Abstract

Choice under uncertainty is treated in economics by different approaches. We can distinguish three of them, two of which concern individual choice, while the third frames individual choices within the analysis of the social system. The first approach can determine how a rational decision-maker must choose; the second one how a real decision-maker behaves; and the third one how decision-makers are represented in the general economic theory. The main theories that result from these approaches are briefly presented. This paper considers, in particular, the third approach, which is the most general since it represents preferences by means of a continuous (ordinal) utility function of the possible outcomes, without any specification with regard to uncertainty. The link between the reservation prices of bets on events and their subjective probabilities is examined. It is shown as the additivity condition for these price-probabilities is not required by the Dutch book argument if preferences are represented by a continuous utility function that is not differentiable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The independence axiom requires, for \( \ell_{a} \succ \ell_{b} \) (i.e., lottery \( \ell_{a} \) is preferred to lottery \( \ell_{b} \)), with \( \ell_{a} ,\ell_{b} \in {\fancyscript{L}}\), where \( {\fancyscript{L}} \) is the set of the possible lotteries, that \( (\ell_{a} ,\pi ;\ell_{c} ,1 - \pi ) \succ (\ell_{b} ,\pi ;\ell_{c} ,1 - \pi ) \) for every \( \ell_{c} \in {\fancyscript{L}} \) and \( \pi \in (0,1] \), where \( \pi \) is a probability.

\( G(x_{i} ) \) indicates the probability that an outcome not inferior to \( x_{i} \) will occur.

A binary preference ordering shows, for each pair of alternatives \( a,a^{\prime} \), which alternative is chosen or that the subject is indifferent between them. If alternative \( a \) is chosen, this result is indicated with the (strong) preference relation \( a \succ a^{\prime} \). If the two alternatives are indifferent, then there is the indifference relation \( a \sim a^{\prime} \). If there is one of these two situations, that is if alternative \( a \) is chosen or the two alternatives are indifferent, then this situation is represented by the (weak) preference relation \( a \succsim a^{\prime} \). Preferences are representable with a binary ordering if the preferences identified considering pairs of alternatives can be extended to cases where choice has to be done between more than two alternatives. Thus, the binary preference ordering \( \langle A, \succsim \rangle \) indicates, for every pair \( a,a^{\prime} \in A \) with \( a \succsim a^{\prime} \), that \( a \in c(B) \) for every B with \( a,a^{\prime} \in B \). It is \( a \succ a^{\prime} \) if \( a \in c(B) \) and \( a^{\prime} \notin c(B) \), while \( a \sim a^{\prime} \) if \( a \in c(B) \) and \( a^{\prime} \in c(B) \).

Consider an individual who does not like to appear selfish and who chooses, between the available alternatives, not the one that is the most attractive (for him and for all), but the second in order of desirability. If \( A = \left\{ {a^{\prime},a^{\prime\prime},a^{\prime\prime\prime}} \right\} \), where \( a^{\prime} \) is the first alternative in terms of desirability, \( a^{\prime\prime} \) the second and \( a^{\prime\prime\prime} \) the third, then, in the choice between two alternatives considered by the binary system, he chooses the worst of the two alternatives, so they are \( a^{\prime\prime} \succ a^{\prime} \), \( a^{\prime\prime\prime} \succ a^{\prime\prime} \) and \( a^{\prime\prime\prime} \succ a^{\prime} \). However, in the choice between all three alternatives, he chooses the second in order of desirability, which is \( a^{\prime\prime} \), in contrast to the binary order that indicates \( a^{\prime\prime\prime} \succ a^{\prime\prime} \). This example does not satisfy the weak axiom of revealed preferences, since, contrarily to this axiom, \( a^{\prime\prime} \) is chosen in the set \( \left\{ {a^{\prime},a^{\prime\prime},a^{\prime\prime\prime}} \right\} \) and \( a^{\prime\prime\prime} \) is chosen in the set \( \left\{ {a^{\prime\prime},a^{\prime\prime\prime}} \right\} \).

