Abstract

We studied the development, profile, and income mobility among individuals in in-work poverty in Sweden over a period of 30 years using data covering the entire population on a yearly basis from 1987 to 2016. By introducing a more solid work requirement that stretches over more time than the frequently used ‘seven-month rule’, we make sure that the in-work poor person in our study is mainly working. Our results show that the profile has changed: in 1987, the typical in-work poor person was a native-born single woman, but in 2016, they were a married man born outside of Sweden. When modelling income mobility over two 5-year periods, our results show that changes in household composition explain both upward and downward mobility and that it has become harder to change income position. Interpreting the results on a structural level, two conclusions can be drawn. As in-work poverty is no longer female-dominated, the Swedish policy for gender equality has been successful. As it is now closely connected with immigration status, the integration of immigrants into the labour market must improve.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In the ongoing debate on minimum wages, integration, and ways into the labour market, changing wage levels are often presented as a solution to unemployment and exclusion. To avoid in-work poverty, the European Parliament has highlighted the importance of a decent income, including a decent wage, and states:

Workers have the right to fair wages that provide for a decent standard of living. Adequate minimum wages shall be ensured, in a way that provides for the satisfaction of the needs of the worker and his / her family in the light of national economic and social conditions, whilst safeguarding access to employment and incentives to seek work. In-work poverty shall be prevented. (European Commission, 2017, Chapter II: Article 6).

How to decrease in-work poverty by means of political measures and new policies is on the political agenda nowadays (Eurofound, 2021; Peña-Casas et al., 2019; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020). In-work poverty is, of course, not a constant status—it may change according to different demographic drivers, such as the number of children in a household, and being a single parent (Andress & Lohmann, 2008; Hick & Lanau, 2018). One of the most highlighted aspects in this context is the situation for migrants, and the results of several studies have shown that non-EU citizens in particular are facing in-work poverty to a higher degree than EU-native-born citizens (Branyiczki, 2015; Crettaz, 2018; Lohmann & Marx, 2018).

In-work poverty is a bi-dimensional construct, as it refers to both the household level and the individual level. When measuring the extent of in-work poverty, there are some generally agreed indicators at the EU level (Bardone & Guio, 2005). The individual household’s disposable income has to be equal to or less than the relative poverty line, which is defined as an equivalent disposable income equal to or below 60% of the median equivalent disposable income. The poverty line for the household is thus established.

How to define who is counted as being in in-work poverty involves defining a ‘working threshold’, and there is an ongoing discussion where different definitions are used (see, e.g., Jansson & Broström, 2020; Lohmann, 2018). The main interest is in how to define the minimum amount of work that should be used to determine a working threshold which—together with the poverty line—should be used to define and measure the size of the population that can be considered as being in in-work poverty. In 2005, Eurostat introduced the definition of an in-work poverty line that is most frequently used at the EU level nowadays (Bardone & Guio, 2005). This definition refers to individuals who have worked mainly during the reference year (i.e. employed or self-employed) and whose household equivalent income is below 60% of the country’s median equivalent income. The definition of being in work was set as 7 out of 12 months of the year. This ‘seven-month rule’ is used extensively, especially in studies conducted since 2005 (Eurostat, 2010; Lohmann, 2018; Marx & Nolan, 2012; Torsney, 2013). The Eurostat definition does not, however, specify this ‘seven-month rule’ of work in terms of work intensity and/or hourly wage and is, in our opinion, constructed in such a way that the requirement to be considered as working is very low. We argue that it will lead to a bias, as it includes, for example, precarious workers who frequently exit and enter the labour market and students who work part-time during semesters and holidays. The mobility in the group will then be overestimated. The number and composition of the in-work poor will be misleading and seen as a temporary problem for mainly young people. By introducing a more solid work requirement that stretches over more time than this ‘seven-month rule’, and the use of the concept of earned income, we ensure that the in-work poor person in our study is mainly working.

Although research about in-work poverty has grown substantially over recent decades, there is a lack of longitudinal analysis, which is important for understanding its duration and persistence. If in-work poverty is just a transitory, temporal phenomenon, or if individuals remain in in-work poverty and if so—why do they stay in in-work poverty? Research findings often conclude that low income is only a temporary stage for the individual or household at the beginning of a person’s working life. Due to these assumptions, studies on the development of and changes in the characteristics of the in-work poor and their possibilities for income mobility are lacking. To our knowledge, there are just a few longitudinal studies of household panels (Cappellari & Jenkins, 2008; Clark & Kanellopoulos, 2013; Hick & Lanau, 2018; Riphahn & Schnitzlein, 2016).

This study focuses on in-work poverty in Sweden over a time span of 30 years, from 1987 to 2016. The Swedish labour market is often portrayed as stable for those who have a regular job since they are well protected through collective agreements. Earlier studies about in-work poverty in Sweden have used sample data (household panels) and have considered shorter periods than ours (e.g. Halleröd & Larsson, 2010; Halleröd et al., 2015). In other studies, women and migrants have been found to have an increased risk of being in in-work poverty (Lohmann & Marx, 2018). We investigated whether there is a similar pattern for Sweden.

The aim of this article is twofold. Firstly, it focuses on how in-work poverty has developed in Sweden over a 30-year period, from 1987 to 2016. By using a more solid work requirement, we investigate the extent of in-work poverty and the demographic profile of the in-work poor and answer the following questions: how has in-work poverty changed according to age, gender, level of education, civil status, and country of birth? What differences between individuals in in-work poverty of the same age, gender, and so on, can be observed between the start (1987) and end (2016) years? By using a data set that includes the total population (yearly) in Sweden for such a long period, we are able to reveal the profile and dynamics of income mobility among individuals who actually are in in-work poverty and how they have changed during the studied period.

Secondly, the article focuses on income mobility, that is, the intragenerational income mobility among individuals in in-work poverty, by investigating mobility according to three different outcomes: who stays in in-work poverty, who obtains an increased income, and who obtains a decreased income. In addition, we investigate the extent to which mobility is connected to and explained by life cycle changes. By examining the mobility processes among individuals in in-work poverty in Sweden over a 30-year period from 1987 to 2016, this study can contribute to an understanding of policies and reforms that are needed to help people move out of in-work poverty. The research designs are further explained and discussed in Sect. 3.4.

