Abstract

The Knobe effect (Analysis 63(3):190–194, 2003a) consists in our tendency to attribute intentionality to bringing about a side effect when it is morally bad but not when it is morally good. Beebe and Buckwalter (Mind Lang 25:474–498, 2010) have demonstrated that there is an epistemic side-effect effect (ESEE): people are more inclined to attribute knowledge when the side effect is bad in Knobe-type cases. ESEE is quite robust. In this paper, I present a new explanation of ESEE. I argue that when people attribute knowledge in morally negative cases, they express a consequence-knowledge claim (knowledge that a possible consequence of an action is that harm will occur) rather than a predictive claim (knowledge that harm will actually occur). I use the omissions account (Paprzycka in Mind Lang 30(5):550–571, 2015) to explain why the consequence-knowledge claim is particularly salient in morally negative cases. Unlike the doxastic heuristic account (Alfano et al. in Monist 95(2):264–289, 2012), the omissions account can explain the persistence of ESEE in the so-called slight-chance of harm conditions. I present the results of empirical studies that test the predictions of the account. I show that ESEE occurs in Butler-type scenarios. Some of the studies involve close replications of Nadelhoffer’s (Analysis 64(3):277–284, 2004) study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Knobe (2003a, b, 2007, 2010) has discovered that people tend to claim that an agent brought about an unintended but foreseen side effect intentionally if the side effect violates a salient norm (the harm case), but they do not make this claim if the side effect complies with the norm (the help case). Beebe and Buckwalter (2010) have found that a similar effect concerns knowledge attribution in Knobe’s cases. Although all evidential factors are the same in both stories, people are more inclined to attribute knowledge to the agent in the harm case than in the help case. The epistemic side-effect effect (ESEE) is quite robust (Beebe and Jensen 2012). Just like the Knobe effect, it extends to other (epistemic) concepts (Beebe 2013; Dalbauer and Hergovich 2013) and it is not limited to English speakers (Dalbauer and Hergovich 2013).Footnote 1 The findings thus present a challenge not only to the orthodox theories of intentional action but also to the received epistemological theories.

In Sect. 1, I distinguish two strategies of explaining ESEE. The “puzzling-help” strategy is pursued by the doxastic heuristic account (DHA; Alfano et al. 2012), which is a leading explanation of ESEE. I argue that DHA (and the puzzling-help strategy in general) has problems with accounting for the persistence of ESEE in the slight-chance of harm scenarios. In Sect. 2, I propose a new explanation of ESEE, which follows the alternative “puzzling-harm” strategy. I rely on the omissions account (Paprzycka 2015), according to which there is a salient knowledge claim (concerning the knowledge of possible consequences) in the harm case. Moreover, the consequence-knowledge claim can be reasonably expressed in the form of words in which a predictive claim would be. The account explains why ESEE is preserved even if the probability of the outcome is very low (Beebe and Jensen 2012; Dalbauer and Hergovich 2013). In Sect. 3, I present the results of empirical studies that test the predictions of the account.

1 Two strategies of explaining the epistemic side-effect effect

Beebe and Buckwalter (2010) presented people with the vignettes Knobe used in his original study (2003a):

The vice-president of a company went to the chairman of the board and said, “We are thinking of starting a new program. It will help us increase profits, but [and] it will also harm [help] the environment.

The chairman of the board answered, “I don’t care at all about harming [helping] the environment. I just want to make as much profit as I can. Let’s start the new program.

They started the new program. Sure enough, the environment was harmed [helped].”

They found that people are much more inclined to judge that

(K) The chairman knew that the environment would be harmed

in the harm scenario than they are inclined to judge that he knew that the environment would be helped in the help scenario. They got a mild knowledge claim in the help case (M = .91 on a Likert scale between − 3 and 3) but a strong knowledge claim in the harm case (M = 2.25). Beebe and Jensen (2012) obtained similar results using different scales as well as different vignettes. In a forced-choice answer format, Beebe and Jensen (2012) obtained the classical Knobe-effect proportions: 68% attributions of knowledge in the harm case but only 16% in the help case. Dalbauer and Hergovich (2013) have replicated ESEE (as well as the Knobe effect) on a German-speaking population. They measured people’s agreement with the knowledge claim by means of a visual analog scale ranging from “complete disagreement” to “complete agreement.” The responses were automatically coded as a number between 1 and 100. They still obtained a statistically significant difference between the harm (M = 96.07, Sd = 15.71) and the help case (M = 87.05, Sd = 26.65).

These results are puzzling from the perspective of any received epistemological theory. It seems hard to deny that the chairman is in the same epistemic position (understood in received epistemological terms) with respect to whether the environment would be helped or harmed. He relies on the testimony of the vice-president. However, the only undeniable prediction of the received view is that people should be inclined to respond in the same way in both conditions. It is not clear that the received theories allow us to offer any more specific predictions. This opens a way for at least two main strategies of explaining ESEE.

First (“puzzling-help” strategy), one might take it that people respond correctly in attributing knowledge in the harm case and that what needs explaining are people’s responses in the help condition. One might argue that the chairman relies on the testimony of the vice-president, whom he takes to be highly reliable. One would thus predict that in both the harm and the help condition people ought to claim that the chairman knew that the environment would be harmed or helped. The problem then is why people are less inclined to attribute knowledge in the help case.

Alternatively (“puzzling-harm” strategy), one might think that people respond correctly in the help case but that the responses in the harm case need explanation. One can argue that while the chairman certainly does have some reason to believe that the environment would be helped, it is not clear that the reason is sufficient for the attribution of knowledge to the chairman. Predictions never take all factors into account. As we know from experience, lots of factors can interfere. It would be irrational to stake too much on a prediction even if it is made by an usually reliable vice-president. So, one could argue that one would expect a relatively mild assessment of knowledge about what will happen. If pressed to make a forced choice, one may even expect people to choose the claim that the chairman does not really know what will happen to the environment rather than the claim that he does know. On this strategy, what needs explaining is rather the strong attribution of knowledge in the harm case.

The leading account of ESEE is the doxastic heuristic account (DHA) due to Alfano, Beebe and Robinson (2012).Footnote 2 They present a unified account of many Knobe-type effects but I will focus on their explanation of ESEE. Their account seems to fit the “puzzling-help” strategy. They argue that all the asymmetric attributions derive from a basic asymmetry in belief attributions (Beebe 2013). The basic asymmetry is due to the fact that, in cases of norm violation, people have special reasons to reflect on the side effect and to form beliefs about it. By contrast, in cases of norm conformity, people do not have such special reasons and thus do not form beliefs about the side effects. So it is rational for people to exhibit a greater tendency to form beliefs (and to attribute beliefs) in cases of norm violation than in cases of norm conformity.

Alfano et al. thus take the harm case as not needing much explanation: people roughly respond as they should. What does need explanation is the help case. To explain why people are disinclined to attribute knowledge in the help case, they rely on the connection between knowledge and belief. Since knowledge implies belief,Footnote 3 and since they have established that it is rational for people not to attribute beliefs in the help case, people will also be disinclined to attribute knowledge in the help case by applying modus tollens.Footnote 4

One problem with DHA, and with the puzzling-help strategy in general, is that ESEE persists even in the slight-chance of harm conditions. In Knobe’s original case, the probability that the environment will be harmed may be thought to be relatively high as the vice-president asserts that the environment will be harmed. In one experiment, Beebe and Jensen (2012) have contrasted a “slight chance of harm” condition with a “very strong chance of help” condition. In the slight chance of harm case, the vice-president says: “We are sure that [the program] will help us increase profits, but there is a slight chance that it will also harm the environment.” When people were asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with the claim “The chairman knew that the new program would harm the environment” (on a Likert scale marked “strongly disagree” (− 3), “neutral” (0), and “strongly agree” (3)), they tended to agree with the claim (the mean response was 1.15). By comparison, in the strong-chance of help case, where the vice-president asserts that “there is a very strong chance that [the program] will help the environment,” the mean response was .3 (the difference is statistically significant).

