Abstract

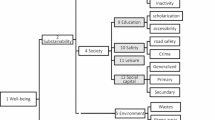

This paper provides a composite indicator of well-being for the 35 OECD countries, as well as South Africa, Russia and Brazil for the period 2013–2016, considering data on 10 different well-being domains from the OECD Better Life Index. In a first stage, countries are ranked according to their well-being indicator, constructed combining Data Envelopment Analysis with the Benefit-of-the-Doubt principle and Multi-Criteria-Decision-Making techniques. In a second stage, well-being clubs are identified using hierarchical cluster analysis, revealing that well-being is highly polarised. Moreover, as well-being affects people, population size is accounted for in the cluster analysis, showing that for the largest proportion of people in our sample, well-being is remarkably low.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Available at www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org.

The debates on whether or not to weight, and how to weight are not free from controversy. However, we agree with Hsieh (2004) that, despite its shortcomings, weighting is a useful practice that merits consideration in empirical analyses of well-being.

In this respect, the BLI webpage allows users to weight the different domains in order to create their own overall well-being indicator according to their individual preferences. While this is an interesting option for users, we do not believe it is particularly useful for scientific analyses. Furthermore, users’ weights might differ from those of the people interviewed in the BLI dataset.

In addition to all OECD countries, we decided to also include Brazil, Russia and South Africa in our analysis because they account for an important share of the total world population, particularly the first two. Furthermore, it is well known that the discriminating capacity of the DEA-BoD techniques employed in our empirical strategy increases with the number of observations. Accordingly, including the three above-mentioned countries improves the suitability of this technique for the purpose of our research.

Furthermore, Mizobuchi (2017b) also employed the BLI dataset to decompose cross-country differences in subjective well-being as the result of both socio-economic factors and sensitivity of happiness. However, we do not believe that paper represents a precedent for our research since its main purpose is not to compute a well-being composite indicator.

Existing literature in the field of well-being assessment at the macro level, e.g., using data on countries or other geographical areas, has tended to disregard the idea that well-being actually affects people’s daily life. However, in our view, it is important to take into account the number of people that experience low/high well-being, since it can yield a more realistic picture of how life is in the world than mere indicators can. For example, well-being in highly developed economies such as Switzerland or the European Nordic countries is probably high, but in terms of relative population they represent only a small fraction; on the contrary, developing countries such as Brazil and Russia are highly populated, but we might expect them to have relatively low levels of well-being.

These data are publicly available at www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org. At the time of writing this paper, the last update was made in June 2016.

This database is similar in nature to the BLI, although the information provided differs in terms of indicators and time coverage.

For the homicide rate indicator, the 10th and 90th percentiles are considered to capture its variability.

It is worth pointing out that Latvia joined the OECD in 2016, the year in which the non-OECD country South Africa was first included in the BLI dataset. Accordingly, data for these two countries refer to 2016.

In recent decades, DEA has been used in hundreds of empirical papers to assess different facets of performance (see Cook and Seiford 2009; Sueyoshi et al. 2017 for reviews), or even to build composite indicators. The flexibility of this technique in assessing performance in different frameworks constitutes one of its main advantages. However, as with other techniques in the field of social sciences, DEA also has its limitations. In addition to those specifically mentioned later in this paper regarding the construction of composite indicators to establish rankings, general limitations of DEA include its deterministic nature and the sensitivity of the results to the presence of outliers and/or influential observations in the sample. The latter drawback requires careful treatment of the dataset before computing the performance indicators; e.g., identifying and deleting outliers. Further details on DEA are provided in Cooper et al. (2007).

In more technical terms, in order to translate the conventional input/output DEA formulation into an appropriate model for computing a composite well-being indicator, it must be assumed that each country has what Lovell et al. (1995: 509), following Koopmans (1951), called a helmsman. According to the former authors, ‘… this assumption implies that one input, the helmsman, provides varying amounts of several services [well-being domains in our case study], and that every country has exactly one helmsman. Thus the input vector collapses to a scalar, and the value of this scalar is unity for every country’.

