Abstract

To what extent do men objectify and dehumanize Black and White women based on shifting standards of sexuality? Across five experimental studies (2 pre-registered; N = 702), White (Studies 1-4a) and Black (Study 4b) American heterosexual men evaluated a series of images of Black and White women who were either fully- or scantily-clothed, and provided ratings of sexual objectification, animalistic dehumanization, and perceived appropriateness of the image for use in advertising. Participants responded to images of fully-clothed Black women with greater sexual objectification and animalistic dehumanization, and lower appropriateness, compared to fully-clothed White women. However, scantily-clothed White women elicited greater sexual objectification and animalistic dehumanization, and lower attributions of appropriateness compared to scantily-clothed Black women. These race interactions with clothing type support a default objectification hypothesis for Black women, and a shifting standards of sexuality hypothesis for White women. An internal meta-analysis across the five experiments further supported these two hypotheses. This research illuminates the importance of examining racialized sexual objectification in terms of distinct group-specific perceptions and attributions. Implications of this intersectional account of objectification for intergroup relations are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

To what extent do men differentially objectify and dehumanize Black and White women in neutral and sexualized contexts? We suggest that evaluations of women from different racial groups are made with reference to group-specific expectations or standards (Biernat et al., 1991; Biernat & Manis, 1994). As a result, an appraisal of a scantily-clothed woman as “very sexual” may mean something different when she is White versus Black, because each woman is being compared to sexuality standards for her race. Racialized sexual stereotypes attribute heightened sexuality and animalism to Black compared to White women; in this sense, standards or expectations of sexuality are higher for Black than White women. In this research, we investigate White and Black heterosexual men’s objectification and dehumanization of modestly versus scantily-clothed Black and White women.

Specifically, we consider and extend intersectional feminist theorizing on race and sexuality and the shifting standards model to predict that women’s race (Black or White) and clothing (full or scant) will interact to produce two distinct but complementary patterns. The default objectification hypothesis posits that, due to social representations of Black women as hypersexual and animalistic, men will exhibit an assimilative judgment pattern, objectifying and animalistically dehumanizing fully-clothed Black women to a greater extent than fully-clothed White women. The shifting standards of sexuality hypothesis posits that normative expectations of sexual respectability imposed on White women lead men to objectify scantily-clothed White women—who violate these expectations—to a greater extent than scantily-clothed Black women.

What is Sexual Objectification and Animalistic Dehumanization?

Sexual objectification refers to the tendency to perceive or behave toward a person in a manner that likens them to a sexual object or commodity, independent of their personal characteristics, subjectivity, or conceptions of humanity (Bartky, 1990; Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997; Goffman, 1979; Leyens et al., 2000). Objectification theory provides a conceptual framework explaining how sexual objectification centers a woman’s physical appearance and has a host of negative consequences for women and the broader society (Fredrickson & Roberts;, 1997). More broadly, feminist philosopher Nussbaum (1995, 1999) conceptualizes objectification as an umbrella term for a variety of manifestations of treating a human as an object. These include instrumentality, denial of autonomy, inertness, fungibility, violability, ownership, and denial of subjectivity. Some forms of objectification cover many of these components (e.g., enslavement), and others only one (e.g., parental denial of autonomy to a small child). The morality of objectification is dependent on the broader social and historical context and the nature of the relationship between perceiver and target.

Empirical research on sexual objectification has also taken a number of forms. One is a global process of literal objectification (Goldenberg, 2013; Heflick & Goldenberg, 2014) that occurs when a perceiver focuses (solely or primarily) on a target’s physical features. Other aspects of objectification have been assessed through object-like trait attributions to targets (e.g., Gray et al., 2007; Haslam, 2006; Heflick & Goldenberg, 2009), visual and neural markers (Gervais et al., 2012; Cikara et al., 2011), and objectifying behaviors (e.g. Saguy et al., 2010; Fredrickson and Harrison, 2005; Fredrickson et al., 1998). These diverse methodologies reflect the multidimensional nature of the broader construct of objectification (Nussbaum, 1995, 1999).

Sexual objectification can also contribute to appraisal of others as less than fully human (Loughnan & Pacilli, 2014; Vaes et al., 2011, 2014), thus depriving them of mind and agency (Cikara et al., 2011; Gray et al., 2011). A large literature on dehumanization points to its links to aggression (see Bandura, 1990; Bar-Tal, 1990; Kelman, 1976; Opotow, 1990). Haslam (2006) outlines two dimensions of dehumanization: Mechanistic dehumanization, which involves perceiving a target as inert, fungible, cold, and lacking in agency, like a robot or a machine (Haslam, 2006; Loughnan et al., 2009), and animalistic dehumanization, in which targets are represented as animal-like, instinctual, and unrefined (Bastian & Haslam, 2011; Haslam, 2006; Haslam & Loughnan, 2014; Haslam & Stratemeyer, 2016). When animalistically dehumanized, people are seen as amoral, childlike, and unable to control themselves (Gervais et al., 2013).

Sexual objectification and dehumanization are clearly related, and in the present research, we measure animalistic dehumanization of female targets along with judgments related to general objectification and sexuality (Budesheim, 2011; Gervais et al., 2013). Sexualized portrayals of women should increase the extent to which they are both objectified and dehumanized as animal-like. Morris et al. (2018) found that a sexual objectification focus (e.g., by portraying the target as a pornographic film actress in scantily-clad clothing) facilitated greater animalistic dehumanization compared to an appearance-focused objectification (e.g., by portraying the target as a fashion model with no exposed skin). Sexually objectified women are also viewed as more animal-like compared to women who are not sexually objectified (e.g., Bongiorno et al., 2013; Puvia and Vaes, 2013; Vaes et al., 2011).

Dehumanization has often been considered in the context of intergroup relations (e.g., Haslam, 2006; Leyens et al., 2003), such as the pervasive racist representation of Black people as apes (Goff et al., 2008; Lott, 1999), Black men as bucks (Curry, 2017), and Black women as mules (Stewart, 2017; Porcher & Austin, 2021). Dehumanization is a distinct form of prejudice that predicts the most insidious intergroup outcomes (Kteily & Bruneau, 2017; Wilde et al., 2014). Those who associate Black people with apes are more likely to justify violence against them (Goff et al., 2008; Lott, 1999). Men who implicitly associate women with animals report greater intentions to engage in sexual harassment and rape (Rudman & Mescher, 2012). Animalistic imagery is associated with acceptance of genocide and other forms of intergroup violence (Kahn et al., 2015; Kelman, 1976) in that it allows perceivers to avoid moral consideration of the dehumanized group altogether (Kelman, 1976; Opotow, 1990).

Animalistic dehumanization is particularly relevant to people’s judgments of the bodies of Black women (Bastian & Haslam, 2011; Haslam, 2006; Haslam & Loughnan, 2014; Haslam & Stratemeyer, 2016). Portrayals of Black women as animalistically sexual are dominant in societal and cultural discourse, particularly in media representations (Mitchell et al., 2023). The fashion industry portrays Black fashion models in animal print more frequently compared to White fashion models (Plous & Neptune, 1997), and music videos, movies and television shows often depict Black women as sexually aggressive (Ramsey & Horan, 2018; Stephens & Phillips, 2005; Ward et al., 2012; West, 2008). These social representations reinforce stereotypes of Black women as essentially sexual, primal, and animalistic, and may contribute to different patterns of objectification and dehumanization for Black and White women.

Sexual Stereotypes of White and Black Women

Due to the prototypicality of whiteness in the superordinate representation of women (e.g., see Ghavami and Peplau, 2013), there is scant explicit reference to sexual archetypes of White women (Frankenberg, 1993; Hegarty, 2017). But women (presumably White) have long been sexually dichotomized as Madonnas or Whores (Bay-Cheng, 2015a). This binary supposes that women are suited to being either wives/mothers (associated with positive traits) or are sexually “out of control” (associated with negative traits; Bay-Cheng, 2015a, 2015b; Tanzer, 1985). Women who pose a threat to the gender hierarchy (e.g., by being “overly” sexual) are often victims of misogyny and derogation, while women who behave in line with restricted gender roles (e.g., by adhering to standards of feminine purity) are often rewarded (Glick & Fiske, 1996). This system maintains the gender status quo by justifying hostility towards “bad women” and extending protection to “good women” (Connor et al., 2017). As a result, women are pressured to follow rigid scripts of sexuality, and to grant men power as sexual instigators who may punish out of control women through sexual objectification (Bareket et al., 2018; Frith, 2009; Frith & Kitzinger, 2001). Sexual objectification is part of a larger system of social control that maintains gender inequality (Calogero, 2013).

