Abstract

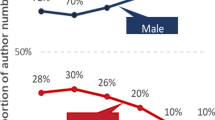

Prior literature suggests that the publication rates of female academics are less than the publication rates of male academics. This holds true in nearly every academic field and in every region, but these differences are declining over time. Women also are underrepresented in the first-author byline position. This study examines academics working and publishing in different business disciplines, and it addresses three distinct topics. It investigates (1) whether there is a relationship between the gender of first-listed authors of articles published and the ranking of journals; (2) it considers the relationship between the gender of the first-listed author of articles and different disciplines within business, specifically accounting, business technology, marketing, and organizational behavior; and (3) it evaluates how the publication rates of the two genders of first authors change over a 20-year period (1999–2018) for different disciplines. This research demonstrates that the gender gap is closing for female first authors in business academics, but that parity has not yet been reached. Women continue to be published less frequently in first-author positions in journals across all business disciplines studied, but especially in the higher-ranked journals, albeit with significant differences between business academic disciplines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In fields where the convention is to order alphabetically, the first author position is a simple random sample. In fields where the norm is to order by author contribution, women are likely under-represented in the first author position simply because there are fewer women professors of all ranks with lower percentages as rank increases (McChesney and Bichsel 2020). However, given that these ordering conventions have not changed with time for any of the disciplines studied (Joanis and Patil 2021), findings based upon year over year changes are unaffected by this underrepresentation.

Alternative methodologies to determine “Top” and “Other” journals were assessed, including assessing the “Top” and “Other” journals of today and assessing them retrospectively back in time—the issue with this methodology (and all others assessed) is that for the business disciplines studied, many of the journals of today did not exist 20 years ago, and many of the journals of 20 years ago do not exist today.

If an article is published in a top journal, it would have a value of 1 for the HighRank variable and a value of 0 for the LowRank variable. Similarly, if an article is published in a journal not considered a top journal, it would have a value of 0 for the HighRank variable and a value of 1 for the LowRank variable. In no cases would both HighRank and LowRank be included as variables in the same regression since this would violate regression assumptions.

The rationale for using the year 2011 as the division year between NewArticle and OldArticle is discussed in “Hypothesis 4” section. below.

All of the analyses conducted in this research have categorical independent variables with the dependent variable measured in percent. This leads to a relatively simple interpretation of all regression coefficients. When considered in percentage terms, the regression coefficients can be viewed as the percentage point increase in the percentage of female first authors predicted for the variable being assessed. In this case, using Analysis 1 of Table 3, the first author is predicted to be female 23.78% of the time for high ranked journals. Because the coefficient for low ranked journals is 0.0370, this coefficient value can be viewed in percentage terms (3.70%) and added to 23.78% for a prediction of female first authorship position of 27.48%. This methodology is applied throughout this manuscript.

References

Abramo, G., Cicero, T., & D’Angelo, C. (2015). Should the research performance of scientists be distinguished by gender? Journal of Informetrics, 9(1), 25–38.

Abramo, G., D’Angelo, C. A., & Caprasecca, A. (2009). The contribution of star scientists to sex differences in research productivity. Scientometrics, 81(1), 137–156.

Alderman, J. (2021). Women in the smart machine age: Addressing emerging risks of an increased gender gap in the accounting profession. Journal of Accounting Education, 55, 100715.

Amoroso, S., & Audretsch, D. (2020). The role of gender in linking external sources of knowledge and R&D intensity. Economics of Innovation and New Technology.

Astegiano, J., Sebastián-González, E., & Castanho, C. (2019). Unravelling the gender productivity gap in science: A meta-analytical review. Royal Society Open Science, 6(6), 181566.

Astin, H., & Davis, D. (2019). Research productivity across the life and career cycles: Facilitators and barriers for women. In Scholarly writing & publishing. Routledge.

Baker, M. (2010). Career confidence and gendered expectations of academic promotion. Journal of Sociology, 46(3), 317–334.

Bhandari, M., Guyatt, G., Kulkarni, A., Devereaux, P., Leece, P., Bajammal, S., & Busse, J. (2014). Perceptions of authors’ contributions are influenced by both byline order and designation of corresponding author. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(9), 1049–1054.

Biehl, M., Kim, H., & Wade, M. (2006). Relationships among the academic business disciplines: A multi-method citation analysis. Omega, 34(4), 359–371.

Brooks, C., Fenton, E., & Walker, J. (2014). Gender and the evaluation of research. Research Policy, 43(6), 990–1001.

Casadevall, A., Semenza, G., Jackson, S., Tomaselli, G., & Ahima, R. (2019). Reducing bias: Accounting for the order of co–first authors. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 129(6), 2167–2168.

Chen, Y., Nixon, M., Gupta, A., & Hoshower, L. (2010). Research productivity of accounting faculty: An exploratory study. American Journal of Business Education, 3, 101–115.