This approach thus avoids the use of exogenous weighting schemes based on expert opinions or other ad hoc criteria; e.g. the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP).

In practice, this can be done by computing a series of composite well-being indicators with enough values for the parameter t (always ranging from zero to one), e.g., at intervals of 0.001, as we do in this paper, and then calculating the average as the sole well-being indicator.

In contrast, non-hierarchical approaches are less popular for implementation reasons. They require the establishment of a central point or seed, from which distance to the observations is measured. In most cases, however, the identification of this central point is complicated.

As shown by the Spearman’s rank correlations displayed in Table 3, and as already commented on, the well-being scores obtained in the collective optimum and the most penalised country optimum scenarios lead to very similar rankings of countries as with the integer solution. Results at the country level from the collective optimum and the most penalised country optimum scenarios are available upon request.

In Mizobuchi (2014), the number of countries with well-being scores of one ranges between 6 and 18 (out of 34), depending on the model considered, pointing to a worrying lack of discriminating capacity of the DEA-BoD models employed. Additionally, countries such as Turkey and Brazil are awarded well-being scores equal to one in most of the scenarios considered, which seems quite implausible.

These two additional correlations reach values of 0.460 and 0.581, respectively; moreover, both are also statistically significant at the 1% confidence level.

Kernel distributions and clustering analyses have also been carried out using the DEA-BoD-MCDM scores obtained in the collective optimum and most penalised country optimum scenarios, yielding no significant differences with respect to those presented in the DEA-BoD-MCDM-integer scenario. The results for these alternative analyses are available upon request.

References

Adler, N., & Golany, B. (2002). Including principal components weights to improve discrimination in data envelopment analysis. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 53, 985–991.

Andersen, P., & Petersen, N. (1993). A procedure for ranking efficient units in data envelopment analysis. Management Science, 39, 1261–1264.

Barrington-Leigh, C., & Escande, A. (2016). Measuring progress and well-being: A comparative review of indicators. Social Indicators Research. doi:10.1007/s11205-016-1505-0.

Bernini, C., Guizzardi, A., & Angelini, G. (2013). DEA-like model and common weights approach for the construction of a subjective community well-being indicator. Social Indicators Research, 114(2), 405–424.

Charnes, A., Cooper, W. W., & Rhodes, E. (1978). Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. European Journal of Operational Research, 2(6), 429–444.

Chen, Y., Larbani, M., & Chang, Y. (2009). Multiobjective data envelopment analysis. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 60, 1556–1566.

Cherchye, L., Moesen, W., Rogge, N., & Van Puyenbroeck, T. (2007). An introduction to ‘benefit of the doubt’ composite indicators. Social Indicators Research, 82(1), 111–145.

Conover, W. J. (1999). Practical nonparametric statistics (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Cook, W. D., & Seiford, L. M. (2009). Data envelopment analysis (DEA)—thirty years on. European Journal of Operations Research, 192, 1–17.

Cooper, W. W., Seiford, L. M., & Tone, K. (2007). Data envelopment analysis. A comprehensive text with models, applications, references and DEA-Solver software. New York: Springer.

Despotis, D. K. (2002). Improving the discriminating power of DEA: Focus on globally efficient units. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 53, 314–323.

Despotis, D. K. (2005a). A reassessment of the human development index via data envelopment analysis. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 56(8), 969–980.

Despotis, D. K. (2005b). Measuring human development via data envelopment analysis: the case of Asia and the Pacific. Omega, 33(5), 385–390.

Dolan, P., & Metcalfe, R. (2012). Measuring subjective wellbeing: Recommendations on measures for use by national government. Journal of Social Policy, 41, 409–427.

Domínguez-Serrano, M., & Blancas, F. J. (2011). A gender wellbeing composite indicator: The best–worst global evaluation approach. Social Indicators Research, 102, 477–496.

