Abstract

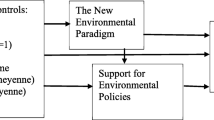

Effectively addressing environmental challenges such as climate change will require adopting policy measures that have some impact on collective human behavior. The present research examined attitudes toward different environmental policies, specifically focusing on the role of perceived justice. Justice was measured in two ways: as an assessment of the fairness of a particular policy and as a general tendency to endorse statements related to environmental justice. Because justice judgments can be context specific, policies were presented in four conditions, in a 2 × 2 design manipulating the type of impact described, ecological or societal, and the level of focus, individual or collective. The roles of political ideology and environmentalism were also investigated. Results from an online sample of 162 US residents showed that non-coercive policies, overall, were rated as more acceptable. Environmental justice statements were strongly endorsed, and justice in both its specific and general forms was a determinant of policy acceptance. In particular, ratings of the fairness of specific policies were a stronger determinant of acceptability than perceived effectiveness of the policy. Type of impact had little effect, but policies tended to be rated as more acceptable when they were framed in terms of the collective rather than the individual. Although a liberal ideology was associated with acceptance of environmental policies in general and with endorsement of environmental justice, controlling for endorsement of environmental justice eliminated the effect of political ideology in most, but not all, cases. Implications for policy support are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

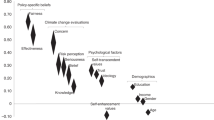

A principal components analysis of acceptability ratings, conducted to look for underlying dimensions, identified two factors with eigenvalues over 1.0, explaining 56.4% of variance. The first factor loaded on all the policies except Information and Encourage and the second loaded on those two. This seems to reflect the important distinction between “push” and “pull” policies, but could also be interpreted as distinguishing between policies that require the exercise of governmental power versus those that could be easily undertaken by a nonprofit group.

A principal components analysis of the justice principles identified two factors with eigenvalues over 1.0, explaining 57.6% of the variance. However, they were not easily interpretable. The first factor explained most of the variance and loaded on all the items, most strongly with “everyone should bear their share of the costs” and “people should buy and use less.” Factor scores were positively correlated with liberalism and environmentalism. This factor may emphasize the need to sacrifice to protect the environment. The second factor loaded most strongly on “everyone is entitled to strive for a comfortable standard of living” and “environmental protection should be the responsibility of business”, but was also high on individual responsibility. There were no significant correlations between scores on this factor and other variables measured.

References

Bertolotti, M., & Catellani, P. (2014). Effects of message framing in policy communication on climate change. European Journal of Social Psychology, 44(5), 474–486.

Brickman, P., Folger, R., Goode, E., & Schul, Y. (1981). Microjustice and macrojustice. In M. J. Lerner & S. C. Lerner (Eds.), The justice motive in social behavior (pp. 173–202). New York: Plenum.

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. (2011). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 3–5.

Chaplin, J. (2016). The global greening of religion. Palgrave Communications, 2, 16047. https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2016.47.

Clayton, S. (1998). Preference for macrojustice versus microjustice in environmental decisions. Environment and Behavior, 30, 162–183.

Clayton, S., Kals, E., & Feygina, I. (2016). Justice and environmental sustainability. In C. Sabbagh & M. Schmitt (Eds.), Handbook of social justice theory and research (pp. 369–386). New York: Springer.

Clayton, S., Koehn, A., & Grover, E. (2013). Making sense of the senseless: Justice, identity, and the framing of environmental crises. Social Justice Research, 26, 301–319.

Clayton, S., & Opotow, S. (1994). Green justice: Conceptions of fairness and the natural world. Journal of Social Issues, 50(3), 1–11.

Clayton, S., & Opotow, S. (2003). Justice and identity: Changing perspectives on what is fair. Personality and social psychology review, 7(4), 298–310.

de Groot, J. I., & Schuitema, G. (2012). How to make the unpopular popular? Policy characteristics, social norms and the acceptability of environmental policies. Environmental Science & Policy, 19, 100–107.

Deutsch, M. (1975). Equity, equality, and need: What determines which value will be used as the basis for distributive justice? Journal of Social Issues, 31(3), 137–179.

Devine-Wright, P. (2013). Explaining “NIMBY” objections to a power line: The role of personal, place attachment and project-related factors. Environment and Behavior, 45, 761–781.

Dickinson, J. L., McLeod, P., Bloomfield, R., & Allred, S. (2016). Which moral foundations predict willingness to make lifestyle changes to avert climate change in the USA? PLoS ONE, 11(10), e0163852.

Dreyer, S. J., & Walker, I. (2013). Acceptance and support of the Australian carbon policy. Social Justice Research, 26, 343–362.

Eriksson, L., Garvill, J., & Nordlund, A. (2008). Acceptability of single and combined transport policy measures: The importance of environmental and policy specific beliefs. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 42, 1117–1128.

Feinberg, M., & Willer, R. (2013). The moral roots of environmental attitudes. Psychological Science, 24, 56–62.