According to DHA, people have good reasons to be epistemically alert in the norm violation cases, and thus to attribute beliefs and knowledge to the protagonists. But surely such attributions ought to be sensitive also to other factors. When we realize that the probability of an event is very low, it is irrational to believe that the event will occur. The fact that the event violates a norm might make us more worried about the fact that the event will occur, but it is not clear why we should believe that the event will occur. We all know that a nuclear war or the fall of a huge meteorite is probably more horrible than anything we can imagine, but this is no reason to think that it is very likely that those events will occur.

In sum, I have distinguished two strategies of explaining ESEE. On the puzzling-help strategy, one takes the harm case to be well handled by the received epistemological theories (with some possible additions such as the reasons provided by DHA). The task is then to find an explanation why the attributions of knowledge in the help case are lower than what one would expect (relative to the harm case). By contrast, the puzzling-harm strategy takes the help case to be well handled by the received epistemological theories. The task is then to explain why the attributions of knowledge in the harm case are higher than what one would expect (relative to the help case). Unfortunately, no received epistemological theory can be operationalized sufficiently to adjudicate between the two strategies. The only prediction they do make is that there should be no difference between the harm and the help case.

I have argued that the slight-chance of harm experiments pose a prima facie problem to the puzzling-help strategy and to DHA in particular. For in the slight-chance of harm condition, the received epistemological theories would not allow the knowledge attribution. At the very least then, people’s responses in the harm condition become puzzling as well. In the remainder of this paper, I develop an account that follows the alternative puzzling-harm strategy of explaining ESEE.

2 The omissions account of ESEE

So far, it has been assumed that the knowledge claim people assent to in ESEE is a predictive claim about what is going to happen. I use the omissions account of the Knobe effect (Sect. 2.1) to argue that another knowledge claim, a consequence-knowledge claim (Sect. 2.2), is particularly salient when omissions are in play, i.e. in the harm case (Sect. 2.3). ESEE can be explained if one allows that what appears to be an attribution of a predictive claim is an attribution of a consequence-knowledge claim. Moreover, because the two knowledge claims are independent of one another, the account can explain the persistence of the attribution of the knowledge claim in the slight-chance of harm experiments (Sect. 2.4).

2.1 The omissions account of the Knobe effect

The central thought of the omissions account of the Knobe effect (Paprzycka 2015) is that one can conjoin the orthodox theory of intentional action (which may include the requirement of intention for the intentionality of action, the so-called simple view, cf. Adams 1986; McCann 1986, 1991) and the normative theory of intentional omission (which requires awareness for the intentionality of omission). On that account, the troublesome attribution of intentional harming to the chairman is not an attribution of an intentional action it appears to be. Rather, it is an attribution of an intentional omission, which is linguistically expressed as if it were an intentional action.

On the normative theory of intentional omissions (Feinberg 1984; Gorr 1979; Smith 1990, 2005), an agent intentionally omits to φ if and only if (a) it is her duty to φ or she is otherwise reasonably expected to φ (the normative condition), (b) she is able to φ (the ability condition), but (c) she does not φ (the failure condition), and (d) she is awareFootnote 5 of (a), (b) and (c) (the knowledge conditionFootnote 6). The theory provides a natural explanation of the Knobe effect provided that the theory is applied to the special case of negative duties. In Knobe’s harm case, (a) the chairman has a duty not to harm the environment; (b) it is within his power not to harm the environment for it is within his power not to start the program; (c) he does harm the environment, i.e. fails to do the duty. His omission is intentional because (d) he is aware of all of this. Thus, if we apply the theory, we obtain the attribution of an intentional omission:

(O) The chairman intentionally omits (to do his duty) not to harm the environment.

There are reasons to think that the problematic intentional action attribution is a disguised form of the intentional omission attribution (O). After all, the description of the omission is cumbersome. It involves two negations, as it were: one is part of the content of the negative duty, the other is part of the concept of an omission (to omit to do something is not to do it). It might thus be tempting to cancel the two negations (for details, see Paprzycka 2015) to obtain the claim that

(A) The chairman intentionally harms the environment.

In sum, on the omissions account, in Knobe’s harm case, we have reasons to attribute an intentional omission not to harm the environment (O), the attribution of which might be expressed in a simplified way as if it were an attribution of an intentional action (A). While we have reasons not to attribute an intentional action of harming the environment (there is no intention to harm),Footnote 7 it is understandable that people do appear to make such attributions. At the same time, in the help case, there is no reason to attribute an intentional omission to the chairman (the chairman does not knowingly fail to do his duty). Likewise, there is no reason to attribute an intentional action (the chairman does not intend to help the environment).

It should be pointed out that the omissions account is presented as a rational reconstruction of the Knobe effect rather than as a psychological explanation of what goes on in people’s minds when they make the intentionality attributions (Paprzycka 2015, pp. 555–556). Moreover, it is implausible to think that people make an error when they attribute an intentional harming to the chairman instead of an intentional omission not to harm. The sheer complexity of the latter attribution puts pressure on some simplification. The error lies not in how people speak but in the distillation of the philosophical concepts from the ways people speak. The omissions account can thus be argued to be compatible with a variety of psychological accounts.

One could adapt Marr’s (1982) classic distinction of levels of investigation, to claim that the conceptual distinction between the intentional action of φ-ing and the intentional omission to φ may be implemented in different ways. On a simple implementation scheme, attributions of intentional actions of φ-ing would be made by means of claims of the form ‘x φ-s intentionally’ whereas intentional omissions (not) to φ would be attributed by means of claims of the form ‘x omits (not) to φ intentionally’. Such an implementation scheme would serve philosophical and theoretical purposes because it would be easy to read off the concepts from linguistic expressions. Arguably, however, the scheme would be highly uneconomical especially in situations that matter to us greatly. When norms with negative content are violated, we would have to use highly convoluted linguistic expressions.

Consider an alternative implementation scheme, where (a) the attributions of intentional actions of φ-ing are made by means of claims of the form ‘x φ-s intentionally’, (b) the attributions of intentional omissions to φ (when norms with positive content are violated)—by means of claims of the form ‘x omits to φ intentionally’, but (c) the attributions of intentional omissions not to φ (when norms with negative content are violated)—by means of claims of the form ‘x φs intentionally’. Moreover, the conditions of (c) attributions would be more like (b) than (a) in requiring awareness rather than intention. Such a system might look to be complex when it comes to its implementation (and to subsequent theoretical reconstruction) but it ultimately serves the economy of language.

2.2 The consequence-knowledge claim and the predictive claim

The agent will have committed an intentional omission not to do some harm (not to bring about a harmful consequence) only if both:

(1) she knew that her action might lead to some harmful consequences, and

(2) she knew what the consequence was.

Two points ought to be stressed. First, ‘might’ in (1) is justified. In particular, the operator need not be as strong as ‘will’ or ‘will in all likelihood’ or ‘will more probably than not’. When the agent has a duty not to φ and when she knows that her ψ-ing might lead to φ-ing, she also knows that in ψ-ing she might fail to do her duty. The agent should ensure (within reason)Footnote 8 that the duty is fulfilled, i.e. she is supposed to ensure that she does not φ. If she knows that there is a chance that her ψ-ing might lead to φ-ing, ceteris paribus she should ensure that she does not ψ, she should not take that chance. In other words, the intentionality of the omission not to bring about a harm does not require that the agent know that her action will (in all likelihood, more probably than not) lead to the harmful consequence. The connection is weaker. The agent will commit an intentional omission not to bring about some harmful consequences only if she knows that her action might bring them about.