Ciminello, F., & Eloy, J. (2014). Research productivity and gender disparities: A look at academic plastic surgery. Journal of Surgical Education, 71(4), 593–600.

Falagas, M., Pitsouni, E., Malietzis, G., & Pappas, G. (2008). Comparison of PubMed, scopus, web of science, and google scholar: Strengths and weaknesses. The FASEB Journal, 22(2), 338–342.

Forliano, C., De Bernardi, P., & Yahiaoui, D. (2021). Entrepreneurial universities: a bibliometric analysis within the business and management domains. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 165, 120522.

Ghosh, P., & Liu, Z. (2020). Coauthorship and the gender gap in top economics journal publications. Applied Economics Letters, 27(7), 580–590.

Gingras, Y., & Khelfaoui, M. (2018). Assessing the effect of the United States’“citation advantage” on other countries’ scientific impact as measured in the Web of Science (WoS) database. Scientometrics, 114(2), 517–532.

Ginther, D., & Kahn, S. (2021). Women in Academic Economics: Have We Made Progress?. In AEA Papers and Proceedings (Vol. 111, pp. 138–42).

Guerrero-Bote, V., & Moya-Anegón, F. (2012). A further step forward in measuring journals’ scientific prestige: The SJR2 indicator. Journal of Informetrics, 6(4), 674–688.

Hansen, J., & Wänke, M. (2009). Liking what’s familiar: The importance of unconscious familiarity in the mere-exposure effect. Social Cognition, 27(2), 161–182.

Hengel, E., & Moon, E. (2019). “Gender and Quality at Top Economic Journals.” Working paper: https://erinhengel.github.io/Gender-Quality/quality.pdf

Joanis, S., & Patil, V. (2021). Alphabetical ordering of author surnames in academic publishing: A detriment to teamwork. PLoS ONE, 16(5), 251–276.

Kogovšek, M., & Kogovšek, M. (2017). Academic seniority and research productivity exploring gender as a moderator. Quaestus, 10, 177–188.

König, C. (2019). How much is research in the top journals of industrial/organizational psychology dominated by authors from the US? Scientometrics, 120(3), 1147–1161.

Kou, M., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y., Chen, K., Guan, J., & Xia, S. (2020). Does gender structure influence R&D efficiency? A Regional Perspective. Scientometrics, 122(1), 477–501.

Lerchenmueller, M., & Sorenson, O. (2018). The gender gap in early career transitions in the life sciences. Research Policy, 47(6), 1007–1017.

Long, J. (1992). Measures of sex differences in scientific productivity. Social Forces, 71(1), 159–178.

Lundine, J., Bourgeault, I., Clark, J., Heidari, S., & Balabanova, D. (2018). The gendered system of academic publishing. The Lancet, 391(10132), 1754–1756.

Lutter, M., & Schröder, M. (2020). Is there a motherhood penalty in academia? The gendered effect of children on academic publications in German sociology. European Sociological Review, 36(3), 442–459.

Lynn, F., Noonan, M., Sauder, M., & Andersson, M. (2019). A rare case of gender parity in academia. Social Forces, 98(2), 518–547.

Maddi, A., & Gingras, Y. (2020). Gender diversity in research teams and citation impact in Economics and Management. arXiv, 2011.14823.

Mañana-Rodríguez, J. (2015). A critical review of SCImago Journal and country rank. Research Evaluation, 24(4), 343–354.

Maphalala, M., & Mpofu, N. (2017). Are we there yet? A literature study of the challenges of women academics in institutions of higher education. Gender and Behaviour, 15(2), 9216–9224.

Mathews, A., & Andersen, K. (2001). A gender gap in publishing? Women’s representation in edited political science books. Political Science & Politics, 34(1), 143–147.

McChesney, J., & Bichsel, J. (2020). The Aging of Tenure-Track Faculty in Higher Education: Implications for Succession and Diversity. College and University Professional Association for Human Resources.

Mittal, V., Feick, L., & Murshed, F. (2008). Publish and prosper: The financial impact of publishing by marketing faculty. Marketing Science, 27(3), 430–442.

Mongeon, P., & Paul-Hus, A. (2016). The journal coverage of web of science and scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics, 106(1), 213–228.

Nielsen, M. (2017). Gender and citation impact in management research. Journal of Informetrics, 11(4), 1213–1228.

O’Brien, K., & Hapgood, K. (2012). The academic jungle: Ecosystem modelling reveals why women are driven out of research. Oikos, 121(7), 999–1004.

Patil, V. (2014). Identification of influential marketing scholars and their institutions using social network analysis. Journal of Marketing Analytics, 2(4), 239–249.

Potter, H., Higgins, G., & Gabbidon, S. (2011). The influence of gender, race/ethnicity, and faculty perceptions on scholarly productivity in criminology/criminal justice. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 22(1), 84–101.

