Abstract

Entrepreneurial activity differs substantially across immigrant groups in the USA, but relating self-employment rates in the US to home-country self-employment shares has provided inconclusive results in previous studies. This paper offers new evidence on the relationship between native self-employment and the self-employment decision of immigrants and their descendants. We argue that the previous literature has neglected to account for different proxies of entrepreneurial behavior and for determinants of self-employment in the country of origin. We find mixed evidence of a significant relationship between entrepreneurial activity of US immigrants and two different measures of entrepreneurial activity in their respective countries of origin. Our findings suggest that differences in self-employment across immigrants of different origin are to some degree an expression of the behavior acquired under varying economic and institutional environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Sources: International Labour Office database (average figures, 1969–2000) of the ILO Bureau of Statistics and the World Bank Group Entrepreneurship Survey and Database (2008).

The variable is calculated from the ILO Laborsta database as the share of employers in total active population and relates to averages over the years 1969–2000. Note that the panel from which the average is calculated is unbalanced in the time dimension.

Borjas (1986) finds positive enclave effects for Hispanics in the USA, while Clark and Drinkwater (2000) show that ethnic enclaves decrease the probability to become self-employed in the UK. Further hypotheses are mentioned in the literature, including the sectoral choice model (Fairlie and Meyer 1996) or the tax avoidance hypothesis (Yuengert 1995).

Such an approach has been used, among others, by Carroll et al. (1994), Hendricks (2002), and Osili and Paulson (2008). Hendricks (2002) estimates differences in human capital endowments by measuring differences in labor earnings across US immigrants with identical skills using 1990 US Census data; Carroll et al. (1994) study cultural differences in savings patterns using immigrant data for Canada and the USA; and Osili and Paulson (2008) examine the effect of home-country institutions on the financial behavior of immigrants in the USA. The same data set is used by Michelacci and Silva (2007) to analyze how local entrepreneurship contributes to business creation, see also Yuengert (1995), Fairlie and Meyer (1996), Fairlie and Woodruff (2010).

For ease of calculation, it is restricted to include 100,000 randomly selected US native citizens in the regressions displayed in Table 7 in the Appendix of this paper. The remaining number of observations is 1,324,102. This plays no role with respect to the estimates reported in Sect. 5 (no US natives included).

A few other variables mentioned in the literature that may determine the individual probability of becoming self-employed such as inherited assets and access to funding are not available in the Ruggles et al. (2008) data set and are thus not accounted for.

We do so because some of these individuals—the majority of which are immigrants—also report to be self-employed. This suggests that these observations most likely exhibit a quality bias. We further omit 220 thousand observations that did not indicate the employment status (e.g., employed, self-employed) as well as 4800 unpaid family workers.

We constructed the industry dummies by aggregating dummy variables for those professions that yielded the largest fraction of self-employed persons. The dummies indicate whether a person works in one of the following occupations: agriculture, building and construction, retail, services, transport, and medical. Finally, we also include a dummy variable for household work. Together, these observations cover about half of the sample.

The continental regions are classified as follows. East Asia and Pacific (EAP); Eastern Europe and Central Asia (EECA); Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC); Middle East and North Africa (MENA); North America (NAM); Oceania (OCEA); South Asia (SAS); Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA); and Western Europe (WEU). The results were robust to the inclusion of dummies for dwelling ownership, log investment income, total personal income, state and metropolitan dummies.

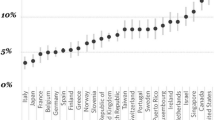

Column (1) of Table 7 reports marginal effects of the dummies for country of origin on the probability of being self-employed overall, and on the probability of being incorporated self-employed in column (2). Columns (3) and (4) report the marginal effects excluding US natives. One may argue that there may be variation in entrepreneurial behavior within countries. This may be true for some countries such as the USA—where we account for possible differences by including state dummies in our regressions—or Switzerland. However, we believe that in the majority of countries, the institutional and economic factors that are likely to shape an entrepreneurial culture (e.g., taxes, contract enforcement regulations, etc.) are specific to countries rather than to within-country regions.

