Abstract

We address the problem of initiation of convective motion in the case of a fluid saturated porous layer, containing a salt in solution, which is heated and salted below. We amplify the very interesting recent results of Nield and Kuznetsov and examine in detail a whole range of temperature and salt boundary conditions allowing for a combination of prescribed heat flux and temperature. The behaviour of the transition from stationary to oscillatory convection is examined in detail as the boundary conditions vary from prescribed temperature and salt concentration toward those of prescribed heat flux and salt flux.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Nield and Kuznetsov (2016) produced an inspiring article in which they address the behaviour of the onset of convective motion in a layer of porous material which is saturated by a fluid containing a dissolved salt. They consider both Brinkman and Darcy theory, and they are primarily interested in the case where the heat flux and salt flux are prescribed on the boundary. They do, however, also consider the case where general thermal and salt boundary conditions are employed which involve a combination of flux and prescribed temperature and salt. They develop an asymptotic and a numerical analysis to study how oscillatory convection behaves as boundary conditions of flux only are considered. It is well known that in the heated below–salted below situation there is a transition from stationary convection to oscillatory convection as the salt Rayleigh number increases. The current article is motivated entirely by the work of Nield and Kuznetsov (2016), and we analyse how the transition from stationary to oscillatory convection is affected as the boundary conditions change.

Double diffusive convection is a problem with many real-life applications and as such has attracted much attention in the research literature, see, e.g. Barletta and Nield (2011), Deepika (2018), Deepika and Narayana (2016), Harfash and Challoob (2018), Harfash and Hill (2014), Joseph (1970), Joseph (1976), Lombardo et al. (2001), Matta et al. (2017), Mulone (1994), Nield (1967, 1968), Nield and Kuznetsov (2016), Straughan (2011, 2014, 2015a, 2018, 2019) and Xu and Li (2019). Stability analyses in double diffusive convection were introduced in the fundamental articles of Nield (1967, 1968), and from an unconditional energy stability point of view by Joseph (1970, 1976). Research activity in this area has increased rapidly as is witnessed by the articles cited above and the references therein.

Another very interesting development in stability in thermal convection studies has been to consider boundary conditions which are more general than those of prescribing temperature and salt concentration. For example, isoflux conditions, isobaric conditions, or various combinations. In many cases, these boundary conditions lead to surprising and novel results, see, e.g. Barletta (2012), Barletta et al. (2010), Barletta and Rees (2012), Barletta and Celli (2018), Celli and Barletta (2019), Celli et al. (2016), Celli et al. (2013), Celli and Kuznetsov (2018), Falsaperla et al. (2010, 2011), Lagziri and Bezzazi (2019), McKibbin (1986), Mohammad and Rees (2017), Nield and Kuznetsov (2016), Rees and Barletta (2011), Rees and Mojtabi (2011), Rees and Mojtabi (2013), Salt (1988) and Webber (2006).

Given the interest in double diffusive convection, especially where the salt and temperature effects are in competition as in the heated and salted below case, and the attention to general boundary conditions where a combination of flux and prescribed temperature/salt is studied, we believe this work is noteworthy. We also corroborate some of the findings of Nield and Kuznetsov (2016) as boundary conditions of pure flux are approached.

2 Equations

The derivation of the equations for double diffusion in a porous layer is well known. We present the non-dimensional perturbation equations in terms of the velocity, pressure, temperature and concentration perturbations, \(u_i,\pi ,\theta \) and \(\phi \), cf. Nield and Kuznetsov (2016), Mulone (1994) and Straughan (2014), Eq. (5),

where R and C are the Rayleigh and salt Rayleigh numbers, \(\mathbf{k}=(0,0,1)\), \(\epsilon _1=\epsilon Le\), where \(\epsilon \) is the porosity and Le is the Lewis number, \(\Delta \) is the Laplace operator, and standard indicial notation is employed. Equation (1) holds in the layer \(\{(x,y)\in \mathbb {R}^2\}\times \{z\in (0,1)\}\) with \(t>0\).

