Abstract

Ah, emojis ☺. Some enthusiastically speak of them as a new universal language. In 2015, the Oxford English dictionary crowned one of them as its word of the year. Sixty million are exchanged daily on Facebook. Along with emoticons and various other smileys, emojis are now part of daily communications. Visual add-ons or superscript, they are meant to indicate intent or add emotions to written messages, which do not benefit from the tone or body language of the interlocutor. As such, they present themselves as tools for clarification, but one can wonder if they do not, too, introduce uncertainty in language. Aimed at barristers as well as jurilinguists, this paper seeks to underline some design and perception biases that can hinder communication, with a focus on rules of evidence and legal methodology. Empirically rooted in Canadian case law, the findings resonate in other jurisdictions, as emojis, indeed, are a global phenomenon.

Résumé

Les plus enthousiastes en parlent comme d’une nouvelle langue. Mot de l’année 2015 pour le dictionnaire Oxford, il s’en utilise environ soixante millions par jour seulement sur Facebook. Émojis, binettes, émoticônes: autant d’aides visuels à la communication devenus usuels. Alors qu’on les donne pour plus clairs que le texte seul, qui ne rend pas l’expressivité faciale ou la gestuelle du locuteur, on peut se demander s’ils ne contribuent pas, parfois, eux aussi à introduire une part d’incertitude dans le discours. Assurément, plaideurs autant que jurilinguistes doivent prendre conscience de certains biais de conception (notamment sur le plan des normes informatiques internationales) et de perception qui peuvent nuire à la communication, particulièrement en matière de preuve et de méthodologie de la recherche. Le caractère véritablement mondial des émojis permet de penser que les considérations théoriques soulevées par le présent article, trouvent appui au-delà de la jurisprudence canadienne qui l’illustre.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For a concise explanation, see Hern [138].

Tresierra [67], defines emoticons in passing, at para. 36, as “symbols with faces displaying an emotion.” The Merriam-Webster Dictionary, online, defines them as “a group of keyboard characters (such as :-)) that typically represents a facial expression or suggests an attitude or emotion and that is used especially in computerized communications (such as email),” a definition quoted in a number of American cases: Cochran [78], at n.1; Jacques [82], at n. 2; Shinn [79], at n. 4; Ghanam [75], at n. 4 (also quoting UrbanDictionary.com).

An addition to the June 2001 printed edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, the emoticon is therein defined as “A representation of a facial expression formed by a short sequence of keyboard characters (usually to be viewed sideways) and used in electronic mail, etc., to convey the sender’s feelings of intended tone” with a January 28, 1990 New York Times article credited as the first recorded use.

Japanese substantives do not take the mark of the plural. The English language usually accepts both the English and the foreign plural (a forum, many fora or many forums, a expresso, many expressi or expressos, a tsunami, more than one tsunami or tsunamis). Considering how many emojis are exchanged daily.

Though arguably some software converts emoticons to pictographs, for instance, Ms Word changes the combination of a semicolon and a closing parenthesis :) into a single circled smiling face ☺.

Unicode Consortium, “About” [174].

Nakano [154].

Unicode Consortium, “Basic Questions” [175].

Unicode Consortium, “Emoji and Pictographs” [176]; note also that a number of private parties also developed non-Unicode-backed sets of pictographs, all proprietary, brands (Star Wars, Ikea, the Major League Baseball, the National College Athletic Association), celebrities (Kim Kardashian, Lady Gaga, Ellen DeGeneres, Wiz Khalifa), institutions (The Washington Post, the New York Yankees), causes (Climoji for climate change): these are exchanged as images or are only available to recipients who have also downloaded the application. These are absent for Canadian case law and are excluded from our study. Relatedly, some Unicode-backed emojis are proprietary, such as Apple’s or Microsoft’s; others are open source, such as Twitter’s Twemojis or EmojiDex’s. On related intellectual property considerations, see: Bich-Carrière [86]; for an American perspective on the topic, see Goldman, 2018 [89] and Scall [94].

Most of these expressions are inaccurate in that they suggest that emojis and emoticons are limited to faces, and positive ones too. While it is true that three quarters of emojis used on mainstream social media in fact represent faces and that most are smiling (infra n. 46), emojis cover a much wider range, and include an array of animals, food, places, symbols, flags, etc. Even emoticons present non-facial combinations, such as the rose, @} ->, the heart<3 (which became litigious in the DVF Studio, LLC and Gap Inc. v. VeryMeri Creative Media NYSDC 1:13-cv-08943 file) or the penis, 8=D (the emoticon was featured in a 2017 short film 8=D by Philippe Morel et al., crowned with an award for best scenario at Spasm Festival in Montreal).

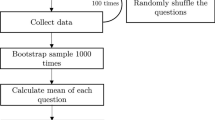

CanLII was used as primary database, with searches conducted in both English and French. Quicklaw and Westlaw were used to crosscheck results. The latter also yielded one older board decision, not reported on CanLII.

