Abstract

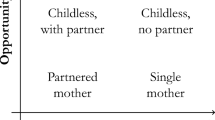

Empirical studies have consistently documented that while married men tend to lead more prosperous careers after moving, migration tends to be disruptive for careers of married women. We extend this literature by exploring whether migration is followed by a change in subjective wellbeing (SWB). We examine how this experience differs by individuals of different gender, relationship-status and motivations for moving (of both partners in a couple relationship, where relevant). The results are compared to wage differences following migration. All results are conditioned on time-varying personal characteristics, including important life events. Consistent with prior literature, males have a stronger tendency than females to increase their earnings after moving. However, we find that females have a stronger tendency than males to increase their SWB following a move. These gender differences are pronounced for couples. Differences tend to narrow, but do not disappear, once we account for motivations for moving of individuals and, where relevant, of their partner.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Much of the existing literature has focused on married couples. In this study, we extend the focus to de-facto couples.

The only study we can find which has acknowledged relationship-status in examining SWB outcomes of migration by gender is Nowok et al. (2013), but this aspect is not the focus of their study. The authors mention that they find that females migrating with their partners do not experience significantly different SWB outcomes of internal migration to their partners. However, they do not present these results.

We drop observations of individuals who are never observed to move but are not observed in all periods, because they could have moved in unobserved years.

We also explore effects of migration on hourly wage rates and hours worked.

Individuals who change couple-status or who change partner around migration are dropped from our analysis. We also control for actual couple-status (which may change in years prior to or following migration).

So that we can interpret coefficients as deviations from the baseline year, we also control separately for migrant couple-status. It is not necessary to do this for gender since gender does not vary over time for any individual in our sample and so is already accounted for by the individual fixed effects.

The year of migration is defined as the period in which a person is observed to have moved since the previous wave.

We also drop migrants who change partner from the period observed before migration to the period after.

\( Migrant Couple_{i,t - l } \) is constant for observations of the same migrant relating to a particular move, but it is time-varying because individuals can migrate more than once and may be in a different relationship-status across different moves. The treatment of migrants who move multiple times is described below.

\( Gender_{i} \) is separately controlled for in the individual fixed effects.

Our definition of moving here is consistent with the definition elsewhere in the paper being a move of at least 25 km.

We do not focus on very short distance migration because we are interested in decisions which involve a change in earnings potential and amenities. 25 km is the threshold used by Nowok et al. (2013) for long-distance migration.

Specifically, we drop observations in which anyone is in the armed services. For non-migrants, we drop all observations of individuals ever in the armed services.

In addition, we drop 18 observations of individuals who are identified as living in a couple but whose marital status is ‘never married/not divorced’.

Because self-reported health is missing for a large number of observations, we do not drop these individuals but rather include missing health information as one of the categories of the variable.

The reasoning here is that if there is missing information between two observations, we cannot be sure that there has been no change in location in the missed year.

There are fewer than 14 observations for some non-migrants because they are dropped in waves in which they are outside the age range of 25-60 years old or when they are missing data on some variables.

The reason for this requirement is to avoid age distortions, since the male partner tends to be older than the female partner for couples in our sample.

This figure adds to more than the total of 2099 individuals who migrate because some migrants make both a short distance and a long-distance move throughout the sample period.

This question is asked in HILDA after the survey has just finished asking about particular aspects of one’s life. The survey first asks about peoples’ satisfaction with their health, family relationships, employment, etc. Hence it is natural to suppose that people answer the aggregate life satisfaction question in a way that reflects the totality of their circumstances.

The categories that we group to reflect work-related reasons are “to start a new job with a new employer”; “to be nearer place of work”; “work transfer”; “to look for work”; or other “work reasons”.

Only reasons which were reported by at least 5% of migrants are reported. Individuals could report multiple reasons.

In these and all subsequent regression tables, dummies for the years around migration are represented by before4, before3, before2 for 4, 3, and 2 years before migration, respectively, migrant for the year of migration, and after1, after2, after3, and after4 for the 1, 2, 3, and 4 years following migration, respectively.

A test of the equivalence of male and female coefficients jointly across all post-migration periods fails to reject a null hypothesis of no difference (p = 0.155); this in part reflects increasing standard errors on estimates as the number of post-migration years increases, in turn reflecting the smaller number of observations for subsequent periods.

Because wages and household wages are zero for many observations, we added 1 to these variables before taking their log. Log household wages is coded as zero for singles (but individual wages are included for all individuals).

To keep the description concise, we discuss the main findings here rather than presenting them in figures or tables; results are available from the corresponding author.

This is shown by the (significant) positive coefficient on before2.

References

Bielby, W. T., & Bielby, D. D. (1992). I will follow him: Family ties, gender-role beliefs, and reluctance to relocate for a better job. American Journal of Sociology, 97(5), 1241–1267.

Boyle, P., Cooke, T., Halfacree, K., & Smith, D. (1999). Gender inequality in employment status following family migration in GB and the US: The effect of relative occupational status. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 19(9/10/11), 109–143.

Brickman, P., & Campbell, D. T. (1971). Hedonic relativism and planning the good society. In M. H. Appley (Ed.), Adaptation-level theory: A symposium (pp. 287–305). New York: Academic Press.

