Abstract

This article investigates the development of two forms of public spending on families, as well as their role for child poverty in 22 European countries during the period 2006–2015. It uses aggregated data on child poverty from Eurostat and data relating to public spending on families from the OECD SOCX database. It analyses the association between child poverty and public family spending on cash benefits and in-kind benefits, respectively. The findings show a stable growth in the GDP-related and real levels of spending on both cash benefits and benefits in kind, although spending on cash benefits have been more exposed to cost containment than spending on inkind benefits. Furthermore, spending on benefits in kind was found to be more efficient for curbing child poverty than spending on cash benefits, even after controlling for unemployment, family structure, the general standard of living, as well as welfare institutional configurations. However, the efficiency of public family spending declined over the studied period. Moreover, the relative significance of public family spending for child poverty, in comparison to structural factors (such as unemployment), varied according to which spending measure that was used.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Social spending as a percent of GDP has been shown to protect families and children from poverty, even when controlling for household-level factors and other macro-level characteristics as the unemployment rate, affluence and the total level of welfare state generosity (Bárcena-Martín et al. 2017; Chzhen 2017; Muffels and Fourage 2004). The international financial crisis in 2008–2009, which led to a period of sluggish growth and higher unemployment in Europe, became the ultimate test of welfare states’ capacity to cushion families from economic hardship (Richardson 2010). In the period 2006–2009, the average annual growth rate for OECD countries slumped from 3.14 to − 3.45% (Eurostat 2017e). The recession became more profound and lasting in some countries, such as Greece, whereas countries like Germany and Sweden started to recover in 2010–2011 (ibid.). It also increased the share of children living in poor households in most European countries, with the most marked increases in Cyprus, Iceland and Greece (Chzhen et al. 2017).

The policy reactions to the crisis differed between countries. Most European countries increased their social spending when the crisis struck, but while some countries, such as Belgium and France, continued on this line, others such as the UK started to cut spending around 2013 (Chzhen et al. 2017; Ahrendt et al. 2015; Gauthier 2010). To what extent this policy variation explains the development in child poverty over time is not clear. Previous research in this field has mainly focussed on the influence of total social spending on poverty, but we also need to consider the role of different family policy spending, since this reveals not only differences in policy impact, but also whether governments have chosen different spending strategies for combating child poverty in times of recession (cf. Ahrendt et al. 2015; Gauthier 2010). Whereas a ‘service-based’ approach emphasising spending on benefits in kind would be more in accordance with the dual-earner idea within the increasingly influential Social Investment Strategy (Bonoli 2005; Esping-Andersen et al. 2002), a ‘transfer-based’ approach would be more in line with a traditional family policy approach that aims at combating poverty primarily through cash benefits and tax reliefs (Thévenon 2011). However, as the recession following the financial crisis exposed most European countries to mounting fiscal challenges, they also became more prone to engage in fiscal consolidation since 2010–2011 (Taylor-Gooby et al. 2017; Farnsworth and Irving 2015). This ‘era of austerity’ influenced countries in different ways, but it may be assumed that spending on cash transfers to families have become more subjected to austerity measures than spending on services, since the latter is more in line with the EU Social Investment Strategy and the UN Sustainable Development Goals (Chzhen 2017).

The aim of this article is to analyse the development of spending on cash transfers and services, as well as its association with child poverty in 22 European countries over the period from 2006 to 2015. This period covers the years prior to the international financial crisis, but also the post-crisis period during which many governments launched cuts in social expenditures on families (Ahrendt et al. 2015; Richardson 2010; Gauthier 2010). The following research questions are analysed: (a) how has public spending on cash transfers and services changed over this period and to what extent do the observed patters support a shift towards a service-based approach for combating child poverty? (b) How efficient have the two types of family spending been in terms of child poverty reduction when controlling for employment patterns, the overall affluence and welfare state configurations? (c) How has this poverty-curbing efficiency developed over time, and to what extent can we detect divergent paths for these two forms of spending?

The article contributes to the literature on the role of social expenditures on families for child poverty in at least two ways. Whereas earlier studies have focused primarily on the role of total social spending (e.g. Chzhen 2017), and mostly used a cross-sectional approach (e.g. Bárcena-Martín et al. 2017), this article analyses the role of different types of aggregate social spending to families, as well as their influence on child poverty over time and across European nations. By doing so, it helps to understand how the role and effectiveness of family policy to combat child poverty has changed during this period of economic turmoil and austerity.

The structure of this article is as follows. The next section is a literature review, in the third section the data, variables and methods are discussed, and in the final sections, the findings are presented and discussed.

2 Literature Review

Poverty is one of the oldest and most debated issues of social policy, and it refers to hardships and problems arising from an insufficiency of material recourses (Alcock 2006). Child poverty has been considered to be a more controversial problem than poverty in general, since children cannot choose their parents, and do not have control over their life circumstances (Bäckman and Ferrarini 2010). Furthermore, experiences of poverty in childhood may have important adult outcomes, potentially leading to an inter-generational transmission of disadvantages. For instance, children who have lived their first 5 years in a low-income family are more likely to drop out from school, to become teenage parents, to obtain inferior cognitive capacities, or to develop some kind of anti-social or criminal behaviour as older (e.g. Danziger and Waldvogel 2000; Esping-Andersen et al. 2002; Duncan et al. 1998). Consequently, the rising levels of child poverty across Europe during the financial crisis 2008–2009 and the subsequent recession (e.g. Chzhen et al. 2017; Chzhen 2017; Natali et al. 2014; Gornick and Jäntti 2012), has made this topic increasingly highlighted both on the political arena and in academia.