The breakdown of the main keywords is as follows: 20 “emoji” (including one misspelled “imoji”); 52 “emoticon” (or “émoticône”): 43 “smiley face”; 21 others. The total is greater than 115 as some decisions include more than one keyword or a combination thereof (e.g. Big Bag of Cash Contest [13], and Grant [52], referring to both emojis and emoticons but meaning only, respectively, emoji and emoticon; ME [32]), at para. 61 [“happy face symbol/emoticon”], Hamdan [53], at para. 81 [“a smiley face emoticon”] or M.B. [56], at para. 91 [[“a smiley face emoticon”]; B.F. [43], at para. 5 [“a smiley face emoji”]; Grant [52], at para. 194 [[“a smiley face emoji”]; McCall [58], at para. 9 [“smiley face emoticon symbol”]. Two decisions in the same file were counted as one if the relevant text was identical (e.g., McCall [58] on verdict and McCall [57] on sentencing), as two if the reasons were different (e.g., Hamilton v Crêpe it Up! [24] and Crêpe It Up! v Hamilton [17]).

We note that earlier decisions were indexed on some of the consulted databases after this paper was submitted. These were not included.

E.g., “WhatsApp” 85 yields decisions since Group of Employees [23], published on 18 November 2013; “Skype,” 2,824 decisions since Ben-Tzvi [7] published on 21 July 2006 and “Facebook,” 7,473 decisions since W.R.V. [75] published on 28 August 2007. We take some comfort in professor Eric Goldman [89]’s work sheets: working on American case law –a much bigger case pool due to the respective populations of Canada and the United States–but similarly aiming to conduct an exhaustive survey, his inventory yields 87 cases from 6 August, 2004 to 13 February, 2017. For the same period, our survey gives 79 results.

See e.g., Wilson [96], at pp. 79–80.

Though an increasing trend was documented by Porter [92], at p. 1718.

Picard [39], at para. 29, translation is ours.

C.V. II [9], translation is ours.

Hungry? Why don’t you type in a ticket or a pizza emoji and let Yelp! or Google give you directions to the nearest joint or movie theatre? Certain domain name providers also allow one to add an emoji to a URL address: see Johnson [142].

For instance, in Maughan (Sup. Ct) [34], the impugned emoticon is both reproduced and described as a “smiley face icon,” whereas the confirmatory judgment, Maughan (App. Ct.) [35], only reproduces the impugned emoticon, without any descriptive expression being used, and was thus not included in the count. Other examples of decisions featuring emoticons without mention of the keyword include a “: p” in Ngai [61], at para. 146 and a “=)” in K.C. [27], at para. 18. These were excluded from the results.

The reasons in Dhandhukia [48], expressly state, at para. 4, that “a copy of the transcript [is attached] as Appendix A to these reasons. It contains several symbols that were described as various types of ‘smiley faces.’”; however, no such transcript is provided with either electronic version consulted.

D.C.R. [40], at para. 18.

At least on CanLII (where they are featured in colour) and Westlaw (where they appear to have been scanned in black and white); on Quicklaw, the entirepage on which they appear was ostensibly scanned for display.

While the sample is too small to draw any meaningful inference, we note these were all judgments written by male judges. Female judges are more descriptive than their male colleagues, and penned 75% of all “mentions of omission” decisions.

Elliott [49], at p. 34/88.

Grant [52], at para. 56.

Dhandhukia [48], at para. 4.

Kemp [38], at paras. 26, 31.

Swiftey [186], reports that Canadians are the biggest users of this evenly twisted turd emoji, now displayed with smiling eyes on most platforms. Stories differ as to the origin of the smiling poo meme: some trace it to a phonetic resemblance with the Japanese expression for “good luck,” (Healy [137]), others to Akira Toriyama’s Dr Slump manga: Schwartzberglong [160].

For instance, “

U+1F624 Face With Look of Triumph” is “spoken” by Apple iOs 11.3’s accessibility features as “Huffing With Anger Face” (this is further explained infra at §3.2in fine, Fig. 14).

U+1F624 Face With Look of Triumph” is “spoken” by Apple iOs 11.3’s accessibility features as “Huffing With Anger Face” (this is further explained infra at §3.2in fine, Fig. 14).Twenty including cats and the sun:

Smiling Face With Smiling Eyes;

Smiling Face With Smiling Eyes;

Slightly Smiling Face;

Slightly Smiling Face;

Smiling Face With Halo;

Smiling Face With Halo;

Grinning Face With Smiling Eyes;

Grinning Face With Smiling Eyes;

Beaming Face With Smiling Eyes;

Beaming Face With Smiling Eyes;

Smiling Face With Sunglasses;

Smiling Face With Sunglasses;

Smiling Face;

Smiling Face;

Grinning Face With Big Eyes;

Grinning Face With Big Eyes;

Kissing Face With Smiling Eyes;

Kissing Face With Smiling Eyes;

Smiling Face With Horns;

Smiling Face With Horns;

Grinning Squinting Face;

Grinning Squinting Face;

Face With Hand Over Mouth;

Face With Hand Over Mouth;

Smiling Face With Heart-Eyes;

Smiling Face With Heart-Eyes;

Grinning Face With Sweat;

Grinning Face With Sweat;

Smiling Face With 3 Hearts;

Smiling Face With 3 Hearts;

Cat Face With Wry Smile;

Cat Face With Wry Smile;

Grinning Cat Face With Smiling Eyes;

Grinning Cat Face With Smiling Eyes;

Grinning Cat Face;

Grinning Cat Face;

Smiling Cat Face With Heart Eyes;

Smiling Cat Face With Heart Eyes;

Sun With Face.

Sun With Face.Parsons [64], at para. 21.

Baker [4], at para. 11.

G.L. [51], at para. 60.

Navarro [37], at para. 11.

Otokiti [62], at para. 10.