Second, the agent may know that her action might lead to some harmful consequences but not know that of a specific consequence. In such a case, it seems reasonable to reserve the attribution of intentionality only to the cases of which she knew that they were among the harmful consequences. For example, Susan may know that if she switches on all her electric devices, she might overload the circuit, and thus cause the electricity in her apartment to be switched off. She may know that this may lead to harmful consequences. She may realize that her sister’s delicate fish will die if there is such a shutdown. However, she may be unaware of the fact that the fuses in the building do not work properly. Her action causes a shutdown not only in her apartment but in the whole area. As a result, Adam’s treasured fish die several buildings away. In such an event, Susan cannot be said to have killed Adam’s fish intentionally. Note that it would be natural to justify the claim that she did not do so intentionally by saying “she did not know that Adam’s fish would die”.

Indeed, the claim “she did not know that A would happen” is the form that an excuse can take. If the agent did not know that the possible harmful consequence of her action was that A would happen, she cannot be said to have brought about A intentionally. Because excuses play a vital role in our practices, it can be expected that excuse-claims can figure very prominently in our minds even if they are expressed in an abbreviated form.

On the omissions account, it is most natural to interpret the knowledge claim (K) as the negation of an excuse, i.e. as an instance of the consequence-knowledge claim (2):

-

(OK)

The chairman knew that [a possible consequence of his action was that] the environment would be harmed.

The crucial fact is that (OK) is not a prediction about what will happen to the environment. It is a claim to the effect that the agent knew what the possible harmful consequence of his action was.

The precise formulation of the predictive claim is somewhat difficult because, arguably, it is most natural to formulate it simply as (K). However, perhaps the following alternative formulations can be thought to capture the gist of the predictive claim (PK):

- (PK1):

-

The chairman knew that [it is highly probable that] the environment would be harmed

- (PK2):

-

The chairman knew that [it is more probable than not that] the environment would be harmed

- (PK3):

-

The chairman knew that [it would actually be the case that] the environment would be harmed

(Below, when I refer to the predictive claim, I do not have any one specific formulation in mind.)

It seems clear that the chairman can know for sure what the possible harmful consequence of his action is without thereby being convinced at all that the consequence will occur. It is thus possible to endorse (OK) but deny (PK). Likewise, it is possible for (PK) to be true but for (OK) to be false. This would be the case, for example, if the chairman had reasons to believe that the environment would be harmed (as part of general knowledge acquired perhaps from newspapers) but was not aware that the programs of his company would actually contribute to it.

The central thought of the omissions explanation of ESEE is that the culprit knowledge claim in the harm case (K) is not the predictive claim (PK) it appears to be. Rather the attributions of (K) in the harm case are attributions of the consequence-knowledge claim (OK), the denial of which would count as an excuse (Paprzycka 2016b, c).

2.3 The salience of the consequence-knowledge claim in the harm case

One might object that thus far the harm and the help case are fully symmetrical. After all, one could argue that also in the help case the chairman knew that:

(1) some positive consequences might ensue, and that

(2) one of the possible consequences was that the environment would be helped.

This is true. It must be pointed out, however, that the role played by the consequence-knowledge claim in the case of an omission (harm scenario) and of an action (help scenario) is very different. The knowledge of the possible consequence plays a pivotal role only for the intentionality of omissions.

On the normative theory of intentional omissions, an agent’s awareness is a mental state that is both necessary and sufficient for the intentionality of the omission. In deciding whether an omission is intentional or not, we will focus on awareness. In particular, we will focus on whether the agent was aware of the consequence that might ensue. One can thus expect the consequence-knowledge claim to be particularly salient in the cases of omissions.

On the orthodox theory of intentional action, on the other hand, the agent’s awareness of a possible consequence plays a secondary role. On the simple view of intentional action, for example, the intentionality of the action will require the agent’s intention of bringing about the consequence. Arguably, if an agent has the intention, she has the requisite knowledge: if an agent intends to φ by ψ-ing, she is aware (at least) that a possible consequence of her ψ-ing is that she will φ (Anscombe 1963; Moran 2004). However, knowledge does not suffice for intentionality. Suppose that an agent is merely aware that her action might have a certain consequence, e.g. she is aware that by standing up, she might touch the ceiling in the cockpit. Suppose further that she intends to stand up, actualizes her intention in standing up and happens to touch the ceiling. It does not follow that the agent touched the ceiling intentionally. On the standard view, she must have at least intended to touch the ceiling. One can thus expect that in the cases of actions, people will focus on intention rather than knowledge of consequences.

If the omissions account is correct that the intentionality attributions are dual (sometimes governed by the orthodox theory of intentional action while other times governed by the normative theory of intentional omissions), then people can be expected to look for different mental states in deciding about intentionality. In thinking about the intentionality of an omission, the crucial question is the question of the agent’s awareness (knowledge) among others of the possible consequence that the agent is alleged to have brought about (omitted not to bring about) intentionally. In thinking about the intentionality of the action, the crucial question is the question of the agent’s intention to bring about the possible consequence of his action. If this is right, then one would expect people’s attention to be focused on different claims in the harm case (where an omission is at issue) and in the help case (where an action is at issue). The knowledge claim in the help case does not play such a crucial role, hence it is not as salient as it is in the harm case.

In other words, the asymmetry between the harm and the help cases consists in the fact that, in the harm case, it becomes natural to interpret (K) in terms of (OK) because the harm case involves a salient intentional omission and (OK) (together with other knowledge claims, viz. awareness of the normative condition and of the ability condition) is in fact sufficient for the intentionality of the omission. By contrast, in the help case, (K) is naturally interpreted in terms of (PK) because (OK) does not play such a pivotal role for the intentionality of the action. For the purposes of a rational reconstruction of ESEE, it is sufficient to observe that (K) may stand for the consequence-knowledge claim (OK) and that there are reasons why (OK) is so prominent in the harm case. If one is interested in the explanation of the data, then one will likely view our inclination to assert (K) as an outcome of two possibly competing inclinations to assert (OK) and (PK).

It should be noted that there is no reason on the omissions account to think that other factors may not influence the salience of the knowledge claim in the help scenario. If this is so then, conceivably, one could manipulate the size of ESEE or even make it disappear altogether by making (OK) more salient in the help case.

2.4 Explanation of the slight-chance of harm experiments

As we have seen, the consequence-knowledge claim (OK) is independent of the predictive claim (PK). As long as the intentional omission is sufficiently salient, people should be inclined to assert (OK) even when they have reasons to deny (PK). In the original Knobe case, the probability that the environment will be harmed can be thought to be relatively high as the vice-president asserts that the environment will be harmed. If the above hypothesis that (K) is (OK) is right then ESEE should appear even in the case where the probability that the environment will be harmed is small.

Indeed, Beebe and Jensen (2012) have conducted such an experiment (Sect. 1). In the slight-chance of harm condition, participants tend to agree with the knowledge claim (M = 1.15), while in the strong-chance of help condition, participants’ agreement with the knowledge claim is lower (M = .3). On the omissions account, people’s heightened tendency to accept the knowledge claim in the slight-chance of harm case can be interpreted in terms of their focus on the consequence-knowledge claim, which is essential to the intentionality of the omission. This is further supported by the observation that the proportion of people who are inclined to make the knowledge attribution (K) in the slight-chance of harm condition is virtually the same as in the forced-choice study (Experiment 1; Beebe and Jensen 2012). The data presented by Beebe and Jensen (2012) show that, in the slight-chance of harm case, 70% of participants are inclined to agree with the knowledge claim to some degree while only 22% of participants are inclined to disagree with the knowledge claim.Footnote 9

In fact, in the slight chance of harm case, the principle of charity (Davidson 1984) seems to dictate that we should not interpret (K) as the false predictive claim (PK). Fortunately, there is an alternative: we can interpret (K) as the consequence-knowledge claim (OK).