The boundary conditions may be derived as in Nield and Kuznetsov (2016), where the temperature and concentration are specified on the boundaries \(z=0,1\) and the perturbations are subject to more general boundary conditions. Alternatively, in the dimensional variables, we may propose the temperature satisfies the boundary conditions

where d is the layer depth, \(T_L\) and \(T_U\) are constants with \(T_L>T_U\), \(\beta =(T_L-T_U)/d\) and \(\alpha \) is a constant with \(0\le \alpha < 1\). Note that \(\alpha =0\) corresponds to prescribed upper and lower temperatures \(T_U\) and \(T_L\), whereas \(\alpha =1\) corresponds to flux boundary conditions. Equation (2) is usually known as Robin boundary conditions, and they allow a steady solution

and then lead to the non-dimensional perturbation boundary conditions

where \(\theta \) is the non-dimensional temperature perturbation. We introduce the parameter \(L=(1-\alpha )/\alpha \) (the Biot number) and note that (3) may be rewritten as

A similar derivation involving the concentration C leads to non-dimensional perturbation boundary conditions on \(\phi \) as

We here restrict attention to the case where L has the same value in (4) and (5). One could consider a general case where four different L values, \(L_i,\)\(i=1,\ldots ,4,\) are considered in (4) and (5).

We are interested in determining the threshold of instability and so we remove the nonlinear terms from (1) and then seek a solution like \(u_i=u_i(\mathbf{x})\,e^{\sigma t}\), \(\pi =\pi (\mathbf{x})\,e^{\sigma t}, \theta =\theta (\mathbf{x})\,e^{\sigma t}\), \(\phi =\phi (\mathbf{x})\,e^{\sigma t}\). We next remove the pressure by taking curlcurl of (1)\(_1\) and retain the third component of the resulting equation. Writing \(\mathbf{u}=(u,v,w)\), this leaves the system of equations

where \(\Delta ^*=\partial ^2/\partial x^2+\partial ^2/\partial y^2\). This system is to be solved subject to boundary conditions (4), (5), together with

and the assumption that \(w,\theta ,\phi \) satisfy a periodic plane tiling planform in (x, y) (Chandrasekhar 1981, pp. 43–52).

The plane tiling planform h(x, y) is discussed at length in cf. Chandrasekhar (1981), pp. 43–52, and satisfies \(\Delta ^*h=-a^2h\), where a is a wavenumber. This allows one to decompose \(w,\theta ,\phi \) in terms of functions of form \(w=W(z)h(x,y)\), \(\theta =\Theta (z)h(x,y)\) and \(\phi =\Phi (z)h(x,y)\). Upon using these forms, one has to solve the eigenvalue problem

and the boundary conditions

Numerical solutions of (8) and (9) are presented in Sect. 5.

3 Exact Theory

Before discussing numerical results for various values of L, we recollect results when \(L=\infty \), i.e. when \(\alpha =0\). In this case, Eqs. (8) and (9) may be solved exactly and one finds the lowest two eigenvalues lead to the stationary convection threshold

and the oscillatory convection threshold

with the oscillatory part of the eigenvalue satisfying

One may observe that curves (10) and (11) intersect at \((R^*,C^*)\) when \(\epsilon _1>1\), as is nearly always the case in real life, where

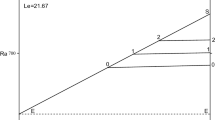

The behaviour of the (R, C) curves is shown in Fig. 1 when \(\epsilon _1=\epsilon Le=20\). In this case, the stationary convection curve has slope 1, while the oscillatory convection curve has slope 1/20. For \(C\le C^*\), one finds stationary convection, whereas for \(C>C^*\) oscillatory convection occurs.

Graph of R, C when the parameter L has infinite value (prescribed temperatures). Here, \(\epsilon Le=20\). The left branch of the solid curve is the stationary convection boundary, and the part after \((R^*,C^*)=(4\pi ^2(\epsilon Le/\epsilon Le -1),4\pi ^2/(\epsilon Le -1)),\) represents the oscillatory convection boundary. The broken line is a continuation of the stationary convection boundary

If one employs purely flux boundary conditions, it is known that \(a=0\) yields the stationary convection boundary and then I calculate a weakly nonlinear analysis to show

is the instability threshold. This suggests that \(R^*\in [12,4\pi ^2\epsilon _1/(\epsilon _1-1)]\) and \(C^*\in [12/\epsilon _1,4\pi ^2/(\epsilon _1-1)]\), for general values of L in (0,1]. Numerical analysis confirms this, and the behaviour is reported in Sect. 5.