The results from this study will also contribute to a deeper understanding of the mechanics of in-work poverty and income mobility, an understanding that is necessary when reforming social policy and the labour market to help people out of in-work poverty. Therefore, we consider our study to be of interest not only in Sweden but also in other countries with increasing numbers of households and individuals in in-work poverty. Knowledge is necessary to reveal the profile and dynamics of in-work poverty, and to understand whether in-work poverty can be considered as a low-income problem or an issue due to institutional and/or labour market conditions when framing reforms and social policies in this field.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 gives a general background to the Swedish context. In Sect. 3, the data, definitions, and methods are presented and discussed. Section 4 presents and discusses the results of changes in the profile of the in-work poor. In Sect. 5, the mobility within the group is presented. Section 6 discusses the findings and draws conclusions.

2 The Swedish Context

Economic development in Sweden during the studied period (1987–2016) has taken different turns, which might have had consequences for the in-work poverty rate. For the majority of the twentieth century, the Swedish labour market has been characterized by collective agreements, extensive union membership, and, overall, being a high-wage country (Lundh, 2010). In line with that, in-work poverty is often assumed to be negligible or non-existent.

At the beginning of the 1990s, Sweden experienced a deep economic downturn, which had several pervasive consequences for the economy. GDP growth was negative in 1991–1993. The labour market was particularly affected by this economic crisis. Sweden left its post-war full employment state and ever since has dealt with a higher unemployment rate. In 1993, a Temporary Agency Work Directive was implemented to meet the fluctuating demand for labour. The state’s monopoly on employment agencies was removed in favour of a mix of both private and public agencies. Fixed-term employment arrangements subsequently increased (Broström, 2015). In recent research into the Swedish labour market, two trends have been revealed—dualisation and polarisation. Dualisation is shown as an increase in temporary employment, mainly characterised as a political process that changes and differentiates central institutions by making distinctions between the rights and benefits of so-called insiders and outsiders of the labour market. This ongoing process involves the creation of both gig jobs and ‘involuntary’ self-employed entrepreneurs and consultants (Engblom & Inganäs, 2018). Polarisation refers to increased employment in both low- and high-paid jobs and decreased employment in middle-paid jobs. As a result of digitalisation and automation, the number of routine jobs has decreased in both manual and cognitive occupations, jobs that tended to place in the middle of the wage distribution (Berglund et al., 2017, 2020).

The Swedish recovery has been strong. Between 1995 and 2004, the GDP growth rate was 2.6% per annum, and Sweden had higher GDP growth rates than all the other EU countries and the US (Regeringskansliet, 2006). During the 2007–2014 period, GDP increased on average by 1.3% per year (Konjunkturinstitutet, 2014). Since the end of the 1990s, the unemployment rate has fluctuated between 6 and 9% (Statistics Sweden, 2019). What previous research has shown is that there has been a decline in absolute poverty but an increase in relative poverty connected to the changes in the labour market (Bengtsson et al., 2014). During the twentieth century, Sweden has been considered to be a country with extensive and increasing income mobility (Björklund & Jäntti, 2009). One study has shown that upwards income mobility for low-paid workers in the 1980s and 1990s in Sweden was extensive (Keese et al., 1998). Recent research about income mobility has indicated that it has been slowing down. More people stayed in their income positions, especially those in the top and bottom deciles, from 2000 to 2016 than in earlier periods. Young adults, of course, have a greater tendency than older people towards upward mobility; the same applies to men compared with women, although this gender gap is slowly closing (Statistics Sweden, 2018).

In Sweden today, women still have lower wages than men on average and many top jobs are still clearly male dominated. However, the wage gap between women and men has decreased from 18% in 2000 to 9.8% in 2020 (Medlingsinstitutet, 2020). The right to full-time employment, skills increase, more employers, quotas for education and opportunities to combine family and working life are all phenomena that have worked in favour of women’s labour force participation and wage development. The gender equality policy has successfully changed the situation for women on many levels (Regeringen proposition, 2018/19:100: p. 20).

Another aspect to take into consideration in understanding the development of in-work poverty is demographic changes. In 1990, the share of foreign-born individuals in the population was 9%, and in 2018, it had increased to 19.1% (Statistics Sweden, 2019). Sweden is one of the largest net receivers of immigrants as a percentage of the population in Europe, due to wars and conflicts both within and outside Europe, but also of labour migrants. They are not a homogenous group, but their overall traits have been a lower education level than native Swedes in general and limited Swedish-language skills, which are often required for jobs. This has affected the unemployment rate among immigrants and the time taken to become established on the Swedish labour market (Forslund et al., 2017). Many factors affect the establishment in the labor market. Country of birth, reasons for migration, age and education on arrival are some of the more important ones related to the individual. But also, the economic situation, the labor market in the place of residence or placement, attitudes of employers, networks and communications play a role, as well as labor law and access to labor market policy programs (SOU 2020:46: p. 364).

3 The Data, Definitions, and Methods

The data used in this study are register data from Statistics Sweden, including the total population registered as living in Sweden for each year from 1987 to 2016.Footnote 1 We have yearly information on all individuals, which includes many variables, of which a few were chosen for this study: different income variables, gender, age, level of education, civil status, number of children, and country of birth. We focused on individuals of active working age from 18 to 65 years, and in total the data consisted of 4,556,674 individuals in 1987 and 5,102,460 individuals in 2016. The data are constructed as a panel. In this study, we used the data both as a cross-section, when measuring changes and profiles of in-work poverty, and as a balanced panel, when measuring the income mobility among the in-work poor. The balanced panel consist of individuals who belonged to the in-work poor group in the first year of observation and measured their disposable income 5 years later. The number of individuals in in-work poverty that were included in the panels was in total 64,726 in 1987 and 70,635 in 2016.