Pelletier [18], at para. 49, translation is ours. There original reads: “Ici, l’ensemble du clavardage permet d’inférer que l’accusé recherchait visiblement l’excitation d’une nouvelle rencontre. Sa façon d’interpréter chaque détail anodin que X écrit comme une allusion à connotation sexuelle est éloquente. Ne serait-ce que cette demande de photo faite par l’adolescent, accompagnée d’émoticônes desquels l’accusé infère qu’il parle d’une photo coquine.”

A prior question from a procedural point of view (evidence is admitted in the file first, then, maybe, quoted into the judgment), but an ulterior question, from the perspective of a researcher (who must first find emoji or emoticon quoting cases, then deduct how and why they were included).

Papadopoulos [63] [message partly edited out]; Butler [45] [messages of deceased third party]; D.D. [47] [doubts as to message authorship]; Hatcher [25] [doubts as to whether smileys sent by child or “directed” by one parent]; N.W. [60], at para. 52 [on text messages generally]; see also, in Queensland (Australia), Re Nichol [76] where the issue was whether an unsent SMS (containing an emoji) was the deceased last will.

Therrien [14], at paras. 154–155.

Ulbricht [80], transcript of hearing, at pp. 286–287.

Tresierra [67], at para. 36: “Chat logs were also retrieved from Mr. Tresierra’s hard drive through the use of Encase keyword searches and the specialized software Yahoo Messenger Archive Decoder. Chat logs are abbreviated text messages between screen users. Emoticons (symbols with faces displaying an emotion) may be attached to the text. Chat logs are conducted in real time and are sometimes described as instant messaging.”

England [21], at p. 3/7: “Like verbal conversation, text messages are often replete with informalities, texting abbreviations (e.g. “LOL”) or emoticons and other similar social conventions.”

Couillard (Re) [16], at para. 17 stating that hearts and smiley faces (“bon[s]hommes sourire”) are so common especially among the youth (“très usitées de nos jours, particulièrement chez les jeunes”) that they do not amount to marks that can identify a voter on a ballot.

N.W. [60], at para. 52; See also Baglow [3], at paras. 100–101, where the court summarized an expert’s testimony to that effect: “Further computer mediated communication is also characterized by its lack of punctuation and use of “emoticons” to denote feelings and moods. Many linguistic conventions and styles on BBSs, chat rooms, et cetera, are derivative of early computer hacker language. They are common expressions, phrases and styles used specifically on Internet-based sites and platforms, including those frequented by online political actors. […] the lack of non-verbal cues (for example facial expressions that might indicate sarcasm or joking) tend to exacerbate debates over the meaning and intent of specific phrases and words. Misinterpretations are frequent.”

Marselje [33], at paras. 14–15.

Saussure [103], at p. 100.

Jakobson [100], at p. 115.

Century 21 [12], at para. 44–47 [emojis in a real-estate agent’s messages “belies [a] generally positive working relationship”]: Kinark [28], at p. 20/22 [“the objective evidence [including smiley faces] informing his relationship with Mr. Sutch militates against his view that their relationship, from the beginning of their working together, was one of animosity”].

Supra n. 46.

See Bedzow-Weisleder [6], at para. 14.

On intensity markers generally, see Romero [116].

The “A-Ok” gesture is culturally hazardous, as it may also be used for “zero” or a vulgar insult: Gesteland [99], at p. 88.

Danesi [97], at p. 87.

Danesi [97], at pp. 21, 59.

See M.B. [56], at para. 6.

Maughan (Sup. Ct) [34], at para. 32.

Maughan (Sup. Ct) [35], at para. 405.

TET-73196-16 [73].

See M.B. [56], at para. 6.

Dix [19], at para. 50.

See e.g., Wilson [96].

Danesi [97], at p. 39.

And perhaps on the adage that a picture is worth a thousand words: see Benenson (dir.), EmojiDick or,

[the Whale], by Herman Melville [192]; Hale, ‘Wonderland Emoji Poster [194]; Bing, “Book from the Ground” [193]; see generally: “Narratives In Emoji” [187]; see also “Tweeting case law as emoji (badly),” [188].

[the Whale], by Herman Melville [192]; Hale, ‘Wonderland Emoji Poster [194]; Bing, “Book from the Ground” [193]; see generally: “Narratives In Emoji” [187]; see also “Tweeting case law as emoji (badly),” [188].The Ouch Team [166].

Godlewski [135].

Moore [153].

Unicode Consortium, “Emoji and Pictographs” [176], itself notes, somewhat lackadaisically that “any pictorial representation of a [given code point], whether a line drawing, gray scale, or colored image (possibly animated) is considered an acceptable rendition for the given emoji. However, a design that is too different from other vendors’ representations may cause interoperability problems,” referring to its more detailed technical guidelines, Unicode Consortium, “UTS #51” [177].

Burge, “Burger” [123].

Burge, “Convergence?” [124].

At least one Spanish tribunal [77], has specifically cautioned attorneys on this topic: “la prueba de una comunicación bidireccional mediante cualquiera de los múltiples sistemas de mensajería instantánea debe ser abordada con todas las cautelas.”

Kirley and McMahon [91], at p. 24.

Both flags feature a white cross on a blue shield, with four identical ornaments, Martinican pit viper in one case, fleur-de-lys in the other. See online petition to add a Quebec flag to the Unicode’s next emoji release.

