432.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by A.W. Mellon Foundation. Thanks to Danikka Kopas, Jennifer Papuga, and Brandi Melot for all their time coding data. Also thanks to Lelyn Saner, Elisabeth Ploran, Chuck Perfetti, Micki Chi, Michal Balass, Emily Merz, and Destiny Miller for their comments on earlier drafts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix A: Reviewing guidelines

Appendix A: Reviewing guidelines

General reviewing guidelines

There are two very important parts to giving good feedback. First, give very specific comments rather than vague comments: Point to exact page numbers and paragraphs that were problematic; give examples of general problems that you found; be clear about what exactly the problem was; explain why it was a problem, etc. Second, make your comments helpful. The goal is not to punish the writer for making mistakes. Instead your goal is to help the writer improve his or her paper. You should point out problems where they occur. But don’t stop there. Explain why they are problems and give some clear advice on how to fix the problems. Also keep your tone professional. No personal attacks. Everyone makes mistakes. Everyone can improve writing.

Prose transparency

Did the writing flow smoothly so you could follow the main argument? This dimension is not about low level writing problems, like typos and simple grammar problems, unless those problems are so bad that it makes it hard to follow the argument. Instead this dimension is about whether you easily understood what each of the arguments was and the ordering of the points made sense to you. Can you find the main points? Are the transitions from one point to the next harsh, or do they transition naturally?

Your comments: First summarize what you perceived as the main points being made so that the writer can see whether the readers can follow the paper’s arguments. Then make specific comments about what problems you had in understanding the arguments and following the flow across arguments. Be sure to give specific advice for how to fix the problems and praise-oriented advice for strength that made the writing good.

Logic of the argument

This dimension is about the logic of the argument being made. Did the author just make some claims, or did the author provide some supporting arguments or evidence for those claims? Did the supporting arguments logically support the claims being made or were they irrelevant to the claim being made or contradictory to the claim being made? Did the author consider obvious counter-arguments, or were they ignored?

Your comments: Provide specific comments about the logic of the author’s argument. If points were just made without support, describe which ones they were. If the support provided doesn’t make logical sense, explain what that is. If some obvious counter-argument was not considered, explain what that counter-argument is. Then give potential fixes to these problems if you can think of any. This might involve suggesting that the author change their argument.

Insight beyond core readings

This dimension concerns the extent to which new knowledge is introduced by a writer. Did the author just summarize what everybody in the class would already know from coming to class and doing the assigned readings, or did the author tell you something new?

Your comments: First summarize what you think the main insights were of this paper. What did you learn if anything? Listing this clearly will give the author clear feedback about the main point of writing a paper: to teach the reader something. If you think the main points were all taken from the readings or represent what everyone in the class would already know, then explain where you think those points were taken or what points would be obvious to everyone. Remember that not all points in the paper need to be novel, because some of the points need to be made just to support the main argument.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nelson, M.M., Schunn, C.D. The nature of feedback: how different types of peer feedback affect writing performance. Instr Sci 37, 375–401 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-008-9053-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-008-9053-x