3.1 Two Income Definitions—Household Disposable Income and Individual Earned Income

In-work poverty is a bi-dimensional construct so to be able to define who is counted as in-work poor, we needed to work with two separate income definitions: firstly, household disposable income (HDI), which is based on the merged household income; and secondly earned income pre-tax (EI), which is the individual’s own personal earned income.

When calculating the HDI, the variable ‘equivalent disposable income’ was used. This variable includes (earned income + self-employed income) + nominal capital income + transfers − tax (i.e. post-distributed and post-taxed income). Examples of transfers are payments from sickness insurance, parental insurance, and so on; nominal capital income derives from fiscal sources and include dividends, interest, and rents. The household is the income unit, and the individual is the unit of analysis, as all household members’ disposable incomes are merged. The variable equivalent disposable income is used as it is adjusted for the household expenditure needs (using an equivalence scale).

When calculating the individual EI, we created a new variable called ‘earned income pre-tax’, which includes two existing variables in the data set: earned income + self-employed income. ‘Self-employed income’ includes individuals with both an earned income and an income from self-employment as well as the group of self-employed people who receive income only from their self-employment. The variable ‘earned income pre-tax’ in our data set is comparable to the variable ‘earned income pre-tax’ used by other researchers (e.g. Schnabel, 2016). All the calculations are on a yearly basis and in fixed prices (2017).

3.2 Defining Who is Counted as In-Work Poor

As stated earlier, there are some generally agreed indicators at the EU level (Bardone & Guio, 2005). The individual HDI has to be equal to or less than the relative poverty line and the individual has to be defined as working. In this study, we challenge the most frequently used definition of working, the ‘seven-month rule’, which refers to individuals who have mainly worked during the reference year (i.e. employed or self-employed) but lacks a definition of work in terms of work intensity and/or hourly wage (Eurofound, 2021; Eurostat, 2010). This work requirement is connected with the definition of employed:

In the context of the Labour force survey (LFS), an employed person is a person aged 15 and over (or 16 and over in Iceland and Norway) who during the reference week performed work – even if just for one hour a week – for pay, profit or family gain. Alternatively, the person was not at work, but had a job or business from which he or she was temporarily absent due to illness, holiday, industrial dispute or education and training.Footnote 2

In our data set, we have information on EI for all individuals living in Sweden on a yearly basis and using this, we are able to introduce a more solid work requirement. We operationalize the ‘seven-month rule’ of work as at least 60% of the median earned income pre-tax. The advantage of this, as we find it, is that it now includes individuals whose income is mostly derived from work, although it signals that their labour market attachment is weak. To be defined as in-work poor, in this study, these two conditions had to be fulfilled: the individual HDI had to be equal to or less than the relative poverty line and the individual had to have an individual pre-tax EI of at least 60% of the median earned income pre-tax for each separate year.

The debate about a European minimum wage suggests setting it to at least 50% of average and 60% of median wages in each separate country (Eurofound, 2021). Our definition is very close to this minimum wage proposal and the result will reveal whether it is enough to prevent in-work poverty in a Swedish context and, most probably, in a European context as well.

The group focused on in this study is shown in Table 1 as the ‘in-work poor’.

When using this definition (results not shown here), the number of individuals who are in-work poor in our data set is 64,726 in 1987 and 70,635 in 2016. The proportion of the working-age population considered to be in in-work poverty is the same for the first year of observation, 1987, at 1.4%, as for the last year, 2016, when it is also 1.4.Footnote 3 This result differs from the official statistic of 7% in Sweden in 2018 using the EUROSTAT definition (Statistics Sweden, 2018). Divided according to gender, the majority of individuals in in-work poverty were women in 1987, with 45,599 women and 19,127 men. In 2016, this had changed as the majority of individuals in in-work poverty were men, with 37,463 men and 33,172 women.

3.3 The Gender Paradox

The change in the gender composition of individuals in in-work poverty leads us to a discussion about the gender paradox. As stated earlier, the household is the income unit, and the individual is the unit of analysis, since all household members’ disposable incomes are merged. This is based on the assumption that all incomes in the household are shared equally between all household members, which gives everyone in the household an equal standard of wellbeing—an assumption which has been disputed (Boschini & Gunnarsson, 2018; Lundberg & Pollak, 2008; Ponthieux, 2013). A consequence of this assumption (equal sharing) is that it will lead to the gender paradox, that is:

while women on average are highly over-represented in the less favourable labour market positions and at the bottom of the earnings distribution, they do not face disproportionate risks of in-work poverty (Ponthieux, 2018, p. 70).

This means that if a low-income woman marries a high-income man, she will end up not poor although her personal income has not changed. One way of explaining and measuring this paradox is to investigate labour force participation. Research has shown that a majority of men and women marry their peers; that is, foreign-born marry foreign-born and native-born marry native-born (Choi & Tienda, 2017). If there is a difference between native-born and foreign-born labour force participation, this can result in a higher degree of poverty within the group where labour force participation is low. Sweden has a high female labour force participation rates and the size of the gap between native-born and foreign-born women could be an indicator of how well the integration of female immigrants into the Swedish labour market is working.

Table 2 shows the labour force participation among native-born and foreign-born people aged 25 to 54 years from 2005 to 2020.

As shown in Table 2, the gap between native-born women and foreign-born women has increased from 20 to 25%. The opposite is shown for men, where the gap has decreased from 20% to 13%. We return to the gender paradox when interpreting some of the results.

3.4 Methods

The study was carried out in two steps. The first step describes the development of in-work poverty and the profile of the in-work poor according to some demographic characteristics in the starting year of 1987 as well as how it had changed 30 years later in 2016. Here all calculations were based on cross-sectional data. The development of in-work poverty was calculated based on yearly data. To capture the major changes of the profile the starting year (1987) was compared with the ending year (2016) in the data set.Footnote 4

The second step was to investigate the income mobility in the in-work poverty group. In-work poverty might be a transitory, temporal phenomenon and mobility was therefore measured over periods of 5-years. The reason for choosing a time span of 5 years was to capture the invariability of in-work poverty, as incomes might change from 1 year to the next, and as other research has shown the most in-work poverty episodes are rather small (Vandecasteele & Giesselmann, 2018). By using a time span of 5 years, we captured the households that were in a vulnerable economic situation as years passed by. As we were interested how mobility changed over 30-years we measured and compared mobility in the starting years with the ending years. Two balanced panels were created, each for a period of 5 years.