Completeness requires that, for every pair \( a,a^{\prime} \in A \), we have \( a \succsim a^{\prime}\) and/or \( a^{\prime} \succsim a\). Transitivity requires that, if \( a\succsim a^{\prime}\) and \( a^{\prime} \succsim a^{\prime\prime} \), then we have also \( a \succsim a^{\prime\prime} \) with \( a \succ a^{\prime\prime} \) if at least one of the first two relationships of preference is strong.

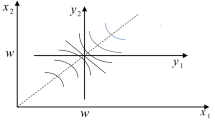

Pareto presented, in the Mathematical appendix to the French edition of the Manual (1909, 2014), individual’s preferences without assuming transitivity, even if this assumption is implied by the adoption of the ordinal utility function currently used in the Manual. Pareto presented individual’s preferences by means of a field of marginal rates of substitution. Transitivity is implied by the closed cycle condition while transitivity is not attained in case of an open cycle. Cycles are closed if the field of marginal rates of substitution is conservative (Montesano 2006).

The price-probabilities do not coincide with the probabilities if agent's preferences are state dependent. The state dependence concerns preferences on the possible outcomes, which are \( w_{e} \) and \( w_{{\bar{e}}} \), by taking into account that preferences may depend also on the corresponding events. We can write \( w_{e} = (x^{\prime},e) \) and \( w_{{\bar{e}}} = (x^{\prime\prime},\bar{e}) \), i.e. \( w_{e} \) is the amount of money \( x^{\prime} \) that the decision-maker holds with the event e and \( w_{{\bar{e}}} \) is the quantity of money \( x^{\prime\prime} \) that he holds with the event \( \bar{e} \). Preferences are not state dependent if the preference between \( w_{e} \) and \( w_{{\bar{e}}} \) depends only on the quantities \( x^{\prime},x^{\prime\prime} \), i.e. \( w_{e} \succ w_{{\bar{e}}} \) if and only if \( x^{\prime} > x^{\prime\prime} \), whatever \( e,\bar{e} \) are; preferences are state dependent if events affect preference between \( w_{e} \) and \( w_{{\bar{e}}} \), and, consequently, it may be \( w_{e} \succ w_{{\bar{e}}} \) even if \( x^{\prime} \le x^{\prime\prime} \). If the expected utility theory with objective probabilities applies and there is state dependence, so that \( U(w) = \pi_{e} u(x^{\prime},e) + \pi_{{\bar{e}}} u(x^{\prime\prime},\bar{e}) \), the marginal reservation price \( p(h_{e} |y) \) turns out to be \( p(h_{e} |y) = \frac{{\left. {\pi_{e} \frac{{\partial u(x^{\prime},e)}}{{\partial x^{\prime}}}} \right|_{{x^{\prime} = y}} }}{{\pi_{e} \left. {\frac{{\partial u(x^{\prime},e)}}{{\partial x^{\prime}}}} \right|_{{x^{\prime} = y}} + (1 - \pi_{e} )\left. {\frac{{\partial u(x^{\prime\prime},\bar{e})}}{{\partial x^{\prime\prime}}}} \right|_{{x^{\prime\prime} = y}} }} \) and differs from the probability \( \pi_{e} \) if \( \left. {\frac{{\partial u(x^{\prime},e)}}{{\partial x^{\prime}}}} \right|_{{x^{\prime} = y}} \ne \left. {\frac{{\partial u(x^{\prime\prime},\bar{e})}}{{\partial x^{\prime\prime}}}} \right|_{{x^{\prime\prime} = y}} \). The presence of state dependence makes it difficult to determine the subjective probabilities for the theory of expected utility introduced by Savage in the absence of objective probabilities. Proposals in this regard are not lacking (for example, Karni 1999).

References

Allais, M. (1953). Le comportement de l’homme rationnel devant le risque. Critique des postulates et axioms de l’école américaine. Econometrica, 21, 503–546.