Note that there may be risk of type-1 error with respect to the estimates reported in Fig. 3 and Table 7. In addition, the coefficients will likely be biased so that quantitative interpretations should be handled with care. Nevertheless, they allow us to benchmark our estimates to the previous literature with respect to the direction and an approximate interpretation of the estimates and provide evidence for an overall variation in occupation choices according to different countries of origin of immigrants.

Recall from Sect. 2 that the latter variable refers to employers excluding micro-entrepreneurs and may better fit the incorporated self-employment outcome of the Census sample. We include both of them separately in our baseline regressions in order to test the different influences.

We have obtained data about active businesses between 2001 and 2013 in a variety of countries from the GEM database. These data proved qualitatively similar to ILO self-employment shares; hence, they may represent different economic activities compared to the ones in the USA. Results from regressions using these data proved qualitatively similar to the ones using ILO self-employment shares. Note that there has also been increased interest in latent entrepreneurship, or entrepreneurial intentions, across countries (e.g., Blanchflower et al. 2001; Henrekson and Sanandaji 2014; Fitzsimmons and Douglas 2011, GEM database).

In the data at hand, there are large differences with respect to the time dimension in which these variables have been reported. This implicates that averages refer to rather recent time periods for some and to longer periods for other countries. To address this, we alternatively matched ten-year averages to the time an immigrant has passed in the USA. The results were robust to this procedure.

Other possible and available determinants, including age dependency ratios, literacy, or shares of urban population, are highly correlated with GDP per capita. For this reason, we do not include them in the regressions. Finally, we do not account for income inequality—relative returns to skill may provide another potential determinant of entrepreneurial activity, though not necessarily so if the returns to entrepreneurship are lower compared to paid employment (see also Hamilton 2000; Hyytinen et al. 2013)—as no consistent data covering the period and countries included in our data set are available.

The strong correlations in Fig. 2 confirm the assumption that coverage and quality are sufficient. However, disadvantages of the data at hand are that some important countries such as China, Russia, India, and Cuba are unfortunately missing entirely, and the data include a few suspicious observations. For instance, the reported agricultural employment shares of Argentina and Peru are low. In addition, the unemployment rates of countries such as Bangladesh, Cambodia, Cameroon, Mexico, or Vietnam are very low. This could be due to either low data quality or—and we consider this explanation more likely—to the fact that (because of the absence of social security benefits) job-seeking individuals do not report unemployment or are pushed into self-employment. We also drop Eritrea from the sample regarding the employer share. This country reports one of the highest employer shares, which may be due to measurement error.

Individuals may indicate several—ranked—ancestor countries. This has the advantage that one principal ancestry is given. The disadvantage is that it does not clearly allow us to distinguish between generations in the USA. We therefore have to bear in mind that this potentially produces a bias against finding significant results. Note further that this results in a larger number of observations but not of country groups.

Note that the figures are based on country censuses that may refer to earlier years. The 1949/50 Yearbook contains only overall self-employment. To our knowledge, these figures are the earliest figures available after World War II. Since major immigration occurred after the war, we consider this period an appropriate starting point to our analysis.

These are the earliest years available in the data set at hand. While one could think of sources including earlier figures for GDP, we consider the period at hand to be consistent with the data on self-employment in terms of the time dimension.

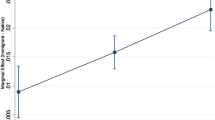

A common assertion states that immigrants arrive with a set of cultural values and behaviors different from those in the destination country and are prone to shocks due to language, new institutions, etc. Although it has been shown that transplanted behavior is persistent, it is possible that institutional factors and cultural norms in the country of immigration become more important. As a consequence, home-country effects may fade over time. Although we are not able to identify assimilation effects using the cross-sectional data at hand, we may obtain a tentative idea by examining the evolution of entrepreneurial activity of immigrants over time using interaction terms for the self-employment share with the discrete duration of residence in the USA. Appendix Fig. 5 shows the marginal effect of home-country self-employment shares evaluated at different intervals of years an immigrant has passed in the USA (i.e., the effect of a change in home-country self-employment shares by 1 percentage points with years in the US held constant at different values). The results are qualitatively similar to the ones in Sect. 5.1, with marginal effects that are increasing in the duration of stay in the USA.