The first balanced panel includes the first 5 years in the data set, from 1987 to 1991, and has a total of 63,649 individuals (18,484 men and 45,165 women). The second panel includes the last 5 years, starting with 2012 and ending with 2016, and has a total of 80,084 individuals (42,741 men and 37,343 women). Because of the use of register data, the attrition was small. To be included in these panels, individuals had to be counted as ‘in-work poor’ in the starting year (1987 or 2012) and still be in the panel data set in the ending year (1991 or 2016). We were interested in investigating the income mobility within the groups during these periods: who stayed in in-work poverty, who exited to a higher income, and who exited to a lower income. As there are still a limited number of methods—and no established method—for measuring in-work poverty as a dynamic, transitory phenomenon (Jenkins, 2011; Vandecasteele & Giesselmann, 2018), a multinomial logit model was estimated.

Our interest lay in determining how income mobility had changed over the two 5-year periods. To understand how relative income change is affected by changes in life cycle, a multinomial logit model was used for each 5-year period (i.e. relative mobility, which reflects changes in the individuals’ relative positions).

Three possible outcomes were defined according to the individual household’s disposable income during the last year of observation compared with its disposable household income during the base year. ‘Downward mobility’ was defined as less than 98%, ‘relatively immobile’ as between 98 and 128%, and ‘upward mobility’ as 128% or more of the former income. These classifications captured any major changes in income while allowing various explanatory variables to affect increases and decreases differently. Five groups of explanatory variables were included: age, level of education, the same or changed number of children, the same or changed civil status, and country of birth.

The multinomial logit investigates the determinants of downward and upward mobility for men and women in the two different panels at time t. It can be used when all the independent variables are case-specific (Ricci, 2016). It specifies that

where \({x}_{i}\) are the independent variables, and the intercept. This model ensures that 0 < \({p}_{ij}\) < 1 and \({\sum }_{t=1}^{m}{p}_{ij}\) = 1. To ensure model identification, \({\beta }_{j}\) is set to zero for one of the categories (in this case relatively immobile) and the coefficient can be interpreted with respect to the base category. In this presentation, the parameters are transformed into odds ratios, where the odds ratio of being a member of category j rather than alternative 1 is given by

where \({e}^{\beta jr}\) gives the proportionate change in the relative risk of being in j rather than 1 when \({x}_{ir}\) changes by one unit. Observable characteristics such as age, level of education, number of children, civil status, and country of birth enter the vector \({x}_{i}\) and the relationship between each characteristic and the dependent variable is thus studied. Specifically, we estimated the impact of several variables on the probability of moving downward or upward in income, using immobility in income status as the reference category. We performed modelling to obtain results for each type of transition including age, level of education, the same or changed number of children, the same or changed civil status, and country of birth. The results revealed whether and how the impact of these variables changed the possibilities for income mobility in the group of in-work poor and whether there were any differences between the two balanced panels.

Together these two different types of measurement of inequality and income mobility (cross-sectional and panel) reveal the patterns of income inequality and income mobility in the group of in-work poor.

4 Is the Profile of the In-Work Poor Changing?

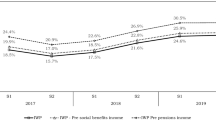

Starting with the profile of the in-work poor, Fig. 1 shows the development of in-work poverty in Sweden over a period of 30 years. As shown, the rate of in-work poverty was rather high for women (more than 2%) compared with men (less than 1%) in the starting year, 1987. The dramatic drop for women between 1990 and 1991 is explained as being a consequence of the tax reform implemented in 1990–1991. The tax base was broadened and capital income was taxed independently of work earnings using a proportional rate. Middle- and high-income earners benefitted the most from this reform, and to improve the distributional effect, extra tax relief in the form of an increased basic allowance was introduced for individuals on low incomes. Some transfer payments, such as child benefit and housing benefit, were increased, and this worked in many ways in favour of women (Regeringen, 1997/98).Footnote 5

Furthermore, Fig. 1 shows that the rate of in-work poverty has been increasing since the 1990s for both men and women. At the beginning of the 1990s, Sweden went through an economic crisis and faced high rates of unemployment, and these high rates explain the low levels of in-work poverty.Footnote 6 Since the 1990s, there has been an upward trend in in-work poverty, and the rate has more than doubled for both genders. A small downturn in the trend is observable in 2014 and is explained by some policy reforms, such as an increase in the amount of transfers in the form of child benefit, child support, and unemployment benefit in 2015.Footnote 7

Demographically, Sweden has changed a great deal since 1987, and the proportion of foreign-born population increased from approximately 9% of the total population in 1990 to approximately 19% in 2018.Footnote 8 In Fig. 2, the rates of in-work poverty are divided according to country of birth, using four country groups derived from the World Bank (2019) classifications.

As shown in Fig. 2, the difference between Swedish-born and foreign-born individuals was negligible in the starting year of 1987. With the economic downturn in the early 1990s, the difference between being born in Sweden or another high-income country or in a middle- or low-income country starts to show—a process that becomes more and more visible as time passes. In the end year, 2016, we find that being in in-work poverty is closely connected with immigrant status, as it was in 1987, and the proportion of individuals in in-work poverty who were Swedish-born in 1987 was 87.8%, compared with 51.3% in 2016.Footnote 9 In-work poverty has become associated with immigrant status and a precarious situation in Sweden as well as in other EU countries (see Crettaz, 2018).