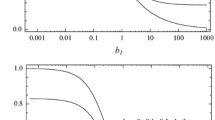

Graph of R, C when the parameter L varies. Here, \(\epsilon Le=20\). The curves decrease in R as L decreases and are for \(L=\infty \) (uppermost curve), 10, 5, 2.5, 1, 0.1, 0.01 and \(10^{-4}\) (lowest curve). The dark solid circles represent \((R^*,C^*)\). The dotted lines represent the curves \(C=1,1.7,2.1,\) cf. Tables 2, 3 and 4

Graph of \(R^*,C^*\). The parameter L varies from \(10^{-10}\) to \(\infty \). Here, \(\epsilon Le=20\). The values of L represented by the circles are \(10^{-10},10^{-8},10^{-6},10^{-4}\) shown as the four nearly coalesced circles on the lower left of the line (indistinguishable at this scale), and 0.01, 0.1, 1, 2.5, 5, 10, 100 and \(\infty \), with the last value being the circle on the upper right of the line. The dashed line for \(C^*\) between 0 and 2.5 represents the convection threshold \(R=12\)

4 Numerical Methods

The numerical methods we employ are based on the Chebyshev tau method, see, e.g. Dongarra et al. (1996) and Gheorghiu (2014), and the resulting finite dimensional generalized matrix eigenvalue problem is solved with the QZ algorithm of Moler and Stewart (1971). Explicit details of this are given in Dongarra et al. (1996), and we write

where \(T_n\) are the Chebyshev polynomials of the first kind and \(W_n,\Theta _n,\Phi _n\) are the Fourier coefficients. In terms of the vector

this leads to the matrix eigenvalue problem

where

and

Care must be taken with the boundary conditions to avoid the presence of spurious eigenvalues. Details of how one handles the boundary conditions \(W=0\) are given in Dongarra et al. (1996). To deal with the boundary conditions on \(\Theta \) and \(\Phi \), we note that \(T_n(\pm 1)=(\pm 1)^n\) and \(T_n^{\prime }(\pm 1)=(\pm 1)^{n-1}n^2\). One has to recollect that the Chebyshev domain is \((-1,1)\), and then one finds that the boundary conditions yield the restrictions

and

This allows one to write

and

Analogous expressions hold for \(\Phi _{N-1}\) and \(\Phi _N\). These expressions are used to remove boundary condition rows, cf. Dongarra et al. (1996), in the matrices A and B and are very important in dealing with spurious eigenvalues.

To find \((R^*,C^*)\) numerically is not trivial. We used two codes. One tracks along the stationary convection curve from \(C=0\) and then tracks along the oscillatory convection curve in the opposite direction. When we are in the vicinity of \((R^*,C^*)\), the two leading eigenvalues \(\sigma _1\) and \(\sigma _2\) one of which is real, whereas the other is complex, have real parts close to zero and close to each other; therefore, the code switches from one to the other and breaks down. Thus, we extrapolate from the stationary and oscillatory convection curves for a given value of L to find an approximate value for \(R^*\) and \(C^*\). We then employ a second code which compares \(\sigma _1\) and \(\sigma _2\) in the vicinity of the “crossing point” and varies over a suitable range of wavenumber a. In this way, we actually find where \(\sigma _1\) and \(\sigma _2\) swap places, to 3 decimal places of accuracy in R. Numerical results employing these procedures are presented next.

5 Numerical Results and Conclusions

The values of \(R^*\) and \(C^*\) as L varies are displayed in Table 1 and in Figs. 2 and 3. From Fig. 3, it appears that \((R^*,C^*)\) form approximately a straight line with L varying. The critical values of a are in agreement with the values in table 1 of Nield and Kuznetsov (2016), who give values of R and \(a_{\mathrm{cr}}\) as L varies for the problem of thermal convection (without a solute). We found \(R^*\in (12.631,12.632)\) and \(C^*\in (0.6315,0.6316)\) when \(L=10^{-10}\), and we found a similar value for \(C^*\) when \(L=10^{-12}\).

The critical wavenumber \(a_{\mathrm{{cr}}}\) varies with L, but we found no variation with C, as seen in Tables 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13. For \(L\le 0.1\), we found the graph of \(\log _{10}a\) against \(\log _{10}L\) yields approximately a straight line, as is seen in Fig. 4. This behaviour is already seen in the numbers of table 1 of Nield and Kuznetsov (2016). We actually found values of \(a_{\mathrm{{cr}}}\) when \(L=10^{-9},10^{-10},10^{-11}\) and \(10^{-12}\) to be \(a_{\mathrm{{cr}}}=0.01201,0.00671,0.00381\) and 0.00213, respectively.

From Tables 2–4, we see that the value of \(\sigma _i\) (the imaginary part of \(\sigma \)) on the oscillatory curve firstly increases as L decreases, reaches a maximum, and then decreases again with further decrease in L. Tables 2–4 correspond to values on the oscillatory branches of the instability curve shown in Fig. 2 for \(C=1,1.7\) and 2.1 (the dashed lines). We observe that as L becomes very small \(\sigma _i\) likewise becomes very small. This is in complete agreement with the findings of Nield and Kuznetsov (2016) who note in their conclusions (in our notation),...oscillatory instability can still occur as L tends to zero..., in practical situations it is likely that no oscillations will be observed. This behaviour is witnessed in Tables 5–13.