References

Acs, Z., Desai, S., & Klapper, L. (2008). What does “entrepreneurship” data really show? Small Business Economics, 31(3), 265–281. doi:10.1007/s11187-008-9137-7.

Acs, Z., Audretsch, D., Braunerhjelm, P., & Carlsson, B. (2012). Growth and entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 39(2), 289–300. doi:10.1007/s11187-010-9307-2.

Acs, Z. J., & Virgill, N. (2010). Entrepreneurship in developing countries. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 6(1), 1–68. doi:10.1561/0300000031.

Akee, R. K. Q., Jaeger, D. A., & Tatsiramos, K. (2013). The persistence of self-employment across borders: New evidence on legal immigrants to the united states. Economics Bulletin, 33(1), 126–137.

Aldrich, H. E., & Waldinger, R. (1990). Ethnicity and entrepreneurship. Annual Review of Sociology, 16, 111–135. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.16.080190.000551.

Alesina, A., & Giuliano, P. (2010). The power of the family. Journal of Economic Growth, 15(2), 93–125. doi:10.1007/s10887-010-9052-z.

Alesina, A., & Giuliano, P. (2011). Family ties and political participation. Journal of the European Economic Association, 9(5), 817–839. doi:10.1111/j.1542-4774.2011.01024.x.

Alesina, A., Giuliano, P., & Nunn, N. (2011). Fertility and the plough. American Economic Review, 101(3), 499–503. doi:10.1257/aer.101.3.499.

Ardagna, S., & Lusardi, A. (2010). Explaining international differences in entrepreneurship: The role of individual characteristics and regulatory constraints. In J. Lerner & A. Schoar (Eds.), International differences in entrepreneurship (pp. 17–62). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226473109.003.0002.

Armington, C., & Acs, Z. J. (2002). The determinants of regional variation in new firm formation. Regional Studies, 36(1), 33–45. doi:10.1080/00343400120099843.

Audretsch, D. B., Keilbach, M. C., & Lehmann, E. E. (2006). Entrepreneurship and economic growth. New York: Oxford University Press Inc. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.2008.00473_4.x.

Autio, E. (2007). Global entrepreneurship monitor: 2007 global report on high-growth entrepreneurship, Babson College and London Business School.

Bergmann, H., & Sternberg, R. (2007). The changing face of entrepreneurship in germany. Small Business Economics, 28(2–3), 205–221. doi:10.1007/s11187-006-9016-z.

Bisin, A., & Verdier, T. (2010). The economics of cultural transmission and socialization. NBER Working Papers 16512, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. doi: 10.3386/w16512.

Bjørnskov, C., & Foss, N. (2008). Economic freedom and entrepreneurial activity: Some cross-country evidence. Public Choice, 134(3), 307–328. doi:10.1007/s11127-007-9229-y.

Blanchflower, D. G. (2000). Self-employment in OECD countries. Labour Economics, 7(5), 471–505. doi:10.1016/S0927-5371(00)00011-7.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (1998). What makes an entrepreneur? Journal of Labor Economics, 16(1), 26–60. doi:10.1086/209881.

Blanchflower, D. G., Oswald, A. J., & Stutzer, A. (2001). Latent entrepreneurship across nations. European Economic Review, 45(4–6), 680–691. doi:10.1016/S0014-2921(01)00137-4.

Borjas, G. J. (1985). Assimilation, changes in cohort quality, and the earnings of immigrants. Journal of Labor Economics, 3(4), 463–489. doi:10.1086/298065.

Borjas, G. J. (1986). The self-employment experience of immigrants. The Journal of Human Resources, 21(4), 485–506. doi:10.2307/145764.

Bruhn, M. (2011). License to sell: The effect of business registration reform on entrepreneurial activity in Mexico. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(1), 382–386. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00059.