See supra n. 45.

On how new emojis contribute to “normalization” as an instrument of power, see Béjot [107], at pp. 53 ff.

For a related issue, see: Goldman, 2017 [88], at p. 15.

On emoji dictionaries, see Goldman, 2017 [88], at p. 18, noting that, despite their authors’ efforts or enthusiasm, Emojipedia; or The Emoji Dictionary entries are variable in quality. On text-to-speech, see supra, n. 86. On how this may contradict the inherent speed of e-communications, see: N.W. [60], at para. 52. On whether names are “conventional” or “natural,” see Plato’s Cratylus.

Oaks [155].

Moore [153].

Logan [146].

Corbett [130].

Danesi [97].

Barbieri et al. [106], p. 532.

Japanese post offices are rather marked “〒,” and the Unicode provides for a Japan-specific emoji: U+1F3E3.

See Oliver [156].

New York Public Hospitals, advertising campaign (April 2017), online.

For a summary, see: Miller [151].

Which is almost surprising considering their prevalence in the cases examined (see supra §1.2).

Varley [167].

Masemann [148]; see also the r/trees reddit thread.

Frisbee [50], at paras. 108–114.

Yeo [68], at para. 16.

Ambrose [42], at paras. 61–72.

Tatman [165].

Steinmetz [162], reporting unpublished research by Tyler Schnoebelen.

Steinmetz [162].

Mir [59], at para. 98.

Dresner and Herring [111].

Copeland [129].

Daft and Lengel [109].

Re Nichol [76].

Dahan [74].

Case Law

Canadian Cases

Amalgamated Transit Union, Local 113 v Toronto Transit Commission (Use of Social Media Grievance), [2016] O.L.A.A. No. 267.

Authorization (s. 43) 02-02; Insurance Corp. of British Columbia, [2002] B.C.I.P.C.D. No. 57.

Baglow v Smith, 2015 ONSC 1175.

Baker v Twiggs Coffee Roasters, 2014 HRTO 460.

Bédirian v Canada (Justice), 2002 PSSRB 89 .

Bedzow-Weisleder v Weisleder, 2018 ONSC 1969.

Ben-Tzvi v Ben-Tzvi, 2006 CanLII 25256 (ON SC).

C.V. et Responsable du CIUSSS A, 2015 CanLII 48507 (TAQ).

C.V. et Responsable du CSSS A, 2016 CanLII 33821 (TAQ).

Canada (Canadian Human Rights Commission) v Winnicki, 2006 FC 873.

Casimir c R., 2009 QCCA 1720.

Century 21 Dome Realty Inc. v Brittner, 2018 SKPC 24.

CISS-FM re Big Bag of Cash Contest, 2016 CBSC 9 .

Commissaire à la déontologie policière c Therrien, 2018 QCCDP 6.

Couche-Tard inc. c Abitbol, 2012 QCCS 4194.

Couillard (Re), 2011 QCCS 2618.

Crêpe It Up! v Hamilton, 2014 ONSC 6721.

Directrice des poursuites criminelles et pénales c Pelletier, 2016 QCCQ 9301.

Dix v The Twenty Theatre Company, 2017 HRTO 394.

DN Developments Ltd (Darren’s Homes) v Turner, 2014 ABQB 52.

England v Saunders-Todd, 2015 NSSM 61.

Garderie Les Frimousses du Fort inc. c École de musique Guylaine Messier inc., 1997 CanLII 8072 (QC CS) .

Group of Employees of Window City Industries Inc v United Brotherhood of Retail, Food, Industrial and Service Trades International Union, 2013 CanLII 76422 (ON LRB).

Hamilton v Crêpe it Up!, 2012 HRTO 1941.

Hatcher v Golding, 2017 ONSC 785.

Johnson (Re), 2016 LSBC 20.

K.C. et Compagnie A, 2015 QCCSST 184.

Kinark Child & Family Services Syl Apps Youth Centre v Ontario Public Service Employees Union, Local 213, 2012 CanLII 97669 (ON LA).

L’Association des policiers(ères) de Sherbrooke c Sherbrooke (Ville), 2017 CanLII 66054 (SAT).

Lachance c 9053-3704 Québec inc. (Garderie Frimousse), 2006 QCCQ 3889.

Law Society of Upper Canada v Forget, 2013 ONLSHP 158.

M. E. v Canada Employment Insurance Commission, 2015 CanLII 107643 (SST).

Marselje c Canada (Citoyenneté et Immigration), 2012 CanLII 99482 (SA CISR).

Maughan v UBC, 2008 BCSC 14 (conf. by 35 below).

Maughan v University of British Columbia, 2009 BCCA 447 (leave to appeal denied: 2010 CanLII 21652 (CSC).

Meyers v R., 2008 NLCA 13.

Navarro v Martinzez [sic], 2017 ONSC 2193.

Ontario College of Teachers v Kemp, 2017 ONOCT 68.

Picard et Chalifour Canada ltd, 2013 QCCRT 325.

R v D.C.R., 2017 BCPC 80.

R v JR, 2016 ABQB 414.