To understand the group of in-work poor, we explored the composition of the group and how it has changed over the 30-year period. Which socio-demographic groups faced a higher risk of in-work poverty at the beginning of the period? And how has this changed 30 years later? As shown in Table 3, there are quite large changes in the age composition according to gender. In 1987, almost one quarter of the women were young (aged 18 to 29 years); in 2016, this figure had changed to just 7.6%, whereas the situation is different for young men, whose share was almost the same during that period.

Being in in-work poverty, as shown in Table 3, is not typical for young adults, as the majority are of active working age (30 years old and above), although there is a shift to older age groups in 2016. This result contradicts other research which states a large risk of in-work poverty among young adults (e.g. Halleröd & Larsson, 2010; Nelson & Fritzell, 2019). The reason for this contradiction is the use of a more solid work requirement in this study. By using it another age composition is visualized. Results show that in-work poverty is more a reality for individuals in prime working age as individuals with very weak labour market attachments, such as students working during summer vacations and seasonal workers, are excluded in the calculations.

The in-work poor’s level of education has shifted distinctly. In 1987, a majority of both men and women in in-work poverty had low levels of education (primary and secondary education). In 2016, a majority of women had a tertiary education (63.7%) and so had half of all the men. The changing labour market has led to a demand for higher education and, as shown in Table 3, there were more foreign-born individuals among the in-work poor in 2016. One explanation as to why the highly educated are now in this group is the hardships and discrimination many well-educated immigrants face when entering the Swedish labour market (Åslund et al., 2017).

When looking at civil status, the difference between genders is obvious. In 1987, the majority of women were single or divorced compared with a majority of married men. Thirty years later, the share of married women had increased—from 14.5% in 1987 to 39.8% in 2016. This might be a consequence of the ‘gender paradox’. In 1987, the high share of married men in the in-work poor group can be explained by the use of the assumption of ‘equalized disposable household income’, which pools income in the family. Under this assumption, a man with low- or middle-income married to a low-income woman will have a higher risk of being in in-work poverty. For women, the risk of being in in-work poverty when married was only 14.5% in 1987. Why it has increased to 39.8% in 2016 can be explained by the poor income development for male low-income earners in recent decades. Results from earlier research have shown and led to discussion of an ongoing povertization of men in Sweden as their income growth has slowed down substantially compared with middle- and high-income male income earners (Broström & Rauhut, 2018). A married low-income woman in 2016 was probably married to a low-income earner man and their merged household income was too low to help them over the poverty line. Being a single-headed household (single or divorced) signals a higher risk of being in in-work poverty for a woman, as her household’s disposable income consists only of her income.

As shown earlier, in Fig. 2, the majority of individuals in in-work poverty were Swedish-born in 1987. Table 3 shows the same development, but according to gender. In 2016, the majority of men in in-work poverty had a non-Swedish background. Swedish-born women were still in the majority, but by then their share had decreased from 89.5% to 61.4%. This can be explained by their increased rate of labour force participation in combination with the lower rate of labour force participation among foreign-born women. The share of individuals of both genders from middle- and low-income countries has increased substantially, which reveals the increasing risk of experiencing in-work poverty among immigrants.

The profile of the in-work poor has changed over a time span of 30 years. In 1987, the typical in-work poor person was a native-born single woman aged 30 to 49; in 2016 they were a foreign-born married man in the same age range. In-work poverty has become a problem that concerns not just income but also integration into the Swedish labour market. And, as few marriages are intercultural marriages and foreign-born women have lower rates of labour force participation than native-born women, the gender paradox is clearly visible.

Comparing results from this study with other studies we find similarities as well as differences. The nowadays almost similar risk of being in in-work poverty for men and women is consistent with results from other European countries, except in Germany (Nelson & Fritzell, 2019; Ponthieux, 2018). Migrants, especially from middle- and low-income countries, increased risk of being in-work poor are observed in other European countries (Crettaz, 2018). But when comparing the risk, it is lower in Sweden than in EU 28, an observation which can be interpreted as that integration of migrants into the labour force are a bit more successful in Sweden (Nelson & Fritzell, 2019).

Now we turn to the next step of the analysis: whether in-work poverty is temporary or permanent.

5 Modelling Income Mobility Among the In-Work Poor

One of the primary reasons for studying mobility is that it gauges inequality. If our results show that in-work poverty is mainly a transitory phenomenon (or otherwise), it will determine whether we treat it as a social problem. We now use the balanced panel and measure changes in disposable income, dividing the 30 years of data into two 5-year periods. We measure the proportion of households that stay in in-work poverty or change position, either upward or downward. Our results, not shown here, indicate a declining mobility. In the first period from 1987 to 1991, 87.5% had an upward income mobility. Furthermore, 7.6% maintained the same income and 4.9% experienced a decrease in income. In the second period, from 2012 to 2016, 68.2% had upward income mobility, 18.9% maintained the same income, and 12.9% experienced downward income mobility.Footnote 10 To understand and determine whether this decreasing mobility can be explained by age, level of education, number of children, civil status, and country of birth, results from the multinomial logit are shown in Tables 4 and 5, expressed as odds ratios.Footnote 11

Starting with Table 4, which covers the starting years 1987 to 1991, the results show that age matters, but not for young adults (18–29 years old). Instead, it is among the ‘mature’ adults (age 40–49 and 50–59) that we find an upward mobility for men (OR 1.48 and OR 1.54) as well as for women (OR 1.99 and OR 3.06). The upward mobility for women is explained by their increased labour force participation, as their childbearing years are behind them. Exiting the labour market and retiring (age group 60–65 years) also leads to an improvement in income for both genders, probably as a consequence of obtaining a stable income as a retiree. A tertiary level of education can lead to both upward and downward mobility for both genders. Having children in the household is costly, and when the children leave the household, there is an improvement in income, shown as OR 1.99 for men and OR 2.18 for women. For the variables measuring civil status and changes in civil status, the results show that for an unmarried woman who gets married, there is a real improvement in income (OR 4.49). This is part of the gender paradox. A woman with a low income changes her income status as her income is merged with the income of her partner, and the equalized disposable household income will then, in all probability, be higher. As shown earlier (Fig. 2), country of birth matters, as downward incomes are observed for all three groups.