Let me briefly suggest the potential of the account to explain other data.Footnote 10 In each of the cases, the matter is complex and would require more investigation. First, Turri (2014) claims to have demonstrated that the knowledge claim in the normatively negative scenario persists even though the typically required elements of justification, truth, or belief are missing.Footnote 11 This leads him to doubt that ESEE can be explained in rational terms at all. In particular, he shows that people claim that the chairman knew that the environment would be harmed even though they were told that it was not harmed. This result might be taken as evidence that people’s concept of knowledge is not factive. However, if one accepts the above explanation of ESEE, it is not surprising that people were inclined to attribute knowledge that the environment would be harmed to the chairman even though they were also told that the environment was not harmed. Their response can be understood as an attribution of the consequence-knowledge claim. After all, it is true that the chairman knew that it was a possible consequence of his action that the environment would be harmed. The fact that the environment was not harmed does not undermine the consequence-knowledge claim. Thus Turri’s experiment need not be taken as evidence that people’s concept of knowledge is not factive.

Second, ESEE has been shown to extend to other concepts such as belief (Beebe 2013) or some probability attributions (Dalbauer and Hergovich 2013). From the perspective of the omissions account these effects can be understood to be derivative from the main ESEE in virtue of the conceptual connections between knowledge and belief, on the one hand, and between belief and probability judgments, on the other. Third, Beebe and Shea (2013) have shown that the knowledge claim in the normatively negative stories tends to resist Gettierization (see also Turri 2014). They also present some evidence that the Knobification of the stories tends to trump the Gettierization effect. On the above account, this can be explained by the fact that the Gettierization of a story affects the predictive knowledge claim but not the consequence-knowledge claim. However, as mentioned, all of these findings are more subtle. In some of the studies the effect is visible, in others not. There is a clear need to investigate the matter more fully but I cannot do so here.

One might object that it is undesirable to claim that speakers mean something other than what they have said.Footnote 12 It is not clear, however, that this is true. In ordinary talk, we often use shortcuts, our expression is often not precise, sometimes we appear to contradict ourselves, we speak in haste, we make mistakes, some of which we correct, others of which we let pass (if indeed we manage to recognize them as mistakes). Various pressures (time, stress, overload) do not foster precision of expression. Moreover, natural language is full of phrases and expressions that carry a variety of different meanings. In fact, there are theories of mind and language that take charitable interpretation of a speaker’s utterance as an integral part of what the speaker says (Davidson 1984, 2003, 2005a, b). As long as there are contexts where a certain form of words will be understood to convey the right sort of content there will be no reason to make it more precise (perhaps one could appeal to Grice’s (1989) maxim of quantity in this connection). Clearly, these reasons cannot convince one that there are contexts where the form of words (K) can be used to represent (OK), but they should be sufficient to allow for such a possibility.

2.5 Summary

I have thus suggested that ESEE can be explained in terms of the conflation of two knowledge claims (the consequence-knowledge claim and the predictive claim). In the morally negative scenarios, where omissions are in play, the consequence-knowledge claim is particularly salient because the agent’s awareness of consequences is a decisive factor in settling the question of the intentionality of the omission. I have shown that the account can explain the slight chance of harm experiments. I have also argued that it has some potential to explain other data.

3 Empirical predictions and tests

One of the implications of the omissions account is that ESEE ought to persist also in the Butler-type scenarios. Butler (1978) posed the following puzzle. When a person hopes to throw a six with a regular die and succeeds, we would not say that she did so intentionally. But when she hopes to kill Smith, puts one bullet into a six-chambered gun, spins the chamber so that the bullet is allotted randomly, fires and happens to kill Smith, we would say that she killed Smith intentionally. In Butler-type scenarios, one would expect people not to accept the predictive knowledge claims. First, the probability of the outcome can be evaluated relatively precisely as (at most) one in six. Second, in Butler-type stories the testimonial evidence characteristic of Knobe-type stories is absent. On the omissions account, the Butler problem is to be explained in a similar way as the Knobe effect. In the immoral cases, there is an intentional omission not to kill Smith (see Paprzycka 2015). One would thus expect the consequence-knowledge claims to be salient in the immoral cases and, consequently, that ESEE will appear in Butler-type cases.

Three of the studies invoke Butler-type scenarios (Sects. 3.1–3.3). The fourth invokes the slight-chance versus strong-chance versions of the Knobe scenarios (Sect. 3.4).

3.1 Study 1

Study 1 was a preliminary study designed to test the main prediction of the omissions account that people will be more likely to attribute the knowledge claim in the immoral cases in Butler-type scenarios. The study largely followed the design of Nadelhoffer’s (2004) experimental study of the attributions of intentionality in Butler-type situations.

It has been pointed out (Davies 1981; Kraemer 1978; Mele and Sverdlik 1996; Ross 1978; Stiffler 1981) that the scenarios in the Butler (1978) problem are structurally different. Nadelhoffer (2004) investigated both the dimension of the moral valence of the consequences (immoral vs. neutral) as well as the structure of the action (shooting vs. throwing a die). The morally neutral shooting case involved shooting a paper target with a six-chambered gun, which had only one randomly allotted bullet in it. The immoral dice throwing case was based on a Lowe-type (Lowe 1980) scenario where throwing a six has the consequence of detonating a bomb and killing Smith. In the case of throwing dice, Nadelhoffer asked both about the intentionality of throwing a six as well as about the intentionality of bringing about the consequence (killing in the immoral case, and winning a dice game in the neutral case). He found that people are more likely to attribute intentionality in the immoral versions of all scenarios (see “Appendix”).

3.1.1 Methodology

In Study 1, the basic structure of Nadelhoffer’s study was repeated (with some minor modifications to the vignettes to make them closer to Butler’s original scenarios, see Tables 8 and 9 in the “Appendix”). ParticipantsFootnote 13 were randomly assigned to one of twelve conditions in a 2 (Immoral; Neutral) × 3 (Killing/Hitting bull’s eye; Killing/Winning; Throwing Six) × 2 (Intentionality/Knowledge) between-subject experiment.

The participants were asked to what extent they agree or disagree with an appropriate knowledge (resp. intentionality) attribution. The answers were recorded on a Likert scale from − 3 to 3, with extreme values marked “strongly disagree” and “strongly agree”, respectively. Depending on the condition, the knowledge claim had a different content:

(KnKill) Brown knew that Smith would be killed

(KnSix) Brown knew that the die would come up six

(KnBull) Brown knew that the bull’s eye would be hit

(KnWin) Brown knew that the throw would be winning.

The main prediction of the omissions account was that the knowledge claims would get a heightened response from the participants in the immoral scenarios. In the neutral scenarios, people will interpret the knowledge claim as a predictive claim and will thus tend to deny it. In the immoral scenarios, the interpretation of the knowledge claim will be influenced not only by the predictive claim but also by the consequence-knowledge claim. There will thus be a heightened tendency to ascribe the knowledge claim.

3.1.2 Results

The results for knowledge attributions are given in Table 1 (the results for intentionality attributions are given in the “Appendix”). The knowledge claims do indeed get a significantly higher response in all the immoral scenarios. In the Shooting scenarios, people tended to attribute knowledge that Smith would be killed (M = .4, Mdn = 1), but not to attribute knowledge that the bull’s eye would be hit (M = −1.1, Mdn = −2). Interestingly, in the Dice-Killing/Winning scenarios, people tended to claim that Brown knew that Smith would be killed (M = .5, Mdn = 1), but they clearly thought that Brown did not know that the throw would be winning (M = − 1.9, Mdn = − 3). In the Neutral Dice scenarios, the attributions of knowledge that the throw would be winning were roughly the same as the attributions of knowledge that the die would come up six (M = − 1.9, Mdn = − 3). In the Immoral Throwing-Six case, people were less confident of their answer. The overall judgment was negative (M = − .5, Mdn = − 1), but it was significantly heightened with respect to the Neutral Throwing-Six scenario.

