Abstract

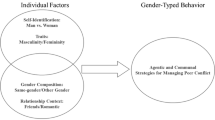

Using hypothetical vignettes, we investigated the extent to which gender differences in conflict-management strategies depended on the relationship context of a same-gender friendship vs. a romantic relationship. Associations between conflict-management strategies, goals and gender-typed traits also were assessed. Men (131) and women (203) undergraduate students (19–25 years) from a state university in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States participated. To assess expressive and instrumental personality traits, participants completed the Personal Attributes Questionnaire (PAQ; Spence and Helmreich 1978). Participants also rated their endorsement of communal and agentic goals and strategies for managing hypothetical conflicts presented in the “Peer Conflict Management Questionnaire.” This questionnaire, created for the purposes of this study, consisted of 4 vignettes that portrayed hypothetical conflicts with a friend and a romantic partner. Results showed that women were more likely than men to endorse communal strategies when managing conflict with a same-gender friend, but not with a romantic partner. Women were more likely than men to endorse agentic strategies for managing conflict with a romantic partner, but not with a same-gender friend. For conflicts with a same-gender friend, communal goals, but not expressive traits or gender, predicted communal strategy endorsement. For conflicts with a romantic partner, gender and agentic goals predicted agentic strategies; instrumental traits did not. Implications for understanding consequences of gender-typed relationship processes are discussed. The contextual specificity of gender differences and similarities are emphasized.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480. doi:10.1037//0003-066X.55.5.469.

Bakan, D. (1966). The duality of human existence: An essay on psychology and religion. Oxford: Rand McNally.

Bem, S. L. (1974). The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42, 155–162. doi:10.1037/h0036215.

Berg, C., & Strough, J. (2010). Problem solving across the lifespan. In K. Fingerman, C. A. Berg, T. Antonnuci, & J. Smith (Eds.), Handbook of lifespan psychology (pp. 239–268). New York: Springer.

Black, K. (2000). Gender differences in adolescents’ behavior during conflict resolution tasks with best friends. Adolescence, 35, 499–512.

Buhrmester, D. (1990). Intimacy of friendship, interpersonal competence, and adjustment during preadolescence and adolescence. Child Development, 61, 1101–1111. doi:10.2307/1130878.

Buhrmester, D. (1996). Need fulfillment, interpersonal competence, and the developmental contexts of early adolescent friendship. The company they keep: Friendship in childhood and adolescence (pp. 158–185). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Carver, K., Joyner, K., & Udry, J. R. (2003). National estimates of adolescent romantic relationships. In P. Florsheim (Ed.), Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior (pp. 23–56). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Constantinople, A. (1973). Masculinity-femininity: An exception to a famous dictum? Psychological Bulletin, 80, 389–407. doi:10.1037/h0035334.

Creasey, G., Kershaw, K., & Boston, A. (1999). Conflict management with friends and romantic partners: The roles of attachment and negative mood regulation expectancies. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 28, 523–543. doi:10.1023/A:1021650525419.

Deaux, K., & Major, B. (1987). Putting gender into context: An interactive model of gender related behavior. Psychological Review, 94, 369–389. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.369.

Eagly, A. (1987). Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Eldridge, K. A., & Christensen, A. (2002). Demand-withdraw communication during couple conflict: A review and analysis. In P. Noller & J. A. Feeney (Eds.), Understanding marriage: Developments in the study of couple interaction (pp. 289–322). New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511500077.016.

Feingold, A. (1994). Gender differences in personality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 429–456. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.429.

Feiring, C. (1999). Other-sex friendship networks and the development of romantic relationships in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 28, 495–512. doi:10.1023/A:1021621108890.

Feldman, S. S., & Gowen, L. K. (1998). Conflict negotiation tactics in romantic relationships in high school students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 27, 691–717. doi:10.1023/A:1022857731497.

Furman, W., Simon, V. A., Shaffer, L., & Bouchey, H. A. (2002). Adolescents’ working models and styles for relationships with parents, friends, and romantic partners. Child Development, 73, 241–255. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00403.

Gottman, J. M., Coan, J., Carrere, S., & Swanson, C. (1998). Predicting marital happiness and stability from newlywed interactions. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60, 5–22. doi:10.2307/353438.