For the second period shown in Table 5, covering the ending years 2012 to 2016, we find that age now matters for young adults (18–29 years old). There is a real improvement in income as they grow older (OR 1.46 for men and OR 1.80 for women), probably as a consequence of getting a higher education, which has increasingly been a demand in the changing labour market. For women, there are increases in income in all age groups. Having tertiary education matters for both genders (OR 1.29 for men and 1.23 for women). Having children in the household is still costly, and there is no improvement in income if women have fewer children when compared with the earlier period (Table 4). In this period, the gender paradox is indeed demonstrated, as married women have high odds (OR 1.30), like women who get married (OR 2.53), of upward income mobility. For men, the effect is the opposite, which also corresponds to the gender paradox. Looking at the variable ‘country of birth’, we find that the odds of downward income mobility for both genders hovers around OR 1.31 to 1.05 (Table 5). Being an immigrant in Sweden increases the risk of having a declining income, with the exception of male immigrants from high-income economies (OR 1.17). But compared with the first period (1987–1991) the odd ratios of having a declining income are lower, indicating a better integration of immigrants into the Swedish labour market for both genders.

Results indicate that there have been some major changes in mobility in the in-work poor group over the 30-year period in Sweden. Mobility has decreased and in-work poverty has become more permanent, especially for immigrants, families with children, and the divorced. In addition, the gender paradox is shown here as a married man or a man who gets married remaining relatively immobile, unlike a woman. The influence of demographic drivers of in-work poverty is clearly shown in the results. These findings correspond to earlier research which points out demographic drivers (e.g. household composition, number of children, civil status and changes in civil status, and country of birth) as important to factors explaining mobility (Crettaz, 2018; Ponthieux, 2018; Thiede et al., 2018; Vandecasteele & Giesselmann, 2018).

6 Conclusions and Discussion

The aim of this study was to contribute to the research on in-work poverty and income mobility among in-work poor persons. By introducing a more solid work requirement that stretches over more time than the frequently used ‘seven-month rule’, we make sure that the in-work poor person in our study is mainly working. Our working threshold is also set close to the minimum wage suggested by the EU, that is, at least 50% of average and 60% of median wages in each separate country (Eurofound, 2021). The results will thereby indicate whether a minimum wage at that level will be enough to provide for a decent standard of living and prevent in-work poverty in a Swedish context and, most probably, in a European context as well.

The focus of the study was how in-work poverty has developed in Sweden over a 30-year period, how the profile has changed, the development of income mobility for individuals in in-work poverty, and whether in-work poverty is a transitory status.

In 1987, when this study begins, women experienced in-work poverty to a greater extent than men. There was, however, a sharp drop in in-work poverty among women in the early 1990s, explained by increased transfer payments such as child benefit. Since 1995, there was a steady increase of in-work poverty for both genders until 2015, when a small decrease is observed. This 2015 decline is also explained by political reforms, as the amount of some transfers was increased (child benefit, unemployment insurance, etc.). Other studies confirm that in-work poverty nowadays is more gender neutral, the risks of being in in-work poverty is more or less the same for men and women in EU (Nelson & Fritzell, 2019; Ponthieux, 2018). This might be a consequence of higher female labour force participation among younger generations.

Looking at the profile of the in-work poor, it becomes clear that it has changed. In 1987, the typical in-work poor person was a native-born single woman aged 30 to 49 years. In 2016, they were a married man, foreign-born, aged 30 to 49 years. These results point to the vulnerable situation of being an immigrant, particularly from a low-income country, as this increases the risks of experiencing in-work poverty. Among Swedish-born men, the in-work poverty rate has almost halved—from 83 to 43% between 1987 and 2016—and the reduction among Swedish-born women was from 89 to 61%.

What are the opportunities for an individual in in-work poverty to change their income position? If in-work poverty is just a temporary status—one that lasts only a year or two—it will not affect income inequality to a high degree. If it is a permanent status, where an individual has a low-income over a longer period, it will affect their life chances more seriously. We found decreasing mobility among individuals in in-work poverty. At the beginning of the study period, from 1987 to 1991, the percentage of individuals who moved out of in-work poverty to a higher income was 87%, while 8% remained in in-work poverty and 5% experienced a decreasing income as they became poor. At the end of the study period, from 2012 to 2016, mobility had decreased. By then, 68% had moved out of in-work poverty to a higher income, 19% remained in in-work poverty, and 13% had experienced a drop in income. This decreased mobility is consistent with results from research of income inequality and income mobility which show a decreasing mobility among low-income earners in general (Björklund & Jäntti, 2011; Jenkins, 2011; Salverda & Haas, 2014).

The results of modelling income mobility show that household composition played a major role in explaining mobility. At the beginning of the study period, we find a strong upward mobility for women as they grow older. This is a consequence of increased labour market participation when their childbearing years are behind them and the children leave the household. Changes in civil status also affect income mobility in a positive way for women, as an unmarried woman who gets married has a chance to improve her income (OR 4.49). Country of birth matters for downward mobility for both periods. Being an immigrant in Sweden increases the risk of having a declining income.

When interpreting these results on a structural level, two conclusions can be drawn. Concerning Swedish policy for gender equality, the development has been successful, as in-work poverty is no longer female-dominated. Concerning the integration of immigrants into the labour force, it has been unsuccessful as in-work poverty is now closely connected with immigration status a result drawn from investigating the profile of the in-work poor. On the other hand when interpreting results from measuring mobility a different picture is shown. Here we found small differences in odds ratios according to countries of birth for both men and women during the last period. This can be interpreted in two ways. First, that the integration of immigrants into the Swedish labour market worked better in the 2010s than in the 1980–1990s. Secondly, this is a result of the decreasing mobility for low-income earners in general during the 2010s and the situation for immigrants has not improved, it was the situation for the native born that got worse (Björklund & Jäntti, 2011). These two interpretations do not necessary contradict each other, as the profile is based on 1 year, and mobility based on 5 years.

