Abstract

Using correspondence testing, we investigate how job characteristics affect gender discrimination in hiring. In particular, we analyse whether discrimination against women is moderated by the occupation’s sex composition, required level of decision-making and expected educational level. To do so, we carried out a correspondence study in 2016, in which we sent two pairs of matched male–female applications to 1371 job postings for a heterogeneous selection of occupations in two large cities in Spain. Differences in response rates and response order by gender were then used as a tool to assess discrimination. The results show that job characteristics matter for gender discrimination and that their effects are complementary. Women were particularly discriminated against in connection with jobs that involved decision-making, in male-dominated and mixed occupations, and in jobs requiring both high and low education levels. This discrimination is likely to stem from the activation of both stereotypes and prejudices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

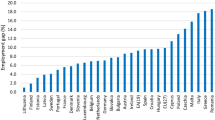

Jobs at the extreme of the sex-ratio composition (having more than 80% men or women) were eliminated from the analysis, because it could be difficult to observe variations by sex in hiring.

Sex ratios and average educational levels for each occupation were estimated using Spain’s Labour Force Survey (2nd quarter 2015).

For anonymity reasons, we do not provide a reference for these figures. It is available upon request.

For 13 of the job postings, the employer closed the selection process before we could send all 4 applications.

In our design, we also contemplated the possibility that the differential treatment shown by the same employer towards women with one trait of interest (e.g., low skills) could vary according to the other trait of interest (e.g., if they had children) by sending six applications to a small subset of job postings (79 job postings, or about 8.5% of all postings applied for). In the analyses we control for the number of applications sent to each job posting.

Alonso-Villar & Coral Del Río (2010) show that women are more segregated at an older age, while men are more evenly distributed across occupations in the Spanish labour market. Gender segregation by age and occupations do not affect our analyses, as we experimentally manipulate the number of fictitious job applicants across occupations and sex groups, and the age of the candidates.

See note 3 above.

See note 3 above.

When we use the words “first” and “fourth” we do not mean to say that employers selected our candidates in that order relative to all candidates who applied to the position, as we do not know which other candidates may have been contacted by the employers, apart from the other fictitious applicants in the set. The order is established exclusively in terms of the time at which our fictitious candidates were contacted.

References

Acker, J. (1990). Hierarchies, jobs, bodies : A theory of gendered organizations. Gender and Society, 4(2), 139–158.

Ahmed, A. M., Andersson, L., & Hammarstedt, M. (2010). Can discrimination in the housing market be reduced by increasing the information about the applicants? Land Economics, 86(1), 79–90.

Albert, R., Escot, L., & Fernández-Cornejo, J. A. (2011). A field experiment to study sex and age discrimination in the madrid labour market. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(2), 351–375.

Aldaz Odriozola, L. & Eguía Peña, B.. (2016). Segregación Laboral Por Género En España y En El País Vasco. Un Análisis de Cohortes. Estudios de Economía Aplicada, 34(1), 133–54.

Alonso-Villar, O., & Del Río, C. (2010). Segregation of female and male workers in Spain: Occupations and industries. Hacienda Pública Española, 194(3), 91–121.

Arrow, K. J. (1973). The theory of discrimination. In O. Ashenfelter & A. Rees (Eds.), Discrimination in labor markets. Princeton University Press.

Azmat, G., & Petrongolo, B. (2014). Gender and the labor market: What have we learned from field and lab experiments? Labor Economics, 30, 32–40.

Baumle, A. K., & Fossett, M. (2005). Statistical discrimination in employment: Its practice, conceptualization, and implications for public policy. American Behavioral Scientist, 48(9), 1250–1274.

Becker, G. (1975). The Economics of Discrimination. Univ. Chicago Press.

Becker, G. (1985). Human capital, effort, and the sexual division of labor. Journal of Labor Economics, 3(1), 33–58.

Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). Are emily and greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. American Economic Review, 94(4), 991–1013.

Bertrand, M., & Duflo, E. (2017). Field experiments on discrimination. Handbook of Economic Field Experiments, 1, 309–393.

Baert, S. (2014). Career Lesbians. Getting hired for not having kids? Industrial Relations Journal, 45(6), 543–561.

Bisping, T. O., & Fain, J. R. (2007). Job queues, discrimination and affirmative action. Economic Enquiry, 38(1), 123–135.

Britton, D. M. (2000). The epistemology of the gendered organization. Gender and Society, 14, 418–432.

Burgess, D., & Borgida, E. (1999). Who women are, who women should be: Descriptive and prescriptive stereotyping in gender discrimination”. Psychology, Public Policy and Law, 5, 665–692.

Bygren, M., Erlandsson, A., & Gähler, M. (2017). Do employers prefer fathers? Evidence from a field experiment testing the gender by parenthood interaction effect on callbacks to job applications. European Sociological Review, 33(3), 337–348.