However, child poverty is a complex phenomenon that can be defined and measured in several ways. One problem is whether we should see it merely as a monetary problem, or as a problem of deprivation, insufficient participation or social exclusion (Bárcena-Martín et al. 2017; Gornick and Jäntti 2012; Chen and Corak 2008). The most common way of defining child poverty in high-income countries is to assess children’s ‘theoretical’ incomes based on their parents’ or the household’s disposable incomes by using a relative poverty threshold, such as the EU at-risk-of-poverty threshold. The reasons for this is that it facilitates international comparisons and is theoretically motivated since the general standard of living in a particular country is a relevant comparison point for most of its citizens (Bäckman and Ferrarini 2010, p. 283). However, relative income poverty should be understood primarily as a poverty risk, since it does not say much about the depth or duration of poverty (ibid.; Chen and Corak 2008; Laderchi et al. 2003). Accordingly, a growing literature stresses the importance of measuring child poverty multi-dimensionally, particularly in light of the UN Sustainable Development Goal 1, for example by using different indices on child deprivation (e.g. Bárcena-Martín et al. 2017) or juxtaposing relative measures of child poverty to anchored ones (e.g. Chzhen 2017). But also aggregated measurements of child poverty are important, since they facilitate comparative analyses and—as in the case of this article—allow a closer inspection of the significance of different spending strategies that welfare states undertake.

Previous research has found policy factors such as social spending to influence the level of child poverty. For instance, using the child module in the 2009 EU-SILC data, Bárcena-Martín et al. (2017) found that there is a strong and negative relationship between the level of social spending as a share of the GDP and child deprivation, after controlling for GDP per capita and unemployment. This study also found that while some of the general family benefits targeted at children did not reduce child deprivation, other benefits not explicitly targeted at children, such as housing benefits, did. In a similar study pooling different waves of the EU-SILC data (Chzhen 2017), the authors found social spending as a share of GDP to be negatively associated with both relative child poverty and anchored child poverty, although anchored child poverty did not produce significant correlations for the last 2 years in the study (2012 and 2013). Moreover, social spending was found to curb child poverty more efficiently in families with low work intensity and many children (ibid.). Similarly, Caminada et al. (2012) found that higher levels of social spending in relation to GDP were significantly and negatively associated with poverty after controlling for possibly intervening factors such as the unemployment rate and GDP per capita. This study did not, however, focus specifically on child poverty. Also studies focussing on single-parent households have shown that generous social transfers have a curbing effect on child poverty (e.g. Van Lancker et al. 2015; Chzhen and Bradshaw 2012). Furthermore, spending on universal transfers tend to be more effective than programs targeted to single parents (Brady and Burroway 2012). In a study combining LIS and SCIP data, Bäckman and Ferrarini (2010) found that family policy generosity and childcare coverage have a negative effect on the relative child poverty level, but that ‘dual-earner support alleviates poverty more effectively among single-mother households than support for more traditional gendered divisions of labour’ (Bäckman and Ferrarini 2010, p. 291; cf. Ferrarini 2006).

This finding is of particular interest for our study, since it suggests that different forms of family spending may work in different ways when it comes to child poverty reduction. Spending on family cash benefits (for example child benefits or maternity grants)—the ‘transfer-based’ strategy—focuses mainly on poverty reduction by redistributing incomes horizontally (between families with children and those without), or vertically (between different families with children) (Gauthier 2010; Wennemo 1994). On the other hand, spending on family benefits in kind (such as childcare)—the ‘service-based’ strategy—aims primarily at facilitating parental employment, which raises the household income and reduces the poverty risk (cf. Ferrarini 2006). Of course, child care and early education have also other important objectives, such as improving children’s future outcomes (e.g. Esping-Andersen 2005, 2009). Which strategy is more efficient for lifting households with children out of relative poverty is not clear. Some earlier studies (e.g. Bäckman and Ferrarini 2010; Ferrarini 2006) suggest that ‘service-based’ policies may be more effective poverty reducers than ‘transfer-based’ ones. This assumption is also supported by the comparative welfare state literature (e.g. Van Gerven and Nygård 2017; Hemerijck 2013),which shows that the ‘service-based’ strategy has become increasingly emphasised in policy making across Europe since the 1990s, not least by the European Union (for example in its Europe 2020 Agenda), and by other advocates of Social Investment ideas (e.g. Morel et al. 2012). But then again other studies show that ‘transfer-based’ policies are also important for child poverty reduction (e.g. Van Lancker et al. 2015; Chzhen and Bradshaw 2012; Brady and Burroway 2012). To our understanding, no previous studies have yet explicitly analysed the specific impact that public spending on family cash benefits and benefits in kind (including for example childcare services) have on child poverty, nor have they analysed how such spending programmes have developed over time in Europe, whereas there are several studies on the development in overall social spending and its role for child poverty (e.g. Chzhen et al. 2017; Ahrendt et al. 2015). This article aims at filling this void. However, the ‘transfer-based’ and ‘service-based’ strategies are not mutually exclusive. While ‘service-based’ policies are widely used for facilitating parental employment and investing in children, they are almost always coupled with different cash transfers that provide some modicum of income protection for families (Esping-Andersen 2005). Moreover, alongside parental employment and state transfers, the net market income received by households is also influenced by changes in growth rates and average real wage levels. In times of recession, the employment level generally drops, which means that children face higher poverty risks. On the other hand, growth and rising employment levels do not necessarily mean that new jobs, or higher work intensity, lead to lower poverty, since jobs are not always shared equally and have become increasingly concentrated to households with highly educated and employable adults (Corluy and Vandenbroucke 2015). This means that employment growth can in fact produce a static or increasing number of working-age households with no member in employment (De Graaf-Zijl and Nolan 2011).