But stereotypes of women differ by race. Ghavami and Peplau (2013) examined intersectional stereotypes by asking U.S. college students to generate attributes of groups that varied by gender and/or race or reflected single categories (e.g., Black women, Black people, Women, Black men, White people). Prominent traits generated to describe White women included submissive, attractive, and feminine (also mentioned in general stereotypes of women), and unique to this intersectional category, sexually liberal. This suggests that White women may be generally stereotyped as sexually respectable and desirable, but nonetheless (some of them) inclined to some sexual impropriety. In contrast, promiscuous and aggressive were unique stereotype attributed to Black women that were not present in stereotypes of women or Black people (Ghavami & Peplau, 2013). Attributes generated for Black women also revealed a preoccupation with Black women’s bodies, including such terms as big butt, overweight, dark-skinned and hair weaves (Ghavami & Peplau, 2013), as well as not feminine. Such features position Black women directly in contrast to the Eurocentric norms of womanhood (Patton, 2006; Thomas et al., 2014).

Other research highlights multiple archetypes of Black women, the most notable of which is the Jezebel archetype, which portrays Black women as immoral, promiscuous, sexually available, and animalistic (Collins, 2000; Davis, 1981; Donovan, 2011; hooks, 1984; Turner, 2011; West, 2008; Woodard and Mastin, 2005). Historically, such stereotypes were used as a justification for sexual exploitation of enslaved Black women (Hammonds, 2004, 2017; Jewell, 1993), and served to dehumanize Black women, making it culturally and legally acceptable to engage in sexual violence against them (State of Missouri v. Celia, A Slave, 1855). These stereotypes of Black women persisted into the Jim Crow era and endure today, as reflected in objectifying media images of Black women’s bodies (Conrad et al., 2006; Ward et al., 2012).

Sexual Objectification of Black Versus White Women

Intersectionality theory argues that the experiences and perceptions of Black women cannot be reduced to simple addition of the effects of their component identities, but rather emerge in complex ways, rooted in historical and continuing systems of oppression (Cole, 2009; Collins, 2000; Crenshaw, 1991, 1993; Purdie-Vaughns & Eibach, 2008). Early research on objectification focused primarily on the perceptions and experiences of White college women (see Moradi and Huang, 2008), but more recent research has shed light on how the intersection of Black women’s race and gender identities create unique experiences with sexualized stereotypes and objectification (Anderson et al., 2018; Bay-Cheng et al., 2020; Biefeld et al., 2021; Brown Givens & Monahan, 2005; Daniels et al., 2022; Leath et al., 2021; Rosenthal & Lobel, 2016; Townsend et al., 2010; Watson et al., 2012). In Table 1, we briefly summarize this body of research, referencing some in more detail below.

The Jezebel stereotype and animalistic depictions of Black women suggest that Black women are more likely to be objectified and dehumanized than White women. Some research directly supports this pattern (see Table 1), but other findings point to contextual and methodological variation. For example, Bay-Cheng and colleagues (2020) assessed Black and White women and men’s perceptions of sexually active Black (e.g., Tanisha) versus White (e.g., Claire) female targets. Target race did not affect quantitative judgments of competence and warmth, but qualitative comments about Black and White women differed: For the Black woman target, 44% of comments were categorized as unfavorable, whereas for the White woman, only 17% of the comments were unfavorable. The tone of these negative comments also differed by race, with the Black woman characterized as easy, dirty, good to use, a hoe, a whore, likes attention and, trashy, and the White woman as young, immature, puts a lot of energy on gratification, and needs to be more careful. References to racialized gender slurs (Lewis et al, 2016) and metaphors of contamination (Haidt, 2001; White & Landau, 2016) were fairly common for the Black woman, but comments about the White woman suggested leniency and standards of purity. “Black girls and women are held to a different sexual standard than their White counterparts” (Bay-Cheng et al., 2020, p. 304).

Using eye-tracking technology to assess visual attention to women’s body parts (i.e., time spent fixating on the chest and hip/waist divided by the average fixation on the whole body plus face), Anderson and colleagues (2018) found that White participants’ visual attention to body parts was greater for Black than White targets, and attention to faces was greater for White than Black targets, especially when these women were presented in a sexualized manner (e.g., wearing bikinis). Participants in this study were predominantly women; given that women are less likely than men to objectify other women (Strelan & Hargreaves, 2005), different findings might emerge in a sample of men. In a follow-up study that did include more men, participants associated both Black and White women with animals and objects on an implicit categorization task, regardless of whether they were presented in sexualized or non-sexualized clothing. These effects were slightly larger for Black women than White women, an intergroup dehumanization effect consistent with previous empirical work (e.g., Goff et al., 2008). This research suggests that context can matter for how others are perceived, and clothing/dress can be an important contextual cue that can sexualize and thereby moderate objectification responses.

Target Clothing, Target Race, and Sexuality

Perceivers may interpret women’s clothing as sexually provocative, thereby signaling sexual interest, and/or as an attempt to emphasize (or deemphasize) sex appeal (Glick et al., 2005; Koukounas & Letch, 2001). Various factors lead some styles of clothing to be perceived as more provocative than others, but provocative attire is largely understood as “more skin = sexier” (Gurung & Chrouser, 2007, p. 93). Men are more likely to rate women who wear “provocative” clothing (e.g., a short black skirt and a cleavage-revealing shirt) as flirtatious, seductive, and promiscuous, compared to women who wear “neutral” clothing (e.g., denim jeans and a black turtleneck sweater; Koukounas and Letch, 2001).

Clothing style clearly matters for perceptions of women’s sexuality, but is provocative clothing viewed as equally sexual for women of diverse ethnicities? Daniels et al. (2022) presented Black and White college students with a mock social media profile and photo, through which target race (Black vs. White) and clothing style (scant vs. conservative dress) were manipulated. Scantily-clothed women were considered less moral, warm, and competent than those conservatively dressed, but clothing type affected sexual attractiveness judgments only in the case of White women. The authors suggest that “perhaps because of cultural narratives stigmatizing their sexuality, Black women may be consistently objectified regardless of their dress” (p. 224). For White women, “more formalized rules” may include a “standard that dictates a sexy self-presentation as more attractive” (p. 224).

Other evidence suggests that compared to Black women, White women may be more penalized for expressions of sexuality. Biefeld and colleagues (2021) found that White women perceivers rated Black women wearing sexualized clothing as more popular than non-sexualized Black women but rated sexualized White women as less popular and less nice than non-sexualized White women. Male perceivers rated all sexualized targets as more popular than those more conservatively dressed, regardless of target race. White women may be particularly harsh against other White (but not Black) women, perhaps due to social norms placed upon White women to be chaste and virtuous (Bay-Cheng, 2015a, 2015b; Tanzer, 1985). This research suggests there is more to learn about when perceivers sexualize and objectify Black versus White women, and the extent to which perceptions depend on contextual cues (e.g., clothing type).

Shifting Standards for Judging Women’s Sexuality

The shifting standards model (Biernat et al., 1991; Biernat & Manis, 1994) posits that judgments of others are influenced by relative comparisons. Group stereotypes serve as standards against which individual members of the group are judged, and therefore standards shift depending on the target’s category membership. For example, a woman’s leadership ability may be judged against (low) leadership expectations for women, whereas a man’s leadership ability may be judged against (high) leadership expectations for men (see Biernat, 2012; Gushue, 2004; Kobrynowicz and Biernat, 1997). This may produce contrast effects in subjective judgments, such that members of a group stereotyped as deficient on an attribute are judged as higher on that attribute, because they are evaluated relative to a lower standard.

We propose that stereotypes attributing hypersexuality to Black versus White women may implicate the use of different standards by which some people come to judge a Black versus White woman’s sexuality. When presented in a neutral context (fully-clothed, the default), Black women should be more sexually objectified and animalistically dehumanized than White women. However, a White woman who overtly conveys sexuality (e.g., through dress) may be considered more sexual than a comparable Black woman. That is, because overt expressions of sexuality may be more inconsistent with stereotypes of White than Black women, a judgmental contrast effect may occur, with scantily-clothed White women more sexually objectified and animalistically dehumanized than comparable Black women. The shifting standards model has not been applied to judgments of sexuality; the novelty of the present research is that it connects a social cognitive model (shifting standards) to the literature on objectification and dehumanization to predict differential sexual objectification of Black and White women, depending on context.