Carroll, C. D., Rhee, B. K., & Rhee, C. (1994). Are there cultural effects on saving? some cross-sectional evidence. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109(3), 685–699. doi:10.2307/2118418.

Clark, K., & Drinkwater, S. (2000). Pushed out or pulled in? self-employment among ethnic minorities in England and wales. Labour Economics, 7(5), 603–628. doi:10.1016/S0927-5371(00)00015-4.

Constant, A., & Zimmermann, K. F. (2006). Legal status at entry, economic performance and self-employment proclivity: A bi-national study of immigrants. CEPR Discussion Papers 5696, C.E.P.R. Discussion Papers.

Djankov, S. (2009). The regulation of entry. World Bank Research Observer, 24(2), 183–203. doi:10.1093/wbro/lkp005.

Djankov, S., La Porta, R., Lopez-De-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2002). The regulation of entry. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(1), 1–37. doi:10.1162/003355302753399436.

Djankov, S., Miguel, E., Qian, Y., Roland, G., & Zhuravskaya, E. (2005). Who are Russia’s entrepreneurs? Journal of the European Economic Association, 3(2–3), 587–597. doi:10.1162/jeea.2005.3.2-3.587.

Djankov, S., Qian, Y., Roland, G., & Zhuravskaya, E. (2006). Who are china’s entrepreneurs? American Economic Review, 96(2), 348–352. doi:10.1257/000282806777212387.

Dreher, A., & Gassebner, M. (2013). Greasing the wheels of entrepreneurship? the impact of regulations and corruption on firm entry. Public Choice, 155(3–4), 413–432. doi:10.1007/s11127-011-9871-2.

Evans, D. S., & Jovanovic, B. (1989). An estimated model of entrepreneurial choice under liquidity constraints. Journal of Political Economy, 97(4), 808–827. doi:10.1086/261629.

Evans, D. S., & Leighton, L. S. (1989). Some empirical aspects of entrepreneurship. The American Economic Review, 79(3), 519–535.

Fairlie, R., & Woodruff, C. M. (2010). Mexican-american entrepreneurship. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 10(1), 1–44. doi:10.2139/ssrn.907681.

Fairlie, R. W., & Meyer, B. D. (1996). Ethnic and racial self-employment differences and possible explanations. The Journal of Human Resources, 31(4), 757–793. doi:10.2307/146146.

Fairlie, R. W., Zissimopoulos, J., & Krashinsky, H. (2010). The international asian business success story? a comparison of chinese, indian and other asian businesses in the united states, canada and united kingdom. In J. Lerner & A. Schoar (Eds.), International differences in entrepreneurship (pp. 179–208). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226473109.003.0007.

Fernández, R. (2008). Culture and economics. In S. N. Durlauf & L. E. Blume (Eds.), The new Palgrave dictionary of economics. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9780230226203.0346.

Fernández, R., & Fogli, A. (2006). Fertility: The role of culture and family experience. Journal of the European Economic Association, 4(2–3), 552–561. doi:10.1162/jeea.2006.4.2-3.552.

Fernández, R., & Fogli, A. (2009). Culture: An empirical investigation of beliefs, work, and fertility. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 1(1), 146–177. doi:10.1257/mac.1.1.146.

Fernández-Serrano, J., & Romero, I. (2014). About the interactive influence of culture and regulatory barriers on entrepreneurial activity. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 10(4), 781–802. doi:10.1007/s11365-014-0296-5.

Fitzsimmons, J. R., & Douglas, E. J. (2011). Interaction between feasibility and desirability in the formation of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(4), 431–440. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2010.01.001.

Giuliano, P. (2007). Living arrangements in western Europe: Does cultural origin matter? Journal of the European Economic Association, 5(5), 927–952. doi:10.1162/JEEA.2007.5.5.927.

Glaeser, E. L. (2007). Entrepreneurship and the city. NBER Working Papers 13551, National Bureau of Economic Research Inc.