Countries in Europe have used a mix of ‘transfer-based’ and ‘service-based’ policies. According to the family policy regime literature (Ferrarini 2006; Korpi 2000), countries in the ‘Nordic dual-earner regime’, such as Sweden and Finland, have generally invested heavily in services, but also in transfers to families. These countries display higher levels of female labour force participation and lower levels of child poverty than other countries. By contrast, countries in the ‘Continental regime’, such as Austria, France and Germany, have traditionally used a ‘transfer-based’ strategy relying on relatively generous cash benefits and tax credits, whereas spending on services (such as childcare services), has been low (Hemerijck 2013; Mahon 2002). More recently, however, many countries in this regime have also started to invest in ‘defamilising’ services, which has made them more similar to the Nordic ones and stimulated female (and maternal) employment, although child poverty levels have remained higher than in Nordic countries (Chzhen 2017; Ahrendt et al. 2015; Fagnani 2012; Esping-Andersen 2009). As to the countries in the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ market-based family regime, for instance the UK and Ireland, governments generally spend less on direct cash benefits to families, but more on tax subsidies for market-provided childcare services. This has not discouraged mothers from paid work, but made them prone to half-time rather than full-time employment (Esping-Andersen 2009). These countries have also displayed higher child poverty rates than Continental and Nordic countries (Campbell-Barr and Coakley 2014), although higher spending in the UK during the Labour regime resulted in a temporary downward trend in child poverty (Ahrendt et al. 2015; Daly 2010). In Mediterranean countries, where the male-provider norm has also been strong, family benefits have generally been modest and defamilising services almost non-existent with low levels of female employment and high poverty rates as a result (Ferrera 1996). However, in some countries, such as Portugal and Spain, there was a shift towards defamilising family policies, including higher childcare provision and higher family benefits, in the 1990s and early-2000s (Ahrendt et al. 2015; Guillén 2010). By contrast, Eastern European countries share a legacy of broad coverage of public social services from the communist era. They have also used a ‘transfer-based’ strategy, although the generosity level has been lower than in the Nordic and Continental countries (Saxonberg and Szelewa. 2007).

On the whole, the importance of the ‘service-based’ strategy seems to have grown since the 1990s, not least since politicians, social partners and governments across Europe have become increasingly susceptible to such influences (e.g. Nygård et al. 2015; Hemerijck 2013; Fagnani 2012). The European Union (e.g. European Commission 2010), as an example, has emphasised investments that have an expected future return in terms of for example higher education, better life chances for children and higher employment (Bonoli 2005). Parental employment plays a central role here, since it is seen as important for both sufficient incomes (and thus lower child poverty) and gender equality (Morel et al. 2012; Bonoli 2005; Esping-Andersen 2005; Esping-Andersen et al. 2002).

At the same time, we know that the financial crisis in 2008–2009 led to a period of falling growth and mounting fiscal challenges, which lasted longer in some countries than in others. This has made governments more prone to spending cuts for restoring fiscal balance. According to Farnsworth and Irving (2015) Europe entered a ‘new era of austerity’ around 2010–2011 making spending cuts the new order, even at the cost of deteriorating wellbeing of citizens and families (cf. O’Hara 2015; Blyth 2013). However, these cuts can be expected to have curtailed spending on cash benefits—including cash benefits to families—to a higher extent than spending on services, since the latter is more protected by its saliency in the Social Investment Strategy (Heise and Lierse 2011; Morel et al. 2012). Moreover, the cuts did not generally become visible until 2009–2011, since most countries increased their cash benefits to families during the first phase of the crisis (Ahrendt et al. 2015; Richardson 2010; Gauthier 2010).

We can sum up this discussion by stating that both transfers and services play a role for child poverty reduction, although their relative impact is still somewhat unclear. We can also see a stronger political emphasis on the ‘service-based’ strategy since the 1990s, which is likely to have increased the level of public spending on family services during the 2000s. Moreover, the mix of family transfers and services across European countries, and especially the increasing emphasis of the ‘service-based’ strategy, has resulted in changing patterns of defamilisation (Lohmann and Zagel 2016) and has blurred the traditional differences between ‘classical’ family policy regimes (cf. Thévenon 2011; Saxonberg and Szelewa 2007; Mahon 2002).

This brings us to a number of hypotheses. First, due to the increasing political emphasis on service-based strategies across Europe (Hemerijck 2013), we expect spending on cash benefits and services to have increased during the first phase of the crisis, but to have diverged after 2009–2011 so that spending on services have continued to climb whereas spending on cash benefits have flattened out or decreased (H1). Second, due to their capacity to foster parental employment and to increase the total household income (cf. Bäckman and Ferrarini 2010; Ferrarini 2006), we expect public spending on in-kind benefits to be more strongly and negatively correlated with child poverty than spending on cash benefits, when controlling for employment factors, the general living standard and welfare state configurations (H2). Third, we expect the negative correlations between child poverty and the two forms of family spending to have weakened over the 2006–2015 period due to recurrent cuts and higher unemployment (H3).

3 Data, Variables and Methods

3.1 Data

We used aggregated data on child poverty from the EU-SILC survey (Eurostat 2017a) and data on public social spending from the OECD SOCX database (OECD 2019) for 22 European countries and 10 years (2006–2015).Footnote 1 The countries included were Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and the UK. These countries were selected, since they represent different family policy regimes and were the only ones for which we could obtain data on all variables and years. The use of aggregated data was motivated by the fact that we primarily sought to study the role of different family spending for child poverty, as a number of studies have shown these to be of importance alongside factors on the household and individual level (e.g. Chzhen 2017; Bárcena-Martin et al. 2014; Dewilde 2008; Muffels and Fourage 2004).

3.2 Variables

The outcome variable, Child poverty, was measured as the share of persons under 18 years with an equivalised disposable income below the risk-of-poverty threshold, which is set at 60% of the national median equivalised disposable income (after social transfers) (Eurostat 2017a). Although this is a widely used indicator child poverty, it suffers from some problems. For instance it focuses solely on monetary poverty and disregards aspects of deprivation and exclusion (Bárcena-Martín et al. 2017). Moreover, it fails to discriminate poverty in different households, since it contains no information as to what kind of household children live in (Chzhen 2017). It can nevertheless be justified since it is considered a relevant measure in international comparisons (Bäckman and Ferrarini 2010).Footnote 2

As independent variables we used Public expenditures on family cash benefits in relation to GDP (CASCHBENEFITS) and Public expenditures on family benefits in kind in relation to GDP (INKINDBENEFITS) for the years 2006–2015 (OECD 2019).Footnote 3 Although the use of social spending in relation to GDP is somewhat problematic, and warrants controls of real GDP levels and change, it is a widely used technique for assessing ‘welfare state effort’ (e.g. Clasen and Nico 2007) and is thus suitable for testing different welfare state efforts to curb child poverty.