The Current Research

We report five studies focused on heterosexual men’s objectification of Black and White women, in which our key prediction is a statistical interaction between target race (White, Black) and target clothing (fully-clothed, scantily-clothed), with two specific hypotheses tested via simple effects tests:

Hypothesis 1

Based on stereotypes associating Black women with hypersexuality, the Black women default objectification hypothesis predicts that in neutral situations, when women are not overtly conveying sexuality (in our studies, through conservative clothing), men will sexually objectify and animalistically dehumanize Black women more than comparable White women.

Hypothesis 2

Due to the relatively weaker associations of White women with sexuality, the shifting standards of sexuality hypothesis suggests that in contexts where sexuality is conveyed (in our studies, through sexualized clothing), men will sexually objectify and animalistically dehumanize White women to a greater extent than Black women.

Note that we do not predict main effects of target race, and while we do predict main effects of clothing (more objectification of scantily-clothed than fully-clothed women), this is not a key focus of the research. Though main effects are reported, our central prediction is a race x clothing interaction on all dependent variables, and simple effects of race within each clothing type address the two hypotheses. In all five studies, we varied the race (Black/White) and clothing (fully-clothed/scantily-clothed) of women in fashion advertisements and asked White male (Studies 1-4a) and Black male (Study 4b) participants to evaluate these targets. Our main dependent variables were sexual objectification and animalistic dehumanization, but we also measured perceived “appropriateness for advertising use” to directly assess men’s normative expectations regarding how women “should” dress. Low appropriateness should correspond with higher sexual objectification and animalistic dehumanization; therefore we predict that fully-clothed Black women will be judged less appropriate for advertising than fully-clothed White women (H1), and scantily-clothed White women will be judged less appropriate for advertising than scantily-clothed Black women (H2).

In the first four studies (Study 1-4a), we intentionally focused only on White male participants because White men are over-represented in positions of societal power, including those that control representational media (magazines, television, etc.; see Chancellor, 2019). Status also enables White men to normalize the sexual objectification of women compared to Black men (Connell, 1987; Kimmel, 1987, 1994; see also the focus on objectification of Black people by White people in prior research; e.g., Goff et al., 2008; Jahoda, 1999). But we also broadened our framework by including a sample of Black men in Study 4b.

Previous studies that have included both Black and White perceivers have not found differences in the sexual objectification of Black and White targets (e.g., Bay-Cheng et al., 2020; Biefeld et al., 2021; Daniels et al., 2022). However, in one study comparing Black men and women, Black men more strongly endorsed the Jezebel stereotype, and this endorsement predicted greater justification of intimate violence towards Black women (Cheeseborough et al., 2020). Because race and gender stereotypes are culturally shared (Devine & Elliot, 1995; Schaller et al., 2002; Williams & Best, 1990), we did not anticipate differences in Black and White men’s perceptions. However, Black men may be particularly sensitive to the objectified portrayal of Black women, as it may confirm negative group stereotypes (Daniels et al., 2022; Steele and Aronson, 1995). In Study 4b, we focus on Black men’s objectification of Black and White women, thereby contributing to the diversification of psychological science, which too often relies on White samples (Henrich et al., 2010; Roberts et al., 2020).

Study 1

Study 1 assessed White men’s responses to Black and White women who are portrayed in a sexualized (scantily clothed) and a non-sexualized (fully clothed) context.

Method

Participants

The sample size for this study was determined a priori based on a power analysis in G*Power (Faul et al., 2009) that estimated medium effects (f = 0.25) and included other standard parameters (error = 0.05, 0.95 power) for a 2 × 2 mixed design. We had a goal of recruiting 50 participants for each of the two between-subjects conditions. A total of 99 White heterosexual male adults living in the United States were recruited via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (Mturk.com). We used a pre-screening survey to recruit White men, but three participants were excluded for later identifying as female during the demographics portion of the study. We excluded three additional participants for not completing the study, and three for checking a box at the end suggesting that they “did not complete the study in a distraction-free environment.” Of the 90 remaining participants, one did not provide ratings of Black targets and therefore was excluded, leaving a final sample of 89 participants for analysis. While this study could have had greater statistic power if we had oversampled for potential participant exclusion, a sensitivity power analysis in G*Power indicated that a sample of 89 participants was sufficient to detect a minimum effect size of f2 (1,87) = 0.258 or greater (α = 0.05, power = 0.80). These participants ranged in age from 22 to 66 years (M = 33.94, SD = 9.35). All materials and procedures described below and in subsequent studies were approved by the University of Kansas Institutional Review Board. In this and all subsequent studies, we report all measures, manipulations, and exclusions.

Design and Procedure

This study adopted a 2 (Target Race: Black, White) x 2 (Target Clothing: scantily-clothed, fully-clothed) mixed design, with target race as the within-subjects factor. Participants were asked to consider and evaluate eight images of Black and White women, all either scantily-clothed (i.e., presented in lingerie) or fully-clothed (i.e., presented in professional clothing).

Participants were told that the purpose of the study was to “examine how people view and rate different advertisements for an upcoming online clothing company. We want to know what people think about our clothes, our models, and the best way to market them.” They were told they would be viewing a series of photos for clothing advertisements. Each participant was exposed to 16 different images of women fashion models in total, including eight fully-clothed and scantily-clothed: three Black women, three White women, and one Asian woman, one Hispanic woman), presented in a randomized order. These images created the target race (White and Black) and target clothing (scantily-clothed vs. fully-clothed) manipulations. The scantily-clothed images presented photos of women in lingerie, and the fully-clothed images were photos of women in professional work attire. Images were taken from popular clothing websites for women in 2017 (e.g., Forever21, H&M), and were selected to be as similar as possible (body positioning, amount of skin presented, facial expression, hairstyle etc.) across race. A similar approach for creating stimuli were used by Anderson et al. (2018). The full set of materials is included in Supplement A in the online supplement. After all dependent measures, participants provided demographic information and were fully debriefed.

Dependent Measures

After viewing each image, participants completed the following dependent measures.

Perceived Appropriateness for Advertising

Appropriateness for advertising was assessed with three items: “How appropriate is it for this image to feature in advertising in the following contexts: Print media (magazines, newspapers, etc.), television (commercials, etc.), and social media (Facebook, Instagram, etc.).” Participants rated these items on a scale ranging from 1 (Very Inappropriate) to 7 (Very Appropriate). Reliabilities (αs) ranged from 0.81 − 0.95 for each target. For the analysis, we averaged across the three target women for each race: reliabilities for these overall indexes ranged from 0.90 to 0.97: (for scantily-clothed Black women α = 0.95; scantily-clothed White women α = 0.97; fully-clothed Black women α = 0.90; fully-clothed White women α = 0.91).

Sexual Objectification

Sexual objectification was assessed with a single face-valid item that has been used in prior experimental research assessing men’s objectification of women (Landau et al., 2012). Participants answered the item “When you see this advertisement, how much do you think about this model in terms of her…” item for each target on a scale ranging from 1 (Personality) to 7 (Body). A composite across the three women models of each race was created; αs ranged from 0.66 to 0.85 (scantily-clothed Black women α = 0.83; scantily-clothed White women α = 0.85; fully-clothed Black women α = 0.66; fully clothed White women α = 0.72).

Animalistic Dehumanization

Animalistic dehumanization was measured with a six-item scale adapted from Haslam (2006). Participants were asked to rate each woman on the following six dimensions: animalistic, wild, carnal, sensual, erotic, lustful from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree). We assessed reliability for each of the images, with αs ranging from 0.79 to 0.90. The composite based on responses to the three targets of each type was also reliable (αs from 0.73 to 0.87; scantily-clothed Black women α = 0.73; scantily-clothed White women α = 0.76; fully-clothed Black women α = 0.87; fully-clothed White women α = 0.85).