Greif, A. (1989). Reputation and coalitions in medieval trade: Evidence on the Maghribi traders. Journal of Economic History, 49(4), 857–882. doi:10.1017/S0022050700009475.

Greif, A. (1993). Contract enforceability and economic institutions in early trade: The maghribi traders’ coalition. American Economic Review, 83(3), 525–548.

Greif, A. (1994). Cultural beliefs and the organization of society: A historical and theoretical reflection on collectivist and individualist societies. Journal of Political Economy, 102(5), 912–950. doi:10.1086/261959.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2003). People’s opium? religion and economic attitudes. Journal of Monetary Economics, 50(1), 225–282. doi:10.1016/S0304-3932(02)00202-7.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2004). The role of social capital in financial development. The American Economic Review, 94(3), 526–556. doi:10.1257/0002828041464498.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2006). Does culture affect economic outcomes? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(2), 23–48. doi:10.1257/jep.20.2.23.

Hamilton, B. H. (2000). Does Entrepreneurship Pay? an empirical analysis of the returns to self-employment. Journal of Political Economy, 108(3), 604–631. doi:10.1086/262131.

Hendricks, L. (2002). How important is human capital for development? evidence from immigrant earnings. American Economic Review, 92(1), 198–219. doi:10.1257/000282802760015676.

Henrekson, M., & Sanandaji, T. (2014). Small business activity does not measure entrepreneurship. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(5), 1760–1765. doi:10.1073/pnas.1307204111.

Hyytinen, A., Ilmakunnas, P., & Toivanen, O. (2013). The return-to-entrepreneurship puzzle. Labour Economics, 20(C), 57–67.

Iyer, R., & Schoar, A. (2010). Are there cultural determinants of entrepreneurship? In J. Lerner & A. Schoar (Eds.), International differences in entrepreneurship (pp. 209–240). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226473109.003.0008.

Kaplan, D. S., Piedra, E., & Seira, E. (2011). Entry regulation and business start-ups: Evidence from Mexico. Journal of Public Economics, 95(11), 1501–1515. doi:10.2139/ssrn.978863.

Klapper, L., Laeven, L., & Rajan, R. (2006). Entry regulation as a barrier to entrepreneurship. Journal of Financial Economics, 82(3), 591–629. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2005.09.006.

Klapper, L., Amit, R., & Guillén, M. (2010). Entrepreneurship and firm formation across countries. In J. Lerner & A. Schoar (Eds.), International differences in entrepreneurship (pp. 129–158). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226473109.003.0005.

Landes, D. S. (1999). The wealth and poverty of nations: Why some are so rich and some so poor. New York: W.W. Norton. doi:10.2307/2658019.

Levie, J., Autio, E., Acs, Z., & Hart, M. (2014). Global entrepreneurship and institutions: An introduction. Small Business Economics, 42(3), 437–444. doi:10.1007/s11187-013-9516-6.

Liñán, F., & Fernandez-Serrano, J. (2014). National culture, entrepreneurship and economic development: Different patterns across the European Union. Small Business Economics, 42(4), 685–701. doi:10.1007/s11187-013-9520-x.

Lofstrom, M. (2002). Labor market assimilation and the self-employment decision of immigrant entrepreneurs. Journal of Population Economics, 15(1), 83–114. doi:10.1007/PL00003841.

Michelacci, C., & Silva, O. (2007). Why so many local entrepreneurs? The Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(4), 615–633. doi:10.1162/rest.89.4.615.

Mueller, P. (2006). Entrepreneurship in the region: Breeding ground for nascent entrepreneurs? Small Business Economics, 27(1), 41–58. doi:10.1007/s11187-006-6951-7.

Ohlsson, H., Broomé, P., & Bevelander, P. (2012). Self-employment of immigrants and natives in Sweden a multilevel analysis. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development: An International Journal, 24(5–6), 405–423. doi:10.1080/08985626.2011.598570.

Osili, U. O., & Paulson, A. L. (2008). Institutions and financial development: Evidence from international migrants in the united states. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 90(3), 498–517. doi:10.1162/rest.90.3.498.