R. v Ambrose, 2015 ONCJ 813.

R. v B.F., 2018 ONSC 2240.

R. v Bishop, 2010 BCSC 1928.

R. v Butler, 2009 ABQB 97.

R. v C.C., 2016 ONSC 4524.

R. v D.D., 2015 ONSC 3667.

R. v Dhandhukia, 2007 CanLII 4312 (ON CS).

R. v Elliott, 2016 ONCJ 35.

R. v Frisbee, 1989 CanLII 2849 (BC CA).

R. v G.L., 2014 ONSC 3403.

R. v Grant, 2018 BCSC 413.

R. v Hamdan, 2017 BCSC 1770.

R. v Isaac, 2013 ONCJ 114.

R. v Khan, 2016 BCPC 168.

R. v M.B., 2016 BCCA 476.

R. v McCall, 2011 BCPC 143.

R. v McCall, 2011 BCPC 7 .

R. v Mir, 2012 ONCJ 594.

R. v N.W., 2018 ONSC 774.

R. v Ngai, 2013 ABPC 16.

R. v Otokiti, 2017 ONSC 5940.

R. v Papadopoulos, 2006 CanLII 49055 (ON SC).

R. v Parsons, 2015 CanLII 40726 (NL SC) (conf on verdict but reduced sentence by R. v Parsons, 2017 NLCA 64).

R. v Strickland, 2013 NLCA 65.

R. v Titchener, 2013 BCCA 64.

R. v Tresierra, 2006 BCSC 1013.

R. v Yeo, 2014 PESC 4.

R. v. Yanke, 2014 ABPC 88.

Slogoski v Mullan, 2015 BCSC 1810.

TET-73196-16 (Re), 2017 CanLII 49021 (ON LTB).

TST-85522-17 (Re), 2017 CanLII 142784 (ON LTB).

W.R.V. v S.L.V., 2007 NSSC 251.

Non-canadian cases

Dahan v Shacharoff, no 30823-08-16 (small claims, Herzliya District, Israel) case (original and English translation here) [Israel].

Ghanam v Does, 845 N.W.2d 128 (Mich. Ct. App. 2014) [United States].

Re Nichol; Nichol v Nichol [2017] QSC 220 (9 October 2017) [Australia].

R. c. Francisco (19 May 2015), sala de lo penal del Tribunal suprema, sentencia número 300/2015, ponente señor Marchena Gómez [Spain].

US v Cochran, 534 F.3d 631 (7th Circ. 2008), 632 [United States].

US v Shinn, 681 F.3d 924 (2012) [United States].

United States of America v Ross William Ulbricht, transcript of hearing before the honourable Katherine B. Forrest (13 January 2015), New York, NY, file no 14 Cr. 68 (KBF) [United States].

Warren & Peat [2017] FCCA 664 (23 February 2017) [Australia].

Wisconsin v Jacques, 332 Wis. 2d 804 (Wis. Ct. App. 2011) [United States].

LEGAL LITERATURE

An Act to establish the new Code of Civil Procedure, SQ 2014, c 1, explanatory notes.

Bailey, Jane et al. 2013. “Access to Justice for all: Towards an “Expansive Vision” of Justice and Technology” Windsor Journal of Access to Justice vol. 31, page 2.

Barnett Lidsky, Lyrissa and Linda Riedemann Norbut. 2018.“I

U: Considering the Context of Online Threats” California Law Review vol. 106, page 101.

U: Considering the Context of Online Threats” California Law Review vol. 106, page 101.Bich-Carrière, Laurence. 2018. “Protection juridique des émojis: :S ou ¯\_(ツ)_/¯?” in Barreau du Québec, Développements récents en droit de la propriété intellectuelle, Cowansville, QC: Yvon-Blais, page 305.

Franquet, Pablo. 16 June 2016. “Emoticonos: nuevos retos para la valoración de la prueba”, Litigio de Autor (Blog), online.

Goldman, Eric. 2017. “Surveying the Law of Emojis” Santa Clara University Legal Studies Research Paper 8-17.

Goldman, Eric. 2018. “Emojis and the Law” Santa Clara University Legal Studies Research Paper 6-18, forthcoming in the Washington Law Review.

Jutras, Daniel. 2009. “Culture et droit processuel: le cas du Québec” McGill Law Journal, vol. 54, page 273.

Kirley, Elizabeth and Marilyn McMahon. 2018. “The Emoji Factor: Humanizing the Emerging Law of Digital Speech” Tennessee Law Review, vol. 85, forthcoming.

Porter, Elizabeth G. 2014. “Taking Images Seriously” Columbia Law Review, vol. 114, page 1687.

Quebec, Ministry of Justice. 2006. Rapport d’évaluation de la Loi portant réforme du Code de procédure civile, Quebec: Official Printer.

Scall (Rachel). 2015. “Emoji as Language and Their Place outside American Copyright Law”, New York University Journal of Intellectual Property and Entertainment Law, vol. 5, page 381.

Tschanz, Peter T. 20 November 2015. “EMOJI-GOSH! How Emojis in Workplace Communications Can Spark A Lawsuit (Or Make It Harder To Defend One)”, The National Law Review, online.

Wilson, John O. 1980. A Book for Judges, Ottawa: PWGSC.

NON-LEGAL LITERATURE: Monographs

Danesi, Marcel. 2016. The Semiotics of Emoji: The Rise of Visual Language in the Age of the Internet, Bloomberg: New York.

Evans, Vyvyan. 2017. The Emoji Code: The Linguistics Behind Smiley Faces and Scaredy Cats, Picador: London.

Gesteland, Richard R., 2012. Cross-cultural Business Behavior: A Guide for Global Management, 5th ed., Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School Press.