Huston, A. C. (1983). Sex-typing. In E. M. Hetherington (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 4. Socialization, personality, and social development (pp. 387–467). New York: Wiley.

Hyde, J. S. (2005). The gender similarities hypothesis. American Psychologist, 60, 581–592. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.6.581.

Jensen-Campbell, L. A., Graziano, W. G., & Hair, E. C. (1996). Personality and relationships as moderators of interpersonal conflict in adolescence. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 42, 148–164. Retrieved from http://www.asu.edu/clas/ssfd/mpq.

Kurdek, L. A. (2005). What do we know about gay and lesbian couples? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 251–254. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00375.x.

Laursen, B., Finkelstein, B. D., & Townsend Betts, N. (2001). A developmental meta-analysis of peer conflict resolution. Developmental Review, 21, 423–449. doi:10.1006/drev.2000.0531.

Leaper, C. (1994). Exploring the consequences of gender segregation on social relationships. In C. Leaper (Ed.), Childhood gender segregation: Causes and consequences (pp. 67–86). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Leaper, C., Carson, M., Baker, C., Holliday, H., & Myers, S. (1995). Self-disclosure and listener verbal support in same-gender and cross-gender friends’ conversations. Sex Roles, 33, 387–404. doi:10.1007/BF01954575.

Leszczynski, J. P., & Strough, J. (2008). Contextual specificity of masculinity and femininity. Social Development, 17, 719–736. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00443.x.

Lindeman, M., Harakka, T., & Keltikanga-Jarvinen, L. (1997). Age and gender differences in adolescents’ reactions to conflict situations: Aggression, prosociality, and withdrawal. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 26, 339–351. doi:10.1007/s10964-005-0006-2.

Maccoby, E. E. (1998). The two sexes: Growing up apart, coming together. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Maccoby, E. E. (2000). Perspectives on gender development. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 4, 398–406. doi:10.1080/016502500750037946.

Mead, M. (1935). Sex and temperament in three primitive societies. Oxford: William Morrow.

Mehta, C. M., & Strough, J. (2009). Sex segregation in friendships and normative contexts across the life span. Developmental Review, 29, 201–220. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2009.06.001.

Monsour, M. (2002). Women and men as friends: Relationships across the life span in the 21st century. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Pickard, J., & Strough, J. (2003). Variability in goals as a function of same-sex and other-sex contexts. Sex Roles, 49, 643–652. doi:10.1023/B:SERS.0000003134.59267.82.

Reese-Weber, M., & Marchland, J. F. (2000). Family and individual predictors of late adolescents’ romantic relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31, 197–206. doi:10.1023/A:1015033219027.

Rose, A. J., & Asher, S. R. (1999). Children’s goals and strategies in response to conflicts within a friendship. Developmental Psychology, 35, 69–79. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.35.1.69.

Rose, A. J., & Rudolph, K. D. (2006). A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 98–131. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98.

Sorkin, D. H., & Rook, K. S. (2006). Dealing with negative social exchanges in later life: Coping responses, goals, and effectiveness. Psychology and Aging, 21, 715–725. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.21.4.715.

Spence, J. (1993). Gender-related traits and gender ideology: Evidence for a multifactorial theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 624–635. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.64.4.624.

Spence, J. T., & Helmreich, R. L. (1978). Masculinity and femininity: Their psychological dimensions, correlates and antecedents. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Spence, J., & Helmreich, R. (1981). Androgyny versus gender schema: A comment on Bem’s gender schema theory. Psychological Review, 88, 365–368. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.88.4.365.

Sternberg, R. J. (1987). Liking versus loving: A comparative evaluation of theories. Psychological Bulletin, 102, 331–345. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.102.3.331.

Strough, J., & Berg, C. (2000). Goals as a mediator of gender differences in high-affiliation dyadic conversations. Developmental Psychology, 36, 117–125. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.36.1.117.

Strough, J., & Keener, E. (in press). Interpersonal problem solving across the life span. In P. Verhaeghen & C. Hertzog (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of emotion, social cognition, and everyday problem solving during adulthood. The Oxford Library of Psychology Series, Oxford University Press.

Strough, J., Berg, C. A., & Sansone, C. (1996). Goals for solving everyday problems across the life span: Age and gender differences in the salience of interpersonal concerns. Developmental Psychology, 32, 1106–1115. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.32.6.1106.