Exploratory Measures

We also assessed perceptions of target warmth, competence, femininity, and attractiveness, and to advance the cover story, we asked about the perceived cost of the clothing being advertised. At the end of the study, we measured need for power (Bennett, 1989) and ambivalent sexism (Glick & Fiske, 1996). See Supplement B for the materials and Supplement C for the mean scores in the online supplement.

Results

For each dependent variable, we computed a Target Race x Target Clothing mixed-model ANOVA, with Target Race as a within-subjects factor and Target Clothing as a between-subjects factor. We predicted a statistical interaction between Target Race and Target Clothing on perceived appropriateness, sexual objectification, and animalistic dehumanization, such that (a) among those exposed to fully-clothed targets, Black women would be sexually objectified, dehumanized and perceived as less appropriate than White women (Hypothesis 1), and (b) among those exposed to scantily-clothed targets, White women would be more sexually objectified, dehumanized, and perceived as less appropriate than Black women (Hypothesis 2). Means and standard deviations for all variables by condition appear in Table 2.

Advertising Appropriateness

The main effect of Target Race was not significant, F(1,87) = 0.965, p = .329, ηp2 = 0.011, but the main effect of Target Clothing, F(1,87) = 8.572, p = .004, ηp2 = 0.09, and the predicted Target Race x Target clothing interaction, F(1,87) = 11.470, p = .001, ηp2 = 0.116, were significant. A simple effects test supported Hypothesis 1: Among participants who viewed images of fully-clothed women, advertisements with Black women were seen as less appropriate than advertisements with White women, F(1,87) = 9.233, p = .003, ηp2 = 0.096. The reverse pattern was true among those who viewed images of scantily-clothed women, but this effect was not significant, F(1,87) = 2.992, p = .087, ηp2 = 0.033, therefore Hypothesis 2 was not supported. We also tested the simple effect of clothing type within each racial group: Scantily-clothed White targets were perceived as less appropriate than fully-clothed White targets, F(1,87) = 13.639, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.136, and the same, but weaker effect emerged for Black targets, F(1,87) = 4.129, p = .045, ηp2 = 0.045.

Sexual Objectification

The effect of Target Race was not significant, F(1,87) = 0.668, p = .416, ηp2 = 0.008, but the main effect of Target Clothing was significant, F(1,87) = 6.583, p = .012, ηp2 = 0.07, as was the predicted interaction, F(1,87) = 5.445, p = .022, ηp2 = 0.059. Confirming Hypothesis 1, when targets were fully-clothed, Black women were more objectified than White women, F(1,87) = 4.801, p = .031, ηp2 = 0.052. This Target Race effect was not significant when the targets were scantily-clothed, F(1,87) = 1.190, p = .278, ηp2 = 0.013, therefore Hypothesis 2 was not supported. Scantily-clothed White women were objectified more than fully-clothed White targets, F(1,87) = 10.618, p = .002, ηp2 = 0.109, but there was no effect of Target Clothing when targets were Black women, F(1,87) = 1.424, p = .236, ηp2 = 0.016.

Animalistic Dehumanization

The effects of Target Race, F(1,87) = 4.499, p = .037, ηp2 = 0.049, and Target Clothing, F(1,87) = 11.676, p = .001, ηp2 = 0.118, and their interaction, F(1,87) = 8.756, p = .004, ηp2 = 0.091, were all significant. When targets were fully-clothed, Black women more animalistically dehumanized than White women, F(1,87) = 12.483, p = .001, ηp2 = 0.125 (supporting H1), but contrary to H2, there was no race effect in the scantily-clothed condition, F(1,87) = 0.363, p = .548, ηp2 = 0.004. Scantily-clothed women were more animalistically dehumanized than fully-clothed women when they were White, F(1,87) = 17.013, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.164, and to a lesser extent, when they were Black, F(1,87) = 5.178, p = .025, ηp2 = 0.056.

Discussion

This initial study supported our predictions of differential objectification of Black and White female targets based on what they were wearing, as interactions between race and clothing were significant on all three dependent measures. Consistent with the Black women default objectification hypothesis (H1), we found that fully-clothed Black women were more likely to be sexually objectified, animalistically dehumanized and viewed as less appropriate than fully-clothed White women. When targets were scantily-clothed, this race difference was reversed, but was not significant for any of the dependent measures; the shifting standards hypothesis (H2) was not supported. Scantily-clothed White women were not sexually objectified or animalistically dehumanized more than scantily-clothed Black women and were not viewed as less appropriate.

As in Daniels et al. (2022), the effect of clothing was stronger for White women than Black women. Scant clothing resulted in more sexual objectification than full clothing, but only for White women; for animalistic dehumanization and appropriateness, the effects of clothing type emerged for both racial groups, but more strongly so for White women. This suggests a greater sensitivity among White men to contextual clothing cues in White than Black women.

One reason for the null effect of target race in judgments of scantily-clothed women may be that the stimuli used were not provocative enough to prompt perceived violation of White women stereotypes, and, in turn, increased objectification based on shifting standards (Gurung & Chrouser, 2007). Presenting women from the waist up may not have exposed enough skin to produce objectifying effects (Daniels et al., 2022). Therefore, in Study 2, we used full-body stimuli of both fully-clothed and scantily-clothed women. Study 1 may also have been underpowered; the Study 2 sample is slightly larger than the sample in Study 1.

Study 2

Study 2 was designed as a replication and extension of Study 1, using a stimuli set that depicted full bodies of Black and White, fully- and scantily-clothed women. As in Study 1, White male participants evaluated three Black women and three White women, depicted in either full or scant clothing, along with the filler images. We predicted a statistical interaction between target race and target clothing on appropriateness for advertising, objectification, and animalistic dehumanization, such that (a) fully-clothed Black women would be sexually objectified, dehumanized, and viewed as less appropriate than fully-clothed White women (H1), and (b) the reverse pattern would be observed for scantily-clothed targets (H2).

Method

Participants

A total of 104 White heterosexual men living in the United States were recruited via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (Mturk.com), using a prescreen targeting this population. The design and power analysis for this study was identical to Study 1. Two participants were excluded for later identifying as female, resulting in a final analytic sample of 102 participants. There were no other exclusions. A sensitivity power analysis in G*Power indicated that a sample of 102 participants would be sufficient to detect a minimum effect size of f2 (1,100) = 0.241 or greater (α = 0.05, power = 0.80). These participants ranged in age from 19 to 66 years (M = 33.89, SD = 10.83).

Design and Procedure

This study adopted the same 2 (Target Race: Black, White) x 2 (Target Clothing: scantily-clothed, fully-clothed) mixed design with target race as the within-subjects factor and clothing the between-subjects factor, as in Study 1. The same fully-clothed targets as in Study 1 were used (along with the filler Hispanic and Asian women photos), but we obtained a new set of scantily-clothed photos obtained in the same manner as in Study 1, in which the women’s full bodies were visible. This better equated the body-to-face ratio of this stimulus set with the fully-clothed images; see the online supplement for full materials. The procedures and manipulations were the same as in Study 1, with photos presented in a randomized order.

Dependent Measures

After viewing each image, participants responded to the same dependent measures as in Study 1: Appropriateness for advertising (αs ranged from 0.81 − 0.95 based on the three items for each target, and from 0.91 to 0.96 for the composites for each Target Race x Target Clothing group: scantily-clothed Black women α = 0.95; scantily-clothed White women α = 0.97; fully-clothed Black women α = 0.90; fully clothed White women α = 0.91), sexual objectification (αs ranged from 0.56 to 0.79: scantily-clothed Black women α = 0.79; scantily-clothed White women α = 0.73; fully-clothed Black women α = 0.71; fully-clothed White women α = 0.56), and animalistic dehumanization (αs based on the six items for each target ranged from 0.79 to 0.90, and for the composites, from 0.86 to 0.91: scantily-clothed Black women α = 0.91; scantily-clothed White women α = 0.96; fully-clothed Black women α = 0.87; fully-clothed White women α = 0.85).

In addition to the appropriateness questions from Study 1, participants were also asked about appropriateness for various billboard ads, including “in a popular shopping mall,” “in a bar or nightclub,” “on a busy street downtown,” “on a college campus,” “down the street from an elementary school,” and “at a city bus stop” on a scale from 1 (Very Inappropriate) to 7 (Very Appropriate). Results using this index were very similar to those using the 3-item index; to maintain consistency with Study 1, we report only the 3-item index.

