Abstract

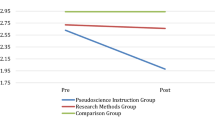

Critical thinking skills are often assessed via student beliefs in non-scientific ways of thinking, (e.g, pseudoscience). Courses aimed at reducing such beliefs have been studied in the STEM fields with the most successful focusing on skeptical thinking. However, critical thinking is not unique to the sciences; it is crucial in the humanities and to historical thinking and analysis. We investigated the effects of a history course on epistemically unwarranted beliefs in two class sections. Beliefs were measured pre- and post-semester. Beliefs declined for history students compared to a control class and the effect was strongest for the honors section. This study provides evidence that a humanities education engenders critical thinking. Further, there may be individual differences in ability or preparedness in developing such skills, suggesting different foci for critical thinking coursework.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Aarnio, K., & Lindeman, M. (2005). Paranormal beliefs, education, and thinking styles. Personality and Individual Differences, 39, 1227–1236.

Abrami, P. C., et al. (2008). Instructional interventions affecting critical thinking skills and dispositions: a stage 1 meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 78(4), 1102–1134.

Allchin, D. (2004). Pseudohistory and pseudoscience. Science & Education, 13, 179–195.

Arum, R., & Roksa, J. (2011). Academically adrift: limited learning on college campuses. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Barnett, S. M., & Ceci, S. J. (2002). When and where do we apply what we learn?: a taxonomy for far transfer. Psychological Bulletin, 128(4), 612–637. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.612.

Boudry, M. (2013). Loki’s wager and Laudan’s error: on genuine and territorial demarcation. In M. Pigliucci & M. Boudry (Eds.), Philosophy of pseudoscience: reconsidering the demarcation problem (pp. 79–100). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bridgstock, M. (2003). Paranormal beliefs among science students. Australasian Science, 24(4), 33–35.

Bunge, M. (2010). Knowledge: genuine and bogus. Science & Education, 20(5–6), 411–438.

Davies, M. (2013). Critical thinking and the disciplines reconsidered. Higher Education Research & Development, 32(4), 529–544.

DeRobertis, M. M., & Delaney, P. A. (1993). A survey of the attitudes of university students to astrology and astronomy. Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, 87(1), 34–50.

Diamond, J. (2005). Collapse: how societies choose to fail or succeed. New York: Penguin Group.

Dougherty, M. J. (2004). Educating believers: research demonstrates that courses in skepticism can effectively decrease belief in the paranormal. Skeptic, 10(4), 31–35.

Facione, P. A. (1990). Critical thinking: a statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction. Millbrae: The California Academic Press.

Feder, K. (1984). Irrationality and archaeology. American Antiquity, 49(3), 525–541.

Feder, K. (1995). Ten years after: surveying misconceptions about the human past. Cultural Resource Management, 18(3), 10–14.

Feder, K. (2010). Frauds, myths, and mysteries: science and pseudoscience in archaeology (7th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Fitzgerald, J., & Baird, V. A. (2011). Taking a step back: teaching critical thinking by distinguishing appropriate type of evidence. Political Science and Politics, 44(3), 619–624.

Franz, T. M., & Green, K. H. (2013). The impact of an interdisciplinary learning community course on pseudoscientific reasoning in first-year science students. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 13(5), 90–105.

Freidel, D. (2007). Betraying the Maya. Archaeology Magazine, 60(2), 36–41.

Goode, E. (2002). Education, scientific knowledge, and belief in the paranormal. Skeptical Inquirer, 26(1), 24–27.

Gray, T. (1985). Changing unsubstantiated belief: testing the ignorance hypothesis. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 17, 263–270.

Harrold, F. B., & Eve, R. A. (Eds.). (1987). Cult archaeology and creationism: understanding pseudoscientific beliefs about the past. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Holtorf, C. (2005). From Stonehenge to Las Vegas: archaeology as popular culture. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Johnson, M., & Pigliucci, M. (2004). Is knowledge of science associated with higher skepticism of pseudoscientific claims? The American Biology Teacher, 66(8), 536–548.

Kane, M. J., Core, T. J., & Hunt, R. R. (2010). Bias versus bias: harnessing hindsight to reveal paranormal belief change beyond demand characteristics. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 17(2), 206–212. doi:10.3758/PBR.17.2.206.

Karimi, F., & Sutton, J. (2014). Maryland mom kills two of her children during attempted exorcism. CNN. http://www.cnn.com/2014/01/19/justice/maryland-exorcism-deaths/. Accessed 20 Feb.

Lobato, E., Mendoza, J., Sims, V., & Chin, M. (2014). Examining the relationship between conspiracy theories, paranormal beliefs, and pseudoscience acceptance among a university population. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 28, 617–625.