3.1.3 Discussion

These findings confirm the hypothesis. In the cases of the omissions (immoral cases), the assent to the knowledge claim is a matter of balancing two claims. In the case of throwing a six, people are disinclined to assent to the predictive knowledge claim (which is shown by their responses to KnSix and KnWin in the neutral scenarios). In the case of the omission, however, this disinclination is weighed against the inclination to assent to the consequence-knowledge claim. The assent to the knowledge claim will thus be an outcome of their disinclination to accept the predictive claim and their inclination to accept consequence-knowledge claim.

It is noteworthy in this context that a substantial number of participants (approximately 40%) strongly agree or agree with the knowledge claim in the immoral scenarios. In the Immoral Shooting case, 20% of participants strongly agree (17.1% agree, 17.1% somewhat agree) that Brown knew that Smith would be killed. In the Immoral Dice case, 28.6% of participants strongly agree (14.3% agree, 11.4% somewhat agree) with that knowledge claim.

The results support the omissions account but it could be argued that they are also consistent with DHA. A DHA theorist may claim that since in the immoral scenarios people will manifest a greater tendency to form beliefs especially about what is relevant to norm violation, the heightened tendency to attribute knowledge is to be expected. The problem, as we saw, is that it is unclear why the low probability of the outcome does not to trump the attribution of knowledge. According to DHA, people will manifest a greater tendency to attribute beliefs in the immoral cases than in the neutral cases. However, given the low probability of the outcome, people ought not to be inclined to attribute knowledge in the immoral scenarios. DHA predicts that people will exhibit a greater tendency to attribute beliefs in the immoral Butler scenarios but not that they will exhibit a greater tendency to attribute knowledge. Moreover, it is difficult to explain on DHA why almost 40% of participants strongly agree or agree with the knowledge claim. Unless people are thought to commit irrational errors, one would expect the degree of agreement with the knowledge claim to be at most minimal.

By contrast, on the omissions account, two different knowledge claims are in play. On one hand, Brown knew with certainty that a possible consequence of his action was that Smith would be killed. It is thus not surprising that so many participants strongly agree or agree with the knowledge claim. They read the knowledge claim as the consequence-knowledge claim. On the other hand, the low probability of the outcome supports the claim that Brown did not know that Smith would actually be killed. The ultimate judgement is the result of balancing these two claims. People’s heightened tendency to accept the knowledge claim in the immoral cases can be explained in terms of their focus on consequence-knowledge claim.

Both explanations admit that people err, though the error is located elsewhere. On the omissions account, people assent to an imprecise shorthand formulation of the consequence-knowledge claim. Some people fail to notice that there is another interpretation of the claim. On DHA, people err in attributing the predictive knowledge claim in a low-probability situation where they ought not to make such an attribution. Study 1, however, cannot adjudicate between the two explanations.

3.2 Study 2

In Study 1, we saw an increased tendency on the part of the participants to attribute knowledge claims in the immoral Butler-type scenarios. It is arguable, as we saw, that the results could be explained by DHA, though the responses cannot be viewed as rational. In the following study, the participants were asked to justify their attribution of knowledge (or lack thereof). The main prediction of the omissions account was that the participants who attribute knowledge in the immoral cases ought to justify their responses by appeal to evidence for the consequence-knowledge claim rather than by appeal to evidence for the predictive knowledge claim. That people will tend to justify their attributions by appeal to predictive considerations is to be expected on accounts that take the culprit knowledge claim to be predictive.

3.2.1 Methodology

In Study 2, the vignettes from Study 1 were used. ParticipantsFootnote 14 were randomly assigned to one of six conditions in a 2 (Immoral; Neutral) × 3 (Killing/Hitting bull’s eye; Killing/Winning; Throwing Six) between-subject experiment.

On the first screen, the participants were asked to give a forced-choice answer to the intentionality question and the corresponding knowledge question (KnKill, KnBull, KnWin, or KnSix). On the second screen, they were then asked to justify their response to the knowledge question (the vignette was still visible and there was a reminder of their responses to the questions from the previous screen). If they chose the answer “Yes, Brown knew that Smith would be killed”, they were given three options as possible justifications:

-

(ok)

Brown was aware that a possible consequence of his action was that Smith would be killed.

-

(pk)

The chances that Smith would be killed were one in six.

-

(other)

Other (Please, explain) _____

The last option gave them an opportunity to write in an answer. If they chose the negative answer, i.e. “No, Brown didn’t know that Smith would be killed”, they were again given three options as possible justifications:

-

(ok′)

Brown wasn’t aware that a possible consequence of his action was that Smith would be killed.

-

(pk)

The chances that Smith would be killed were one in six.

-

(other)

Other (Please, explain) _____

The justifications varied depending on the scenario in that the underlined content of the knowledge claim replaced the underlined text in the responses.

The predictions were again that, in the immoral scenarios, there will be a greater tendency on the part of the participants to ascent to the intentionality and to the knowledge claim. But the main prediction was that those participants who agree with the knowledge claim in the immoral scenarios will tend to indicate (ok) as their justification for the claim, whereas those participants who disagree with the knowledge claim will tend to indicate (pk) as their justification for the claim.

3.2.2 Results

Knowledge attributions in Study 2 are presented in Table 2 (see the “Appendix” for intentionality attributions). In all scenarios, most participants denied the knowledge claims. However, the percentage of people who attributed knowledge to Brown was significantly higher in the immoral cases than in the neutral cases.

Moreover, in the immoral cases those participants who were inclined to ascribe knowledge to Brown, predominantly cited awareness of consequences (ok) as the main justification (see Table 3). By contrast, those participants who were inclined not to ascribe knowledge to Brown predominantly cited the predictive consideration (pk). In fact, the pattern of responses to (ok) seems to be responsible for the overall pattern of knowledge attribution, while the pattern of responses to (pk) seems to be responsible for the overall pattern of knowledge denial (Cramer’s V = .762).

It is interesting that a substantial number (19, i.e. 26%) of participants in the Neutral Shooting scenario chose the optional response and provided their own justifications for knowledge denial. Most of the participants thought that Brown did not know that the bull’s eye would be hit because there was no information how good a shot Brown is.Footnote 15 It can be argued that these responses support the interpretation of the knowledge claim in its predictive interpretation. What is relevant to knowing whether the bull’s eye would actually be hit, is not only the probability that the bullet will fire (which was a factor that participants could select as a justification) but also Brown’s skills as a shooter (which were not mentioned in the story). It is interesting though that all the participants in the Immoral Shooting scenario who claimed that Brown did not know that Smith would be killed appealed to the predictive considerations provided (i.e. one-in-six probability) and none of them felt the need to appeal to Brown’s skill.

3.2.3 Discussion

The results confirm the predictions of the omissions account. First, there is a significantly higher percentage of participants who are willing to ascribe knowledge to Brown in the immoral cases. Second, those participants who were inclined to ascribe knowledge to Brown in the immoral cases, predominantly cited the awareness of consequences (ok) as the main justification. Those participants who were inclined not to ascribe knowledge to Brown, predominantly cited the predictive consideration (pk).