As in Study 1, additional judgments of targets were collected, including clothing cost, perceived target competence, warmth, femininity, promiscuity, rationality, and attractiveness. Ambivalent sexism, need for power, intergroup prejudice, and self-esteem were measured at the end of the study. The means for these variables is included in Supplement C in the online supplement. Participants completed demographic questions before being debriefed.

Results

Each dependent measure was submitted to a 2 (Target Race: Black, White) x 2 (Target Clothing: scantily-clothed, fully-clothed) mixed design ANOVA, with target race as the within-subjects factor. Means by condition appear in Table 3.

Appropriateness for Advertising

The main effect of Target Race, F(1,100) = 3.32, p = .0712, ηp2 = 0.032, was not significant, but the main effect of Target Clothing, F(1,100) = 35.71, p < .001, ηp2 < 0.001, and the Target Race x Target Clothing interaction, F(1,100) = 13.39, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.118, were both significant. Disconfirming Hypothesis 1, among participants who were presented with images of fully-clothed women, advertisements with Black and White women were seen as equally appropriate, F(1,100) = 1.59, p = .21, ηp2 = 0.02. When targets were scantily-clothed, however, we found support for the shifting standards prediction (Hypothesis 2): Participants rated the images of White women as less appropriate than the images of Black women, F(1,100) = 15.97, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.14. Scantily-clothed were also judged as less appropriate than fully-clothed for White targets, F(1,100) = 43.70, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.304, and Black targets, F(1,100) = 25.29, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.202, but the effect of clothing was stronger for White targets.

Sexual Objectification

The effects of Target Race, F(1,100) = 7.304, p = .008, ηp2 = 0.068, Target Clothing, F(1,100) = 50.396, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.335, and their interaction, F(1,100) = 26.484, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.209, were all significant. Confirming Hypothesis 1, when the targets were fully-clothed, Black women were more objectified than White women, F(1,100) = 29.091, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.225. The reverse was true when targets were scantily-clothed, F(1,100) = 3.172, p = .078, ηp2 = 0.031, but this effect was not significant, therefore H2 was not supported on this variable. Scantily-clothed White targets were objectified more than fully-clothed White targets, F(1,100) = 81.647, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.449, with a weaker, but significant clothing effect for Black targets, F(1,100) = 17.426, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.148.

Animalistic Dehumanization

The effect of Target Race was not significant, F(1,100) = 0.001, p = .978, ηp2 < 0.001, but the effect of Target Clothing, F(1,100) = 45.044, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.311, and the interaction, F(1,100) = 50.479, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.335, were significant. As in Study 1, when targets were fully-clothed, Black women more animalistically dehumanized than White women, F(1,100) = 23.651, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.191, supporting H1. In this study, we also found support for the Hypothesis 2 when targets were scantily-clothed: White women were more animalistically dehumanized than Black women, F(1,100) = 27.028, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.213. Scantily-clothed women were more animalistically objectified than fully-clothed women when they were White, F(1,00) = 71.698, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.418, and to a lesser extent when they were Black, F(1,100) = 19.031, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.160.

Discussion

We again found significant interactions between Target Race and Clothing Type on all dependent variables in Study 2; Black and White women were differentially objectified depending on clothing type. We found that fully-clothed Black women were more likely to be objectified and animalistically dehumanized than fully-clothed White women, providing further support for the Black women default objectification hypothesis (H1). The race effect was not significant, however, for judgments of perceived appropriateness in this study.

Study 2 also provided initial evidence supporting the shifting sexuality standards hypothesis (H2): Scantily-clothed White women were more likely to be animalistically dehumanized and judged inappropriate than scantily-clothed Black women (the effect for objectification was in the same direction, though nonsignificant). The new scantily-clothed images used in Study 2 were clearly seen differently than those used in Study 1; for example, a comparison of the means in Tables 2 and 3 indicate that the new images were judged considerably less appropriate for advertising, presumably because the full-body images were more overtly sexual. Perhaps the shifting standards effect—contrasting judgments of White women from the lower expectations of sexuality—is more likely to occur with greater deviation from expectations (i.e., more evidence of overt sexuality). In Study 2, clothing type also continued to have a larger effect on judgments of White women than Black women.

Study 3

In Study 3, we sought to replicate our findings using a fully within-subjects design: White male participants viewed photos of all four types of women: Black and White, fully- and scantily-clothed. The change in design tests the generalizability of our effects across methodologies, and the fully within-subjects design offers more power by controlling for individual differences across perceivers. By virtue of viewing all types of stimuli, it is possible that men’s judgments will be more strongly differentiated by race and clothing type than in the previous studies, in which only fully-clothed or all scantily-clothed images were viewed. On the other hand, the new design might sensitize participants to the hypotheses and reduce this differentiation. We did not expect the methodological change to influence our results: Our hypotheses were identical to those outlined earlier. This study was pre-registered on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/x7zfy/?view_only=61733d8aab094f60a266a3629ce04270).

As in Studies 1 and 2, our main prediction was a statistical interaction between Target Race and Target Clothing on all dependent measures. Via simple effects analysis, we tested the Black women default objectification hypothesis (H1): Fully-clothed Black women would be more objectified, more animalistically dehumanized, and viewed less appropriate for various forms of media than fully clothed White women, and the shifting standards hypothesis (H2): Compared to scantily-clothed Black women, scantily-clothed White women would be more objectified, more animalistically dehumanized, and viewed as less appropriate.

Method

Participants

The sample size for this study was determined a priori based on a power analysis via G*Power (Faul et al., 2009) with a medium effect size (f = 0.25, error = 0.05, 0.95 power) for a 2 × 2 repeated measures design which indicated 74 participants. However, we used a new recruitment platform, Prolific (prolific.co) which often produces a higher exclusion rate than MTurk (i.e., 25.70%; see Peer et al., 2017). Therefore, we oversampled and obtained responses from 93 White men living in the United States. To verify participant race and gender, we used filters available via the platform and collected demographics at the end of the study. These participants ranged in age from 18 to 51 years (M = 24.19, SD = 7.23). No participants were excluded from analysis. A sensitivity power analysis in G*Power indicated that a sample of 93 participants was sufficient to detect a minimum effect size of f2 (1,91) = 0.251 or greater (α = 0.05, power = 0.80).

Design and Procedure

This study used a 2 (Target Race: Black, White) x 2 (Target Clothing: scantily-clothed, fully-clothed) repeated measures (fully within-subjects) design. In Study 3, we did not include filler photos, and participants evaluated 12, rather than eight, counterbalanced photos (three images of each type: scantily-clothed Black women, scantily-clothed White women, fully-clothed Black women, fully-clothed White women; the same set as used in Study 2). The total number of stimuli increased because we used a fully repeated measures design, maintaining three images of each type.

Dependent Measures

After viewing each image, participants indicated their agreement with the same dependent measures as in Studies 1 and 2: Appropriateness for advertising (αs ranged from 0.76 − 0.93 for each target, and from 0.65 to 0.93 for the composite indexes: scantily-clothed Black women = 0.93; scantily-clothed White women = 0.94; fully-clothed Black women = 0.88; fully-clothed White women = 0.85), sexual objectification (αs ranged from 0.77 to 0.82: scantily-clothed Black women = 0.78; scantily-clothed White women = 0.77; fully-clothed Black women = 0.72; fully-clothed White women = 0.82), and animalistic dehumanization (αs ranging from 0.79 to 0.90 for the individual targets and from 0.81 to 0.92 for the composites: scantily-clothed Black women = 0.78; scantily-clothed White women = 0.89; fully-clothed Black women = 0.61; fully-clothed White women = 0.82). No additional judgments or measures were included. Participants completed demographic questions before debriefing.

Results

A 2 (Target Race Black, White) x 2 (Target Clothing: Full, scant) repeated measures ANOVA was computed for each dependent variable. Means by condition appear in Table 4.

Appropriateness for Advertising

The target race effect was not significant, F(1, 92) = 0.240, p = .625, ηp2 = 0.004, but the main effect of target clothing, F(1, 92) = 169.953, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.649, and the predicted interaction, F(1, 92) = 6.977, p = .01, ηp2 = 0.070, were significant. As in Study 2, the race effect was not significant for fully-clothed targets: Black women were seen as equally appropriate to White women, F(1, 92) = 2.692, p = .104, ηp2 = 0.028, disconfirming Hypothesis 1. However, confirming Hypothesis 2, the shifting standards effect emerged; advertisements of scantily-clothed White women were viewed as less appropriate than those of scantily-clothed Black women, F(1, 92) = 4.246, p = .042, ηp2 = 0.044. Scantily-clothed women were also judged as less appropriate than fully-clothed women for White women, F(1, 92) = 146.695, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.615, and Black women, F(1, 92) = 160.577, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.636, but in this case the effect of clothing was somewhat stronger for Black women.