From Tables 5–13, we see that \(\sigma _i\) increases on the oscillatory curve as C increases, and this is in agreement with the exact case of prescribed temperature and concentration where we know the exact solution, cf. Eq. (12).

From Tables 5–13 and the exact solution when \(L=\infty \), we observe that the slope on the stationary convection curve is always 1. However, the slope on the oscillatory convection curve is 0.05 when \(L=\infty ,100\) and then increases to a maximum and then decreases again as \(L\rightarrow 0\). We found approximately, slopes of 0.0524, 0.0561, 0.0606, 0.0633, 0.0567, 0.0522, 0.0502 when \(L=10,5,2.5,1,0.1,0.01,10^{-4}\), respectively, and then for \(L=10^{-6}\) or smaller the slope is 0.05. It appears from the numerical results that the oscillatory curve is a straight line for all values of L, but we have no analysis to justify this. It is worth pointing out that while the oscillatory curve is close to a straight line for an anisotropic inertia coefficient it is not actually straight, see Straughan (2014). Also, the transition from stationary to oscillatory convection in other problems may involve curved stationary convection and oscillatory convection curves, see, e.g. the analysis of Straughan (2015b) when the heat flux is of Cattaneo–Christov type.

In conclusion, we have found the transition from stationary convection to oscillatory convection in the heated below–salted below situation when the Nield and Kuznetsov (2016) boundary conditions, (4), (5), are employed for various values of L. We have chosen for our numerical results the realistic value of \(\epsilon _1=\epsilon Le=20\), although I believe the behaviour found here is not simply restricted to this case. Our results are in agreement with those of Nield and Kuznetsov (2016), and we add further information to their findings.

References

Barletta, A.: Thermal instability in a horizontal porous channel with horizontal through flow and symmetric wall heat fluxes. Transp. Porous Med. 92, 419–437 (2012)

Barletta, A., Celli, M.: The Horton–Rogers–Lapwood problem for an inclined porous layer with permeable boundaries. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 474, 20180021 (2018)

Barletta, A., Celli, M., Nield, D.A.: Unstably stratified Darcy flow with impressed horizontal temperature gradient, viscous dissipation and asymmetric thermal boundary conditions. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 53, 1621–1627 (2010)

Barletta, A., Nield, D.A.: Thermosolutal convective instability and viscous dissipation effect in a fluid-saturated porous medium. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 54, 1641–1648 (2011)

Barletta, A., Rees, D.A.S.: Local thermal non-equilibrium effects in the Darcy–Bénard instability with isoflux boundary conditions. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 55, 384–394 (2012)

Celli, M., Alves, L.S.B., Barletta, A.: Nonlinear stability analysis of Darcy’s flow with viscous heating. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 472, 20160036 (2016)

Celli, M., Barletta, A.: Onset of buoyancy driven convection in an inclined porous layer with an isobaric boundary. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 132, 782–788 (2019)

Celli, M., Barletta, A., Storesletten, L.: Local thermal non-equilibrium effects in the Darcy–Bénard instability of a porous layer heated from below by a uniform flux. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 67, 902–912 (2013)

Celli, M., Kuznetsov, A.V.: A new hydrodynamic boundary condition simulating the effect of rough boundaries on the onset of Rayleigh–Bénard convection. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 116, 581–586 (2018)

Chandrasekhar, S.: Hydrodynamic and Hydromagnetic Stability. Dover, New York (1981)

Deepika, N.: Linear and nonlinear stability of double-diffusive convection with the Soret effect. Transp. Porous Med. 121, 93–108 (2018)

Deepika, N., Narayana, P.A.L.: Nonlinear stability of double-diffusive convection in a porous layer with throughflow and concentration based internal heat source. Transp. Porous Med. 111, 751–762 (2016)

Dongarra, J.J., Straughan, B., Walker, D.W.: Chebyshev tau-QZ algorithm methods for calculating spectra of hydrodynamic stability problems. Appl. Numer. Math. 22, 399–435 (1996)

Falsaperla, P., Mulone, G., Straughan, B.: Rotating porous convection with prescribed heat flux. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 48, 685–692 (2010)

Falsaperla, P., Mulone, G., Straughan, B.: Inertia effects on rotating porous convection. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 54, 1352–1359 (2011)