In a European context, there is discussion about a number of direct and indirect policies influencing in-work poverty (Peña-Casas et al., 2019, pp. 52–72). Among the direct policies are taxes and social security contributions, family benefits, active labour market policy, and tackling labour market segmentation. Among the indirect policies, we have childcare policies and lifelong learning. Looking at the results from this perspective, we argue that the decrease in in-work poverty at the beginning of the period was a result of changes in taxes, increased transfers such as child benefit and housing benefit, and childcare policies, changes that worked mostly in favour of women. However, taking the results together, the main results show decreased income mobility for individuals in in-work poverty in Sweden over the last 30 years. It has become harder to change income positions, and in-work poverty cannot be seen as just a transitory status. To change the situation for people in in-work poverty, there is a need for direct policies, active labour market reforms that work in favour of a more inclusive labour market, tackling discrimination and labour market segmentation, and higher lowest wages. As our study shows, raising minimum wages to the level suggested by the EU will not be enough to prevent in-work poverty.

Availability of data and material

The dataset used for this study is based on linked data retrieved from Statistics Sweden. Sharing of the data is restricted by Swedish data protection laws, according to which administrative data are made available for specific research projects. Thus, the data used for this study cannot be shared with other researchers.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Notes

The data derive from different registered data, for example, tax files and the Register of the Total Population (RTB).

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Glossary:Employed_person_-_LFS, accessed 15 August 2021.

Estimates available upon request.

Estimates covering more years are available on request.

The child benefit is generally paid to the mother. Since 2014, parents have been able to divide it equally if they apply for this.

As many individuals are unemployed, they will not have an earned income pre-tax above the fixed amount on which our calculations are based, as a major part of their disposable income probably derives from transfers, such as unemployment benefit and social security payments.

The Swedish government then consisted of two parties: the Social Democrats and the Green Party.

Statistics Sweden (2019) Befolkningsstatistik. https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/statistik-efter-amne/befolkning/befolkningens-sammansattning/befolkningsstatistik/. Accessed 12 November 2019.

Estimates are available on request.

Estimates are available on request.

OR = 1: exposure does not affect odds of outcome; OR > 1: exposure is associated with higher odds of outcome; and OR < 1: exposure is associated with lower odds of outcome.

References

Andress, H.-J., & Lohmann, H. (2008). The working poor in Europe: Employment, poverty and globalisation. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Åslund, O., Forslund, A., & Liljeberg, L. (2017). Labour market entry of non-labour migrants-Swedish evidence. Working Paper, No. 2017:15. Institute for Evaluation of Labour Market and Education Policy (IFAU).

Bardone, L., & Guio. A-C. (2005). In-work poverty. New commonly agreed indicators at the EU level. Statistics in Focus. Population and Social Conditions 2005-5. Eurostat.

Bengtsson, N., Edin, P.-A., & Holmlund, B. (2014). Löner, sysselsättning och inkomster–ökar klyftorna i Sverige. Rapport till Finanspolitiska Rådet, 1(1), 1–56.

Berglund, T., Håkansson, K., & Isidorsson, T. (2020). Occupational change on the dualized Swedish labour market. In Economic and Industrial democracy (pp. 1–15). (Published online).

Berglund, T., Håkansson, K., Isidorsson, T., & Alfonsson, J. (2017). Temporary employment and the future labor market status. Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies, 7(2), 27–48.

Björklund, A., & Jäntti, M. (2009). Intergenerational income mobility and the role of family background. In B. Nolan, W. Salverda, & T. M. Smeeding (Eds.), Oxford handbook of economic inequality (pp. 491–521). Oxford University Press.

Björklund, A., & Jäntti, M. (2011). Inkomstfördelningen i Sverige. SNS Välfärdsrapport. SNS Förlag.

Boschini, A., & Gunnarsson, K., et al. (2018). Gendered trends in income inequality. In R. Aaberge (Ed.), Increasing income inequality in the Nordics. Nordic Economic Policy Review (Vol. 519, pp. 100–135). TemaNord.

Branyiczki, R. (2015). In-work poverty among immigrants in the EU. Szociologiai Szemle, 25(4), 86–106.

Broström, L. (2015). En industriell reservarmé i välfärdsstaten – Arbetslösa socialhjälpstagare i Sverige 1913-2012. Gothenburg Studies in Economic History 15.

Broström, L., & Rauhut, D. (2018). Poor men: On the masculinization of poverty in Sweden, 1957–1981. Scandinavian Journal of History, 43(3), 410–431.

Cappellari, L., & Jenkins, S. P. (2008). Estimating low pay transition probabilities accounting for endogenous selection mechanisms. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series C (applied Statistics), 57(2), 127–252.

Choi, K. H., & Tienda, M. (2017). Marriage-market constraints and mate-selection behavior: Racial, ethnic, and gender differences in intermarriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 79, 301–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12346

Clark, K., & Kanellopoulos, N. (2013). Low pay persistence in Europe. Labour Economics, 23(C), 122–134.

Crettaz, E. (2018). In-work poverty among migrants. In H. Lohmann & I. Marx (Eds.), Handbook of in-work poverty (pp. 89–105). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Engblom, S., & Inganäs, J. (2018). Atypiska företagare – om relationen mellan företagare och deras uppdragsgivare. TCO, 2018, 1.

Eurofound. (2021). Minimum wages in 2021: Annual review. Minimum wages in the EU series. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission (2017). Chapter II: Article 6. https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/economy-works-people/jobs-growth-and-investment/european-pillar-social-rights/european-pillar-social-rights-20-principles_en. Accessed August 31, 2021.

Eurostat. (2010). In-work poverty in the EU. Eurostat Methodologies and Working Papers.

Forslund, A., Liljeberg, L., & Åslund, O. (2017). Flykting-och anhöriginvandrades etablering på den svenska arbetsmarknaden. IFAU Rapport, 14.

Halleröd, B., & Larsson, D. (2010). In-work poverty and labour market segmentation: Sweden. In DG employment, social affairs and equal opportunities. European Commission.