Feygina, I., Jost, J. T., & Goldsmith, R. (2010). System justification, the denial of global warming, and the possibility of “system-sanctioned change”. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 326–338.

Harring, N. (2016). Reward or punish? Understanding preferences toward economic or regulatory instruments in a cross-national perspective. Political Studies, 64, 573–592.

Hart, P. S., & Nisbet, E. C. (2012). Boomerang effects in science communication: How motivated reasoning and identity cues amplify opinion polarization about climate mitigation policies. Communication Research, 39(6), 701–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650211416646.

Jacoby, W. G. (2000). Issue framing and public opinion on government spending. American Journal of Political Science, 44, 750–767.

Kim, S., & Shin, W. (2017). Understanding American and Korean students’ support for pro-environmental tax policy: The application of the value-belief-norm theory of environmentalism. Environmental Communication, 11, 311–331.

Lange, A., Vogt, C., & Ziegler, A. (2007). On the importance of equity in international climate policy: An empirical analysis. Energy Economics, 29, 545–562.

Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E., Roser-Renouf, C., Feinberg, G., & Rosenthal, S. (2016). Politics and global warming, Spring 2016. New Haven, CT: Yale University and George Mason University, Yale Program on Climate Change Communication.

Lerner, M. J. (1980). The belief in a just world: A fundamental delusion. New York: Plenum Press.

Lerner, M. J., & Clayton, S. D. (2011). Justice and self-interest: Two fundamental motives. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lu, H., & Schuldt, J. (2016). Compassion for climate change victims and support for mitigation policy. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 45, 192–200.

Lubell, M., Zahran, S., & Vedlitz, A. (2007). Collective action and citizen responses to global warming. Political Behavior, 29(3), 391–413.

Lukasiewicz, A., Syme, G. J., Bowmer, K. H., & Davidson, P. (2013). Is the environment getting its fair share? An analysis of the Australian water reform process using a social justice framework. Social Justice Research, 26, 231–252.

McCright, A. M., & Dunlap, R. E. (2011). The politicization of climate change and polarization in the American public’s views of global warming, 2001–2010. The Sociological Quarterly, 52(2), 155–194.

Montada, L., & Kals, E. (1995). Perceived justice of ecological policy and proenvironmental commitments. Social Justice Research, 8(4), 305–327.

Montada, L., & Kals, E. (2000). Political implications of psychological research on ecological justice and proenvironmental behaviour. International Journal of Psychology, 35(2), 168–176.

Myers, T. A., Nisbet, M. C., Maibach, E. W., & Leiserowitz, A. A. (2012). A public health frame arouses hopeful emotions about climate change. Climatic Change, 113(3–4), 1105–1112.

Opotow, S. (1994). Predicting protection: Scope of justice and the natural world. Journal of Social Issues, 50, 49–64.

Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development. (2002). Towards sustainable household consumption? Trends and policies in OECD countries. Paris: OECD. http://www.keepeek.com/Digital-Asset-Management/oecd/environment/towards-sustainable-household-consumption_9789264175068-en#page1. Accessed January 29, 2018.

Parkhill, K., Demski, C., Butler, C., Spence, A., & Pigeon, N. (2013). Transforming the UK energy system: Public values, attitudes, and acceptability—Synthesis report. London: UKERC. http://psych.cf.ac.uk/understandingrisk/docs/SYNTHESIS%20FINAL%20SP.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2018.

Pew Research Center. (2016). The public’s policy priorities for 2016. Retrieved November, 2016 from http://www.people-press.org/2016/01/22/budget-deficit-slips-as-public-priority/1-21-2016_06/.

Sacchi, S., Riva, P., Brambilla, M., & Grasso, M. (2014). Moral reasoning and climate change mitigation: The deontological reaction toward the market-based approach. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 38, 252–261.

Shormeman-Ouimet, E., & Kopnina, H. (2016). Culture and conservation: Beyond anthropocentrism. New York: Routledge.

Steg, L., Dreijerink, L., & Abrahamse, W. (2006). Why are energy policies acceptable and effective? Environment and Behavior, 38(1), 92–111.

Stern, P. C. (2000). New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 407–424.

Syme, G., & Nancarrow, B. (2012). Justice and the allocation of natural resources. In S. Clayton (Ed.), Handbook of environmental and conservation psychology (pp. 93–112). New York: Oxford University Press.

Villar, A., & Krosnick, J. A. (2011). Global warming vs. climate change, taxes vs. prices: Does word choice matter? Climatic Change, 105(1), 1–12.

Visschers, V. H., & Siegrist, M. (2012). Fair play in energy policy decisions: Procedural fairness, outcome fairness and acceptance of the decision to rebuild nuclear power plants. Energy Policy, 46, 292–300.

Wichman, C., Taylor, L., & von Haefen, R. (2016). Conservation policies: Who responds to price and who to prescription? Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 79, 114–134.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that s/he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this research were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clayton, S. The Role of Perceived Justice, Political Ideology, and Individual or Collective Framing in Support for Environmental Policies. Soc Just Res 31, 219–237 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-018-0303-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-018-0303-z