Jakobson Roman. 1985. “Metalanguage as a Linguistic Problem” in Selected Writings, vol. 7 edited by Stephen Rudy, Berlin: Mouton, page 113.

Leber-Cook, Alice and Roy T. Cook. 2013. “Stigmatization, Multimodality and Metaphor – Comics in the Adult English as a Second Language Classroom” in Carrye Kay Syma and Robert G. Weiner (ed.), Graphic Novels and Comics in the Classroom: Essays on the Educational Power of Comics, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2.

McLuhan, Marshall. 1962. The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making Of Typographic Man, Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Saussure, Ferdinand de. 1971. Cours de linguistique générale, Paris: Payot.

Papers

Alshenqeeti, Hamza. 2016. “Are Emojis Creating a New or Old Visual Language for New Generations? A Socio-semiotic Study” Advances in Language and Literary Studies vol. 6, page 56, online.

Azuma, Junichi. 2012. “Graphic Emoticons as a Future Universal Symbolic Language” Approaches to Translation Studies vol. 16, page 56.

Barbieri, Francesco et al. 15-19 October 2016. “How Cosmopolitan Are Emojis?: Exploring Emojis Usage and Meaning over Different Languages with Distributional Semantics”, Proceeds of MM16 Conference from the Computing Machinery 2016, Amsterdam, 531, online.

Béjot, Virginie. November 2015. “Qu’est-ce que l’emoji veut ‘dire’?”, professional master thesis (media and communication), Paris-Sorbonne University, France.

Chen, Zhenpeng et al. 23-27 April 2018. “Through a Gender Lens: Learning Usage Patterns of Emojis from Large-Scale Android Users” in Proceedings of the World Wide Web Conference 2018 (Lyon), page 763.

Daft, Richard L. and Robert H. Lengel 1986. “Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design” Management Science vol. 32, page 554.

Derks, Daantja et al. 2008. “The Role of Emotion in Computer-Mediated Communication: A Review”, Computers in Human Behaviour vol. 24, page 766, online.

Dresner, Eli and Susan C. Herring. 2010. “Functions of the nonverbal in CMC: Emoticons and illocutionary force” Communication Theory vol. 20, page 249.

Kavanagh, Barry. 2012.“A Contrastive Analysis of American and Japanese Online Communication: A Study of U[nconventional] M[eans] of C[ommunication] Function and Usage in Popular Personal Weblogs” Journal of Aomori University of Health and Welfare vol. 13, no. 1, page 13, enhanced and updated: 25 March 2015.

Kingsbury, Maria. 2015. “How to Smile When They Can’t See Your Face: Rhetorical Listening Strategies for IM SMS Reference” International Journal of Digital Library Systems vol. 5, no. 1, page 31.

Kralj Novak, Petra et al. 2015. “Sentiment of Emojis” PLOSone, vol. 10, page 1.

Miller, Hannah et al. 17-20 May 2017 “‘Blissfully happy’ or ‘ready to fight’: Varying interpretations of emoji”, in Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Web and Social Media ICWSM 2016 (Cologne), page 259.

Romero, Clara.2007. “Pour une définition générale de l’intensité dans le langage” Travaux de linguistique vol. 54, no. 1, page 57.

Schneebeli, Célia. November 2017. “The interplay of emoji, emoticons, and verbal modalities in C[om-puter-]M[ediated] C[communications]: A case study of youtube comments” in Proceedings of the Visualizing (in) the New Media Conference (Neuchâtel).

Wiseman, Sarah and Sandy JJ Gould. 21-26 April 2018. “Repurposing Emoji for Personalised Communication: Why

means ‘I love you’” in Proceedings o the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems CHI 2018, Montreal, document no 152, online.

means ‘I love you’” in Proceedings o the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems CHI 2018, Montreal, document no 152, online.Wolf, Alecia. 200. “Emotional Expression Online: Gender Differences in Emoticon Use” Cyberpsychology & Behaviour, vol. 3, no. 5, page 1, online.

Yuki, Masaki, et al. 2007. “Are The Windows to the Soul the Same in the East and West?” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, page 43.

Newspapers, magazines and blogs

Abad-Santos, Alexander and Allie Jones. 26 March 2014. “The Five Non-Negotiable Best Emojis in the Land”, The Atlantic, online.

Bosker, Bianca. 27 June 2014. “How Emojis Get Lost in Translation”, The Huffington Post, online.

Burge, Jeremy. 28 November 2017. “Google Fixes Emoji Burger”, Emojipedia Blog, online.

Burge, Jeremy. 13 February 2018. “2018: The Year of Emoji Convergence?”, Emoijipedia Blog, online.

Burge, Jeremy. 4 June 2018. “Apple Unveils Memoji”, Emojipedia Blog, online.

Cole, Kathryn. 28 February 2018. “Texter Beware: Emojis As Evidence”, All About eDiscovery, online.

Collister, Lauren. 6 April 2015. “Emoticons and symbols aren’t ruining language – they’re revolutionizing it”, The Conversation, online.

Connor Martin, Katherine. “New word notes” (December 2013), online.

Copeland, Michael V. “Texting isn’t Writing; it’s Fingered Speech,” (1 March 2013), Wired, online.

Corbett, Philip B. 25 September 2008. “Begging the Question, Again”, After the Deadline Blog, New York Times, online.