One could raise several objections to the design of the justificatory options.Footnote 16 One could claim that the participants were given an almost forced-choice option where the evidence for the predictive claim (the probability that Smith would be killed is one in six) seemed to speak against rather than for the truth of the predictive claim. One could argue that this alone could incline people to select the only other laid-out option, which was (ok). In response, at least two points should be raised. First, it is difficult to see what the appropriate formulation of (pk) ought to be. It was thought that if someone believes that the 1/6 probability is high enough to attribute a knowledge claim, such a person would have no problem in choosing (pk). Second, it must be stressed that in order to address problems with the formulation of the laid-out justificatory options, the design of the answers was not forced-choice. People who felt that they attributed (or denied) knowledge for other reasons did have the option to choose “other” and write in an explanation. So it was not the case that since (pk) was poorly formulated participants had to choose (ok). Of course, one could think that participants are lazy. One could argue that once they have two laid-out options to choose from, they will choose one or the other rather than bothering to write a long explanation even if the laid-out options distort what they had actually thought. The study, however, gives reasons to be skeptical of the validity of such an objection. First of all, someone who thought that none of the options captured the justification could have chosen “other” and not bothered to write in an explanation. More importantly, the above study actually provides positive evidence for the fact that participants do not always choose one of the laid-out options. They do bother to write in their own explanations. In the Neutral-Shooting scenario 19 people (almost 27%) chose the third “other” option. Moreover, they wrote justifications, which were highly reasonable.

One may also worry that the formulation of (ok) and (pk) was not parallel. It would have been if (pk) were formulated as (pka) “Brown was aware that the chances that Smith would be killed were one in six”. One might think that this formulation is better because it emphasizes what Brown thought rather than a fact. However, it is arguable that in the context of the story the most natural way of interpreting such a fact is in terms of the agent’s epistemic uptake of it. On the other hand, the problem with (pka) is that it seems to focus attention on the exact probability measure rather than on the fact that the probability was relatively low. One can see participants denying (pka) just because they may think that the story does not give any evidence as to whether Brown knew the math. Again, it ought to be stressed that the participants had the option of choosing the open justification.

It must be admitted, however, that the formulation of the justificatory options is potentially problematic. To circumvent the problems, a follow-up study (Study 3) was carried out.

3.3 Study 3

The main purpose of the study was to give the participants an opportunity to enter their own justifications.Footnote 17 The justifications were then analyzed by experts to decide which of the interpretations (predictive or consequence) they fit better.

3.3.1 Methodology

The participantsFootnote 18 were randomly assigned to one of two groups: Immoral-Dice-Kill and Neutral-Dice-Win. Only two out of the six conditions of Study 2 were tested. The main purpose of the study was to see whether or not the choice of awareness of consequence as the justification for knowledge attributions in Study 2 was an artifact of the experimental design of the study.

As in Study 2, the participants saw the story on the first screen, where they were asked the intentionality question and the knowledge question. The answers were also entered in a forced-choice format. On the second screen, with the story still visible but with no possibility of going back, they were given the instruction “Please, take a few moments to explain why you thought that Brown knew [didn’t know] that Smith would be killed [the throw would be winning]”.

The participants’ justifications were presented to a group of 9 research assistants (doctoral students and Assistant Professors in philosophy). The experts were provided with the stories, the participants’ answers to the knowledge question, and with the justifications provided by the participants. They were instructed to classify the justifications as indicating the predictive interpretation (P), the consequence interpretation (Q), or both interpretations (B) of the knowledge claim. In addition, the experts could say that they cannot decide (N), that the answer should be disqualified (D), and they were also encouraged to propose new interpretations (o).

The prediction was that most justifications of the participants who ascribe knowledge in the immoral scenario will be classified as indicating the consequence interpretation. It was further predicted that most of the justifications of the participants who deny knowledge in the neutral and in the immoral scenario will be classified as indicating the predictive interpretation.

3.3.2 Results

The difference in knowledge attribution between the two groups is statistically significant: χ2(1, N = 155) = 57.799; p < .0001 (the intentionality attributions are given in the “Appendix”). Despite the fact that the forced-choice design was used, the results are remarkably consistent with Study 2. More than a half (57.5%) of participants in the Immoral Dice case claimed that Brown knew that Smith would be killed (in comparison to 45.3% in Study 2). In both studies, almost nobody claimed that Brown knew that the throw would be winning in the Neutral Dice case. In Study 3, the one person who selected the positive answer recounted it in the justification; interestingly, the person thought that the question asked whether the throw could be winning.

The experts’ classifications of the justifications in the knowledge denial cases were rather uniform. Experts differed, sometimes quite substantially, in how they classified the justifications in the knowledge attribution cases. Table 4 presents the majority expert verdicts for both groups.

It is pretty clear that most justifications for denials of knowledge in the Immoral Dice case and in the Neutral Dice case support the predictive interpretation of the knowledge claim. Experts were unanimous on 11 (32.4%) justifications for knowledge denial in the Immoral Dice case and on 28 (37.3%) justifications in the Neutral Dice case. In the case of knowledge denials, the majority (5 or more) experts agreed on 94.1% of justifications in the Immoral Dice case and on 97.3% of justifications in the Neutral Dice case.

In the case of knowledge attributions (Immoral Dice), on the other hand, the experts were not unanimous on any justification. Most experts agreed only on 27 (58.7%) justifications. However, among those justifications that most experts agreed on, there were 24 justifications that were classified as indicating a consequence interpretation (7 experts agreed on 10 justifications, 6 agreed on 12 justifications).

It is striking that there were substantial disagreements among the experts. While the consequence interpretation was thought to be dominant by most (7) of the experts, they differed with respect to the degree of its dominance. Moreover, the remaining two experts considered other interpretations to dominate: one expert thought that most justifications indicated the predictive interpretation, while the other thought that most justifications indicated both interpretations.

3.3.3 Discussion

These results present a further confirmation for the significant impact of the consequence interpretation of the knowledge claim attributed in the Immoral Dice scenario. It is pretty clear that the predictive interpretation determines the knowledge denials in both cases. Knowledge attributions are perhaps not so clearly determined by the awareness of consequences but they are influenced by that factor to a substantial degree.

It is noteworthy, however, that there were substantial disagreements in the interpretation of the justifications for knowledge attribution in the Immoral Dice case. The experts were not unanimous on any single justification. Most experts agreed that 24 (52.2%) justifications support the consequence interpretation (out of 27, i.e. 58.7%, justifications they agreed on). Here are four examples of justifications that most experts agreed indicated a consequence interpretation:

Irrespective of the dice throw, Brown had the bomb, the lens, the camera working, and the dice, so he knew what a ‘6’ would mean.

He knew that a six-dotted image on the lens of the camera would cause the bomb to explode and kill Smith.

He knew that throwing a six would detonate the bomb.

If a bomb is detonating in the building that he knows Smith is in, he should be aware of Smith dying.

By contrast, there were only two justifications that most experts judged to indicate a predictive justification, for example:

He knew that there was a chance of the bomb killing Smith.

Interestingly, a justification that I would consider to be a model justification for the consequence interpretation was not among the justifications that most experts agreed on. Here is the justification:

Brown may not have been able to predict what the die would land on, but he knew that the result of it landing on 6 would lead to Smith being killed because it would cause the building to explode while Smith was in the building. He threw the die knowing that there was a 1/6 chance of Smith certainly being killed.

Six experts thought that it indicated the consequence interpretation, one expert thought that it indicated the predictive interpretation and two experts thought that it indicated both interpretations. Part of the problem is that predictive considerations are mentioned in the justification, though they are explicitly discounted as a reason for upholding the knowledge claim. Some experts may have thought that a predictive interpretation is in play if the justification takes predictive factors into account. Other experts may have thought that a predictive interpretation is not in play if the justification considers predictive factors but discounts them. Indeed, many experts said that the task of sorting the justifications was harder than they had initially thought.

However, the results constitute evidence against the claim that participants who attribute knowledge in the immoral scenarios always have only the predictive claim in mind. In other words, the results support the view that we need to consider alternative interpretations of the knowledge claim to account for ESEE.