Strough, J., Leszczynski, J. P., Neely, T. L., Flinn, J. A., & Margaret, J. (2007). From adolescence to later adulthood: Femininity, masculinity, and androgyny in six age groups. Sex Roles, 57, 385–396. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9282-5.

Strough, J., McFall, J. P., Flinn, J. A., & Schuller, K. L. (2008). Collaborative everyday problem solving among same gender friendships in early and later adulthood. Psychology and Aging, 23, 517–530. doi:10.1037/a0012830.

Suh, E. J., Moskowitz, D. S., Fournier, M. A., & Zuroff, D. C. (2004). Gender and relationships: Influences on agentic and communal behaviors. Personal Relationships, 11, 41–59. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2004.00070.x.

Twenge, J. M. (1997). Changes in masculine and feminine traits of over time: A meta-analysis. Sex Roles, 36, 305–325. doi:10.1007/BF02766650.

Twenge, J. M. (1999). Mapping gender. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 23, 485–502. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1999.tb00377.x.

Unger, R. (1979). Toward a redefinition of sex and gender. American Psychologist, 34, 1085–1094. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.34.11.1085.

Whiting, B., & Edwards, C. P. (1988). A cross-cultural analysis of gender differences in the behavior of children aged 3 through 11. In G. Handel (Ed.), Childhood socialization (pp. 281–297). Hawthorne: Aldine de Gruyter.

Zarbatany, L., McDougall, P., & Hymel, S. (2000). Gender-differentiated experience in the peer culture: Links to intimacy in preadolescence. Social Development, 9, 62–79. doi:10.1111/1467-9507.00111.

Zirkel, S., & Cantor, N. (1990). Personal construal of life tasks: Those who struggle for independence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 172–185. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.58.1.172.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Andrea Strope, Emily Craun, Michelle Harris, Brittany Hubbard, Matt Basil, Hong Zhi Zou, Kristie Young, and Whitney DeBolt for their work on this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix

Below, to conserve space, we present vignettes only once. However, participants in the current study were presented with the romantic partner wording or the same-gender friend wording depending on the section of the questionnaire (see wording in italics).

Conflict Vignettes

Vignette 1

You are at the library working on a term paper that is due tomorrow. You have worked hard all year and you need a good grade. Your boyfriend/girlfriend (best friend) sends you a message telling you that his/her computer just crashed. Despite trying everything your boyfriend/girlfriend (best friend) has lost all of his/her work for an important project that is due tomorrow. Your boyfriend/girlfriend (best friend) has worked hard all year, but still needs a good grade on this project to do well in the class and you are the only person that can help. Although you and your boyfriend/girlfriend (best friend) often help each other, you will not have time to help your boyfriend/girlfriend (best friend) and do your own work.

Vignette 2

You and your boyfriend/girlfriend (best friend) want to do something together on Saturday and you both agree that it would be fun to go to a concert. There are two different bands playing on Saturday. One is your favorite; the other is your boyfriend/girlfriend’s (best friend’s) favorite. You cannot agree on which one to attend. You cannot go to both concerts, only one of you will get to see the band that they most want.

Vignette 3

You and your boyfriend/girlfriend (best friend) have just completed a major accomplishment (e.g., graduation). In response to this event your family has decided to throw you a party and have set a time and date that will work for most of the important members of your family to attend. Your boyfriend/girlfriend’s (best friend’s) parents are also going to throw him/her a similar party. However, when you tell your boyfriend/girlfriend (best friend) the date and time of your party, you both realize that each of your parents has picked the same day and time to hold each of the parties. You both hang out in the same group of friends. You both want all of your friends to be able to attend your party and also want to attend each other’s parties. Thus, one of you will have to change the date of your party.

Vignette 4

You and your boyfriend/girlfriend (best friend) want to spend spring break together and you both agree that it would be fun to go on a trip. There are two popular locations this year. One is your first choice; the other is your boyfriend/girlfriend’s (best friend’s) first choice. You cannot agree on which trip to take. You cannot take both trips, only one of you will get to go on the trip that they most want.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Keener, E., Strough, J. & DiDonato, L. Gender Differences and Similarities in Strategies for Managing Conflict with Friends and Romantic Partners. Sex Roles 67, 83–97 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-012-0131-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-012-0131-9