Abstract

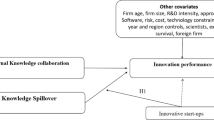

According to the Knowledge Spillover Theory of Entrepreneurship (KSTE), the majority of innovative start-ups take advantage of the knowledge originated in incumbent firms or universities. However, little is known on how innovative start-ups’ heterogeneous originating contexts affect their performance differences at founding. To address this gap, we complement the KSTE with the resource-based view of the firm to hypothesize how the origin of innovative start-ups affects their initial technological knowledge and, in turn, performance at founding. We test the model using a sample of 338 innovative start-ups. Our results show that innovative start-ups that originated from university report a performance advantage since, right from their origin, their technological knowledge displays a broad scope and higher levels of newness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

More specifically, the innovative character of start-ups is identified by at least one of the following criteria: (i) at least 15% of the company’s expenses can be attributed to R&D activities, (ii) at least 1/3 of the total workforce are doctoral students, PhDs, or researchers, or, alternatively, 2/3 of the total workforce have a Master’s degree, and/or (iii) the start-up is the holder, depositary, or licensee of a registered patent (industrial property), or the owner and author of a registered software.

These include, among others, the possibility to remunerate workers and consultants through stock options, and the possibility to raise equity through crowdfunding portals, robust tax incentives for investors, and access to public guarantees on bank loans.

By Bureau van Dijk.

References

Acs, Z., Braunerhjelm, P., Audretsch, D., & Carlsson, B. (2009). The knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 32(1), 15–30.

Acs, Z. J., Audretsch, D. B., & Lehmann, E. E. (2013). The knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 41(4), 757–774.

Agarwal, R., & Shah, S. K. (2014). Knowledge sources of entrepreneurship: firm formation by academic, user and employee innovators. Research Policy, 43(7), 1109–1133.

Agarwal, R., Echambadi, R., Franco, A. M., & Sarkar, M. B. (2004). Knowledge transfer through inheritance: spin-out generation, development, and survival. Academy of Management Journal, 47(4), 501–522.

Anokhin, S., & Wincent, J. (2014). Technological arbitrage opportunities and interindustry differences in entry rates. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(3), 437–452.

Audretsch, D. B., & Belitski, M. (2013). The missing pillar: the creativity theory of knowledge spillover entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 41(4), 819–836.

Audretsch, D. B., & Keilbach, M. (2007). The theory of knowledge spillover entrepreneurship. Journal of Management Studies, 44(7), 1242–1254.

Autio, E., Kenney, M., Mustar, P., Siegel, D., & Wright, M. (2014). Entrepreneurial innovation: the importance of context. Research Policy, 43(7), 1097–1108.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173.

Belitski, M., Aginskaja, A., & Marozau, R. (2019). Commercializing university research in transition economies: technology transfer offices or direct industrial funding? Research Policy, 48(3), 601–615.

Bhide, A. (2000). The origin and evolution of new businesses. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bradley, S. R., Hayter, C. S., & Link, A. N. (2013). Models and methods of university technology transfer. Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship, 9(6), 571–650.

Braunerhjelm, P., Ding, D., & Thulin, P. (2018). The knowledge spillover theory of intrapreneurship. Small Business Economics, 51(1), 1–30.

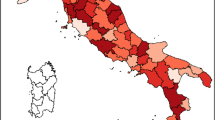

Cavallo, A., Ghezzi, A., Colombelli, A., & Casali, G. L. (2018). Agglomeration dynamics of innovative start-ups in Italy beyond the industrial district era. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-018-0521-8

Chatterji, A. K. (2009). Spawned with a silver spoon? Entrepreneurial performance and innovation in the medical device industry. Strategic Management Journal, 30(2), 185–206.

Clarysse, B., Wright, M., & Van de Velde, E. (2011). Entrepreneurial origin, technological knowledge, and the growth of spin-off companies. Journal of Management Studies, 48(6), 1420–1442.

Colombelli, A. (2016). The impact of local knowledge bases on the creation of innovative start-ups in Italy. Small Business Economics, 47(2), 383–396.