Anscombe, F. J., & Aumann, R. J. (1963). A definition of subjective probability. Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 34, 199–205.

Bernoulli, D. (1738, 1954). Specimen theoriae novae de mensura sortis. Commentarii Academiae Scientiarum Imperialis Petropolitanae, 175–192. English translation: Exposition of a new theory on the measurement of risk. Econometrica 22, 23–26.

de Finetti, B. (1931). Sul significato soggettivo della probabilità. Fundamenta Mathematicae, 17, 298–329. (Warszawa).

de Finetti, B. (1937). La prévision: ses lois logiques, ses sources subjectives. Annales de l’Institut Henri Poincaré, 7, 1–68.

Debreu, G. (1959). Theory of value. New York: Wiley.

Ellsberg, D. (1961). Risk, ambiguity and the Savage axioms. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 75, 643–669.

Ellsberg, D. (2001). Risk, ambiguity and decision. New York: Routledge.

Friedman, M., & Savage, L. J. (1952). The expected-utility hypothesis and the measurability of utility. Journal of Political Economy, 60, 463–474.

Gilboa, I. (2009). Theory of decision under uncertainty. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263–292.

Kahneman, D. & Tversky, A. (2000/1984). Choices, values, and frames. In D. Kahneman & A. Tversky (Eds.), Choices, values, and frames (pp. 1–16). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (Originally published in American Psychologist 39, 341–50).

Karni, E. (1999). Elicitation of subjective probabilities when preferences are state-dependent. International Economic Review, 40, 479–486.

Klibanoff, P., Marinacci, M., & Mukerji, S. (2005). A smooth model of decision making under ambiguity. Econometrica, 73, 1849–1892.

Montesano, A. (2006). The paretian theory of ophelimity in closed and open cycles. History of Economic Ideas, 14, 77–100.

Pareto, V. (1906, 1909, 2014). Manuale di economia politica. Milano: Società editrice Libraria. Manuel d’économie politique. Paris: V. Giard & E. Brière. English translation: A. Montesano, A. Zanni, L. Bruni, J.S. Chipman & M. McLure (Eds.) Manual of political economy. A critical and variorum edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Quiggin, J. (1982). A theory of anticipated utility. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 3, 323–343.

Richter, M. K. (1966). Revealed preference theory. Econometrica, 34, 635–645.

Richter, M. K. (1971). Rational choice. In J. S. Chipman, L. Hurwicz, M. K. Richter, & H. F. Sonnenschein (Eds.), Preferences, utility, and demand (pp. 29–58). New York: Harcourt Brave Jovanovich.

Savage, J. (1954). Foundations of statistics. New York: Wiley.

Schmeidler, D. (1989). Subjective probability and expected utility without additivity. Econometrica, 57, 571–587.

Simon, H. (1957). A behavioral model of rational choice. In Models of man, social and rational: Mathematical essays on rational human behavior in a social setting. New York: Wiley.

Smith, C. A. B. (1961). Consistency in statistical inference and decision. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological), 23, 1–37.

Thaler, R. H. (2016). Behavioral economics: Past, present, and future. American Economic Review, 2016, 1577–1600.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1992). Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5, 297–323.

Tversky A., & Thaler R. H. (1990). Anomalies: Preference reversals. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 4, 201–211.

von Neumann, J., & Morgenstern, O. (1947). Theory of games and economic behavior. Princeton: Princeton University Press. (1st ed. 1944, 2nd ed. 1947, 3rd ed. 1953).

Wakker, P. P. (2010). Prospect theory for risk and ambiguity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zappia, C. (2015). Daniel Ellsberg on the Ellsberg paradox. http://www.siecon.org/online/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Zappia.pdf.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Montesano, A. On some aspects of decision theory under uncertainty: rationality, price-probabilities and the Dutch book argument. Theory Decis 87, 57–85 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-019-09695-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-019-09695-7