The control variables measure the impact of family structure, labour markets, economic growth, standards of living, as well as welfare state configurations. Single-parent households (SINGLE) measures the share of children living with a sole provider (OECD 2017). Multi-child families (MULTICHILD) stands for the share of households with four of more children under 18 years (Eurostat 2017b).Footnote 4Female labour participation (FEMLABOUR) relates to the labour participation rate (%) of all working-age women (ILO 2017). Unemployment rate (UNEMPLOYMENT) represents the number of unemployed persons as a percentage of the labour force based on the International Labour Office (ILO) definitionFootnote 5 (Eurostat 2017c). Annual data on GDP per capita (GDPCAPITA), and GDP change (GDPCHANGE) was obtained from Eurostat (2017d, e) in order to control for the general living standard and economic development. This is important, since we study spending as a share of GDP. Moreover, the child poverty rate is generally lower in rich countries (Chzhen 2017). In order to control for the role of different welfare-institutional configurations, we included dummy variables for different family policy regimes (NORDIC, CONTINENTAL, ANGLO-SAXON, and EASTERN EUROPEAN) using the Mediterranean regime as reference. Finally, a dummy variable [TIME2 (2009–2011), TIME3 (2012–2015)] was included for controlling for the effect of change in time using the pre-crisis time period (2006–2008) as reference.

3.3 Analyses

We performed descriptive statistics for testing H1 on the changes in family spending on cash benefits and benefits in kind, both in relation to GDP and in real terms. For testing H2, we performed pooled cross-section time-series OLS regressions with robust standard errors of child poverty on the two types of spending for the whole 2006–2015 period. For testing H3, we used year-specific OLS regressions that both compared the coefficients for the two spending types with each other and analysed how the associations between child poverty and the two types of spending changed overt time.

The pooled cross-section time-series OLS regression used a balanced panel of 22 countries and 10 years, yielding a total N of 220 observations. This technique maximizes the number of observations, but is also very sensitive for biases resulting from the error term (Kittel and Winner 2005; Beck and Katz 1995). Preliminary analyses indicated no significant biases related to autocorrelation (AR1) or panel-level heteroscedasticity, which suggested that the use of a linear regression model with panel-corrected standard errors of child poverty on the two spending variables (and control variables), was applicable (Beck and Katz 1995). We used the XTPCSE command in STATA 14, which allows the standard errors to be consistent when the disturbances from each observation is not independent (Stata 2012). However, we also ran the same regressions with an alternative technique for panel analysis (XTGLS), which produces more efficient estimates of the parameters, but with the disadvantage that the standard errors are conditional on the estimated disturbance covariance (Stata 2012). The XTGLS analyses produced more or less similar coefficients with similar signs as the XTPCSE ones, but with higher standard errors. In order to check the robustness of using spending data (as a percentage of GDP), we also conducted similar regressions of child poverty as we did for testing H2 by using alternative public family spending data (i.e. spending per capita, in current prices and current PPPs, USD, as well as spending as a percentage of total government spending from the OECD SOCX data base.

4 Findings

Figure 1 shows an overall upward trend in child poverty for the 22 countries over the studied period. In 2006, the average rate was 15.4% whereas it had climbed to 16.1% in 2015. The EU27 average is somewhat higher than for our selected countries, since some countries with high child poverty rates, such as Romania or Bulgaria, were not included in our sample. The findings corroborate earlier results by Chzhen et al. (2017) and Natali et al. (2014), and shows that the share of children living in poor households increased during the period of the financial crisis. Yet the increase remains rather modest, which suggests that European welfare states were relatively successful in protecting their families from poverty (Ahrendt et al. 2015).

The change in child poverty 2006–2015, averages (arithmetic mean) for the 22 studied countries compared to the EU 27 mean (Eurostat 2017a). The figure displays the share (%) of persons under 18 living in households with an equivalised disposable income below the risk-of-poverty threshold, which is set at 60% of the national median equivalised disposable income (after social transfers)

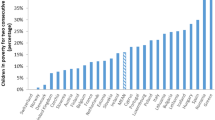

However, these crude averages hide considerable variation between countries and family policy regimes, which can be seen from Fig. 2a–e. In the Nordic countries, the poverty rates stay well below the EU27 average for the whole period, although Sweden experienced a somewhat steeper rise than Finland and Denmark. Also Continental countries stay under the EU27 average, although there is more variation and an upward trend, with the most noticeable rises in Luxembourg and Germany. Anglo-Saxon countries clustered close to the EU27 average. The poverty rates dropped from somewhat higher initial levels until 2011 where after they started to climb again, although not in a dramatic manner. The Mediterranean countries all stay above the EU27 average for the whole period and display an upward trend in child poverty, with a pronounced rise in Greece between 2011 and 2013 and in Spain between 2013 and 2014. In the Eastern European cluster, finally, the variation in child poverty is considerable, with Latvia, Estonia and Poland above the EU27 average for almost the whole period, and the rest of the countries well below this average. There is an upward trend, except for Poland and the Czech Republic, with some noticeable rises in Estonia, Latvia and Hungary. On the whole, these findings show that child poverty has increased in Europe during the time of crisis, but we also see major differences between country clusters, with Nordic countries displaying the lowest and Mediterranean countries the highest poverty rates.

a–e The change in child poverty 2006–2015 in different family policy regimes as compared to the EU 27 mean (Eurostat 2017a): a refers to the Nordic, b to the Continental, c to the Anglo-Saxon, d to the Mediterranean and e the Eastern European regime. The figure displays the share (%) of persons under 18 living in households with an equivalised disposable income below the risk-of-poverty threshold, which is set at 60% of the national median equivalised disposable income (after social transfers)

This also lends support to the family policy regime literature (e.g. Ferrarini 2006; Korpi 2000), although it seems evident that Eastern European countries might in fact be divided into two separate regimes, one including the Visegrad countries and Slovenia, the other including the Baltic countries. The explanations to the observed variation in the outcome variable are most likely be found in factors such as economic growth, unemployment, family structures, family policy generosity and labour market structure (Chzhen 2017; Bárcena-Martin et al. 2014; Bäckman and Ferrarini 2010; Dewilde 2008; Muffels and Fourage 2004).