Colombelli, A., & Quatraro, F. (2018). New firm formation and regional knowledge production modes: Italian evidence. Research Policy, 47(1), 139–157.

Colombelli, A., Krafft, J., & Vivarelli, M. (2016). To be born is not enough: the key role of innovative start-ups. Small Business Economics, 47(2), 277–291.

Colombo, M. G., & Piva, E. (2012). Firms’ genetic characteristics and competence-enlarging strategies: a comparison between academic and non-academic high-tech start-ups. Research Policy, 41(1), 79–92.

Colombo, M., Mustar, P., & Wright, M. (2010). Dynamics of science-based entrepreneurship. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 35(1), 1–15.

Davidsson, P., Steffens, P., & Fitzsimmons, J. (2009). Growing profitable or growing from profits: putting the horse in front of the cart? Journal of Business Venturing, 24(4), 388–406.

De Carolis, D. M., Litzky, B. E., & Eddleston, K. A. (2009). Why networks enhance the progress of new venture creation: the influence of social capital and cognition. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(2), 527–545.

Feldman, M., Feller, I., Bercovitz, J., & Burton, R. (2002). Equity and the technology transfer strategies of American research universities. Management Science, 48(1), 105–121.

Fini, R., Rasmussen, E., Siegel, D., & Wiklund, J. (2018). Rethinking the commercialization of public science: from entrepreneurial outcomes to societal impacts. Academy of Management Perspectives, 32(1), 4–20.

Franklin, S. J., Wright, M., & Lockett, A. (2001). Academic and surrogate entrepreneurs in university spin-out companies. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 26(1–2), 127–141.

Frederiksen, L., Wennberg, K., & Balachandran, C. (2016). Mobility and entrepreneurship: evaluating the scope of knowledge–based theories of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(2), 359–380.

Fryges, H., & Wright, M. (2014). The origin of spin-offs: a typology of corporate and academic spin-offs. Small Business Economics, 43(2), 245–259.

Fryges, H., Müller, B., & Niefert, M. (2014). Job machine, think tank, or both: what makes corporate spin-offs different? Small Business Economics, 43(2), 369–391.

Gambardella, A., Giuri, P., & Luzzi, A. (2007). The market for patents in Europe. Research Policy, 36(8), 1163–1183.

Gans, J. S., & Stern, S. (2000). Incumbency and R&D incentives: licensing the gale of creative destruction. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 9(4), 485–511.

Gans, J. S., & Stern, S. (2003). The product market and the market for “ideas”: commercialization strategies for technology entrepreneurs. Research Policy, 32(2), 333–350.

Garrett, R. P., Jr., & Covin, J. G. (2015). Internal corporate venture operations independence and performance: a knowledge–based perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(4), 763–790.

Hahn, D., Minola, T. & Eddleston, K. (2019). How do scientists contribute to the performance of innovative startups? An imprinting perspective on open innovation. Journal of Management Studies, 56(5), 895-928. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12418

Heirman, A., & Clarysse, B. (2004). How and why do research-based start-ups differ at founding? A resource-based configurational perspective. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 29(3–4), 247–268.

Jain, S., George, G., & Maltarich, M. (2009). Academics or entrepreneurs? Investigating role identity modification of university scientists involved in commercialization activity. Research Policy, 38(6), 922–935.

Karnani, F. (2013). The university’s unknown knowledge: tacit knowledge, technology transfer and university spin-offs findings from an empirical study based on the theory of knowledge. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 38(3), 235–250.

Knockaert, M., Ucbasaran, D., Wright, M., & Clarysse, B. (2011). The relationship between knowledge transfer, top management team composition, and performance: the case of science–based entrepreneurial firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(4), 777–803.

Lejpras, A. (2014). How innovative are spin-offs at later stages of development? Comparing innovativeness of established research spin-offs and otherwise created firms. Small Business Economics, 43(2), 327–351.

Lejpras, A., & Stephan, A. (2011). Locational conditions, cooperation, and innovativeness: evidence from research and company spin-offs. The Annals of Regional Science, 46(3), 543–575.