Sexual Objectification

The target race effect was not significant, F(1, 92) = 0.026, p = .871, ηp2 < 0.001, but the target clothing effect, F(1, 92) = 479.353, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.839, and the predicted interaction, F(1,92) = 49.035, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.348, were both significant. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, when the women were fully-clothed, Black women were more objectified than White women, F(1, 92) = 29.634, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.244, and consistent with Hypothesis 2, when the women were scantily-clothed, White women were more objectified than Black women, F(1, 92) = 23.709, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.205. Additionally, scantily-clothed White women were objectified more than fully-clothed White women, F(1, 92) = 470.656, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.836. The same pattern emerged for Black women, but the effect was somewhat less strong, F(1, 92) = 303.978, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.768.

Animalistic Dehumanization

All effects were significant: target race, F(1,92) = 0.309.611, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.771, target clothing, F(1, 92) = 18.723, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.169, and the interaction, F(1, 92) = 241.432, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.724. Again, consistent with predictions, when targets were fully-clothed (H1), Black women more animalistically dehumanized than White women, F(1, 92) = 374.954, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.803, and when targets were scantily-clothed (H2), White women were more animalistically dehumanized than Black women, F(1, 92) = 111.829, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.559. Scantily-clothed women were more animalistically objectified than fully-clothed women when they were White, F(1, 92) = 177.796, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.659, and to a lesser extent when they were Black, F(1, 92) = 49.345, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.349.

Discussion

Using a fully within-subjects design with preregistered predictions, Study 3 provided strong support for our two key hypotheses. Target Race x Target Clothing interactions were significant for all three dependent variables, and simple effects tests supported the Black women default objectification hypothesis (H1): Fully-clothed Black women were more objectified and more animalistically dehumanized compared to fully-clothed White women (though the effect on perceived appropriateness was not significant), and the shifting standards of sexuality hypothesis (H2): Scantily-clothed White women were more sexually objectified, more animalistically dehumanized, and viewed as less appropriate than scantily-clothed Black women.

One limitation of the first three studies is the nature of the stimuli. For ecological validity, we chose existing media images of women and attempted to equate them across race (on clothing, pose, expression) as best we could. But this meant a lack of precise control. To address this concern, in Study 4 we use new stimuli borrowed from Anderson et al. (2018). A second limitation of the first three studies was the single item measure of sexual objectification. This single item provides a face-valid global assessment of sexual objectification and has been used in previous research (Landau et al., 2012), but we added multi-item measures of sexual objectification that more directly tap into engagement with the target (e.g., sexually objectifying behaviors).

Study 4a

The goal of Study 4a was to examine whether effects replicated using a better-matched set of stimuli of Black and White, fully and scantily-clothed women (Anderson et al., 2018) and additional measures of sexual objectification. We also used a fully between-subjects to again test the generalizability of our effects across methods. Additional demographic and attitudinal measures were also included as potential moderators of objectification. This study was pre-registered on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/a7yqs/?view_only=a4d05a30a6e74A7aac38088f6ce389e3). As in the previous studies, we predicted a statistical interaction between Target Race and Target Clothing, such that when fully-clothed, Black women would be more sexually objectified than White women (Hypothesis 1), and when scantily-clothed, White women would be more sexually objectified than Black women (Hypothesis 2).

Method

Participants

The sample size was determined a priori based on a power analysis via G*Power (Faul et al., 2009) with a medium effect size (f = 0.25, error = 0.05, 0.95 power) for a 2 × 2 between-subjects design which suggested 210 participants. However, we pre-registered our strategy to oversample (25.70%) and obtain responses from 264 White men living in the United States, which we did. Five participants were removed for reporting confusion or difficulty understanding, 16 for completing the study on a cell phone, 11 for reporting being homosexual or preferring not to specify their sexuality. Three additional participants were removed for missing data, leaving a final sample of 230 White men who ranged in age from 18 to 75 years (M = 36.67, SD = 11.96). A sensitivity power analysis in G*Power indicated that a sample of 230 participants was sufficient to detect a minimum effect size of f2 (1,228) = 0.162 or greater (α = 0.05, power = 0.80).

Design and Procedure

This study adopted a 2 (Target Race: Black, White) x 2 (Target Clothing: scantily-clothed, fully-clothed) between-subjects design. White male participants evaluated a new set of three counterbalanced photos of either Black or White women who were either scantily or fully clothed. These images, sources from online retailers, have been used in previous research on objectification (Anderson et al., 2018). In all images the women stood in front of a white background and directly faced the camera. All images were matched for facial prominence (face, body proportion), and pre-testing assured equivalent attractiveness and expressiveness. We selected three images of each Targe Race x Target Clothing type for use in this study.

Dependent Measures

After viewing each image, participants indicated their agreement with the same dependent measures as in Studies 1–3: Appropriateness for advertising (αs ranged from 0.71 − 0.93 for each target, and from 0.75 to 0.94 for the composite indexes: scantily-clothed Black women α = 0.92; scantily-clothed White women α = 0.94; fully clothed Black women α = 0.91; fully clothed White women α = 0.75), the single-item measure of sexual objectification (scantily-clothed Black women α = 0.50; scantily-clothed White women α = 0.81; fully-clothed Black women α = 0.68; fully-clothed White women α = 0.79), and animalistic dehumanization (αs ranging from 0.86 to 0.94 for the individual targets and from 0.84 to 0.92 for the composites: scantily-clothed Black women α = 0.82; scantily-clothed White women α = 0.84; fully-clothed Black women α = 0.88; fully-clothed White women α = 0.92).

New to this study, participants also completed a six-item measure of behavioral sexual objectification (Gervais et al., 2018) in response to each stimulus (αs ranging from 0.88 to 0.96 for the individual targets and from 0.78 to 0.96 for the composites: scantily-clothed Black women α = 0.86; scantily-clothed White women α = 0.96; fully-clothed Black women α = 0.89; fully-clothed White women α = 0.78). Participants indicated their likelihood of engaging in six sexually harassing behaviors on a 7-point scale from 1 (Not at all likely) to 7 (Very likely): “When you see this model, how likely are you to. . stare at her breasts/chest when you are talking to her?; evaluate her physical appearance?; stare at her body?; leer at her body?; stare at one or more of her body parts?; and gaze at her body or a body part instead of listening to what she is saying.”

Also new to this study, after reviewing and rating all stimuli, participants indicated their overall sexual objectification/aggression (α = 0.95) on nine items from Gervais et al. (2018). Using the same 1–7 likelihood scale, participants were asked, “Considering each of the women from the group that you just saw, how likely would you: Whistle at her while she was walking down a street?; Make a rude sexual remark about her body?; Honk at her when she is walking down the street?; Make inappropriate sexual comments about her body?; Make sexual comments or innuendos when noticing her body?; Touch or fondle her against her will?; Perpetrate sexual harassment (on the job, in school, etc.)?; Grab or punch her private body areas against her will?; and Make a degrading sexual gesture toward her?” We were concerned that asking these questions after each stimulus would be burdensome, so they were asked only once at the end of the study after rating all three images.

Participants also completed demographic and attitudinal questions, including age, political orientation on a sliding scale from 0 (strongly liberal) to 100 (strongly conservative), relationship status (1 = Married, 2 = In a Relationship, 3 = Single; transformed into a 0 = in a relationship and 1 = single “single” metric), and social class (education, occupation, and income; standardized and combined into a social class index; α = 0.68). See Supplement E in the online supplement for the demographic analyses; there was no evidence that these demographics moderated Target Race x Target Clothing effects.

Results

A 2 (Target Race: Black, White) x 2 (Target Clothing: fully-clothed, scantily-clothed) between-subjects ANOVA was computed for each dependent variable. Means by condition appear in Table 5.