Halleröd, B., Ekbrand, H., & Bengtsson, M. (2015). In-work poverty and labour market trajectories: Poverty risks among the working population in 22 European countries. Journal of European Social Policy, 25(5), 473–488. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928715608794

Hick, R. O. D., & Lanau, A. (2018). Moving in and out of in-work poverty in the UK: An analysis of transitions, trajectories and trigger events. Journal of Social Policy, 47(4), 661–682. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279418000028

Jansson, B., & Broström, L. (2020). Who is counted as in-work poor? Testing five different definitions when measuring in-work poverty in Sweden 1987–2017. International Journal of Social Economics, 48(3), 477–491. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-06-2020-0417.

Jenkins, S. P. (2011). Chancing fortunes. Income mobility and poverty dynamics in Britain. Oxford University Press.

Keese, M., Puymoyen, A., & Swaim, P., et al. (1998). The incidence and dynamics of low-paid employment in OECD countries. In R. Asplund (Ed.), Low pay and earnings mobility in Europe (pp. 223–265). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Konjunkturinstitutet. (2014). Lönebildningsrapporten 2014. Konjunkturinstitutet.

Lohmann, H. (2018). The concept and measurement of in-work poverty. In H. Lohmann & I. Marx (Eds.), Handbook of in-work poverty (pp. 7–25). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Lohmann, H., & Marx, I. (Eds.). (2018). Handbook of in-work poverty. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Lundberg, S., & Pollak, R. A. (2008). Family decision making. In N. S. Durlauf & L. E. Blume (Eds.), The new Palgrave dictionary of economics (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

Lundh, C. (2010). Spelets regler: institutioner och lönebildning på den svenska arbetsmarknaden 1850–2010 (2nd ed.). SNS förlag.

Marx, I. & Nolan, B. (2012). In-work poverty. Discussion Paper 51, GINI Project. European Commission.

Medlingsinstitutet. (2020). Löneskillnaden mellan kvinnor och män 2020. Vad säger den officiella lönestatistiken? E-print. Stockholm.

Nelson, K., & Fritzell, J. (2019). ESPN thematic report on in-work poverty – Sweden, European Social Policy Network (ESPN). European Commission.

Peña-Casas, R., Ghailani, D., Spasova, S., & Vanhercke, B. (2019). In-work poverty in Europe: A study of national policies. Brussels: European Social Policy Network (ESPN), European Commission.

Ponthieux, S. (2013). Income pooling and equal sharing within the household. What can we learn from the 2010 Eu-Silc module. Collection: Methodologies and Working Papers. Theme: Populations and Social Conditions, European Commission.

Ponthieux, S. (2018). Gender and in-work poverty. In H. Lohmann & I. Marx (Eds.), Handbook of in-work poverty (pp. 70–88). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Regeringen. (1997/98). PROP. 1997/98:1. Bilaga 6. 1990–91 års skattereform – en värdering. Accessed March 15, 2018.

Regeringens proposition 2018/19:100. (2019). 2019 års ekonomiska vårproposition. Förslag till riktlinjer. Accessed April 22, 2020.

Regeringskansliet. (2006). Tillväxten i Sverige fram till idag. www.government.se/sb/d/3923/a/55727?setEnableCookies=true. Accessed August 22, 2016.

Ricci, C. A. (2016). The mobility of Italy’s middle income group. PSL Quarterly Review, 69(277), 173–197.

Riphahn, R. T., & Schnitzlein, D. D. (2016). Wage mobility in East and West Germany. Labour Economics, 39(C), 11–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2016.01.003

Salverda, W., & Haas, C., et al. (2014). Earnings, employment, and income inequality. In W. Salverda (Ed.), Changing inequalities in rich countries. Analytical and comparative perspectives (pp. 49–81). OUP Oxford.

Schnabel, C. (2016). Low-wage employment. Are low-paid jobs stepping stones to higher paid jobs, do they become persistent, or do they lead to a recurring unemployment? IZA World of Labor 16/01/01 (p. 276).

SOU 2020:46. (2020). En gemensam angelägenhet. Betänkande av Jämlikhetskommissionen. Elanders Sverige AB.

Statistics Sweden. (2018). Andelen i arbete under fattigdomsgräns oförändrad. Statistiknyhet från SCB 2018-02-16 https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/statistik-efter-amne/levnadsforhallanden/levnadsforhallanden/undersokningarna-av-levnadsforhallanden-ulf-silc/pong/statistiknyhet/undersokningarna-av-levnadsforhallanden-ulfsilc3/. Accessed August 24, 2021.

Statistics Sweden. (2019). Befolkningsstatistik. https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/statistik-efter-amne/befolkning/befolkningens-sammansattning/befolkningsstatistik/. Accessed November 12, 2019.

Thiede, B. C., Scott, R. S., & Lichter, D. T. (2018). Demographic drivers of in-work poverty. In H. Lohmann & I. Marx (Eds.), Handbook of in-work poverty (pp. 109–123). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Torsney, C. (2013). In-work poverty. In B. Cantillon & F. Vandenbroucke (Eds.), Reconciling work and poverty reduction: how successful are European welfare states? Oxford Scholarship Online.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020). A profile of the working poor 2018. BLS Reports, July 2020, Report 1087.

Vandecasteele, L., & Giesselmann, M. (2018). The dynamics of in-work poverty. In H. Lohmann & I. Marx (Eds.), Handbook of in-work poverty (pp. 193–210). Edward Elgar Publishing.

World Bank Country Lending Group, County Classification. The World Bank: Data 2019. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed November 12, 2019.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Björn Gustafsson and the participants of the seminar held on 12 April 2021 under the research platform ‘A Changing Welfare’ at the Department of Social Work, University of Gothenburg, for discussions and comments on previous versions.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Gothenburg. This study was supported by FORTE (Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life, and Welfare), Grant No. 2017-00338.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The author(s) declares there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Broström, L., Jansson, B. Who are the In-Work Poor? A Study of the Profile and Income Mobility Among the In-Work Poor in Sweden from 1987 to 2016. Soc Indic Res 165, 495–517 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-03025-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-03025-1