Durand, M. (2015). The OECD better life initiative: How’s life? and the measurement of well-being. Review of Income and Wealth, 61(1), 4–17.

Dyson, R., Allen, R., Camanho, A., Podinovski, V., Sarrico, C., & Shale, E. (2001). Pitfalls and protocols in DEA. European Journal of Operational Research, 132, 245–259.

Everett, G. (2015). Measuring national well-being: A UK perspective. Review of Income and Wealth, 61(1), 34–42.

Everitt, B. S., Landau, S., Leese, M., & Stahl, D. (2011). Cluster analysis (5th ed.). Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Farrell, M. (1957). The measurement of productive efficiency. The Journal of Royal Statistical Society Series A, 120, 253–281.

Fleurbaey, M. (2015). Beyond income and wealth. Review of Income and Wealth, 61(2), 199–219.

Fox, J. (1990). Describing univariate distributions. In J. Fox & J. S. Long (Eds.), Modern methods of data analysis (pp. 58–125). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Golany, B. (1988). An interactive MOLP procedure for the extension of DEA to effectiveness analysis. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 39, 725–734.

Guardiola, J., & Picazo-Tadeo, A. J. (2014). Building weighted-domain composite indices of life satisfaction with data envelopment analysis. Social Indicators Research, 117, 257–274.

Hashimoto, A., & Kodama, M. (1997). Has livability of Japan gotten better for 1956–1990? A DEA approach. Social Indicators Research, 40, 359–373.

Henderson, D. J., & Parmeter, C. F. (2015). Applied nonparametric econometrics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hsieh, C. (2004). To weight or not to weight: The role of domain importance in quality of life measurement. Social Indicators Research, 68, 163–174.

Jahansahahloo, G. R., Memariani, A., Hosseinzadeh, F., & Rezai, H. Z. (2005). A note on some of DEA models and finding efficiency and complete ranking using common set of weights. Applied Mathematics and Computation, 166, 265–281.

Jones, M., Chris, J. S., & Sheather, J. S. (1996). A brief survey of bandwidth selection for density estimation. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 91, 401–407.

Jurado, A., & Pérez-Mayo, J. (2012). Construction and evolution of a multidimensional well-being index for the Spanish regions. Social Indicators Research, 107, 259–279.

Kao, C., & Hung, H. T. (2005). Data envelopment analysis with common weights: The compromise solution approach. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 56, 1196–1203.

Koopmans, T. C. (1951). An analysis of production as an efficient combination of activities. In T. C. Koopmans (Ed.), Activity analysis of production and allocation. Cowles Commission for Research in Economics, Monograph 13. New York: Wiley

Li, X., & Reeves, G. R. (1999). A multiple criteria approach to data envelopment analysis. European Journal of Operational Research, 115, 507–517.

Lorenz, J., Brauer, C., & Lorenz, D. (2016). Rank-optimal weighting or ‘‘How to be best in the OECD Better Life Index?’’. Social Indicators Research. doi:10.1007/s11205-016-1416-0.

Lovell, C. A. K., Pastor, J. T., & Turner, J. A. (1995). Measuring macroeconomic performance in the OECD: A comparison of European and non-European countries. European Journal of Operations Research, 87, 507–518.

Mahlberg, B. & Obersteiner, M. (2001). Remeasuring the HDI by Data Envelopment Analysis. Interim Report 01–069. Laxenburg, Austria: International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Mariano, E. B., Sobreiro, V. A., & Rebelatto, D. A. N. (2015). Human development and data envelopment analysis: A structured literature review. Omega, 54, 33–49.

Mizobuchi, H. (2014). Measuring world better life frontier: a composite indicator for OECD better life index. Social Indicators Research, 118, 987–1007.

Mizobuchi, H. (2017a). Incorporating sustainability concerns in the Better Life Index: Application of corrected convex non-parametric least squares method. Social Indicators Research, 131(3), 947–971.

Mizobuchi, H. (2017b). Measuring socio-economic factors and sensitivity of happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18, 463–504.