We will therefore turn our attention to one of the policy factors in this equation, namely public social spending, and its relation association with child poverty. We will start with our first research question and assess changes in spending over time. As shown in Fig. 3a, there is an overall upward trend in the development of average public spending on family cash benefits in relation to GDP, and it has remained on a higher level than spending on in-kind benefits for the whole period. It climbed in a noticeable way until 2009, but then started to drop and flatten out. By contrast, the average level of spending on in-kind benefits has remained more stable, but also here slight up-ward trend is detectable, although the level dropped somewhat after 2013.

a, b The development of average public expenditures on family cash benefits and family in-kind benefits in 22 European countries 2006–2015 (OECD 2019). a Expenditures as a percentage of GDP. b Real expenditures (billion USD)

However, since spending as a share of the GDP suffers from the obvious problem that it can appear to go up at times of falling absolute GDP, we need to check also for changes in real spending. As shown in Fig. 3b, the average spending on cash benefits climbed markedly until 2009, then flattened out, and then started to climb again after 2012. By contrast, real spending on in-kind benefits has grown in a steady pace. These findings support H1 that spending on cash benefits has developed in a different way than spending on in-kind benefits. One reason for this is that most European governments started to contain their spending on cash benefits around 2009, and ‘froze’ the levels until 2012, when an upward adjustment became possible due to economic recovery (in some countries) (cf. Farnsworth and Irving 2015). This is not the case with spending on in-kind benefits that have increased in a steady pace over the period, suggesting a more stable inclination to use the ‘service-based’ strategy throughout the 2006–2015 period in accordance with the Social Investment Strategy advocated by the European Union (e.g. European Commission 2010).

A country-specific analysis (not reported) of the development of spending on cash benefits over time shows no major changes in relative (to GDP) or real spending patterns for the Nordic countries. Meanwhile, all the other countries (except for Belgium) lowered their relative spending levels after 2009, and most drastically so in Luxembourg and Latvia. However, after 2011–2013, some countries (Poland, Latvia, Greece and Italy) made some increases in their relative spending. In terms of real spending on cash benefits, the overall trend is more stable and shows a slight increase over time, but with sharp increases in Germany, Italy, Spain, Poland and the Netherlands after 2012–2013, whereas there was a drastic drop in the UK after 2013.

A country-specific analysis (not reported) of the development of (relative and real) spending on in-kind benefits shows a slight upward trend in relative spending until 2012–2013, when it starts to drop, except for Germany, France, Latvia, Poland and Italy where the upward trend is stable and even displays some drastic increases after 2013 (Latvia and Italy). In the Netherlands there was a sharp drop 2007, then a stabilization between 2008 and 2010 that shifted to a slow decrease. In terms of real spending, there is an overall and stable upward trend for the 2006–2015 period (except for the Netherlands), with drastic increases in France, Germany, and more moderate increases in the UK (until 2013), Italy (after 2013) and Poland (since 2007). On the whole, these findings support H1 by showing that public spending on benefits in kind has increased in more stable fashion than cash spending, and that formerly ‘transfer-oriented’ countries, such as France, Germany and Italy, have increased their investments in services in the 2000s (Hemerijck 2013; Fagnani 2012). However, we cannot find evidence of a shift from a ‘transfer-based’ to a ‘service-based’ strategy. Instead both strategies have continued to coexist, albeit with different pronunciations in different countries.

Let us now turn to the second research question relating to the poverty-reducing efficiency of different forms of family spending. We expected that spending on in-kind benefits would be more strongly and negatively correlated with child poverty over the 2006–2015 period than spending on cash benefits, when controlling for employment factors, the general living standard and welfare state configurations (H2). Table 1 shows standardized β-coefficients, panel-corrected standard errors and levels of statistical significance from pooled OLS regressions of child poverty on public spending on cash transfers and benefits in kind, respectively, while controlling for factors pertaining to family structure, the general standard of living, the labour market and welfare-institutional characteristics (cf. Ferrarini 2006). Model 1 estimates the association between spending on cash benefits (relative to GDP) and child poverty. Model 2 includes controls for family, labour-market factors, affluence, and economic growth. Model 3 includes controls for family policy regimes (dummy variables with the Mediterranean model as reference). Models 4–6 assess the role of spending on in-kind benefits according to a similar logic. Models 7–9 analyse the role of both cash and in-kind spending for child poverty.

As expected from previous research (e.g. Chzhen 2017; Bárcena-Martin et al. 2014; Ferrarini 2006), both cash benefit and in-kind spending are negatively and significantly correlated with child poverty. However, the impact of spending on in-kind benefits is consistently stronger than spending on cash benefits, even when controlling for other variables and inserting the two independent variables simultaneously (models 7–9). This result supports H2 and is likely to stem from its capacity to cater for a dual earner model and thus to produce higher parental employment rates and a higher overall income level for households (Ferrarini 2006). Not surprisingly, the share of children in single-provider households and the unemployment level is positively and significantly associated with child poverty, while the female employment rate displays a negative association (cf. Chzhen 2017; Bárcena-Martin et al. 2014; Bäckman and Ferrarini 2010; Ferrarini 2006; Dewilde 2008). However, that large families seem to constitute a poverty-reducing factor is somewhat surprising, since earlier research has revealed this as a poverty risk factor (e.g. Ahrendt et al. 2015). This unexpected result might depend on the way that the variable was operationalized (the share of families with four or more children) and be conditioned by incomes. To have four children or more might in fact be more common among better-off families with more economic resources to support children. For instance, previous research has shown that highly educated women, who also tend to have higher incomes, are likely to find a larger number of children as desirable (Testa 2014). The association however becomes insignificant when controlling for welfare state affiliation. Expectedly, the time dummies show stronger and positive coefficients for Time 3 than previous periods, which is in line with Fig. 1 suggesting a somewhat sharper increase in child poverty since 2013.

However, with the data at hand, we cannot say anything about the impact of public spending on different households. Furthermore, this is something that works in different ways in different family policy regimes, which we can see from the inclusion of regime dummies in models 3, 6 and 9. Spending on cash benefits seems to reduce child poverty more effectively in the Nordic and Continental countries than in others, which may have to do with the level of generosity and universal provision of child benefits (Van Lancker et al. 2015; Brady and Burroway 2012; Fagnani and Math 2008). This is also true for spending on benefits in kind (model 6), but here the Continental model takes the lead before the Nordic model.