DeFabio, Cara Rose. 1 May 2015. “Instagram Hashtags Could Be The Best Guide To Emoji Meaning We’ve Ever Had”, Fusion, online.

Dipshan, Rhys. 26 February 2018. “E-Discovery Can Tame Emojis, But Can’t Outpace Them”, LegalTech News, online.

Fahlman, Scott E. 2001. “Smiley Lore :-)” Carnegie Mellon University, online .

Fahlman, Scott E. 9 September 1982. “Original Bboard [sic] Thread in which :-) was proposed”, Carnegie Mellon University, online.

Godlewski, Nina. 7 March 2018. “Jazz Hands or Hugging Emoji? Here’s What Elon Musk Thinks”, Newsweek, online.

Goodman, Stacy. 23 November 2016. “And the Most Enchanting Emoji on Instagram is…”, Curalate, online.

Healy, Claire Marie. 12 May 2015. “What does the stinky poop emoji really mean?”, Dazed, online.

Hern, Alex. 6 February 2016. “Don’t know the difference between emoji and emoticon? Let me explain” The Guardian, online.

Hess, Amanda. 21 June 2016. “Hands Off My Smiley Face: Emoji Become Corporate Tools”, New York Times, online.

Hess, Amanda. 3 April 2015. “Move Over, Banana: How the eggplant became the most phallic food”, Slate.fr, online.

Instagram Engineering. 30 April 2015. “Emojineering Pt 1: Machine Learning for Emoji Trends”, online.

Johnson, Paddy. 26 February 2018. “Emoji Domains Are the Future (Maybe)”, Gizmodo, online.

Kaser, Rachel. 19 May 2017. “Judge rules emoji are proof of intent”, The Next Web, online.

Lam, Bourree. 15 May 2015. “Why Emoji Are Suddenly Acceptable at Work”, The Atlantic, online.

Lamonth, Judith. 14 September 2017. “Emerging content formats challenge e-discovery”, KMWorld Magazine, online.

Logan, Megan. 21 May 2015. “We’re All Using These Emoji Wrong”, Wired, online.

Manilève, Vincent. 31 July 2015. “Ne communiquer qu’avec des emojis est horrible (mais pas impossible)”, Slate.fr, online.

Masemann, Alison et al. 22 March 2018. “Emoji evidence is causing confused faces in courtrooms”, CBC Radio (transcript), online.

McPherson, Fiona. 15 August 2013. “Can ‘literally’ mean ‘figuratively’?”, Oxford English Dictionary Blog, online.

Merriam-Webster, “Usage notes: Did We Change the Definition of ‘Literally’?”, Merriam-Webster Dictionary, online.

Miller, Mark J. 1 December 2016. “Durex Crowns Umbrella Its Safe Sex #CondomEmoji on World AIDS Day”, Brandchannel, online.

Mlot, Stephanie. 23 May 2017, “In Israel, Squirrel, Comet Emoji Signal Intent to Rent”, Geek.com, online.

Moore, Catherine A. 26 May 2017. “Emoji as Visual Literacy”, Medium, online.

Nakano, Mamiko. 15 March 2015. “Why and how I created emoji: Interview with Shigetaka Kurita”, translation by Mitsuyo Inaba Lee, Ignition, archived in the Web.

Oaks, Rachel. 6 August 2017. “Are Emojis Really the Universal Language of the Internet?”, HighSpeed Internet.com, online.

Oliver, Laura. 28 December 2016. “A Brief History Of Food Emoji: Why You Won’t Find Hummus On Your Phone”, Food For Thought Blog, NPR, online.

Oxford Living English Dictionary. “Is Emoji a Type of Language?”, online.

Oxford Living English Dictionary. 16 November 2015. “Word of the Year 2015”, online.

Rhodes, Margaret. 8 April 2016. “Apple’s New Squirt Gun Emoji Hides a Big Political Statement”, Wired, online.

Schwartzberglong, Lauren. 18 November 2014. “The Oral History Of The Poop Emoji (Or, How Google Brought Poop To America)”, FastCompany, online.

Sremack, Joe. 8 February 2016. “Why Emojis Matter in E-Discovery”, Today’s General Counsel, online.

Steinmetz, Katy. 17 July 2014. “Here Are Rules of Using Emoji You Didn’t Know You Were Following”, Time, online.

Sternberg, Adam. 16 November 2014. “So you’re speaking emoji”, New York Magazine, online .

Stockton, Nick. 24 June 2015. “Emoji—Trendy Slang or a Whole New Language?”, Wired, online.

Tatman, Rachael. 7 December 2017. “Do emojis have their own syntax?”, Making Noise and Hearing Things, online.

The Ouch Team. 24 October 2015. “How do blind people see emojis?”, podcast, BBC News (blog), online.

Varley, Ciaran. “BBC Three investigation finds kids dealing drugs on social media” (14 July 2017), BBC 4, online.

Working Documents

Commission générale de terminologie et de néologie. 2 April 1999. “Vocabulaire de l’informatique et de l’internet: liste des termes, expressions et définitions adoptés”, (16 March 1999), JORF no. 78, page 3905.

Druide Informatique. June 2005. “Donner un visage français aux smileys”, bulletin Enquête linguistique, online.

Interoperability Working Group. “Definition”, AFUL, online.

Office québécois de la langue française, Banque de terminologie du Québec, s.v. “smiley/binette” (1995), online, “émoticône” (2016) online and “emoticon/émoticône” (2018), online.