Murias, P., Martínez, F., & de Miguel, C. (2006). An economic wellbeing index for the Spanish Provinces: A data envelopment analysis approach. Social Indicators Research, 77, 395–417.

OECD, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2008). Handbook on constructing composite indicators: Methodology and user guide. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Osberg, L., & Sharpe, A. (2002). An index of economic well–being for selected OECD countries. Review of Income and Wealth, 48(3), 291–316.

Osberg, L., & Sharpe, A. (2005). How should we measure the ‘economic’ aspects of well-being? Review of Income and Wealth, 51(2), 311–336.

Reig-Martínez, E. (2013). Social and economic wellbeing in Europe and the Mediterranean Basin: Building an enlarged human development indicator. Social Indicators Research, 111, 527–547.

Reig-Martínez, E., Gómez-Limón, J. A., & Picazo-Tadeo, A. J. (2011). Ranking farms with a composite indicator of sustainability. Agricultural Economics, 42, 561–575.

Rojas, M. (2007). The complexity of well-being: A life-satisfaction conception and a domains-of-life approach. In I. Gough & A. McGregor (Eds.), Researching well-being in developing countries: From theory to research (pp. 259–280). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rojas, M. (2008). Experienced poverty and income poverty in Mexico: A subjective well-being approach. World Development, 36(6), 1078–1093.

Rojas, M. (2011). The measurement of economic performance and social progress’ report and quality of life: Moving forward. Social Indicators Research, 102, 169–180.

Rojas, M., & García-Vega, J. J. (2017). Well-being in Latin America. In R. J. Estes & M. J. Sirgy (Eds.), The pursuit of human well-being. The untold global history (pp. 217–255)., International handbooks of Quality-of-Life New York: Springer.

Sheather, S. J., & Jones, M. C. (1991). A Reliable data-based bandwidth selection method for Kernel density estimation. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 53(3), 683–690.

Sinuany-Stern, Z., & Friedman, L. (1998). DEA and the discriminant analysis of ratios for ranking units. European Journal of Operational Research, 111, 470–478.

Stiglitz, J.E., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J.P. (2009). Technical report, Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress.

Sueyoshi, T., Yuan, Y., & Goto, M. (2017). A literature study for DEA applied to energy and environment. Energy Economics, 62, 104–124.

Tone, K. (2001). A slacks-based measure of efficiency in data envelopment analysis. European Journal of Operational Research, 130, 498–509.

Torgersen, A., Førsund, F., & Kittelsen, S. (1996). Slack adjusted efficiency measures and ranking of efficient units. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 7, 379–398.

Ven, P. (2015). Introduction to the symposium on new measures of well-being: Perspectives from statistical offices. Review of Income and Wealth, 61(1), 1–3.

Zaim, O., Färe, R., & Grosskopf, S. (2001). An economic approach to achievement and improvement indexes. Social Indicators Research, 56, 91–118.

Zhou, P., Ang, B. W., & Poh, K. L. (2007). A mathematical programming approach to constructing composite indicators. Ecological Economics, 62, 291–297.

Zhu, J. (2001). Multidimensional quality-of-life measure with an application to Fortune’s best cities. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 35, 263–284.

Zohrehbandian, M., Makui, A., & Alinezhad, A. (2009). A compromise solution approach for finding common weights in DEA: An improvement to Kao and Hung’s approach. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 61, 604–610.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness and the European Regional Development Fund (ECO2014-55221-P and ECO2016-75237-R), as well as from the Valencian government (PROMETEOII/2014/053). Moreover, we are thankful for useful comments and suggestions received from the referees.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Peiró-Palomino, J., Picazo-Tadeo, A.J. OECD: One or Many? Ranking Countries with a Composite Well-Being Indicator. Soc Indic Res 139, 847–869 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1747-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1747-5

Keywords

- Composite indicators

- Data Envelopment Analysis

- Hierarchical cluster analysis

- Multi-Criteria-Decision-Making

- OECD Better Life Index

- Well-being