In order to check the robustness of the analysis we also performed similar regression models as in Table 1, but with alternative spending data (spending per head, in current prices and current PPPs, USD, as well as spending in relation to total government expenditure) for the two independent variables (not reported due to limited space, but available upon request). When using these alternative measurements, the coefficients for the two independent variables became much weaker and lost their significance when control variables were inserted. However, the signs of the coefficients remained more or less the same, with stronger negative β coefficients for spending on benefits in kind, even after inserting control variables. This suggests robustness in the relation between the two types of spending (in-kind spending is more strongly and negatively correlated with child poverty than spending on cash benefits). However, it also shows that the importance of public spending for child poverty diminishes radically in relation to structural factors (such as the unemployment level or the number of single-parent households) when we use spending in relation to total government spending, and even more so if we use spending per head.

What can then be said about the poverty-reducing capacity of cash and in-kind spending over time (H3)? Since we cannot assess this from Table 1, a more detailed, year-by-year, analysis of the association between child poverty and the two spending types needs to be conducted. This also allows a comparison of the regression coefficients for the two forms of spending over time. Table 2 shows year-specific β-coefficients from OLS regression models of child poverty on cash and in-kind public spending for the 22 European countries.

As expected, the coefficients for spending on in-kind benefits are negative and consistently stronger than for cash benefits, even when controlling for other variables. There is also a gradual downward trend in the strengths of both coefficients as well as in the R Squares over time, which supports H3 by indicating that both forms of spending have become less efficient in reducing poverty over the studied period, but that spending on benefits in kind have remained more effective for curbing child poverty, even when inserting control variables (Model 4). This result can at least partly be attributed to higher unemployment of parents and a lower up-take rate of services (such as childcare services), as well as to cuts in the generosity of cash transfers to families (see e.g. Taylor-Gooby et al. 2017; Ahrendt et al. 2015).

5 Conclusions and Discussion

This article set out to investigate different forms of public spending on families and their role for child poverty during a period of economic turmoil. Based on the findings, a number of conclusions can be drawn. First, all countries have used both a ‘transfer-based’ and ‘service-based’ strategy, with different pronunciations across regimes (Ferrarini 2006). In the Nordic, Anglo-Saxon and Eastern European countries, both strategies have been central, although spending and generosity levels have varied across countries. By contrast, Continental and Mediterranean countries have primarily used a ‘transfer-based’ strategy, with Continental countries spending levels exceeding those in other countries. However, during the 2000s countries in the Continental and Mediterranean regimes have increasingly invested in childcare services (Fagnani 2012), which questions the relevance of the family policy regime model suggested by Korpi (2000).

Second, the two forms of family spending have developed in different ways over the studied period, with a more stable growth in (both relative and real) spending on in-kind benefits, whereas the development of cash benefits spending shows traces of cost containments. In the initial phase of the crisis, most countries responded to growing poverty by expanding their spending on family cash benefits, but soon also cost containment measures set in (Farnsworth and Irving 2015; Gauthier 2010). This is not the case with spending on benefits in kind, at least not to the same extent. This suggests that ‘service-based’ policies have grown more influential across Europe in line with the Social Investment Strategy (European Commission 2010), while ‘transfer-based’ policies have been subjected to cost containment to a higher extent. However, we cannot speak of any ‘shift’ from one strategy to another, since both strategies have continued to grow and co-exist, which is also to be expected taking into consideration that they are mutually dependent in many ways (Esping-Andersen et al. 2002; Esping-Andersen 2005).

Third, spending on in-kind benefits to families seems to be a more effective way of combating child poverty than spending on cash benefits, even when controlling for other variables and juxtaposing both spending variables in the same regression models. This is also true when we use alternative spending measures (family spending per head, family spending as a percentage of total government spending), although the coefficients are much weaker for these models. The results support previous findings (Ferrarini 2006) and suggest that public spending on benefits in kind facilitate parental employment, which in turn has a stronger impact on the total household income than spending on cash benefits has. This corresponds to the ideas of the Social Investments Strategy (e.g. Morel et al. 2012; Esping-Andersen 2005), but also to the ideas of an ‘activating’ social policy, which has emphasised the supremacy of paid work when it comes to poverty reduction and has prioritized ‘welfare-to-work’ benefits over ‘passive’ social protection (Hemerijck 2013). We need to remember, though, that our analysis cannot say anything in detail about what kind of poverty (e.g. single-parent poverty, in-work poverty etc.) spending curbs most, since we use aggregated data with a relative poverty risk threshold as our outcome variable. It may be that spending on benefits in kind has a stronger poverty-reducing impact on single-parent households than on families with two adults (cf. Bäckman and Ferrarini 2010), but we cannot assess this with the data at hand. Therefore future research needs to go deeper into how different spending influences different kinds of poverty as well as deprivation by using for example EU-SILC data and multi-level methods. Also future research needs to involve the role of private spending, especially when it comes to benefits in kind.

Fourth, both public spending on family cash benefits and on benefits in kind has become less efficient in combating child poverty during the studied period, although spending on benefits in kind has retained its stronger poverty-curbing function. This is likely be a result of higher unemployment, cuts in family transfers and lower childcare uptake (Chzhen et al. 2017; Chzhen 2017).

Fifth, the results from the control analyses with alternative spending data show that the role of public spending on child poverty is dependent upon how spending is measured. The relative impact of public spending on child poverty becomes weaker in comparison to structural factors (such as the unemployment level or number of single-parent households) when using spending in relation to total government spending, and spending per head in particular. However, spending on in-kind benefits still remain more strongly and negatively correlated with child poverty than spending on cash benefits. Which spending measure gives a more ‘true’ picture can be debated, but clearly spending as a percent of GDP gives policy factors a more ‘optimistic’ role than other spending measures do. This article suffers from a number of limitations. First, aggregated spending data does not say anything about the generosity of family policy. It only allows a crude estimate of country-level policy effort. Nonetheless, it can still help to understand how different types of spending on families have changed over time and how they are related to child poverty. Second, further analyses are warranted in order to understand how different forms of family spending influences different families at the household level, such as single-parent families compared to dual-earner families.