Unicode Consortium. 23 September 2015. “Background: Emoji Glyph/Annotation Recommendations”, Public Review Issue # 294, online.

Unicode Consortium. 18 November 2015 (last update). “Unicode® History Corner”, online.

Unicode Consortium. 22 June 2017 (last update). “About the Unicode® Standard”, online.

Unicode Consortium. 26 June 2017 (last update). “Basic Questions”, online.

Unicode Consortium. 9 March 2018 (last update). “Emoji and Pictographs”, online.

Unicode Consortium. 21 May 2018. “Unicode® Technical Standard #51”, online.

Press Releases and commercial reports

Apple. 1 August 2016. “Apple adds more gender diverse emoji in iOS 10”, Apple, online.

Apple. 6 November 2017. “Differential Privacy”, online.

Apple. 29 March 2018. “Use Animoji on your iPhone X”, online.

Boxer Analytics. 29 September 2016, 12:18. “10 Things Every Attorney Should Know about Emojis. #ediscovery #emoji #legaltech”, Twitter, online.

Brandwatch, Emoji Report 2018, online.

DrEd.com, “Sexually Suggestive Emojis.” December 2015. online.

Microsoft. 25 April 2018, 18:27. “We are in the process of evolving”, Twitter, online.

Samsung. 31 May 2018. “AR Moji: Turn your selfie into an emoji and watch your messaging come alive”, online.

Swiftkey, Emoji Report (2015), online.

Social media

“Narratives In Emoji”, Tumblr, online.

“Tweeting case law as emoji (badly)”, Twitter account (since August 2016), online.

EmojiTracker.com, Realtime emoji use on Twitter, online (accessed on 30 May 2018).

FakeUnicode. 28 July 2017. Twitter, online.

WorldEmojiDay (17 July 2017 16:11), Facebook post, online .

Literary works

Benenson, Fred (dir.), July 2010. EmojiDick or,

[the Whale], by Herman Melville, online.

[the Whale], by Herman Melville, online.Bing, Xu. 2014. “Book from the Ground”, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hale, Joe. January 2015. ‘Wonderland Emoji Poster, online.

Acknowledgements

© 2018 Laurence Bich-Carrière; BCL, LLB McGill (2008); LLM Cantab (2009), member of the Quebec (2009) and Ontario (2011) Bars. The author is currently a lawyer at Lavery, de Billy llp and a research scholar at the Paul-A. Crépeau Centre for Private and Comparative Law. This paper was presented as a workshop at the 12th Summer Institute of Jurilinguistics (Montreal, 15 June 2018), organized by the Crépeau Centre at the Faculty of Law of McGill University, and is part of wider research she conducts on emojis and the law. Unless otherwise indicated, the search is up-to-date and hyperlinks are functional as at 1 June 2018, and all underlining is the author’s, who wishes to thank all those who patiently bore with her emoji-testing texting as well as Mr. François Beaudry and Ms. Victoria Cohene for his dynamic and her patient comments on an earlier version of this conference paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bich-Carrière, L. Say it with [A Smiling Face with Smiling Eyes]: Judicial Use and Legal Challenges with Emoji Interpretation in Canada. Int J Semiot Law 32, 283–319 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-018-9594-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-018-9594-5

U+1F624 Face With Look of Triumph” is “spoken” by Apple iOs 11.3’s accessibility features as “Huffing With Anger Face” (this is further explained infra at §

U+1F624 Face With Look of Triumph” is “spoken” by Apple iOs 11.3’s accessibility features as “Huffing With Anger Face” (this is further explained infra at § Smiling Face With Smiling Eyes;

Smiling Face With Smiling Eyes;

Slightly Smiling Face;

Slightly Smiling Face;

Smiling Face With Halo;

Smiling Face With Halo;

Grinning Face With Smiling Eyes;

Grinning Face With Smiling Eyes;

Beaming Face With Smiling Eyes;

Beaming Face With Smiling Eyes;

Smiling Face With Sunglasses;

Smiling Face With Sunglasses;

Smiling Face;

Smiling Face;

Grinning Face With Big Eyes;

Grinning Face With Big Eyes;

Kissing Face With Smiling Eyes;

Kissing Face With Smiling Eyes;

Smiling Face With Horns;

Smiling Face With Horns;

Grinning Squinting Face;

Grinning Squinting Face;

Face With Hand Over Mouth;

Face With Hand Over Mouth;

Smiling Face With Heart-Eyes;

Smiling Face With Heart-Eyes;

Grinning Face With Sweat;

Grinning Face With Sweat;

Smiling Face With 3 Hearts;

Smiling Face With 3 Hearts;

Cat Face With Wry Smile;

Cat Face With Wry Smile;

Grinning Cat Face With Smiling Eyes;

Grinning Cat Face With Smiling Eyes;

Grinning Cat Face;

Grinning Cat Face;

Smiling Cat Face With Heart Eyes;

Smiling Cat Face With Heart Eyes;

Sun With Face.

Sun With Face. [the Whale], by Herman Melville [

[the Whale], by Herman Melville [ U: Considering the Context of Online Threats” California Law Review vol. 106, page 101.

U: Considering the Context of Online Threats” California Law Review vol. 106, page 101. means ‘I love you’” in Proceedings o the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems CHI 2018, Montreal, document no 152, online.

means ‘I love you’” in Proceedings o the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems CHI 2018, Montreal, document no 152, online.