Correll, S. J., Benard, S., & Paik, I. (2007). Getting a job: Is there a motherhood penalty? American Journal of Sociology, 112(5), 1297–1339.

Drydakis, N. (2014). Sexual orientation discrimination in the Cypriot labour market. Distastes or uncertainty? International Journal of Manpower, 35(5), 720–744.

Eagly, A. H., & Karau, J. A. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573–598.

Ewens, M., Tomlin, B., & Wang, L. (2014). Statistical discrimination or prejudice? A large sample field experiment. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 96(1), 119–134.

Fernández-Muñoz, A., & Blasco-Camacho, M. (2012). Estrategias de búsqueda de empleo. Centro de Estudios Financieros.

Gaddis, S. M. (2015). Discrimination in the credential society: An audit study of race and college selectivity in the labor market. Social Forces, 93(4), 1451–1459.

García-Mainar, I., Montuenga, V. M., & García-Martín, G. (2018). Occupational prestige and gender-occupational segregation. Work, Employment and Society, 32(2), 348–367.

Gorman, E. H. (2003). Gender stereotypes, same-gender preferences, and organizational variation in the hiring of women: Evidence from law firms. American Sociological Review, 70, 702–728.

González, M. J., Rodríguez, J., & Cortina, C. (2019). The role of gender stereotypes in hiring: A field experiment. European Sociological Review, 35(2), 187–204.

Heilman, M. E. (2001). Description and prescription: How gen- der stereotypes prevent women’s ascent up the organizational ladder. Journal of Social Issues, 57(4), 657–674.

Ibañez-Pascual, M. (2008). La Segregación Ocupacional Por Sexo a Examen. Características Personales, de Los Puestos de Trabajo y de Las Empresas Asociadas a Las Ocupaciones Masculinas y Femeninas. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Reis), 123, 87–122.

León, M., & Pavolini, E. (2014). Social investment’ or back to ‘Familism’: The impact of the economic crisis on family and care policies in Italy and Spain. South European Society and Politics, 19(3), 353–369.

McCall, J. (1972). The simple mathematics of information, job search, and prejudice. In A. Pascal (Ed.), Racial discrimination in economic life (pp. 205–224). Lexington.

March, J. G., & Simon, H. A. (1993). Organizations. Blackwell.

Neumark, D., Bank, R. J., & Van Nort, K. D. (1996). Sex discrimination in restaurant hiring: An audit study. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 111(3), 915–941.

Pager, D. (2007). The use of field experiments for studies of employment discrimination: Contributions, critiques and directions for the future. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences, 609(1), 104–133.

Pedulla, D. S. (2014). The positive consequences of negative stereotypes. Social Psychology Quarterly, 77(1), 75–94.

Petit, P. (2007). The effects of age and family constraints on gender hiring discrimination: A field experiment in the French financial sector. Labour Economics, 14(3), 371–391.

Phelps, E. S. (1972). The statistical theory of racism and sexism. American Economic Review, 62(4), 659–661.

Riach, P. A., & Rich, J. (2006). An experimental investigation of sexual discrimination in hiring in the english labor market. Advances in Economic Analysis and Policy, 6(2), 1–20.

Rodríguez Menés, J., & Rovira, M. (2019). Assessing discrimination in correspondence studies. Sociological Methods and Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124119826152

Rudman, L. A., & Glick, P. (1999). Feminized management and back- lash toward agentic women: The hidden costs to women of a kin- der, gentler image of middle managers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1004–1010.

Sahni, H., & Paul, S. L. (2010). Women in top management and job self selection. Social Science Research Network Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2870673

Skyt Nelsen, H., Simonsen, M., & Verner, M. (2004). Does the gap in family-friendly policies drive the family gap ? Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 106(4), 721–744.

Torns, T., & Recio, C. (2012). Las desigualdades de género en el mercado de trabajo: entre la continuidad y la transformación. Revista de Economía Crítica, 14, 178–202.

Weichselbaumer, D. (2004). Is it sex or personality? The impact of sex-stereotypes on discrimination in applicant selection”. Eastern Economic Journal, 30(2), 159–186.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Julia Rubio, Juan Ramon Jiménez and Guillem Subirachs for their contribution to the field work. The authors also thank the Barcelona MAR Health Park Consortium for reviewing the ethical aspects of this research, and the two anonymous referees for their constructive comments on an earlier version of this article.

Funding

Funding was provide by “la Caixa” Foundation (Grant no. Recercaixa2014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors have contributed equally to this article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cortina, C., Rodríguez, J. & González, M.J. Mind the Job: The Role of Occupational Characteristics in Explaining Gender Discrimination. Soc Indic Res 156, 91–110 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02646-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02646-2