Finally, some policy implications emanate from the study. First, it highlights the importance of family services as a poverty-reducing tool, since we found public spending on benefits in kind to be more strongly and negatively correlated with child poverty. However, this does not in any way rule out the importance of cash benefits, especially for households without working parents. Second, it shows that cuts in spending on families with children come with a high price, since they do not only have consequences for the here-and-now lives of children, but also for their future life prospects (cf. O’Hara 2015). Thirdly, the results show that different measures of public spending produce different accounts of the relative role of policy for child poverty as compared to the role of structural factors, for example the role of unemployment. Since public spending on families in relation to GDP tends to produces a rather ‘optimistic’ account of the role of policy for poverty, we need to take that into consideration when evaluating different assessments of policy efficiency in this field.

Notes

To date, the OECD SOCX database provides data on family expenditures for these 22 countries until 2015.

The choice of this indicator was also motivated by the fact that it was the only one for which we could obtain data for all countries and years included in the analysis.

Public spending on family cash benefits refers to child benefits and other income transfers to families with children. Public spending on family benefits in kind refers to public spending on services for families with children, including childcare, ECEC, public childcare support, assistance, family services and home help (OECD 2019).

The reason for including this indicator is that multi-child households have proved to be under higher risk of child poverty (e.g. Ahrendt et al. 2015). However, since we could not find data for households with three or more children, which is the most common way, we chose to use data on households with four or more children instead.

The labour force refers to the total number of people employed and unemployed aged 15 to 74 (Eurostat 2017c).

References

Ahrendt, D., Blum, S., & Crepaldi, C. (Eds.). (2015). Families in the economic crisis: Changes in policy measures in the EU. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Alcock, Pete. (2006). Understanding poverty (3rd ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bäckman, O., & Ferrarini, T. (2010). Combating child poverty? A multilevel assessment of family policy institutions and child poverty in 21 old and new welfare states. Journal of Social Policy,39(2), 275–296.

Bárcena-Martín, E., Blázquez, M., Budría, S., & Moro-Egido, A. (2017). Child deprivation and social benefits: Europe in cross-national perspective. Socio-Economic Review,15(4), 717–744.

Bárcena-Martin, E., Lacomba-Arias, B., Moro-Egido, A., & Pérez-Moreno, S. (2014). Country differences in material deprivation in Europe. Review of Income and Wealth,60(4), 802–820.

Beck, N., & Katz, J. N. (1995). What to do (and not to do) with time-series cross-section data. American Political Science Review,89(3), 634–647.

Blyth, M. (2013). Austerity: The history of a dangerous idea. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bonoli, G. (2005). The politics of the new social policies. Providing coverage in new social risks in mature welfare states. Policy and Politics,33(3), 431–449.

Brady, D., & Burroway, R. (2012). Targeting, universalism, and single-mother poverty; a multilevel analysis across 18 affluent democracies. Demography,49(2), 719–746.

Caminada, K., Goudswaard, K., & Koster, F. (2012). Social Income transfers and poverty: a cross-country analysis for OECD countries. International Journal of Social Welfare,21(2), 115–126.

Campbell-Barr, V., & Coakley, A. (2014). Providing choice? A comparison of UK and Ireland’s family support in a time of austerity. Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy,30(2), 231–244.

Chen, W. H., & Corak, M. (2008). Child poverty and changes in child poverty. Demography,45(3), 537–553.

Chzhen, Y. (2017). Unemployment, social protection spending and child poverty in the European Union during the Great Recession. Journal of European Social Policy,27(2), 123–137.

Chzhen, Y., & Bradshaw, J. (2012). Lone parents, poverty and policy in the European Union. Journal of European Social Policy,22(5), 487–506.

Chzhen, Y., Nolan, B., Cantillon, B., & Handa, S. (2017). Impact of the economic crisis on children in rich countries. In B. Cantillon, Y. Chzhen, S. Handa, & B. Nolan (Eds.), Children of austerity. Impact of the great recession on child poverty in rich countries (pp. 8–29). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clasen, J., & Nico, A. S. (Eds.). (2007). Investigating welfare state change: The ‘Dependent Variable Problem’ in comparative analysis. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Commission, European. (2010). Europe 2020: A European strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. Brussels: Communication from the Commission.

Corluy, V., & Vandenbroucke, F. (2015). Polarisation of employment over households revisited: The Belgian case. Discussion Paper Series/KU Leuven, Center for Economic Studies, DPS15.08. Leuven: KU Leuven, Center for Economic Studies

Daly, M. (2010). Shifts in family policy in the UK under New Labour. Journal of European Social Policy,20(5), 433–443.

Danziger, S., & Waldvogel, J. (2000). Securing the future. Investing in children from birth to college. New York: Russell Sage.

De Graaf-Zijl, M. & and Nolan, B. (2011). GINI DP 5: Household joblessness and its impacts on poverty and deprivation in Europe. GINI Discussion Paper 5. Amsterdam: AIAS.

Dewilde, C. (2008). Individual and institutional determinants of multidimensional poverty: A European comparison. Social Indicators Research,86(2), 244–256.

Duncan, G. J., Brooks-Gunn, J., Yeung, W. J., & Smith, J. R. (1998). How much does childhood poverty affect the life changes of children? American Sociological Review,63, 406–423.

Esping-Andersen, G. (2005). Children in the welfare state. A social investment approach. DemoSoc working paper, 2005:10. Barcelona: Univesitat Pompeu Fabra.

Esping-Andersen, G. (2009). Incomplete revolution: Adapting welfare states to women’s new roles. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Esping-Andersen, G., Gallie, D., Hemerijck, A., & Myles, J. (2002). Why we need a new welfare state. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Eurostat. (2017a). Incomes and living conditions, monetary poverty, at-risk of poverty rate by poverty threshold, age and sex (EU-SILC survey ilc_li02). http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/refreshTableAction.do?tab=table&plugin=1&pcode=tessi120&language=en. Accessed June 2017.

Eurostat. (2017b). Distribution of households with children by number of children—EU-SILC survey [ilc_lvph05]. http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do. Accessed 13 June 2017.