3.4 Study 4

The final study was conducted in the experimental paradigm of Study 2 but with a version of Knobe-like vignettes. The main motivation was to see whether participants will also appeal to awareness of consequences in their justifications of knowledge attributions in Knobe-type rather than Butler-type stories. Slight-chance and strong-chance scenarios were used since the predictive claim is implausible in the first type of scenarios.

3.4.1 Methodology

The same sorts of questions as in Study 2 were asked, but the slight-chance and the strong-chance of harm/help vignettes (see Beebe and Jensen 2012) were used. Knobe’s story was given but the vice-president said of the program “It will help us increase profits. However/Moreover, there is a slight [very strong] chance that it will also harm/help the environment.”

ParticipantsFootnote 19 were randomly assigned to one of four conditions in a 2 (Harm; Help) × 2 (Slight-Chance; Strong-Chance) between-subject experiment. On the first screen, the participants were asked to give a forced-choice answer to the intentionality question (Did the chairman harm/help the environment intentionally?) and the knowledge question (Did the chairman know that the environment would be harmed/helped?). They were then asked to justify the latter response. If they chose the answer “Yes, the chairman knew that the environment would be harmed/helped” they were given three options as possible justifications:

-

(ok)

The chairman was aware that a possible consequence of his action was that the environment would be harmed/helped.

-

(pk)

There was a slight [very strong] chance that the environment would be harmed/helped.

-

(other)

Other (Please, explain) _____

If they chose the negative answer, i.e. “No, the chairman didn’t know that the environment would be harmed/helped”, they were again given three options as possible justifications:

-

(ok′)

The chairman wasn’t aware that a possible consequence of his action was that the environment would be harmed/helped.

-

(pk′)

There was only a slight [very strong] chance that the environment would be harmed/helped.

-

(other)

Other (Please, explain) _____

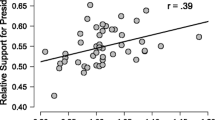

Based on previous studies (Beebe and Buckwalter 2010; Beebe and Jensen 2012), it could be expected that the statistical difference in the knowledge attributions between the slight-chance of harm and the strong-chance of help scenarios (Beebe and Jensen 2012) would be revealed in the forced-choice paradigm as well. The predictions of the omissions account and DHA for these scenarios are somewhat different. Both accounts predict that ESEE will occur. According to the omissions account, the presence of ESEE ought to be particularly strong between the slight-chance of harm and the slight-chance of help conditions. This is because in those conditions people ought to be disinclined to accept the predictive claims but they ought to be inclined to accept consequence-knowledge claim in the harm condition. In the strong chance scenarios, on the other hand, people could be expected to accept the predictive claims as well. So while one may expect a difference between the harm and the help conditions in the strong-chance scenarios, it should be smaller than the difference between those conditions in the slight-chance scenarios.

According to DHA, on the other hand, the reverse difference in the magnitude of ESEE is to be expected. People ought to be more inclined to attribute beliefs in the harm conditions than in the help conditions. However, in the strong-chance of harm condition, the asymmetry in belief attributions can be expected to be revealed also in an asymmetry in knowledge attributions. In the case of the slight-chance scenarios, on the other hand, the asymmetry in belief attributions ought not to be revealed in an asymmetry in knowledge attributions (because the slight chance of the effect constitutes a prima facie evidence against the justification of the belief).

As far as the justifications are concerned, the omissions account predicts that the knowledge attribution would be justified by awareness of consequences (ok) in the harm conditions (especially in the slight chance of harm condition) while knowledge denials as well as knowledge attributions in the help scenarios would be justified by predictive considerations (pk). According to accounts that take the knowledge claim to be predictive (such as DHA), predictive considerations ought to be cited as justification.

3.4.2 Results

For knowledge attributions, the only significant (p < .001) differences are between the harm and the help condition in the slight-chance scenarios.Footnote 20 There was no statistical difference between the slight-chance of harm condition and the strong-chance of help condition (χ2(1, N=151) = .034, p = .85). The expectation to find the difference Beebe and Jensen (2012) found (using Likert-scale answers) between the slight-chance of harm and the strong-chance of help condition was thus also not met (Table 5).

Participants tend to justify the attributions of knowledge by appeal to awareness of consequences rather than by appeal to predictive considerations. Knowledge denials, though fewer, tended to be justified by appeal to predictive considerations (see Table 6). The pattern of responses to (ok) seems to be responsible for the overall pattern of knowledge attribution, while the pattern of responses to (pk) seems to be responsible for the overall pattern of knowledge denial (Cramer’s V = .508).

3.4.3 Discussion

The results only partially support the omissions account. The main predictions are met. First, ESEE is particularly strong in the slight chance scenarios (in fact this is the only statistically significant difference between the harm and the help condition). Second, people tend to justify their attribution of knowledge in the harm scenario by appeal to awareness of consequences (ok) rather than predictive considerations (pk). They also tend to justify knowledge denials by appeal to predictive considerations (pk).

What is unexpected on the omissions account is that people tend to justify their attributions of knowledge in the help cases by appeal to awareness of consequences rather than to predictive considerations. On the omissions account, in the help scenario, there is no omission and thus no reason for the consequence of the action to be so salient. It might be that other factors in the stories, perhaps the explicit mention of chances, make the consequence salient. This would need to be investigated further.

It should be pointed out, however, that the results are even more unexpected for DHA. I have mentioned that the omissions account predicts that the magnitude of ESEE will be greater for the slight-chance conditions than for the strong-chance conditions while the reverse effect is to be expected on DHA. On DHA, one would expect ESEE to appear in its clearest form in the strong-chance scenarios. In those scenarios, one would expect there to be a basic asymmetry in the attribution of beliefs. Moreover, because the strong-chance scenarios provide the chairman with very good reasons for the beliefs, one would expect the asymmetry to be present in knowledge attributions. Because the slight-chance scenarios do not provide the chairman with good reasons for the beliefs, one would not expect a high attribution of knowledge in the harm case. The fact that no statistically significant difference was found in the strong-chance scenarios but that it was found in the slight-chance scenarios is thus a prima facie problem for the account.

That there was no statistically significant difference between the strong-chance of harm and the strong-chance of help conditions is surprising also given previous research. In Beebe and Jensen’s (2012) forced-choice study, the difference between the harm and the help condition was enormous (68% of participants attributed knowledge in the harm case, 16% in the help case). Of course, they used standard Knobe vignettes, which do not mention chance (slight or strong). Arguably, however, the strong-chance vignettes are closer to Knobe’s original vignettes than the slight-chance vignettes. Finally, what is perhaps most surprising is the number of people who are willing to attribute knowledge that the environment would be helped in the slight-chance of help condition. When the vice-president tells the chairman that the environment will be helped, only 16% of participants attribute knowledge to the chairman (Beebe and Jensen 2012). When the vice-president tells the chairman that there is a slight chance that the environment will be helped, 56% of participants say that the chairman knew that the environment would be helped. An analogous difference (though smaller) is observed between the knowledge attributions in Beebe and Jensen’s (2012) standard harm group where 68% of participants ascribe knowledge, and in the slight-chance of harm group (Study 4) where 83% of participants ascribe knowledge. What prima facie calls for explanation is why people are more inclined to attribute knowledge in the slight-chance conditions (both help and harm) than in conditions where the respective chances are not mentioned.

Perhaps the justifications gathered can throw some light on these peculiar results. Approximately 20% of participants marked predictive considerations (pk) as their justification of the knowledge attribution in the help scenarios both in the slight-chance (20.5%) and in the strong-chance (22.2%) conditions. This is very close to Beebe and Jensen’s (2012) forced-choice results for Knobe’s original vignettes, where 16% of participants attributed knowledge in the help case. Perhaps the reason why the knowledge attributions were so high in both (slight-chance and strong-chance) help scenarios is to be accounted for by people’s assent to awareness of consequences (ok). The omissions account does not provide an explanation why this was the case. It is possible that the consequence-knowledge claim was made more salient by the slight-chance/strong-chance vignettes. This would require further systematic study, however.