Appropriateness for Advertising

The target race effect was not significant, F(1, 229) = 1.373, p = .243, ηp2 = 0.006, but the main effect of target clothing, F(1, 229) = 60.503, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.209, and the predicted interaction, F(1, 229) = 4.212, p = .041, ηp2 = 0.018, were significant. Simple effects tests indicated support for Hypothesis 1: Advertisements of fully-clothed Black women were viewed as less appropriate than those of fully-clothed White women, F(1, 229) = 5.127, p = .024, ηp2 = 0.022. However, the race effect was not significant for scantily-clothed targets: Black and White women were seen as equally low in appropriateness, F(1, 229) = 0.393, p = .531, ηp2 = 0.002, so H2 was not supported. Scantily-clothed women were also judged as less appropriate than fully-clothed both when the women were White, F(1, 229) = 48.992, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.176, and Black, F(1, 229) = 16.172, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.066, but as in most prior cases, the effect of clothing was stronger for White women.

Single-Item Sexual Objectification and Animalistic Dehumanization

For these measures, there was a significant main effect of target clothing on sexual objectification, F(1, 229) = 90.757, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.284, and animalistic dehumanization, F(1, 229) = 32.164, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.123. Neither the race effects nor the interactions were significant, ps > 0.292. Scantily-clothed women were more objectified and dehumanized than fully-clothed women, but we found no support for either H1 or H2 on these measures.

Behavioral Sexual Objectification

On the multi-item measure of sexual objectification behaviors, the predicted interaction was significant, F(1, 229) = 4.646, p = .032, ηp2 = 0.02, as was the main effect of target clothing, F(1, 229) = 43.855, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.161, but not target race, F(1, 229) = 1.307, p = .254, ηp2 = 0.006. Consistent with the shifting standards hypothesis (H2), when targets were scantily-clothed, White women more sexually objectified than Black women, F(1, 229) = 5.516, p = .02, ηp2 = 0.024. However, H1 was not supported: When targets were fully-clothed, Black and White women were equally sexually objectified, F(1, 229) = 0.505, p = .478, ηp2 = 0.002. Scantily-clothed women were more sexually objectified than fully-clothed women when they were White, F(1, 229) = 39.059, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.146, and to a lesser extent when they were Black, F(1, 229) = 9.842, p = .002, ηp2 = 0.041.

Overall Sexual Objectification/Aggression

The mean on the index of sexual objectification/aggression, measured after viewing all images, was very low, M = 1.63 on a 1–7 scale, SD = 1.17. In light of this, none of the effects were significant: Target clothing F(1, 229) = 1.451, p = .230, ηp2 = 0.006, Target Race F(1, 229) = 0.131, p = .718, ηp2 0.001, and the interaction F(1, 229) = 1.024, p = .313, ηp2 = 0.004.

Discussion

Study 4a provides additional evidence that Black and White women are differentially objectified and viewed as appropriate for media use depending on their clothing. We used a multi-item measure of sexual objectification, as well as a fully between-subject’s design to test the predicted Target Race x Target Clothing interactions.

On perceived appropriateness, we found evidence for Hypothesis1, in that fully-clothed Black women were viewed as less appropriate than fully-clothed White women, but not for Hypothesis2. On the single-item measure of sexual objectification and animalistic dehumanization, we did not replicate the interactions found in the prior studies; only main effects of target clothing emerged with this between-subject design. However, the predicted interaction did emerge on the new multi-item behavioral measure of sexual objectification. In this case, simple effects tests supported Hypothesis 2, with White women more sexually objectified than Black women when scantily-clothed, but not Hypothesis 1, as there was no target race difference in behavioral sexual objectification rates when women were fully-clothed.

The change in Study 4a to a fully between-subjects design may have limited our ability to detect Target Race x Target Clothing effects on objectification and animalistic dehumanization, even though we achieved the recommended sample size based on a power analysis. It is also possible that the partially or fully within-subjects designs of the previous study (in which men could explicitly compare Black and White women and in Study 3, fully- and scantily-clothed women) are important for reliably producing the predicted effects. However, the new multi-item measure of sexual objectification (Gervais et al., 2013) did reveal the predicted interaction, suggesting that the change in images alone was not responsible for the differences with prior studies.

Study 4b

The goal of Study 4b was to test our hypotheses in a sample of Black male participants, using the same procedures as Study 4a. We included this study to assess the generalizability of our effects beyond White male samples, and to consider an ingroup bias account of our findings—that men sexually objectify women of their own race when sexual cues are present but sexually objectify women of an outgroup race in more neutral contexts. The target race effects reported in the first four studies could have more to do with race of the perceiver than general sexual stereotypes about Black and White women. We predict, however, that Black men will demonstrate the same judgment patterns as White men (see H1 and H2), given the shared consensual nature of racialized sexual stereotypes of women. This study was pre-registered on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/jrq6b/?view_only=eed1f0b09c744685bf1ae42cff7544e0).

Method

Participants

The same power analysis described in Study 4a applied to this study (suggested N = 210). We pre-registered our strategy to oversample (25.70%) and obtain responses from 264 Black men living in the United States using Prolific. We ultimately obtained responses from 267 Black men. One participant was removed for reporting being female, seven for not identifying as Black in the ethnicity check, one for reporting confusion or difficulty understanding instructions, 18 for completing the study on a cell phone, 11 for reporting being gay or preferring not to specify their sexuality, 32 for having a duplicate IP address (first responses were maintained), and nine for missing data. This left a final sample of 188 Black men who ranged in age from 18 to 79 years (M = 33.57, SD = 11.10). While it may appear that this study was underpowered, a sensitivity power analysis via G*Power indicated that a sample of 188 participants was sufficient to detect a minimum effect size of f2 (1,186) = 0.179 or greater (α = 0.05, power = 0.80).

Design and Procedures

This study used the same design and procedures in Study 4a.

Dependent Measures

After viewing each image, participants indicated their agreement with the same dependent measures as in Studies 1-4a: Appropriateness for advertising (αs ranged from 0.80 − 0.96 for each target, and from 0.76 − 0.98 for the composite indexes: scantily-clothed Black women α = 0.91; scantily-clothed White women α = 0.98; fully clothed Black women α = 0.83; fully clothed White women α = 0.76), the single-item measure of sexual objectification (αs ranged from 0.69 to 0.79: scantily-clothed Black women α = 0.78; scantily-clothed White women α = 0.79; fully clothed Black women α = 0.69; fully clothed White women α = 0.73). animalistic dehumanization (αs from 0.85 to 0.92 for the individual targets and 0.84 – 0.91 for the composites: scantily-clothed Black women α = 0.84; scantily-clothed White women α = 0.91; fully-clothed Black women α = 0.85; fully-clothed White women α = 0.89), behavioral sexual objectification (αs ranged from 0.87 to 0.94 for the individual targets and 0.87 – 0.95 for the composites: scantily-clothed Black women α = 0.95; scantily-clothed White women α = 0.95; fully clothed Black women α = 0.87; fully-clothed White women α = 0.89), and overall sexual objectification/aggression (α = 0.93). Participants also completed the same demographic question as in study 4a and were then debriefed. See Supplement E in the online supplement for the exploratory analysis of the demographic questions.

Results

For each dependent variable, we computed a 2 (Race of target: Black, White) x 2 (Target Clothing: Full, scant) between-subjects ANOVAs. Means by condition appear in Table 6.

Appropriateness for Advertising

The target race effect was not significant, F(1, 184) = 2.323, p = .129, ηp2 = 0.012, but the main effect of target clothing, F(1, 184) = 32.549, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.15, and the predicted interaction, F(1, 184) = 7.785, p = .006, ηp2 = 0.041, were significant. Simple effects tests supported Hypothesis 2 in that scantily-clothed White women were seen as less appropriate than scantily-clothed Black women, F(1, 184) = 9.114, p = .003, ηp2 = 0.05. Hypothesis 1 was not supported; advertisements of fully-clothed Black women were viewed as equally appropriate as the advertisements of fully-clothed White women, F(1, 184) = 0.818, p = .367, ηp2 = 0.004. Scantily-clothed targets were also judged less appropriate than full clothing both when the women were White, F(1, 184) = 35.72, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.163, and Black, F(1, 184) = 4.293, p = .04, ηp2 = 0.023, but as in the prior studies, the effect of clothing was stronger for White targets.