R Core Team (2019). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

Reed, D., Enders, F., Lindor, R., McClees, M., & Lindor, K. (2011). Gender differences in academic productivity and leadership appointments of physicians throughout academic careers. Academic Medicine, 86(1), 43–47.

Reisenberg, D., & Lundberg, G. (1990). The order of authorship: Who’s on first? JAMA, 14(264), 1857.

Santamaría, L., & Mihaljević, H. (2018). Comparison and benchmark of name-to-gender inference services. PeerJ Computer Science, 4, E156.

Sebo, P., Maisonneuve, H., & Fournier, J. P. (2020). Gender gap in research: A bibliometric study of published articles in primary health care and general internal medicine. Family Practice, 37(3), 325–331.

Süßenbacher, S., Amering, M., Gmeiner, A., & Schrank, B. (2017). Gender-gaps and glass ceilings: A survey of gender-specific publication trends in psychiatry between 1994 and 2014. European Psychiatry, 44, 90–95.

Symonds, M., Gemmell, N., Braisher, T., Gorringe, K., & Elga, M. (2006). Gender differences in publication output: Towards an unbiased metric of research performance. PLoS ONE, 1(1), 127–143.

Tennant, J. (2020). Web of science and scopus are not global databases of knowledge. European Science Editing, 46, e51987.

Thelwall, M., & Sud, P. (2020). Greater female first author citation advantages do not associate with reduced or reducing gender disparities in academia. Quantitative Science Studies, 1(3), 1283–1297.

Tougas, C., Valtanen, R., Bajwa, A., & Beck, J. (2020). Gender of presenters at orthopaedic meetings reflects gender diversity of society membership. Journal of Orthopaedics, 19, 212–217.

Van Dijk, D., Manor, O., & Carey, L. (2014). Publication metrics and success on the academic job market. Current Biology, 24(11), 516–517.

West, J., Jacquet, J., King, M., Correll, S., & Bergstrom, C. (2013). The role of gender in scholarly authorship. PloS one, 8(7), e66212.

Weisshaar, K. (2017). Publish and perish? An assessment of gender gaps in promotion to tenure in academia. Social Forces, 96(2), 529–560.

Wren, J., Kozak, K., Johnson, K., Deakyne, S., Schilling, L., & Dellavalle, R. (2007). The write position: A survey of perceived contributions to papers based on byline position and number of authors. EMBO Reports, 8(11), 988–991.

Zajonc, R. (2001). Mere exposure: A gateway to the subliminal. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10(6), 224–228.

Zhu, J., & Liu, W. (2020). A tale of two databases: The use of Web of Science and Scopus in academic papers. Scientometrics, 123(1), 321–335.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: STJ; Methodology: STJ and VHP; Formal analysis and investigation: STJ; Writing—original draft preparation: STJ; Writing—review and editing: STJ and VHP; Supervision: VHP.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Code availability

All R code is available upon request.

Data availability

All data is available upon request.

Appendix

Appendix

Certain analyses in this study rely on interaction variables including the age of a journal article as one of the multipliers in the interation, specifically the analyses associated with Hypothesis 4 (shown in Tables 5, 6, 7 and 8). One of the multipliers in these interaction variables is a categorical value of article age, and can either be NewArticle and OldArticle, with a 1 indicating membership (and a 0 otherwise). In the case of the analysis associated with Hypothesis 4, NewArticle was defined as those articles from 2012 and later, and OldArticle being those articles from 2011 and earlier. This division was determined by the year in which the Year variable went from significant to not significant in the analysis associated with Hypothesis 3 (see Table 4, Analysis 4). Although this division year was not determined arbitrarily, other division dates were investigated in order to determine if the results of the hypothesis testing for Hypothesis 4 were robust to changing the division date determining whether an article was considered a NewArticle or OldArticle. Since the sample period is an even number (20 years), there are two years closest to the midpoint of the sample year range (2008 and 2009). For the purpose of this robustness analysis, the same analyses performed in Tables 5, 6, 7 and 8 above were replicated with these two new division years, and the results were compared to the 2011 division year from the Hypothesis 4 analysis. For brevity, only Analysis 1 from each of the Tables 5, 6, 7 and 8 are shown in Tables 11, 12, 13 and 14 below.

As can be seen in each of the Tables 11, 12, 13 and 14 no conclusions would be changed based upon using 2008, 2009, or 2011 as the division year, since no coefficient signs change and no coefficients become significant that were formerly insignificant, with the opposite also being the case. Although not shown here, all years between 2007 and 2013 were assessed with consistent results. We conclude, therefore, that the Hypothesis 4 results are robust to the division year determining the difference between NewArticle and OldArticle.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Joanis, S.T., Patil, V.H. First-author gender differentials in business journal publishing: top journals versus the rest. Scientometrics 127, 733–761 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04235-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04235-z