3.5 Summary

The main predictions of the omissions account have been confirmed. As expected, ESEE is visible in the Butler-type scenarios. There is a statistically significant difference in the attribution of the knowledge claim in the immoral cases in comparison to the neutral cases (both when a Likert scale is used to record responses in Study 1, as well as in the forced-choice paradigm in Studies 2 and 3). Moreover, as predicted, people were inclined to indicate the consequence-knowledge claim as a justification of the knowledge claim in the morally negative scenarios (Studies 2, 3, and 4). At the same time, the predictive claim appears to be responsible for the denial of knowledge in the morally negative as well as the morally neutral scenarios (Studies 2, 3, and 4).

What was not expected on the omissions account is that the consequence-knowledge claim appears to be responsible for the attribution of knowledge also in the morally positive scenarios (Study 4). This result is not expected on the omissions account but it is consistent with it. The consequence-knowledge claim is true both in the morally negative as well as in the morally neutral or positive cases. According to the omissions account, ESEE arises because, in the morally negative cases where omissions are in play, the consequence-knowledge claim is particularly salient since it accounts for the intentionality of the omission. This is consistent, however, with the possibility that other factors may increase the salience of the consequence-knowledge claim in the morally neutral or positive cases.

4 Conclusion

I have argued that to explain ESEE, we should drop the assumption that the knowledge claim people assent to in the immoral cases is a predictive claim about what is going to happen. What appears to be an attribution of a predictive claim (knowledge that p) is an attribution of a consequence-knowledge claim (knowledge that a possible consequence of one’s action is that p). I have used the omissions account of the Knobe effect to argue that the consequence-knowledge claim is particularly salient when omissions are in play, i.e. in the harm case. The consequence-knowledge claim is decisive in determining the intentionality of the omission. This explains why the knowledge claim tends to be particularly resilient in morally negative scenarios, even when the grounds for making the predictive knowledge claim are missing.

The predictions generated by the omissions account were largely confirmed in the empirical studies. ESEE persists in the Butler-type scenarios. Moreover, people who attribute the problematic knowledge claim (both in Butler-type scenarios and in the slight-chance of harm scenarios) justify it predominantly by pointing to the awareness of consequences. In Study 4, contrary to the predictions of the omissions account, the knowledge claim was justified by appeal to knowledge of consequences also in the morally positive cases. This can perhaps be explained by the fact that other factors make the claim salient. Indeed, one direction for further research is that by increasing the salience of the consequence-knowledge claim also in the morally neutral or positive scenarios, one could remove or decrease the asymmetry in the knowledge attributions between the harm and the help cases.

Let me end with two disclaimers. First, the explanation of ESEE in terms of the conflation of two knowledge claims (the consequence-knowledge claim and the predictive claim) has been given a theoretical underpinning in the omissions account. However, it ought to be stressed that the explanation is not wedded to the omissions account. It can be accepted on its own. What the omissions account provides is a theoretical reason for thinking that the consequence-knowledge claim is very prominent in the morally negative cases. Second, I have begun by distinguishing two explanatory strategies. DHA follows the puzzling-help strategy, while I have pursed the puzzling-harm strategy. However, the strategies need not be seen to be exclusive. It is possible that to fully account for the data, both strategies ought to be pursued.

Notes

Robinson et al. (2015), who think of themselves as supplementing DHA, give the following abbreviated description of the account: “…people tend to attribute relevant beliefs to agents who violate a norm but tend not to attribute congruent beliefs to agents who act in accordance with the same norm. Then, on the basis of these asymmetric belief-attributions, participants proceed to attribute various other states asymmetrically. Belief, they contend, is conceptually prior to all other psychological attributes that exhibit the side-effect effect: in order to[,] intend, know, desire, remember, be I favour of, etc. φ, one must believe that φ” (p. 179).

It has been argued that the knowledge condition rather than the intention condition is required for the intentionality of omissions on the normative account thereof (see Paprzycka 2015, 2016a; for contrary arguments on other accounts of omissions, see e.g. Clarke 2010, 2012a, b, 2014; Zimmerman 1981).

Of course, there are theorists of intentional action that will disagree (e.g.: Bratman 1987; Chisholm 1976; Ginet 1990; Harman 1976; Wilson 1989; see also Bentham 1988 [1781]; Sidgwick 1907 [1874]). However, the omissions account assumes a standard account of intentional action (including the simple view, cf. Adams 1986; McCann 1986, 1991), on which an intention to φ is necessary for the intentional action of φ-ing.

We should be cautious here. One might argue that the best way to ensure that one does not harm others is not to do anything. We know that there is a chance that we might cause an accident if we drive a car and not notice someone, for example. However, it would be unreasonable to expect people not to drive cars. Usually, the standard adopted concerns what a reasonable person should do and can foresee.

In the strong-chance of help scenario, 46% of participants are inclined to agree with the knowledge claim to some degree and 40% of participants are inclined to disagree with the knowledge claim. The percentages should not be taken as indicative of what a forced-choice study might show. Study 4 demonstrates this point very vividly.

This is merely to indicate the explanatory potential of the account. In particular, I do not argue that other explanations of the phenomena are not possible. In many cases, the explanations are available though they will be different.

Turri’s experiment that ESEE persists when justification is absent shows what the slight-chance of harm experiments demonstrate. His experiment that ESEE persists when belief is absent can be questioned because of the operationalization of belief he chooses.

I want to thank an anonymous reviewer for raising this point.

There were 431 participants (35–37 per group) recruited by Clickworker (compensation ca. €.40): 247 females, 183 males, 1 person chose not to answer; 91.6% were native speakers; the majority (84.4%) had a college or university education; the average age was 36 (median: 35); 71% had no philosophy courses.

The 472 participants (73–90 per group) were recruited by Prolific (compensation of ca. £.45): 265 females, 205 males, 2 persons chose not to answer; 98.9% were native speakers; the majority (79.2%) had college or university education; the average age was 36 (median: 35); 82% had no philosophy courses.

The subjects’ responses were analyzed independently by 6 competent judges (graduate students) who were instructed to categorize the responses in any way they saw fit and to count the number of responses that fall into each category. While the analyses differed from one another, most judges tended to think that the majority of the participants appealed to the shooter’s ability sometimes in combination with other factors (such as the lack of knowledge whether the bullet would be fired).

I want to thank both anonymous reviewers for raising many of the objections.

I want to thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting the idea of this study.

There were 155 participants (75–80 per group) recruited by Prolific (compensation ca. €.80): 84 females, 69 males, 2 persons chose not to answer; 98.7% were native speakers; the majority (83.2%) had college or university education; the average age was 33 (median: 30); 72.3% had no philosophy courses. One participant was disqualified for failing to provide a justification.

There were 300 participants (72–76 per group) recruited by Prolific (compensation of ca. £.45): 179 females, 117 males, 4 persons chose not to answer; 99.3% were native speakers; the majority (77.3%) had college or university education; the average age was 39 (median: 33); 77% had no philosophy courses.

In both scenarios, the differences for the intentionality attributions between the harm and the help condition were statistically significant: χ2(1, N=149) = 76.43, p < .0001, in the slight-chance scenarios; χ2(1, N=147) = 82.82, p < .0001, in the strong-chance scenarios. The great majority attributed intentionality in the harm scenarios: 72.4% (55) in the slight-chance condition; 80% (60) in the strong-chance condition. The great minority did so in the help scenarios: 2.7% (2) in the slight-chance condition; 5.6% (4) in the strong-chance condition.

References

Adams, F. (1986). Intention and intentional action: The simple view. Mind and Language, 1, 281–301.