Lindholm Dahlstrand, A. (2001). Entrepreneurial origin and spin-off performance: a comparison between corporate and university spin-offs. In P. Moncada, A. Tübke, R. Miège and T. Botella (eds), Corporate and Research-based Spin-offs: Drivers for Knowledge-based Innovation and Entrepreneurship. Institute for Prospective Technological Studies, Technical Report EUR-19903-EN: Seville, Spain.

Lindholm Dahlstrand, Å., Andersson, M., & Carlsson, B. (2018). Entrepreneurial experimentation: a key function in systems of innovation. Small Business Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0072-y.

Link, A. N., & Sarala, R. M. (2019). Advancing conceptualisation of university entrepreneurial ecosystems: the role of knowledge-intensive entrepreneurial firms. International Small Business Journal. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242618821720.

Mueller, P. (2007). Exploiting entrepreneurial opportunities: the impact of entrepreneurship on growth. Small Business Economics, 28(4), 355–362.

Müller, K. (2010). Academic spin-off’s transfer speed—analyzing the time from leaving university to venture. Research Policy, 39(2), 189–199.

Narayanan, V. (2001). Managing technology and innovation for competitive advantage. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Nelson, R. R., & Winter, S. G. (1982). An evolutionary theory of economic change. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Plummer, L. A., Haynie, J. M., & Godesiabois, J. (2007). An essay on the origins of entrepreneurial opportunity. Small Business Economics, 28(4), 363–379.

Qian, H., & Acs, Z. J. (2013). An absorptive capacity theory of knowledge spillover entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 40(2), 185–197.

Simsek, Z., Fox, B. C., & Heavey, C. (2015). “What’s past is prologue” a framework, review, and future directions for organizational research on imprinting. Journal of Management, 41(1), 288–317.

Visintin, F., & Pittino, D. (2014). Founding team composition and early performance of university-based spin-off companies. Technovation, 34(1), 31–43.

Wennberg, K., Wiklund, J., & Wright, M. (2011). The effectiveness of university knowledge spillovers: performance differences between university spinoffs and corporate spinoffs. Research Policy, 40(8), 1128–1143.

Wiklund, J., & Shepherd, D. (2003). Knowledge-based resources, entrepreneurial orientation, and the performance of small and medium-sized businesses. Strategic Management Journal, 24(13), 1307–1314.

Wright, M., Hmieleski, K. M., Siegel, D. S., & Ensley, M. D. (2007). The role of human capital in technological entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(6), 791–806.

Zahra, S. A., & Wright, M. (2011). Entrepreneurship’s next act. Academy of Management Perspectives, 25(4), 67–83.

Zahra, S. A., Van de Velde, E., & Larraneta, B. (2007). Knowledge conversion capability and the performance of corporate and university spin-offs. Industrial and Corporate Change, 16(4), 569–608.

Zhang, J. (2009). The performance of university spin-offs: an exploratory analysis using venture capital data. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 34(3), 255–285.

Zucchella, A., Palamara, G., & Denicolai, S. (2007). The drivers of the early internationalization of the firm. Journal of World Business, 42(3), 268–280.

Zucker, L. G., Darby, M. R., & Armstrong, J. (1998). Geographically localized knowledge: spillovers or markets? Economic Inquiry, 36(1), 65–86.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Anita van Gils and Dr. Mara Brumana for their contribution to the design of the survey and to Raimondo Carletto for his contribution in exploring the dataset. We want to thank the insightful comments received by the participants to the Academy of Management Perspective Paper Development Workshop (Bergamo, 18 October 2018) and to the 2018 R&D Management Conference (Milan, 2–3 July 2018) where earlier versions of this paper were presented.

Funding

Support for this research was provided by the Italian Ministry of Education under the National Public Research Program (PRIN) through the project “Scientific research and competitiveness. Variety of organizations, support systems, and performance levels”; by the University of Bergamo under the “Excellence Initiative” program “Campus Entrepreneurship”; by UBI Banca; and by Jacobacci & Partners.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Minola, T., Hahn, D. & Cassia, L. The relationship between origin and performance of innovative start-ups: the role of technological knowledge at founding. Small Bus Econ 56, 553–569 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00189-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00189-y