Losh, S. C., & Nzekwe, B. (2011). Creatures in the classroom: preservice teacher beliefs about fantastic beasts, magic, extraterrestrials, evolution and creationism. Science & Education, 20, 473–489.

McAnany, P. A., & Negrón, T. G. (2009). Bellicose rulers and climatological peril? Retrofitting 21st century woes on 8th century Maya society. In In questioning collapse: human resilience, ecological vulnerability, and the aftermath of empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McAnany, P. A., & Yoffee, N. (Eds.) (2010). Questioning collapse: human resilience, ecological vulnerability, and the aftermath of empire. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Niu, L., Behar-Horenstein, L. S., & Garvan, C. W. (2013). Do instructional interventions influence college students’ critical thinking skills? A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 9, 114–128.

NSF. (2014). Chapter 7: Science and technology: public attitudes and understanding. In Science and Engineering Indicators 2014. National Science Foundation, 7–1–7-37.

Pascarella, E. T., Blaich, C., Martin, G. L., & Hanson, J. M. (2011). How robust are the findings of academically adrift? Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 43(3), 20–24.

Paul, R. (1995). Critical thinking: how to prepare students for a rapidly changing world. Rohnert Park: Foundation for Critical Thinking.

Pew (2013). Public’s knowledge of science and technology. Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C. (April). http://www.people-press.org/files/legacy-pdf/04-22-13%20Science%20knowledge%20Release.pdf. Accessed 23 Nov 2014.

Pyburn, A. (2006). The politics of collapse. Archaeologies, 2(1), 3–7.

Ren, A. C. (2006). Maya archaeology and the political and cultural identity of contemporary Maya in Guatemala. Archaeologies, 2(1), 8–19.

Rice, T. W. (2003). Believe it or not: religious and other paranormal beliefs in the United States. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 42, 95–106.

Ryan, T. J., Brown, J., Johnson, A., Sanburg, C., & Schildmeier, M. (2004). Science literacy and belief in the paranormal—an empirical test. Skeptic, 10(4), 12–13.

Sagan, C. (1996). The demon-haunted world: science as a candle in the dark. New York: Ballantine Books.

Smith, M. U., & Siegel, H. (2004). Knowing, believing, and understanding: what goals for science education? Science & Education, 13, 553–582.

Tobacyk, J. (2004). A revised paranormal belief scale. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 23, 94–98.

Turgut, H. (2011). The context of demarcation in nature of science teaching: the case of astrology. Science & Education, 20(5–6), 491–515.

Wesp, R., & Montgomery, K. (1998). Developing critical thinking through the study of paranormal phenomena. Teaching of Psychology, 25, 275–278.

Wood, M. J., Douglas, K. M., & Sutton, R. M. (2012). Dead and alive: beliefs in contradictory conspiracy theories. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(6), 767–773.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This research was approved by the North Carolina State University IRB and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest regarding this project.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Pew test of science knowledge

All radioactivity is man-made. Is this statement true or false?

Correct Answer: False

Electrons are smaller than atoms. Is this statement true or false?

Correct Answer: True

Lasers work by focusing sound waves. Is this statement true or false?

Correct Answer: False

The continents on which we live have been moving their location for millions of years and will continue to move in the future. Is this statement true or false?

Correct Answer: True

Which one of the following types of solar radiation does sunscreen protect the skin from?

Correct Answer: Ultraviolet

x-rays

infrared

microwaves

Does nanotechnology deal with things that are extremely...

Correct Answer: small

large

cold

hot

Which gas makes up most of the Earth’s atmosphere?

Correct Answer: Nitrogen

Hydrogen

Carbon Dioxide

Oxygen

What is the main function of red blood cells?

Correct Answer: Carry oxygen to all parts of the body

Help the blood to clot

Fight disease in the body

Which of these is a major concern about the overuse of antibiotics?

Correct Answer: It can lead to antibiotic-resistant bacteria

People will become addicted to antibiotics

Antibiotics are very expensive

Which is an example of a chemical reaction?

Correct Answer: Nails rusting

Water boiling

Sugar dissolving

Which is the better way to determine whether a new drug is effective in treating a disease? If a scientist has a group of 1000 volunteers with the disease to study, should she...

Correct Answer: Give the drug to half of them but not to the other half, and compare how many in each group get better

Give the drug to all of them and see how many get better

What gas do most scientists believe causes temperatures in the atmosphere to rise?

Correct Answer: Carbon dioxide

Helium

Radon

Hydrogen

Which natural resource is extracted in a process known as “fracking”?

Correct Answer: Natural gas

Coal

Diamonds

Silicon

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McLaughlin, A.C., McGill, A.E. Explicitly Teaching Critical Thinking Skills in a History Course. Sci & Educ 26, 93–105 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-017-9878-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-017-9878-2