Eurostat. (2017c). Unemployment rate—Annual data. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=tipsun20&plugin=1. Accessed 3 May 2017.

Eurostat. (2017d). Real GDP per capita. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&plugin=1&pcode=sdg_08_10&language=en. Accessed 14 September 2018.

Eurostat. (2017e). Real GDP growth rate. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=tec00115&plugin=. Accessed 14 September 2018.

Fagnani, J. (2012). Recent reforms in childcare and family policies in France and Germany: What was at stake? Children and Youth Services Review,43(3), 509–516.

Fagnani, J., & Math, A. (2008). Family packages in 11 European countries. In C. Saraceno & A. Leira (Eds.), Childhood: Changing contexts (pp. 55–78). Bingley: Emerald, JAI.

Farnsworth, K., & Irving, Z. (2015). Austerity: More than the sum of its parts. In K. Farnsworth & Z. Irving (Eds.), Social policy in times of austerity (pp. 9–21). Bristol: The Policy Press.

Ferrarini, T. (2006). Families, states and labour markets. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Ferrera, M. (1996). The ‘southern’ model of welfare in social Europe. Journal of European Social Policy,6(1), 17–37.

Gauthier, A. H. (2010). The impact of the economic crisis on family policies in the European Union. Brussels: European Commission.

Gornick, J. C., & Jäntti, M. (2012). Child Poverty in cross-national perspective: Lessons from the Luxembourg Income Study. Children and Youth Services Review,34(3), 558–568.

Guillén, A. (2010). Defrosting the Spanish welfare state: The weight of conservative components. In B. Palier (Ed.), A long goodbye to Bismarck? (pp. 183–206). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Heise, A., & Lierse, H. (2011). The effects of european austerity programmes on social security systems. Modern Economy,2, 498–513.

Hemerijck, A. (2013). Changing welfare states. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

ILO. (2017). Labour force participation rate—ILO modelled estimates, July 2015. http://www.ilo.org/ilostat/. Accessed 8 May 2017.

Kittel, B., & Winner, H. (2005). How reliable is pooled analysis in political economy? The globalization-welfare state nexus revisited. European Journal of Political Research,44(2), S269–S293.

Korpi, W. (2000). Faces of inequality: Gender, class, and patterns of inequalities in different types of welfare states. Social Politics,7(2), 127–191.

Laderchi, C. R., Saith, R., & Stewart, F. (2003). Does it matter that we do not agree on the definition of poverty? A comparison of four approaches. Oxford Development Studies,31(3), 243–274.

Lohmann, H., & Zagel, H. (2016). Family policy in comparative perspective: The concepts and measurement of familization and defamilization. Journal of European Social Policy,26(1), 48–65.

Mahon, R. (2002). Child care: Toward what kind of ‘Social Europe’? Social Politics,9(3), 343–379.

Morel, N., Palier, B., & Palme, J. (2012). Beyond the welfare state as we knew it? In N. Morel, B. Palier, & J. Palme (Eds.), Towards a social investment welfare state? (pp. 1–32). Bristol: Policy Press.

Muffels, R., & Fourage, D. (2004). The role of European Welfare States in explaining resource deprivation. Social Indicators Research,68(2), 299–330.

Natali, L., Handa, S., Chzhen, Y., Martorano, B., Bitler, M. Hoynes, H., & Kuka, E. (2014). Changes in Child Poverty in the OECD/EU during the Great Recession: An initial view. Innocenti Working Paper No. 2014-16. UNICEF Office of Research, Florence.

Nygård, M., Kuisma, M., Krüger, N., & Campbell-Barr, V. (2015). Investing in our future? The influence of social investment ideas on family policy discourses in Finland, Germany and the UK. In U. Korkut, K. Mahendran, & G. Bucken-Knapp (Eds.), Discursive governance in politics, policy, and the public sphere (pp. 31–46). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

O’Hara, M. (2015). Austerity Bites: A journey to the sharp end of cuts in the UK. Bristol: Policy Press.

OECD. (2017). Proportion of children (%) aged 0–17 living with a sole parent. Retrieved May 8, 2017 from http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=FAMILY.

OECD. (2019). Social expenditure. Aggregated data. https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?datasetcode=SOCX_AGG. Accessed 21 February 2019.

Richardson, D. (2010). Child and family policies in a time of economic crisis. Children and Society,24(2010), 495–508.

Saxonberg, S., & Szelewa, D. (2007). The continuing legacy of the communist legacy? The development of family policies in Poland and the Czech Republic. Social Politics,14(3), 351–379.

STATA. (2012). Longitudinal/panel data. Lakeway drive, Texas: Stata Press. https://www.stata.com/manuals13/xtxtpcse.pdf. Accessed 21 Feb 2019.

Taylor-Gooby, P., Leruth, B., & Chung, H. (Eds.). (2017). After austerity. Welfare state transformation in Europe after the great recession. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Testa, M. R. (2014). On the positive correlation between education and fertility intensions in Europe: Individual- and country-level evidence. Advances in Life Course Research,21, 28–42.

Thévenon, O. (2011). Family policies in OECD countries: A comparative analysis. Population and Development Review,37(1), 57–87.

Van Gerven, M., & Nygård, M. (2017). Equal treatment, labor promotion, or social investment? Reconciliation policy in Finnish and Dutch Coalition Programs 1995–2016. European Policy Analysis,3(1), 125–145.

Van Lancker, W., Ghysels, J., & Cantillon, B. (2015). The impact of child benefits on single-mother poverty: Exploring the role of targeting in 15 European countries. International Journal of Social Welfare,24(3), 210–222.

Wennemo, I. (1994). Sharing the costs of children. Studies in the development of family support in the OECD countries. Swedish Institute for Social Research 25. Stockholm: University of Stockholm.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Abo Akademi University (ABO).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Nygård, M., Lindberg, M., Nyqvist, F. et al. The Role of Cash Benefit and In-Kind Benefit Spending for Child Poverty in Times of Austerity: An Analysis of 22 European Countries 2006–2015. Soc Indic Res 146, 533–552 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02126-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02126-8