Gheorghiu, C.I.: Spectral Methods for Non-standard Eigenvalue Problems. Fluid and Structural Mechanics and Beyond. Springer, Cham (2014)

Harfash, A.J., Challoob, H.A.: Slip boundary conditions and throughflow effects on double diffusive convection in internally heated heterogeneous brinkman porous media. Chin. J. Phys. 56, 10–22 (2018)

Harfash, A.J., Hill, A.A.: Simulation of three-dimensional double-diffusive throughflow in internally heated anisotropic porous media. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 72, 609–615 (2014)

Joseph, D.D.: Global stability of the conduction–diffusion solution. Arch. Ration. Mech. Anal. 36, 285–292 (1970)

Joseph, D.D.: Stability of Fluid Motions, vol. 2. Springer, Berlin (1976)

Lagziri, H., Bezzazi, M.: Robin boundary effects in the Darcy-Rayleigh problem with local thermal non-equilibrium model. Transp. Porous Med. 129, 701–720 (2019)

Lombardo, S., Mulone, G., Straughan, B.: Nonlinear stability in the Bénard problem for a double diffusive mixture in a porous medium. Math. Meth. Appl. Sci. 24, 1229–1246 (2001)

Matta, A., Narayana, P., Hill, A.A.: Double diffusive Hadley–Prats flow in a horizontal layer with a concentration based internal heat source. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 452, 1005–1018 (2017)

McKibbin, R.: Thermal convection in a porous layer: effects of anisotropy and surface boundary conditions. Trans. Porous Med. 1, 271–292 (1986)

Mohammad, A.V., Rees, D.A.S.: The effect of conducting boundaries on the onset of convection in a porous layer which is heated from below by internal heating. Trans. Porous Med. 117, 189–206 (2017)

Moler, C.B., Stewart, G.W.: An algorithm for the generalized matrix eigenvalue problem \({A}x=\lambda {B}x\). Univ. Texas at Austin, Technical report (1971)

Mulone, G.: On the nonlinear stability of a fluid layer of a mixture heated and salted from below. Continuum. Mech. Thermodyn. 6, 161–184 (1994)

Nield, D.A.: The thermohaline Rayleigh–Jeffreys problem. J. Fluid Mech. 29, 545–558 (1967)

Nield, D.A.: Onset of thermohaline convection in a porous medium. Water Resour. Res. 4, 553–560 (1968)

Nield, D.A., Kuznetsov, A.V.: Do isoflux boundary conditions inhibit oscillatory double-diffusive convection? Trans. Porous Med. 112, 609–618 (2016)

Rees, D.A.S., Barletta, A.: Linear instability of the isoflux Darcy–Bénard problem in an inclined porous layer. Transp. Porous Med. 87, 665–678 (2011)

Rees, D.A.S., Mojtabi, A.: The effect of conducting boundaries on weakly nonlinear Darcy–Bénard convection. Transp. Porous Med. 88, 45–63 (2011)

Rees, D.A.S., Mojtabi, A.: The effect of conducting boundaries on Lapwood–Prats convection. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 65, 765–778 (2013)

Salt, H.: Heat transfer across convecting porous layers with flux boundaries. Transp. Porous Med. 3, 325–341 (1988)

Straughan, B.: Tipping points in Cattaneo–Christov thermohaline convection. Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. A 467, 7–18 (2011)

Straughan, B.: Anisotropic inertia effect in microfluidic porous thermosolutal convection. Microfluidics Nanofluidics 16, 361–368 (2014)

Straughan, B.: Convection with Local Thermal Non-equilibrium and Microfluidic Effects. Advances in Mechanics and Mathematics Series, vol. 32. Springer, Cham (2015)

Straughan, B.: Exchange of stability in Cattaneo-LTNE porous convection. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 89, 792–798 (2015)

Straughan, B.: Bidispersive double diffusive convection. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 126, 504–508 (2018)

Straughan, B.: Effect of inertia on double diffusive bidispersive convection. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 129, 389–396 (2019)

Webber, M.: The destabilizing effect of boundary slip on Bénard convection. Math. Meth. Appl. Sci. 29, 819–838 (2006)

Xu, L., Li, Z.: Global exponential nonlinear stability for double diffusive convection in a porous medium. Acta Mathematica Scientia 39, 1–8 (2019)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by an Emeritus Fellowship of the Leverhulme Trust, EM-2019-022/9. I am grateful to referees for constructive comments which have improved the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest with this work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Straughan, B. Heated and Salted Below Porous Convection with Generalized Temperature and Solute Boundary Conditions. Transp Porous Med 131, 617–631 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11242-019-01359-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11242-019-01359-y