Chen, Y., & Rosenthal, S. S. (2008). Local amenities and life-cycle migration: Do people move for jobs or fun? Journal of Urban Economics, 64(3), 519–537.

Clark, A. E., Diener, E., Georgellis, Y., & Lucas, R. E. (2008). Lags and leads in life satisfaction: A test of the baseline hypothesis. The Economic Journal, 118(529), F222–F243.

Clark, W. A., & Withers, S. D. (2002). Disentangling the interaction of migration, mobility, and labor-force participation. Environment and Planning A, 34(5), 923–945.

Cooke, T. J. (2001). ‘Trailing wife’ or ‘trailing mother’? The effect of parental status on the relationship between family migration and the labor-market participation of married women. Environment and Planning A, 33(3), 419–430.

Cooke, T. J. (2003). Family migration and the relative earnings of husbands and wives. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 93(2), 338–349.

Cooke, T. J. (2008a). Gender role beliefs and family migration. Population Space and Place, 14(3), 163.

Cooke, T. J. (2008b). Migration in a family way. Population, Space and Place, 14(4), 255–265.

DaVanzo, J. (1976). Why families move: A model of the geographic mobility of married couples. http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED135697. Accessed 26 Jan 2019.

De Jong, G. F., & Graefe, D. R. (2008). Family life course transitions and the economic consequences of internal migration. Population, Space and Place, 14(4), 267–282.

Dolan, P., Peasgood, T., & White, M. (2008). Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29(1), 94–122.

Duncan, R. Paul, & Perrucci, C. C. (1976). Dual occupation families and migration. American Sociological Review, 41(2), 252–261.

Frijters, P., Johnston, D. W., & Shields, M. A. (2008). Happiness dynamics with quarterly life event data. IZA discussion paper 3604.

Glaeser, E. L., & Gottlieb, J. D. (2009). The wealth of cities: Agglomeration economies and spatial equilibrium in the united states. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(4), 983–1028.

Grimes, A., Ormsby, J., & Preston, K. (2017). Wages, wellbeing and location: Slaving away in Sydney or cruising on the gold coast. Motu working paper 17-07. Wellington: Motu Economic & Public Policy Research.

Jacobsen, J. P., & Levin, L. M. (2000). The effects of internal migration on the relative economic status of women and men. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 29(3), 291–304.

Jr, B., Robert, O., Wolfe, D. M., Oppong, C., Seroussi, M., Lillard, L. A., et al. (1995). Husbands and wives: The dynamics of married living. American Journal of Sociology, 100(5), 165–178.

Kettlewell, N. (2010). The impact of rural to urban migration on wellbeing in Australia. Australasian Journal of Regional Studies, 16(3), 187.

Lichter, D. T. (1980). Household migration and the labor market position of married women. Social Science Research, 9(1), 83–97.

Lichter, D. T. (1983). Socioeconomic returns to migration among married women. Social Forces, 62(2), 487–503.

Long, L. H. (1974). Women’s labor force participation and the residential mobility of families. Social Forces, 52(3), 342–348.

Lundberg, S., & Pollak, R. A. (1996). Bargaining and distribution in marriage. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10(4(Fall)), 139–158.

Lundberg, S., & Pollak, R. A. (2003). Efficiency in marriage. Review of Economics of the Household, 1(3), 153–167.

Lundberg, S. J., Pollak, R. A., & Wales, T. J. (1997). Do husbands and wives pool their resources? Evidence from the United Kingdom child benefit. Journal of Human Resources, 32(3), 463–480.

Maxwell, N. L. (1988). Economic returns to migration: Marital status and gender differences. Social Science Quarterly, 69(1), 108.

Melzer, S. M. (2011). Does migration make you happy? The influence of migration on subjective well-being. Journal of Social Research & Policy, 2(2), 73.

Mincer, J. (1977). Family migration decisions. NBER Working Paper No. 199. Mass, USA: National Bureau of Economic Research Cambridge.

Morrison, D. R., & Lichter, D. T. (1988). Family migration and female employment: The problem of underemployment among migrant married women. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 50(1), 161–172.

Nowok, B., Van Ham, M., Findlay, A. M., & Gayle, V. (2013). Does migration make you happy? A longitudinal study of internal migration and subjective well-being. Environment and Planning A, 45(4), 986–1002.

Roback, J. (1982). Wages, rents, and the quality of life. Journal of Political Economy, 90(6), 1257–1278.

Sandell, S. H. (1977). Women and the economics of family migration. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 59(4), 406–414.

Shihadeh, E. S. (1991). The prevalence of husband-centered migration: Employment consequences for married mothers. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53(2), 432–444.

Acknowledgements

This paper uses unit record data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. The HILDA Project was initiated and is funded by the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS) and is managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (Melbourne Institute). The findings and views reported in this paper, however, are those of the authors and should not be attributed to either DSS or the Melbourne Institute. We thank Judd Ormsby for his insights and thank two referees of this journal for helpful comments on an earlier draft.

Funding

This research was funded through Marsden Fund Grant MEP1201 from the Royal Society of New Zealand.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Preston, K., Grimes, A. Migration, Gender, Wages and Wellbeing: Who Gains and in Which Ways?. Soc Indic Res 144, 1415–1452 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02079-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02079-y