Single-Item Sexual Objectification

Only the main effect of target clothing was significant, F(1, 184) = 69.124, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.273. Scantily-clothed women were more objectified than fully-clothed women. Neither the race effect, F(1, 184) = 0.959, p = .329, ηp2 = 0.005, nor the interaction, F(1, 184) = 0.004, p = .948, ηp2 = 0.001, were significant; therefore, neither hypothesis was supported on this dependent variable.

Animalistic Dehumanization

On the measure of animalistic dehumanization, the predicted interaction was significant, F(1, 184) = 5.156, p = .044, ηp2 = 0.027, as was the main effect of target clothing, F(1, 184) = 51.712, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.219, and target race, F(1, 184) = 6.86, p = .01, ηp2 = 0.036. Consistent with the shifting standards prediction (H2), when targets were scantily-clothed, White women more sexually objectified than Black women, F(1, 184) = 11.709, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.06. However, counter to H1, when targets were fully-clothed, Black and White women were equally sexually objectified, F(1, 184) = 0.062, p = .804, ηp2 < 0.001. Scantily-clothed women were more sexually objectified than fully-clothed women when they were White, F(1, 184) 44.311, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.194, and to a lesser extent when they were Black, F(1, 184) = 12.230, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.062.

Behavioral Sexual Objectification

On the multi-item measure of sexual objectification behaviors, the predicted interaction was significant, F(1, 184) = 4.548, p = .034, ηp2 = 0.024, as was the main effect of target clothing, F(1, 184) = 49.614, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.212, but not the target race effect, F(1, 184) = 2.206, p = .139, ηp2 = 0.012. Again, consistent with shifting standards predictions, when targets were scantily-clothed, White women more sexually objectified than Black women, F(1, 184) = 6.409, p = .012, ηp2 = 0.034. However, when targets were fully-clothed, Black and White women were equally sexually objectified, F(1, 184) = 0.214, p = .644, ηp2 = 0.001. Scantily-clothed women were more sexually objectified than fully-clothed women when they were White, F(1, 184) = 41.677, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.185, and to a lesser extent when they were Black, F(1, 184) = 12.184, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.062.

Overall Sexual Objectification/Aggression

As in Study 4a, the mean on this index of sexual objectification/aggression, measured at the end of the study, was very low (M = 1.84 on a 1–7 scale, SD = 0.60), and none of the effects were significant: Target clothing F(1, 184) = 0.027, p = .87, ηp2 < 0.001, target race F(1, 184) = 0.247, p = .620, ηp2 = 0.001, and Target Race x Target Clothing interaction F(1, 184) = 0.264, p = .608, ηp2 = 0.001.

Comparing Judgments of Black and White Men

Studies 4a and 4b were conducted separately, roughly 6 months apart, and therefore we felt they should be treated as separate samples. However, we did combine the two data sets, and re-ran all analyses with participant race as an additional effect (including all interactions). Across the five dependent variables, participant race never moderated the critical Target Race x Target Clothing interactions (all ps > 0.16), and the only significant effects of participant race were main effects on three of the variables (White men scored higher overall than Black men in animalistic dehumanization and behavioral sexual objectification; Black men scored slightly higher than White men on the overall sexual objectification measure).

Discussion

Study 4b provides evidence that Black men differentially objectify and dehumanize women based on their race and clothing. We found clear evidence supporting Hypothesis2 on the measures of appropriateness, animalistic dehumanization, and sexual objectification. Black men judged scantily-clothed White women as less appropriate than scantily-clothed Black women and were more likely to sexually objectify and animalistically dehumanize them. Black men also judged scant clothing as less appropriate than full clothing among both White and Black women, but this effect was stronger for White women. This provides evidence that the shifting standards effect was not due to an ingroup favoritism effect (Anzures et al., 2013); rather Black men showed parallel responses to White men for their ratings of sexualized Black and White women.

However, unlike the prior studies conducted with White male perceivers (Studies 1-4a) we did not find any evidence for Hypothesis 1 among Black male perceivers. There was no difference in perceived appropriateness, animalistic dehumanization, or sexual objectification rates between fully-clothed Black and White women. White men may be more likely than Black men to endorse sexualized stereotypes that lead them to sexually objectify Black women in non-sexualized contexts (though it is worth noting that this pattern was weaker even among White men in Study 4a), but the combined analysis showed no moderation of responses by participant race.

The fully between-subjects designs in Studies 4a and 4b did not replicate the Race x Clothing interaction on the single-item measure of sexual objectification, and generally showed weaker support for Hypothesis 1. This suggests that explicit cross-race and/or cross-clothing type comparisons may be necessary for the full pattern of predicted effects to emerge.

Internal Meta-Analysis

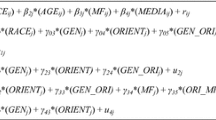

Across studies and dependent measures, we consistently found evidence for Target Race x Clothing type interactions, but the more focused simple effects hypothesis tests were a bit less consistent. To synthesize our results, we conducted an internal meta-analysis across our five studies, testing particularly for the overall effect size of the two key predictions: The Black woman default objectification hypothesis (Black women will be more objectified than White women when fully clothed; H1), and the shifting standards hypothesis (White women will be more objectified than Black women when scantily-clothed; H2). We also examined the effects of clothing type (sexual objectification of scantily-clothed versus fully-clothed women) in Black and White women, for four effects in each of the five studies (representing the four simple effects tests from the Target Race x Target Clothing interactions). Meta-analytic procedures assume that effect sizes are independent, but we have multiple correlated dependent measures in each study and including each separately violates this assumption of independence. We therefore followed convention and combined the appropriateness (reverse scored), objectification, and animalistic dehumanization variables (the outcomes common to all studies) within each study; in this way, each study contributed one estimate for each of the effects described above.

Using Excel-based workbooks for meta-analysis by Suurmond et al. (2017), for each study, we computed four effect sizes along with the overall meta-analytic effect size (Cohen’s d). Results are summarized in Table 7. The Black woman default objectification effect (H1) was d = 0.45 (95% CI = 0.06, 0.83): fully-clothed Black women were objectified more than fully-clothed White women. The shifting standards effect (H2) was d = − 0.42, (95% CI = − 0.62, − 0.22): scantily-clothed White women were sexually objectified more than Black women. The absolute values of these two effect sizes did not differ, z = 0.12, p = .9045; we therefore conclude that meta-analytically, support for the two hypotheses was equally strong. Finally, scantily-clothed women were objectified more than fully-clothed women, though more so when the women were White, d = 2.16 (95% CI = 1.20, 3.13), than Black, d = 1.41 (95% CI = 0.66, 2.16), z = 3.00, p = .003.

General Discussion

This research demonstrates how men from racially dominant (e.g., White American) and minoritized groups (e.g., Black American) differentially objectify and dehumanize Black and White women depending on the clothing context. The five studies converge to provide support for the Black women default objectification account (H1): White male perceivers were more likely to associate sexuality with Black women in situations that were not overtly sexual. Specifically, images of fully-clothed Black women were viewed as less appropriate for advertising, were more sexually objectified, and were more animalistically dehumanized than images of fully-clothed White women (though this pattern was not significant in the fully between-subjects Study 4a and Study 4b with Black participants). Studies 2, 3, 4a, and 4b provided support for the shifting standards hypothesis of sexuality (H2). Images of scantily-clothed White women were viewed as less appropriate, were more sexually objectified, and were more animalistically dehumanized relative to images of scantily-clothed Black women. The internal meta-analysis also supported both hypotheses, with similar effect sizes for H1: the Black women default objectification hypothesis (d = 0.45) and H2: the shifting standards hypothesis (d = − 0.42). Additionally, clothing type mattered for judgments of both Black and White women but was stronger for judgments of White women: The men in our samples showed greater sensitivity to contextual clothing cues in White than Black women.

The present research extends discourse on the sexual objectification of women by identifying the differential impact of clothing depending on target race and showing that in the context of visual imagery and media advertisements, race-based shifting standards may affect objectification outcomes. Our findings point to the importance of addressing racialized gender stereotypes in social discourse—particularly the pervasive hypersexual portrayals of Black women in music videos, movies, and reality television (Ramsey & Horan, 2018; Stephens & Phillips, 2005; West, 2008). Our studies used static representations of women, but we suspect that our findings may extend to more dynamic and richer forms of media and social interaction (Landau et al., 2012), including interpersonal sexual objectification experiences that can take place online and in person.