Oyelere, R. U., & Belton, W. (2008). The role of information and institutions in understanding the black-white gap in self-employment. IZA Discussion Papers 3761, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), doi:10.1111/j.0042-7092.2007.00700.x.

Oyelere, R. U., & Belton, W. (2012). Coming to America: Does having a developed home country matter for self-employment in the united states? American Economic Review, 102(3), 538–542. doi:10.1257/aer.102.3.538.

Putnam, R. D., Leonardi, R., & Nanetti, R. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. doi:10.1002/ncr.4100820215.

Rees, H., & Shah, A. (1986). An empirical analysis of self-employment in the UK. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 1(1), 95–108. doi:10.1002/jae.3950010107.

Reynolds, P., Storey, D. J., & Westhead, P. (1994). Special issue: Regional variations in new firm formation. Regional Studies, 28(4), 343–456. doi:10.1080/00343409412331348386.

Reynolds, P. D., Hay, M., & Camp, S. M. (1999). Gem 1999 global report. Tech. rep., Global Entrepreneurship Monitor.

Roland, G. (2004). Understanding institutional change: Fast-moving and slow-moving institutions. Studies in Comparative International Development (SCID), 38(4), 109–131. doi:10.1007/bf02686330.

Ruggles, S., Sobek, M., Alexander, T., Fitch, C. A., Goeken, R., Hall, P. K., King, M., & Ronnander, C. (2008). Integrated public use microdata series: Version 4.0 [machine-readable database]. Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota Population Center [producer and distributor].

Stuetzer, M., Obschonka, M., Brixy, U., Sternberg, R., & Cantner, U. (2014). Regional characteristics, opportunity perception and entrepreneurial activities. Small Business Economics, 42(2), 221–244. doi:10.1007/s11187-013-9488-6.

Tabellini, G. (2010). Culture and institutions: Economic development in the regions of Europe. Journal of the European Economic Association, 8(4), 677–716. doi:10.1111/j.1542-4774.2010.tb00537.x.

Tubergen, Fv. (2005). Self-employment of immigrants: A cross-national study of 17 western societies. Social Forces, 84(2), 709–732. doi:10.1353/sof.2006.0039.

van Hoorn, A., & Maseland, R. (2010). Cultural differences between east and west germany after 1991: Communist values versus economic performance? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 76(3), 791–804. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2010.10.003.

Wyrwich, M. (2015). Entrepreneurship and the intergenerational transmission of values. Small Business Economics, 45(1), 191–213. doi:10.1007/s11187-015-9649-x.

Yuengert, A. M. (1995). Testing hypotheses of immigrant self-employment. The Journal of Human Resources, 30(1), 194–204. doi:10.2307/146196.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Silvia Ardagna for a fruitful discussion at the World Bank Conference on Entrepreneurship and Growth. We are grateful to Matthias Bannert for providing generous advice regarding computational issues. We also received helpful comments from Sule Akkoyunlu, Peter Egger, Richard Jong-A-Ping, Leora Klapper, Sarah Lein, Nora Strecker, seminar participants at the World Bank Conference on Entrepreneurship and Growth, the Beyond Basic Questions Seminar in Zurich, the KOF Brown Bag Seminar, and the Spring Meeting of Young Economists in Istanbul, and two anonymous reviewers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Fig. 5; Tables 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9.

Home-country self-employment share and years passed in the USA. Notes: Marginal effects and 95 % confidence intervals from logit regressions with clustered standard errors evaluated at different years an immigrant has spent in the USA, other variables at sample means. The dependent variable is a dummy for being (incorporated) self-employed (immigrants only). The estimations include the following variables not reported above: age, age squared, gender, number of children, dummies for marital status, education, proficiency in English, industry of employment, and state dummies (Ruggles et al. 2008). Self-employment and employer share in total active population: ILO Laborsta, average 1969–2000

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lassmann, A., Busch, C. Revisiting native and immigrant entrepreneurial activity. Small Bus Econ 45, 841–873 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-015-9665-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-015-9665-x